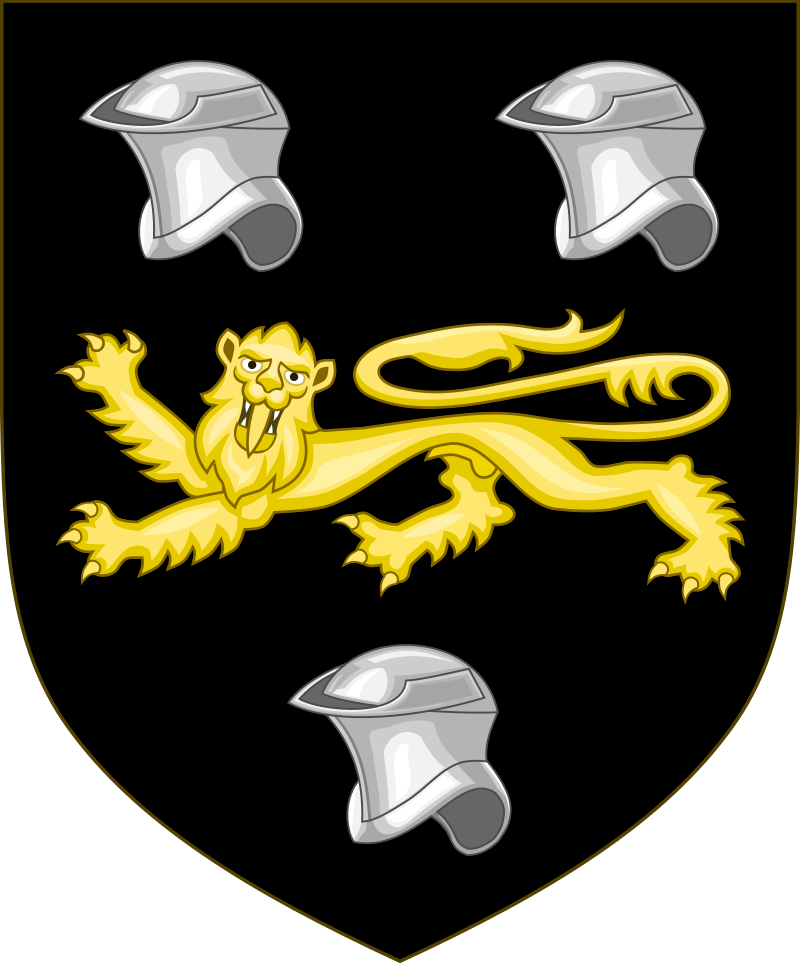

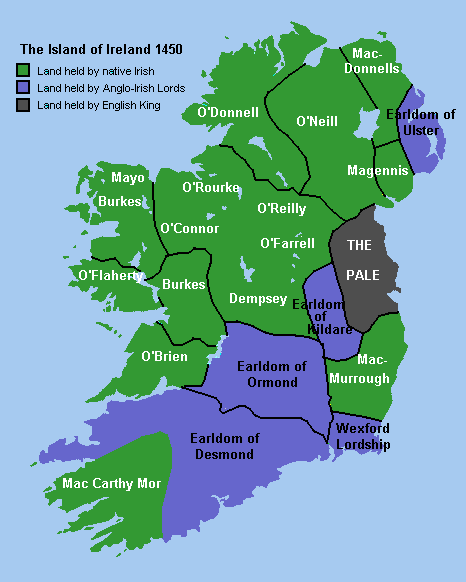

Ireland did not have dukes and princes created by emperors or kings in the manner of other European kingdoms in the medieval and early modern ages. There were a few dukedoms (Ormond, Leinster, Abercorn), but these were all created for Anglo-Irish families who had emigrated to the Emerald Isle at some point after its conquest by the English monarchy in the twelfth century. Ireland did have its own native nobility, however, with very ancient pedigrees, who divided the island along clan lines and small kingdoms, and occasionally came together to select a high king. This blogsite has looked briefly at the histories of the O’Neill kings in Ulster and the Kavanagh kings in Leinster — now it is time to look at the Irish kings who retained a degree of their independence longer than the others: the MacCarthys, kings of Munster. But this site is about dukes and princes, not kings, so I will focus on the story that unfolds mostly after the English invasion, when the MacCarthys took slightly lower titles, as princes of Desmond, Carbery or Muskerry, and when briefly there was a dukedom created for them—by the exiled Jacobite kings in France—that of Clancarty.

This family is vast and has many branches. Their names are spelled in many different ways, whether Anglicised or in various spellings of Irish Gaelic. Its history is at times convoluted, confusing or even contradictory, since it was passed down orally by Irish bards or written down erroneously by English monks with an agenda. I’ll do my best to sift through all this. But first, in a blog about dukes and princes, we need to consider terminology. Irish kings are usually called rí. A ruiri (‘over-king’) was superior to a rí túath (‘king of a people’), or what we might call a regional prince. The provincial kings (Ulster, Leinster etc) were called ‘king of the over-kings’, rí ruirech, and the Ard Rí was the High King over all these. After the invasion of Ireland there were no more high kings, and the English authorities preferred to call these lesser kings simply ‘earls’ (or ‘prince’ if they were favoured), then formalised this term through a system of ‘surrender and re-grant’, by which the local prince surrendered his lands and sovereignty to the English Crown in return for a legally recognised title in the Irish peerage. We will see that the last of the main line of the MacCarthy princes became earls of Clancare or Clancarty, and other clan chiefs became viscounts or barons. As noted, one of these was even given a dukedom, but only in the Jacobite peerage, and never recognised formally by any British government—though they were by Britain’s enemies in France or Spain.

