Transylvania. The name conjures up images of vampires and werewolves, and the most famous vampire of all, Count Dracula. But really, his story is part of the Principality of Wallachia and the Carpathian mountains which separate that region from Transylvania. The potential historic inspiration for Dracula, Vlad the Impaler, thus belongs to another blog post, for the princes of Wallachia and Moldavia, and a series of Romanian families. Another favourite tale of horror from this region is of the ‘Blood Countess’, Elizabeth Báthory, whose gruesome murders were said to run into the hundreds. But her chief domains, and the sites of her alleged horrific crimes, lay in what was once known as Upper Hungary, and is now the modern nation of Slovakia.

Báthory’s family, however, did hold much of their lands in the region ‘across the forest’ from the main body of the Hungarian kingdom—ie, ‘trans sylvania’—and they did take on the position of prince of Transylvania for three generations in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. For Transylvania did not have a specific princely dynasty of its own: at times it was simply a province of the Kingdom of Hungary, and at others a breakaway principality, ever-shifting between sovereignty and loyalty to either the Habsburg king or the Ottoman sultan. This blog post is thus about a series of Hungarian magnate families who rose from their status as ordinary nobles to be princes for a generation or two, then faded back from power. This will be a blog about the Zápolya, Báthory, Rákóczi, Bethlen, Apafy and others—amongst the most famous names in all of Hungarian history.

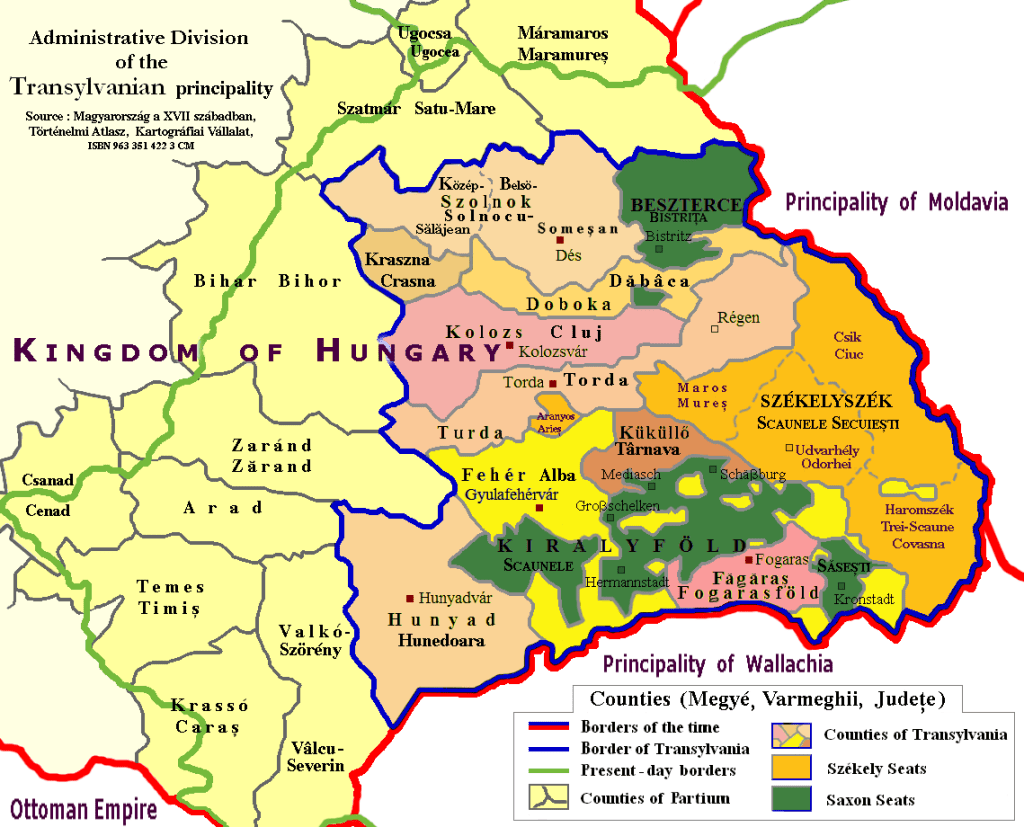

Today, Transylvania is one of the three regions that make up the modern nation of Romania (alongside Wallachia and Moldavia). For a thousand years, however, if was a frontier zone of mixed ethnicities, Romanians, Hungarians, Slavs and Germans. Still today there is a significant portion of its population who refer to themselves as Szeklers (or Székelys) who are ethnically Hungarian, and those called the Saxons (or Sachsen) who descend from German settlers who came to the region in the 12th and 13th centuries. The Magyar tribes first settled in this region in the late 9th century, but there were also some Vlachs here, probable descendants of the Roman colonists of the province of Dacia from the 2nd century AD, and also some Slavs, who may have given the name to the region’s capital, Balgrad, ‘white castle’ which translates as Fehérvár in Hungarian, Weissenburg in German, and Alba Julia in modern Romanian. The latter name, however, adds the name ‘Julius’, which might suggest a Roman connection, but in fact refers to one of the first Hungarian chieftains to establish a principality here for himself, Gyula. So the full name of his capital was Gyulafehérvár: ‘Gyula’s White Castle’ (in the 18th century it was for a time renamed ‘Karlsburg’, for the Emperor Charles VI).

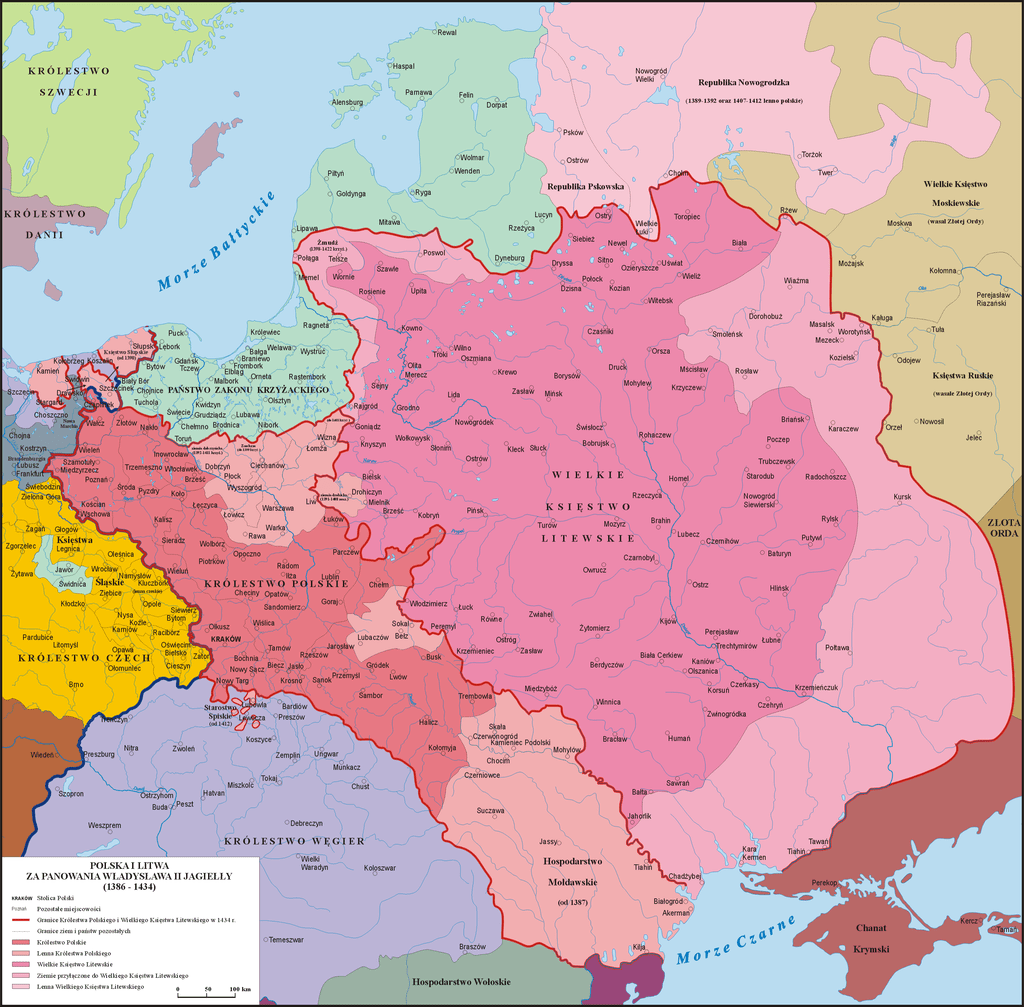

Prince Gyula, one of several pagan Magyar chiefs who arrived in the Pannonian basin—the wide flat plain watered by the Danube and its tributaries—in the 9th century, supposedly defeated a local Vlach (Wallachian or Romanian) duke, Gelou, and set up his rule in this eastern portion of the great basin, while the other Magyar chiefs settled to the west in Hungary proper. There are also suggestions that ‘gyula’ may not be a person, but a military title (seen as ‘gyla’ in Byzantine sources), or perhaps a series of rulers named Gyula. Whatever the truth, according to medieval chronicles, in 1003, the first Christian king of Hungary, St. Stephen, defeated this Prince Gyula, and integrated Transylvania fully into the Kingdom. Gyula may even have been Stephen’s uncle, the father of his queen, Sarolt. Stephen also defeated other dukes, probably Vlachs, in the region: Ajtony (or Ahtum) and Menumorut. From this point onwards, Transylvania did not have its own prince, but a voivode, or governor, appointed by the Hungarian king.

