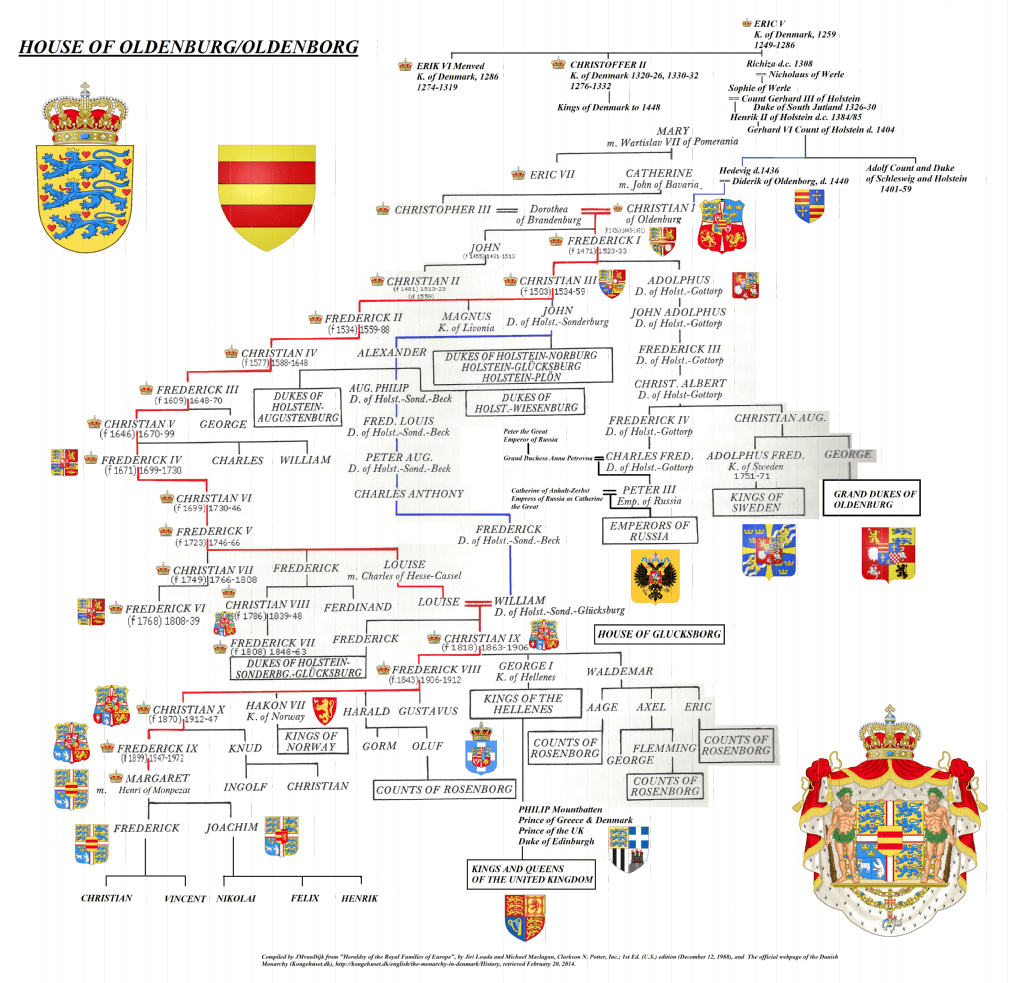

The name Windsor was chosen to represent the royal family of the United Kingdom in 1917, taken, quite rightly, from the castle that had been at the centre of royal operations in England since the 11th century. But if we go back to an older way of giving names to royal dynasties, the name traditionally adheres to the male lineage, so when the current British monarch passes away, by this form of reckoning, the House of Saxe-Coburg will give way to the House of Oldenburg. “But I thought Prince Philip was Greek?” I hear you say. Greece was also once governed by the House of Oldenburg. And so is the current Kingdom of Denmark. And Norway. Oldenburgs once supplied monarchs to thrones of Russia and Sweden as well.

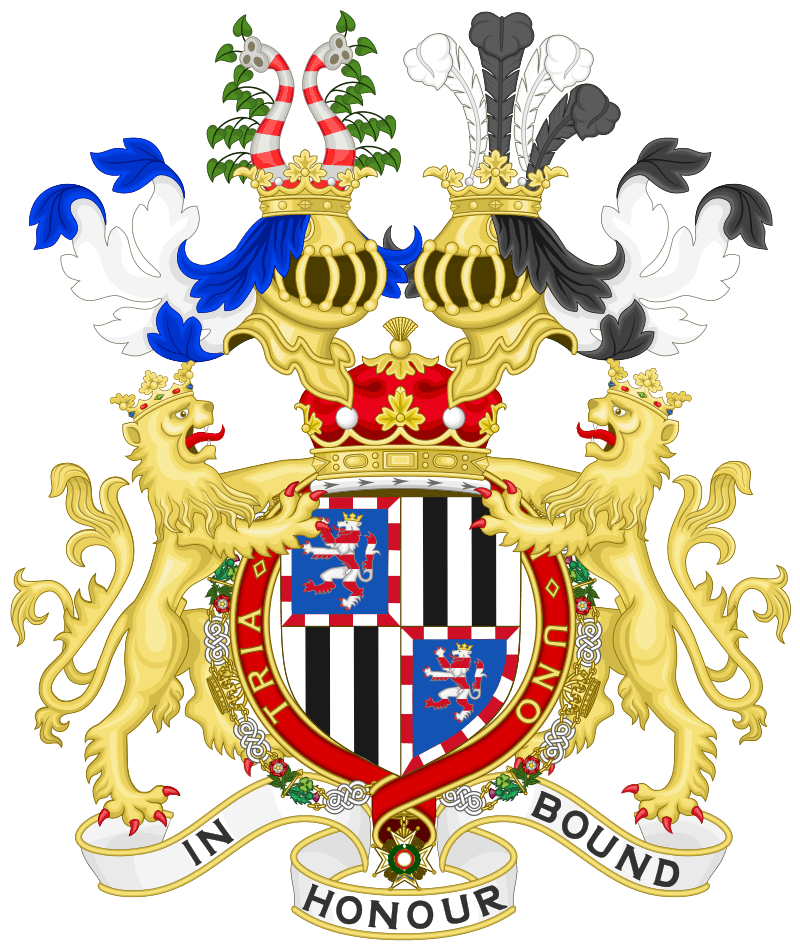

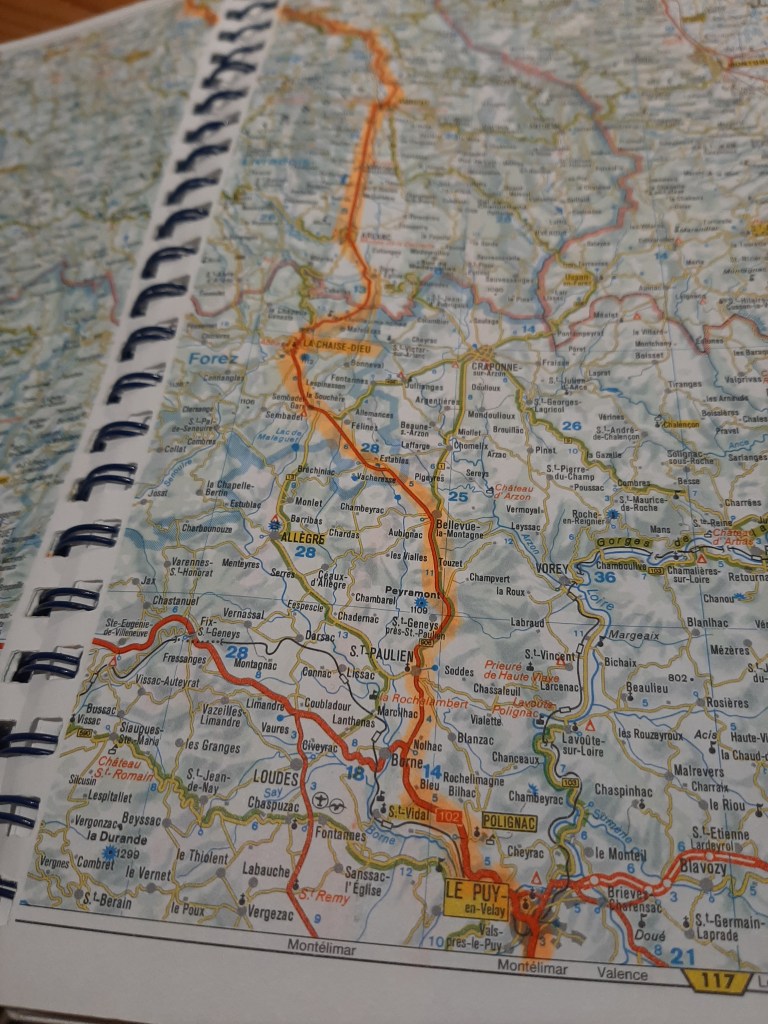

If most royal dynasties take their names from the castle from which they originated, where is Oldenburg? This post will look at the origins and extremely successful spread of the House of Oldenburg, the future royal house for Great Britain. Connections will be made with the royal houses of Denmark, Greece, etc, but in keeping with the theme of this website, I will stick to dukes and princes, and look at the various castles and palaces built in the Grand Duchy of Oldenburg and the duchies of Schleswig and Holstein in the fascinating border region between Germany and Denmark. As people who enjoy their royal trivia love to tell you, the “real” surname of the Prince of Wales should be Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg. That’s a mouthful.

