It is rare for any aristocratic family to place one of its members so high in the court hierarchy as to be known as ‘the royal favourite’, but for one family to produce two in as many generations, and both with the same name—George Villiers, Duke of Buckingham—is really extraordinary.

Many aristocratic families spend decades rising to the top, and, once achieved, manage to stay there for generations. The Villiers family rose quickly, from provincial gentry to the top of the peerage, then proliferated into a number of different branches, all with titles, and then very nearly petered out altogether. There are only two dukes of Buckingham in the Villiers family, George I and George II. The first features in a new television drama “Mary and George” that portrays the very essence of becoming a royal favourite in early Stuart England, and a cheeky portrayal of the relationship between King James I and one of his greatest male favourites. For the second, a fun portrayal on the small screen can be found in BBC’s “Charles II: the Power and the Passion” from 2003.

There were other dukes of Buckingham. One of the mightiest families of the 15th century, the Staffords, were so titled between 1444 and 1521 when they were cut down by a jealous Henry VIII who feared their Plantagenet blood. Then after the Villiers dukes, the Sheffield family, prominent Yorkshire landowners, were dukes of Buckingham and Normanby from 1703 to 1735. Finally the title was re-created in 1822 for a family who were actually from Buckinghamshire, the Temples of Stowe (though with other inheritances they became the incredibly quintuple-barrelled Temple-Nugent-Brydges-Chandos-Grenville. Their title was extinguished in 1889, and it has not been revived.

Beyond the two Villiers dukes of Buckingham, there were other Villiers royal favourites: one of the most famous royal mistresses in British history, Lady Castlemaine, later Duchess of Cleveland, was born Barbara Villiers. Less well known was her cousin, Elizabeth Villiers, Countess of Orkney, a mistress of William III. Altogether, this is four royal favourites from one family! And there is a fifth…read on!

While the greatest prominence of the Villiers favourites, male and female, diminished by the end of the 17th century, the Villiers family did continue. Overall they obtained four earldoms—Anglesey, Grandison, Jersey and Clarendon—between 1623 and 1776, of which two (Jersey and Clarendon) continue to the present.

To start, the Villiers family appears in records going back to about 1230, as landowners in the area around Brooksby in Leicestershire, the rich agricultural heartland of England’s East Midlands. The claim, as for most English aristocrats, was to be from solidly Norman stock, and certainly ‘de Villiers’ does have a French sound to it (and in fact there are several French noble houses with surnames like Villers, de Ville, or Villars—the latter is a duke’s family, so will get their own blog post), and would mean simply a ‘town dweller’. But it is also possible the name comes from an old Anglo-Saxon word wyler, a trade name for ‘wheelmaker’ (similar to the name Wheeler), and early variants of this family’s name are indeed seen as Vyler. Regardless, they were a solid gentry family for several centuries in the county of Leicester, with a manor house at Brooksby (or Brokesby). The house that is there today was built in the early 17th century, when the family was moving up the social hierarchy. It was extended in the 1890s, and today houses an agricultural college run by the county.

Sir George Villiers (d. 1609) increased his family’s wealth through sheep farming. He served as High Sherriff of Leicestershire in 1591, and as Knight of the Shire for the county in Parliament, 1604-06. He married twice and had two families: the first wife was connected indirectly to the Zouche family, one of the more prominent noble houses of Leicestershire.

Sir George’s second, much younger wife, Mary Beaumont, was a member of the extended Beaumont clan, also prominent in Leicesterhire, but not the same Beaumonts who had governed the county as its earls back in the 12th century. The barons Beaumont came from France to England later, after the Norman Conquest, and one of them married a daughter of the Earl of Lancaster, a Plantagenet, meaning that their descendants had a drop of royal blood. Mary Beaumont Villiers, later Countess of Buckingham in her own right, is the bold character played by Julianne Moore in the new television show.

From Sir George’s first marriage came two sons, William and Edward, who would later give rise to the lines of Villiers baronets and three of the four earldoms. From the second, came three more sons, John, George and Christopher. As the television show demonstrates, it was this second son (actually the fourth overall) who would be the making of this family’s fortunes for the century to come.

