Of all the extant dukedoms of the United Kingdom, the dukes of Saint Albans are probably the least well known. They lack a major country house, a ducal seat, to remind the general public of their history and grandeur as a family. They hold no major ceremonial role in the running of the modern monarchy. Yet as one of the four ducal families descended from the illegitimate offspring of King Charles II, their story is an interesting reminder of the close interplay between royalty and nobility in British history. It all starts with a beautiful young actress in a London theatre named Nell Gwyn.

The tale of the Beauclerks, the surname given to them by King Charles, is particularly interesting in the early eighteenth century, as close companions to kings and queens of the Hanoverian dynasty, an interesting scenario where the lingering offspring from one royal house, the Stuarts, remain in close proximity to its successor. The name Beauclerk is unusual—unlike the other three ducal families descended from Charles II, it does not reflect royal lineage (like FitzRoy), or a major Stuart estate (like Lennox), or the name of a major heiress (like Scot). And the title, duke of Saint Albans, granted in 1684, does not reflect any of these associations either (a royal estate like Richmond, or a major noble estate like Buccleuch). It is unclear why either the surname or the title was given to these two sons of the King: Charles, born in 1670, and James, in 1671. ‘Beau clerc’ means ‘fine scholar’, though some have translated it as ‘handsome steward’ a play on the royal surname of Stuart; and some have looked more to an alternative early spelling, ‘Beauclaire’, which connects to the Welsh meanings of their mother’s name, nel gwyn, ‘pretty white’, and is apparently the preferred pronunciation of the name. I have thought that perhaps there was also a bit of historical muddle by Charles and his friends, who wished playfully and romantically to recall the royal liaison from the distant past of ‘Fair Rosamond’ Clifford and King Henry II, though it was Henry I who was nicknamed ‘Beauclerk’. After all, Rosamond’s story does take place in and around Oxford, and the titles given to the elder son at an early age, Burford and Heddington, are both in Oxfordshire. Indeed, one family biographer notes that young Charles’s marriage to the great Oxford heiress Diana de Vere was already envisioned in the early 1670s (though they didn’t in fact marry until 1694), and there is a precedent, in the name ‘earl of Euston’ being granted to another of Charles II’s sons long before his marriage to the heiress of that estate. Some biographers (including her descendant Charles Beauclerk) give Oxford as Nell Gwyn’s birthplace, though evidence for this is scant.

This is all quite speculative, as is the reason for the title Saint Albans, from the town of that name in Hertfordshire which takes its name from the first British martyr, Alban, from the 3rd or 4th century. The Beauclerks were given no lands in that county, nor were they directly connected to the previous earl of Saint Albans, Henry Jermyn, who died in 1684 with no direct heirs (only 8 days before the creation of the dukedom). There was, however, a rumour that Jermyn, who was very close to Queen Henrietta Maria for most of her adult life, was in fact the father of her children, including even Charles II. Could the transfer of the Saint Albans title be a secret clue? If so, it wouldn’t have been a very well-kept secret.

Eleanor ‘Nell’ Gywn is a well-known character from the Restoration period and the court of ‘the Merry Monarch’, Charles II. But much of her actual origin story is mythical—was she a low-born orange seller in Covent Garden who, through luck or talent, became a respected actress, then one of the more sought after courtesans of the Carolean court? Or was she a distant relation of an old and respected Welsh gentry family? I will leave her story to be told by others. What concerns us here is that by about 1668, she was one of the chief favourites of King Charles, and by 1670, had given him a son (to add to those already born to Lucy Walter and Barbara Villiers Palmer), and another in 1671. Young Charles and James Beauclerk were raised close to the court, in houses the King gave their mother on Pall Mall near St James’s Palace in London, or just outside the gates of Windsor Castle in Berkshire. In 1676, Charles was formally given the name Beauclerk and the titles Baron Heddington and Earl of Burford. His brother James was named as his heir, but was soon sent to Paris for his education—the reason for this is unclear—where he died before his 10th birthday.

