Spain’s ‘Golden Century’ was dominated politically by powerful men known as validos, a combination of prime minister and personal servant, the closest confidant and advisor to the king. The reigns of Philip III and Philip IV were monopolised by three men, Lerma, Olivares and the latter’s nephew Haro. The first was created Duke of Lerma (1599), and his son Duke of Uceda (1610). The second was created Duke of Sanlúcar la Mayor (1625), but used the curious hybrid title of ‘Count -Duke’ of Olivares; his son-in-law (and at one point anticipated successor) was given the dukedom of Medina de las Torres (1626). The third, while ultimately inheriting the Olivares title, was given his own dukedom of Montoro (1660).

This post is thus about three families—the House of Sandoval de Lerma, the House of Guzmán de Olivares, and the House of López de Haro—and at least five ducal titles between them. All three validos were part of wider dynastic clans, or casas; in particular, the House of Guzmán had many branches, and one of the oldest and grandest dukedoms in Spain, Medina Sidonia (1445). But since that dukedom has very much its own story, and indeed continued into the modern era in a different family line (as Spanish dukedoms passed freely through female lines), I will write about it separately.

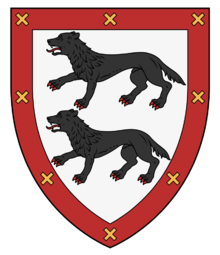

Like many Iberian families, the histories of these three families is long and sometimes emerges from shadows into national and international prominence, then fades more into the background, only to emerge once again to prominence in a different branch. López de Haro is a good example of this. While they were not dukes or princes, the early members of this family were amongst the most powerful nobles in Spain in the Middle Ages, with generations holding the title Lord of Vizcaya—the province of Biscay, or the Basque Country. They originated in the town of Haro, in the province of La Rioja, one of the contested frontier areas between Vizcaya and the early medieval kingdoms of Navarre and Castile. Iñigo López Ezquerra was appointed governor of Vizcaya in about 1040, and converted his rule into a hereditary title by the 1070s. His son and grandson served the kings of Castile and Leon in their wars of re-conquest against the Moors (Toledo, 1085, Zaragoza, 1118). Diego II, the 5th Lord, rose to the positions of Alferez del rey and Mayordomo mayor in 1183, the top positions at court, and was one of the greatest magnates of the reign of King Alfonso VIII of Castile. Like many of his kinsmen he fought at the battle of Las Navas de Tolosa in 1212, which effectively destroyed the power of the Almohads in Iberia. In 1187 he married his sister Urraca to King Ferdinand II of Leon, solidifying their family’s access to royal favour and power through blood. Several other kinsmen would marry into the various royal houses in the next generations, including Mencia who married in 1240 Sancho II, King of Portugal. They adopted a the symbol of the wolf on their coat of arms (from lupus, or lobo, wolf).

The height of the López de Haro power was probably reached with Lope Diaz III, 8th Lord of Vizcaya, who was still Alferez and Mayordomo of the king, and backed Sancho IV in his usurpation of the Castilian throne from his nephew—Lope and Sancho were married to sisters (grand-daughters of the king of Leon), making their bond even greater. But his power made other nobles jealous, and they concocted an argument between the two men resulting in Lope pulling a knife on the King and his subsequent execution in 1288. By the early 14th century, the senior line died out, and the lordship of Vizcaya passed into the House of Lara, one of the other great magnate families of the Kingdom of Castile in this period.

Back in the 1280s, the son of the 8th Lord of Vizcaya had supported the rival of King Sancho, the dispossessed Infante Alfonso, as did one of the early members of the House of Guzmán. This family arose a little bit later, and bit more to the south, in the province of Burgos in Castile. There is a village here with the name Guzmán, which some have suggested was named for early Germanic (Visigothic) settlers (‘good man’) or for a Visigothic king or chieftain named ‘Gudemar’. Whatever the case, documents show Rodrigo Muñoz de Guzmán as a patron of several monasteries in the region in the 1180s, and tenant-in-chief of the lordship of Roa in the Duero valley. There is a ‘Guzmán Palace’ in the village, built in the 17th century by a member of a minor branch, which today serves as a municipal centre.