Young George was placed at court in August 1614 as a Royal Cupbearer to the still fairly new king of England, James I (James VI of Scotland since the 1560s). Rivals to the King’s current favourite, Robert Carr, Earl of Somerset, saw an opportunity to unseat him by placing in the King’s entourage a young man of 21 who was by all accounts, extremely beautiful and also a pleasant conversationalist and skilled dancer. By 1615, he was a regular feature at court, danced in the court masques before the King, and was promoted to the rank of Gentleman of the Bedchamber. Only a year later he was appointed Master of the Horse, one of the most senior posts at court, and one with a lot of close access to the King as he accompanied him any time he went on procession or hunting. He was named Viscount Villiers in 1616, a Knight of the Garter, and Lord-Lieutenant of Buckinghamshire. Only a year later he was promoted again, as Earl of Buckingham, and again in 1618 as Marquess of Buckingham. A marquisate was still a fairly rare title in England, and James was surely reluctant to promote his favourite to a dukedom since there were at that time *no* dukes in England (Somerset and Norfolk had both been removed and would not be restored until later in the century). So it was a bit of a shock when the King announced in May 1623 that he was creating two dukedoms: one for his cousin (Ludovic Stuart, already Duke of Lennox in Scotland), and one for this favourite, the son of a provincial gentry sheep farmer. George was also named Lord Admiral of the Fleet, 1619, and by 1625, Lord Warden of Cinque Ports, a very lucrative office. His coffers were also enriched by his marriage to the daughter of the 6th Earl of Rutland (see the Manners family here), Lady Katherine, who was in her own right 18th Baroness de Ros, with a seat at Helmsley Castle, in North Yorkshire.

Helmsley was a Norman castle, overlooking the river Rye, and guarded the southern entrance to the Yorkshire Moors. It was held by the Roos or Ros family until 1508, then the Manners until the 6th Earl died in 1632. His seat was at nearby Belvoir Castle, so George and Katherine made Helmsley their seat. Most of the military aspects of the castle were dismantled in the English Civil War of the 1640s, and the rest of it left to decay after a new country house was built next door by new owners in the 18th century.

Meanwhile, George’s brothers were benefitting from his amazing rise. The eldest, Sir William, made a good marriage in 1614 to the daughter of Lord Saye and Sele of Oxfordshire (the same family that much later produced Ralph and Joseph Fiennes), and was given a hereditary baronetcy in 1619, with its seat at Brooksby. He was the Sheriff of Leicestershire and his line maintained the Villiers family’s local influence until its extinction in 1712. Second son Edward was given positions in the government, as Master of the Mint, 1617, and Comptroller of the Court of Wards, 1618. He was later ambassador to the Palatinate and Lord President of Munster, one of the four provinces of Ireland. He married a niece of Oliver, 1st Viscount Grandison who was Lord Deputy (or Viceroy) of Ireland, so their eldest son William inherited lands in Ireland, and succeeded as 2nd Viscount in 1630—this title was in the peerage of Ireland, so it didn’t give him a seat in the English parliament. We will return to him below. Interestingly, of these older half-siblings of the first Duke of Buckingham, Anne Villiers married Sir William Washington, the elder brother of Lawrence Washington, great-great-grandfather of General George Washington.

As for the children of Sir George Villiers’ second marriage, to Mary Beaumont, the eldest, John, was also given prominent positions in the household, as Groom of the Bedchamber and then Master of the Robes, 1616. He was also married to a prominent heiress, Frances Coke, daughter of the Lord Chief Justice, and in 1619 was created Viscount Purbeck (in part to make his new mother-in-law agree to the marriage), and Baron Villiers of Stoke (in Buckinghamshire). It was clear by 1620, however, that he was mentally ill or disabled, and the marriage soon broke down. Viscountess Purbeck was later convicted for adultery. There were no children from the marriage.

Younger brother Christopher (‘Kit’) was created 1st Earl of Anglesey and Baron Villiers of Daventry (in Northamptonshire), also in 1623. Like his brothers, he had been named a Gentleman of the Bedchamber, and took over the role of Master of the Robes from his unfit brother in 1620. Their sister Susan had long been married to William Feilding, another country gentleman, and both of them rose in the court hierarchy as well, created Earl and Countess of Denbigh in 1622. The Countess was soon appointed as a Lady of the Bedchamber to the new wife of King Charles I, Henrietta Maria, and would remain one of the Queen’s closest companions for the rest of her life, accompanying her into exile in France, and even converting to Catholicism (as indeed had done her mother, Mary Beaumont, back in 1620, but that’s another story).