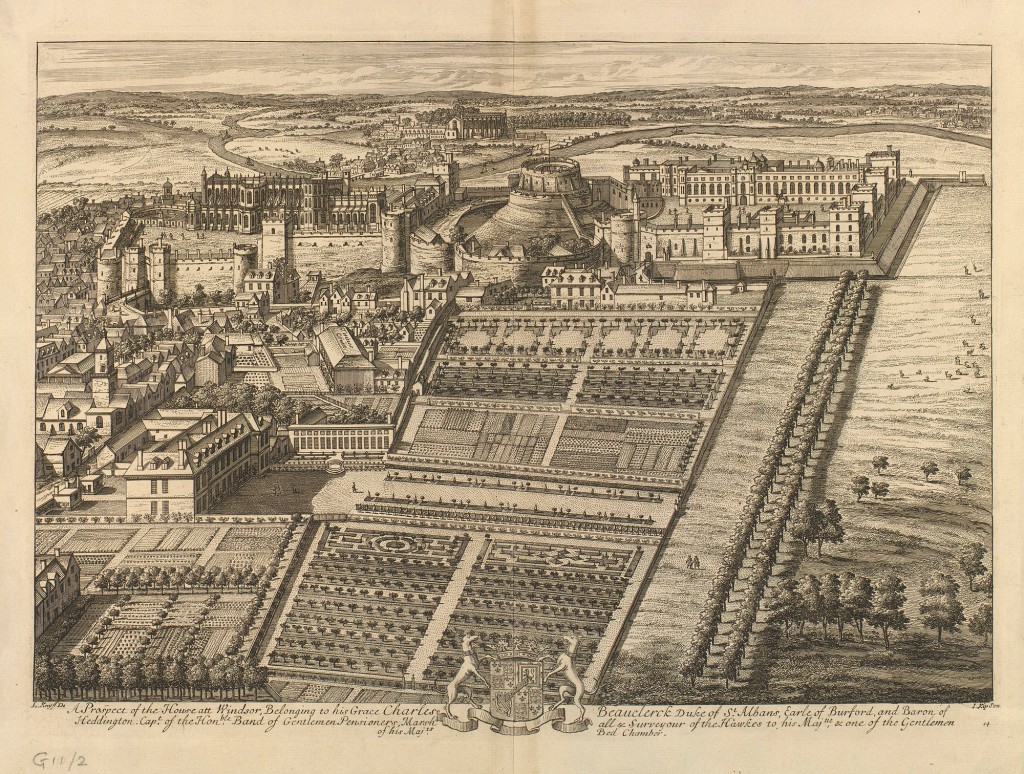

The house his mother occupied in Windsor became known as Burford House, and he inherited it when she died in 1687. It was located just outside the Lower Ward of Windsor Castle, in an area now occupied by the Royal Mews. Its interiors were decorated by royal artists working next door at the castle, notably Antonio Verrio and Grinling Gibbons. The house was improved by the 2nd Duke of Saint Albans, who was also governor of Windsor Castle and Warden of Windsor Forest. One of the problems with Burford House, and indeed with many of the original endowments of the Beauclerk family, was that it was expensive to maintain but generated little income. The 3rd Duke sold it to George III in the 1770s, and it became known as the ‘Garden House’, the residence of the King’s younger daughters. When the Prince Regent (the future George IV) enlarged the Royal Mews, the house was incorporated within the structure and mostly disappeared, though the street that runs past it is still called Saint Albans Street.

The first Duke of Saint Albans (cr. 1684) was also given the office of Master of the Hawks or Master Falconer, which brought with it a pension (about £1,000) and a formal place within the court hierarchy of late Stuart Britain. In the past, this post was not a mere formality, and entailed real duties of supplying hawking birds for the royal sport, acquiring birds and overseeing the officers of the Royal Mews at St Martin in the Fields in London. But the reign of James II was tumultuous and not very much given over to pastimes like falconry, so the teenaged Charles did what many young noblemen did, and sought his fortune abroad. After studying for a spell in France from 1682, he served in the Imperial armies besieging the Turks at Belgrade in 1688—he had a Catholic tutor, and indeed his mother Nell had leaned towards Catholicism, and James II certainly put the pressure on his nephew to convert. But the young Duke did not, and later was a faithful servant of Britain’s Protestant monarchs: indeed, while serving abroad in the Habsburg armies, it is likely he met one or more of the sons of the Duke of Hanover who were also active in the wars against the Turks—the eldest of these would become King George I of Great Britain. Saint Albans also fought for King William III in his overseas wars, notably at the Battle of Neerwinden, east of Brussels, in 1693. He was named Captain of the Band of Gentlemen Pensioners by William in November 1693, a key position of intimacy (the King’s personal escort), and a Gentleman of the Bedchamber in 1697, then continued royal service under George I as Lord Lieutenant of Berkshire (from 1716). His wife was named Mistress of the Robes to Caroline of Ansbach as Princess of Wales.

