The Duke of Saint-Simon is one of the most famous memoirists of all time, and the most meticulous and detailed account available to us for the court of Louis XIV of France. He’s not always the most reliable source, as he particularly enjoys boasting, about his powerful friends, about his own intellect, and so on. One of his most persistent boasts in his memoirs is that his lineage is impeccable, in ancientness and nobility, and that he therefore deserved to be treated with the utmost of deference (which he rarely got), and deserved a seat at the table of royal government. Yet how much do most people interested in the history of Versailles know about this lineage? Who were these exalted ancestors of the Duke of Saint-Simon? Most specialists of the history of the French court or of French literature of the 18th century probably could not tell you.

On another level entirely, the name Saint-Simon means something else to historians of a different stripe, those who are interested in the social and political movements of the early nineteenth century. ‘Saint-Simonians’ were those who followed the ideologies of the Count of Saint-Simon, a political and economic theorist who called for a form of socialist utopia in which science and industry would drive society. The two men, the Duke and the Count, were in fact distant cousins, though their ideologies were worlds apart.

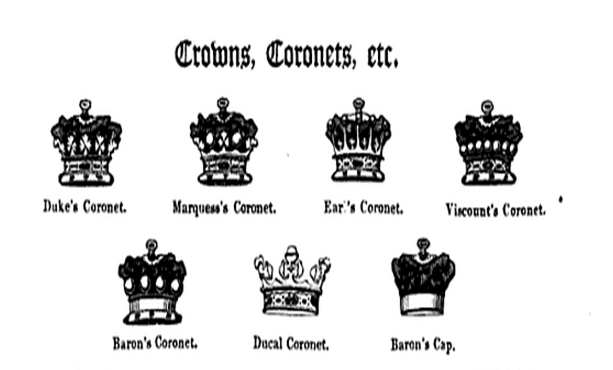

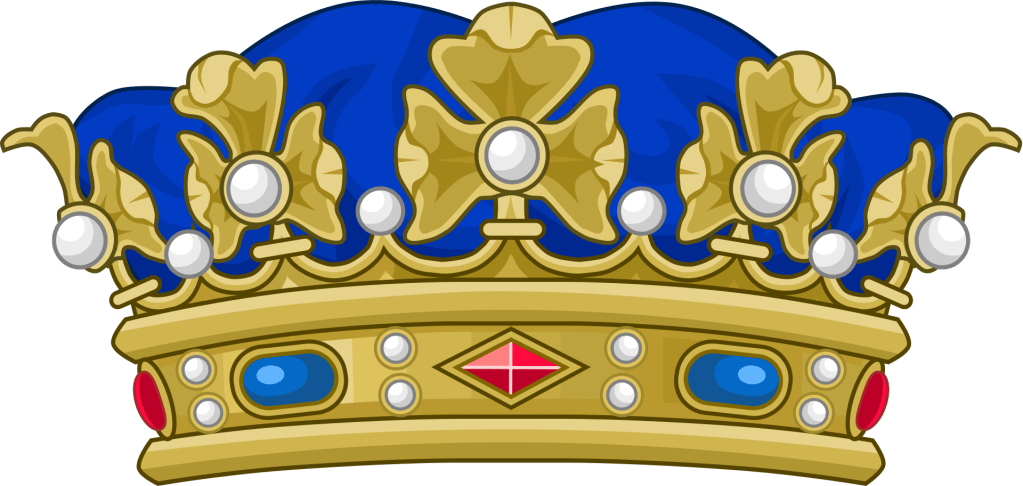

Both the Duke of Saint-Simon and the Count of Saint-Simon were members of the family of Rouvroy, which did indeed have ancient roots. The small towns of Rouvroy and Saint-Simon are both in the far north of France, in Picardy—the village of Saint-Simon in particular is in the easternmost part of the Province of Picardy, the Vermandois, one of the most ancient feudal counties of France. The earliest known members of the family emerge from medieval documents as having close ties to the counts of Vermandois, as vassals, officers and agents, and this proximity is what probably led to the exaggeration by the Duke of Saint-Simon in his writings that they were not just servants of the Vermandois dynasty, but members, from a junior branch. What makes this claim even more noteworthy is that the House of Vermandois itself was a junior branch of the Imperial dynasty of Charlemagne. By claiming direct lineal kinship with the Carolingians, Saint-Simon was, not very subtly, asserting that his family had a better claim to the French throne than Louis XIV, whose ancestor, Hugh Capet, ‘usurped’ the throne from the legitimate Carolingian heirs in the late 10th century. (see the chart at the bottom of this page)