There is also a ‘house saint’ in this very early period, though any firm connections are conjectural—he may simply have come from the same town. This is Santo Domingo de Guzmán, better known in English as Saint Dominic, the founder of the Dominican Order in the early years of the 13th century.

The great rise to prominence of the Guzmáns came just as the early López de Haro lords were fading away. Alfonso Pérez de Guzmán ‘el Bueno’ was one of the noteworthy conquerors of Andalusia in the 1290s, famously capturing the castle of Tarifa—at the southernmost tip of continental Europe. He was rewarded with the important lordship of Sanlúcar de Barameda, guarding the mouth of the river Guadalquivir, near Cadiz, and the lordship of Medina Sidonia, a bit inland, and one of the most ancient towns in the region—possibly founded by Phoenician colonists (and named for their hometown of Sidon; Medina is Arabic for ‘city’). He was given the fortress of Tarifa to defend, which he did, famously, in 1294, in throwing his knife down to besiegers who had captured his son—indicating he would rather sacrifice his son than disappoint his king.

Less glamorously, El Bueno was also given the rights to fish tuna in this coastline, one of the most lucrative in the area, and upon which his family built much of their great fortune—the ‘tuna fortress’, Zahara de los Atunes, still stands today. By the end of his life, he had helped Ferdinand IV take the Rock of Gibraltar (1309), and had founded one of the grandest Andalusian aristocratic lineages still extant today. One of his descendants, Juan Alonso de Guzmán el Bueno (they had added this to the surname), was created first Duke of Medina Sidonia (1445), and the family continued to dominate the provinces of Cadiz and Seville for generations. Their residence is still the Palace of Medina Sidonia in Sanlúcar, near Cadiz. As said at the start, I will cover their story separately.

But to get back to the medieval Guzmáns, we need to know exactly who were the parents of ‘El Bueno’. This seems a bit murky. There has been recent speculation that he was a Moor himself who converted, and indeed there is evidence from his life that he played a strong role as a negotiator between Christian and Muslim warring parties, not merely a conqueror. The more traditional answer is that he was the illegitimate son of Pedro Guillén de Guzmán, one of the key military governors of Castile in the reigns of Ferdinand III and Alfonso X. Pedro Guillén’s sister was Mayor, the mistress of Alfonso X and mother of Beatriz, wife of King Alfonso III of Portugal—so, like the López de Haro lords above, royal blood (legitimate or illegitimate) ran through Guzmán veins. Their cousin Pedro Ruiz (or Nuñez), head of the senior branch, was Adelantado mayor (a military commander) of Castile and married the heiress of the lordship of Roa, in Burgos (a town we have already encountered, above), upon which they built the foundations of their dynasty in the north (while El Bueno’s descendants established themselves in the south). In 1312 they acquired the lordship of Toral, near the city of Leon, and this would become this branch’s primary title, raised to a marquisate in 1612. The 2nd Marqués del Toral will turn up in our story of Olivares, below.

The third family covered in this blog post, Sandoval (or Gómez de Sandoval), rose to great prominence last, completely dominated Spain for a brief time, then vanished. They too traced their roots to the early medieval re-settling of northern Castile in the 12th century. Like the Guzmans their name came from a small town in Burgos province, possibly from Zandabal, ‘next to the thicket/grove’. For generations they remained minor local lords, then in the late 14th century Fernán de Sandoval married Ines de Rojas, heiress of lands further to the north, and the riches of an uncle, the Archbishop of Toledo. Their son bore both surnames, Sandoval and Rojas, and was raised to the higher level of nobility, as count of Castrojeriz (near Sandoval, 1426), and as count of Denia, an important town in the Kingdom of Valencia, near Alicante (1431)—a detail that will become important in the career of the valido Lerma, below.

