The Baltic states of Estonia and Latvia were long dominated by German nobles who settled in the wake of conversion crusades led by military orders in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. Over the centuries that followed, they formed a fairly closed set of families, intermarrying and retaining their authority over the local native populations (Estonians, Letts, Semigallians, etc), and occasionally rising to greater power and rank due to service to foreign powers like Russia, Sweden, or Poland-Lithuania. Eventually they lost their dominant position following the first World War, and most were then expelled completely following the second World War and Soviet occupation of the region.

One family amongst these did claim to have local Baltic rather than German roots, though this may have just been family mythology. In the 1260s, a certain Gert Live (Gerhardus Lyvonis) appears in the records as a vassal of the Archbishop of Riga (today’s capital city of Latvia). The family story was that Gert was a descendant of a local chieftain of the Letts, also called Livs or Livonians, Kaupo, who converted to Christianity in 1186, and travelled to Rome in 1203 to gain support for his position as an independent prince or quasi-king and for the conversion of the Livonian people. The surname Lieven ultimately is said to derive from Live, or ‘the Livonian’. An independent Livonian state run by its own Livonian Brotherhood did not survive very long, however, and by the 1230s was subject to the Teutonic Order who constructed their own Baltic state called Terra Mariana.

Several generations later, Gert’s descendant Hincke or Heinrich exchanged his lands in Livonia for some further north, in the diocese of Ösel-Wiek, in what is now the western parts of Estonia. This semi-independent diocese is known in Estonian as Saare-Lääne, formed of the island of Saaremaa and the mainland county of Lääne (which means ‘western land’). The new family base was the manor of Parmel, which today is called Liivi—I’m uncertain if the family took its name from this manor or the other way round (it is also the name of the local river). From the 1380s there was a stone fort at Parmel; Heinrich’s family held this manor until 1694 and there are still remnants of the stone building today.

In the fifteenth century the family split into its two main branches: the line of Jürgen of Parmel stayed in the north and ultimately became prominent in Swedish affairs, and rose to the rank of count in the 18th century; while the line of Johan moved south into what is now Latvia and formed what is called the Courland branch, who ultimately entered Russian service and became princes in the 19th century—hence the family’s inclusion in this website.

So we need first to look at the growth of the Swedish Baltic empire. In the 1560s, Jürgen’s son Heinrich sided with a Danish prince, Duke Magnus, who was attempting to erect the northern parts of Estonia and Livonia into an independent kingdom (with Russian support). Magnus was attacked by a coalition of Polish and Swedish forces (the ‘Livonian War’) and ultimately chased out. Sweden took over these territories and Heinrich Live was taken as prisoner to Sweden, his possessions confiscated. The northern parts of the former Terra Mariana became Swedish Estonia, while the southern parts became (eventually) Swedish Livonia. The Swedish Crown would govern these territories—with not insignificant impact on Sweden itself, since Riga was the second largest city in its empire after Stockholm—until they were conquered by the Russians in 1721.

In 1582, Heinrich Live’s son Reinhold swore an oath of loyalty to the Swedish king and regained his father’s lands in Swedish Estonia. He was appointed a noble deputy to the Estonian Landrad (the local estates) in 1599, and became a colonel in the Estonian contingent of the Swedish army. His son, Bernhard, was also part of the Swedish government in Estonia, and married a woman from another local Baltic family (with the wonderful name of Yxkull, or Üxküll), but his grandsons began to integrate more fully into the Swedish court nobility.

Reinhold, who began to use the surname von Liewen (or Liven) was a Captain in the Swedish Royal Life Guards, 1645, and in 1653 was created a baron by Queen Christina, with lands centred on the city of Eksjö in the Swedish county of Småland. Småland is a large but mostly rural province on Sweden’s southeast coast. It was not the richest province in the realm, but Eksjö was conveniently located on trade routes between the north and the south, and the coast and the interior. Eksjö was one of the few territorial baronies to exist in the Kingdom of Sweden—most were simply tied to the family name.

In 1654, Reinhold von Liewen was sent back across the Baltic: he was governor of the island of Ösel and its chief fortress Arensburg Castle (Kuressaare in Estonian). He acquired more lands in Estonia in the parish of Rötel (Ridala in Estonian), not far from their ancestral lands, notably Weissenfeld, or Valgevälja (‘white field’ in Estonian), which also became known as Kiltsi manor (after the name of its former owners). The old castle there had been rebuilt in a Renaissance style in the early 17th century; today only ruins remain.