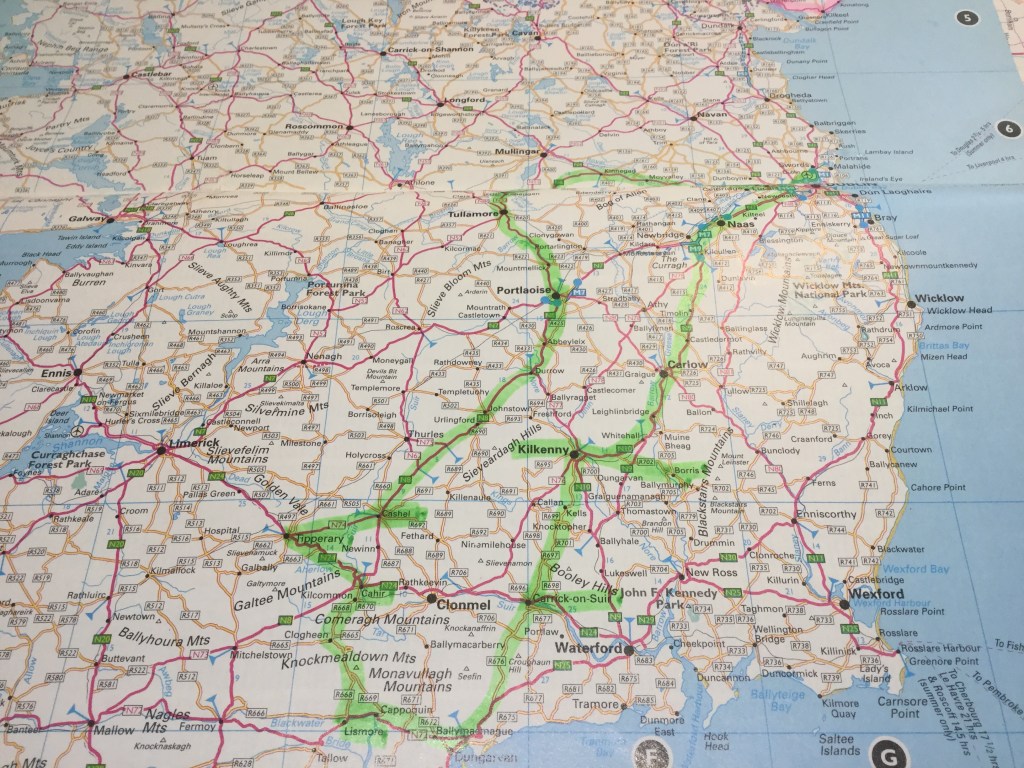

Upon closer examination, the weak link in this dynastic story seems to be a certain Eudes de Vermandois ‘the foolish’, who, according to Père Anselme’s massive royal genealogy of the late 17th century, only appears in some accounts, while his more well-documented sister, Adèle, is known to have transmitted the county by marriage back into the royal house of France. Anselme adds that those who mention Eudes explain that he had been disinherited in about 1077 because he was ‘of little understanding and without government’ (ie, he was probably mentally ill). Nevertheless, Eudes is said to have married an heiress called Avide, daughter of the Lord of Saint-Simon. He adopted her name and started a new dynasty. The last lord of Saint-Simon of this line died around 1330, leaving his lands to his sister, Marguerite, who in 1332 married Mathieu de Rouvroy, ‘le Borgne’ (‘one-eyed’). Mathieu had lost an eye in battle in service to the Capetian monarchs in battles along the northern frontier of Picardy and Flanders, and was appointed governor of Lille. His ancestors had filled important leadership roles like this, but the most prominent were on the far side of the Kingdom, Renaut and Alphonse both serving as governors of the Kingdom of Navarre in the late 13th and early 14th centuries. Mathieu’s son, Jean, would also lose an eye in battle, and similarly sported the nickname ‘the one-eyed’, before he was killed at Agincourt in 1415. Those looking for physical remains of the Rouvroy de Saint-Simon family won’t find very much in Picardy. Fragments of ancient castles can be found at Saint-Simon, Rouvroy, Clastres and other family estates, but most of the land today is wide rolling countryside. For imposing châteaux, we’ll need to travel south, to later centres of power, to the northwest and southwest of Paris (Sandricourt, La Ferté-Vidame), and even further to the lands northeast of Bordeaux (Ruffec and Giscours)—though even with these, they are either ruins or much later rebuilds.

But before the family expanded south, they expanded further north. Before he died, Jean de Rouvroy married a Flemish heiress, Jeanne d’Haverskerque, Lady of Rasse (or Râches, in Flanders), and their two sons founded the two main lines of the House of Rouvroy-Saint-Simon. The elder, lords of Saint-Simon and other properties in Vermandois and Picardy, rose through service to the late medieval dukes of Burgundy (who governed Picardy) and kings of France, were named viscount of Clastres, but never fully joined the ranks of the grandees of France until the eighteenth century, aided by the pre-eminence of the junior branch, the lords of Rasse. We will return to the senior branch below. The junior branch of Saint-Simon-Rasse held several lordships near Orchies and Douai, and were appointed to important military posts along the sensitive frontiers of Flanders, until one of these rose to the high rank of maréchal de camp in 1591. His son, Louis, was also a commander in the wars of religion in the 1580s-90s, and, like many nobles, bankrupted his family in supplying his own men with food and supplies. His three sons, however, managed to rebuild, and even surpass the family fortunes, with the middle son in particular, Claude, becoming a royal favourite. This was the father of the famous memoirist.