The next generations of Sandovals married into the highest Castilian nobility. Denia was raised to a marquisate in 1484, and another property in Burgos province, Lerma, was raised to a county. The 2nd Marqués of Denia married a cousin of King Ferdinand of Aragon, and in the following generations, the Sandovals became intimates of the royal family at court. Francisco de Sandoval Rojas (1553-1625) was the son of the 4th Marqués, a Gentleman of the Chamber of Philip II, and of Isabel de Borja, a daughter of St. Francisco, duke of Gandia. He was an early friend of the heir to the throne, Prince Felipe, and served as his Caballerizo mayor (the officer in charge of his stables); then when the Prince succeeded as Philip III in 1598, Sandoval swiftly took control of the government as the new king’s chief confidant and advisor. In 1598 he was named Sumiller de Corps, the most intimate office within the royal household in Spain, in charge of the King’s private rooms and his person (dressing, cleaning, etc). He still held the post Caballerizo mayor, which meant that he was also the most intimate officer outside the royal residence, when the king went around on horseback. These two offices joined together, interior and exterior, would define the post of Valido for the century to come.

In 1599, Sandoval was created duke of Lerma, his son was created Marqués of Cea (a rich lordship in northern Leon), and his cousin Bernardo was promoted to the archbishopric of Toledo (the most senior position in the Spanish church) and made a cardinal. Cardinal de Sandoval was later Grand Inquisitor of Spain—so between them, the Duke and the Cardinal could control both church and state. Lerma’s wife Catalina became the Camarera mayor (head of the household) of the new queen, Margarita of Austria. Lerma’s rule was bold: he made peace with France finally in 1598, but failed to stop the war with the Dutch, leading to state bankruptcy in 1607. In a diversionary tactic, he ordered the expulsion of Moriscos, the descendants of converted Muslims, primarily from the Kingdom of Valencia, in 1609, and he made a great show of overseeing this personally in his marquisate of Denia. This brought him great popularity with the clergy and the populous of Spain, but wrecked the economy of Valencia for several generations.

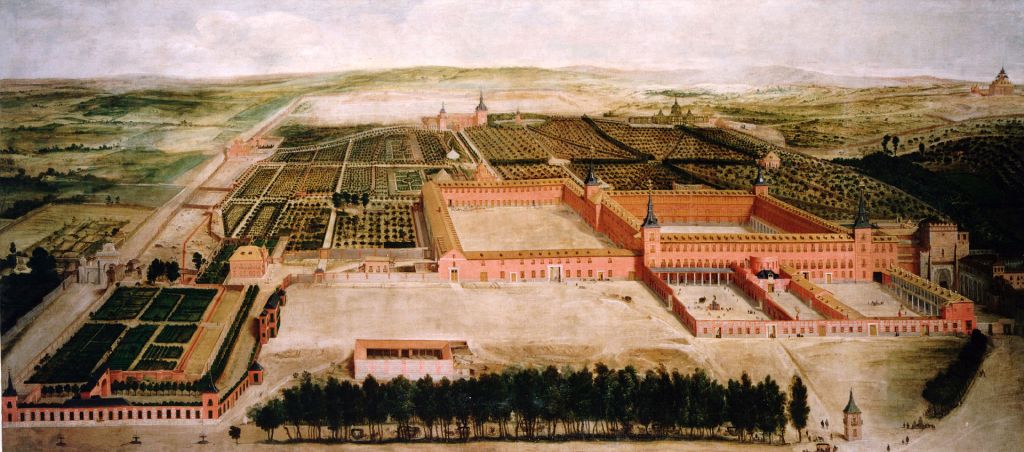

As a bit of a control freak, Lerma convinced the King to move the Spanish court away from Madrid to a new palace, La Ribera, in Valladolid, in 1601, and he built himself a grand palace not far away at Lerma, an old medieval walled town, from 1606. The ducal palace of Lerma was built with four corner towers, at a time when no residence could have more than two towers except those belonging to kings. Lerma was now like a second king.

The great favourite helped his son, Cristóbal, acquire the town and county of Uceda, in Guadalajara province (just north of Madrid), in 1609, and it was raised to a separate dukedom in 1610. Cristóbal also built for himself at this time a huge palace right next to the royal palace. In later years it was judged to be too ostentatious to be held by a non-royal person and was confiscated by the Crown. In the later 17th century it became the residence of the Queen Mother, Mariana of Austria, and today the it houses the Council of State.