His younger brother Bernhard Otto was also created a Swedish baron in 1653, and also expanded landholdings in Estonia, at Raggafer (Rägavere) further inland, southeast of the capital of Reval (today’s Tallinn). In the 1660s he led the Estonian noble company in the Swedish army and in 1673 was named colonel of the Turku County cavalry regiment—Turku is in southwestern Finland and was an important base of operations for the Swedish empire of the Baltic, of which the Liewens were now at the very centre. He and his older brother formed the two main branches of this now baronial family, the ‘Black Liewen’ and the ‘White Liewen’.

The senior line, ‘Black Liewen’ served at court and in the military, and acquired more lands in Sweden, notably Vik and Bärby in Uppsala County). These were acquired by Baron Bernhard von Liewen, a soldier who had gained experience abroad in France and the Dutch Republic, then returned to Sweden to emerge as a hero in the 1670s war defending Scania against the armies of Denmark. When war broke out between Sweden and Russia, King Charles XII took Baron Liewen with him to Livonia to help him navigate the territory, but he was killed in battle soon after, in 1703.

Vik Castle had been built by the powerful Bielke family in the 15th century, and is considered by many to be the best preserved medieval castle in all of Sweden. Located on the shores of a picturesque lake south of the city of Uppsala, Vik was renovated in a more ‘French’ style in the 17th century, and again by later owners in the 19th century. The Liewens acquired it through marriage to an heiress in 1689; in 1809 it passed by another marriage to the Essen family who owned it until 1912 when they sold it to a banker, who then sold it in 1923 to the local county government—today the county runs it as a conference centre.

This branch of the family also continued to maintain its presence in other parts of the Swedish empire, as commanders of the Estonian regiments of the Swedish army, or as governors of military garrison towns in the newer Swedish provinces in northern Germany, such as Wismar in Pomerania. By the end of the 17th century they were marrying noblewomen with surnames from the highest Swedish nobility—Oxenstierna, Bonde, Brahe—and were now being buried in Stockholm, not Reval.

This branch moved more closely into the favour of the royal house in the early 18th century: Baron Carl Gustaf of Vik was named Chamberlain to Duke Carl Friedrich of Holstein-Gottorp, whose mother, Hedvig Sophia of Sweden, was for a time heir to the Swedish throne. Ultimately the Holstein-Gottorp family succeeded to the throne, from 1751, and the von Liewen family benefitted. Carl Gustaf’s widow, Ulrike Juliane Brahe, became Chief Mistress of the Court in 1762, while her son Carl Gustaf II was Marshal of the Court from 1759. Carl Gustaf II had been a chamberlain since the 1740s, and a gentleman in waiting in 1751. The next year, the new king, Adolf Frederick, appointed him a caretaker, as ‘knight of honour’, of his second son, Prince Carl (born 1748, who would later become King Carl XIII). Carl Gustaf was also sent on diplomatic missions, to Hesse and to Russia, and ended his career as Governor of Stockholm County in 1768.

The most prominent member of this branch at the Swedish court was Carl Gustaf’s daughter, Ulrika Elisabet, known as ‘Ulla’, who was a Maid of Honour to Queen Lovisa Ulrika from 1764, but became the favourite, and (probable?) mistress, of her husband, King Adolf Frederick. They are rumoured to have had a daughter together, but this is not certain. Perhaps more importantly, she became a well-known leader of an intellectual salon in Stockholm, and was involved in the liberal politics of the reign of King Gustav III, but died relatively young in 1775.

Her brother, Carl Gustaf III, first spend some time commanding the Royal Suédois Regiment in France in the early 1770s, at a time when Sweden and France were renewing friendly ties (against mutual foe Prussia), but returned to be Chamberlain to the Dowager Queen Lovisa Ulrika and then Colonel of the Regiment of Life Guards. He ended his days as a Lieutenant-General and President of the Military Court. When he died in 1809, this branch of the family ended.

The junior branch in Sweden, the ‘White Liewen’ had a much broader spread, with many sons and grandsons forming sub-branches of their own. There were numerous commanders and generals in Swedish service but also in Austrian, French or even Spanish service. Several commanded the Turku regiment in southwest Finland, and there were also a number of commanders of the military fortress at Landskrona in western Scania, built by the Danes in the 16th century to help control water traffic through the Øresund, which separates Scania from the rest of Denmark (Scania became Swedish only after 1658). The Liewens also acquired property in this southern region, for example Lärkesholm a bit further inland (in the northern part of Kristianstad County). As a now more ‘southern’ Swedish family, they frequently commanded the regiment of the County of Kronoberg, just north of Scania in the province of Småland (thus closer to their barony of Eksjö), and they acquired lands in this county too (Malteshom, Silkesnäs).