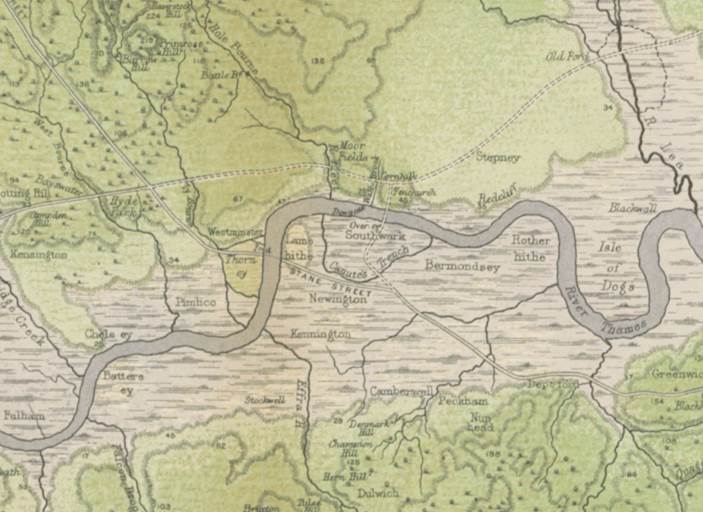

In the late 11th century—the same time Windsor Castle was being built by the Normans in England—a Saxon count named Egilmar established himself at a strategic crossing of the river Hunte on the very flat north German plain to the west of the city of Bremen. Here he built a castle called Oldenburg. He married a noblewoman from the other side of the massive Elbe estuary, Dithmarschen, establishing a link between these two low-lying and rather marshy territories that would endure for centuries, and would continually entwine Denmark in north German politics. This is the same area from which the Angles and the Saxons emigrated across the North Sea to Britannia in the 5th century, so perhaps it is fitting that the Oldenburg name has finally arrived on these island shores.

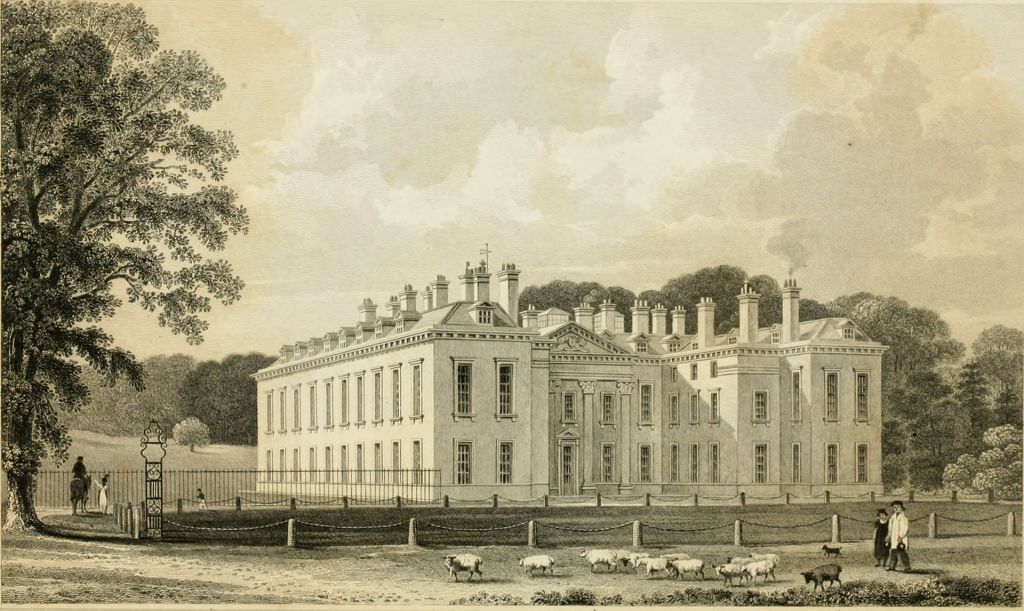

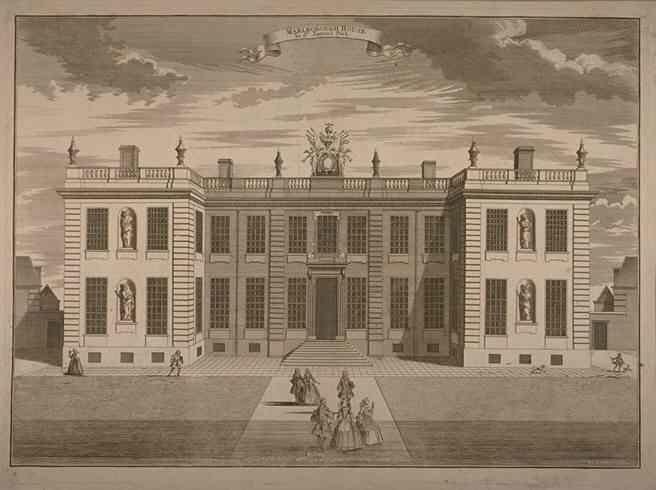

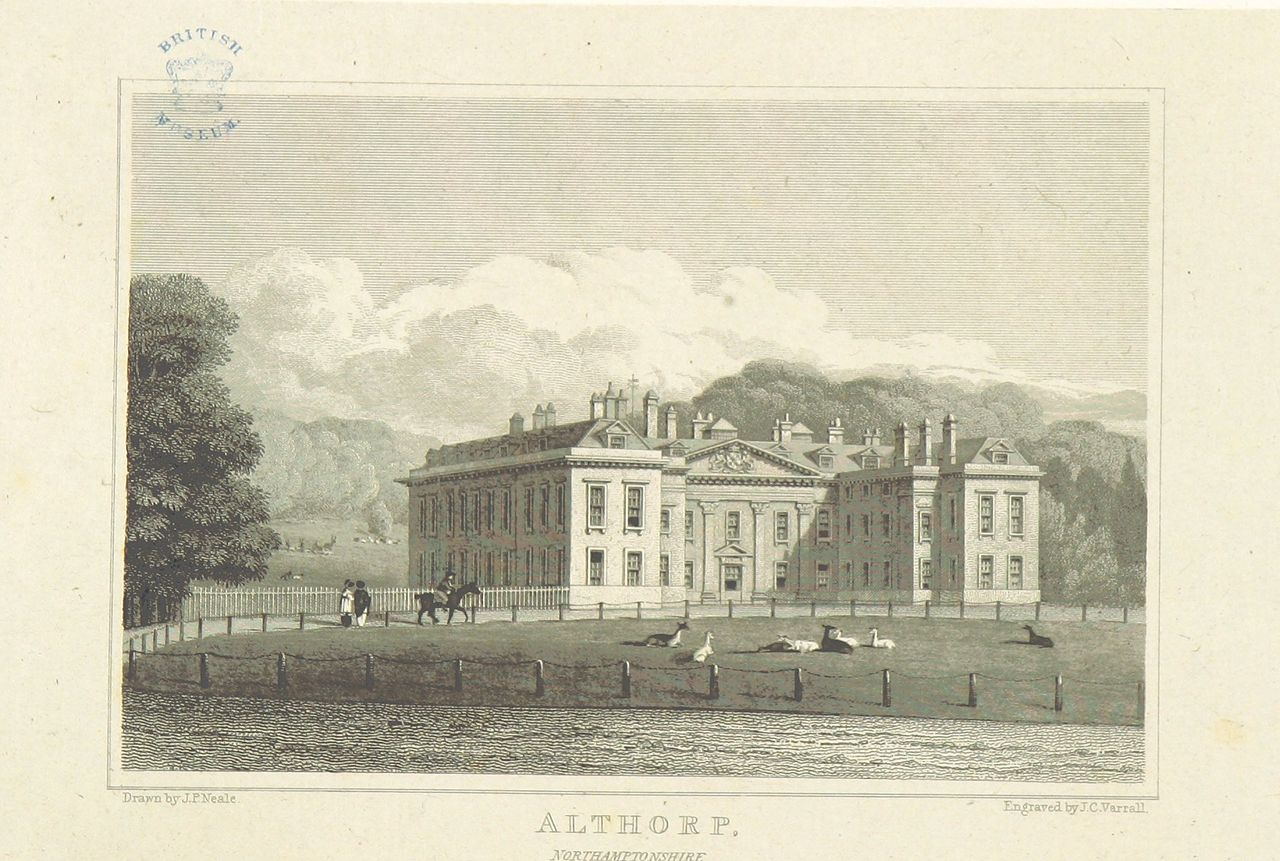

Oldenburg Castle was the seat of a long line of counts—often using the name Christian—who were subsidiary to the dukes of Saxony, then autonomous princes of the Holy Roman Empire until the extinction of the ruling line in 1667. The castle seen today in the city of Oldenburg was rebuilt in the Renaissance style in the early 17th century, and still dominates the centre of town with its bright yellow towers. After 1667, the county was ruled by Denmark and the castle became the seat of a Danish governor, until a junior branch was re-established as dukes (1776), then grand dukes (1815) of Oldenburg, and the Castle was restyled once more in a neoclassical style. Today it is a museum of art and culture, together with the nearby Prinzenpalais, built in the 1820s to become the official residence of the grand dukes, and the Elisabeth-Anna-Palais, the family’s residence from the 1890s until their abdication in 1918.

A few miles north of the city, the counts of Oldenburg maintained a close relationship with the abbey of Rastede, and following the Reformation, transformed its buildings into a hunting lodge, then a summer residence in the 1640s. The newly established dukes of Oldenburg of the 1780s refashioned this too along neoclassical lines, and added the then very fashionable English gardens. Schloss Rastede remains the residence of the ducal family today, and they also still own Eutin Castle, one of the most significant castles in Holstein, a former seat of the prince-bishops of Lübeck, transformed into the country residence of the grand dukes of Oldenburg in the 19th century, and acting as a point of contact with their Danish and Russian relatives.