The other detail that complicates the telling of the MacCarthy story is the system of inheritance used by the Irish until the end of the sixteenth century: tanistry. Rather than passing leadership of a clan or a kingdom always from father to eldest son as in the primogeniture-based systems prevalent in England, France or Spain, an Irish ruler had a tanist (tánaiste) as his heir apparent, usually selected by the elites of the clan. Quite often this was a king’s younger brother, with the assumption that the king’s son would then in turn be named tanist of his uncle, and then the uncle’s son after that. This system had the advantage of avoiding royal minorities, so an adult male was always in command, to best defend the clan or the kingdom, but also to ensure that power was not overly concentrated in one single patriline, but shared out amongst a few closely related lines. That said, some historians comment on how unusual it was for the MacCarthys to have such continuity of father to son kings, from the fourteenth to the sixteenth century, avoiding civil war that destroyed many other Irish ruling dynasties. In a manner similar to French kings, they created ‘apanages’ for younger sons, in this case the three main junior branches of the family: Duhallow, Carberry and Muskerry. The head over all of these was referred to as the ‘Great MacCarthy’ or MacCarthy Mór.

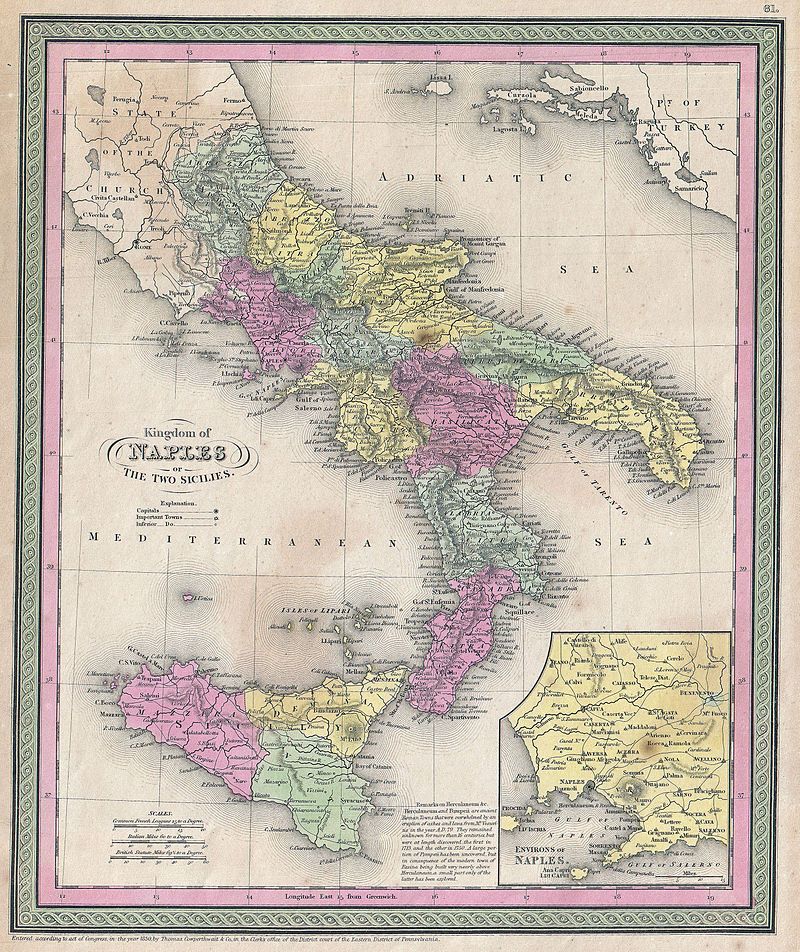

The MacCarthys are often reported to be the oldest native Irish lineage supported by records, not just legends. But legends there are, and these (like most Irish kings) trace back to the ‘Milesians’, the sons of Mil who sailed from Iberia to Ireland and defeated its local gods/kings and populated the island. One the descendants of these Milesians was Ailill Ollamh (or any of a number of spellings), king of the southern half of Ireland sometime in the 3rd century. He married Sadb, a daughter of the famous ‘Conn of the Hundred Battles’, High King of Ireland, and had three sons. The eldest, Éogan Mór (‘Owen the Great’) founded the royal house of the Eóganachta (sometimes called ‘Eugenians’ in older English-language histories) who became the MacCarthys, while the second, Cormac Cas was progenitor of the Dalcasians or O’Briens. These two royal houses contended for power in Munster for the next five hundred years. Munster itself, Mumhan in Irish, is thought to have evolved from mó (great) ána (prosperity), and over time was divided into Thomond (North Munster) for the O’Briens and Desmond (South Munster) for the MacCarthys. But there’s also Ormond (East Munster) which developed as a separate kingdom, but early on was transformed into an Anglo-Norman earldom for the Butler family (who will have a separate blog post, as dukes of Ormonde).