Of all of these, one branch stood out, founded by Hans Henrik von Liewen, who was a successful military commander, rising to the rank of lieutenant-general in 1714, He was rewarded by being elevated to the rank of count in 1719, and a Councillor of State. Much of this was in recognition of the confidence he gained with the king, Charles XII, when in 1713 he journeyed to the Ottoman Empire to try to convince the warrior king to return to Sweden following his huge defeat by the Russians at Poltava in 1709. Instead he joined the King in his self-imposed exile and built up a friendship; when they both returned Hans Henrik was put in charge of re-constructing Sweden’s navy from its main base at Karlskrona. King Charles died in 1718, so it was actually his sister Queen Ulrika Eleonora who granted the new elevated title. The first Count von Liewen died as a respected member of the Swedish court in 1733.

Both of his sons were prominent in the Swedish army in the decades that followed, but the eldest, Count Hans Henrik ‘the younger’ brought the entire clan to its greatest heights so far. From the mid-1740s he was part of the inner circle of Duke Adolf Frederick of Holstein-Gottorp, who had been elected as heir to the Swedish throne, so when Adolf Frederick became king in 1751, Count von Liewen was favoured. His sister, Henrika Juliana, also became a court favourite, as a maid of honour to the new Crown Princess, Louisa Ulrika of Prussia, and one of her chief confidantes. The six maids of honour of the Crown Princess were known for their beauty and intelligence, and were painted in a curious ‘hen picture’ (Hönstavlan) by Johan Pasch in 1747, with the playful caption: ‘Who is the cursed rooster that would not crow, Hens, in seeing your features and your charms?’ But in 1748, this close confidence with the Crown Princess was apparently broken, and Henrika Juliana is believed to have been the informant that exposed a coup she had planned against those Swedes who wished to limit the power of the monarchy. Later in 1748, Henrika Juliana married and left the court, but she remained politically active, in the ‘Hats’ party who advocated a strong parliament dominated by the nobles, and thus a weak king. She is credited with editing the party’s provocative pamphlet, En ärlig Swensk (‘An Honest Swede’), published in 1755-56, and subsequently denounced by the King in the parliament.

Her brother Count Hans Henrik retained royal favour, however, and that same year was promoted to the rank of Lieutenant-General. In 1759 he was sent as Ambassador to Russia, where Adolf Frederick’s nephew, Grand Duke Peter, was preparing to take over as Tsar as heir to Empress Elizabeth. Back in Sweden, Hans Henrik was appointed a Privy Councillor in 1760, then Governor-General of Swedish Pomerania, on the northern coast of Germany, in 1766. He governed there until 1772, then returned to take up a post as Chief Marshal of the Court and Marshal of the Realm for his old friend’s son, now King Gustav III. When he died in 1781, the title of count died too.

The other, still baronial, branches continued, but declined in prominence in the nineteenth century. Baron Frederik (d. 1875) was a merchant in Linköping, while his cousin Jakob Vilhelm (d. 1858) became a captain in the merchant navy. His grandson, Baron Christian von Liewen, was a sea captain who founded a shipping company in Helsingborg. When he died in 1917, the Swedish branches of the House of Liewen came to an end.

And so we must jump back across the Baltic to Livonia. The branch that was established by Johan Live back in the early 16th century acquired lands in a region known as Vidzeme, today the northern part of Latvia. In 1533 they founded a new town a bit further to the south, in lands governed by the archbishops of Riga, which they named Lievenhof in German (today called Līvāni). In 1631 they were formally admitted into the nobility of Courland (Kurzeme in Latvian), an independent duchy founded in the 1560s by the last Grand Master of the Livonian Order, Gotthard Kettler. This territory, now the far western part of modern Latvia, was nominally a vassal of the Kingdom of Poland-Lithuania, but increasingly came under Russian influence in the 17th and 18th centuries.

In the early eighteenth century, the seat of the family in Courland (now called ‘von Liven’ or ‘Leeuwen’) at was Bersen manor (Bērze in Latvian, or Lieven-Bersen, today called Līvbērze), which had a long grand frontage and a prominent gateway tower that became a symbol of the locality. The gateway and its tower were destroyed by the Soviets when they needed clearer access to the farm after nationalisation, but since 2020 there has been an exciting burst here of archaeology and regeneration of the house and its estate (referred to as ‘Live Manor’).