Fetching Henrietta Maria to marry Charles I in 1625 was in fact one of the elements that made the 1st Duke of Buckingham’s name in history—and even in fiction, as his life crossed over into the stories of ‘The Three Musketeers’. By 1623, George was effectively ‘prime minister’ for James I, and, extraordinarily, continued as royal favourite under the new king, Charles I, who succeeded his father in March 1625. Buckingham had grown close to the young Prince of Wales when they travelled together to Spain to attempt to negotiate a marriage with an Infanta; instead they had made the acquaintance of young Princess Henriette-Marie of France when attending a ball in Paris en route to Spain. Their betrothal was announced in December 1624. In the coming years, Buckingham did involve himself frequently in French politics, at first aiding Louis XIII in his war against the Protestants of La Rochelle, then turning around and sending ships and supplies to defend them. He did not however, become the lover of Queen Anne and have to send d’Artagnan racing across northern France to replace her diamonds in order to avoid the menaces of the villain Cardinal Richelieu. In the Dumas book, Milady plots to assassinate the meddling Duke, but is of course foiled.

In reality, the English Parliament was growing increasingly fed up with the Duke of Buckingham’s mismanagement of the war to aid to the French Huguenots, and a botched attempt to capture the rich Spanish port of Cadiz. Parliament had twice attempted to impeach him, but King Charles had rescued him both times by dissolving Parliament. Public opinion was inflamed: the Duke was widely seen as a public enemy. In August 1628, he travelled to Portsmouth to organise another campaign to aid La Rochelle, but was stabbed to death at the Greyhound Inn by a disgruntled army officer.

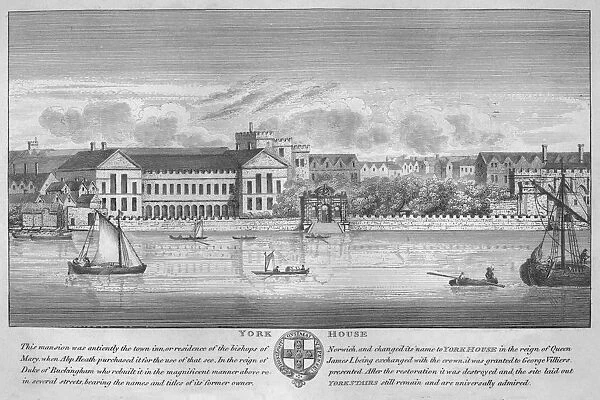

The Duke’s widow Katherine continued to live with their three young children, Mary, George and Francis (born posthumously), at their very grand residence in London: York House. One of the series of large palatial residences on the Strand, with terraced gardens leading down to wharves and docks on the Thames, York House had originally been the London residence of the bishops of Norwich until it was given to the archbishops of York in 1556. After it was given by the King to George Villiers in the 1620s, the new Duke and Duchess of Buckingham embellished its interiors in the fashionable Italianate style of the early reign of Charles I, of which the only remains we can still see today are the very ornate archway to the Watergate the Duke had constructed on the river—now stranded in the middle of Embankment Gardens. This house remained the seat of the 2nd Duke of Buckingham until he sold it in 1672. It was subsequently dismantled, though street names remained to maintain the family’s presence in London, notably Villiers Street, now next to Charing Cross Station.