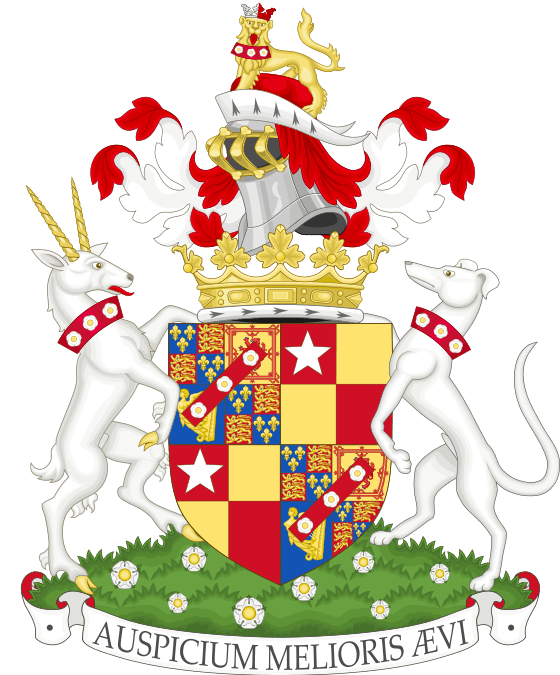

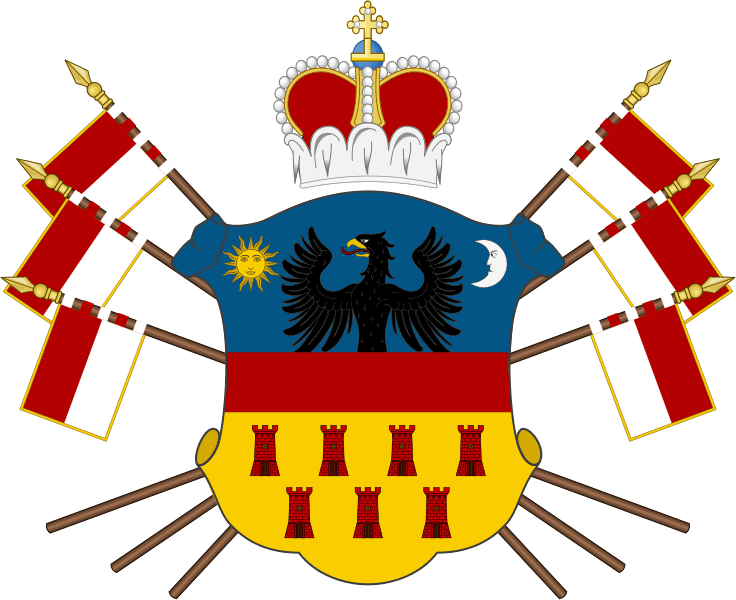

By the 12th century, the region was known in Hungarian as Erdély, which probably derives from Erdő elve, ‘beyond the forest’, or überwald in German. But the Germans also begin to call it Siebenbürgen, ‘seven castles’, for the seven fortified cities established by the Saxons who were brought in by Hungarian kings about this time to fortify the border between Hungary and the Byzantine Empire (and subsequently the Ottoman Empire). These seven castles feature on the coat-of-arms of Transylvania, along with the black eagle on blue of the Hungarian voivode (and may even refer to ancient Roman Dacia), and the sun and crescent symbols used by the Szeklers (see above).

Other groups who settled in this region—to make it even more complex!—include the Cumans, fleeing Mongol domination of the steppes north of the Black Sea. All of these groups, Hungarians, Szeklers, Saxons, Cumans, enjoyed a degree of influence and power in medieval Transylvania—the one group who did not, about one-third of the population, were the Romanians, excluded formally from government by the 1350s. Some of these, however, seem to have transformed themselves into Hungarians, converted from Orthodoxy to Catholicism, and joined the power structure. The most famous of these is (probably) the Hunyadi family, based at Hunyad Castle (Hunedoara in Romanian, also called Corvin Castle), one of the greatest landowning families in the region by the 1400s. János Hunyadi, one of the greatest generals defending against the Turks, was named voivode of Transylvania in 1440, and recognised as ‘Prince’ by the pope in 1448. His son Mátyás was elected King of Hungary in 1457, better known as Matthias Corvinus, and reigned for over thirty years, one of the greatest of all Hungarian kings. But the Hunyadi family died out shortly after the death of King Matthias in 1490. It seems an interesting feature of several families surveyed here is that they rose and fell in fairly quick succession.

Going back to the period of direct royal rule of Transylvania, we do have some early dukes rather than princes. Like royal dynasties in western Europe, the Árpád dynasty of Hungary diffused tensions between royal siblings by giving younger sons dukedoms to rule, as premier subjects of their king. Prince Béla, son of Andrew II, was duke of Transylvania from 1226, then succeeded as king (Béla IV) in 1235. His son Stephen was the same from 1257, before also succeeding to the throne (Stephen V). In the later Angevin dynasty, the tradition continued: Louis, son of King Ladislas, was duke of Transylvania, 1339, then succeeded as king (Louis, or Lajos I) in 1342. His younger brother Stephen, was duke of Transylvania from 1349, but also duke of Szepes and Sáros (what’s now eastern Slovakia) and duke of Slavonia, Croatia and Dalmatia, from 1353. He was thus a major potentate in the Balkans, but died only a year later in 1354.

From this point Transylvania was governed by local magnates as voivodes, not dukes or princes. The Szeklers had their own ruler, called the ‘Count of the Székelys’, based at a castle at Gőrgény (Gurghiu in Romanian). But these offices, voivode and count, were merged by the 1460s. Later the Turks would revive the title ‘Count of the Székelys’ for their local administrators, and it was revived again by Empress Maria Theresa in the 18th century. The impetus for the re-emergence of an independent principality came after the Battle of Mohács, 29 August 1526, and the near complete destruction of the Kingdom of Hungary by Ottoman forces under Suleiman the Magnificent. The first to assert the title Prince of Transylvania was János Zsigmond Zápolya (or Szapolyai).

[Nota bene: in Hungarian, you normally reverse the first and second names, but to keep things simple here I will use the more familiar western style.]