Lady Diana de Vere was the sole heiress of Aubrey, 20th Earl of Oxford, who died in 1703. The earldom of Oxford was one of the oldest in the realm, dating from the time of the Empress Matilda (1141). Though they did hold properties in Oxfordshire, their main seat and centre of operations was in and around Heddingham Castle in Essex. Even more significantly, the De Veres had been hereditary Grand Chamberlains of England, in almost unbroken line since the 1130s.

By marrying Lady Diana, in 1694, the 1st duke of Saint Albans was emulating his half-brothers who also married great aristocratic heiresses, and usually took on their surname (and in fact subsequent heirs of the Duke would be called De Vere Beauclerk, and added the very simple De Vere pattern to their coat of arms).

But Diana was not in fact a great heiress, as most of the De Vere properties, and the office of Grand Chamberlain, had passed into other families earlier in the century. Compared to his half-brothers, the Duke of St Albans was decidedly poor, with an income of no more than £10,000 by the early 18th century. Nell Gwyn had not been as rapacious as her fellow royal mistresses—recall the “let not poor Nelly starve” story on Charles II’s deathbed. There is the other anecdotal story of Nell being promised and estate ‘as large as she could ride around before breakfast’, which turned out to be quite a bit, and nearly 4,000 acres was given to her just north of the city of Nottingham, on the edges of Sherwood Forest, known as Bestwood. But this estate was too far from court and London society for its first owners, and it lay mostly neglected until the 19th century (and to which we will return, below).

Nevertheless, the 1st Duke and Duchess were prominent members of the court of George I until the Duke’s death in 1726 and hers in 1742. Politically they were Whigs, the main supporters of the Hanoverians, and their family would remain decidedly ‘Whiggish’ for the rest of the century. They left behind a whopping eight sons, all of whom had noteworthy careers, and although most of them obtained offices or military commissions or married heiresses to support themselves (and one became bishop of Hereford), the fact that so many lineages were established right away probably contributed to the swift decline in fortunes of this family, never huge to begin with. In a pattern that would repeat itself again and again across the next two centuries, rich heiresses were found, but long-term wealth always seemed to elude the family, partly because the title continually passing from childless branch to childless branch, and any wealth gained passed out of the family to enrich other dynasties instead.