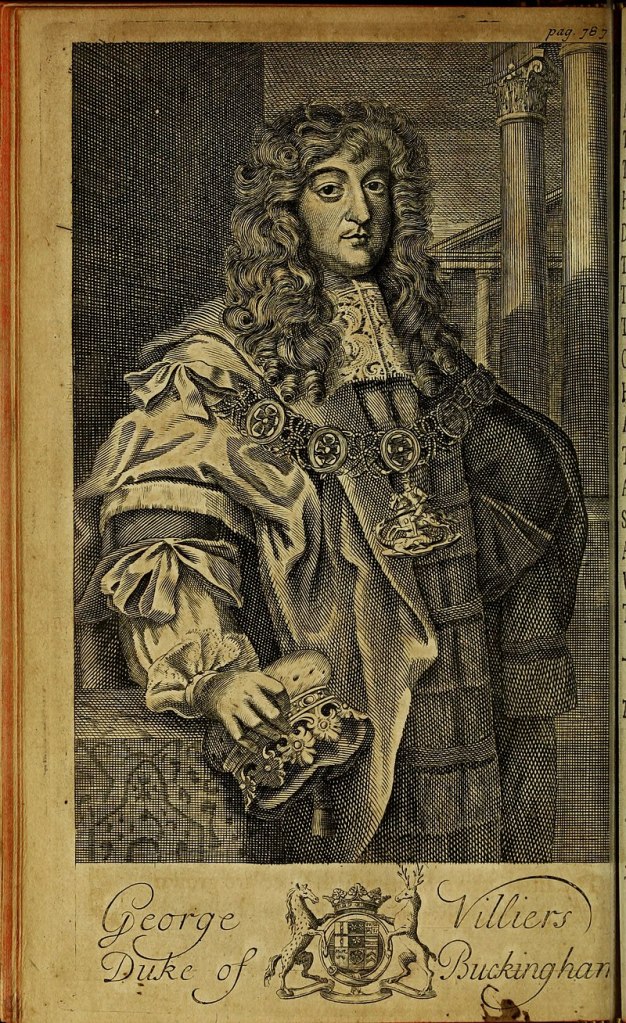

The 2nd Duke of Buckingham, the 2nd George, succeeded to his titles at the age of one. He is certainly one of my favourite people from English history in this period: a fighter, a scientist, a politician, a poet, a dandy and a libertine. He was sometimes King Charles II’s best friend and sometimes his worst enemy. His father having died, and his mother re-marrying and moving to Ireland when he was about 6, George and his brother Francis were taken in by the King and Queen, and raised in the royal nursery with princes Charles and James, only a few years younger.

As a teenager, George fought in the Royalist armies in the English Civil War, then went on tour abroad with his brother. When they returned in 1648, they again joined the fight, and Francis was killed in a skirmish near Kingston in Surrey. George then went into exile with the Prince of Wales in France and the Netherlands, and returned with him for his coronation as Charles II at Scone in Scotland in 1651, and led some of the troops south in the invasion of England. After this failed, he returned with the King to the Netherlands. Here they fell out, over money issues, George’s growing interest in low church Protestantism, and his flirtation with the King’s recently widowed sister, the Princess of Orange. He returned to England in 1657, and, rather strangely, married Mary Fairfax, the daughter of Lord Fairfax, the former commander of Parliamentarian troops and the man to whom his confiscated estates had been given several years before. It seems that George’s move towards low church politics, and Fairfax’s own move towards a reconciliation with the monarchy, met in the middle, and by 1659 both were working for the Restoration.

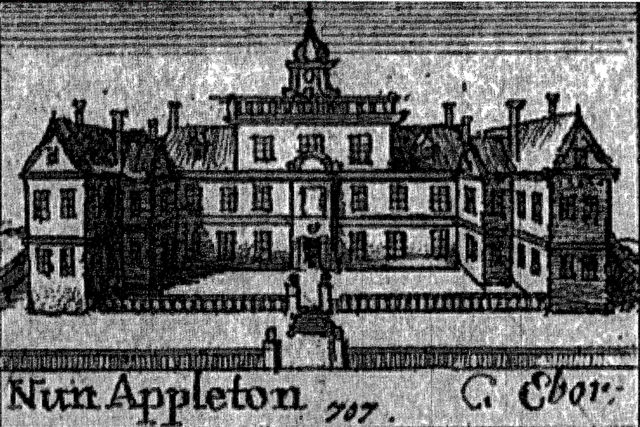

In 1660, Buckingham reconciled with Charles II when he arrived back in England, and was appointed Gentleman of the Bedchamber and Lord Lieutenant of West Riding of Yorkshire, where he and his wife would ultimately inherit the Fairfax properties, including Nun Appleton on the River Wharfe, south of York. Nun Appleton had been a priory from the 12th century, dissolved in the 1530s, and acquired by the Fairfaxes who built a new house in the 17th century. After Mary, Duchess of Buckingham’s death in 1704, the house was sold; replaced by a Georgian mansion, it passed through many hands and now sits decaying and empty—apparently its owner plans to restore it to the original 17th-century design, but is blocked by regulations protecting the later 18th and 19th-century alterations.

https://www.examinerlive.co.uk/news/local-news/gallery/inside-yorkshire-stately-home-abandoned-19146862 [article from 2020]

Anyway, George now became part of Charles II’s ‘Merry Gang’ of drinkers and carousers at the Restoration court. Like his father, he was sent to Paris to participate in another marriage between a Stuart and a Bourbon, this time Henrietta Anne and Philippe, Duke of Orléans (Louis XIV’s brother). But as he had in The Hague, Buckingham seems to have overstepped the mark and flirted too openly with the Princess and was soon sent home. Also like his father, this made it into the Three Musketeers tales of Alexander Dumas (in the Vicomte de Bragelonne). Nevertheless, Buckingham remained close to the French king and a persistent advocate of a French alliance against the Dutch. This put him into opposition to the King’s chief minister, the Earl of Clarendon, who, by 1667, Buckingham was powerful enough to bring down and remove from power. Indeed, from 1667 to 1674, the Duke was now Charles II’s unofficial prime minister, or ‘minister-favourite’, and leader of a faction known as the CABAL—taking its name from its five main leaders, including its ‘arch’ in the middle, B for Buckingham. This clique is considered he kernel of Britain’s first formal political parties, and after its disintegration, one of Buckingham’s former protégés from his now vast Yorkshire patronage network, Lord Danby, would become the next great political leader (Thomas Osborne, later created Duke of Leeds).