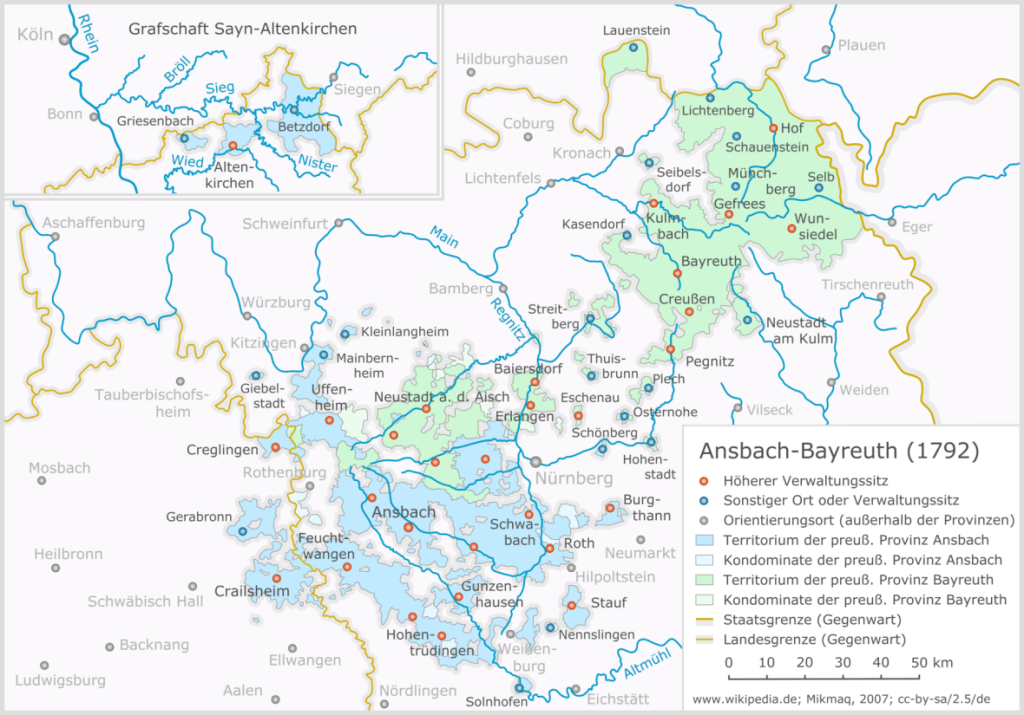

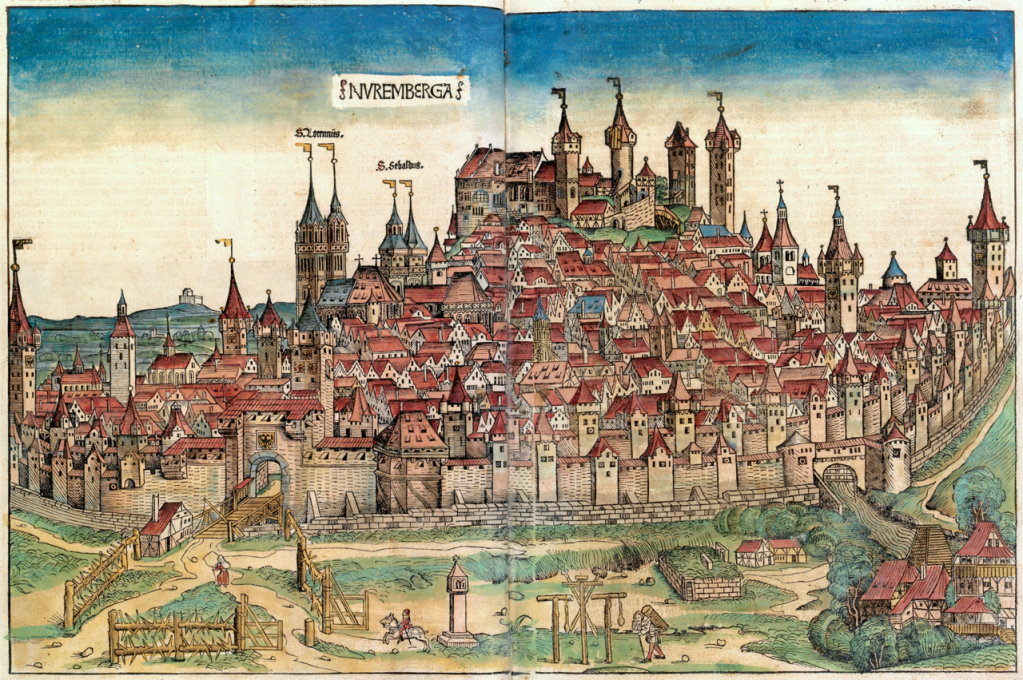

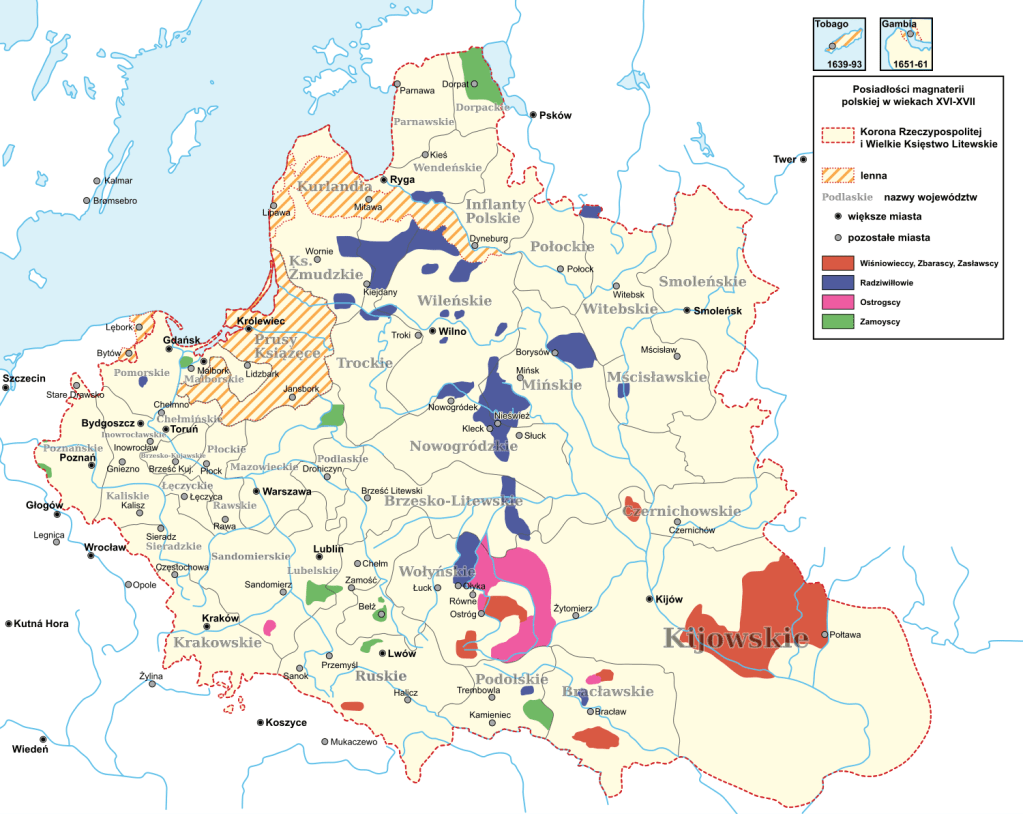

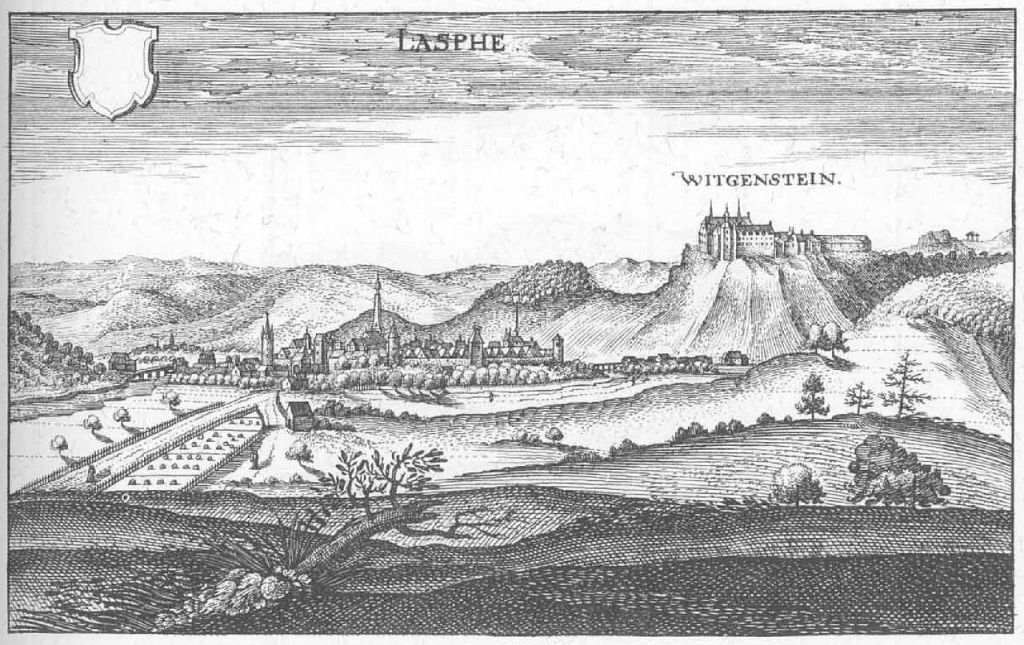

It is unclear where the Zápolya family came from: unlike other Hungarian magnate families they did not trace their ancestry back centuries to the founding of the Kingdom, yet in the mid-15th century, they suddenly emerged as the richest family in Hungary aside from the Hunyadi, to whom they may have been kin. They may therefore also have been originally Vlach, but it seems more likely they were Slavs, taking their name from the village of Szapolya (Zapolje), in Slavonia, on the borders with Bosnia (today in Croatia—Za polja is Croatian for ‘behind the fields’). They gathered properties in Pozsega County (now in Croatia) and Szepes County (now in Slovakia) and by the 1460s, three brothers emerged and took on the most prominent positions in the Kingdom, and formed the core of a ‘nationalist’ party, those opposed to either a Jagiellonian (Polish) or a Habsburg (Austrian) takeover, following the extinction of the previous Hungarian royal dynasty. The eldest, Miklós, was Bishop of Transylvania, based in Gyulafehérvár, from 1462; Imre was the Chief of the Treasury for King Matthias Corvinus, and Ban of Croatia and Dalmatia. A ‘ban’ is a viceroy or governor of a significant territory. The youngest brother, István governed the family’s domains in Szepes County from one of the most powerful fortresses in the Kingdom (Szepes Castle, now Spiš); and also from a second powerful castle a bit further to the west, Trencsén (now Trenčin). This part of Hungary, the mountainous northern section, was known until 1920 as ‘Upper Hungary’, and is today Slovakia. Though not a part of Transylvania, the story of these two regions is tightly interconnected for much of their histories.

As Matthias Corvinus turned his attentions to adding Bohemia and Silesia to his domains in the 1480s, he left Imre Zápolya behind as Palatine (Nádor) of Hungary, basically the regent or viceroy. The King also conquered the duchies of Austria, and left István Zápolya as governor there. István later succeeded his brother as Palatine of Hungary before he died in 1499. He left behind two sons, János and György, who became leading military figures. But the family was also by now linked by blood to the old Polish royal house, the Piasts, and in the early years of the 16th century, would increase their status further through a marriage of their sister, Borbála, to Sigismund I, King of Poland (though she died only a few years later). Sigismund’s brother, Vladislas, was King of Hungary, and appointed János as Voivode of Transylvania and Count of the Székelys in 1510. Not bad for a family that hadn’t even existed a century before.

