One of the most persistent and popular legends in the history of eastern Europe, and in the steep Carpathian Mountains of Transylvania, is the story of an undead prince, a vampire, the ultimate blood-sucker, Count Dracula. His purported residence, Bran Castle, is the top tourist destination of Romania, with hundreds of thousands of visitors per year. Yet a quick scan of internet sites devoted to the famous prince of darkness reveals that the character created by the British novelist Bram Stoker in 1897 has almost no relation to either Bran Castle or with the notorious warrior prince, Vlad the Impaler, on which Stoker is thought to have based the character.

So who was Vlad the Impaler? For starters, although much of his history is indeed connected to the Principality of Transylvania (about which I wrote two lengthy blog posts earlier this year), the main territory over which he ruled was the neighbouring Principality of Wallachia. As he is known in Romanian, Vlad Țepeș, or Vlad III, was Voivode (duke or prince) of Wallachia in the mid-15th century, and was infamous even in his own time as a particularly cruel warlord who beheaded and impaled his enemies by the thousands. The name Dracula came from his father, Vlad II ‘the Dragon’, and this branch of the family—the Basarab Dynasty—were known as the Drăculești, the House of the Dragon.

This post will focus on the Basarab Dynasty as rulers of Wallachia, one of the three principalities that eventually made up the Kingdom of Romania in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Over 300 years, from the early 14th century until they died out in the mid-17th century, the Basarabs were an incredibly violent dynasty in an incredibly turbulent region, on the front lines between the Christian West and the Islamic East, between the Kingdom of Hungary and the Ottoman Empire. Modern nationalist defenders of the extreme cruelties meted out by warlords like Vlad the Impaler and others of his family argue that such measures were essential in order to achieve regional independence in the face of much more powerful neighbours.