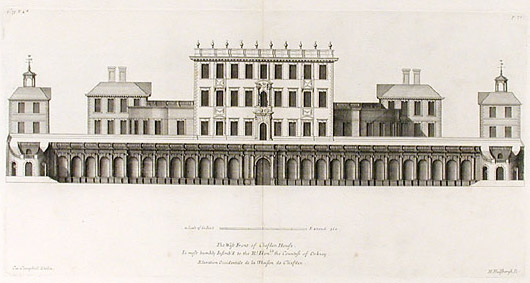

But Buckingham was no great statesman. The only official post he held was Master of the Horse—as above, a position of intimacy and trust with the King—and his ties with absolutist France were increasingly uncomfortable, especially after the Secret Treaty of Dover of 1670 was revealed and seriously embarrassed the King. Despite his pro-French views, the Duke was also vehemently pro-toleration and supportive of the rights of non-conformists—this too put him at odds with the general mood of the populace and the Parliament, and again put the King in a difficult position. Matters were not helped by Buckingham’s personal life: like many noblemen of Charles II’s court, he drank and gambled and duelled, usually over a mistress. In 1668, he duelled with the Earl of Shrewsbury, who was mortally wounded—then installed the now widowed Countess of Shrewsbury as his mistress in his new grand suburban residence, at Cliveden. Cliveden House was built in 1666 on a clifftop (earlier spellings of the house are Cliffden) overlooking the River Thames in Buckinghamshire. It had replaced an older hunting lodge built in the 16th century and was a marvel of grand architecture, a tall pavilion over an arcaded terrace built by William Winde. After the Duke’s death, it was purchased by the Earl of Orkney (whose wife was also a Villers), and in the 18th century was leased to Frederick, Prince of Wales (son of George II), who made it one of his favoured residences. Cliveden burned down in 1795, and the estate lay dormant for some time until the house was rebuilt, on an even grander scale in 1824, then burned down again in 1849, and was rebuilt again in 1851 by the Duke of Sutherland. It then passed to the Duke of Westminster who sold it in 1893 to the Astors who made it one of the most fashionable spots for the beau monde in the early decades of the 20th century. Today the estate belongs to the National Trust, but the house itself is leased to a luxury hotel chain.

In January 1674, Charles II finally acquiesced to demands in Parliament that the Duke of Buckingham be removed from any positions of authority and influence. He was sent away, to live at his Yorkshire estates at Helmsley and Nun Appleton. He began to reform: he attended church, was attentive to his wife, and paid off his debts. Still he meddled in politics, leading a ‘country party’ that was forming in opposition to a more centralist faction in Parliament (the origins of the Whigs and the Tories), and even began making contact directly with Louis XIV over another possible alliance—until he was discovered and threatened with imprisonment in the Tower.

Buckingham distanced himself from the Whigs by about 1680 (due to their insistence on exclusion of Catholics from government), and reconciled with his old friend the King before the latter died in 1685, and before his own death two years later. His wife the Duchess lived on until 1705, but they had no children; nor did his sister Mary, Duchess of Richmond, who also died in 1685. So the Villiers estates were dispersed.

But the age of the Villiers favourites was not quite finished. From 1660 to 1672, the other most dominant person in the life of King Charles II was his mistress Barbara Villiers Palmer, Lady Castlemaine. And following her dismissal, her first cousin Elizabeth Villiers rose to prominence—albeit much less overtly—as a favourite of Charles II’s nephew and (eventual) successor, William III.

Barbara Villiers was the only child of the 2nd Viscount Grandison (above). He died when she was only four, in a battle during the Civil War. The title and estates passed to his brothers, the 3rd and 4th viscounts (founders of later Villiers branches), and young Barbara was left with very little. She was described as one of the most beautiful young women of the age, but had few financial attractions. She did not attract a high-ranking suitor, and in 1659, in seeming desperation, she married a relative nobody, and a Catholic to boot: Roger Palmer, a landowner from the Welsh borders. Barbara and Roger both saw their fortunes tied to a restored monarchy, so went to the Low Countries to meet with the King in the months leading up to the Restoration in Spring 1660. That year he was elected as an MP, and she was selected as the King’s favourite. In 1661, Roger was created Earl of Castlemaine and Baron Limerick (in reference to her father’s Irish titles; and Castle Maine, in County Kerry), which was more mocking than an honour, since an Irish peerage brought no position in England, and the terms of the title’s creation specified that it would pass only to sons born from his marriage to Barbara, not any future wife—in other words, he was an official cuckold, and everyone knew it. The new Countess of Castlemaine was given a position as Lady of the Bedchamber to the new queen, Catherine of Braganza, a humiliation for a pious foreign queen newly arrived and with few friends at this quite anti-Catholic court.