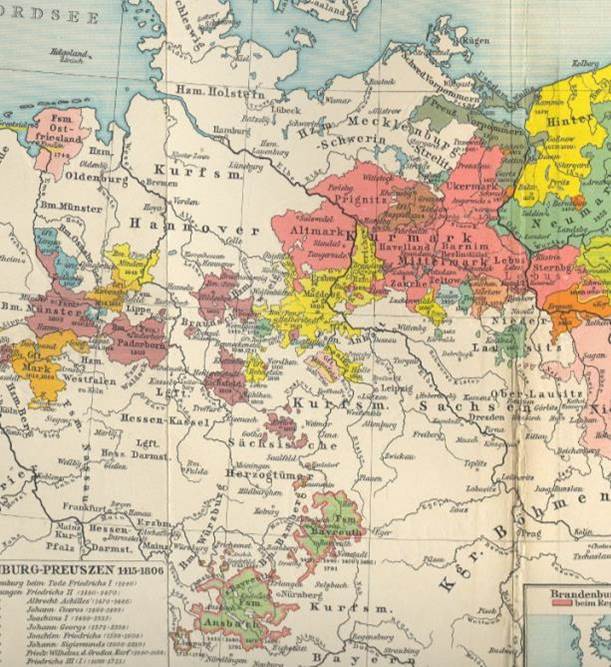

János Zápolya, from his base in Transylvania, led the Hungarian armies against the invading Ottoman Turks in successive campaigns after 1513, and both he and his brother György were commanders of the army at the fateful battle of Mohács, in which much of the Hungarian nobility, and the new young King (Lajos II) himself, were killed or captured. In the void, many Hungarian nobles elected the King’s brother-in-law, Ferdinand of Austria, as new King of Hungary. But a significant group of nobles, mostly the lower nobility and gentry, and those based further from Vienna, in Upper Hungary and Transylvania, voted instead for János Zápolya. His story is thus part of the history of Hungary more generally. From 1529, he made Hungary a vassal state to the Ottoman Sultan, and agreed that the Western part of Hungary (to be known as ‘Royal Hungary’) would be subject to the Habsburgs in Vienna. He solidified his family’s accession into the ‘royal’ world by marriage in 1539 to the daughter of his former brother-in-law (by his second wife), Princess Isabella of Poland. But he died only a year later, leaving an infant son.

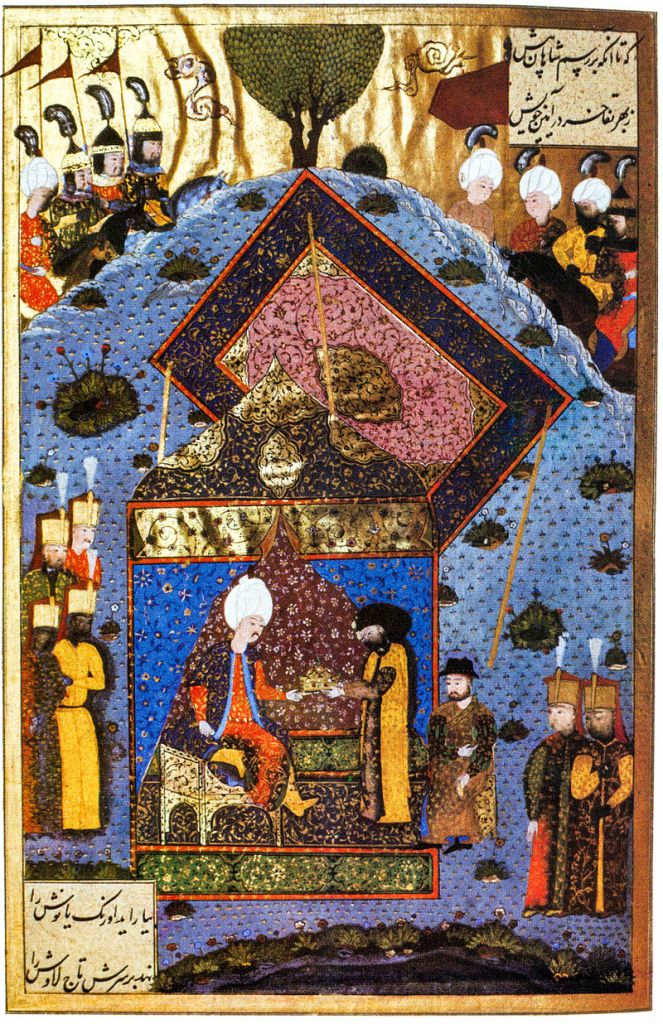

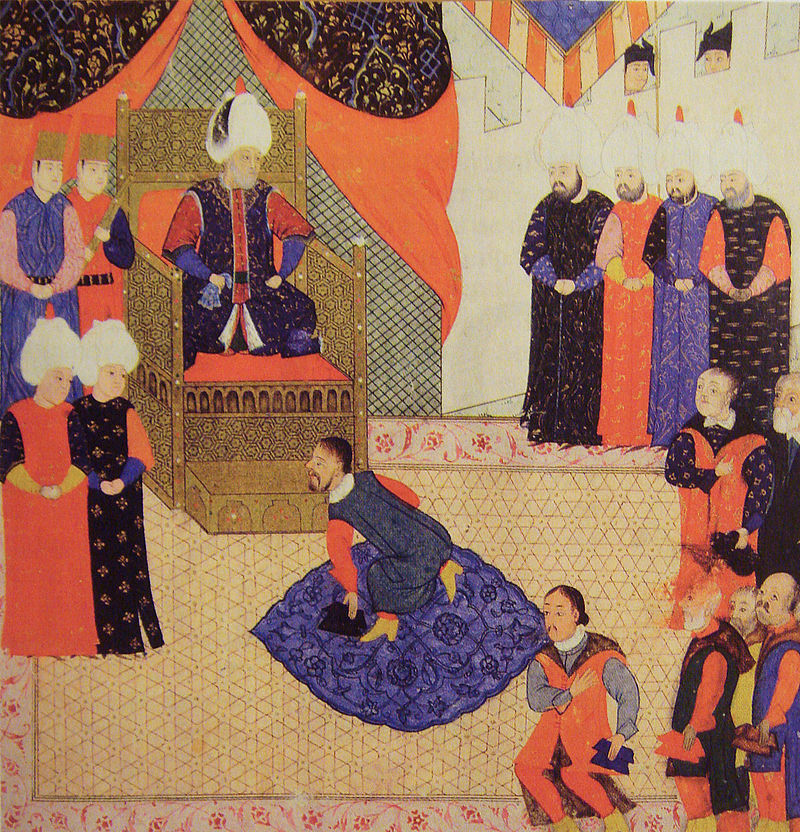

Isabella of Poland was regent for her son King János II Zsigmond, from 1540 to 1551. The Turks took direct control of Buda, so she moved her government to Transylvania and its capital, Gyulafehérvár. In 1551, she and her son briefly ‘abdicated’ and fled to Poland, but were restored to their throne by the Sultan in 1556. Isabella died in 1559, leaving her son fully in charge of his half of the Hungarian kingdom. He placed it formally under the sovereignty of the Ottoman Empire once more in 1566, and did homage to Sultan Suleiman outside Belgrade. In the 1560s, as the Reformation continued to sweep across Europe, János Zsigmond first adopted Lutheranism, then Calvinism, and finally, Unitarianism—making him the only Unitarian monarch Europe has ever seen. Unitarians were also referred to as anti-Trinitarians, rejecting the divinity of Christ. János Zsigmond passed the Edict of Torda in 1568 saying that all people of Transylvania and Eastern Hungary (known as the ‘Partium’) could worship as their own conscience dictated. This was radical stuff! Two years later, by the Treaty of Speyer, he acknowledged that Emperor Maximilian II was King of Hungary, and in return he was recognised as sovereign Prince of Transylvania, a state under the protection of the Ottoman Empire. This first independent prince of Transylvania died only a year later, in 1571. He was succeeded by a Catholic, István (Stephen) Báthory.

Unlike the Zápolyas, or even the Hunyadis, the Báthory clan were amongst the most ancient and distinguished in all of Hungary, and were firmly based in Transylvania and perfectly poised to lead it into a century of semi-independence. They took their name from the town of Bátor, now Nyírbátor, in the far northeast corner of modern Hungary (Szabolcs County), on the borders with western Transylvania. The name is thought to stem from the Old Turkish word ‘batir’ (or even a Mongolian word, ‘bator’), originally meaning a ‘good hero’, and corresponding to ‘bátor’ in modern Hungarian.

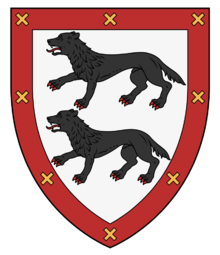

The Báthory family emerged from one of the ancient clans of the Hungarian tribes known as the Gutkeled, though legend places the origins of this group as two brothers from Swabia, not Magyars, Gut and Keled, who emigrated to this area in the 1040s. Whatever their origins, they rose to great prominence in the period of the decline of the first royal dynasty in Hungary: István of Clan Gutkeled was Palatine of Hungary from 1246, and Ban of Slavonia from 1248—he established almost an independent state here, based in Zagreb, and took the title ‘Dux’ in 1254. When he died in 1259, his four sons took over in various powerful and semi-independent positions in the Kingdom, with Joachim in particular leading a rebellion against King Stephen V in 1272, and taking over as Guardian and Tutor of the new young king, Ladislas IV. This was the start of a period known as the ‘feudal anarchy’ when magnates basically ran the Kingdom as independent petty princes. The Árpád dynasty collapsed and then went extinct in 1301, and order was only restored with the accession of the powerful Charles of Anjou and the defeat of his rivals in 1308.

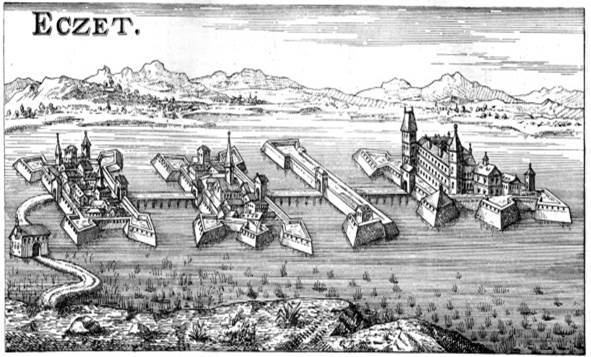

By this point, the Gutkeled Clan had divided into various sub-lineages, who started to adopt surnames based on their key properties (though they would continue to share the same or similar coats of arms). One of these was Briccius or Bereck, who was given Bátor in 1279 by Ladislas IV as thanks to him and his uncles for serving him in the magnate wars. Eventually the Báthory family split into two branches: one based in Somlyó (or Szilágysomlyó, today’s Șimleu Silvaniei, in Transylvania); and one in Ecsed (now Nagyecsed in northeast Hungary—this was the burial place of many members of the family, including the famous Countess Elizabeth Báthory). There is another family with a similar name, Báthory de Gagy, who were part of the Clan Aba, another one of the very early Magyar clans, who will come up again below.