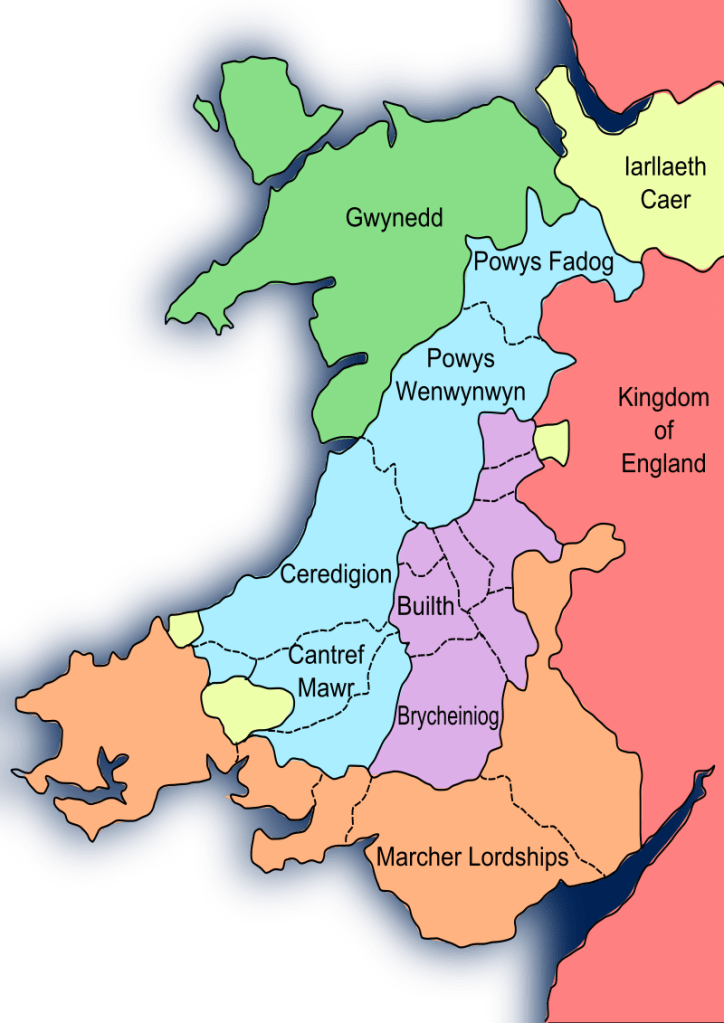

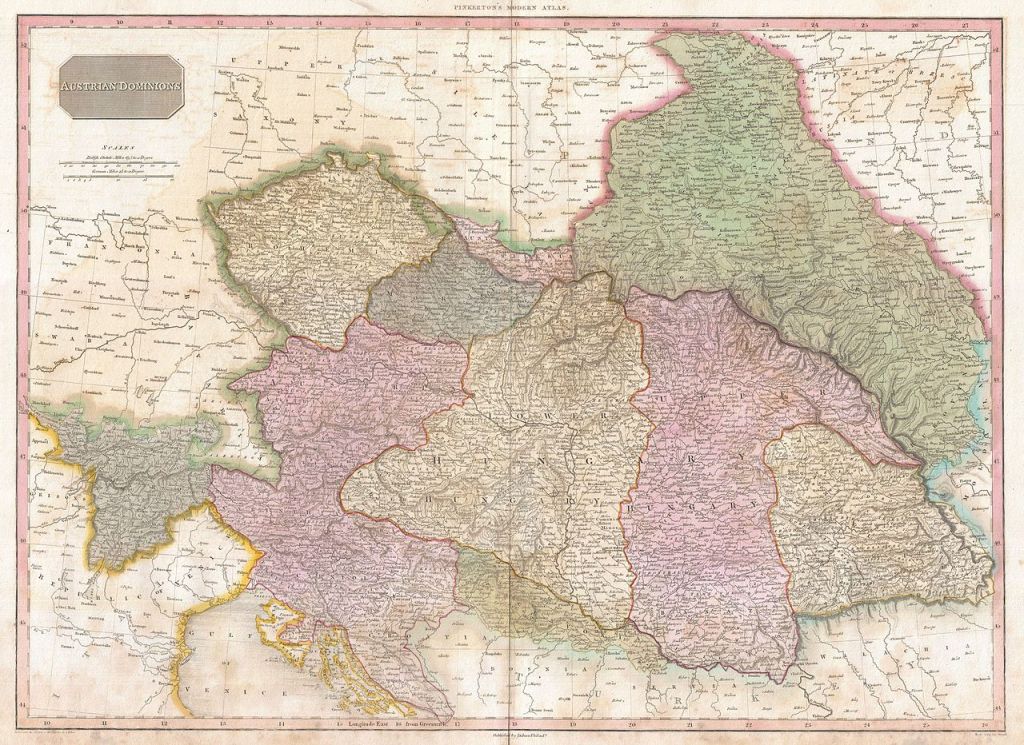

Wallachia is the southernmost of the three Romanian principalities. Occupying a broad plain bounded on the north by the Carpathians and on the south by the broad river Danube, it formed part of the Ancient Roman province of Dacia, and retained a Latin-based Romance language through the centuries when most of the surrounding lands became increasingly Slavicised. In fact, their own name for this region is Țara Românească (‘the Romanian Land’); whereas Wallachia comes instead from the name given by non-Romanians to outsiders, from the ancient Germanic term for ‘other’ (walhaz—which also gives us Welsh and Walloon). In the past, the country was referred to as Vlahia, Wlachia, or Valahia, and the people as Vlachs. Bulgarian Slavs called it Vlashko, while Turks added a vowel at the start to form Eflak. The Hungarians—often the overlords, extending their rule across the mountains from Transylvania—called it Havasalföld, or ‘Snowy Lowlands’, or sometimes Ungrovlahia. Hungarian kings took control of this area of the lower Danube valley in the late 900s (from the Bulgarians), and ruled jointly with their Turkic allies who had settled from the eastern steppes, the Cumans (sometimes the King of Hungary also added the title ‘King of Cumania’). But this coalition was destroyed by the Mongol invasions of the 1240s, and afterwards the region was divided between Hungary north of the Danube and Bulgaria to the south. They appointed local Vlach lords to act as governors or voivodes. This Slavic term literally means ‘war lord’, but has also been translated as ‘duke’ (which also originally meant a leader of troops) and sometimes as ‘prince’. Wallachian rulers were also called hospodar, another Slavic word for lord, and in Romanian domn (from Latin dominus). All of these terms implied a degree of autonomous rule, but usually as a vassal to a greater power.

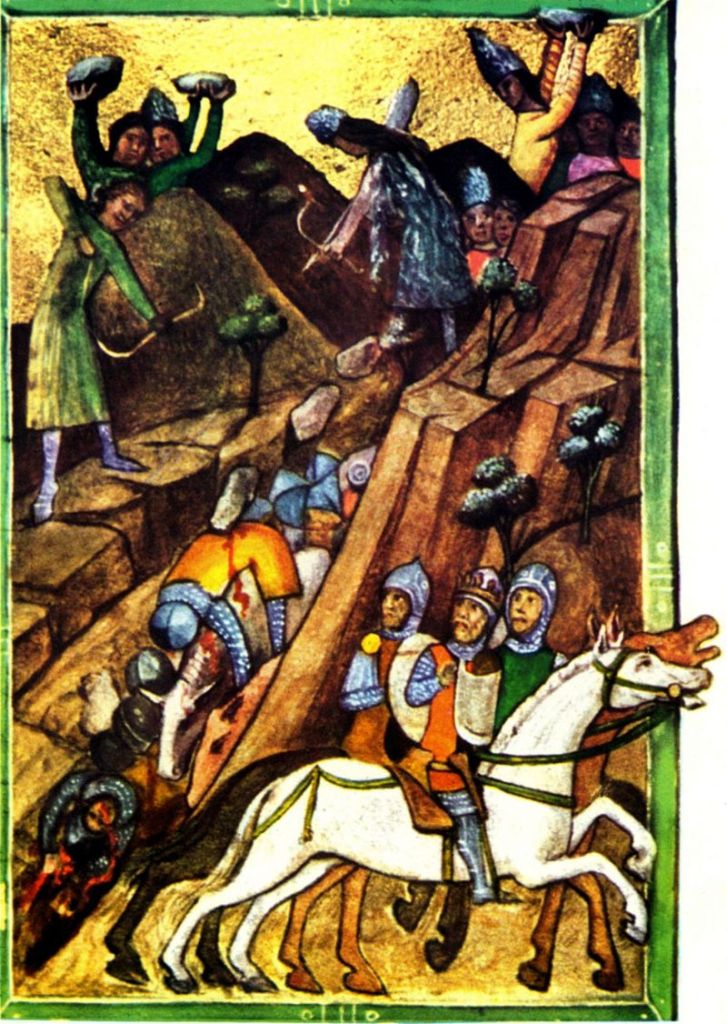

The first known Wallachian voivodes were appointed by the King of Hungary in the 1240s-1280s. Some ruled in the western part of the region, known as Oltenia (west of the River Olt); and others ruled in the east, Muntenia (‘mountains’). Historical records first refer to ‘Wallachia’ as a whole under the voivodeship of Seneslau, whose name is thought to be Slavic, Seneslav, but who is specifically referred to as a Vlach. Other Vlach names are similarly reflective of the mixed ethnicities in this region: Seneslau’s possible son, Tihomir (Thocomerius) could take his name from toq-tämar, Turkic (or Cuman) for ‘hardened steel’; while Tihomir’s son’s name, Basarab, could also be of Turkic origin, as basar aba, ‘ruling father’. Basarab is considered to be the first verifiable historical figure, appointed voivode in about 1310, but rebelling against Hungarian rule and establishing his own autonomy by about 1325. The King, Charles of Anjou, tried to retake the province by force in 1330, but was defeated at Posada, in the mountains separating Transylvania from Wallachia, in one of those epic nation-building foundational battles in which a small force of local warriors and peasants fight off a much larger foreign army. Basarab is therefore known as ‘the Founder’ and gave his name to the Wallachian dynasty that followed (and also, more tangentially, to the region further to the east known as Bessarabia, now Moldova).

