The castles of Teck and Urach are not instantly familiar to even the most seasoned travellers, but both lent their names to dynasties with interesting close connections to more well-known royal and princely families—notably the Windsors and the Grimaldis—and even to an ephemeral kingdom in the Baltic that vanished before the ink was dry on the page. Both families, Teck and Urach, are branches of the ancient royal house of Württemberg, in southwest Germany. English readers will certainly know the name ‘Mary of Teck’, the grandmother of Elizabeth II, portrayed with great eloquence and style in The Crown by Eileen Atkins. Not many know the story of her family, however, or the origins of the name Teck.

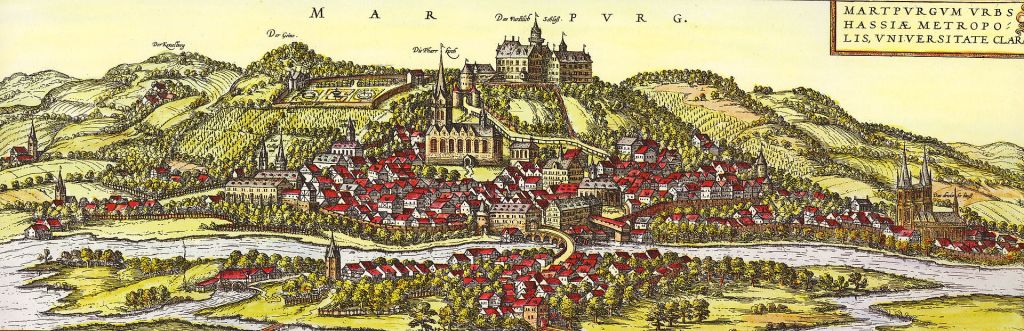

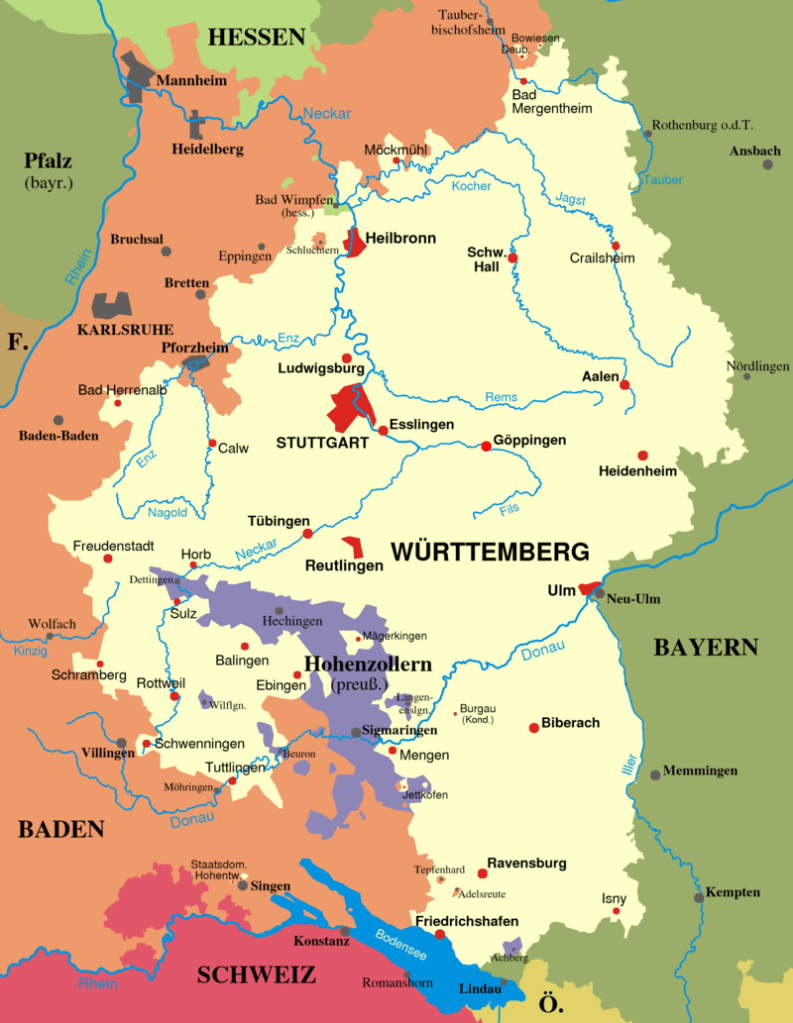

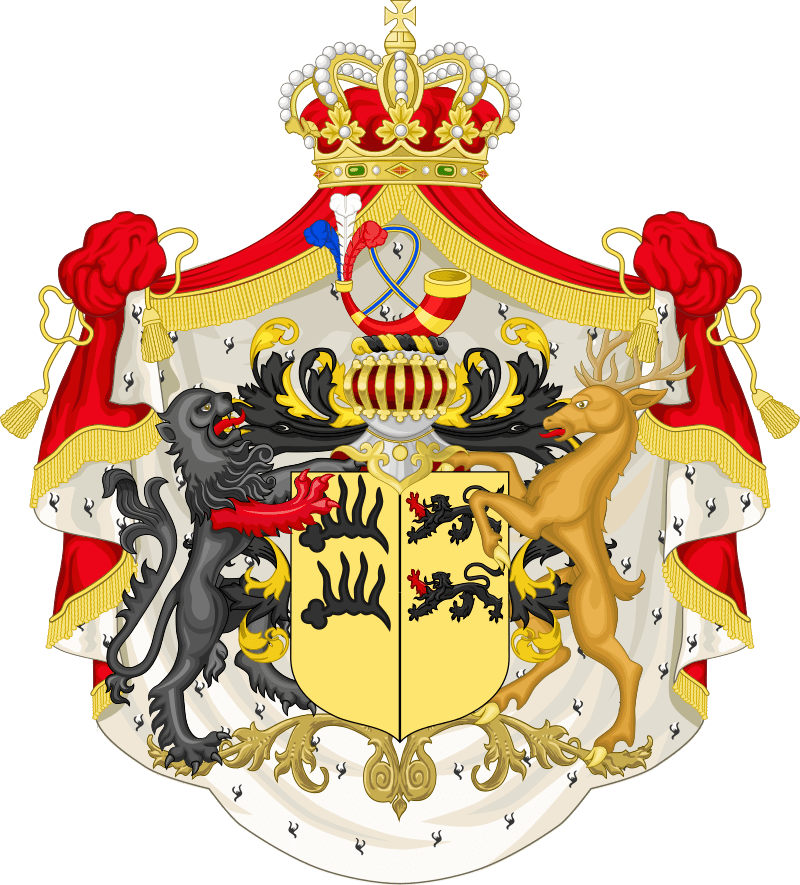

The House of Württemberg, dukes from 1495, and kings from 1806, trace their lineage back to feudal lords who dominated certain hilltops and river valleys east of Stuttgart. They carved out their own county in the 12th and 13th centuries as the ancient Duchy of Swabia disintegrated. The Dukes of Württemberg