The junior branch, at Castle Ecsed, rose to greater prominence first. In the early part of the 15th century, István Báthory held several important court and government offices, notably Master of the Stewards, 1417, and Chief Justiciar of Hungary, 1435. His four sons were pillars of the reign of King Matthias Corvinus: Master of the Horse, Master of Stewards, Master of the Treasury, Chief Justiciar and Bishop of Vác (a chief royal counsellor). In 1479, István was named Voivode of Transylvania. His nephews were also prominent in the era of the Battle of Mohács, where one of these, György, Master of the Horse, was killed. The eldest, another István, was at the time the Palatine of Hungary, and he became one of the leaders of the pro-Habsburg faction after Mohács, organising the election of Archduke Ferdinand at Pozsony (now Bratislava). The Turks confiscated his lands, so Ferdinand gave him the Castle of Dévény (now Devin), a powerful fortress that guards the entrance to that city.

As we saw with the Zápolyas, István Báthory wanted to raise up his family’s status by marrying royalty: he married a Polish princess, Sophia, a potential heiress to the Duchy of Mazovia. They had no sons, however, so family leadership passed to three nephews, who again dominated court offices and regional administration, still loyal to the Habsburgs: the eldest, Bonaventura, was Master of the Treasury, Voivode of Transylvania and Chief Justiciar in the 1540s-50s. He was virtual ruler of the Kingdom of Hungary in a period when the Turks were pushed back (the 1550s).

Ecsed remained the family’s nearly impregnable base. The castle had been built by this branch of the Báthorys in the 1320s, on an island in a bog, not too far from the town of Bátor. A dragon was said to patrol this bog, and by some accounts it is this dragon’s teeth, pulled out by one of the warrior ancestors, that adorn the Báthory coat of arms.

Ecsed was considered to be one of the most impregnable castles in the Kingdom. From here, Bonaventura’s nephew, yet another István, Chief Justiciar from 1586, governed Szabolcs and Szatmár counties. His eldest sister, Erzsébet (Elizabeth), was raised here, and became his chief heir in 1605, though she resided at her late husband’s castle of Csejte (now Čachtice, Slovakia). Her reputation as the ‘Blood Countess’, that she bathed in the blood of hundreds of murdered virgin peasant girls, is based on accusations by her powerful neighbours—in particular her Thurzó cousins, who coveted her extensive lands—and fuelled by the Habsburg dislike of her Calvinist faith and excessive wealth. She was confined to house arrest in her castle in 1611, and died in 1614.

Ecsed and the other lands of this branch passed to the Somlyó branch, then to the Crown, which re-granted it to the Bethlen family, then to the Rákóczi family, both of whom will feature in the later sections of this blog. It remained an impregnable fortress and a centre of rebellions, until it was finally taken over by Emperor Leopold in 1711 and completely destroyed. There is apparently nothing left.

So we need to switch back to the senior branch, Somlyó, and to the story of Transylvania itself. This castle was acquired by marriage in 1351, and rebuilt as Báthory Castle in the 1590s. The town today remains about 30% Hungarian and 25% Calvinist.