Roger and Barbara legally separated in 1662, in part to avoid his attempts to make claims on the children she was giving birth to. These children were at first called Palmer, but later the King formally recognised them and gave them the name FitzRoy (‘son of the king’). At times this was very confusing: the eldest son Charles was at first known as ‘Lord Limerick’ (Roger Palmer’s courtesy title), and was baptised as a Palmer in a Catholic ceremony, only to be re-baptised later as Charles FitzRoy in a Protestant ceremony. Eventually it was clear these children were royal bastards, and the King gave them increasingly grand titles—all three boys were created dukes: of Southampton and Grafton (both in 1675) and of Northumberland (in 1683). These Stuart dukedoms that descend from Charles II (as with the Duke of Saint Albans, written about previously), will have their own blog posts. Only one of these three ducal lineages founded by Barbara Villiers survives today (Grafton).

By the mid-1660s, Lady Castlemaine was a major figure at court, and with significant influence in government as well. In tandem with her Villiers cousin the 2nd Duke of Buckingham, she brought down the King’s old favourite, the Earl of Clarendon, in 1667. But it was Buckingham who then manoeuvred Nell Gwynne into place as the King’s favourite mistress in the following year, seeing his cousin now as a rival instead of an ally. The King granted Barbara financial privileges and several properties, including Nonsuch Palace, as well as the title Baroness Nonsuch.

Nonsuch was a famous Tudor palace, built by Henry VIII in the 1530s amidst hunting grounds in Surrey, south of Hampton Court. Its name suggested that there was ‘no such place’ equal to it. In the 17th century it had been used as part of Queen Anne of Denmark’s jointure and as a hunting lodge for James I and Charles I, and finally as a residence for the Queen Mother, Henrietta Maria, during the Restoration. In a great act of cultural vandalism, Barbara ordered the palace’s dismantling in 1682, and its parts were sold to pay off her mounting debts. Nothing remains.

Barbara Villiers was also created Duchess of Cleveland in her own right in 1670, with the letters patent specifying it would pass to her eldest son, Charles FitzRoy. Cleveland took its name from the region of high peaks (cliffs or ‘cleves’) and dales in north Yorkshire. There had been an earl of Cleveland (Thomas, 4th Baron Wentworth), who was part of the clientele network of the 1st Duke of Buckingham, and his son a close companion of Charles II in exile. The Earl died in 1667 and perhaps the King wished to remember him and his earlier Villiers connections in re-using the title for Barbara in 1670.