will have a separate blog post of their own; here we can focus on two castles on the eastern edges of their realm, Teck and Urach. Both were built in the on spurs of the northern edge of the ‘Swabian Jura’, the low mountain range that separates the watersheds of the Danube (south) and Neckar (north) rivers.

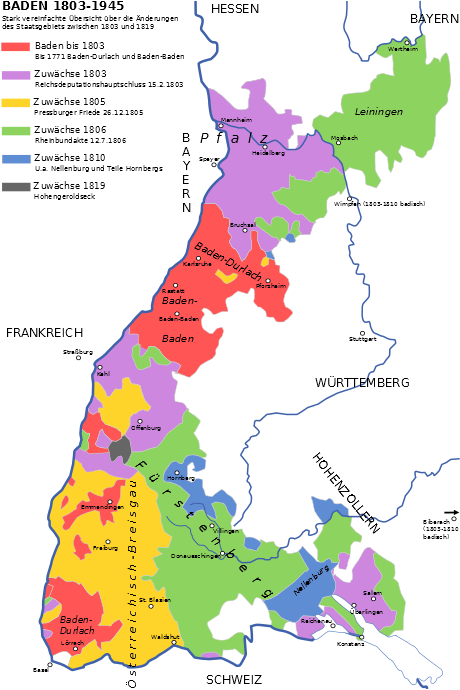

Both castles were also originally held by the much more powerful regional dynasty, the Zähringer, created dukes in 1098 (and ultimately progenitors of the House of Baden—so again, subjects of another separate post). From 1187, a younger brother of Duke Berthold IV, Adalbert, was given the castle of Teck and founded his own branch of the family. They used the title ‘duke’, but in these early days, this really was more attached to the person or the dynasty, not to a particular castle or territory. Adalbert’s nephew, Duke Berthold V, died in 1218, bringing the senior line to an end, and his sister and co-heiress, Agnes, married a local count, Egon von Urach, and brought with her in marriage a sizeable portion of the Zähringer lands in the southwestern corner of modern Germany.