Claude de Rouvroy, Comte de Rasse, was born in 1607, and was appointed to be a page in the household of the Dauphin Louis. Once the Dauphin became king, as Louis XIII, Claude remained one of his close companions, a Gentleman of his Chamber, named Premier Equerry of the King in 1627, then only a year later, Master of the Wolf Hunt of France (Grand Louvetier), one of the Great Offices of the Crown. Like most Bourbons, Louis XIII passionately loved hunting, so it is significant that his closest friends were named to positions like Master of the Hunt, Master Falconer, etc; this ensured that they were always near him in his day-to-day activities. Claude was also one of the young men of the court best known as a dancer, an important and often politically charged evening pastime, and indeed, he remained a protector of musicians for the rest of his life. Gossips who always wondered why the King had thus far not produced any children with the Queen (and why he had no mistresses) naturally jumped to the conclusion that the King was having an affair with the attractive Claude de Rouvroy. And maybe he was.

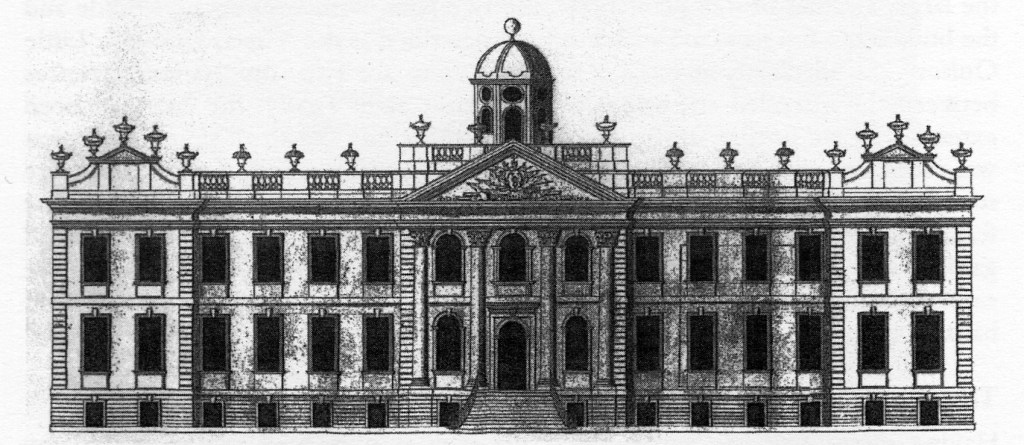

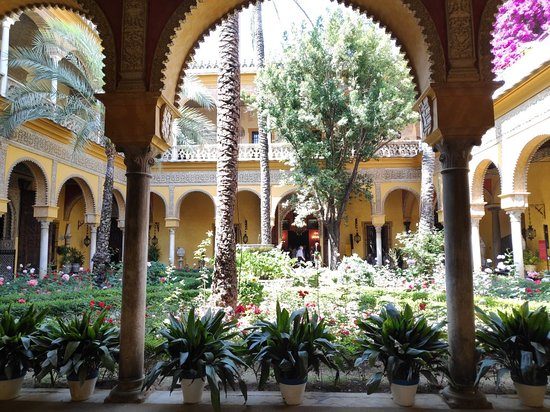

In 1630, Claude was named governor of the fortress of Blaye, a very lucrative post as one of the keys to controlling the defense of Bordeaux and Aquitaine, and governor of the of royal châteaux of Versailles and Saint-Germain-en-Laye. By 1635 he had accumulated enough money through his various court offices and government appointments to purchase a grand estate at La Ferté-Vidame, in the former province of Perche (southwest of Paris, bordering on Normandy) which came with an interesting title of ‘vidame’ de Chartres. The cathedral town of Chartres was about 50 km to the east, and the vidames were secular lords who aided the bishop in the administration of his lands. The lords of La Ferté were vidames of Chartres from the early 12th century; their castle was older, built in the 10th century, and, as rebuilt in the 14th by the Vendôme family, would become the Rouvroy family’s primary country seat for the next century and half.