Basarab may also be the historical version of a more legendary figure, Radu Negru (‘the Black’), who supposedly founded a new Wallachian capital at Câmpulung—‘long field’, the site of an ancient Roman colony, Campus Longus. Radu itself comes from the Romanian word for ‘joy’ and it will be one of the most common names used in the dynasty (and indeed throughout Romania today). Not much is known about Basarab I. Was he Orthodox, in opposition to Hungary’s Catholic king? For about 25 years, he ruled Wallachia as an ally of Bulgaria, against its enemies the Serbs and the Byzantines. This alliance was sealed through marriage, and his daughter was first known as Theodora, Tsarina of the Bulgarians, and later as the nun Theophana—since 2022 recognised by the Romanian Orthodox Church as a saint. The Prince developed a new capital in the 1340s, at Curtea de Argeş, ‘the court on the Argeş’, the latter being one of the main tributaries that flows south from the Carpathians into the Danube. This town was located close to the Bran Pass, which connected Wallachia to Transylvania, and in particular to Romanian settlements north of the mountains and the significant trading city of Kronstadt (‘crown city’), founded by Hungarian kings and populated by Saxon/German colonists in the 12th and 13th centuries (today’s Braşov).

Basarab also built the Princely Church of St Nicholas, with its amazing painted interiors, and by the 1350s, in the reign of his son and successor, Nicolae Alexandru, had attracted the Metropolitan of the Orthodox Church to relocate his seat to the new capital. A monastery was built for him, which became the dynastic necropolis; re-founded as a cathedral in the early 16th century. The cathedral of Curtea de Argeş was re-appointed as a dynastic burial place, fully royal once Romania became an independent kingdom in the 19th century, and it remains so today.

Prince Nicolae Alexandru made a deal with the Hungarian king in 1354, recognising him as overlord and allowing him to send Catholic missions to Wallachia and to establish a Catholic diocese, to operate alongside the Orthodox churches and serve an increasing number of Saxon merchants settling south of the Carpathians and along the Danube Valley. Their presence would become a source of conflict later, as we shall see when we return to the story of Vlad the Impaler.

Successive voivodes, Vladislav I, Radu I, re-affirmed their loyalty to Hungarian kings, in exchange for a more secure title to the Romanian exclaves north of the Carpathians in Transylvania (Amlaş and Făgăraş). They married Hungarian noblewomen from Transylvania, but their daughters continued to make kinship ties with their other (Slavic) neighbours, resulting in another Bulgarian tsarina and a tsarina of the Serbs. Voivode Dan I tried to extend his rule south into Bulgaria but was defeated and killed in 1386.

His brother Mircea I was more successful, and earned the nickname ‘Mare’ (‘the Great’). He gained the territory at the mouth of the Danube on the Black Sea (Dobruja) in 1388, as well as the region bordering Serbia and Hungary, the Banat of Severin, in 1389. He strengthened the army and the Principality’s borders, brought in increased trade and developed a court culture to rival other princes. In 1394, Prince Mircea went to the aid of the Bulgarians now that the Ottoman Turks had arrived in the Balkans led by Sultan Bayezid. At first he repulsed the Ottoman attack in the valiant Battle of Rovine (another of these David vs Goliath moments celebrated in song and story), but was later chased out and replaced as voivode (or bey in Turkish) by Vlad I. Mircea joined the grand western crusade against the Turks in 1396, which culminated in their defeat at the Battle of Nicopolis, a severe blow to Christian power in the Balkans. But he reclaimed his throne in 1397, defeated the Turks again in 1400, and even intervened in Ottoman internal politics in the confused dynastic succession of 1403-06.

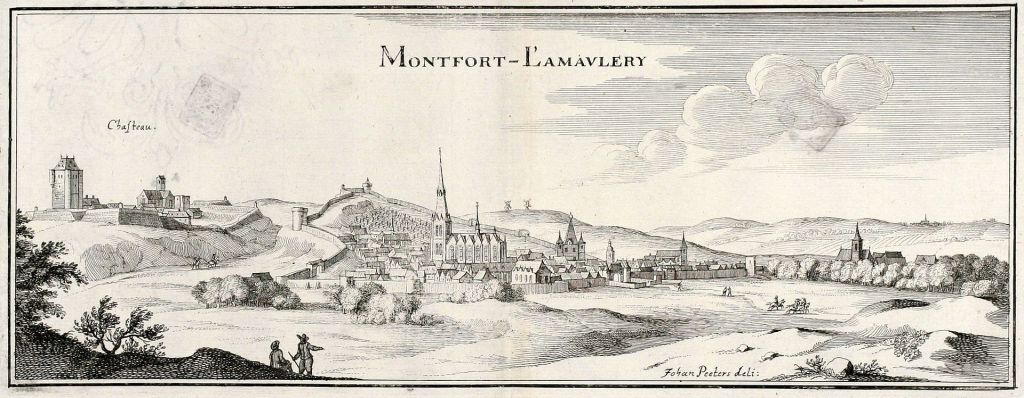

Prince Mircea also moved the capital of Wallachia once more, to the town of Târgoviște, to be a bit more central to the region. This town, which takes its name from the old Slavic word for ‘marketplace’ and had been settled by Saxon traders emigrating from Transylvania in the early 14th century. Mircea began the transfer of the princely court in about 1400, and fortified his residence—its grand tower, the Chindia Tower, was added later in the century by Vlad III.