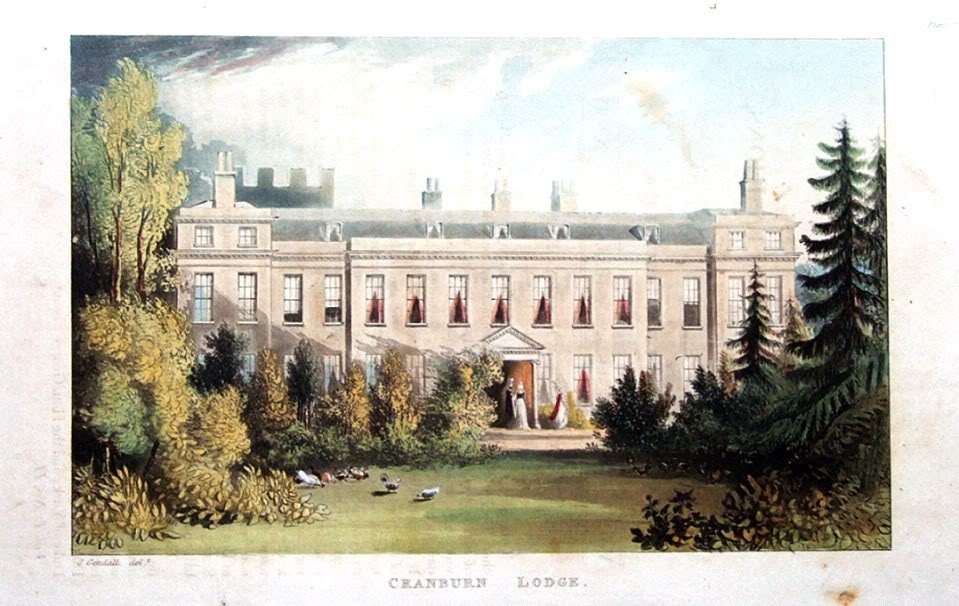

But at least in the second generation, prestigious connections at court kept the family high in the social hierarchy. Charles, the 2nd Duke, was not particularly good at finances, and not a very astute politician, but he was always staunchly anti-Jacobite (never even hinting at support for his Stuart cousin’s royal claims), and was well-liked by George II who confirmed his title (and pension) as Master of the Hawks in 1726, then gave him the prestigious posts of Governor of Windsor Castle and Warden of Windsor Forest in 1730, Lord Lieutenant of Berkshire in 1727, and finally Lord of the Bedchamber in 1738. He did marry an heiress, with estates in Cheshire and Lancashire, but her father outlived him and no money was accrued. Lacking a major country estate, the 2nd Duke was given the grace and favour house, Cranbourne Lodge, in order to carry out his duties in Windsor Forest, and rooms in the Round Tower of Windsor Castle as its governor. Cranbourne, previously the residence of Prince Rupert of the Rhine, had the remains of a Tudor building (a tower, still standing), but had mostly been rebuilt in 1711. The building was last inhabited by Princess Charlotte, daughter of the Prince Regent, and was mostly demolished in the mid-nineteenth century.