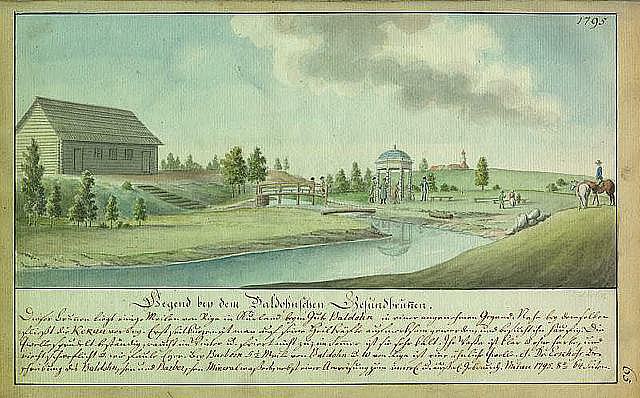

Another grand manorhouse built in Courland in the mid-18th century was Dünhof (also called Livens Manor), now Daugmale, on the banks of the Daugava River before it flows into the city of Riga. A few miles away was Baldone Manor (Baldohn), acquired by the family in 1750. Friedrich Georg von Liven (d. 1800) was a Russian army officer who retired to this estate to beautify its parks and gardens, and to establish a resort in its sulphur springs. This resort remained quite popular well into the 20th century, but declined in the 1930s and is now mostly a ruin.

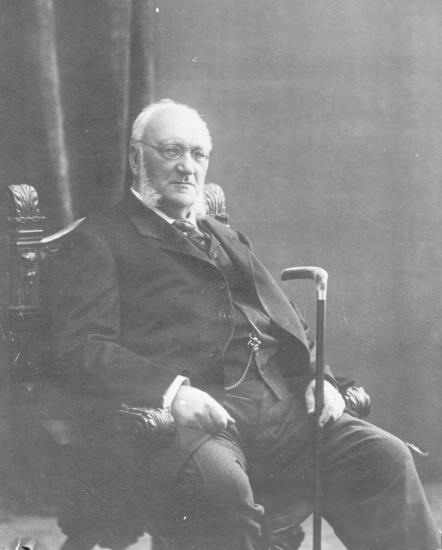

When Courland was incorporated into Russia formally in 1801, the head of this branch of the family (Georg Philipp, d. 1847) was given the title of Count of the Russian Empire. His son, Count Wilhelm Heinrich, born at Dünhof in 1800, made his name as head of the Imperial Division of War Topographers in the 1850s, then was promoted to the highest position back in Livonia, as Governor-General of the Baltic Provinces, based in Riga, from 1861 to 1864, and a member of the Imperial Council of State.

But another line of the Courland branch of the von Lieven family rose even higher than the rank of count: the Princes Lieven.

In 1766, a major-general in the Russian army, Baron Otto Heinrich von Lieven, married Baroness Charlotte von Gaugreben. Her family were not originally Baltic Germans, but Westphalian nobles, but one branch (a Catholic branch) had emigrated eastwards to establish themselves in Russian service. Two years after she became a widow in 1781, Charlotte was appointed as governess of the daughters of Grand Duke Paul, son and heir of Empress Catherine II. Her charge was later expanded to include Paul’s younger sons, Grand Duke Nicolas and Grand Duke Michael. Her influence at the court grew as these royal children matured, and formed a bond between the two families that would last generations.

In 1794, Charlotte von Lieven was named a lady-in-waiting to Catherine the Great in her last years. In 1799, in the new reign of Emperor Paul I, she and her children were promoted to the rank of Count of the Russian Empire. After the death of Paul I in Spring 1801, the new Emperor (Alexander I) promoted her further, appointing her Mistress of the Household of his wife, Empress Elizabeth Alexeievna. Finally, in 1826, after her former pupil Nicolas had succeeded his brother as Emperor of Russia, she was given the highest honour, princely rank, which was extended to her children as well. She died in 1828 in her apartments in the Winter Palace in Saint Petersburg.