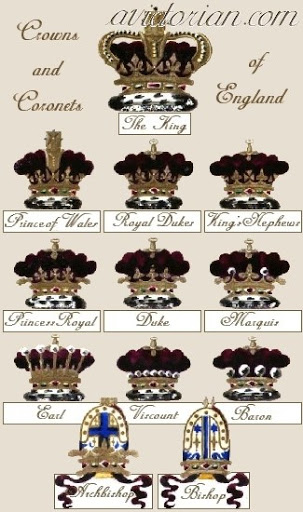

The royal favourite, Claude de Rouvroy, also convinced his distant cousins to cede the original family lands to him—the seigneuries of Saint-Simon, Clastres and others in Vermandois—and these were erected into a duchy-peerage by the King in 1635. But the new Duke of Saint-Simon was almost immediately disgraced—for what sounds like a pretty flimsy reason of defending his uncle who had failed to defend a key fortress in the north, though 1636 was a fairly stressful year for the King, as Spanish armies came within a hair’s breadth of invading the Isle de France and Paris itself. I wonder if it didn’t have more to do with the fact that Cardinal Richelieu, the real power in France, was finding it difficult to control the King’s favourites and worked for their removal (one of Louis XIII’s only real ‘mistresses’, Louise de La Fayette, was also sent away later that year), in part so he could place his own creature within the King’s intimate circles: note the swift rise of the young and debonnaire Marquis de Cinq-Mars, a client of the Cardinal’s, was only a year later.

The 1st Duke of Saint-Simon retired to Blaye and did not return to favour at court until the King was on his deathbed in 1643 (and notably following the disgrace and horrific execution of Cinq-Mars in late 1642). The Duke’s son claims in his memoirs that the King, overjoyed with the reconciliation, promised to name his erstwhile favourite Master of the Horse (Grand Écuyer), one of the top court offices in France, and that he died before he could make it official. Saint-Simon firmly believed the office was then ‘stolen’ by Henry de Lorraine, Count of Harcourt, a favourite of the new Queen Regent, and it was then passed on to his son and grandsons in the reign of Louis XIV (they did in fact control this prestigious office until the Revolution). This ‘theft’ (for which there is no real evidence beyond the word of Saint-Simon) is the source of many, many pages of outrage and bile in the Memoirs of Saint-Simon towards the House of Lorraine. In fact he did lose the position of Master of the Wolf-Hunt and that of Premier Equerry of the King, in the new regime of the Regent Anne, but one does wonder why exactly the former consort of Louis XIII disliked Saint-Simon so much.