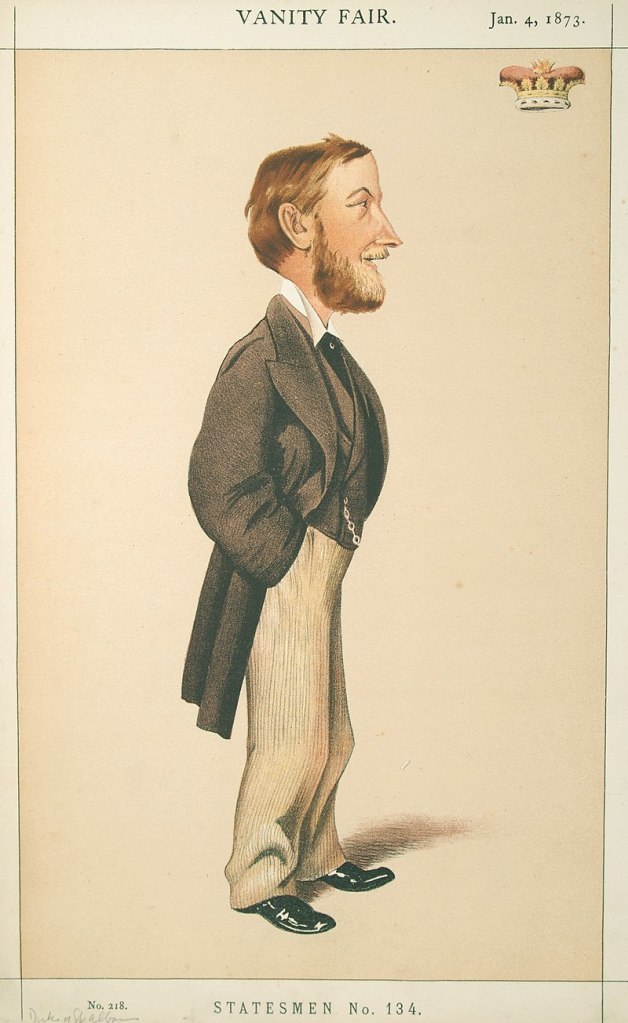

The 2nd Duke’s brothers also held prominent positions in the Royal Household: William was Vice-Chamberlain of the Household of Queen Caroline, 1728-32; Sidney was Vice-Chamberlain of the Household, 1740-42; and George was Aide-de-Camp for the King from 1745 (and would later be commander-in-chief of forces in Scotland, 1756-67). George, the 3rd Duke, would also hold his father’s posts in the reign of George III, but with his death in 1786, much of this close connection ceased, and subsequent dukes were much less intimate with their Hanoverian cousins. Another indication of their decline in social influence can be seen in the wives of the 2nd and 3rd dukes, daughters of baronets, not members of the grand aristocratic houses that dominated 18th-century Britain. Again, the 3rd Duke, George, did marry an heiress, Jane Roberts of Glassenbury Park in Kent, with lands in Surrey and Leicestershire (and a stunningly huge dowry of £125,000!), but the marriage failed and they formally separated—when she died she willed her fortune back to her own cousins. The Duke’s life was chaotic: twice having to flee abroad to avoid creditors, having a child with a dairy maid, carousing in Paris and Venice, losing vast sums of money to fake nobles in casinos abroad. He lived for a time with a mistress and four illegitimate children in a castle outside Brussels, until he was arrested there for unpaid debts and forced to leave by the authorities for ‘indecent living’. He died, childless, a broken man.

The 3rd Duke’s nephew, also named George, held the title for only a year before he died unmarried, age 28, in 1787. He had shown much greater promise: serving in the war in America as a young man, and preparing to inherit a great estate in Cheshire—16,000 acres of rich agricultural land on the fertile Cheshire plain. As he too had no male heir, these estates passed swiftly back out of the family, but took with them some of the Beauclerk art treasures that had been accumulated by the first and second dukes.

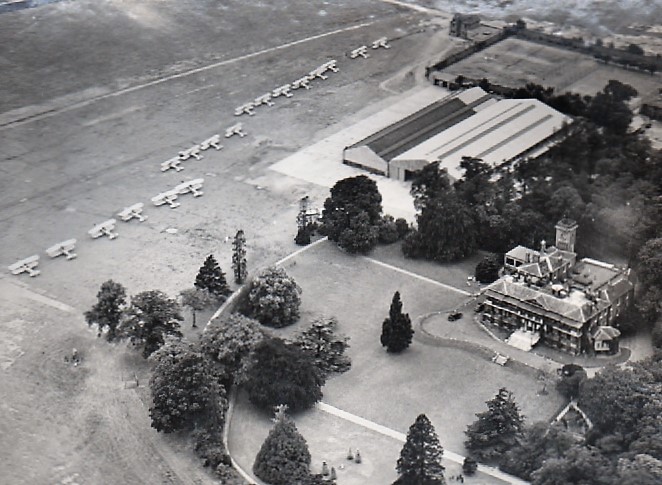

The title therefore passed to a cousin, the 2nd Baron Vere. This cousin, Aubrey (taking one of the names used by the De Veres for many centuries), was the son of Lord Vere Beauclerk, third son of the 1st Duke and Duchess. Lord Vere had a long career in Parliament and in the navy, rising to the rank of admiral in 1745 and Senior Naval Lord in 1746. He was created Baron Vere of Hanworth, Middlesex, in 1750, having married the heiress of Hanworth Park in 1736 (Mary Chambers, whose fortune also included quite a bit of sugar wealth from Jamaica). This grand house, located not far from Heathrow Airport, would therefore become the family seat when Aubrey succeeded as 5th Duke of Saint Albans in 1787. It had been a royal manor in the 16th century, occupied by Anne Boleyn then Catherine Parr, then passed to the family of Baron Cottington, Chancellor of the Exchequer in the 17th century, and then to the Chambers family. It was rebuilt after a fire in 1797, but it is not certain whether this was undertaken by the 5th Duke, or by the next owners (a succession of families). In the 20th century its grounds served as the London Air Park between the wars, but today it and the house lay mostly abandoned.

The 5th Duke was known less as a courtier like his predecessors, but more of a collector. He lived for a time in Rome from the later 1770s, to study and collect art and also to escape the scandal of his wife’s alleged affair—though the alleged lover actually went with them to Italy as well. The Duke financed the excavation of an ancient Roman site, and had himself and his family painted by fashionable Italian artists.

The 5th Duchess, Catherine Ponsonby, was a cousin of the famous Duchess of Devonshire, a woman also known at the time for her scandalous love life. These couples were all part of the beau monde (or the ‘ton’), fashionable aristocrats and socialites. So before continuing on to later dukes, we should pause and look at one of their cousins, one of the most prominent leaders of the ton, with the splendid name of Topham Beauclerk.