The 1st Duke of Uceda continued to aspire for more power and more influence, and in 1618, conspired to overthrow his own father. He was successful in replacing him as Sumiller de Corps and Caballerizo mayor, but was soon outmaneuvered and replaced by the rising favourite of the next heir to the throne, the Count of Olivares. Uceda was exiled from court, his properties confiscated; he was later jailed and died in prison in 1624. His father fared somewhat better—seeing the writing on the wall, he had asked the Pope to make him a cardinal (his wife had died long before) in 1618, a few months before the coup, so that he would have clerical immunity. The ‘Cardinal-Duke’ therefore retired peaceably to Lerma, but in the new reign, that of Philip IV, he was forced to return huge sums to the state in 1624, and he died, broken, in 1625.

A grandson, Francisco, was for a short time both duke of Lerma and Uceda, and when he died in 1635, his daughters were each given one of these titles. Uceda passed into the House of Téllez-Girón, which also preserved the name Gómez de Sandoval (and merged with the dukedom of Osuna). Lerma eventually passed into the hands of the great Mendoza family (joining with their dukedom of Infantado), then into other grand aristocratic houses and mostly lost amongst the dozens of dukedoms accumulated by the great grandee families of the 19th century. In the 20th century, the ducal palace at Lerma was used as a concentration camp by the fascists in Spain, but today is restored to its former glamour and houses a luxury hotel.

No such spectacular buildings remain to memorialise the second of the great Validos, the ‘Count-Duke’ of Olivares, who had replaced the Duke of Uceda as royal favourite in 1621. He was the grandson of the 1st Count of Olivares, Pedro Pérez de Guzmán. The youngest son of the 3rd Duke of Medina Sidonia, Pedro was given by his father the lordship of Estercolinas, west of the city of Seville, in about 1507. The lordship was renamed Olivares perhaps to reflect the abundant olive groves, another source of the family’s great wealth in the region. The building constructed to house this new branch of the Guzmán family does survive (the Palacio de Olivares) and today serves as the town’s municipal offices.