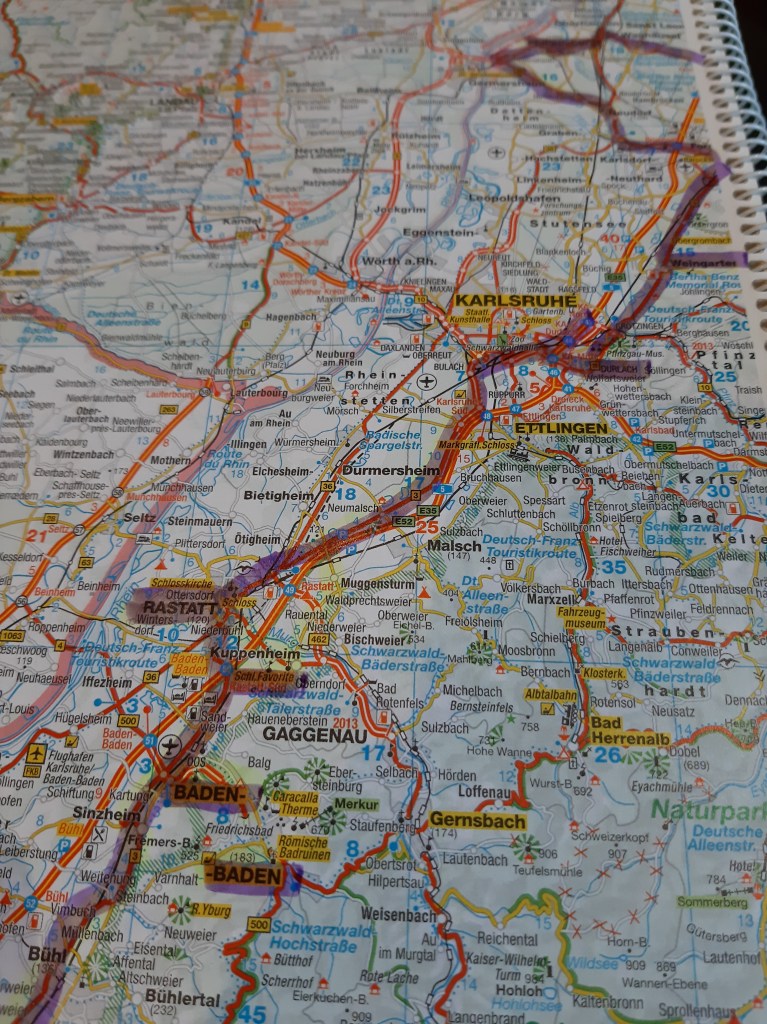

So by the 1220s, the dukes of Teck and the counts of Urach dominated the region to the south and east of the town of Stuttgart, where the counts of Württemberg were beginning to build their domain. By 1260, the latter had acquired the castle and lands of Urach, and it would serve as the capital of one of the branches of the family when it divided in the 15th century. The counts of Württemberg-Urach built a renaissance palace as a residence in the town of Urach (which remains today) and allowed the castle up on the hilltop to degrade. It was a prison by the 17th century, and was dismantled by the dukes of Württemberg in the 18th century, to use the stones in other building projects.

The dukes of Teck lasted longer as a separate dynasty, and had some influential members: Conrad II was a potential candidate for the election to the Imperial throne in 1291, but was reputedly murdered by the rival faction before he could claim his title. Ludwig, the last duke, was also Patriarch of Aquileia, an ecclesiastical territory in the far northeast corner of Italy, until he was run out by the armies of Venice in 1420. As a senior churchman, he had been prominent in his opposition to some of the attempts at reconciling the Great Schism. With his death in 1439, the dynasty of Zähringen-Teck became extinct—but the castle itself had already been sold to the counts of Württemberg, in 1381. The castle was heavily damaged in the Peasants War of 1525 and never really recovered. There were plans to rebuild it in the 1730s, but these came to nothing. In the 19th century, a tower was built on the ruins, and in the 20th century the site was redeveloped for a hiking lodge and nature reserve.

So by the late 18th century, both castles were ruins held by the dukes of Württemberg (who also always used the title ‘duke of Teck’ and sometimes ‘duke of Urach’). Duke Friedrich II became an ally of Napoleon and was rewarded by a significant augmentation of his lands (through annexation of smaller secular and ecclesiastical territories), and an even more significant augmentation of his title, becoming the first King of Württemberg in 1806 as part of the demise of the Holy Roman Empire. King Friedrich’s brother Wilhelm and nephew Alexander would be the founders of the modern families of Urach and Teck, respectively, and will be the focus of the rest of this post. Both of these families were started due to ‘morganatic’ marriages—a term used by German princely families to indicate that, while it was a legal and sacramentally valid marriage, the bride and groom were of unequal rank and therefore their children could not inherit their father’s rank or titles (and in this case, his claims to a royal succession). This is different from another kind of descent, illegitimate, which ties our story here, very loosely, to another descendant of King Friedrich I, Boris Johnson, the British Prime Minister, whose ancestry was revealed on the television programme Who Do You Think You Are? in 2008, via an illegitimate grand-daughter, Karoline, who married Baron Charles de Pfeffel, whose great-grand-daughter married Johnson’s grandfather. On the programme, more was made of the descent back another generation or two to the British royal family, and that connection will become relevant again when we get to the dukes of Teck, but I’ll start with the dukes of Urach.

Duke Wilhelm of Württemberg was the third of six younger brothers of King Friedrich I. He’s called a ‘duke’ because, in Germanic tradition, all children held the same rank as the head of the family (so the children of a ‘Count von Adelburg’ would all be count or countess of Adelburg). Wilhelm had to earn his own living, so, as was normal, he joined the army. But not the local one—he made his name in the army of the King of Denmark, rising to the rank of lieutenant-general in 1795, and was named governor of Copenhagen in 1801.

In 1806, Wilhelm was asked to return home by his brother, the newly crowned king, to become first Minster of War for the new Kingdom. While in the north he had fallen in love and married a Swedish noblewoman, Baroness Wilhelmine von Tunderfeldt-Rhodis, whose family had connections to Wilhelm’s mother’s family in Brandenburg. The marriage was deemed unequal, so their children were styled ‘count’ or ‘countess’ of Württemberg.