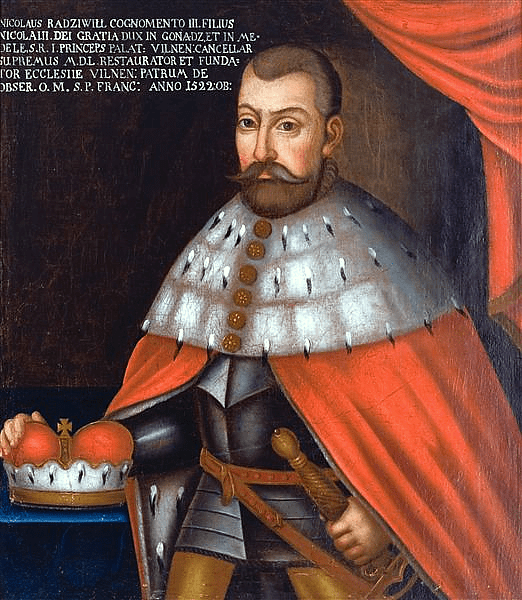

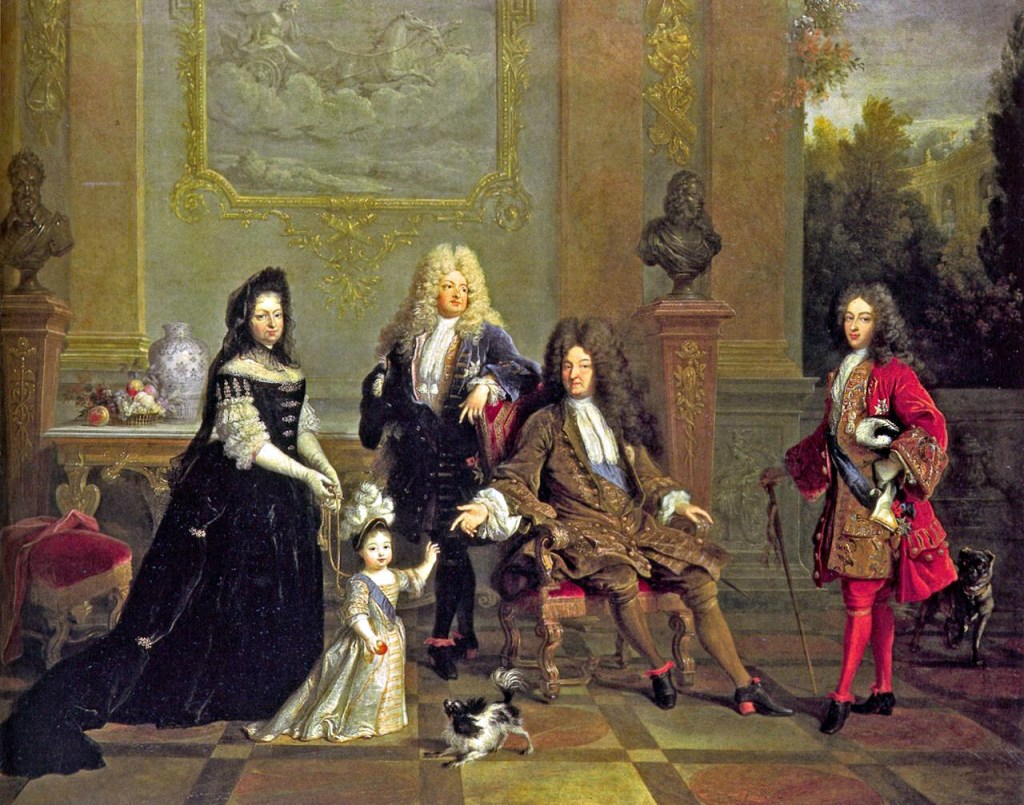

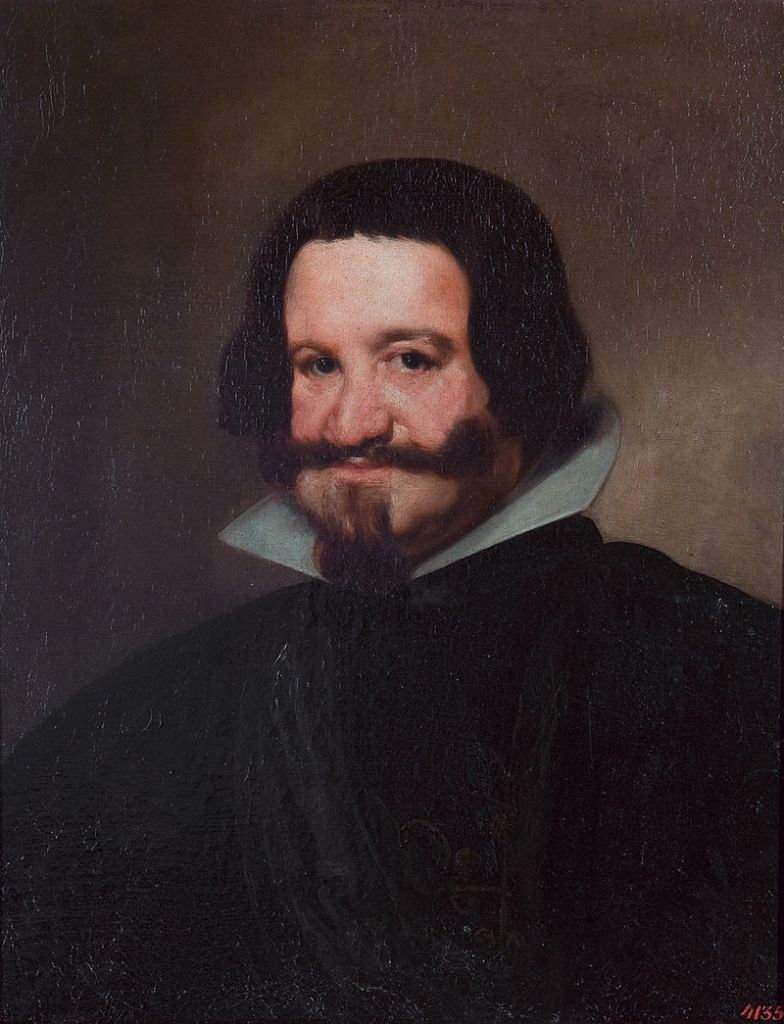

In 1530, István Báthory of Somlyó was named Voivode of Transylvania by János Zápolya, Unlike his kin from the Ecsed branch, he did not support the Habsburg election after the Battle of Mohács. His son, István—the most famous István Báthory, with an international reputation, so I’ll call him Stephen—initially did fight for Ferdinand, but was captured by the Turks in 1553, and, the Habsburg king refusing to pay his ransom, promptly switched sides. When János II Zápolya, Prince of Transylvania, died in 1571, the magnates elected Stephen Báthory voivode, not prince, though he assumed that title later. Báthory was now seen as one of the most powerful magnates in the east, and was elected in 1575 to become King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania, in an effort to stop the expansion of Habsburg power. He agreed to marry the last Jagiellonian princess, Anna, in 1576, and left for Poland, leaving his older brother Kristof behind as Voivoide of Transylvania. King Stephen, a Catholic, re-affirmed the policy of religious tolerance in both of his realms, Transylvania and Poland-Lithuania, and wanted to use Polish power to restore an independent Hungarian kingdom. Instead, he was occupied with war with Russia for many years, weakened, and died in 1586. His widow, Queen Anna, had considered promoting his nephew Zsigmond Báthory as the next king in Poland, but instead supported the election of her own nephew, Sigismund Vasa.

Zsigmond, Kristof’s son, had been named Voivode of Transylvania by his uncle in 1581 (though he was only 9 years old), and succeeded him as Prince of Transylvania in 1588. His reign was turbulent to say the least. He was governed by his uncle, István Bocskai, and was confirmed as prince by Sultan Murad III, in return for a 15,000 florin yearly tribute. Rejecting his mother’s Calvinism, Prince Zsigmond was a fervent Catholic, which made him unpopular with the local Transylvanian nobility. Making matters worse, he decided to challenge Ottoman suzerainty, ignoring the advice of his Báthory cousins, who, despite being strongly Catholic, did not think it wise to provoke the Ottomans without the full support of Poland. Imprisoning these cousins (and even executing one of them), in 1594 Prince Zsigmond joined the Holy League set up by the Pope and the Emperor, Rudolf II, to push the Ottomans back down the Balkans, and married the Emperor’s niece, Archduchess Maria Christina, in 1595. He was created Prince of the Empire in 1595 as well, and recognised by the Emperor as hereditary Prince of Transylvania and ‘Partium’ (the easternmost counties of Hungary). He even, for a moment, got the voivodes of Wallachia and Moldavia (the Romanian provinces subject to the Ottoman sultan) to acknowledge him as suzerain. Together they defeated the Ottomans at the Battle of Giurgiu, on the Danube along the border with Bulgaria, in October 1595. This was the high point of the independent Principality of Transylvania.

This was followed, however, by lots of defeats, and Zsigmond abdicated in 1598. Maria Christina was elected herself as Princess, until Archduke Maximilian of Austria arrived in 1599 to rule the territory directly as a province of the Habsburg Monarchy. Her marriage, never consummated for whatever reason (Zsigmond claimed he was bewitched; later historians suggest he was a homosexual), was dissolved. The Ex-Prince fled to Poland where he was given lands to rule in Silesia (Ratibor and Opole). He tried to return in 1599 to make a deal with the Sultan, but failed and abdicated again, then returned again in 1601 with a Polish army and briefly got the support of the Sultan, but was unable to establish stable rule, so he abdicated once more, now in favour of Emperor Rudolf. He settled in Bohemia (at Libochovice, in the far northwest), resisted several calls from the Emperor to try again to recover Transylvania, and died in exile in 1613. Maria Christina did not remarry but joined a convent back in Austria, where she died in 1621.

In the midst of all this, Prince Zsigmond had appointed his cousin András Báthory as Prince of Transylvania, in March 1599, with the support of Polish and Ottoman troops. A Cardinal since 1584 (nominated by his uncle, King Stephen—and at once point considered as a possibility to succeed him as king in 1586), and prince-bishop of Warmia in Poland since 1589, he was firmly on the side of the Poles and the idea of re-catholicising Transylvania. He did re-establish the Catholic diocese in Gyulafehérvár, which remains today, but his rule as Prince of Transylvania lasted only a few months. The Habsburgs allied with the Prince of Wallachia (Michael the Brave, or Mihai Bravu in Romanian) and with the Székely peasants who always seem to get dumped on and had had enough, and in October 1599, the Polish-Ottoman troops of Prince-Cardinal András were defeated at Sellenberk (Șelimbăr near Sibiu, in the south-eastern corner of Transylvania). András was beheaded, and power was given to Prince Michael. The battle of Șelimbăr is seen today as the first moment leading to the unification of the Romanian people.

The Báthorys were not completely finished as a ruling dynasty, however, and we will return to Prince Gábor Báthory in a bit. First we have a quick succession of princes: Mózes Székely, István Bocskai and Zsigmond Rákóczi.

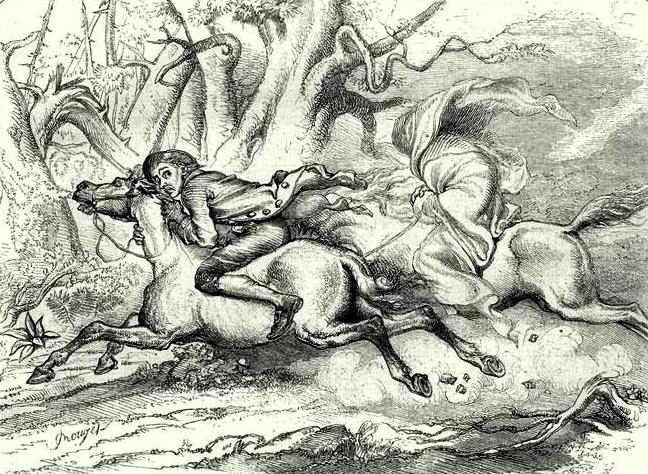

Mózes Székely was, as his name suggests, a Székler. His family was from Székelyudvarhely (now Odorheiu Secuiesc) in the eastern corner of Transylvania. It had been the seat of the Székler assembly since the 1350s, and the seat (‘szék’) of Udvarhely County. The family’s estates were centred on Siménfalva, a town still today 99% Hungarian and mostly Calvinist or Unitarian. His father had been a regional supporter of Zápolya and converted with him to Unitarianism in the 1560s, and was given the job of controlling the production of salt in this region, an important commodity. Young Mózes became a commander of the Székler guards of Stephen Báthory in the 1570s and accompanied him to Poland. He was granted estates back in Transylvania and took over his father’s post overseeing the salt mines, and defending the region against Turkish attacks in the 1590s. He helped restore Zsigmond Báthory in 1598, still leading the Székler army, but these turned on András Báthory and murdered him, as we’ve seen. Mózes became commander of the Habsburg troops in Transylvania, 1599, under the command of the Wallachian prince, Michael, but when the latter’s regime started to collapse in 1600, he travelled to Poland to try to bring about another Báthory restoration. When the Habsburgs regained control once more, Székely instigated a rebellion, 1603, with Turkish and Tatar aid, and in May claimed the title Prince of Transylvania. Again the Skékeler people allied with the Wallachians (who promised them a larger role in government), and they defeated and killed their former leader in July. So much for being the local boy.

Mózes Székely Jr was born a few days later. Raised by a Bethlen grandmother, he was put under the protection of a later Transylvanian prince, Gabriel Bethlen, who appointed him Master Steward of the Household, Justiciar of Udverhely County (1620), then gave him lots of estates and married him to a wealthy heiress. All of this was taken away from him by Prince György Rákóczi, however, in the 1630s, and Székely went into exile in the Ottoman Empire. As a prisoner/guest of the Sultan in Constantinople, he spent the next two decades as a diplomatic chesspiece, always a potential claimant to the Transylvanian throne to be wheeled out as needed. But he eventually lost his value, and the Turks sent him to live on the Island of Rhodes where he died in 1657 or ‘58.

A more successful story was that of István Bocskai. His family was from Bihar County in western Transylvania, and also had lands in Zemplén County, which is now eastern Slovakia (near the border with Ukraine). His older sister married the Voivode of Transylvania appointed by Ferdinand of Austria in 1553 (István Dobó), and young István was sent to the Habsburg court in Vienna where he served as a page, then a steward. His father converted to Calvinism in the 1560s, then died in 1570, leaving the teenager in the care of another sister, who married Kristof Báthory, the regent of Transylvania for his brother King Stephen (whom we encountered already above). The two families were therefore fairly entwined, so even as a youngster in 1581 (aged 14), Bocskai was appointed a member of the Regency Council for his nephew young Prince Zsigmond Báthory (aged 9). He married a wealthy widow with lands in Bihar County (the great fortress at Nagykereki), and was appointed governor (ispán) of that county by 1592. He helped Prince Zsigmond throw off the Turkish yoke in 1593-94, then led his armies to defeat the Ottoman forces in Wallachia in 1595 and put down a revolt of the Széklers in 1596.