The grand dukes of Oldenburg were never a hugely influential dynasty in 19th-century Germany. But they maintained a high profile as close relations of the royal families of Russia, Denmark and Sweden, and regularly provided consorts to these and other European monarchies. The first to make his mark as grand duke was Augustus, who ruled from 1829 to 1853, and endeavoured to turn this corner of Germany from a mere backwater ruled for a century by Danish governors into a centre for modern agriculture, trade and the arts—though like many of his peers, he resisted granting his state a constitution, still fearing the disorders of popular movements had had witnessed as a young man. Conservatives like him adhered to the older idea from the Enlightenment that an educated benevolent prince was the best way to bring peace and prosperity to the people. Grand Duke Augustus established an efficient if autocratic government and sponsored a theatre, an orchestra and a teaching college founded by his father (the future Oldenburg University).

This form of paternalism worked for a small population (about 800,000 people), and was continued by Augustus’ successor, Grand Duke Peter II (r. 1853-1900), but it was increasingly out of step with liberalisation movements spreading across Germany. Peter proposed a constitution for a North German Confederation in the 1860s which retained most of the power for the old ruling princes of the now quite defunct Holy Roman Empire, an idea which was quickly discounted. At home, he increasingly restricted the role of the local parliament, and despite carefully planned reforms from above, his state stagnated.

The last reigning Grand Duke, Friedrich August, maintained this hereditary conservatism, but was also very popular, in particular due to his achievements in continuing to develop trade centres for Oldenburg, notably in its canals and ports along the Weser River. Closely associated by marriage to the Imperial family in Berlin, he tried to influence German politics during World War I with his ‘annexationist’ policies, advocating the expansion of the German Empire in Belgium and northern France. He abdicated with the rest of the German monarchs in November 1918. His son, Nikolaus, was head of the family from 1931 to 1970, retreated to a low profile for himself, tending to the family’s agricultural interests at Rastede, and to a more local, small-scale image for the dynasty (resuming the title ‘duke’ rather than ‘grand duke’ for example). Nikolaus’s son was given one of the very traditional dynastic names, Anton Günther, and he remained active in local forestry and agriculture in Holstein and Lower Saxony until his death in 2014, when the headship of the family passed to his son, Christian (b. 1955). One of his cousins, Eilike, brought the family back into the news of the fervent royal watchers in 1997 when she married Archduke Georg of Austria, Prince of Hungary, second son of the heir to the Austrian and Hungarian thrones, in St Stephen’s Basilica in Budapest—which, as it happens, was my one and only genuine moment of royal geekery since I travelled to Budapest to witness it.

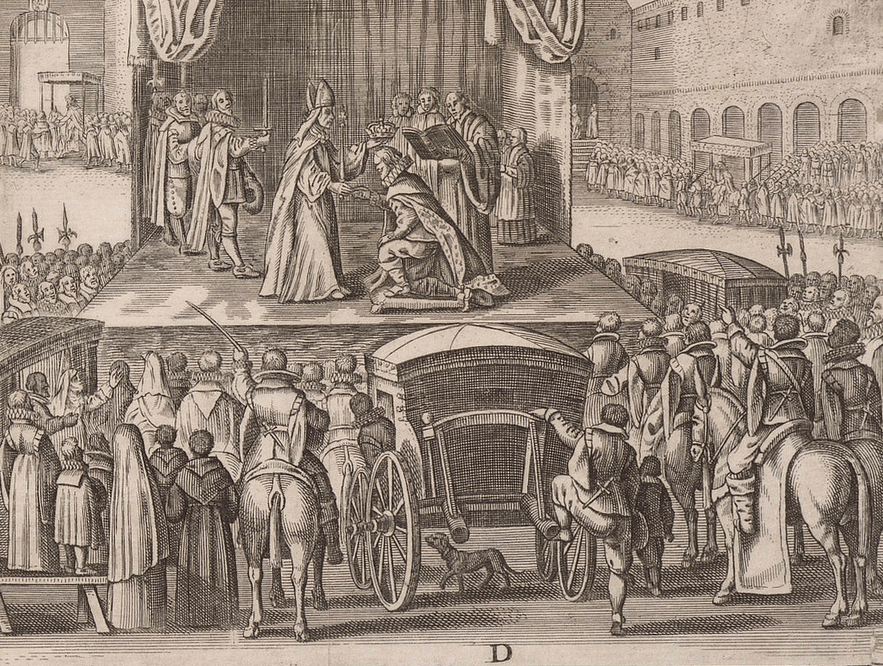

It is royal marriages at the very top levels like this, that have continued to bring the House of Oldenburg to prominence, over and over. The most recent, you might say, being Prince Philip of Greece’s wedding to Princess Elizabeth of Great Britain in 1947, but it would certainly also include Philip’s cousin Sophia’s wedding to Juan Carlos of Spain in 1962.The original marriage that propelled the dynasty into the premier rank was that of Christian VII, Count of Oldenburg, to the Dowager Queen of Denmark, Norway and Sweden, Dorothea of Brandenburg, in 1449, as part of the agreement that would bring Christian onto the Danish throne.

The main reason for the council of the realm of Denmark to choose Christian for their next king after the death of King Christopher in 1448, was that he was the nephew and heir of Denmark’s most powerful feudal lord, Adolf, Duke of Schleswig and Count of Holstein. These two territories formed the important bridge—politically, economically, culturally—between the Kingdom of Denmark and the Holy Roman Empire (in fact, Schleswig was in one, and Holstein in the other), so the Danish elites wanted to keep them secure and more fully under Danish influence. They also wanted to try to preserve the union of the three Scandinavian kingdoms—Denmark, Norway, Sweden—which was indeed rebuilt once again by 1457 by King Christian. The royal house of Oldenburg would rule over Denmark and Norway (losing Sweden in the 1520s) until 1814, then Denmark alone, up to the present day. There was a glitch in the dynastic succession in the 1860s, when the senior line died out, and the throne passed to a junior branch, Glücksburg (about whom below), which is today headed by Queen Margarethe II. With her death, the family name might be said by purists to change to the House of Laborde de Monpezat, but in reality it will remain Oldenburg.

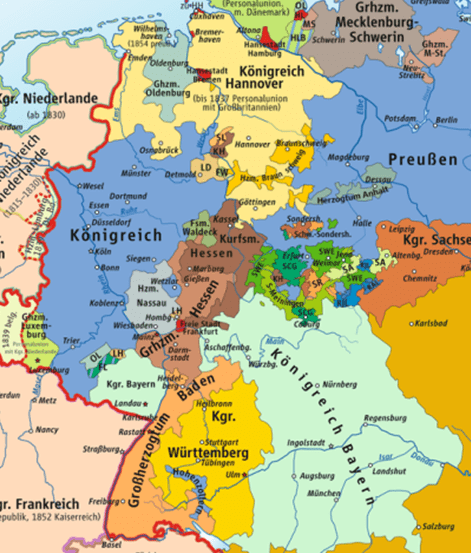

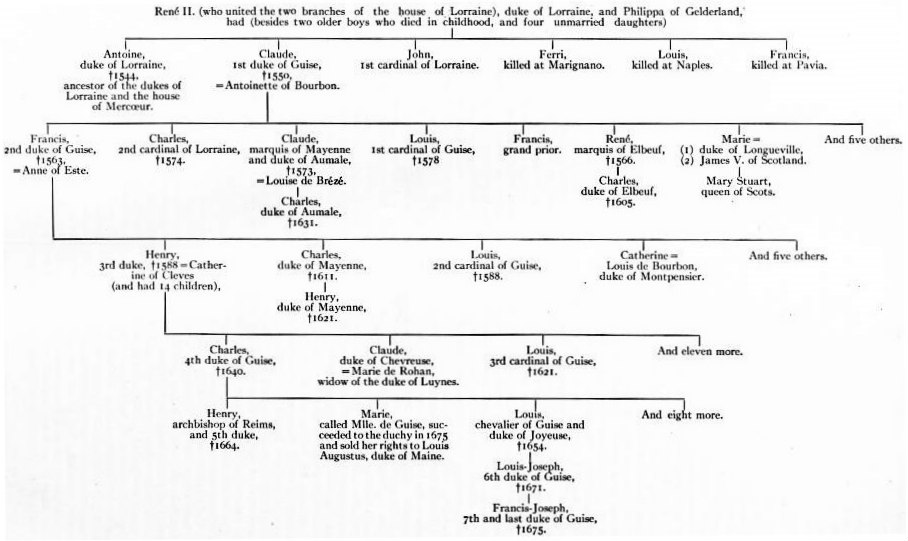

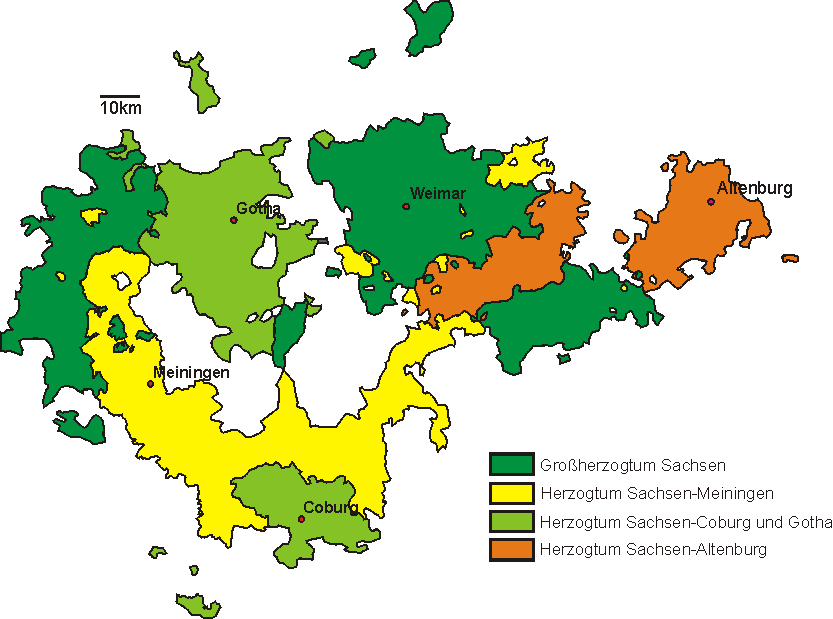

It is with the sons of King Christian I that begins the incredibly complex and convoluted story of the duchies of Schleswig and Holstein (the latter raised to the status of a duchy as well in 1474). I will only touch on some highlights here, or we’d be here all night, and will focus on the pathway that led to the emergence of the branch of Glücksburg as the leading branch of the family by the mid-nineteenth century.