The eldest, Count Alexander, embraced the culture and emotions of the early Romantic era, perhaps as a child of love rather than duty, and he became a well-regarded poet and hosted a circle of famous German writers and poets at his castle. It seems he drank rather too deeply however at this emotional fountain and spent much of his relatively short life (he died at 43) in deep depression. He did marry, and left two sons, Eberhard and Alexander, but these died unmarried and this branch died out by the end of the century.

The second son, Wilhelm, took a much more expected career path, and by the 1850s was a general in the Württemberg army. Like his father, Duke Wilhelm, he was also quite interested in science and technology, and published on quite a wide range of topics (and was awarded an honorary doctorate from the University of Tübingen).

He was also quite interested in history, and, like many aristocrats of his age, was inspired to build a new castle along medieval lines. In the 1840s, he acquired the site of an ancient ruin, Lichtenstein Castle, and rebuilt it from scratch. This became his family’s seat, and they still live there today (not to be confused with Liechtenstein, the sovereign principality).

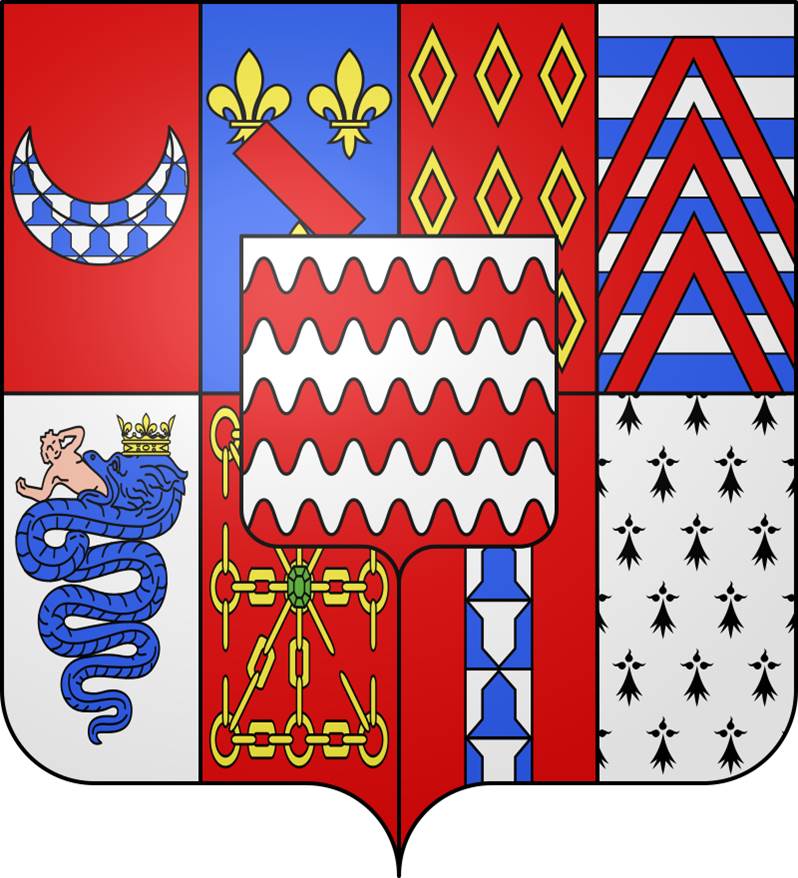

Also in the 1840s, Wilhelm converted to Catholicism in order to marry Princess Théodeline de Beauharnais, whose father, the famous Prince Eugène (Napoleon’s adopted step-son), had taken up residence as an exile from France in the nearby duchy of Leuchtenberg. They had four daughters, but no sons, so after her death he re-married, in 1863, another princess, but of a slightly higher rank, since Monaco was a sovereign principality (even if tiny). Princess Florestine was a ‘serene highness’ so in 1867, the King of Württemberg raised his cousin to the rank of ‘Duke of Urach’—the name taken from the old ruined castle to the north of Lichtenstein—and the style of address ‘serene highness’. It was a dukedom in name only; it didn’t come with any territory.

The first Duke of Urach died only two years later, so his widow spent much of her time back in Monaco, where her two sons, Wilhelm and Karl, were raised quite culturally francophone. Duchess Florestine frequently lent a hand to her brother, Prince Charles III of Monaco, whose health was poor and was nearly blind by the 1880s; and she assumed government responsibilities again in the 1890s when her nephew, Prince Albert I, was frequently absent, travelling on oceanographic expeditions.