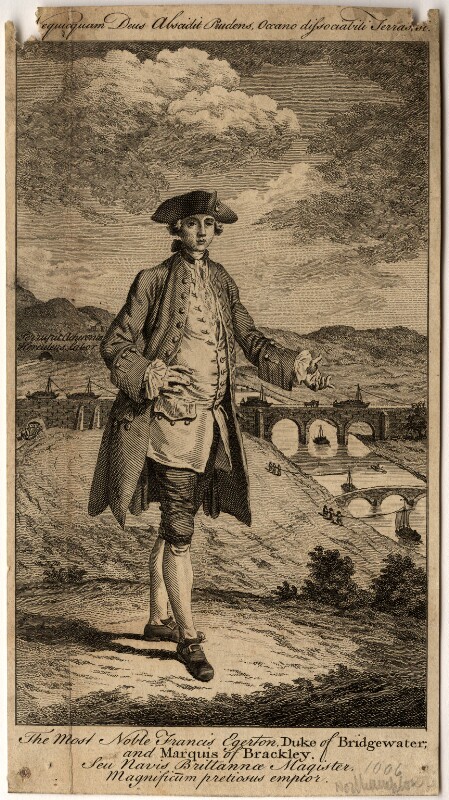

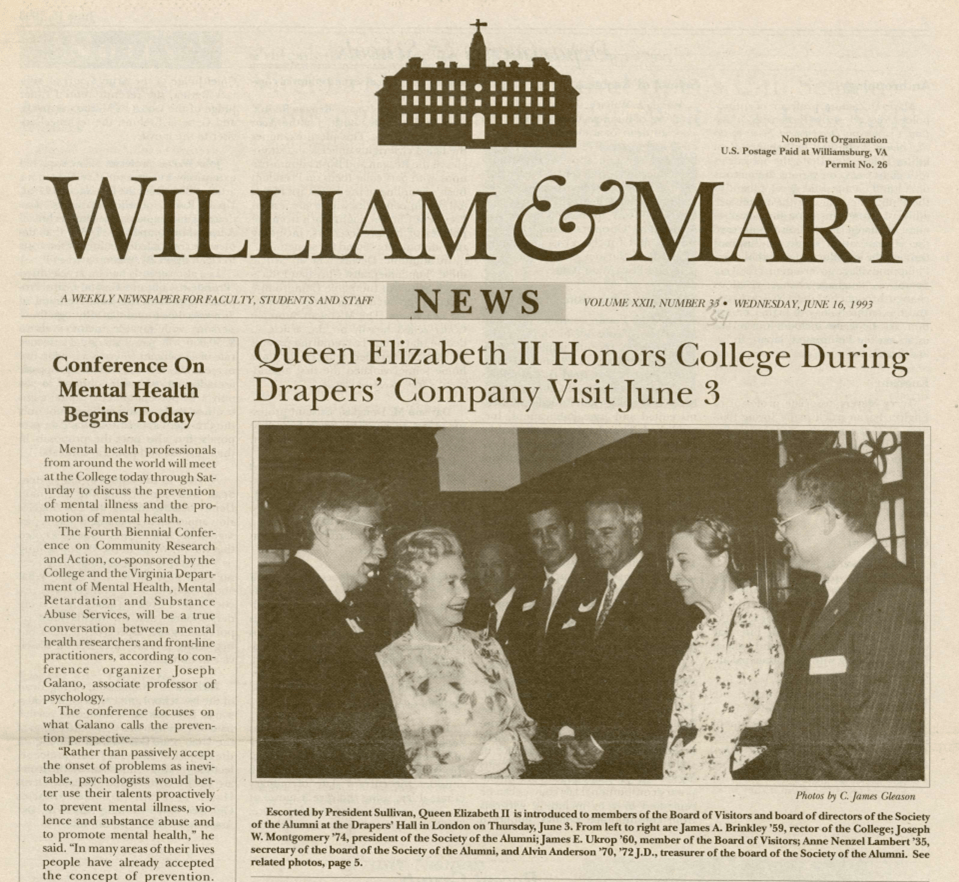

The 1st Duke of Saint-Simon outlived his royal patron by fifty years (that’s right, fifty) but is almost never mentioned in the histories of the Regency of Queen Anne or the court of young Louis XIV. His elder brother, Charles, Marquis de Saint-Simon, was more prominent: a lieutenant general and captain of the château of Chantilly in the 1630s-50s, the primary seat of the Prince of Condé, first prince of the blood, and one of the most powerful men in the Kingdom. The Marquis also made the first marriage in the family from amongst the high aristocracy, Louise de Crussol, daughter of the Duke of Uzès, and Dame d’honneur of Queen Anne. Charles introduced his wife’s daughter from a previous marriage, Diane-Henriette de Budos de Portes, to his brother Claude, and they were married in 1644. But neither Charles nor Claude had a son to carry on the name or the title, so Claude remarried, at age 65, to try to beget an heir. The bride was the 32 year old Charlotte de l’Aubespine, Dame de Ruffec, daughter and co-heiress of the Marquis de Châteauneuf and Eleonore de Volvire, Marquise de Ruffec. Ruffec was a large estate in Angoulême (now the Department of Charente) north of Bordeaux. A son, Louis (known as the Vidame de Chartres as heir) was born in 1675, but as he complains in his memoirs, just as his father was introducing him to the world of the court and helping to start his military career, he died in 1693.

The 2nd Duke of Saint-Simon, the memoirist, therefore had to make his own way. His aunts and uncles were dead, and his elder half-sister too, Gabrielle-Louise, who had married very well, to the Duke of Brissac, but died with no children. So Saint-Simon had no well-placed in-laws or cousins. He was not entirely without support, however: the King was in fact his godfather, which entailed a certain level of protection, and certainly had a hand in his marriage, in 1695, to a daughter of another duke, and one very much in favour, Guy-Aldonce de Durfort, Duke of Lorges, Marshal of France. The new Duchess of Saint-Simon, Marie-Gabrielle, was said by many to be the more successful courtier of the couple, and it surely humiliated the Duke when, in 1706, the King talked about appointing him ambassador to Rome—finally a prestigious posting!—but his advisors counseled him sharply to do nothing without first seeking the advice of his wife.

The Rome posting never materialised, and the King never did give the Duke of Saint-Simon the kind of appointment he felt he deserved in his administration. Nor was his military career any more successful, and after being passed over for a promotion in 1702, he quit the army, and made a big show about it, thus losing any chances he may have had of ever returning to the King’s favour. His wife, meanwhile, continued to thrive, and in 1710 was appointed Dame d’honneur (chief lady-in-waiting) to one of the royal princesses, the King’s favourite grand-daughter (via his illegitimate daughter), the Duchess of Berry. The Duke placed his hopes in this next generation, the grandchildren of the King, and became a member of the circle of the Duke of Burgundy, heir to the throne from 1711. The two young men shared a vision of a new France that would be built after the old king would (finally!) die, a kingdom based on traditional values of Christian piety, and especially respect for the old aristocratic families, like Saint-Simon’s of course, who had been cruelly abased and so ignored by the Sun King in his vanity and false notions of absolutism in government. At least this is how Saint-Simon viewed it, but these ideas are supported by the writings of the Duke of Burgundy’s former tutor, the Archbishop Fénélon, whose thoughts on this subject had earned him exile from the court. All they had to do was wait: Louis XIV was now 73 years old.