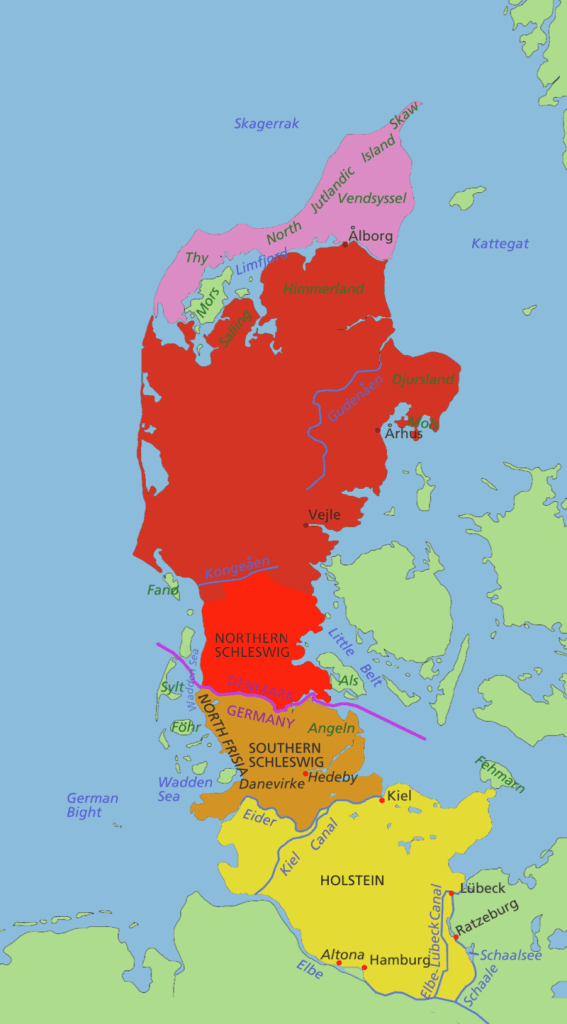

Schleswig takes its name from a town on the Schlei, an inlet of the Baltic Sea, plus the Danish vik or ‘bay’. It was a southern stronghold of Viking and Danish kings, but became a ‘march’ or frontier of the Empire in the early 10th century and was gradually colonised by Germans, mostly Saxons from the county of Holstein—which was itself established as a stronghold against Slavs on the Baltic coast, with a new bishopric set up at Lübeck to Christianise them. The Eider River was the boundary between Schleswig and Holstein, and by the 1230s the former was firmly Danish territory, and was created a duchy to be given as an apanage to younger sons of the royal house. Holstein, taking its name from a local tribe of ‘wood dwellers’ (Holcetae), was ruled by a line of independent counts from about 1100 from the House of Schauenburg (later spelled Schaumburg), originally from Westphalia. As with most German dynasties, they soon split their patrimony into the sub-fiefs of Itzehoe, Plön, Pinneburg, Rendsburg. The latter of these rose to prominence in the 14th century as regents or rulers of Schleswig, and even at times dominating the affairs of Denmark itself. From 1375, Schleswig and Holstein were ruled together—though one still a fief of Denmark, and the other a fief of the Empire—until they passed together in 1460 to the House of Oldenburg. All of the other branches of the House of Holstein had died out by then, with the exception of Pinneburg (with territory just outside Hamburg), which continued for another two centuries, though with little influence.

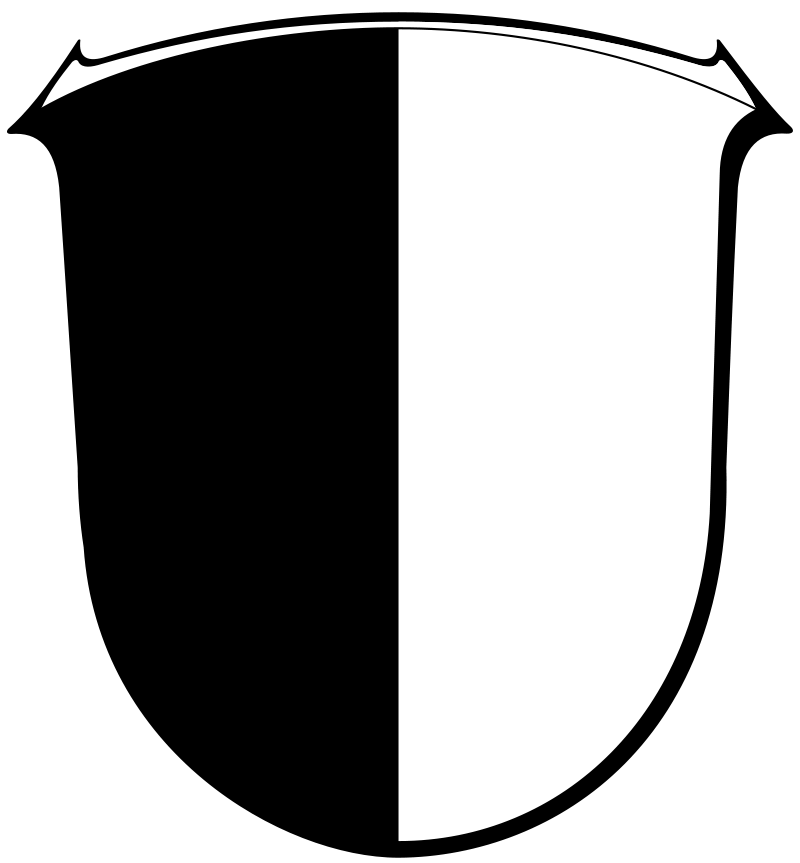

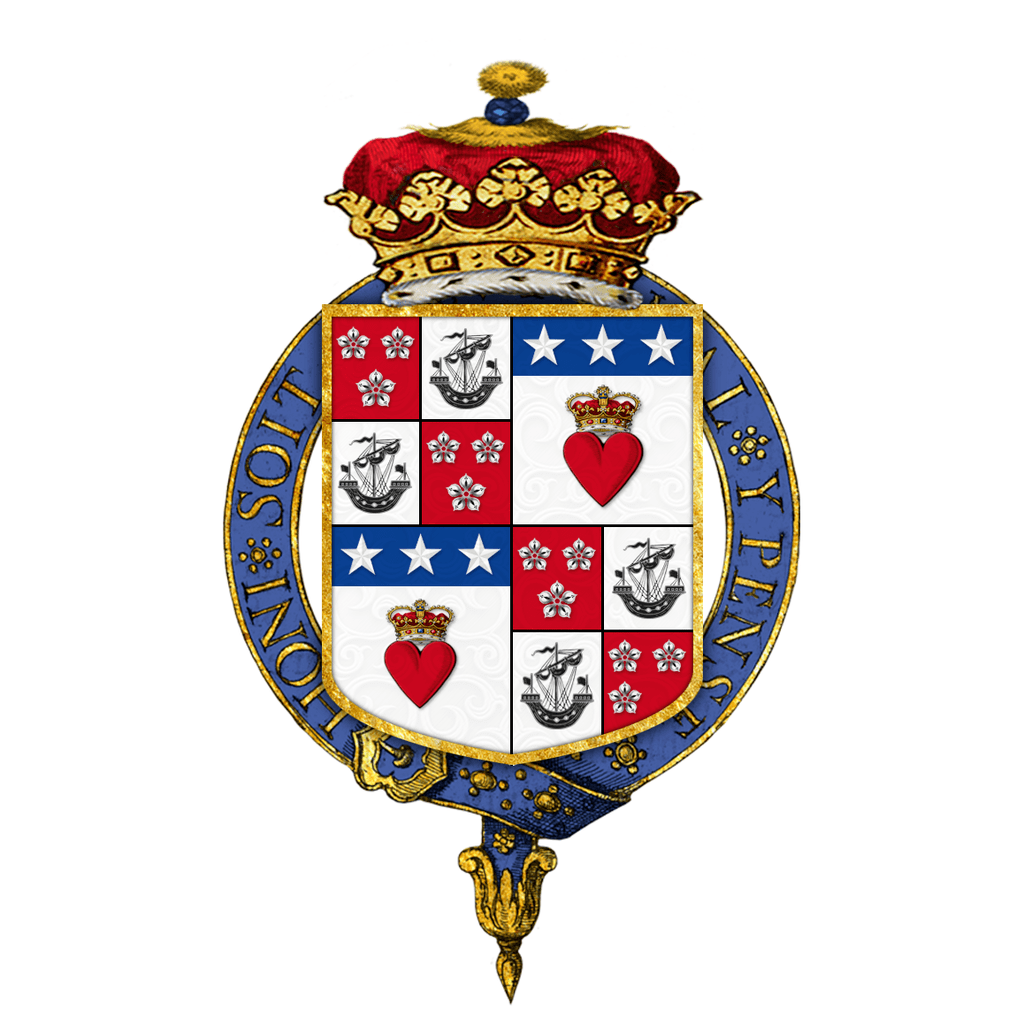

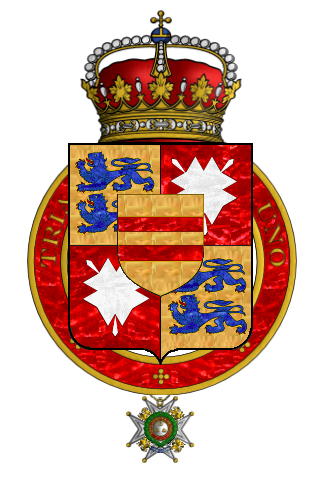

The coats of arms of these two territories are distinctive: Schleswig bears the two blue lions on gold, while Holstein is represented by a stylised nettle leaf, fairly unique in the world of heraldry.