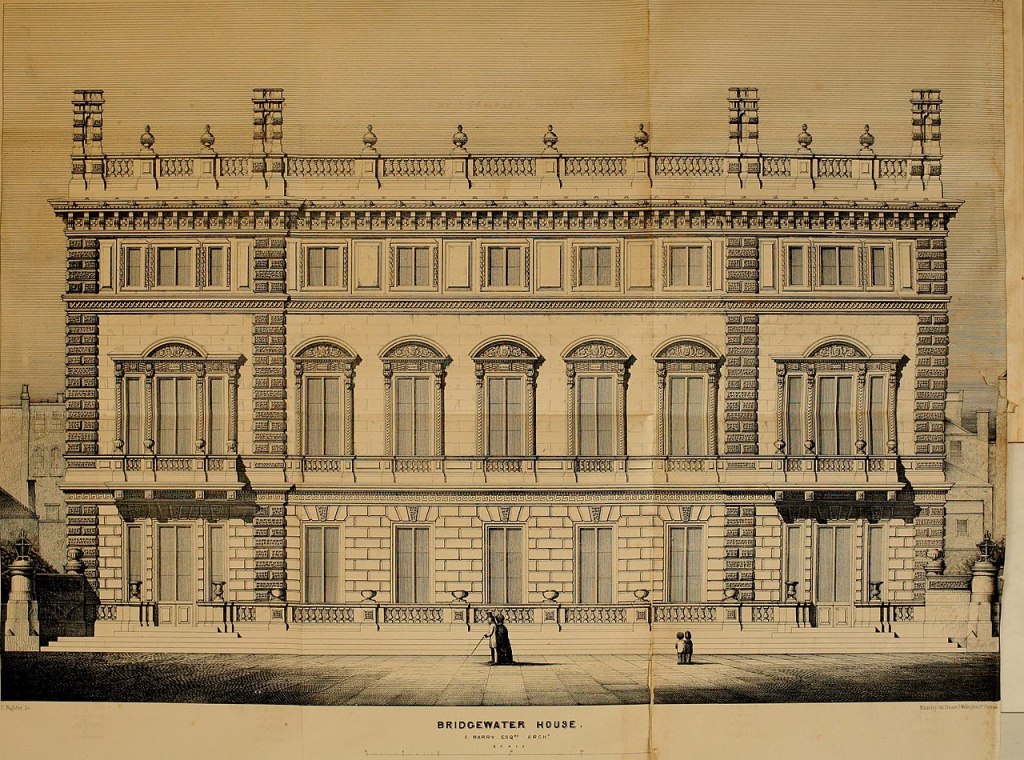

The name was also given to her London house, which she acquired from Clarendon’s fall in 1667. Cleveland House, directly behind St. James’s Palace and overlooking Green Park in Westminster, had been built for the Earl of Berkshire (a Howard) in the 1620s, then was the residence of the Earl of Clarendon as First Minister in the 1660s. Barbara expanded and refaced it in the 1670s, but before she died, she sold it to the Egertons, later dukes of Bridgewater. Since then it has been called Bridgewater House, but the address is still Cleveland Row. It was rebuilt in the 1850s, then sold off after World War II—it was used for offices until the 1980s when it once again became a private residence.

By about 1672, it was clear that Charles II’s favourites were Nell Gwynne and the newly arrived Louise de Kérouaille. The Duchess of Cleveland lost her position as Lady of the Queen’s Bedchamber due to the Test Act of 1673, since she was a Catholic (having converted back in 1663), and the King sent her away from court. She lived in Paris, 1676-80, then was briefly reconciled with the King before he died in 1685. Her life after that was rather sad, with increasing penury and foolish romantic liaisons, culminating in a marriage of 1705 to Major-General Robert ‘Beau’ Fielding, whom she later had to prosecute for bigamy once she discovered he was already married. She lived her last years in a large brick house in the western London suburb of Chiswick—this ‘Cleveland House’ was later renamed Walpole House for its 18th-century owner, and hosted a prominent school in the 19th century, before being restored as a private house again in the 20th.

Barbara died in 1709. Her long forgotten husband, Roger Palmer, Earl of Castlemaine, had actually risen in favour after the death of Charles II, since, as a Catholic, he was esteemed by the new king, James II. He was named to the Privy Council in 1686, and sent as Ambassador to Rome. After James’ fall, of course, this brief prominence faded, and Castlemaine spent the rest of his life either as a Catholic suspect in the Tower of London, or on his estates on the Welsh borders where he died in 1705. The dukedom of Cleveland passed to Barbara’s son Charles, Duke of Southampton, and to his son, William FitzRoy, who died in 1774. The title was re-created in 1833 for his grand-nephew, William Vane, Earl of Darlington (and so continued until its extinction again in 1891).

As Barbara Villiers’ star was fading, her cousin Elizabeth’s was rising. Her father, Edward, was the youngest brother of the Viscount Grandison (Barbara’s father), and her mother was Lady Frances Howard, daughter of the Earl of Suffolk. Like all of the family, he was a staunch Royalist and went with Charles II into exile in 1649. During the Restoration, his wife was appointed governess to the King’s nieces, princesses Mary and Anne of York. So when Princess Mary was sent to the Netherlands in 1677 to wed her first cousin, William, Prince of Orange, she was accompanied by some of Sir Edward and Lady Frances Villiers’ daughters, including Elizabeth, to serve as her maids of honour in her court at The Hague. It is uncertain when (or even really if) Elizabeth became a mistress of Mary’s husband William, whose affairs with men were becoming fairly well known, especially his primary favourite, Hans Willem Bentinck (who, incidentally, married Elizabeth’s sister, Anne). When William and Mary became joint King and Queen of England, Scotland and Ireland, Elizabeth Villiers returned to England, and continued to act as a royal favourite—perhaps a ‘beard’ for the King’s relationship with Bentinck? It seems that, after Mary II died in December 1694, William was committed to ‘cleaning house’ to honour his late wife’s memory, and dismissed Elizabeth by rewarding her (a quite traditional way of signalling the end of a royal relationship): he granted her extensive lands in Ireland in 1695 and married her off to one of his military lieutenants, Lord George Hamilton (a younger son of the Duke of Hamilton); the following year they were created Earl and Countess of Orkney. This is the same Orkney who purchased the palatial Cliveden House (above), and so it was yet another Villiers who played grand hostess there in the early Hanoverian era of the 1710s-1720s. She died in 1733, leaving her estates to daughters.