Florestine died in 1897, and her son Wilhelm, now the 2nd Duke of Urach, established himself once more in Germany, as a military commander, and as son-in-law of one of the Bavarian royal dukes. His wife, Amalia, was in fact a niece of the Austrian Empress ‘Sisi’, so Wilhelm had access to the highest royal circles. He was not therefore seen as appropriate by the French governing elites to be a potential heir to the Monegasque throne. By 1911, Prince Albert I was aging and unpopular, and his son Louis was still unmarried—a law was swiftly passed naming Louis’ illegitimate daughter Charlotte formally as heir to the principality. The Duke of Urach protested, but had other prospects: in 1913, he was considered for the newly created throne of Albania; in 1917, there was talk of naming him ruler of a new ‘Grand Duchy’ of Alsace-Lorraine; and in June 1918, he was selected by the independence party of Lithuania to be their king. He was an ideal candidate, since he was a Catholic, distantly descended from the ancient grand dukes of Lithuania, and was related to German ruling houses (necessary to defend their new independence against the Russians) but was not a Hohenzollern. Although he did not have time to travel to Lithuania before the entire idea collapsed in November, he did briefly assume the name ‘Mindaugas II’ to commemorate the founder of the first Lithuanian monarchy in the 13th century.

By the 1920s, the 2nd Duke retired quietly to Schloss Lichtenstein, married another Bavarian princess (Wiltrud), and in 1924, formally renounced any claims he might have to the throne of Monaco. He died in 1928, but his widow lived on until 1975, and was probably influential in ensuring that her step-sons were mindful of the Imperial regulations about marriage (even through the Empire no longer existed): that only equal marriages were permitted if claims to sovereignty were to be transmitted from generation to generation.

Duchess Wiltrud’s step-sons did not all agree however. The eldest, another Wilhelm, embraced the 20th century, married for love (a commoner), studied for an engineering degree and became a senior engineer and director at Daimler-Benz in the 1920s-50s. He also spent time as part of the new management of the Renault factories in occupied France. His brother, Karl Gero, who succeeded their father as 3rd Duke of Urach, was more deeply involved in the Nazi regime, rising to the rank of major in the Wehrmacht. He had married someone of equal rank, but they had no children, so when he died in 1981, the question of succession was raised again. The third brother, Albrecht, had married a commoner, and was disqualified (though in 1930s, there were rumours in Paris that he wanted to be re-considered as heir to Monaco, following the scandalous separation, and later divorce, of Princess Charlotte). The claims to the Urach ducal title therefore passed to the sons of the fourth brother, Eberhard, who had married a Thurn und Taxis princess. Karl Anselm thus became the 4th Duke in 1981, but renounced it in 1991, to marry a commoner; his brother Wilhelm took on the title, and in 1992 married a Belgian noblewoman who many thought could be considered equal, but others did not. His younger brother, Inigo, who had married the year before a German noblewoman who was more clearly ‘equal’, therefore contested the claim, and the two brothers decided that Wilhelm would be the 5th Duke of Urach and hold the lands (including Lichtenstein Castle) within Germany, while Inigo would revive the family claims to the Kingdom of Lithuania—and he reportedly started learning the language and visited the country in the early 2000s. Both brothers are now in their sixties, so this arrangement can carry on for some time yet, but it will be interesting how the next generation settles it (if the next generation even cares at all).

The story of the dukes of Teck is a lot more straightforward, but jumps to much greater heights (in royal circles) within only the first generation. They became extinct in the male line in 1981 (and in the female line in 1999).

Stepping back to the first years of the 19th century, the nephew of Württemberg’s first king, Duke Alexander, pursued a military career outside his native land much like Duke Wilhelm, and also like him, married for love outside the circles of the acceptable princely families. Whereas Wilhelm had gone north to Denmark, Alexander went east and in the 1830s became colonel in the army of the Austrian Empire, rising to the rank of general of cavalry by the 1850s.

While Duke Alexander was stationed in Vienna, he met and married a Hungarian countess, Claudine Rhédey von Kis-Rhéde. Her family were not princely, but they were one of the oldest noble houses of Hungary, claiming descent back to the founders of the Hungarian monarchy in the 11th century. Their castle was in the far east of the Kingdom, in Transylvania in what is now Romania. The village today remains 90% Hungarian and a majority Calvinist. Upon their marriage in 1835, Claudine was created Countess of Hohenstein, a title she could pass on to their children (the first being born a year later). Hohenstein was the name of yet another ruined castle in the region of Württemberg southeast of Stuttgart. After giving birth to three children, Countess Claudine was tragically killed falling from her horse while watching a cavalry charge of her husband’s regiment (another story says she died from wounds she suffered, pregnant, in a carriage accident). The three Hohenstein children were left motherless.