Two important laws had been passed in these centuries of strife—both of which would come back to haunt Dano-German diplomacy in the nineteenth century: in 1325, the ‘Constitutio Valdemariana’ stipulated that the thrones of Schleswig and Denmark should never be held by the same person; and in 1460, the Treaty of Ribe ordered that Schleswig and Holstein must always be united. King Christian I of Oldenburg violated the first of these by uniting them all together under his personal rule. His sons ruled them jointly, and it wasn’t until 1544 that a formal separation of sorts was made, and a younger son of King Fredrick I, Adolf, was named duke of Schleswig and Holstein with his base at Gottorp.

Even after this date, legally the duchies remained indivisibly ruled, as a ‘condominium’ between the kings of Denmark and the cadet branches, who all bore the title ‘duke of Schleswig and Holstein’. By the 17th century, the two co-ruling branches were therefore known as duke of Schleswig-Holstein in Gottorp, and the duke of Schleswig-Holstein in Glückstadt (for the Danish Crown), the latter being a new town and harbour founded on the Elbe (in southernmost Holstein) by the Danish kings in an attempt to compete with the trade juggernaut of the independent City of Hamburg, a few miles upstream.

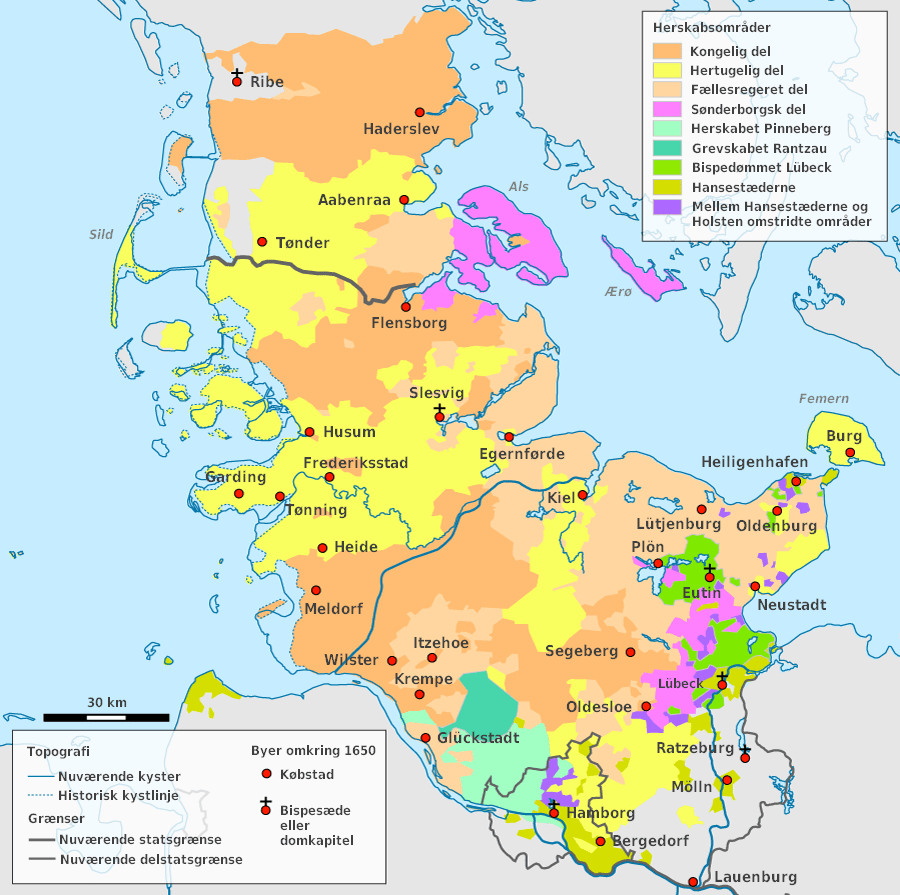

by the dukes in orange, ruled jointly in lighter orange, and lands given to the Sonderburg line in pink

(the other colours are for two independent counties and the bishopric of Lubeck)

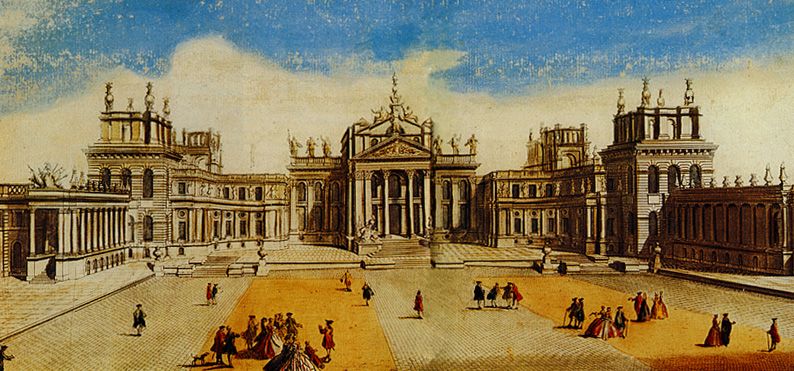

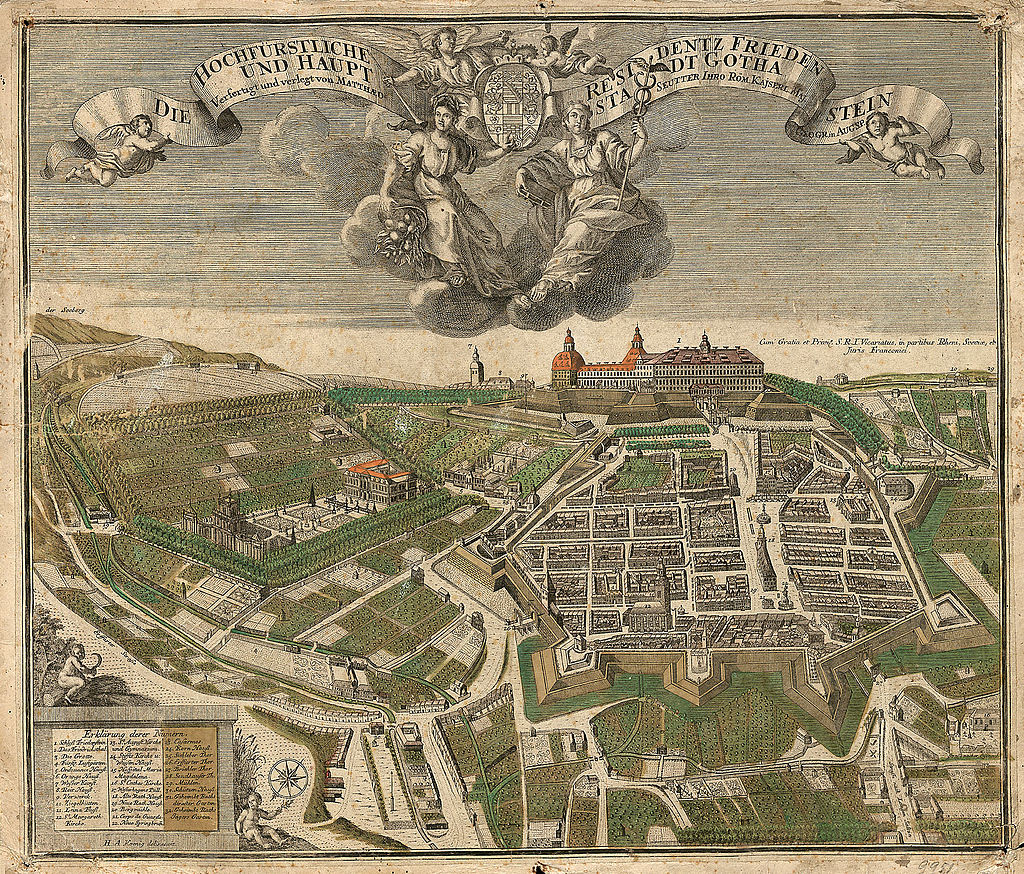

The branch of Holstein-Gottorp took over the old capital of Holstein, with its island stronghold built in the 12th century, the Castle of Gottorp (Gottorf in German). It was rebuilt as a princely residence in the mid-16th century, and rebuilt again in its current form in about 1700 by the famous Swedish architect Nicodemus Tessin the Younger.