By 1598 István Bocskai was crucial as an interlocutor between Prince Zsigmond and Emperor Rudolf II (who created him a Baron—a rare creation of a noble title for Hungarians who normally considered that a family name was honour enough). Then when Zsigmond abdicated, Bocskai was left behind as his viceroy. Rudolf changed his opinion of his ally however, and deprived him of this office, so the latter helped restored his Báthory cousin in 1599. The tables soon turned again, and Bocskai was sent to Transylvania as the Emperor’s envoy to unseat the pro-Ottoman Prince András. He therefore wanted to be recognised by Rudolf and perhaps rewarded with the voivodeship or even the title of prince, so he pressed his case in 1600, and the local diet confiscated his estates and banished him. He spent much of 1601-02 at the imperial court in Prague as a counsellor to Rudolf II, and was restored to his estates in 1604. He returned to the area to find the destruction of Transylvania caused by the Habsburg-Ottoman wars, and in particular the persecution by the Habsburg governors of the Calvinist nobility (like himself). He realised that only a free (Ottoman supported) principality would thrive, and launched the great Bocskai Uprising (or ‘war of independence’). In November 1604 he was given an ahidnâme (charter) from Sultan Ahmed I naming him Prince of Transylvania. He made peace with the Széklers and allied with the Prince of Moldavia. In February 1605, he was elected Prince of Transylvania by the local diet; this was confirmed by an assembly of nobles from Upper Hungary in April. At the height of his power, Prince István Bocskai asked the Sultan for a royal crown, for all of Hungary, and got one. He was styled as ‘King’ by the Pasha in Buda. This crown is still kept in the royal treasury in Vienna.

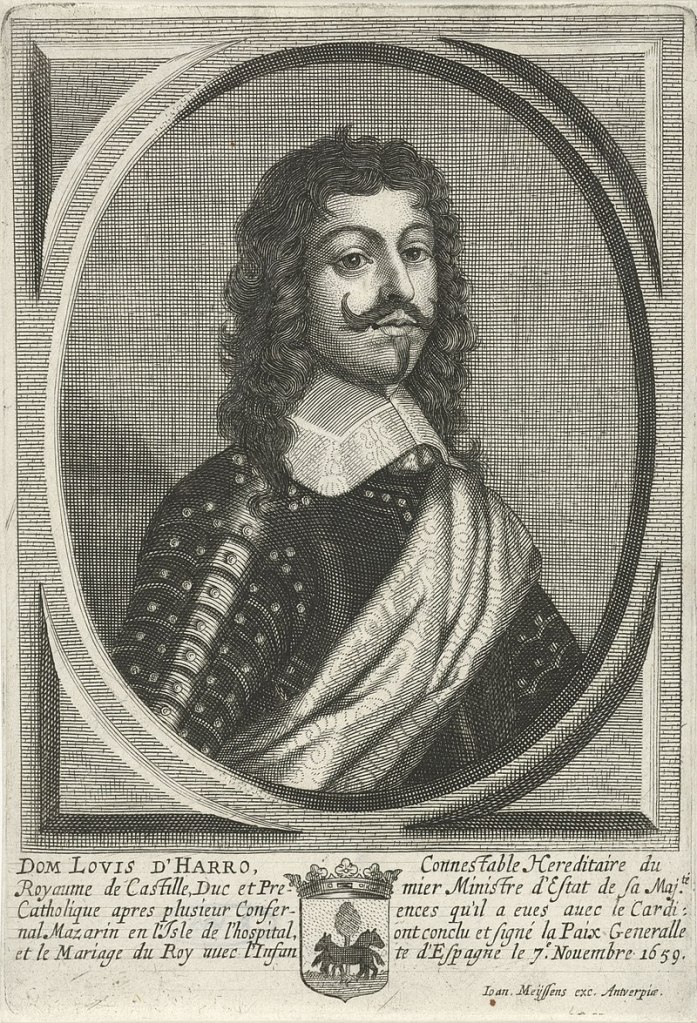

By the Treaty of Vienna, June 1606, Bocskai was confirmed as Prince of Transylvania (with the Ottoman sultan as suzerain), and the Emperor recognised the rights of Protestants to worship freely across Hungary. The Prince then helped negotiated a long-desired peace between the Habsburgs and the Ottomans in November at Zsitvatorok. But by this point Prince István was weary and ill, and he died in December. He had no children from his late wife (though he had considered marrying the widowed Archduchess Maria Christina), and named a successor, one of his companions in arms, Bálint Drugeth, but the Transylvanian Diet chose someone else instead, a very wealthy older man, whose loyalties were neither to the Ottomans nor the Habsburgs: Zsigmond Rákóczi.

The name Rákóczi is of course for many synonymous with Hungarian history. The ‘Rákóczi March’ is quite a well-known tune—though not written till the 1820s, and made famous soon after through its use by Hector Berlioz in his ‘Damnation of Faust’ (and later by Liszt in one of his Hungarian Rhapsodies). The family traces its lineage back to the 13th century, and the Bogátradvány family, whose origins were said to be from Bohemia (why do none of the Hungarian magnates seem to have actually Magyar ancestry?). An early notable ancestor from this clan was Ipoch, Ban of Slovenia from 1204, and Voivode of Transylvania in 1216-17. By the early 14th century, a descendant took his surname from a castle called Rákóc, in Zemplén County (now in eastern Slovakia), which may have been named for the Slovak word for crayfish (rak; the village today is called Rakovec).

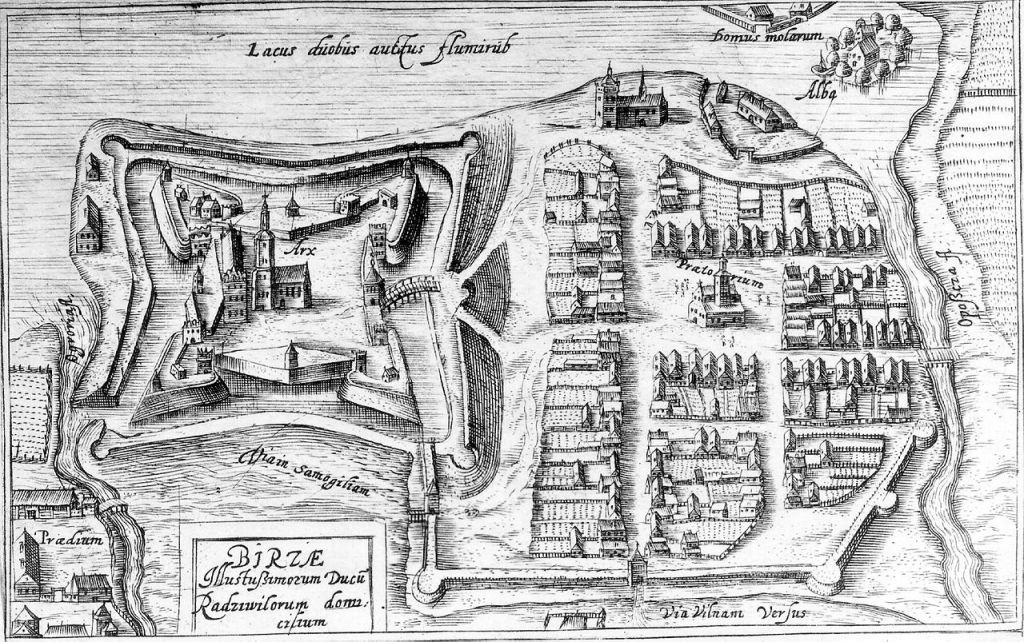

They remained a fairly minor gentry until they shot to the top with the rise of Zsigmond Rákóczi in the second half of the 16th century. He owned lands in the Tokaj wine region of Zemplén County, and built up a family seat in the 1550s at Szerencs Castle. This remained the seat of the Rákóczi family, and a seat of Calvinism in this part of Upper Hungary, until the early 17th century. In the 18th century Szerencs was rebuilt as a palace, and today it is a hotel, a museum and a town cultural centre.