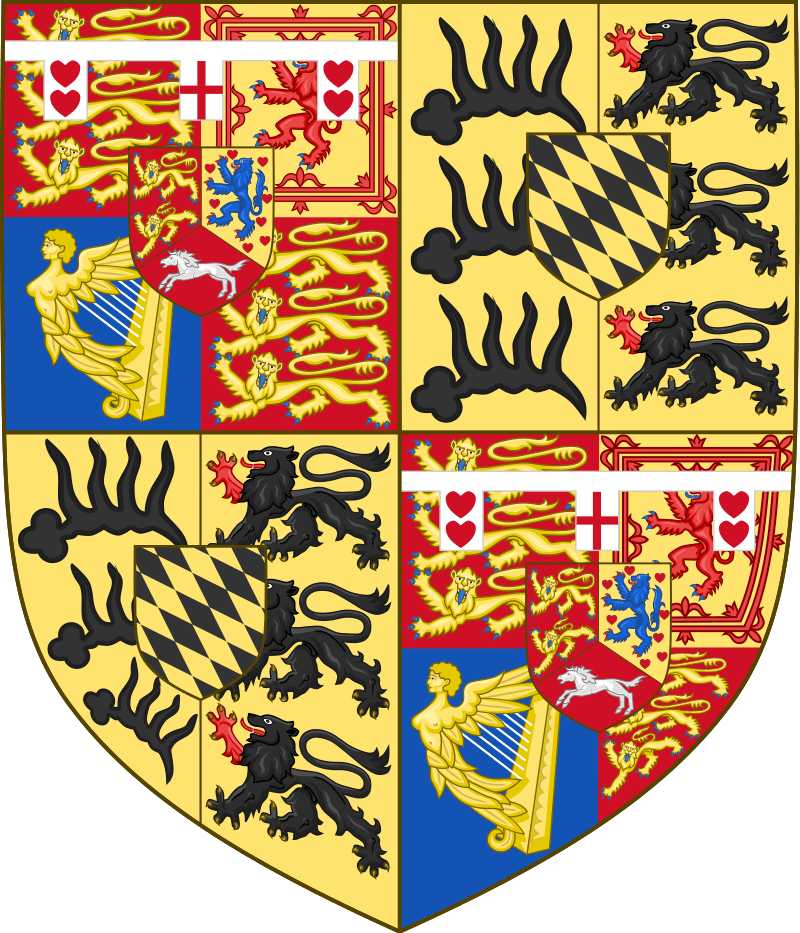

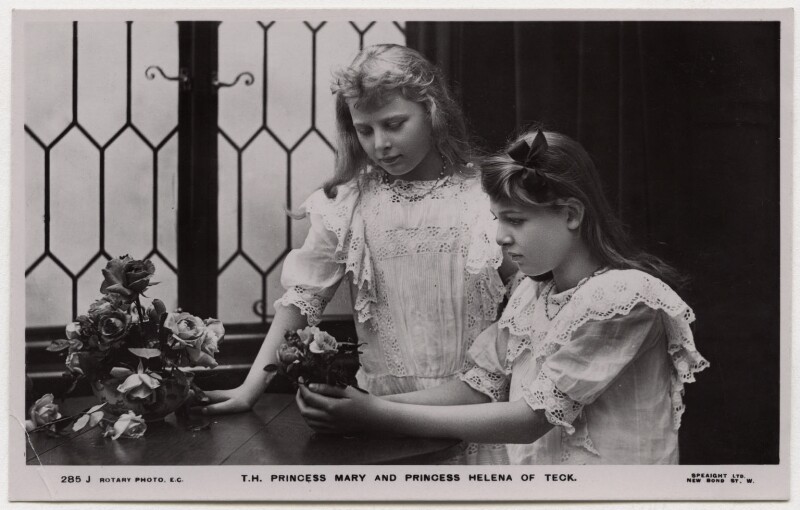

The eldest and youngest were girls, Claudine and Amalia. Amalia married an Austrian count and settled into a quiet life near Graz, while Claudine purchased a house nearby and remained close to her sister. In 1863, both of them, and their brother Franz, were elevated in rank by their cousin the King of Württemberg: they were prince and princesses of Teck, with the style of ‘serene highness’. Like his father, Prince Franz joined the Austrian army, became a captain in the Hussars, and served in Austria’s wars against Sardinia in 1859 and against Denmark in 1864. A year later, in Vienna, Franz met the Prince and Princess of Wales, who invited him to London to meet their cousin, Princess Mary Adelaide of Cambridge. In March they met, in April they were engaged, and in June they were married.

Franz and Mary Adelaide were cousins, both descendants of King George II of Great Britain. But while he was considered one of the handsomest men in the Austrian army, she unfortunately resembled the Hanoverians, full of face and figure. He had princely blood, but she was a full royal princess of Hanover and Great Britain. As long as they stayed in Britain, she received a pension from Parliament, so he resigned his commissions and started a new life as an Englishman.