These plans for a bright future were dashed however, when the Duke of Burgundy died, in the Spring of 1712. The old king Louis XIV finally died himself in 1715, and Saint-Simon saw some hope in the new regime of his friend and close contemporary in age, though quite different in temperament, the Duke of Orléans, who now became regent for the child-king, Louis XV. Saint-Simon’s vision of a decentralised government where the grand old aristocrats were once again given premier place in running the state was tested by the Regent (in various councils, known as ‘polysynody’), but failed miserably since all the aristocrats did was bicker over issues of precedence and their own special interests. Unable really to find his place on the various governing councils of the Regent, the Duke looked elsewhere for a place to express his superior rank, and was gratified with the post of Extraordinary Ambassador to Spain in 1721, with the specific task of requesting the hand of the Infanta Mariana Victoria for Louis XV. His mission was successful in that a marriage contract was signed (though later rejected), but also personally, in obtaining the great favour from the King of Spain (the former Duke of Anjou, another of Louis XIV’s grandsons) of having his first son awarded the Order of the Golden Fleece, the highest honour in Spain, and his second son the title of Grandee of Spain, a rank which was recognised at the French court as equal to a dukedom, with all its privileges. That same year, he negotiated a prestigious marriage for his only daughter, Charlotte, with a prince, Charles-Louis-Antoine de Hénin-Liétart, Prince of Chimay, who was one of the leading grandees of the Spanish Netherlands, a lieutenant-general in both French and Spanish armies, had a Cardinal-Archbishop for a brother, and, even more thrilling for Saint-Simon, was considered to be a sovereign prince, albeit in the tiny principality of Revin and Fumay (in the Ardennes). This family even claimed descent from the Carolingians, via the ancient House of Alsace, so Saint-Simon must have been the happiest father-of-the-bride who ever lived.

But the ambassadorial trip to Spain (and undoubtedly his daughter’s significant dowry needed to attract the Prince of Chimay) ruined the Duke of Saint-Simon’s finances, and his future in politics was dashed when the Regent Orléans fell from power and then died, in 1723, and his replacement at the head of government was an old enemy of Saint-Simon, Cardinal Dubois. Saint-Simon retreated to his château at La Ferté-Vidame, and spent the next decades writing his famous memoirs. The grand château still retained its medieval appearance, with eight great towers. The Duke did maintain a residence in Paris, but he moved from place to place—the building at 17 rue du Cherche-Midi in the 6th arrondissement (not far from the Luxembourg Gardens) bears a plaque indicating that this was where he wrote the memoirs—but he was not often seen at court.

The 2nd Duke of Saint-Simon knew he needed to try to maintain to the family’s position at court and in the government while he languished in the provinces. In 1727 he oversaw the marriage of his elder son, Jacques-Louis, to a daughter of the Duke of Gramont, and in 1728, he formally resigned his peerage to him, thus allowing him to sit as a peer in the Parlement of Paris and appear at court in the rank of a duke. To differentiate father and son, the latter was known as the ‘Duke of Ruffec’, taking his title from his grandmother’s marquisate near Bordeaux. When Jacques-Louis died in 1746, the old Duke once again resigned his peerage, now for the second son, Armand-Jean, who was now legally the 4th Duke of Saint-Simon, but he too predeceased his father, in 1754. And when the by now fairly ancient memoirist-duke died himself in 1755, there only remained his daughter, the Princess of Chimay (who had no children), and one daughter by the eldest son, Marie-Christine, who had married the Comte de Valentinois, younger brother of the Prince of Monaco.

The Countess of Valentinois had a very good court career—she inherited her uncle’s title ‘Grandee of Spain’, which meant she was treated as a duchess (or even better, since her Grimaldi husband was ranked as a ‘foreign prince’), and was given the important court office of Dame de Compagnie of ‘Mesdames’ (the unmarried daughters of Louis XV), in 1762, then Dame d’atours of the Comtesse de Provence (the sister-in-law of the future Louis XVI), in 1770, and finally the same princess’s Dame d’honneur, in 1772. Like many court aristocrats of the later 18th century, however, she ran into financial troubles. Although she had inherited the magnificent château and estates at La Ferté-Vidame, and the estates in the south of France at Ruffec, she sold these off: Ruffec to the Comte de Broglie in 1762; and La Ferté to the financier Jean-Joseph de Laborde in 1764 (who significantly remodelled it). Just as she was reaching her apogee, as first lady of the second lady of France, she died in 1774, childless, and with her, the junior branch of the House of Rouvroy.