Topham was the only child of Lord Sidney Beauclerk, who, as the fifth son of the 1st Duke needed to find a fortune, and he became known as quite the fortune hunter in high society of the 1730s (Lady Mary Wortley Montagu called him ‘Nell Gwyn in person with the sex altered’). In 1736, Lord Sidney did find and marry the heiress Mary Norris, daughter of Thomas Norris of Speke Hall in Lancashire. But a year later, he also received a bequest of the estates of Richard Topham, a bibliophile and collector (especially of drawings) who had become sort of a surrogate father. The Topham estates were located near Windsor (notably Clewer Park), so he now had a residence near his paternal family at Burford House in Windsor, but also an estate and a Tudor manor house far to the north at Speke.

Speke Hall had been built in the 1530s for one of the leading gentry families of the area, the Norrises, who were also noteworthy as one of the most persistently Catholic families of the North (much to the annoyance of Elizabethan authorities). Nevertheless, they were staunch Royalists, and in the Civil War era they converted to Anglicanism and defended the Royalist cause in Merseyside. Today, the house, partly modified by later Victorian owners, is wedged uncomfortably between the outer suburbs of Liverpool and the end of the runway of the local airport, yet the National Trust successfully maintain it as an oasis of tranquillity and historical interest. Lord and Lady Sidney Beauclerk lived at Speke Hall when he was not in London as an MP or attending court as Vice-Chamberlain of the Household—he died in 1744, and Mary lived on as a widow for another twenty years, raising their son Topham, named for his father’s benefactor. Once he was of age, however, he took little interest in Speke, and the property was let out to several people and ultimately sold.

Like many gentlemen of his era, Topham Beauclerk took his Grand Tour, in the 1760s. Back in London he established a reputation as one of the great wits of the age, a close friend of Dr Johnson and a patron of the architect Robert Adam. Johnson seems to have wondered where his much younger friend got his wit and intelligence from, describing his mother Mary Norris as having ‘no notion of a joke…and…a mighty unpliable understanding’, and also lamented as Topham’s failure to actually accomplish anything but engage in brilliant conversation in London society. Yet he loved him dearly, and noted that he would ‘walk to the extent of the diameter of the earth to save Beauclerk’. They caroused together, discussed books together, and founded ‘The Club’ in the 1760s. Topham sometimes hosted this group of intellectuals at the Turk’s Head pub, or at his house on Great Russell Street, where he built a library to house his nearly 30,000 books (languages, sciences, travel books, history, Classics, poetry, and so on). Unlike his cousin the 3rd Duke, Topham had money—he sold a large amount of his estates at Windsor in the 1760s, and there are suggestions that he planned to invest it in redeveloping Speke Hall in the 1770s, though his biographer notes that he lived one generation too soon to become obsessed by the Romantic medievalisms that a half-timbered hall like Speke would inspire. The Hall was instead leased out to local farmers and its precious carved wooden panels in the Great Hall were defaced or broken, and the inlaid oak floors used for firewood. His mother had reputedly wanted him to live at Speke and to assume the name Norris, but he remained in Bloomsbury where he died in 1780, aged only 40. He was described late in life as brilliant but completely idle, even dirty and dishevelled, very disillusioned with society and politics.

At the height of his career as a socialite, however, Topham Beauclerk’s London life was complemented perfectly by his wife. He had begun a relationship with the beautiful Lady Diana Spencer, a daughter of the 3rd Duke of Marlborough, and Lady-in-Waiting to the Queen, whose marriage to Viscount Bolingbroke was falling apart. In 1768, she petitioned for divorce, shocking society, and within two days married Topham (and legitimised their two daughters). Their circle gathered together writers like Edward Gibbon and Horace Walpole, the liberal politician Charles James Fox, and her cousin, the Duchess of Devonshire. ‘Lady Di’ (as she was known) was also a painter herself and Walpole hung several of her drawings at Strawberry Hill and used them as illustrations for one of his plays. After Topham died in 1780, she retired from society and lived on for another twenty years.