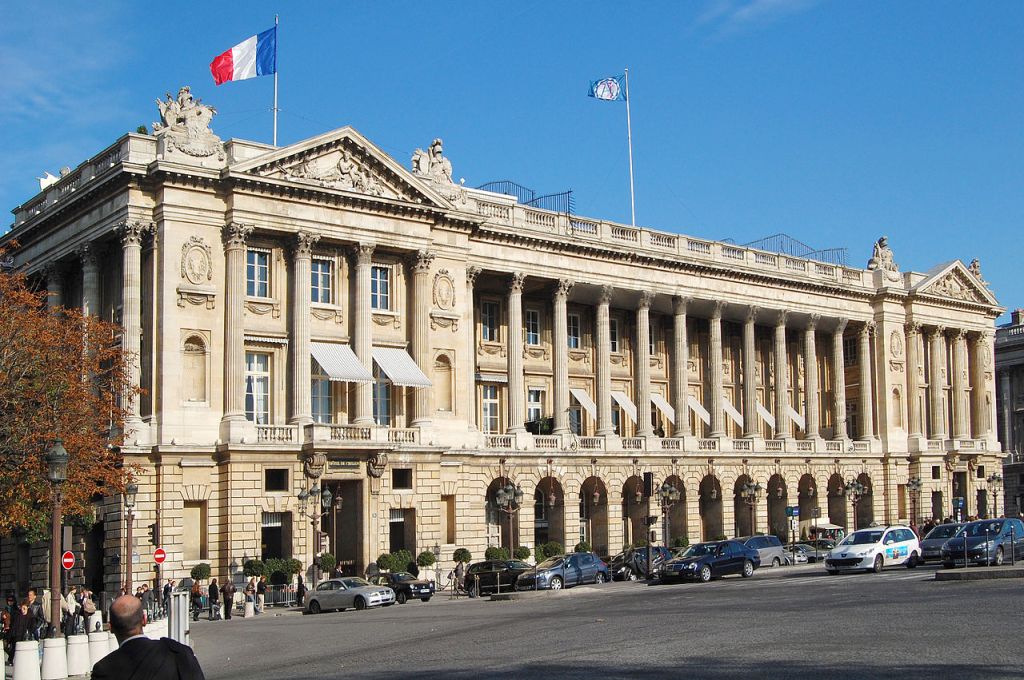

Mary Adelaide herself is usually portrayed as ‘very English’, in contrast to her German husband, but a more careful examination of her life shows that she was nearly as German as he was: her mother was a princess of Hesse-Kassel, and she was born in Hanover, where her father, Adolphus, Duke of Cambridge, was acting as viceroy of the Kingdom of Hanover. Indeed, Adolphus, 7th son of George III, had been sent to school in Hanover by age 12, spent most of his military career here during the Napoleonic wars, then governed the territory in the names of his elder brothers from 1813 to 1837. After Hanover and Britain were separated at the accession of Queen Victoria, Cambridge and his children, including Mary Adelaide, returned to England and settled at Cambridge House on Piccadilly, where he died in 1850.

By 1866, Mary Adelaide was in her thirties and had no real source of income, unlike her brother who had taken over his father’s position in the army (he was commander-in-chief of the army from 1856), or her sister who had married the Grand Duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz. So a marriage to a handsome foreign duke, even a poor one, was seen as advantageous. Queen Victoria made rooms available to them in Kensington Palace and in 1869 gave them the use of White Lodge in Richmond Park, to raise their already growing family: Victoria Mary (known as ‘May’), born in 1867, and Adolphus (‘Dolly’) in 1868. White Lodge was built in the 1730s by George II and housed various royals over the ensuing century. The Tecks lived there until the end of the 19th century, and since 1955 it has been the home of the Royal Ballet School.

In 1871, the Prince and Princess of Teck were raised one more rung in the hierarchy of royal princes by being named Duke and Duchess of Teck. I haven’t been able to find out why this happened. Perhaps it was a way for the King of Württemberg to establish his place within the new German Empire (founded that year), by stressing that his house had two cadet branches, Urach and Teck, that were not mere nobles, but princely (fürstliche) dukes. The new Duchess of Teck already retained her Royal Highness rank, and pressed Queen Victoria to extend this honour to her husband, but Victoria refused; relenting somewhat in 1887 to give him the rank of Highness (not Royal Highness) as part of her Jubilee honours.

Meanwhile, the Duke started to find his own ways to alleviate his family’s cashflow problem. They went abroad for a few years in the early 1880s, to live cheaper in Florence, or to stay with relatives in Germany. Then by the end of the decade he reactivated somewhat his military career: he served with the British army in Egyptian campaigns, and was given ranks in the army of Württemberg (1889) and the Imperial army (1891), then promoted to major-general in the British army, 1893, and lieutenant-general in the Imperial army (1895)—though most of these were honorary or ceremonial positions. He died in 1900, three years after his wife. They were buried in the new royal burial area, Frogmore, in Windsor.

Of the four children of the 1st Duke and Duchess of Teck, the best known is of course the eldest, Princess May, who became Queen Mary, wife of George V and grandmother of Queen Elizabeth II. She was famously born in the same room as Victoria had been in Kensington Palace. In December 1891, she became engaged to Prince Albert Victor (‘Eddie’), the eldest son of the Prince of Wales. He died in mysterious circumstances only six weeks later, and by the Spring of 1893 she was engaged to his brother the Duke of York, and they married in July. The rest of Queen Mary’s story is well known, as Duchess of York, then Queen consort, then Queen dowager, until her death in 1953.

Her brother succeeded as 2nd Duke of Teck in 1900. As a young man, Prince Adolphus had joined the cavalry regiment of his uncle, the Duke of Cambridge, then switched to become Captain of the Life Guards in 1895. The year before, he married Lady Margaret Grosvenor, daughter of the 1st Duke of Westminster, thus securing for himself a place within high society nearly as grand as his sister’s. He served in the Boer War in South Africa in 1899, and in 1911 was honoured by his brother-in-law, the now king George V, with the grant of ‘Highness’ just like his father had been. This was followed by the post, in 1914, of Governor and Constable of Windsor Castle.