But Duke Friedrich IV, having married the King of Sweden’s sister, supported Sweden against Denmark in the Great Northern War, and the castle was taken away from them by the treaty that ended the war in 1720, along with a large chunk of Holstein and their portion of Schleswig (which was therefore now fully reunited under the Danish Crown). Gottorp Castle became a barracks for the next three centuries, and is now part of the state museum system for Schleswig-Holstein. The ducal family moved to their secondary residence, the Castle of Kiel, an old fortress that had often been used as a dowager residence for its widows. In the 19th century, Kiel Castle would become the seat of the Holstein government, then residence of its Prussian governors. As a major centre for German naval power, the town of Kiel and its castle were almost completely destroyed in the Second World War.

Feeling they needed to bolster their family’s power with foreign marriages, the duke of Holstein-Gottorp who had lost much of his patrimony, Karl Friedrich, married Anna Petrovna, the daughter of Peter the Great. His first cousin and heir, Karl August, was set to marry the other daughter, Elizabeth, but he died. Both had ambitions to succeed their maternal uncle on the throne of Sweden, which ultimately Karl August’s younger brother, Adolph Friedrich, did, in 1751. By this point, Anna Petrovna’s son, Karl Peter, was established in St. Petersburg as the future Tsar of Russia, having been brought there by Elizabeth Petrovna, now Empress, as a teenager and married off to his cousin, the daughter of yet another Holsteiner, Johanna Elisabeth, Princess of Anhalt-Zerbst. This bride would of course become Catherine the Great, and Peter III and Catherine’s story is well known. Through them the House of Oldenburg would rule Russia—though under the name Romanov—until the Revolution of 1917. Meanwhile, the King of Sweden had sons and the House of Oldenburg would rule in Stockholm—under the name Vasa—until they were replaced in 1818 by the Bernadottes who reign today.

Back in Denmark, the idea of a conjoined Russia-Gottorp throne was pretty uncomfortable. So in 1773, a family pact was made, whereby Denmark and Russia exchanged the remaining Holstein lands that remained outside of Crown control for the old County of Oldenburg. Russia then ceded Oldenburg to a junior Holstein cousin, and the new house of Oldenburg, as detailed above, was born. Russia got a firm ally in Denmark out of the deal—to help control its chief rival in the Baltic, Sweden—and Denmark finally got a unified rule over the duchies of Schleswig and Holstein. Everybody is happy.

After the destruction of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806, Holstein joined the Germanic Confederation in 1815, and its ruler, the King of Denmark was happy to interfere in German politics. That old law about forever keeping Schleswig and Holstein, however, reared its head when people in southern Schleswig, mostly Germans, wanted closer ties to Germany, while people in northern Schleswig, mostly Danes, wanted out. A solution was found, some thought, in resurrecting an independent state within the Confederation under the rulership of the next prince in line from the House of Oldenburg who was not the Danish king: the Duke of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Augustenburg.

So wait, there’s yet another line of Schleswig-Holstein dukes? I thought you said the Holstein-Gottorp division that ended in 1773 was the last? Sadly not, dear reader. However, the junior branches of the House of Oldenburg-Denmark that were formed after that initial split of 1544, were of a slightly different kind. They did not rule in condominium with the Danish Crown like Gottorp did, but as ‘partitioned lords’ (Abgeteite Herren). This meant that while they gained a certain portion of revenues from the duchies of Schleswig and Holstein, and were granted residences from which they took their names, they did not share in the Crown’s sovereignty over Schleswig, they did not have an independent seat in the Imperial Reichstag for Holstein, and they couldn’t mint their own coins or raise their own armies. These various junior lines—and there were many—all descend from Prince Hans, the younger brother of King Frederick II of Denmark-Norway.

In 1564, Hans was given the castle of Sønderborg, in Schleswig, which is today one of the southernmost parts of Denmark, on an island just offshore of the east coast of Jutland. It was a fortress built by the king of Denmark in the 1150s, expanded in the 14th century, and now converted into a princely residence in the 1570s. A notable addition at this time was the ducal chapel, which is considered one of the best preserved Lutheran castle chapels. A later duke, Christian Adolf I, went bankrupt in 1667 and sold this castle to the Danish Crown, and moved his family to his wife’s patrimony at Franzhagen, until this line died out in 1709. Sønderborg castle was remodelled in the 1720s, and was once again given to the cadet branches (in 1764), but it was never again used as a ducal residence, but as barracks or a warehouse. It was sold to the Danish State in the 1920s and is today the museum for regional history about the Duchy of Schleswig.

The heirs of this first branch were the next branch down, the dukes of Augustenburg. This branch was founded in the early 17th century, and eventually took its name from a new castle built in the 1660s on a fjord on Als island (not far to the east from Sonderburg), and named for the wife of the first duke of this line, his cousin Augusta of Schleswig-Holstein-Glücksburg. Many of these junior branches continued to interlock the family through endogamous marriages, or they mingled with the local Danish and north German nobility, and they earned their living by serving in foreign armies. The castle of Augustenburg was replaced in the 1770s, with the attractive building of today with its yellow walls and blue tiled roof.

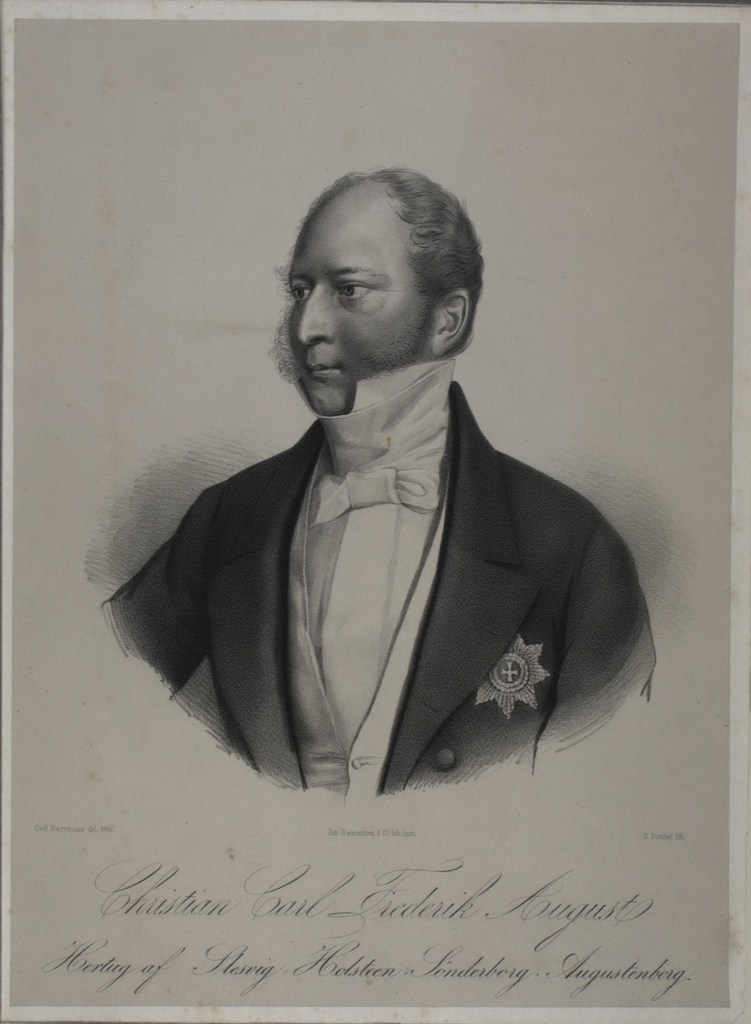

By the mid-18th century, the duke of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Augustenburg was the senior cadet prince of the House of Oldenburg, and began to aim higher socially and politically. In 1786, Duke Frederick Christian II married the daughter of the Danish king, a potential heiress, since the Danish kingdom had no laws against female succession (though Holstein, as a German state, did). His younger brother, Christian August, was invited by the Swedish people to become their Crown Prince in 1809, but he died a year later before he could succeed to the throne. By the 1840s, as it became clear that King Frederick VII of Denmark would be childless, Duke Christian August II put forward claims, as senior male heir and son of a Danish princess. His sister, Caroline Amalie, was also the Queen of Denmark. He seemed the perfect candidate. But his marriage to a woman of non-princely rank (though interestingly, still endogamous, since she was from one of the illegitimate lines of the House of Denmark, Danneskjold-Samsø) made him unsuitable. Nevertheless, pressed by German nationalists in 1848, the Duke set up a government in Kiel of an independent Schleswig-Holstein and sparked the first of the Schleswig Wars between Denmark and the German Confederation, a temporary victory for Denmark, supported by the Russian Tsar, as nominally head of the Holstein-Gottorp branch and guarantor of Danish supremacy in the region.