Mircea the Great ruled peacefully until 1418 when he was succeeded by his son Mihail then his brother Radu II. Things start to get really messy again in the 1420s, as the dynasty split into two branches: the descendants of Mircea’s brother Dan I (the Dănești), and the family of Mircea’s illegitimate son, Vlad II ‘Dracul’ (the Drăculești). Different cousins competed for the throne with a variety of supporters, sometimes the local Romanian boyars, or nobles, and sometimes the Ottoman sultan, who first started demanding tribute in this period. Dan II re-asserted Wallachian independence, but was deposed and killed by invading Ottoman forces who placed his cousin, Alexandru I Aldea on the throne in 1432. Alexandru thus acknowledged the suzerainty of the Sultan and did formal homage to him in Adrianople.

When he died in 1436, Alexandru was succeeded by his brother, Vlad II. Vlad had been sent by his father to be raised at the court of Sigismund of Luxembourg, King of Hungary—initially as a hostage, and later as a guest and friend—and he was granted membership in the King’s new order of chivalry, the Order of the Dragon. When he returned to Wallachia at the head of a Hungarian army to take up his brother’s throne, he wore the badge of this order and thus was given the nickname ‘Dragon’ or ‘Dracul’. But Sigismund died in 1437, and, finding himself without a powerful patron, Vlad II turned to the Ottomans and agreed to do homage and pay a tribute. A few years later, in 1441, he changed his spots again and supported the invasion of Ottoman territory by the Hungarian prince of Transylvania (János Hunyadi), for which he was deposed and imprisoned by the Sultan. He was replaced by his cousin from the rival Dănești branch, Basarab II. But only a year later Vlad II was put back in charge of Wallachia, though he had to leave two of his younger sons, Vlad and Radu, in Ottoman hands as hostages, and agreed to send 500 Vlach boys to the Sultan’s court to be trained as Janissaries. Yet again, in the same year (1443), he turned against the Sultan and joined the crusade of western princes who invaded Bulgaria, and were badly defeated at Varna in November 1444. Vlad II Dracul made a separate peace with the Sultan in 1446, prompting his former ally Hunyadi to invade Wallachia in 1447; Vlad was captured and executed just outside the new capital at Târgoviște.

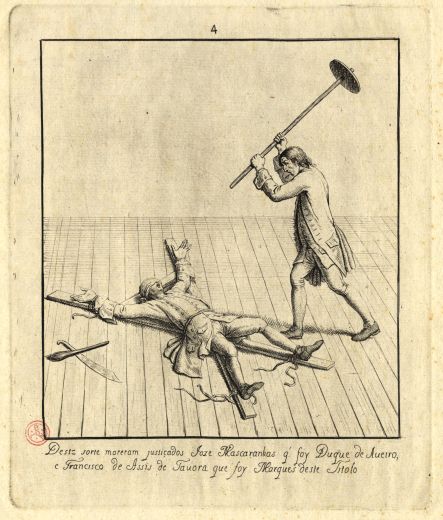

Vlad’s eldest son, Mircea II, had been a leader of his father’s troops in the Crusade of Varna; at the time of the invasion of 1447 by Hunyadi, he was captured by the frightened Wallachian boyars, who poked his eyes out and buried him alive. The horrors of this century were really starting to intensify. Again, a prince from the rival branch, Vladislav II, was named voivode, probably by Hunyadi, and ruled peaceably for several years. In 1455, however, he decided to bite the hand that fed him, and invaded Transylvania to lay claim to the Romanian settlements there and the key trading city of Kronstadt/Braşov; Hunyadi responded by supporting a coup by one of those two sons of Vlad II Dracul that had been left as Ottoman hostages back in the 1440s: Vlad III, the future Impaler. The cousins met for single combat in August 1456 and Vladislav was killed. Vlad Dracula (or Drakulya, ie, son of Dracul) soon revealed himself to be one of the most intensely ruthless rulers this part of the world had ever seen. In the face of ongoing opposition to his rule by Vladislav’s brother, Dan III, he staked his claim in the capital by rounding up Wallachian boyars and Saxon merchants who supported his rival, and impaled them on stakes all around the city. Dan led an invasion, with Hungarian support, in 1460, but was defeated in the Bran Pass, forced to dig his own grave, and beheaded. His supporters were impaled. Two years later, the Ottoman Sultan sent envoys, and (so the story goes) Vlad nailed their turbans to their heads, since they were ‘so attached’ to them that they wouldn’t remove them in his presence (a sign of honour). The Impaler reportedly created a ‘forest’ of 20,000 impaled bodies all around the city of Târgoviște to frighten Ottoman troops sent to avenge the ambassadors.

Die geschicht dracole waide

Already Vlad III was getting a reputation for extraordinary cruelty—real or exaggerated. Contemporary writers spread tales of his excesses across Europe. As the years went by, these stories grew: a German woodcut from 1499 shows ‘Dracule waide’ (voivode) dining casually amongst his impaled victims. As noted above, later Romanian nationalist historians would defend this reputation, seeing his severe acts as necessary in the goal of securing Wallachian autonomy in the face of two powerful neighbours and the internal self-interested treachery of the boyars. He is also seen by some as a crusader for the Orthodox Church.

Dracul does mean ‘devil’ (not ‘dragon’) in modern Romanian, but there is no indication that Vlad Țepeș (Romanian for ‘the Impaler’) was ever connected with local legends of vampirism, undead demons who survive by drinking human blood, until the era of the novel Dracula by Bram Stoker—and even here the link is only indirect. Stoker also used the name Nosferatu, thinking (probably incorrectly) that it was a Romanian term for ‘undead’.