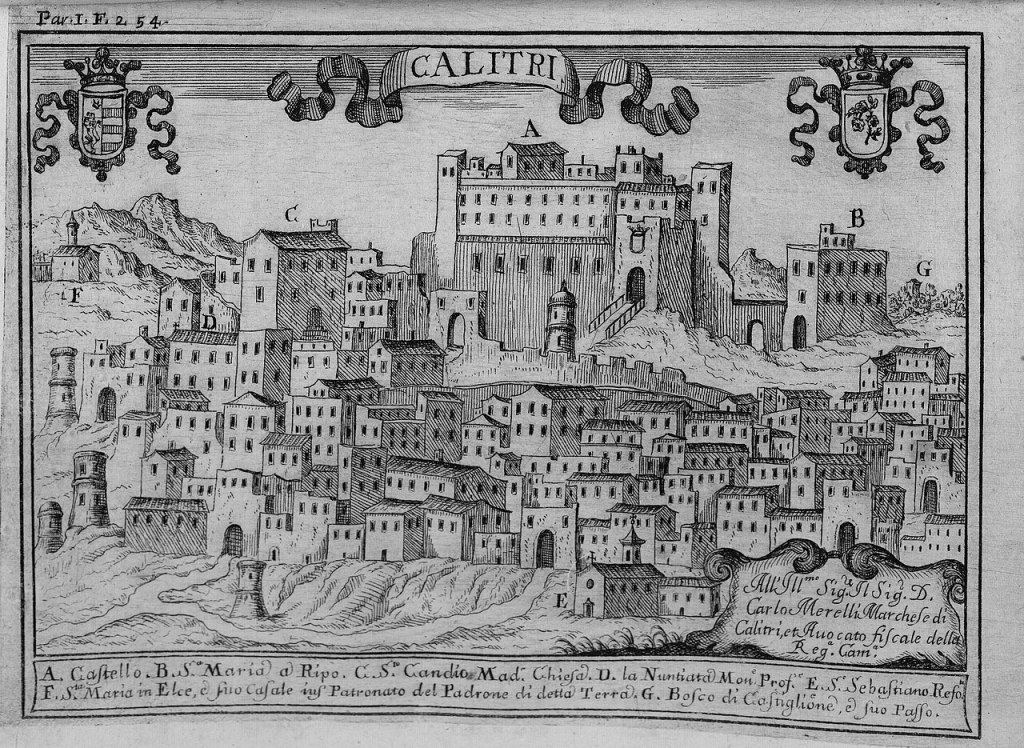

In the fifth century, one of the Eóganachta, Corc, became king of all of Munster and founded a new royal capital on top a great rock at Cashel. His grandson Aongus converted to Christianity and built a church on the same site—thus creating the fascinating blended royal-clerical complex of buildings that persist as ruins at Cashel today—and indeed many of their successors were titled both ‘king’ and ‘archbishop’. The last king of an uninterrupted line was killed in 960 and the O’Briens dominated the region for the next century. A later king, Carthaigh, re-asserted the independence of his clan and fought off Viking invaders on the south coast and O’Brien warriors to the north, before he was killed by the latter in about 1045. His son Muircadach used the usual patronymic ‘son of Carthaigh’, or mac Carthaigh, and this became the clan name. His sons, Tadhg, Cormac and Donogh, re-established an independent kingdom of South Munster (Desmond) by the Treaty of Glenmire, 1118, and ruled the kingdom in turn according to tanistry—though not without conflict: Cormac deposed Tadhg (and banished his sons), and was in turn deposed by Donagh. These early kings of South Munster were sometimes called ‘king of Cork’ or sometimes ‘king of Cashel’.