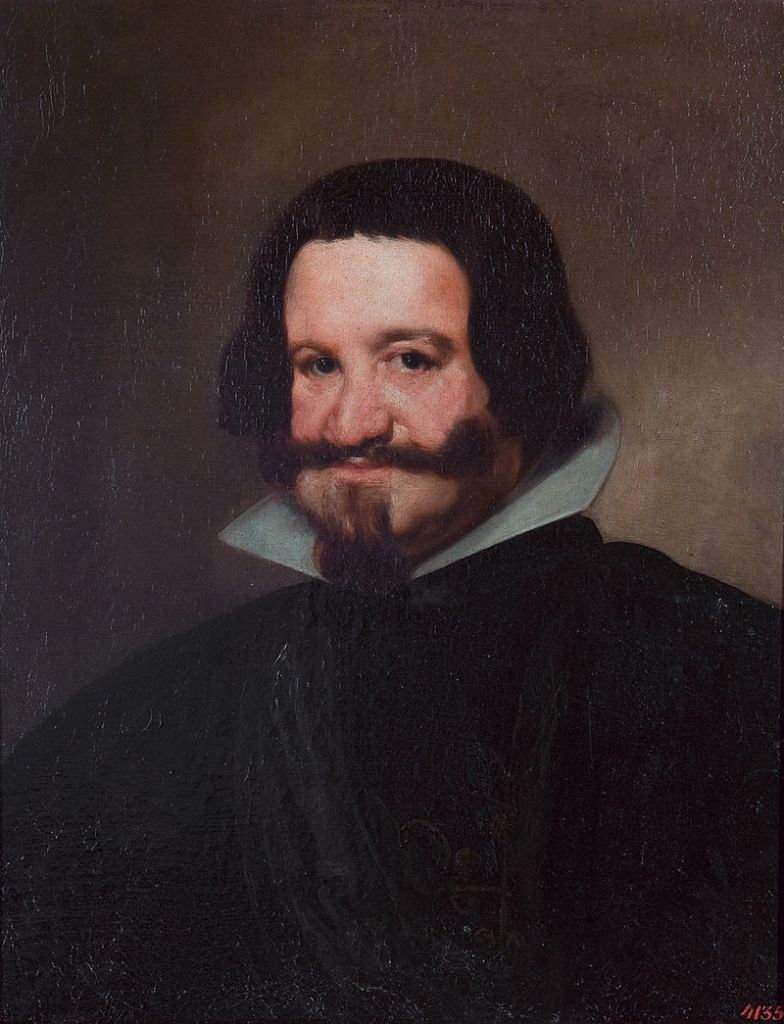

Pedro served Charles V abroad in his wars in Italy, Germany and North Africa, and was rewarded with the title Count of Olivares in 1539. He used his affinity with the King to profit from new laws permitting the ancient military orders to sell off their lands in Andalusia. His son, Enrique, now a very wealthy man, continued to serve the Spanish king (now Philip II) in his wars, but also at court, holding a wide variety of prominent positions: Treasurer of Castile, Governor of the royal palace of Seville and Ambassador to France and to Rome. Towards the end of his life he was appointed to the most prestigious offices: viceroy of Sicily (1592-95) then viceroy of Naples (1595-99). His son, Gaspar (b. 1587), the 3rd Count of Olivares, was thus set up very well.

Gaspar had been born in Rome, then at a young age was placed in the household of the heir to the throne. Once the prince became King Philip IV in 1621, Olivares soon assumed the position of Minister-Favourite, the King’s most trusted advisor, so close to his sovereign that some considered him like the King’s alter-ego. In fact, one of the most prominent characteristics of the rule of Olivares in the next two decades was his almost overwhelming dedication to hard work, all in the service of allowing the monarch to be more detached from government, more mystical and removed from the common people, and bringing order back to the administration of the Spanish monarchy. He even built a new palace for the King, the ‘Buen Retiro’, a place where he could ‘retire’ from the bustling city and enjoy himself amongst its gardens and waterways. Constructed in the 1630s, the new palace’s interiors were decorated with paintings by Velázquez and frescoes by Luca Giordano. Olivares is seen by some to be the architect of the last great burst of Spain’s golden age.

Others saw him quite differently, as someone who relentlessly pursued centralisation, to the detriment of the Church and the old nobility. He re-started the Dutch War and provoked war with France, reigniting Spain’s financial woes and skyrocketing inflation. By 1640, the strains were so great that independence movements broke out in Portugal and Catalonia, followed by a revolt in Andalusia of the old nobles—led by his own cousin, Gaspar Alfonso Pérez de Guzmán y Sandoval, 9th Duke of Medina Sidonia, whose mother was a daughter of the Duke of Lerma, and whose sister was married to the newly proclaimed king of Portugal. Although he managed to hold on to Catalonia and to supress the revolt in Andalusia, decades of overwork took their toll and Olivares started losing control of his mind. He was forced out of government in January 1643, retired to his sister’s palace in the far west of Spain, and died there, in 1645.

Olivares’ succession was confusing. He had been rewarded with a dukedom in 1625, on the town of Sanlúcar la Mayor, in the province of Seville. He wanted to remain known as ‘Olivares’, so rather than change title, he morphed the two into the title ‘Count-Duke of Olivares’ (an unusual occurrence I have not seen anywhere else—and I don’t understand why the King didn’t simply create a duchy of Olivares).

But one dukedom was not enough. Following the precedent set by Lerma, to secure his family’s pre-eminence, he had a second dukedom created, Medina de las Torres, for his daughter and her husband, another Guzmán cousin, Ramiro Nuñez de Guzmán, 2nd Marqués de Torral, selected by the Valido from the senior but more impoverished branch of the family (noted above). Medina de las Torres was a town (‘medina’ in Arabic) with an old Moorish fortress (‘las torres’, the towers) in Extremadura in the far west of Spain, near the border with Portugal.

But the Duchess, Olivares’ only legitimate child, died only a year later. Her widower remarried, a woman not approved by the Valido, and fell from his former father-in-law’s favour. His marriage saved him, however, as she was a Carafa, one of the most powerful Neapolitan princely houses, and through her influence (and his own personal favour with Philip IV), he was named Viceroy of Naples, in 1636. Through his wife he also held the lofty Italian titles, Prince of Stigliano, Duke of Mondragone, and Duke of Traetto. These titles, and Medina de las Torres, passed to their son, but he had no children, so the Italian titles were inherited elsewhere and the duchy of Medina de las Torres passed to a half-sister (from his father’s third marriage), and then into the House of Osorio.