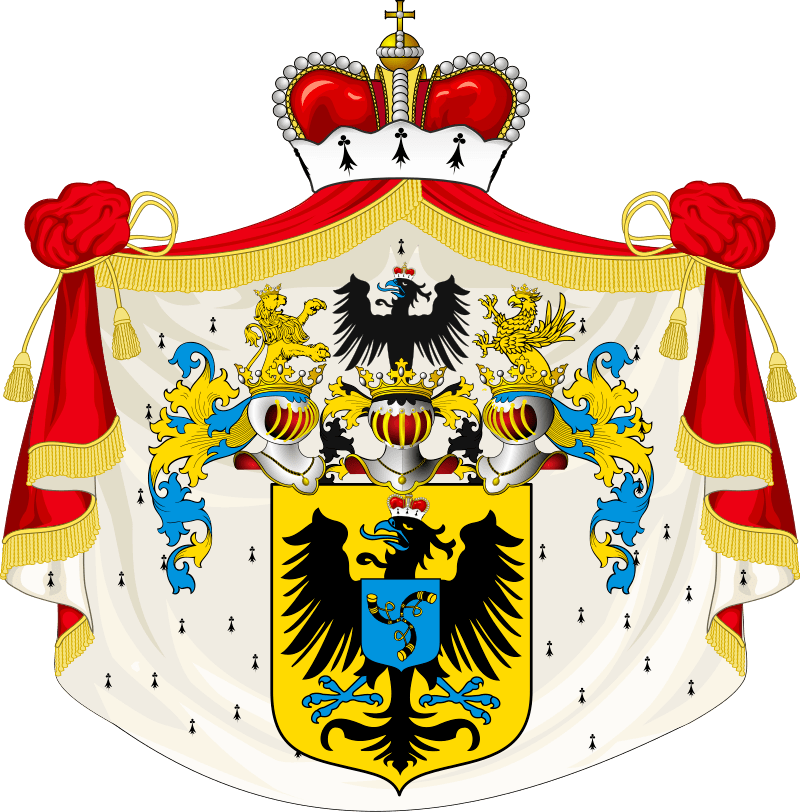

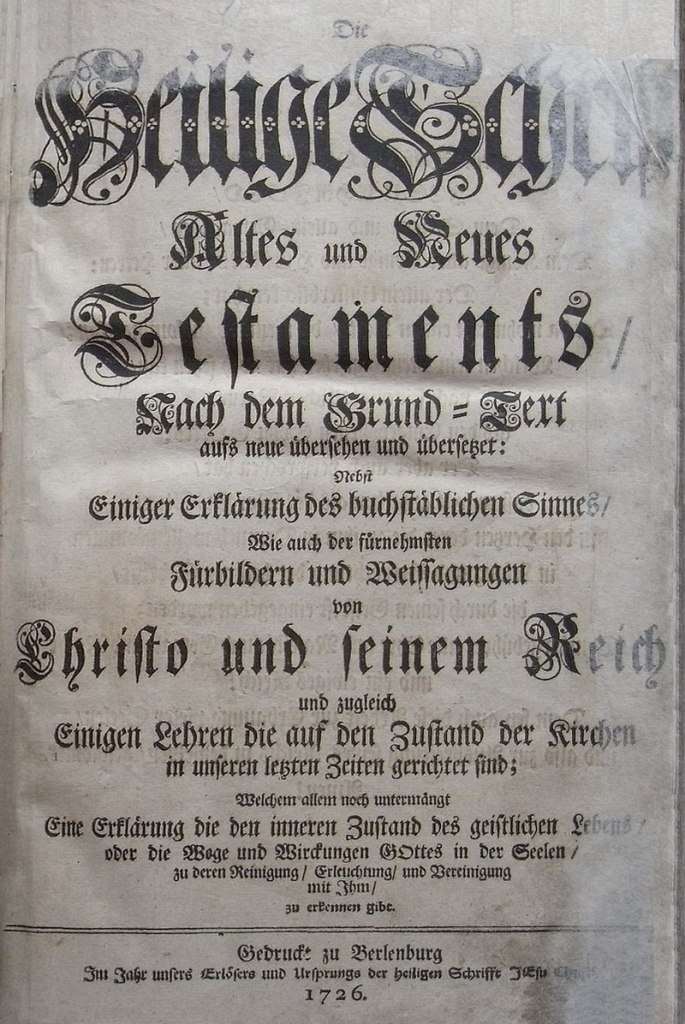

Zsigmond’s early career was in the Habsburg military, and he later served as a tax collector for Emperor Rudolf. By the 1590s, he was an important Habsburg commander in the region, despite his Protestantism, and was given command of the huge fortress of Eger, in Heves County, northeast of Buda. He was named Lieutenant of Heves County in 1588 and made a Baron. His wealth was prodigious, and he supported local Protestant schools and the first translation of the Bible into Hungarian. He even lent money to the Emperor for troops, and in 1597 was given the right to bear the Imperial eagle on his coat of arms, instead of the traditional Rákóczi raven. He continued to build his fortune particularly in the far northeast frontier, taking over Munkács Castle as guardian of his wife’s sons, then Makovica Castle from the bankrupt Ruthenian Prince Ostrogski.

Munkács will feature more in the next sections. Makovica, also known as Zboró (Zborov in Slovak), was an important fortress in Upper Hungary, near the frontier with Poland and guarding some of the key passes across the Carpathians. Built in the 13th century it was held by the Czudar family for a century before becoming Crown property, then passed through various proprietors before being purchased in 1601 by Zsigmond Rákóczi. It became one of the main strongholds for the family in the century to come before it was destroyed by Habsburg forces in 1684. Rebuilt and destroyed again and again in the next two hundred years, it remains a romantic ruin today.

Now one of the richest men in Hungary, and possessing some of its strongest fortresses, Zsigmond Rákóczi became disillusioned with Habsburg rule in Transylvania and Upper Hungary, and joined the Bocskai Uprising in Spring 1605. He was named governor of Transylvania by the rebellious prince in August. His wealth and his control of key trade routes north towards Poland made him an invaluable magnate to the health of Transylvania, so it was not too surprising that he was elected Prince of Transylvania by the Diet in February 1607. He was acknowledged by the Ottomans, but not by the Habsburgs. Bocskai’s preferred successor Drugeth threatened a civil war, as did the Habsburg choice, Gábor Báthory, so Rákóczi abdicated in March 1608 to avoid more bloodshed. Well into his 60s, he did not have the energy or the desire to rule, and in fact he died only a few months later and was buried back in the Calvinist chapel in Szerencs.

Gábor (or Gabriel) Báthory, of the Somlyó branch of Báthorys, was born a Catholic, but was orphaned and raised by his Protestant cousin István Báthory from the Ecsed branch. When the latter died in 1605, Gábor inherited his lands, and thus joined together the possessions of the two lines, becoming one of the richest magnates in Hungary. He was also willed much of the lands of his cousin István Bocskai, so saw himself as the most logical successor when he died in December 1606. He gained the support of the Habsburgs by promising to re-convert to Catholicism (though he never did). He put forward his claims to the elderly Rákóczy in February and was elected by the Diet in March 1608, and was soon recognised by both the Sultan and the Emperor.

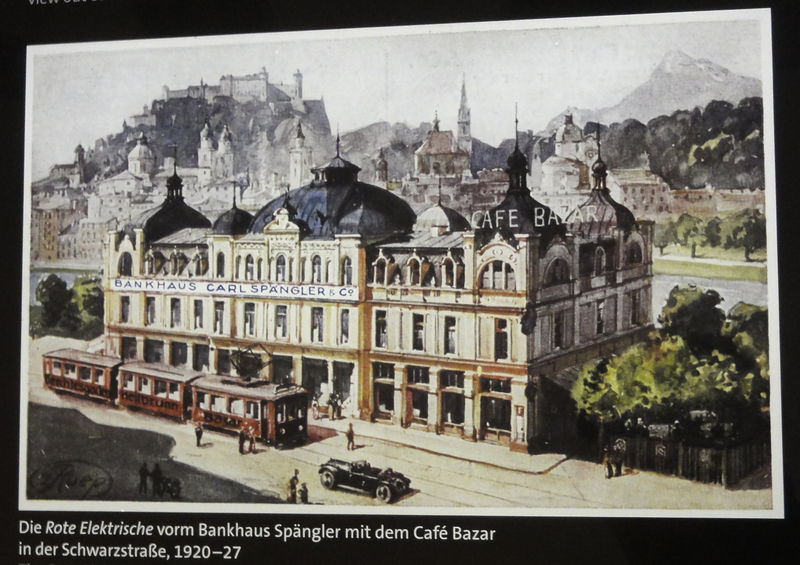

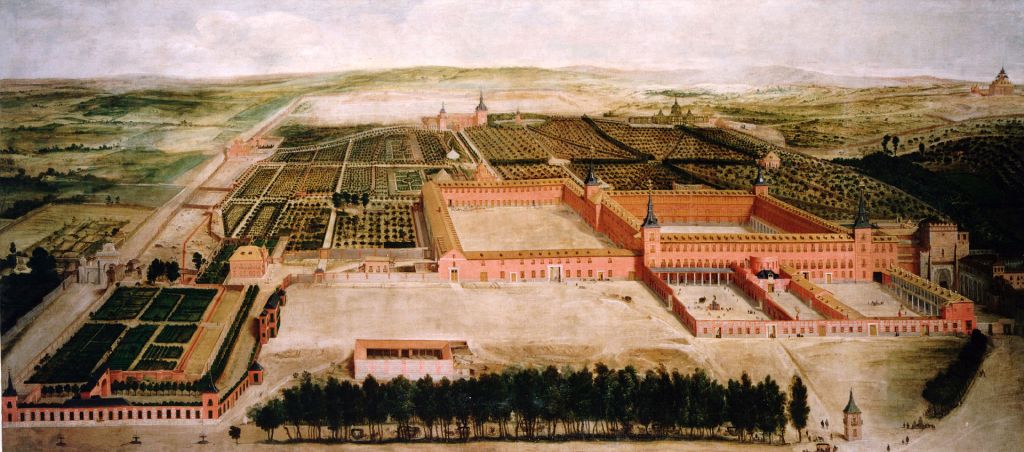

In 1610, the new Prince of Transylvania moved his capital from Gyulafehérvár, so badly damaged during the wars, to Szeben, the richest Saxon town in the region, known by them as Hermannstadt (and today as Sibiu in Romanian). Hermann was probably an early German founder of the settlement—it remained majority German, and Lutheran, until after the Second World War, but today following mass emigration has almost none of its former diversity.

Perhaps feeling a bit over-confident, Prince Gábor Báthory tried to extend his influence over the other two dependent principalities, Moldavia and Wallachia, greatly annoying the Sultan, Ahmed I, who sent troops to unseat him, in August 1613, and to replace him with another Gábor, from the ancient Bethlen dynasty. The last Báthory prince was murdered by assassins from the famous group of Hungarian soldiers known as the Hajdúk. One further member of the family, András, stayed mostly out of sight until he died in 1637, leaving one daughter, Zsófia, who would re-connect this ancient family to the Rákóczys and the future history of Transylvania.