Their son, Charles, continued the strong connection with this Enlightened and Whiggish social circle, marrying a daughter of the Duchess of Leinster, a relative of Charles James Fox, and inherited from her the small castle of Ardglass in County Down in Ireland. He was an MP for Richmond in the 1790s, and built a home in West Sussex, Leonardslee, in 1803, to be closer to his work in London. His son Aubrey continued the family tradition of serving as a reformist MP, but his son, William Topham, took this branch of the family in a very different direction, through his marriage in 1910 to Maria de los Dolores (‘Lola’) de Peñalver, 7th Marquesa de Arcos. This title was not claimed by their son, Rafael, but in 1989, he did succeed his mother’s cousin as 6th Marques de Valero de Urría, with its seat in Carreño, in Asturias on the north coast of Spain. Rafael had, during the Second World War, acted as a British military intelligence officer, and his son William also served the British military, as a naval lieutenant on the Queen’s yacht Britannia.

Returning to the main line of the dukes of Saint Albans, the 5th Duke and Duchess—those who had lived in Italy to escape scandal—had several children, including two sons who were dukes, and one who was an admiral. Aubrey, the 6th Duke, was not known for very much, and at first married an heiress (from a formerly Jewish merchant family in Hull), but when she died, her large fortune passed to their only daughter and thus out of the family. He then had a rather quiet second marriage to a daughter of the Manners family (from a junior branch of the dukes of Rutland). Their son Aubrey, succeeded in 1815 as the 7th Duke, at only 4 months old, then he (and his mother) both died six months later. The Hanworth estate (and more of the Beauclerk heirlooms) thus passed out of the family to its natural heirs. The child’s uncle, William, thus became the 8th Duke.

Unlike the other great dukes of the age, neither of the 8th Duke’s two wives came from a grand aristocratic house. But, like his predecessors, his first wife’s inheritance made up for the lack of a great name. Long before he succeeded as duke, Lord William Beauclerk had married Charlotte Carter Thelwall whose family, originally from Denbighshire in Wales, had established a rather large estate at Redbourne in northern Lincolnshire. Already an orphan, Charlotte died soon after their marriage (in 1797) and left her properties to her husband. Redbourne became a lively centre of Lincolnshire society, and Lord William an astute manager of his country estates (one of the few members of this family to do so). Once he became the 8th Duke, he rented a house in Surrey outside London (Upper Gatton), and re-engaged with the court, notably revising the family role as Grand Falconer at the coronation of George IV in 1821. It would seem that the family’s fortunes were finally improving, with a seat now at Redbourne (and a family mausoleum developed in the local village church) and plans already in motion to finally develop the original St Albans estate at Bestwood in neighbouring Nottinghamshire.

The 8th Duke’s son, William, who succeeded as the 9th Duke in 1825, built on this success and married one of the greatest heiresses of any age, but this one from completely different origins—not a typical country gentleman’s daughter. Harriot Mellon had been a Drury Lane actress who first married the Scottish banker Thomas Coutts, age 80, and became established at Holly Lodge, Highgate, then was named his universal legatee (for nearly 1 million pounds) when he died in 1822 (to the annoyance of his daughters from his first marriage). The Widow Coutts then married the much younger 9th Duke of St Albans in 1827, but was snubbed socially at nearly every turn. The royal dukes attended her parties, but their wives and other highborn ladies shunned her, as she had never been ‘presented’ at court. It took a good deal of cajoling to convince an elderly woman to present Harriot, now a duchess, at court, but even after this Queen Adelaide regularly refused to invite her to court functions. Flush with cash, the Duke now made the most of his position as Grand Falconer (which entitled him to a side of venison each year from the Royal Parks), reviving the sport in Lincolnshire and inviting German falconers to come to England. He hosted grand sporting events, dressed in mock Gothic style, in Lincolnshire, but Harriot was not received by the wives of the gentry here either. The couple lived at Holly Lodge or Saint Albans House on Regency Square in Brighton. When the Duchess died in 1837, she left her husband a £10,000 annuity and interests in London properties, but these were for life only, and did not pass to his heirs. Most of her fortune went to her first husband’s grand-daughter (from his first marriage), making Angela Burdett-Coutts one of the great heiresses of the Victorian age.