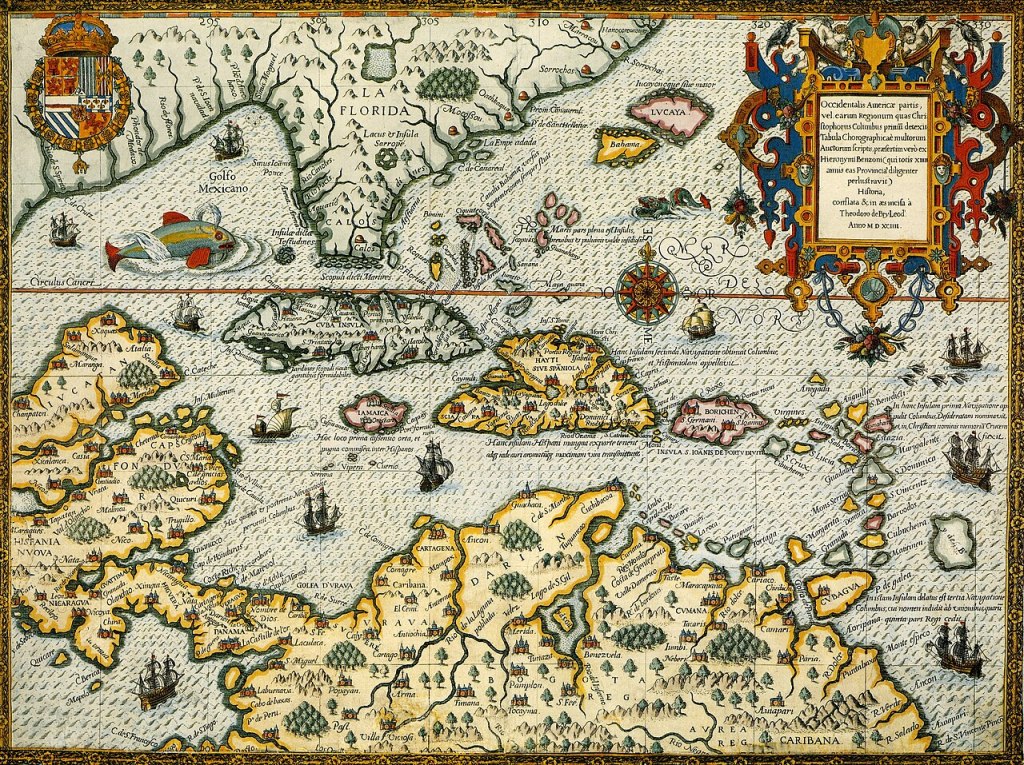

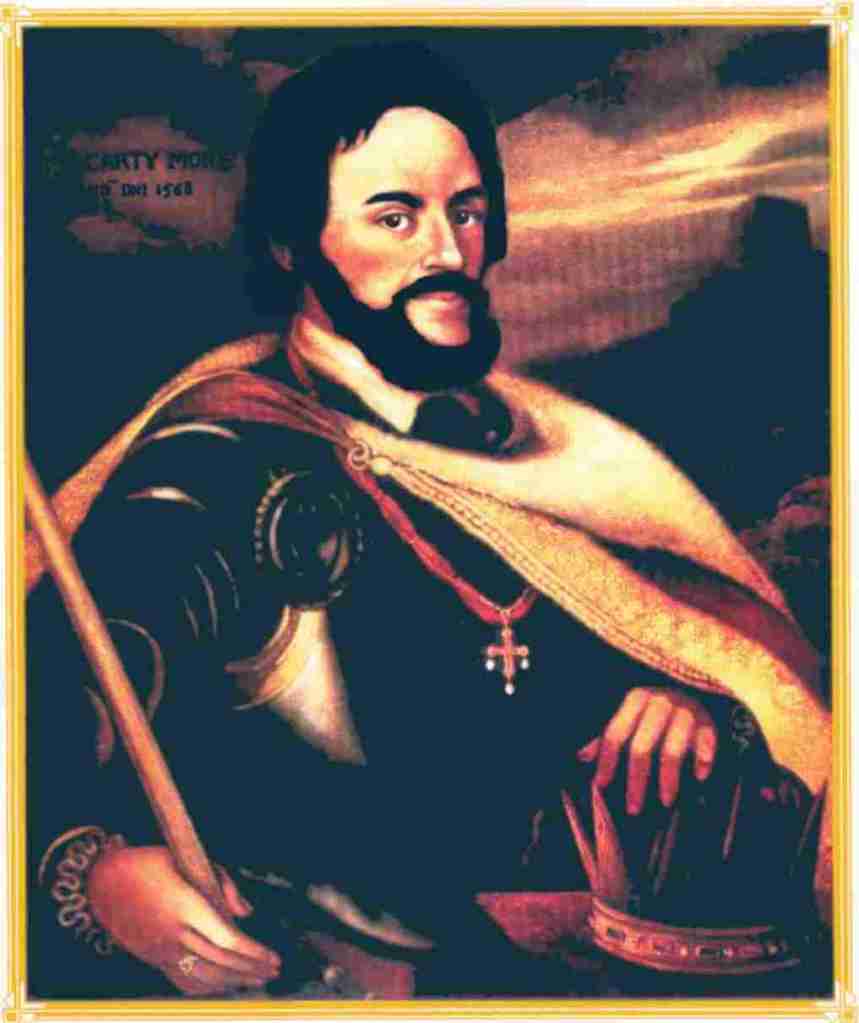

The son of Cormac MacCarthy, Diarmait, was one of the first Irish lords to submit to King Henry II of England, at Waterford in 1171; but instead of recognising his kingship, the English king granted Desmond to the FitzGerald family (also known as the Geraldines), who from then on competed with the native Irish in this region for centuries. King Diarmait thus began to push to re-settle his people further into the south and west, in Kerry. Diarmait’s son, Cormac, briefly deposed his father for having submitted, in 1176, then was killed by his father with Norman aid. Diarmait himself was then killed by another Anglo-Norman lord at peace talks in 1185. His second son, Domnall, was referred to in sources not as ‘king’ but as ‘prince’ of Desmond, but also began the tradition of using ‘MacCarthy Mór’ as his title. He had a formal inauguration ceremony at one of the clan’s many fortresses, always with hereditary clan lieutenants, O’Sullivan and O’Donoghue, in supporting roles. He defeated the English and temporarily drove them out of the southwest of Ireland in 1196, but failed to unify with the other native princely power, the O’Briens.

The Anglo-Normans were soon back and the next centuries saw the reduced princes of Desmond fighting against them, against the O’Briens, against local vassal families like the O’Mahonys, and of course amongst themselves, often uncle-nephew. The first of the junior branches, Carbery (Cairbreach), split off in about 1205, with the lords of Duhallow in the next generation (and several other minor branches). The various branches intermarried a lot, but they also married quite a bit with their Anglo-Norman neighbours, especially the FitzGeralds, earls of Desmond, but also the FitzMaurices, lords of Kerry. One more junior branch was forged about this time and moved to Scotland in service of the Bruce family—their name evolved into Macartney, and they returned to Ireland during the Scottish settlement of Ulster in the seventeenth century (becoming lords of Lissanoure in Antrim). In the 1790s, George Macartney famously led one of Britain’s first embassies to Imperial China—he was created Viscount Macartney at the start of his mission (1792), then raised in rank to Earl Macartney (in the peerage of Ireland) when he finished (1794). This title was short-lived and died with him in 1806.