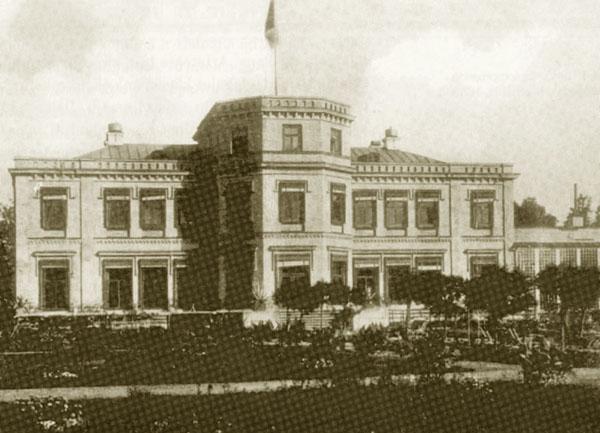

Catherine the Great had also provided the faithful Charlotte von Lieven the use of a grand estate back in Courland, Mesothen (Mežotne in Latvian). Located on a broad bend of the river Lielupe in southern Semigallia, due south of Riga (now near the border with Lithuania), this grand neoclassical building was completely rebuilt from 1797 when Paul I rewarded Charlotte for her past services to his children by granting ownership outright. He also gave her the estate of Tersa on the Volga in the Saratov District; and later she was given more lands in Russia itself, including Baki in the Kostroma district, also on the Volga but much further north, and still more estates back in Courland. By this point Mesothen was a grand palace (its old manor house now became the caretaker’s house), with extensive gardens. The family resided here until 1920, when the new Republic of Latvia nationalised most large estates in a sweeping agrarian reform movement. An agricultural school was established in the 1920s, which persisted in various forms until the 1990s, when it was transferred into the ownership of the state heritage bureau, and in 2001 was opened as a hotel,

Princess Lieven had four sons and two daughters. Three of the sons married and founded separate lineages of this now Balto-Russian princely house. The eldest son, Carl Christoph, who in 1828 became the 2nd Prince Lieven (the Russians tended to delete the ‘von’), was at first a keen soldier. At 21 he was an aide-de-camp of General Potemkin, and by 1799 was a lieutenant-general and commander of the elite Preobrazhensky Regiment. After the turn of the century, he turned more towards religion and in particular evangelical pietism. He worked to develop the newly re-founded University of Dorpat (today’s Tartu, in Estonia), supporting the adoption of courses in medicine and the natural sciences in particular. Years later he was given an honorary seat in the Russian Academy of Sciences. But in terms of religion, he was one of the founders of the Russian Evangelical Bible Society and President of the Evangelical Lutheran General Consistory, from 1819 to 1821. But in 1826, along with his elevation to princely rank, he was recalled to imperial service in Saint Petersburg, with a seat on the Council of State and a role in the Supreme Criminal Court. In 1828 he was appointed Minister of Education, an interesting nod to his earlier work in the Baltic, but also to his mother’s role as educator of children of the imperial family. In 1833, Carl Christoph retired back to his estates in Courland. He died in 1844 having married twice, both times to daughters of the Baltic German nobility, and fathering five children, whose stories will be picked up below.

The 2nd Prince’s brother, Prince Christoph Heinrich, was a respected ambassador, first in Berlin then in London, and a participant at the famous Congress of Vienna, 1814-15. But it was his wife, the former Dorothea von Benckendorff, who left a bigger impression in history—in fact, she was one of the most well-known women of her century. The Benckendorffs were a baronial family from the Altmark in Brandenburg, who had moved to Riga in the mid-sixteenth century. Dorothea’s father was a Russian general and Imperial Governor of Livonia. Her mother was Senior Lady-in-Waiting to the Empress Maria Feodorovna (wife of Emperor Paul), and in 1800, the 17-year-old Dorothea was named one of her maids-of-honour. She soon married Christoph von Lieven, and in 1810 he was appointed Ambassador to Berlin, so she accompanied him there, then on to London in 1812. It was here that Princess Lieven (as she was known after 1826) thrived. She became a leader of London’s political and social world, a close friend and confidante to leading statesmen including Lord Castlereagh, Lord Grey, the Duke of Wellington and the Prince of Wales (the future George IV). She is reputed to have had more intimate relations with Lord Palmerston, and even with Metternich, but this may just be gossip. The truth was certainly that by the 1820s people were clamouring to get invitations to her salon or her balls (where she is said to have introduced the waltz to England, or at least of making this shockingly intimate dance respectable and fashionable). More than just a society hostess, Princess Lieven was considered almost as a second ambassador, and was known to be connected in some way to every diplomat and crowned head in Europe. In 1825 she acted as an informal interlocutor between Russia and Great Britain, conveying Alexander I’s thoughts about the growing conflict in the Mediterranean over Greek independence with the Foreign Secretary, George Canning, while they were holidaying at Brighton. She is also credited for getting her friend Palmerston appointed as Foreign Secretary in 1830; but this backfired when he quarrelled with Tsar Alexander in 1834 and the Prince and Princess Lieven were hastily recalled to Russia.