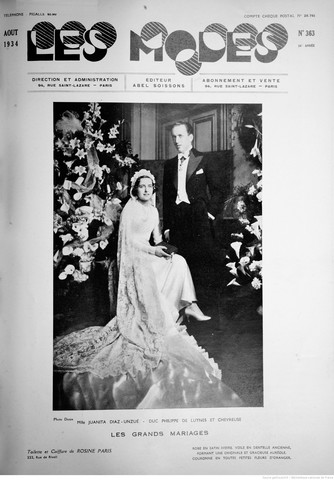

Bran Castle (perhaps due to the closeness of the name to Bram?) is today marketed as ‘Dracula’s Castle’ to foreign tourists, though it does not fit the description in Stoker’s novel very well, and really had very little connection to the historic Vlad the Impaler. It was built in the 1370s by the Saxon merchants of the town of Kronstadt (Braşov) and was maintained by them for centuries as the key defence of the mountain pass between Wallachia and Transylvania. Bran Castle became a royal residence in the 1920s, and was significantly renovated by the Romanian royal family; it was confiscated by the Communists in 1948, then restored to the family in 2006, in the person of Princess Ileana of Romania’s son, Archduke Dominic of Austria.

Dracula’s actual castle is high in the mountains of the upper Argeş valley: Poenari Castle, perched on a rocky spur. It had been the chief stronghold of the Basarab lords in the 13th and 14th centuries, and was rebuilt by Vlad III in the 1450s, supposedly using the slave labour of those same Wallachian boyars he so persecuted at the time of his accession to power.

Eventually, and unsurprisingly, these Wallachian boyars turned against him, and in 1462 compelled him to cross into Transylvania to seek help from the Hungarian king, Matthias Corvinus, who imprisoned him instead, in his castle at Visegrad for thirteen years. While there, some think he became a Catholic, and gradually earned Corvinus’ trust, and so he was again placed at the head of a Hungarian army to attack Ottoman troops first in Bosnia in 1476, then in Wallachia to reclaim his throne.

Back in 1462, the post of Wallachian voivode had at first been given, by the Ottomans, to Vlad’s younger brother, Radu III ‘the Handsome’ (‘Frumos’). Like Vlad, Radu had also been sent to the Ottoman court as a child hostage, but became more acclimated, and a very close friend to the Sultan’s son, Prince Mehmet. It is thought the teen boys became lovers, and Radu may have converted to Islam. Once Mehmet became Sultan (Mehmet II) in his own right in 1451, Radu was given a place of honour in his court (perhaps as a Janissary commander), and took part in the conquest of Constantinople (1453). Ten years later he was named voivode of Wallachia, promising to restore the privileges of the urban boyars and merchants in Târgoviște and Braşov that his brother had so brutally repressed. His reign was troubled, however, and he was deposed and restored several times, including by his son-in-law, Prince Stefan III of Moldavia, who was opposed to Radu’s loyalty to the Sultan. He died sometime in 1475 and was replaced as voivode by his cousin (from the Dan branch), Basarab III ‘Laiota’. It was this ruler Vlad the Impaler unseated in 1476; but by the end of the next year, the latter returned with Ottoman support, and drove Vlad from power once more. He was killed in battle in early 1477, probably on the outskirts of Bucharest.

(I’m sad I can’t find any contemporary images of Radu Dracula, but there’s a lot of sweet fan art depicting him and Mehmet… He was played by Serbian trans supermodel Andreja Pejić in a recent Turkish television drama)

Accounts vary about Vlad the Impaler’s death; one Italian diplomatic source says his body was cut into pieces and his head sent to Mehmet II and impaled (fittingly) on a high stake in Constantinople. One of his possible burial sites is Comana Monastery, to the south of Bucharest, which had been built by Prince Vlad in 1461. It was demolished and rebuilt in 1589, but the crypt remained, where archaeologists in the 1970s claimed to have found the headless body of a prince.

The city of Bucharest, or București, was at this time starting to be regarded as the new princely capital. A relatively new settlement, possibly taking its name from the Romanian word for ‘joy’ (bucurie), it was the preferred summer residence of Vlad III who built what later became known as the Curtea Veche (‘Old Court’) sometime before 1460. The palace was extended and renovated in the late 17th century, but was replaced with a ‘New Court’ in 1775. A church was added to the princely complex in the mid-16th century, with tombs associated with the Basaraba dynasty in this period. București and Târgoviște alternated as Wallachian capitals, with the former predominating in periods of more pro-Ottoman relations due to its proximity, then formally becoming the sole capital towards the end of the 17th century.

The successors of Vlad III came and went in quick succession, with the two branches of the family continuing to vie for power with or without Ottoman support. Basarab IV, from the Dănești branch, was in a way the inheritor of The Impaler’s mantle, known as Țepeluș, ‘the Little Impaler’ (how sweet!). He ruled as voivode twice in the late 1470s-80s and sided with the Ottomans in a great clash with the Hungarians in 1479. He was killed in 1482, either in battle or in a boyar conspiracy. His successor was again from the Drăculești branch, an illegitimate half-brother of Vlad III, known as Vlad IV ‘the Monk’, put on the throne by the neighbouring Prince of Moldavia, but soon forced to accept Ottoman suzerainty once more. Strangely, he seems to have died in his bed, of old age, in 1495, and even was succeeded peacefully by his own son, Radu IV ‘the Great’, who ruled for another decade, and also seems to have died peacefully. His epithet ‘the Great’ refers not to any great victories, but to his position as a great patron of the arts and protector of the Orthodox Church, not just in Wallachia, but across the Orthodox world.

Radu the Great was succeeded by his cousin, Vlad the Impaler’s son Mihnea, who, like his father, pressed for Wallachian independence but was challenged by boyars who enjoyed the favour of the Ottoman court and the profits to be gained from being part of that vast eastern empire (which makes sense to a non-nationalist historian like me). Mihnea was given the nickname ‘the Wicked’ by his enemies, including one of these boyar families, the Craioveşti, who would later take on the role of voivode themselves. Prince Mihnea was run out after only a year, followed only a few months later by his son, Mircea III Dracul.