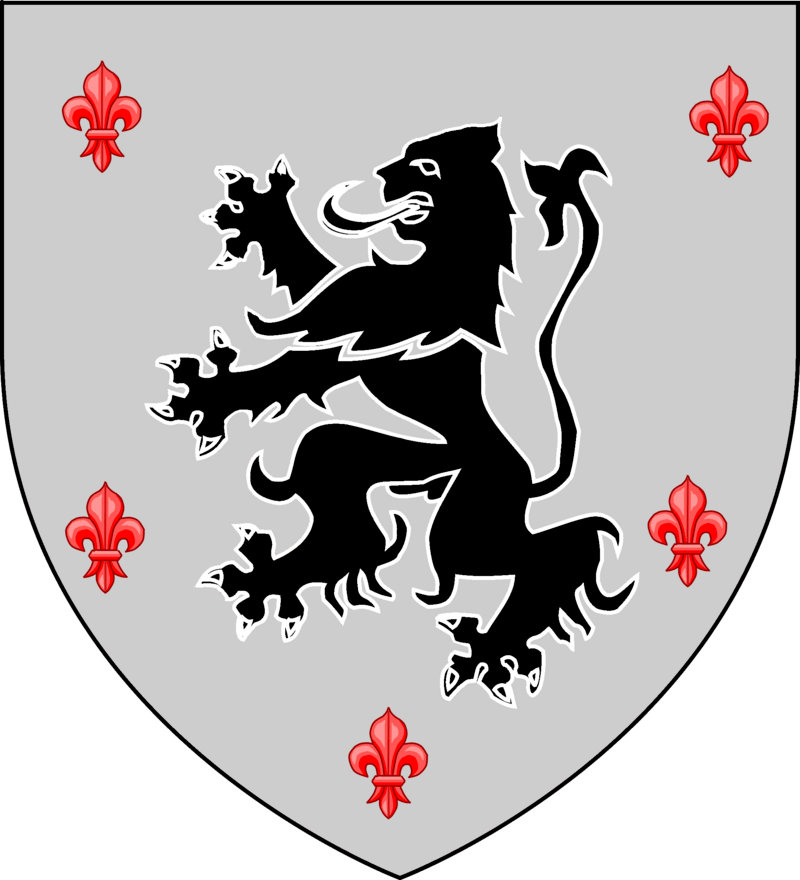

The difference between the Carbery and Duhallow branches was that the former was nearly as powerful in land and followers as the overall head of the clan, and used the title prince, or ‘MacCarthy Reagh’ (or ‘Riabhach’, which means ‘grey’ or ‘swarthy’), whereas the head of the Duhallow clan remained firmly loyal to the MacCarthy Mór.