Back at the Russian court, Prince Christoph became governor and tutor to the young Tsarevich Alexander, while Princess Dorothea took up a post as Senior Lady-in-Waiting to Empress Alexandra Feodorovna. But she soon grew tired of Russian life, far from the diplomatic and cultural centres of Western Europe where she had flourished, so she left for Paris—never seeing her husband again before he died in 1839 while on Grand Tour in Rome with the Tsarevich. In Paris, Princess Lieven once again became a social and political force, hosting a salon in her residence in the First Arrondissement, and making friends with key statesmen like François Guizot, Minister for Foreign Affairs for much of the 1840s (and briefly Prime Minister of France). She attempted to act as a mediator once more for Russia, this time with France over the growing conflict in Crimea (1853), but was unable to prevent the outbreak of war. She died in Paris in 1857, leaving behind a vast treasure for historians of diplomacy in the form of letters and diaries, much of which has been published, covering nearly half a century, from the 1810s to the 1850s.

The third son of the original Princess Lieven, Johann Georg, also good a good start, as companion to Grand Duke Alexander in his first military campaigns in 1796. He served in all of Russia’s campaigns in the Napoleonic Wars and rose through the ranks to retire in 1815 as a lieutenant-general. He returned to Courland where he purchased an old castle at Cremon (Krimulda in Latvian). This castle had been built by the Livonian Order in the 14th century, and was mostly destroyed in the wars of the early seventeenth century. It would become the seat of the junior branch of the family, to which we’ll return at the end.

The third generation of Lieven princes was headed by Prince Otto Andreas (also known as Andrei Karlovich), born in 1798. Unlike princely titles in Western Europe, Russian princely titles did not really favour the eldest son in the same way, and with all children being titled prince or princess, so although the genealogist in me wants to call him the ‘3rd Prince Lieven’, this isn’t really accurate. Instead, elder brothers often spent their careers tending the family estates in the countryside, as head of the entail, while younger brothers could forge careers at court or in the military. In this case, Prince Andrei did rise, after an early suspicious involvement with the liberal Decembrist Uprising of 1825 (questioned, but not charged), to the rank of major-general in the army and commander of the Uhlan regiment of the Life Guards, but did retire early and married a cousin (another Princess Charlotte Lieven), to begin producing the next generation of Lievens on their estates in Livonia.

The most prominent Lieven prince of this generation, however, was indeed a younger brother, Alexander Friedrich, who started his military career auspiciously as aide-de-camp to the now quite close friend of the family, Tsar Nicolas I, in 1826. In 1844 he was appointed Governor of Taganrog, an important naval city on the Sea of Azov which the Romanov emperors often used as a summer residence. When he retired from active service in 1853, he was promoted to the rank of lieutenant-general and named a Senator of the Russian Empire.

Prince Alexander in turn had two prominent children: Prince Andrei Alexandrovich was Governor of the Moscow District, 1870, then a Councillor of State and Imperial Senator. In 1877 he was appointed Minister for Imperial State Properties, responsible for looking after the imperial estates all across Russia. In 1881 he retired to an estate at Spasskoye, near Moscow and devoted himself to the study of astronomy. Much later in life, a floundering Tsar Nicolas II once again turned to a member of this trusted family, and Prince Andrei was recalled to the State Council in 1910; he remained in government until his death in 1913. His descendants emigrated and founded a branch who emigrated to England and Canada.

Andrei’s sister Princess Helena (or Jelena) continued the family’s tradition of education, and made a name for herself as a pedagogue in Saint Petersburg where she was principal of the prestigious Smolny Institute for Noble Maidens from 1895 to her death in 1917 during the Revolution.

The fourth and fifth heads of the Lieven family did not leave much of a mark on history: Prince George and his brother Prince Michael both died within a month of each other in the summer of 1909. The senior position thus passed to a cousin, Prince Alexander Nikolaievich (b. 1876), who lived not at Mesothen (which by this point had been given to a junior branch), but at Senten (Zentene), still in Courland but much further north near the coast, west of Riga. Purchased by this line in 1818, a new palace was constructed here in 1850. They also owned a grand manorhouse in southern Courland called Fockenhof (Bukaišu). When riots broke out following the Revolution of 1905, Fockenhof was destroyed and Prince Alexander emigrated to Germany, where he died in 1919. Following the Latvian agrarian reforms of 1920, his cousin, Prince Nikolai, was allowed to live on at Senten, but as a tenant; nevertheless the government established a sanatorium there and he was gradually pushed out. Zentene Manor now houses a local school.

Prince Alexander’s son, also called Nikolai, was born in Dresden in 1906. He had no children with his first wife, and in 1949 he married a second time, to a French noblewoman (noble twice over: born into the old house of Bridieu, and adopted by a great-uncle of the Chateaubriand family), who inherited a château in the Rhône valley, in the heart of the Beaujoalais wine region. Their son Prince Alexander (b. 1953) is the current head of the princely house of Lieven (the ‘8th Prince’), and proprietor of the wineries at the Château de Bellevue where one of their best-sellers is named for his mother, Princesse Lieven. They have three sons whose names retain their Russian heritage: Nicolas, Pierre and Dmitri.