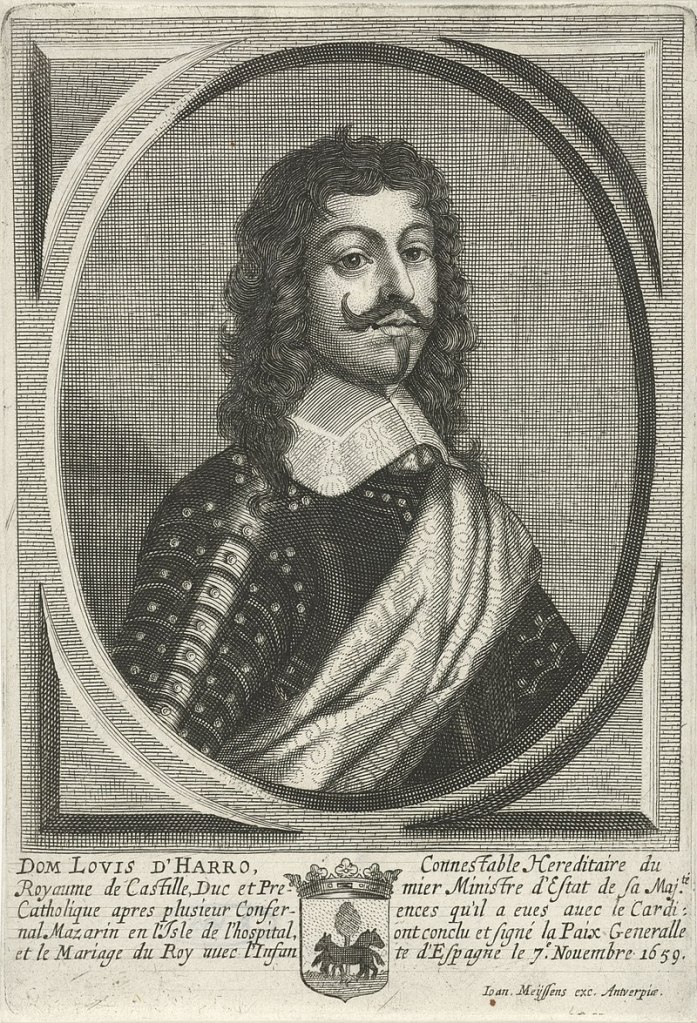

(some fantastic mustaches in this post!)

Annoyed with his supposedly docile and controllable son-in-law’s independent re-marriage, Olivares decided to legitimise his bastard son Juliano, renaming him Enrique Felipez, in 1642. He was named heir to the duchy of Sanlúcar, while the county of Olivares passed to his sister’s son, Luis de Haro (see below). Enrique died a year later, followed by his own son, the 3rd Duque de Sanlúcar la Mayor, only two years later. After a legal battle, a cousin (the son of Olivares’ aunt) was awarded the dukedom, and it remained in his family (Dávila) for several generations (though they preferred to be known by the title, Marqués de Leganes), before passing to the ducal House of Osorio. These two dukedoms, Medina de las Torres and Sanlúcar la Mayor were thus re-joined together in the same family.