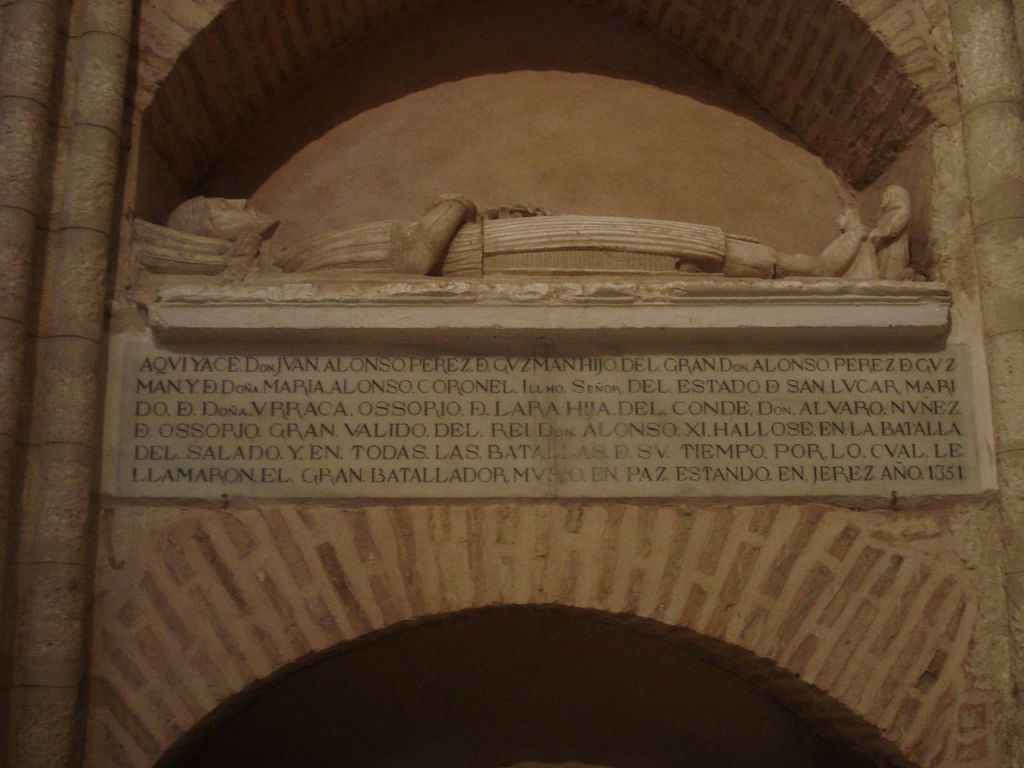

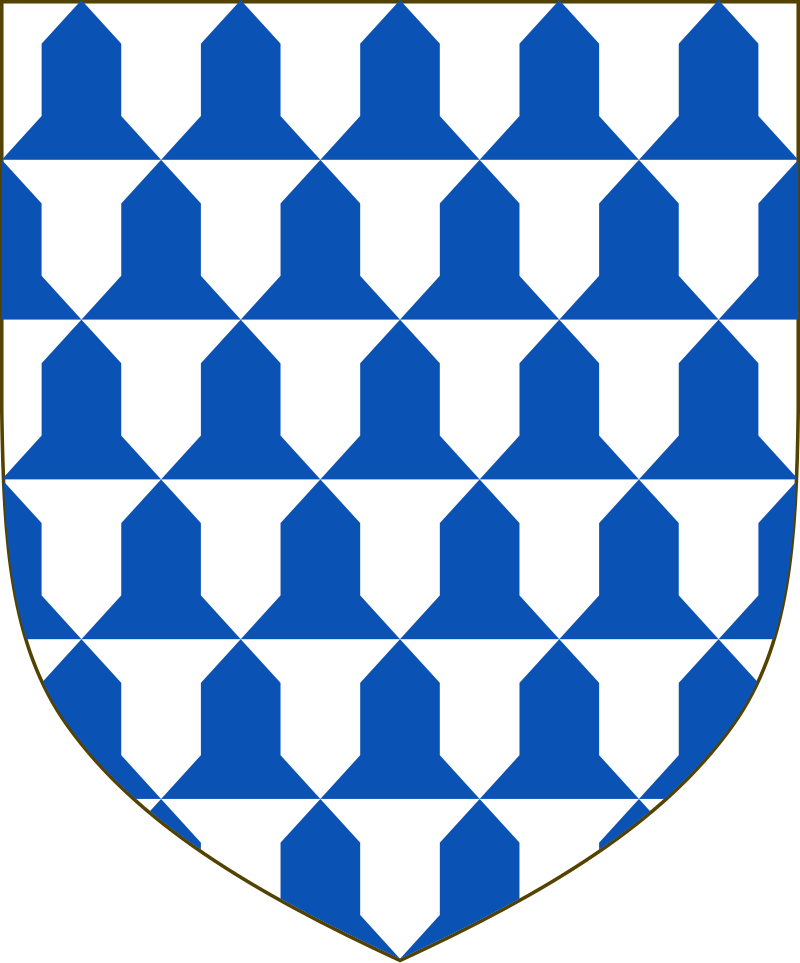

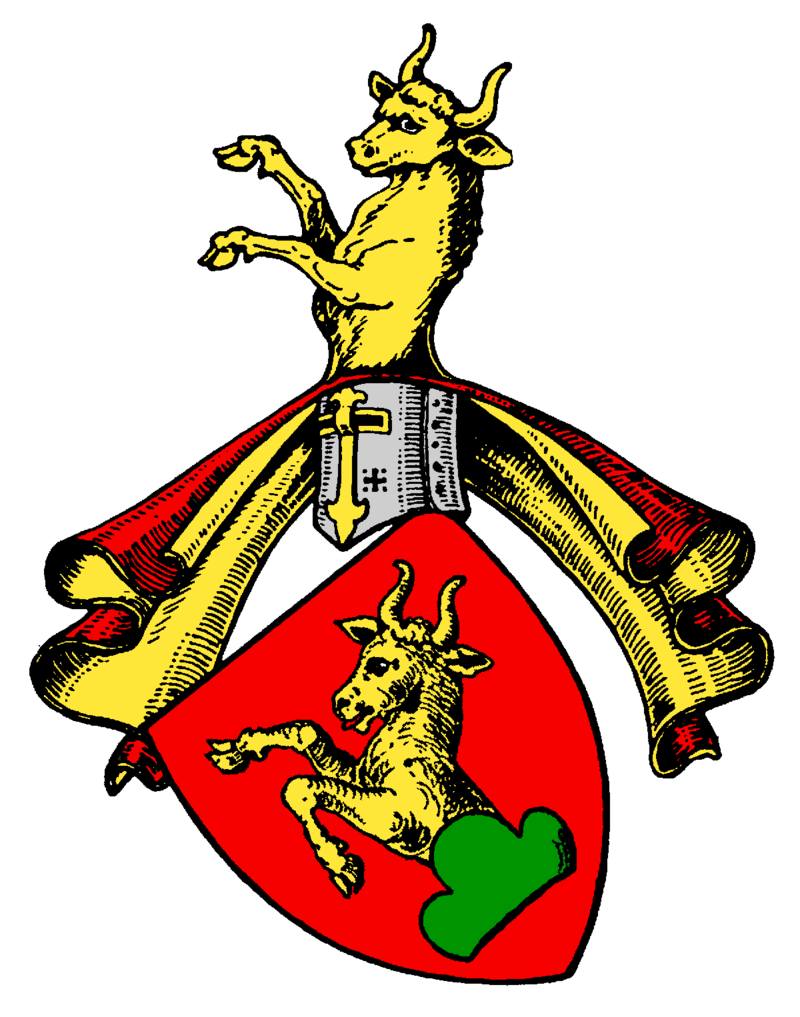

Donal Roe, MacCarthy Mór and Prince of Desmond, began a century of strength from about 1262. He acknowledged the English king as overlord but was able to regain MacCarthy authority over the Norman lords in Cork and Kerry. His grandson Cormac and great-grandson Donal Oge were the last real independent princes, and were brought down in part by trying to reimpose their authority on junior branches of the family, who, in resistance, allied with the Fitzgeralds. Yet another junior branch, this even more powerful than the others, was established by Donal’s brother Dermod, who in about 1353 was recognised by the English king (or his viceroy in Dublin) as Prince of Muskerry (sometimes Anglicised as Muscry), centred on the river Lee in central County Cork, named for the Múscraige people. We will return to their story below after the main line.