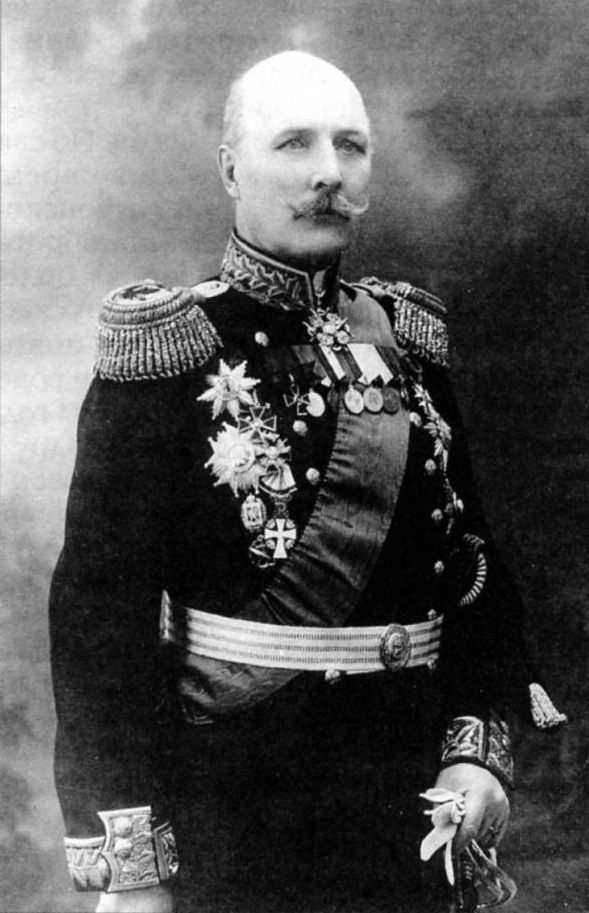

While there were by now many, many members of the Lieven family, one other stands out in this senior branch. Prince Alexander Karl (b. 1860) served in the Russian Imperial Navy and made his name as a brave captain whose vessel broke through enemy lines in the Russo-Japanese war of 1904-05. He was promoted to admiral in 1911 and served as Chief of the Navy’s General Staff in 1912, but died in February 1914 just before the outbreak of war.

Lastly, we come to the most junior branch of the princely Lievens, the descendants of Prince Johann Georg. In several ways, this became the most prominent branch of the family. Prince Johann’s son, Paul (b. 1821) became an important figure in politics in the Baltic provinces, and then one of the most senior members of the Imperial court in Saint Petersburg. In the 1850s he began to redevelop the castle at Cremon (Krimulda), in a region known as ‘Livonian Switzerland’. Perhaps adhering to this theme, he built two ‘Swiss chalets’ in its parkland that overlooked a romantic gorge of the Gauja river, which runs through this part of Livonia (northeast of Riga). When on a tour of the region, Tsar Alexander II heard of Cremon’s beauty and paid a special visit in 1862. Like the other properties in Latvia owned by this family, it was nationalised in 1920, and turned into a sanatorium. Today it is on the market for nearly 3 million euros.

The same year as the Tsar’s visit, Prince Paul was named Land Marshal of Vidzeme (the region in which Cremon was situated), and a few years later elected to the local Landrat, or parliament. With this platform he became a leader of the liberal party in the Baltics and worked to achieve freedom of religious expression in this part of the Russian Empire—recall that several members of this family were evangelicals. In fact, his wife, Princess Nathalie (born von der Pahlen, yet another of these Baltic German noble houses), was an avid adherent to the evangelical movement, and years later, as a widow, purchased a grand residence in Saint Petersburg (the former Demidov Palace), on fashionable Morskaya Street, where in the 1870s-90s she hosted famous Baptist preachers and convened great gatherings aimed at religious conversion. Sold in 1910 to the Italian Embassy, the building is now part of the Baltisky Bank.

Perhaps charmed by his visit to Cremon Castle in 1862, Tsar Alexander II named Prince Paul as one of his court chamberlains that same year, then in 1866 appointed him a Privy Councillor in 1870, and Master of Ceremonies of the Russian Court. This was a powerful position at court, as it controlled much of the Tsar’s activities and, crucially, access to the Tsar’s person.