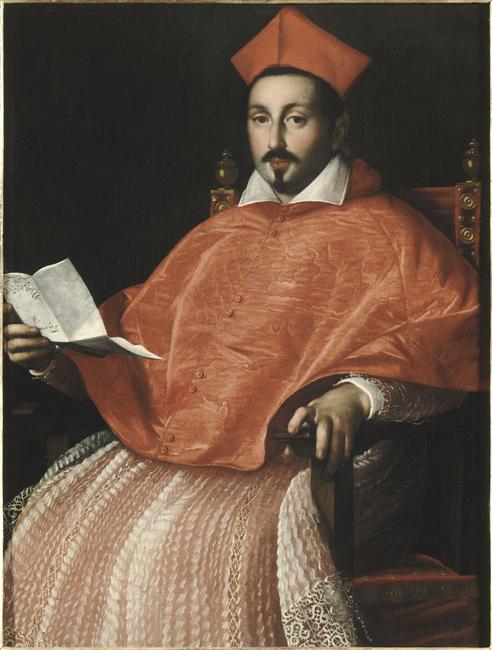

But the memory of the memoirist persisted. The 2nd Duke of Saint-Simon had understood the importance of solidifying the position of all of his dynasty, not just the immediate family, and reached out as a patron to his very distant cousins from the senior line of the family. As early as 1712, he looked after Claude-Charles de Rouvroy-Falvy, who lost his father that year, and helped him acquire a lucrative benefice, the Abbey of Jumièges in Normandy, in 1716. The young Abbot accompanied the Duke on his embassy to Spain in 1721-22, and was first promoted to higher clergy as Bishop of Noyon in 1731, then Metz, in 1733. Neither Noyon nor Metz were amongst the wealthiest sees or the most prominent politically in the French church, but to the status-conscious and history-loving Saint-Simon, they were perfect: Noyon, though one of the smallest dioceses in France, was also one of the oldest, and its bishop was one of the six ecclesiastical peers who crowned the monarch; Metz was formerly an Imperial bishopric and thus entitled to be addressed as ‘prince’ and ‘highness’, or so Claude-Charles thought. His assumption of princely airs and graces (and claims to regalian rights, ie, as if he was a sovereign, some judiciary, some financial), caused the local Parlement of Metz, in 1737, to issue a formal statement prohibiting him from using the title ‘Prince of Metz’. He was a true heir to Saint-Simon. And in fact, the Duke left him his papers in his will, including the famous memoir manuscript, though he never actually took possession due to legal complications, before he himself died five years later in 1760.

The Bishop of Metz in turn had promoted the career of another cousin, from an even more remote branch, Charles-François de Rouvroy-Sandricourt. He was first appointed to be the Bishop’s Grand Vicar (chief administrator), then given his own diocese as Bishop of Agde (on the Mediterranean coast) in 1759. He survived into the world of the French Revolution, but continued the family tradition of clinging to traditional values, refusing to swear the oath supporting the new ‘state church’ of 1790, and succumbing to the guillotine in 1794.

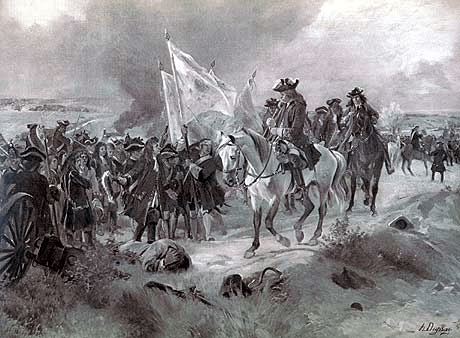

Another cousin, Claude-Anne, from the line of Rouvroy-Montbléru, raised the military profile of the family in the later 18th century, and even managed to revive, in a round-about way, the title of Duke of Saint-Simon. Both Claude-Anne and his brother Claude (a popular family name) served in the French army aiding the Americans in their quest for independence (both of them notably at Yorktown). The younger was named one of the founding members of the Order of Cincinnatus, the hereditary order founded to commemorate the heroes of the American Revolution, and his descendants continued to bear this honour until they died out in the early 20th century. Claude-Anne, a field marshal from 1780, served as a deputy of the Second Estate (the nobility) from Angoulême (where he held properties, notably the château of Giscours) to the Estates General of 1789. Soon after the outbreak of revolution, the Marquis de Saint-Simon (or Marquis de Montbléru) emigrated, to Spain, where he was named a lieutenant-general in the Spanish army and gathered together a group of fellow émigrés to form the Légion catholique et royale des Pyrénées (aka Légion de Saint-Simon) in 1793. In 1796, he was named by Carlos IV second in command of the Army of Navarre, Captain-General of the Province of Old Castile, and colonel of the Regiment de Bourbon, which he led in combat in Majorca, Catalonia, and Portugal. He was rewarded by his services first with the title of Grandee of Spain, first class, 1803, then Duke of Saint-Simon and Capitàn General of Spain (the equivalent of a Marshal of France), by the restored King Ferdinand VII, in 1814. He remained in Spain as colonel of the Walloon Guard, but stayed out of politics. His properties like Giscours has been confiscated and sold, so he remained in Spain, in Pamplona or Madrid, where he died in 1819.

The Duque de Saint-Simon left behind only a daughter, ‘Mademoiselle de Saint-Simon’ who is known today for a dramatic painting by Charles Lafont depicting the moment she begged the Emperor Napoléon to spare her father’s life after he had been captured in 1808.