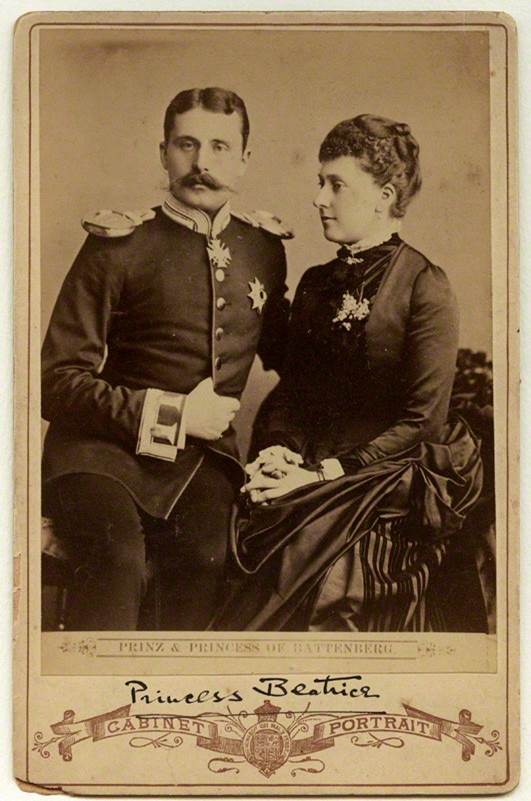

The Duke’s son, Frederick, pressed the family’s claims again after the death of Frederick VII of Denmark in 1863, and sparked the second Schleswig War, in which Prussia and Austria forced Denmark to give up its claims to both Schleswig and Holstein. Great Britain was involved, as a guarantor of the earlier peace settlement, and the issue became familial as well as political in the years following the war when Queen Victoria’s daughter Princess Helena married the Duke’s younger brother, Prince Christian, who relocated to London. A few years before, the daughter of the rival (and successful) claimant to the Danish throne, Princess Alexandra of Glücksburg, had married the Prince of Wales, and for the rest of her life, Alexandra is said to have passionately resented Prussia for having invaded and humiliated her Danish homeland. It would be interesting to investigate the relationship between Christian and Alexandra…

The defeated family of the Duke of Augustenburg was vanquished and moved to estates they owned in Silesia (Primkenau Castle, now Przemków in Poland). The castle of Augustenborg (the Danish spelling) was abandoned to the Danish Crown, then sold to the state in the 1920s, and is now a psychiatric hospital. The family built a new palace at Primkenau in the 1890s, but this burned down in 1945, and nothing remains.

The family did retain a residence in Denmark, Gråsten Castle, originally a 16th-century hunting lodge, not far from Sønderborg, which was also sold to Denmark in the 1920s, and became one of the favoured summer residences of the Danish royal family in the 20th century, and still today.

The son of Princess Helena of Great Britain (aka ‘Princess Christian’), named Albert (of course), became the last titular duke of this line, and with his death in 1931, the line of Augustenburg came to an end, leaving their claims to the duchies of Schleswig and Holstein to the Duke of Glücksburg.

This finally brings us to the line of Glücksburg. There had been several other branches in the 17th and 18th centuries, notably the dukes of Plön with their fantastic castle on a hill overlooking a lake (in Holstein, halfway between Kiel and Lübeck), famous for its library and gardens. These dukes had run into some problems, by becoming Catholic and joining the service of the Emperor in Vienna, and when their line died out in 1761, the Danish king was happy to take over their lands and made their palace one of his favoured summer residences. After the 1860s, once Holstein was lost to Denmark, it became a Prussian military academy, and Plön Castle has remained a prestigious private academy ever since.

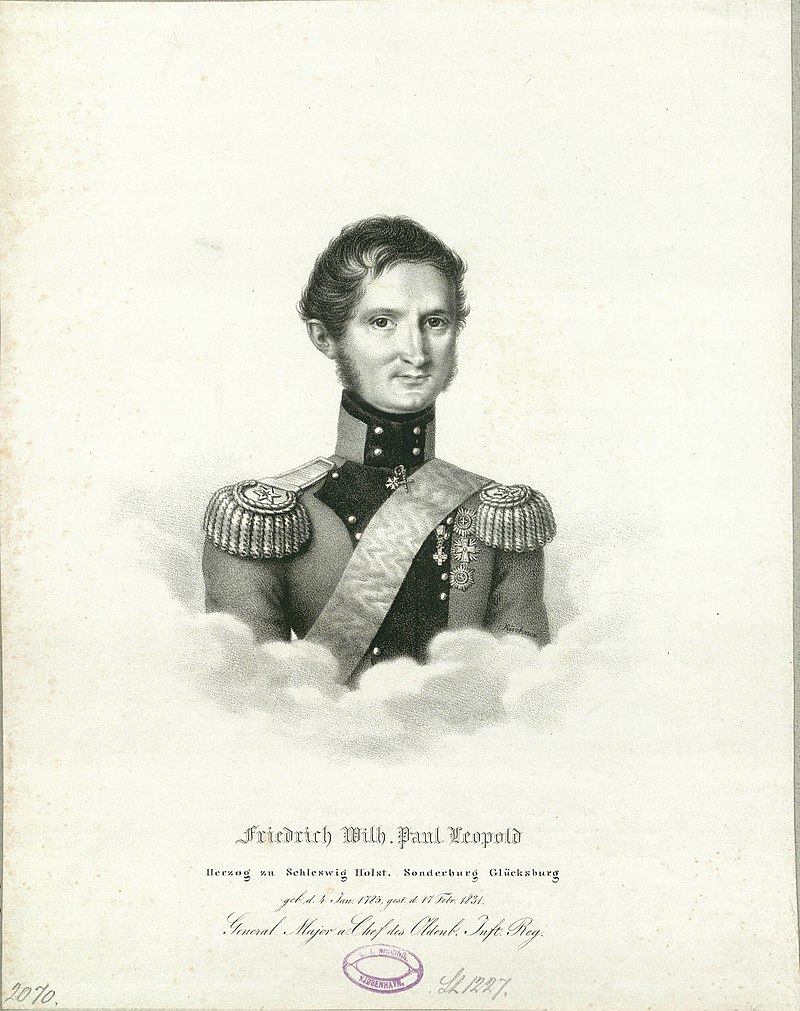

The most junior branch was given no significant estates at all in Schleswig or Holstein, and took their title, Beck, from an estate they purchased in 1605 far to the south in Westphalia, near Minden (fairly close to their kinsmen’s County of Oldenburg). There they built Haus Beck in the 1640s, which they sold in the 1740s. As a princely line quite remote from any chance of a royal throne, this branch ranged widely across Europe, in service of other monarchs, as can be seen in their quite cosmopolitan marriages, from East Prussian Dohnas, a Piedmontese contessa, a Russian Prince Bariatinsky, and the Duke of Silva-Tarouca, the Portuguese-born advisor and minister of Empress Maria Theresa of Austria. Things began to change with the 1810 marriage of Duke Friedrich Wilhelm to Louise of Hesse-Kassel, a grand-daughter and potential heiress of King Frederick V of Denmark. Although a German prince, her father served as a Danish Field Marshal and governor of the duchies of Schleswig and Holstein, so the Duke and Duchess of Beck became quite close to the Danish court.

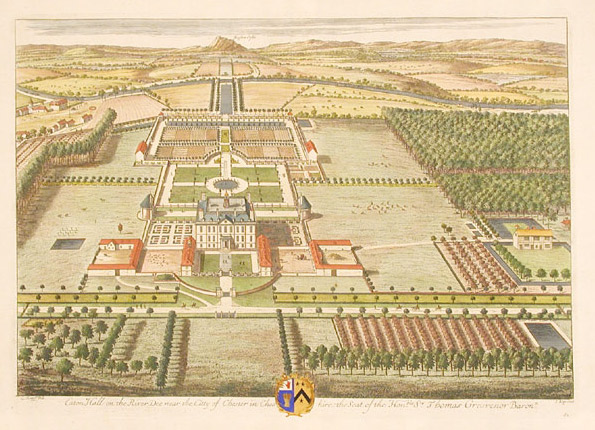

As a mark of favour, in 1825, Louise’s cousin, King Frederick VI, granted the couple the Castle of Glücksburg, which had been the seat of an earlier Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg branch that died out in 1779 (but whose widow had been allowed to remain in situ until her death in 1824). The castle, known as Lyksborg in Danish, is today one of the northernmost points in Germany, on an island in the Flensburg Fjord. It was built in the 1580s on the site of a former monastery, Rüde Abbey, which was dismantled in the Reformation and the bricks re-used for the new ducal residence. Much of the Renaissance decoration on the exterior was removed in the more sober 19th century, and it is one of the few castles named in this posting that remains the property of the family.