Donal Oge (‘the Younger’) was the last of the great princes of Desmond. His son, Tadhg ‘the Monk’ retired to a monastery in Cork, leaving his grandson Donal Oge III to attempt once more to revive the family’s power. He is the last to be called ‘king’ in the Irish sources. He rebelled against English rule in 1460 and was brought back in line through gifts and spent the rest of his reign rebuilding the family monastery at Irrelagh (today known as Muckross) and his residence at ‘the Pallis’. I’ve not found out much about Pallis Castle (or Caislean ua Cartha, ‘the Carthy Castle’) other than it was completely destroyed during the invasion of Oliver Cromwell in the 1640s. It was a short distance northwest of the town of Killarney which served as a sort of capital of the principality of Desmond (today in County Kerry). The abbey, on the other side of Killarney, is also today a ruin, having been dissolved as a religious house in the Elizabethan era. Nearby was the other seat of the MacCarthy Mór, Castle Lough, on a peninsula overlooking Lough Lein (also called MacCarthy Castle in some sources), now a ruin in Killarney Park.

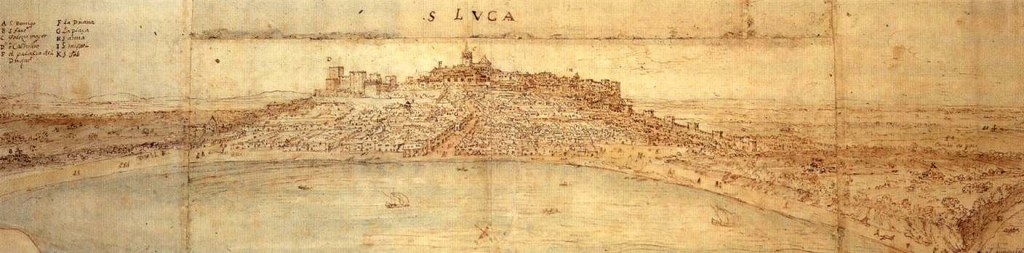

After nearly a half century of struggles both internal and external to the clan, in 1536, Donal an Druimin made peace with the Lord Deputy of Ireland, Thomas Radcliffe, and ruled peaceably as Prince of Desmond until 1558, when his son Donal, succeeded to the chieftaincy without fuss and submitted to the regime of Queen Mary—in return he was created Earl of Clancare (or Clancarty) and Baron of Valentia in 1565, and even went to England to be invested with these titles personally. Valentia refers to an island off the west coast of the Iveragh Peninsula in County Kerry—jutting out into the Atlantic Ocean. The English form of the name is a corruption of Bhéil inse, ‘harbour of the island’).

The first Earl of Clancare was a good Elizabethan, known as a poet and courtier. He married Honora Fitzgerald, daughter of the Earl of Desmond—from the family that had been the MacCarthy rival for centuries. Then in 1569, he renounced his English titles and joined his father-in-law in a rebellion against the Crown. He was soon knocked out of the war, however, by the forces of the Lord Deputy. In about 1587, his son Tadhg died, leaving the MacCarthy Mór with no close male heir. His daughter Elena married the following year the tanist of the Prince of Carbery, Finghin MacCarthy, who assumed the headship of the dynasty after his father-in-law Donal died in 1596. Finghin (known as ‘Florence’ in English sources) took the title MacCarthy Mór, but was challenged by his wife’s illegitimate half-brother, Donal, as well as by Dermot MacDonough, Lord of Duhallow, and Cormac, Prince of Muskerry.

Donal was recognised by the O’Neill rebels in the north of Ireland in 1598 and chased the Earl of Essex out of Munster; then Finghin came to Ireland in 1599 from England where he had been living at court with his wife since the 1580s and gained Elizabeth I’s favour. The English Crown agreed to recognise Finghin as the MacCarthy Mór in exchange for him subduing his rebel cousin, Donal. To attempt to counter this, Donal submitted to George Carew, Lord President of Munster, who pleaded on his behalf to the Crown. Meanwhile, the Lord of Duhallow, Dermot MacOwen MacDonough, also claimed the headship of the Crown, so Elizabeth sent an order to recognise his cousin and rival as head of his own subclan (also in dispute—so this is a rivalry within a rivalry), and in 1600 recognised Finghin again as head of the family—Dermot became an outlaw and soon joined Spanish plotters against the English government in Ireland. The Queen suddenly grew suspicious of Finghin for negotiating a peace settlement with Clan O’Neill in 1601—which for some reason was seen as treachery—and imprisoned him in the Tower of London. Here he stayed, off and on for nearly forty years! The ceremonial rights of the head of the clan (and the chief rents from vassals) were now vested in the Crown, while Donal was granted his father’s lands in 1605—these were lost by his son during the Cromwellian invasion of Ireland, and the MacCarthy Mór estates dissipated. Desmond was finally united as one county—both the principality and the earldom.