He was succeeded by yet another cousin, Vlad V ‘the Younger’ (a son of Vlad ‘the Monk’), in 1510, placed on the throne by the increasingly powerful Craioveşti family with Ottoman support. But a year later, he switched allegiances and swore fealty to the King of Hungary—this of course led to his deposition the following year by the same boyars and Ottoman soldiers, and he was decapitated. A different kind of ruler succeeded in 1512: Neagoe, who claimed to be from the Dănești line, a son of Basarab IV, and not his mother’s husband, one of the Craioveşti boyars. He was voivode for nearly a decade, and proved to be a capable administrator and a skilled diplomat, desiring to act as mediator between eastern and western branches of Christianity. He sponsored the building of Curtea de Argeş Monastery (1517) and the Metropolitan Cathedral in Târgoviște. He was also a scholar, and published a Romanian translation of the Gospels in 1512. He was canonised by the Orthodox Church in 2008.

The sixteenth century continued in much the same fashion: princes named either Vlad or Radu had relatively short reigns, either with support or in defiance of the Ottomans. The principality was basically independent but paid heavy tributes to the Sultan. Prince Patrascu ‘the Good’ (‘Bun’) ruled in the 1550s and helped the Ottomans restore John Sigismund Zápolya as Prince of Transylvania in defiance of the Habsburgs. His cousin Alexandru II was raised at the Turkish court and put on the throne in the 1570s, but like his great-grandfather Vlad the Impaler, he soon became known for his cruelty and was deposed and murdered by his boyars. His son followed in the 1580s, Mihnea II ‘Turcitul’ (‘turned Turk’) who earned his nickname late in life by converting to Islam (having been thrown out of Wallachia in 1591), and accepting an appointment as sanjak (governor) of Nikopolis in Bulgaria (as Mehmet Bey).

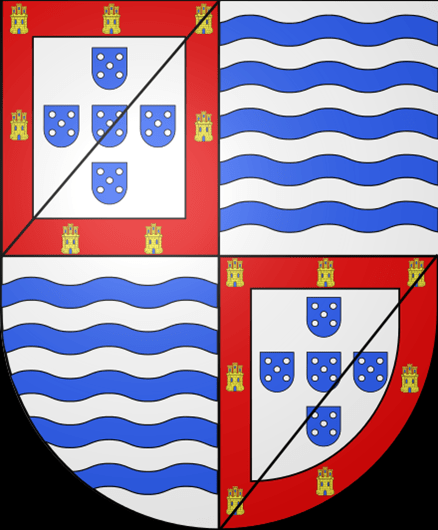

(this still features as one of the quarters of the modern Romanian seal)