The Duke’s heir was his nephew, Henri-Jean-Victor, who had led a very different life in the military, serving from age 18 in the armies of the French republic, including campaigns in Spain against the very same royalist forces being led by his uncle. From 1809, he commanded one of the guards regiments of Joseph Bonaparte (Napoléon’s brother) as King of Spain. Like so many aristocrats, the Vicomte de Saint-Simon rallied to Louis XVIII at the Restoration, in 1814, and remained loyal during the Hundred Days, accompanying the King to Ghent, where he was named a maréchal de camp. When his uncle died, Henri-Jean-Victor succeeded as second Spanish Duke of Saint-Simon, and confirmed as a peer of France by Louis XVIII in 1819 (though with the rank of marquis, not duke). Crucially for our story here, he petitioned the King to formally release from state possession the already famous, but unpublished, memoirs of his distant cousin. The first complete version of the Memoirs of the Duke of Saint-Simon appeared under his patronage in 1829-30 in 27 volumes.

The Marquis de Saint-Simon (he didn’t start to use the ducal title until the 1840s) entered royal service; he was an ambassador first in Lisbon, then in Copenhagen, before being named Governor-General of the French colonial possessions in India, based in Pondichéry, in 1834. Recalled in 1841, he played a role in the Senate in support of the monarchy of Louis-Philippe, and was promoted to lieutenant general in the army, though he was ineffectual in preventing the revolution of 1848 that swept this regime from power. As a good political chameleon, he supported the proclamation of the Second Empire in 1851, and was named Senator of France. Late in life, he ceded his rights to the manuscript of Saint-Simon’s memoirs to the publisher Hachette, who produced what is now considered one of the premier editions of the memoirs, edited by Adolphe Chéruel, in 1856-58. As he was dying in 1865, the ‘6th Duke of Saint-Simon’ tried to have one of his sons from his second marriage—born long before the marriage—recognised as a legal heir (and thus potentially 3rd Duque de Saint-Simon, Grandee of Spain), but was rebuffed by all legal authorities in France and Spain.

Had he been still alive, the last member of the family to have left a significant mark on history, Henri de Saint-Simon (he ceased to use a title during the Revolution), might have applauded this attempt to transfer noble status onto the son of double adultery. The Comte de Saint-Simon was actually a double-dose Saint-Simon, with his father heading up the junior branch of Sandricourt, and his mother from the more senior line of Falvy. The line of Sandricourt, an estate northwest of Paris, a marquisate from 1652, had been a distinct branch from the early 16th century. They became in fact more prominent than their cousins at the court of the last Valois kings, but lost prominence under the Bourbons. But they were always there, and in the late 18th century, the numerous brothers and sisters of Count Claude-Henri de Saint-Simon de Sandricourt all served in the army or the navy and at court—one of the most prominent was his sister, Marie-Louise, Dame de Montléart, who succeeded her Saint-Simon cousin as Dame d’honneur of the King’s sister-in-law, the Comtesse de Provence, in 1786. Claude-Henri (who went by Henri) served in America under General Rochambeau, and like his cousin, was awarded the Order of Cincinnatus. He was the King’s Lieutenant in the city and region of Metz, but quit military service to devote himself to industry and plans to build canals and factories.

He embraced the Revolution fully, made a lot of money working for the regime, then lost it all, and turned instead to writing, though not much came of it until 1817, when he published l’Industrie, an important forerunner in the history of socialist thought. More successful though brief, was a periodical he founded, l’Organisateur, to criticise the government and make plans for a better system, but it was shut down in 1820, after only a few issues. He published more books advocating the primary of industry for building a more equitable future, then began to write about philosophy and how a new religion could be forged out of the best parts of Christianity in the service of the state, society and its poorest members. His final work, Nouveau christianisme: Dialogues entre un conservateur et un novateur, was left unfinished when he died in 1825.

Henri de Saint-Simon left no descendants, but his brother, a naval officer, did, and there remains a Rouvroy de Saint-Simon family inscribed in the official lists of the modern French nobility. In fact, one of the caretakers of such lists was Fernand, Comte de Saint-Simon, one of the authorities on the history of the French nobility in the 1970s. There are no grand buildings left associated with the Saint-Simon family (the grand château that exists today at Sandricourt was built in the 19th century by a different family—and had interesting inhabitants in the 20th century, including the American millionaire Robert Walton Goelet, whose first cousin Mary had joined the British aristocracy as Duchess of Roxburghe, and Hermann Goering during the occupation of France in the Second World War).

The still monumental ruins of the château of La Ferté-Vidame, a symbol of the lost world of ancien régime France. Looted and sacked during the Revolution, it became the property of the Orléans family after the Restoration, then confiscated by Napoleon III and sold and re-sold many times, until the French state acquired it and used it as the home of a religious charity aimed at rehabilitating imprisoned women. In 1991 the state ceded it to the department of Eure-et-Loir who has restored the grounds and opened them to the public.

(images from Wikimedia Commons)