The Villiers legacy therefore was carried on by Elizabeth’s brother, Edward. He too was in King William’s favour, and was named Viscount Villiers in 1691, then Earl of Jersey in 1697. He was Master of the Horse to Queen Mary, then Lord Chamberlain to King William. He was sent as Ambassador to The Hague and Paris in the 1690s, crucially representing England at the treaty negotiations at Rijswijk in 1697. He was named one of the King’s secretaries of state in 1699, but didn’t survive long after the King’s death in 1702—Queen Anne dismissing him from all of his posts in 1704. Perhaps this last of the Stuarts had finally had enough of the Villiers family…

The Villiers family in the 18th century were thus represented by the last Viscount Grandison (John) who was created Earl Grandison in 1721 (still in the Irish peerage) and given a seat on the Irish Privy Council. When he died in 1766, this branch ended in the male line—the earldom of Grandison was re-created for his daughter and grandson (George Mason, who took the name Villiers in 1771), and the viscountcy passed to his cousin the 3rd Earl of Jersey. This 3rd Earl (William), had built a new county seat at Middleton Stoney, located in the rolling green hills just west of Bicester in Oxfordshire. Middleton Park remained the Jersey seat, rebuilt in the 1930s by the 9th Earl, until it was developed as apartments in the 1970s.

Of subsequent earls of Jersey, the 5th Earl (d. 1859) stands out as a prominent Tory politician in the reigns of William IV and Victoria, as Lord Chamberlain in the 1830s and Master of the Horse in the 1840s (and briefly again in 1852). He added his wife’s mother’s surname, Child, to Villiers in 1819, as heiress of the vast wealth of the Child Bank, and their grand house, Osterley Park, in the western suburbs of London. The 6th Earl married a daughter of Prime Minister Robert Peel, but was only earl for 21 days, before he followed his father to the grave. The 7th Earl of Jersey was Governor of New South Wales in Australia (1890-93), while the 8th Earl re-trenched in the 1920s by selling the Child Bank. Today’s earl, the 10th, is William Child Villiers (b. 1976), whose family home is actually on the island of Jersey (Radier Manor). His heir, Viscount Villiers, is appropriately named called George.

As for the extant junior line, the line of earls of Clarendon (a seemingly ironic title, given the family’s concerted efforts to bring down the great Lord Clarendon in 1667), was founded by Thomas Villiers, second son of the 2nd Earl of Jersey. He was a diplomat, sent to Warsaw, Vienna and Berlin in the 1740s, then a Whig MP (in contrast to his mostly Tory family) in the 1750s-60s, and joining the Government as a member of the Privy Council and Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster in the 1770s-80s. In 1752, he married Charlotte Capel, daughter of Jane Hyde, the heiress of Henry Hyde, 4th Earl of Clarendon. Thomas Villiers was thus created Baron Hyde (of Hindon, Wilts.) in 1756, and later Earl of Clarendon in 1776. He built a new family seat, The Grove, near Watford in Hertfordshire (which, like so many of these grand country houses, is now a luxury hotel).

Of the later earls of Clarendon, the 4th Earl (George Villiers, d. 1870), was the ‘Great Lord Clarendon’, a prominent diplomat and Liberal politician in the reign of Queen Victoria: three times Foreign Secretary, Lord Privy Seal, and like his grandfather the 1st Earl, Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster. He also renewed some of his family’s old links with Ireland by serving as Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, 1847-52. In the 20th century, the 6th Earl of Clarendon was Governor-General of South Africa, 1931-37. Today’s 8th Earl (b. 1976) has a son, Edward, known as Lord Hyde.

There was one last royal favourite connected to the Villiers family: Frances Twysden (1753-1821). No stranger to scandal from the moment of her birth, she had been born posthumously to the Right Reverend Philip Twysden (from a Kent family), who, despite being Bishop of Raphoe in the Church of Ireland, was shot dead in 1752 while (allegedly) attempting to rob a stagecoach near London. Just over 17 years later, Frances married George Villiers, 4th Earl of Jersey (d. 1805), a Gentleman of the Bedchamber to King George III. In about 1793, Lady Jersey became the mistress of George, Prince of Wales; in 1794 she was appointed Lady in Waiting to the new Princess of Wales (Caroline of Brunswick), and her husband was subsequently appointed the Prince’s Master of the Horse, making them quite a power couple for—as it was anticipated—the reign soon to come. But George III, though he went mad, did not die until long after Lady Jersey had lost favour, in 1807, when she was dismissed as Lady of the Bedchamber. As fate would have it, there would be no great Villiers royal favourite for this particular royal (this time with the name George) when he became king in 1820.

(images Wikimedia Commons)