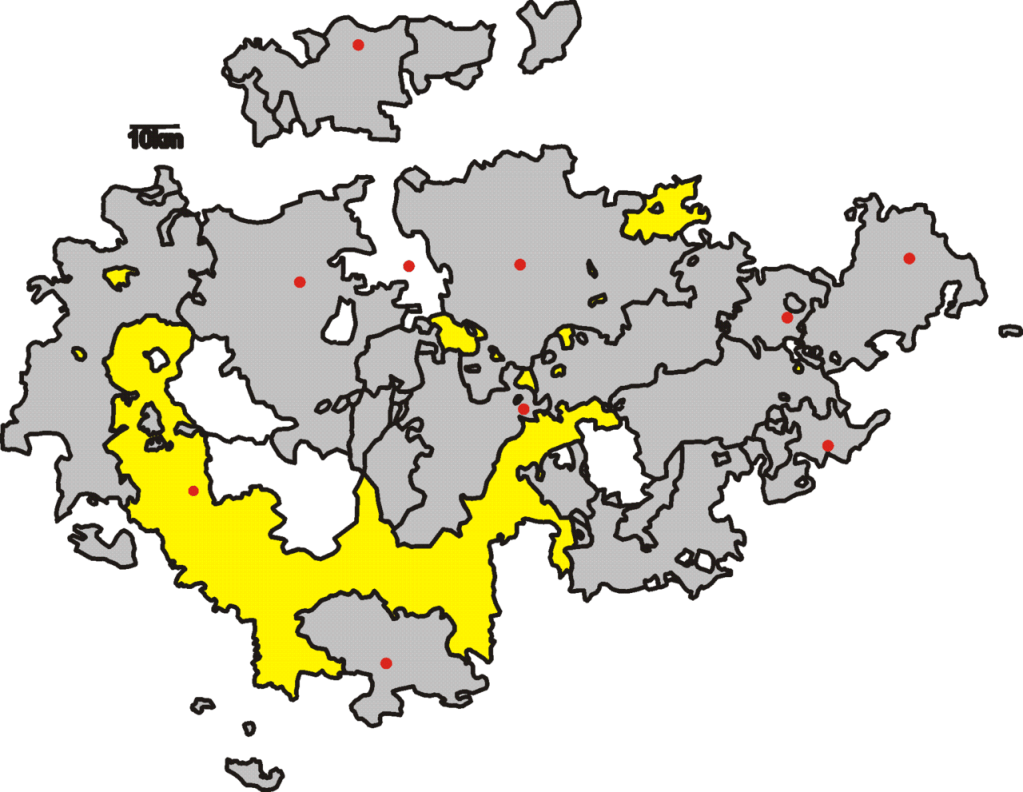

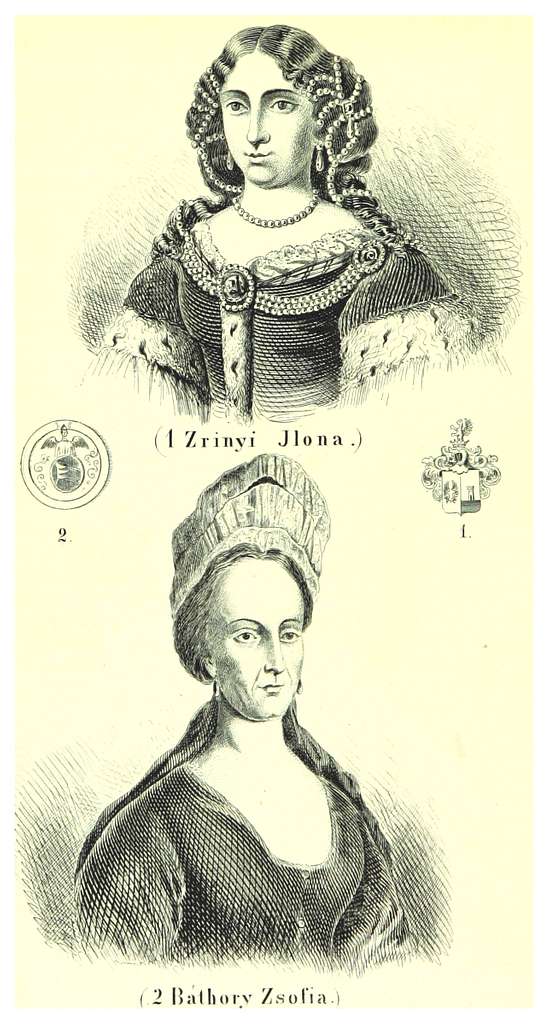

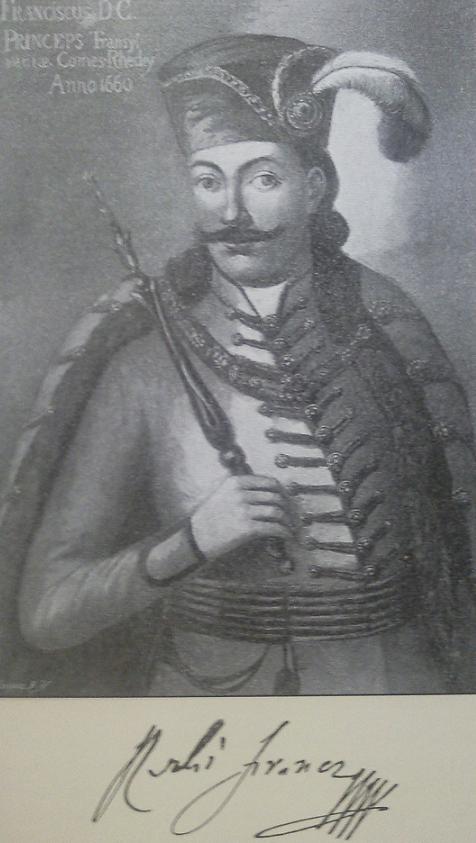

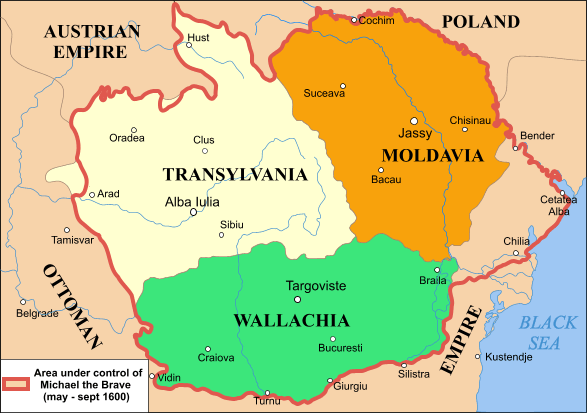

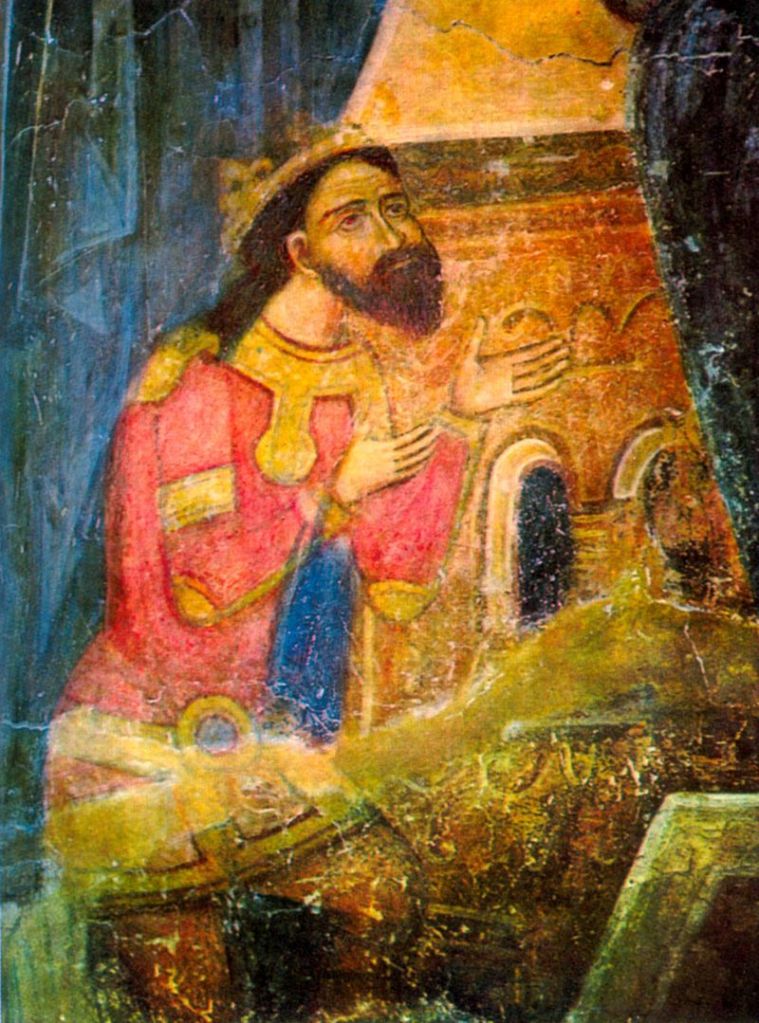

By the mid-1590s, the voivode of Wallachia was no longer appointed exclusively from within the Basarab family, with other local families filling the post. But the dynasty had one more burst of glory in the person of Michael ‘the Brave’ (or Mihail ‘Viteazul’), who not only restored Wallachia’s autonomy, but briefly united all three Romanian principalities for the first time in their history. He is thus seen as one of the major national heroes of Romania and a symbol of unity. He is described as a son of Patrascu the Good, but some claimed he only assumed that kinship to hide his more plebeian origins. Michael was first a regional governor in Ottoman service, then invested as Voivode of Wallachia by the Sultan, Murad III, in 1593. In 1595, he renounced this loyalty, declared Wallachian independence, and defeated a much larger Ottoman army at Călugăreni, near the Danube, allied with Emperor Rudolf II of Austria (as King of Hungary) and Sigismund Báthory, the Prince of Transylvania. He also defeated the Turks at an important crossing of the river, near Giurgiu. Peace was brokered with the Ottomans in June 1599, and Michael (encouraged by Rudolf) turned on and defeated Sigismund’s successor, András Báthory in October. Rudolf named him governor, not prince, of Transylvania, but he was de facto its ruler, following a triumphal entry into its capital of Alba Julia. In the spring of 1600, Michael travelled east to Moldavia and deposed his rival from the Movilă family, and named himself prince there as well.

This unity did not last long, and by the end of 1600, the Transylvanian nobles, unnerved by Michael’s ambitions, threw him out. He was then defeated in Moldavia by troops sent by the king of Poland, and was even chased out of most of Wallachia. Prince Michael went to Prague to the court of Rudolf II to plead for Imperial support; eventually given Habsburg funds and supplies, he re-took Wallachia, then Moldavia, but when he tried to retake Transylvania in 1601, Rudolf thought it was too far and sent orders for the Vlach prince to be murdered. Nice.

Though it was short, under Michael the Brave’s reign, boyar power in Wallachia increased and serf freedoms were curtailed—as a result voivoides in the 17th century had much less autonomy, and were made and unmade by Ottoman sultans from multiple boyar families, never allowing any one to gain too much power or stability. Yet Michael’s memory remains solid in Romania, as responsible for strengthening the authority of the Romanian Orthodox Church in all three principalities, and awakening (it is claimed) some form of early Romanian nationalism. Centuries later, a new royal order of chivalry was created by King Ferdinand of Romania during World War I: the Order of Michael the Brave.