But Paul was not finished building up his estates in Livonia: in 1874, he acquired the ancient ruins of Bauske Castle (Bauska in Latvian), not far from the other family seat of Mesothen Palace in the south of the country, the part of Courland called Semigallia. The site has a long history: the tribal Semigallians built a hill fort here, and later the Livonian Order constructed a stone castle (circa 1450), with a central tower and a prison and several buildings for a garrison. Its purpose was to guard the southern frontier against the grand dukes of Lithuania. When the Livonian Order secularised and became the duchy of Courland for the Kettler family in the mid-16th century, Bauske became one of their main residences, and was used as a meeting place for the local estates. The duke of Courland modernised it in the 1590s, but just over a century later it was blown up by invading Russian forces in 1706. Prince Paul Lieven purchased the ruins and restored the ducal palace (leaving the older medieval fortifications as a romantic ruin). Today it is open for tourism.

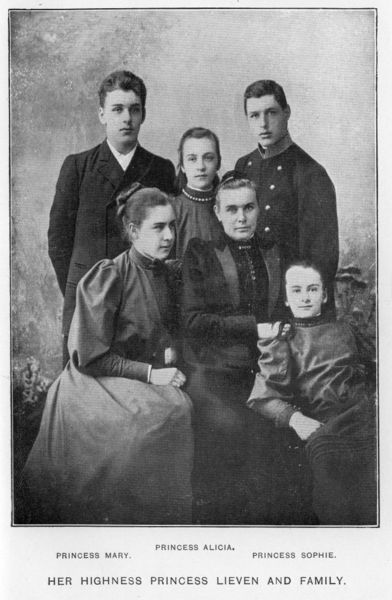

Prince Paul Lieven, Master of Ceremonies, liberal reformer, builder of palaces and gardens, died aged only 60 in 1881, leaving behind his widow Princess Nathalie, and several very young children. The eldest, Anatol, was only 9. He followed in his parents’ footsteps in politics and religion, and in 1900 became a member of the Courland Peasant Affairs Council, and in 1909 chairman of the Council of the Russian Evangelical Union. In 1903, he built a brand new Lieven residence, Pelzen Palace (Pelči) in the far west of Courland, in art nouveau style. Today it is a school.

Prince Anatol served as a cavalry captain during World War I, then became a commander of a Russo-German battlegroup (the Liventsy) in the Latvian War of Independence, 1918-20. Though allied with the Russian ‘White’ armies fighting against the ‘Red’ armies of the Soviets, he also faced pressure to assist in a pro-Imperial Germany takeover of the new Latvian government, which he wouldn’t do. He also forbid his soldiers from fighting against an Estonian army that was seeking to expand that new nation’s territory from the north.

When the war ended and the Latvian Republic secured its independence, Prince Anatol’s estates were nationalised (as we’ve seen already), including the main estate, Mesothen, now called Mežotne in Latvian. The age of the Baltic German nobility had come to an end, but Anatol Lieven did not emigrate like many others. He obtained permission to keep part of the estate and converted it into a brick factory, which he ran successfully for many years until he died in 1937.

Anatol’s younger brother, another Prince Paul, was also a liberal reformer, and long before revolution or nationalisation, had already converted his estate (purchased in 1893), Smilten (Smiltene), in Vidzeme (not far from Cremon/Krimulda), into something productive for the general populace. Trained as an engineer, he developed roads around the estate and built its own short railway line, as well as a power station, a hospital and a sawmill. He divided up the estate into smaller rentable plots for local people. Yet unlike his brother, he did not stay in Latvia to participate in the agricultural reforms of the 1920s; he migrated to Germany in 1919, then to England, where he died in 1963.

Both Anatol and Paul left descendants, the former in Canada and the latter in England. Paul’s son Alexander Lieven, born in Rostock in northern Germany in 1919, grew up in England, and served as a Captain in the British Army in World War II, then worked in the Foreign Affairs office as a Russian specialist. In the 1960s-70s, he was Head of the Russian and East European Service for the BBC.

Finally, four of the five children of Alexander Lieven (who died in 1988) have all maintained their family’s notoriety, all in very different fields. The eldest, Elena, is a developmental psychologist at Manchester University and the Max Planck Institute in Leipzig. The youngest, Natalie, is a magistrate who in 2019 was appointed a Justice of the High Court of England and Wales, and Dame Commander of the British Empire. Brother Anatol is a prominent journalist and policy analyst specialist on counter-terrorism. While last but not least, is my colleague in the study of the history of monarchy and aristocracy, Professor Dominic Lieven, of Cambridge University, whose many books focus on, what else, Imperial Russia.

(images from Wikimedia Commons)