Once the war broke out, the Duke acted as a military secretary to the War Office and to the British Commander-in-Chief in France, but retired from active service in 1916 due to illness. A year later, he joined the Windsors in attempting to purge the royal family of its overtly German names and titles, and in July 1917, renounced his title ‘Duke of Teck’ and took instead the name ‘Cambridge’, after his mother’s family. In November, the King created him Marquess of Cambridge, Earl of Eltham and Viscount Northallerton (I’d love to know why these particular lesser titles were chosen for the courtesy titles—did the family have a connection to Eltham Palace before the Courtaulds bought it in the 1930s?). After the war, the 1st Marquess withdrew mostly from public life—and when suggested as a possible candidate for the Hungarian throne in the 1920s, as a descendant of Hungarian nobility, rejected the notion as preposterous—and lived at Shotton Hall, near Shrewsbury in Shropshire. A handsome red brick manor house, it later became a school and is now subdivided into flats. He died in 1927 followed by his wife in 1929.

Their children, all born as prince or princess of Teck, had become lords and ladies of Cambridge in 1917. The eldest, George, became 2nd Marquess of Cambridge in 1927. Like his ancestors, he led a military career, becoming a major in the Service Corps in the Second World War, but was also a banker in the City. He married a grand-daughter of the 13th Earl of Huntingdon. As more ‘fringe’ members of the royal family, he and his wife did appear at most grand functions, but didn’t carry out royal duties. When he died in 1981, the male line of the House of Teck/Cambridge became extinguished.

The Cambridges had only one child, Lady Mary Cambridge, who became Lady Mary Whitley in 1951. She had been a childhood companion of the princesses Elizabeth and Margaret in the 1930s (her parents lived close to the Yorks just off Hyde Park), and was a bridesmaid at Elizabeth’s wedding in 1947. When she died in 1999, it was remarked that the Queen lost one of those closest to her since childhood.

There were three other Cambridge children: Lord Fredrick, killed in Belgium in 1940, and two daughters. The elder, Lady Mary, married the Duke of Beaufort in 1923, and is remembered for having hosting her aunt, Queen Mary, during the evacuation of London in World War II at her country house, Badminton. When I visited Badminton many years ago, I was told the story of how horrified Duchess Mary was to see her aunt arrive with literally hundreds of suitcases and hatboxes, but also to discover the truth about the Dowager Queen’s propensity to ‘shoplift’ valuable objects she took a fancy to when visiting country homes. The second daughter, Lady Helena, married Col. John Gibbs, a veteran of the Boer War and the First World War.

The two younger sons of the 1st Duke of Teck were also veterans of overseas conflicts. Prince Francis (‘Frank’) was a major in the Royal Dragoons, serving in South Africa and Egypt, but dying in 1910 before he could serve in WWI (or indeed change his name and titles). He had been known as a bit of a rake, a gambler and ladies’ man who purportedly gave away some of the family jewels, and possibly left behind an illegitimate child or two. When he died, his will was sealed on the orders of Queen Mary to avoid any potential scandals. Frank’s brother Alexander (‘Alge’) was a bit more upstanding. He also served in South Africa, and in World War I in the Life Guards. When the family exchanged their titles in 1917, he was created Earl of Athlone (in County Westmeath, in the centre of Ireland), and Viscount Trematon (in Cornwall). In 1904, he had married Princess Alice of Albany, a grand-daughter of Queen Victoria, and they occupied her family apartments in Kensington Palace. They also lived at Brantridge Park in West Sussex, a villa from the mid-19th century in the hilly area south of London (not far from Crawley).

As grand-daughter of a sovereign, Princess Alice kept her rank (HRH), which augmented her husband’s position somewhat, so that the Earl of Athlone was more in the public eye than his elder brother or nephew. In 1923 he was named Governor-General of South Africa, where he attempted to navigate the complex political situation there in the 1920s. In 1931, he returned to England and was named Governor and Constable of Windsor Castle (like his brother), and nine years later was sent abroad again, this time to Canada. While Governor-General (1940-46) he and his wife were kept busy receiving and entertaining the numerous exiled royals who went to Canada during the Second World War: Norway, Luxembourg, Netherlands, etc. He died in 1957, but she lived on until 1981, the last of Queen Victoria’s grandchildren.

The Count and Countess of Athlone had three children. Of the two boys, Maurice lived only a month in 1910, and Rupert died age 20 in an automobile accident in France, a victim of his mother’s family’s haemophilia. Their daughter, another May, lived a long life as another distant member of the royal family. Unlike the previous Lady May Cambridge, she was not only a bridesmaid at a royal wedding, but the other way round, with young Princess Elizabeth acting as a bridesmaid in her 1931 wedding to Henry Abel Smith, part of a London banking clan. She died in 1994, bringing her branch of the Teck family to an end.

Württemberg, Urach, Teck, even Monaco and Lithuania: all names that tied together the network of royal and semi-royal families of Europe until the middle of the 20th century.

[images from Wikimedia Commons]