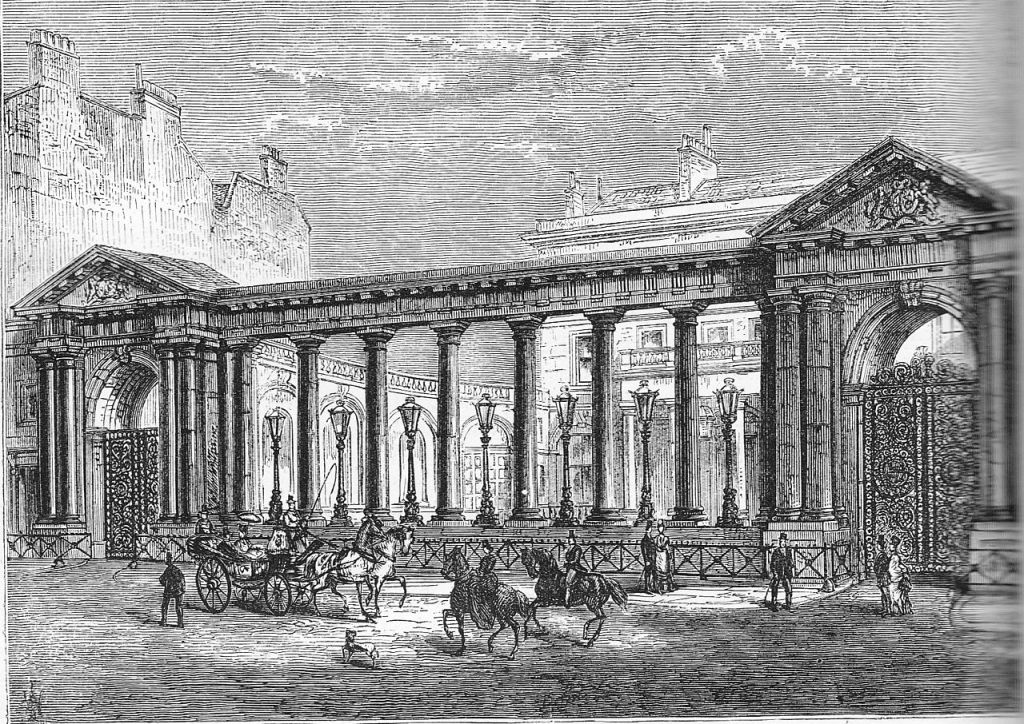

The link between the Danish royal family and the dukes of Glücksburg was strengthened with the marriage in 1838 of Duke Charles with Princess Wilhelmina, daughter of Frederick VI, and former wife of Frederick VII (I know, this is confusing), and a few years later by his younger brother, Christian, with another Hesse-Kassel princess with a Danish mother. Although Prince Christian was the fourth of seven sons, he had been the godson and namesake of King Christian VIII, and raised at the Danish court as a surrogate royal prince. When the thorny question of the Schleswig-Holstein succession came up in 1848, he was chosen to succeed the childless Frederick VII, as someone with succession rights to both Denmark and the contested duchies, and was given the title ‘Prince of Denmark’ in 1852, in a treaty agreed to by all the major powers of Europe. His family moved into the elegant Yellow Palace in Copenhagen (where the future Queen Alexandra of Great Britain was born), and he succeeded to the Danish throne in 1863, and moved into the Amalienborg Palace.

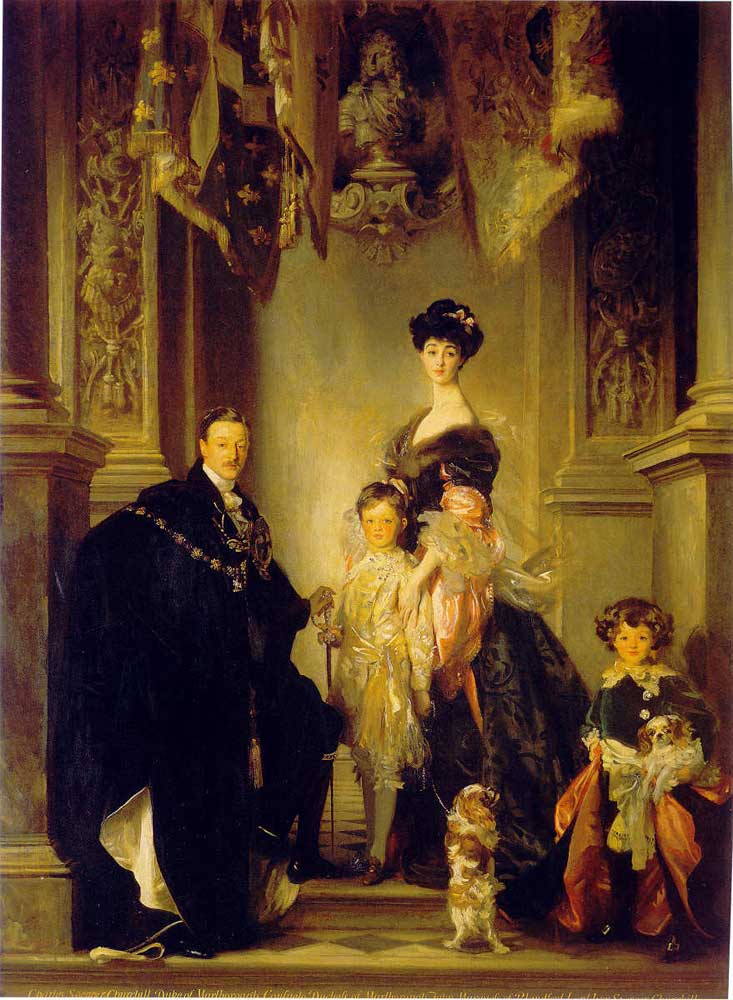

That very same year (in fact earlier), Christian’s second son, William, was selected to become second monarch of the newly independent Greek Kingdom (taking the name Georgios). Alexandra had also married the Prince of Wales in 1863, and her sisters would also marry heirs: to the Russian throne and the defunct Hanoverian throne. Their descendants spread out across all the thrones of Europe, giving Christian IX the nickname ‘Grandfather of Europe’.

In addition to Denmark and Greece, a further throne was added in 1905 with the selection of Prince Carl to become king of a newly independent Norway (as Haakon VII). The Greek princes retained their position as potential heirs to the Danish throne, hence the full title of Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, when he was born in 1921 at the Villa of Mon Repos in Corfu, as ‘Prince of Greece and Denmark’.

A year later, in the face of a defeat in the Greco-Turkish war, King Constantine I was forced to abdicate and much of the family, including Philip’s father Andrew, fled the country. The Greek monarchy would be removed and restored numerous times over the succeeding decades, and was finally sent away permanently in 1974. The last king, Constantine II, may have wished to solidify his ties with Denmark by marrying Frederick IX’s second daughter, Anne Marie (royal purists may in fact suggest that, as Queen Margarethe II married a non-royal person, Anne-Marie and her ‘double-Oldenburg’ offspring should succeed to the Danish throne, but no one would take them seriously). Oldenburg rule in Norway continues today with King Harald V and his very popular son, Prince Haakon Magnus. As an interesting aside, there was a potential for an Oldenburg takeover of the British throne much earlier, if Queen Anne and her husband, Prince George (Jørgen in Danish), son of King Frederick III of Denmark, had generated a dynasty. As is now well known thanks to the movie The Favourite, all of Anne’s seventeen pregnancies resulted in stillborns or infant deaths, with the single son, William, living to the age of 11. There is therefore a tiny piece of the House of Oldenburg in Virginia, through the namesake of Duke of Gloucester Street, the main thoroughfare in Colonial Williamsburg.

In the 21st century, none of these royals in Denmark, Greece and Norway (not to mention Spain, as still presided over by matriarch Queen Sophia, sister of Constantine), the Duke of Edinburgh or the Prince of Wales, are technically the head of the family. Nor is it the Grand Duke of Oldenburg. The House of Oldenburg, or the House of Glücksburg, is ‘officially’ led by Prince Christophe, Duke of Schleswig-Holstein (b. 1949), who, together with his wife, from the Westphalian princely family of Lippe, heads the family foundation that runs the museum at Glücksburg Castle, as well as extensive landholdings in the region, based from his residence Gut Grünholz, an 18th-century manorhouse bought from the von Moltke family in the 19th century, east of the town of Schleswig.

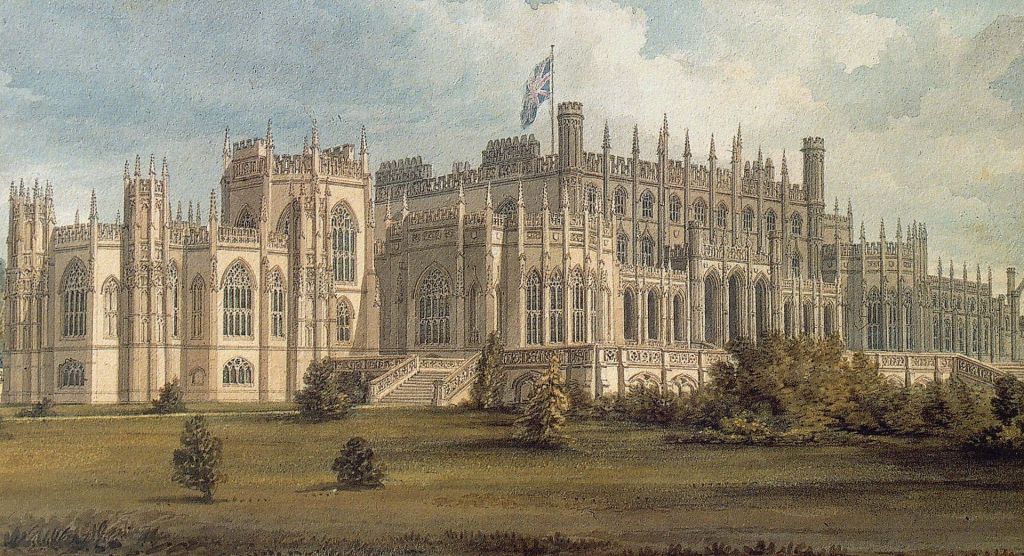

Unlike many German princely families following the collapse of the German Empire in 1918, the Glücksburgs maintained a fairly low profile for the succeeding generations, marrying well (so far, always with equal marriages by traditional German royal standards). Christophe’s grandfather, Duke Friedrich, head of the entire Schleswig-Holstein family after the extinction of the Augustenburg line, is interesting to note, however, in the context of the life of Prince Philip, in that he was a follower of Kurt Hahn, founder of Salem School, which transferred (along with Philip) to Gordonstoun in Scotland in 1934. After the war, Friedrich founded his own school along similar lines at one of his estates, Louisenlund, today one of the poshest private schools in Germany, located on the banks of the Schlei, nicely taking us back to the dynasty’s earliest origins.

Castles visited in this blog: Oldenburg and Rastede in Lower Saxony; Gottorp, Kiel, Plön, Glücksburg and others in Schleswig-Holstein; and Sønderborg and Augustenborg in Denmark (since the 1920 referendum dividing Slesvig/Schleswig).

(images taken mostly from Wikimedia Commons)