The children of the 9th Duke came from a second marriage. William, the 10th Duke of Saint Albans, did attempt to carry on his father’s work in re-establishing the family as a grand aristocratic house, notably in the reconstruction of Bestwood as a new ducal seat. The former hunting lodge in Sherwood Forest given by Charles II to Nell Gwyn in the 1680s was entirely rebuilt by the Duke in 1863, and he made it his base for his duties as Lord Lieutenant of Nottinghamshire. The architect, Samuel Sanders Teulon, built a great Neo-Gothic fantasy—quite jarring to some who disliked its proportions, and the fact that much of it looked like a cathedral. It occupies a rise overlooking the city of Nottingham, which end the end spelled its doom, as by the 20th century it was deemed too close to the industrialised Midlands city (with the Beauclerks contributed to themselves, opening a colliery on the Bestwood estate in the 1870s), and the dukes lost interest in the property. It was sold in 1939, and though the house itself survives as a hotel, much of the nicest features of the estate—its woods and terraced gardens—have been redeveloped as the Bestwood Saint Albans business park and surrounding residential neighbourhoods.

The 10th Duke married very well, a daughter of Queen Victoria’s private secretary, General Grey. He became a close friend of the Prince of Wales (who was a witness to the Duke’s wedding in 1867, in the Chapel Royal at St James’s Palace). Royal visitors to Bestwood included the Prince, his brother the Duke of Albany, and his son the Duke of Clarence. In 1874, the Duke married for a second time an heiress of some of the Osborne properties in County Tipperary, including a large estate at Newtown Anner. These new land interests drew him into Irish politics, and he left the Liberals to join the Unionists in 1886. When he died in 1898, the family on the surface looked set to see in the new century, with three sons from two marriages, and daughters married into the very best families (Cavendish, Somerset, Lascelles). But there were already quite dark clouds on the horizon.

Already in the 1890s, his heir, Charles, earl of Burford, was suffering from severe depression. As 11th Duke of Saint Albans he was clearly not well enough to attend the coronations of 1902 or 1911. He was not declared formally ‘insane’, but spent the rest of his life in a clinic in Sussex, until he was succeeded in 1934 by his younger half-brother, Osborne as the 12th Duke. ‘Obby’ was named for his mother’s family in Ireland—the same family, though a different branch, as George Osborne, the Conservative politician. The 12th Duke had been an army officer, an explorer and prospector in British Columbia. He is considered one of the last great eccentrics of the aristocratic age—he wanted to revive the title of Grand Falconer, and specifically, to bring live falcons into Westminster Abbey for the coronation of 1953. He was considered to have great intelligence but little common sense, and his finances—already weakened by his brother’s long period of ill-health—rapidly declined. Obby had married an Irish peer’s daughter (Beatrix Petty-FitzMaurice, daughter of the 5th Marquess of Lansdowne), and lived with her at Newtown Anner, until that property was sold, sometime in the 1940s. Redbourne in Linconshire had already been sold in 1917, and Bestwood in Nottinghamshire, in 1939 (it had in fact already been let out to industrialists since 1915). He spent much of the rest of his long life (he lived to be 90) out of the spotlight, and, having no children, kept his future heirs out of his life, and made no arrangements for a smooth succession (notably employing means to avoid death duties).

The 12th Duke died in 1964 and was succeeded by his cousin, Charles, who thus inherited very little—just the title. He had already had a career as a soldier and a civil servant (notably in military intelligence and propaganda during the Second World War), and now tried to re-establish the family’s fortunes, but made sufficient mistakes such that he had to move to Monaco in the 1970s, and he died in 1988. His wife, Suzanne, was an interesting person: of French descent, she was born on a rubber plantation in Malaya, married Charles Beauclerk shortly after the War, and became a fairly well known writer and painter. The 13th Duke’s heir, Murray, now the 14th Duke of Saint Albans, came from an earlier marriage. He has been the head of the Royal Stuart Society since the 1980s. His son Charles is known as Earl of Burford, and his grandson Baron Vere of Hanworth. The children of the second marriage have a wide and colourful array of marriages to people from across the world, including a bride from Tibet and a groom from the Austrian Habsburgs (Archduke Philipp). Perhaps this new global outlook for the British aristocracy can make up for the lack of firm roots in the countryside, one of the only dukes today without a country seat. What might make the circle complete, however, would be the emergence of a Beauclerk actor or actress, once again recalling the charms of pretty witty Nell Gwyn.

(images from Wikimedia Commons)

One thought on “Dukes of Saint Albans”