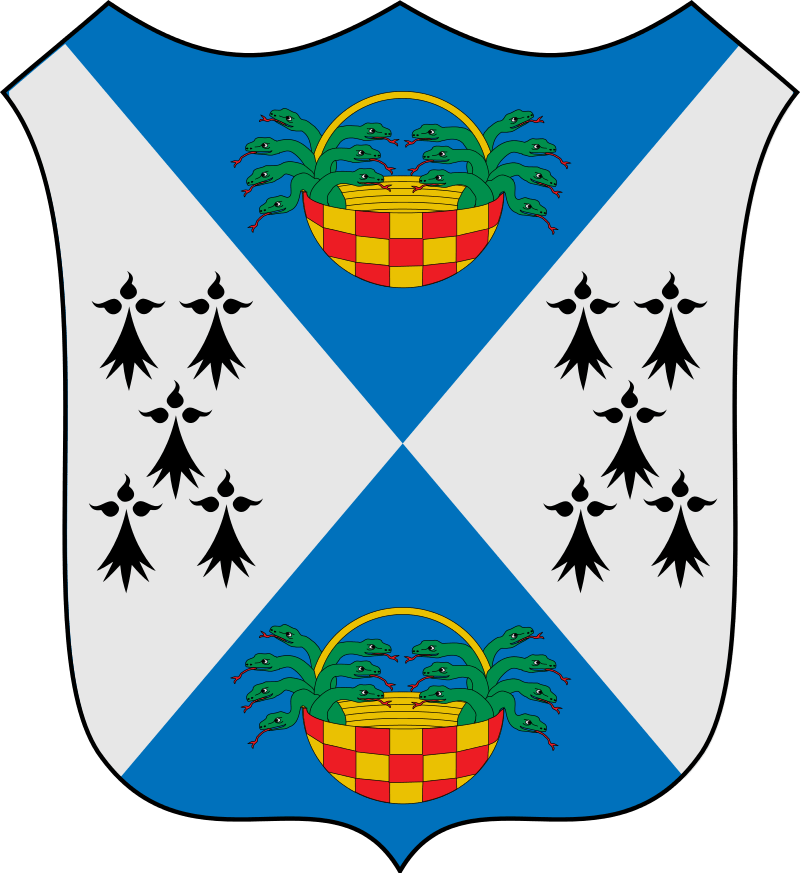

The nephew who became the 4th Count of Olivares, Luis Méndez de Haro, in 1645, succeeded his own father soon after (1648) as the 6th Marqués del Carpio, and in that same year was given the court office of Caballerizo mayor, thus confirming his place as the new Valido of Philip IV. Like his predecessors, Haro relied on his close personal favour with the King for his power, though he exercised it in a different manner, much more subtly, much more interested in unifying the court and making peace with Spain’s neighbours. He didn’t even use a title, usually called simply ‘don Luis de Haro’. The marquisate of Carpio was a major estate in the south of Spain, in the province of Cordoba. A junior branch of the ancient House of López de Haro had acquired it through marriage in the late 15th century to the heiress of the Méndez de Sotomayor family—subsequent generations would use the surnames of either López or Méndez de Haro.

The lordship of Carpio was raised to a marquisate in 1559, and the family built up significant wealth in the provinces of Cordoba and neighbouring Seville. The 5th Marqués made his father’s office of Caballerizo de las Reales de Cordoba (master of the royal stables) into a hereditary post in 1625, and placed his son, Luis, in the orbit of the Minister-Favourite, his uncle Olivares.

Having succeeded as Minister-Favourite himself from 1643, Haro was at first successful in putting down the revolts in Catalonia and Naples, and ending the war with the Dutch. He restored order domestically, and finally brought France to the negotiating table resulting in the Peace of the Pyrenees of 1659. He was rewarded finally with a dukedom of his own: Montoro, a town in a bend of the Guadalquivir river, northeast of Cordoba. But he did not live long to enjoy this success, dying a year later in 1661.

The 1660s and ‘70s were thus decades of a balance of power between the remnants of some of these families. Haro’s eldest son, Gaspar (known as the Marqués del Carpio, not Montoro or Olivares) was exiled from court in 1662, but later became a diplomat and foreign advisor to Queen Mariana, regent for her son King Carlos II. In his absence, foreign affairs was often controlled the Duke of Medina de las Torres, Olivares’ former son-in-law, though counter-balanced by Haro’s uncle, the Count of Castrillo. Haro’s second son, the Count of Monterrey, became a prominent governor in the 1670s, in the Low Countries and in Catalonia. Back in Madrid, his older brother, Carpio hoped to become yet another valido, but his aspirations were dashed by the palace coup led by Philip IV’s illegitimate son, Don Juan, in 1677. He went to Rome as ambassador, where he became a great patron and collector of art, then moved on to serve as Viceroy of Naples, 1682, where he died in 1687.

As the Spanish Golden Century came to a close, the last valido’s grand-daughter, Catalina de Haro, married into the great Alvarez de Toledo family, taking with her the duchy of Montoro, the county of Olivares (which the family still refer to as a ‘county-duchy’—though only recognised as such by a royal decree of 1882), the marquisate of Carpio, and many other properties. The Duke of Alba today continues to list these amongst his great number of aristocratic titles.

(images from Wikimedia Commons)

Simplified family charts for Sandoval, Lerma and Haro