Michael’s immediate successor was Radu IX Mihnea, who ruled on and off in both Wallachia and Moldavia—at one point trying to control both by installing himself in the Moldavian capital of Iaşi (Jassy), and his son Alexandru in Bucharest. This Radu was a reformer, of government and of foreign policy, trying to align with the leading mercantile power in the east, Venice. His son Alexandru was nicknamed ‘Coconul’ (‘the Cocoon’) because he began his reign at such a young age. He ruled at times both Wallachia and Moldavia in the 1620s, sometimes paying large sums to obtain his appointment, but never proving to be that effective as a ruler. He was removed from power in 1630 and died in Istanbul in 1632. He was the last of the direct descendants of Vlad Țepeș, the last of the House of the Dragon.

There were others who claimed affiliation with the Basarab family in the 17th century. Many of these were in fact from the Craioveşti family (or the related Brâncovenești family), as above, including Radu Şerban, one of the better rulers of the period (1602-11), preserving Wallachian independence and reforming the government. Matei Basarab, with one of the longest reigns (1632-54), adopted this dynastic name to associate himself more securely with Wallachian identity, in competition with the increasing number of outsiders, especially Greeks, being appointed by the Ottomans as voivodes. He was an enlightened ruler, introducing the printing press, codifying the laws and founding schools. He also allied with the Prince of Transylvania, George II Rákóczi, with an aim to create an independent state, but this idea was crushed in the next reign (Constantin II, son of Radu Şerban) by the troops of Sultan Mehmet IV in 1658. The Sultan therefore appointed Mihnea III Radu, who claimed to be a son of Radu IX, but many said he was a Greek money lender from Constantinople and had agreed to pay the Sultan a rather large sum for the privilege of serving as voivode—but only for a year.

After this point, appointments to the post of voivode were much more clearly servants of the Ottoman court, often noblemen from Greek families known as Phanariots. These families, notably Cantacuzenos and Mavrocordatos, will be the topic of a future blog post on their own. Wallachian autonomy continued to decline, and after 1716, the Ottomans no longer even pretended the post of voivode was an elective position, depriving the local boyars of even the pretence of self-rule. The idea of a united state of the two Romanian principalities of Wallachia and Moldavia was revived in the 1820s, in the wake of the Greek War of Independence, and although they were formally tied together in 1859, Romania remained nominally a vassal state of the Ottoman Empire until formally proclaiming its sovereignty in 1877 (with Transylvania remaining a part of Hungary until after the First World War). Twenty years later Bram Stoker would popularise the name Dracula and its association with Transylvania and the Carpathian Mountains, but it was not until the cinematic versions of the story were produced that people began to associate the Prince of Darkness with Vlad III, voivode of Wallachia.

(images Wikimedia Commons)

Basarab Dynasty, simplified