One of the newer castles built during this struggle was Kanturk Castle, built as a fortress for the MacDonough MacCarthys of Duhallow. Their lands were in the northern parts of County Cork, taking their name from Dúiche Ealla, the land of the river Allow. Kanturk, or Ceann Toirc (‘boar’s head’) was built on this river in about 1600 to defend against the ever-increasing number of English settlers—though it grew so large that the settlers obtained an order from the English authorities to halt construction by 1620—it was never completed. This still impressive fortress today belongs to An Taisce, the National Trust for Ireland.

Jumping back to look at the line of the princes of Carbery, we see that they too had many splits early on, and most princes died bloody deaths. The first prince, Donal Gott, was killed in 1251; his eldest, Dermod, was excluded from the succession but given lands on the southeast coast of Carbery to transmit to his descendants, who took the name Clan Dermod of Cloghane. These emigrated to France in the late seventeenth century and founded a mercantile enterprise in Bordeaux which persisted into the nineteenth century and beyond. Like several other branches we will encounter below, they were created (or at least called) ‘Count MacCarthy’ in France. The most prominent, Denis, served as director of the Chamber of Commerce of Bordeaux in 1767, then Premier Consul of the city in 1767-68.

The 1st Prince of Carbery’s younger sons ruled in succession: Finghin ‘Ragh na-Roin’ defeated the Geraldines in 1261 and secured Irish independence in the region, then was killed by the De Courcys later that year at Ringrone (Ragh na-Roin—many of the Irish princes are known to history after the place of their death). His brother Cormac was killed by the Burkes a year later, leaving Donal, who took his revenge on the De Courcys in 1295. His son Donal Caomh (‘the Handsome’) was the first to use the title ‘Prince’ and established that Carbery was de facto independent of the MacCarthy Mór—taking the clan title MacCarthy Reagh. Importantly, he controlled the ports along the south coast, and his heirs soon became the richest princes in Ireland. His son Donal Glas is recognised as ‘prince’ in charters from the King of England. This prince rebuilt the Friary of Timoleague as this branch’s ecclesiastical seat—this ancient religious site, dedicated to the sixth-century Saint Molaga (Teach Molaga is ‘House of Malaga’). Secularised in the 1580s, the Friary was briefly re-opened by local Catholics, but again closed by the end of the 1620s and eventually crumbled into ruins.

Not only did this branch of the family have its own friary, it also had its own bishop: Rosscarbery (or just Ross), on the south coast, created as a separate diocese in the twelfth century. Since 1958 the Catholic diocese has been united with that of Cork. Further east along the coast was one of the main seats of the MacCarthy Reagh, Kilbrittain Castle. Said to be the oldest still inhabited castle in Ireland, it as built in the 1030s as the seat of Clan O’Mahony; taken by the De Courcys, then by the Prince of Carbery in the early fifteenth century. After the family was dispossessed in the seventeenth century, Kilbrittain was held by the Earl of Cork (Richard Boyle) and then the Stawell family who restored it and enlarged it over two centuries. It remains privately owned.

In the 1480s, another Finghin, Prince of Carbery, gained the favour of King Henry VII who commissioned him to receive the homage of the other Irish chiefs on behalf of the Crown. He went further in 1496 and surrendered his lands and sovereign rights (as ‘MacCarthy Reagh’) for regrant, which thus permitted him to adopt primogeniture for his lands, with the approval of the Geraldines—one of whom was his wife, and one his daughter-in-law (the latter in particular was daughter of the Earl of Kildare, Lord Deputy of Ireland). Yet his son Donal joined with his cousin the Prince of Muskerry and rebelled against Henry VIII in 1521, and defeated his mother’s kinsman, the Earl of Desmond. His sons, Cormac, Finghin, Donogh and Owen thus all reverted to the system of tanistry and ruled in succession as princes of Carbery.

Their descendants split: Owen’s son Finghin joined the O’Neill rebellion of the 1590s and was one of the last to submit in 1602—his issue, the MacCarthys of Timoleague moved in the 1690s to France, like so many MacCarthys, and acquired lordships near La Rochelle on the Atlantic coast. Charles-Denis MacCarthy was a Captain in the Regiment-Royal of Dragoons for the King of France, and in 1786 was recognised as ‘Vicomte MacCarthy’ and given honneurs de la cour (the right to attend court at Versailles). This line died out in the early twentieth century.

The son of Prince Donogh was Finghin MacDonough who became the next MacCarthy Mór, as above, so we’ll pick up his line again. The son of Prince Cormac, Donal na-Pipi (‘of the Pipes’—named for the pipes of wine that washed onto his shores) succeeded as MacCarthy Reagh in 1593. He renounced the princely title (again) and was created Lord Carbery by James I in 1606. He had many sons: the descendants of the eldest, Cormac, remained titular princes of Carbery. One, Donal, was High Sherriff of County Cork in 1635, the next, Cormac, was commander of the Munster clans in the rebellion of 1641. His estates were confiscated by Cromwell in 1652, and partially restored by Charles II—he had served in the Duke of York’s regiment in France during the Commonwealth era, which established a link for his sons and grandsons who fought for James II in the Glorious Revolution of 1688-89 and at the Boyne in 1690. One of the daughters, Eleanor, went into service of Queen Mary of Modena in her exile at Saint-Germain in France. A cadet branch also moved to France at this time to live freely as Catholics, and settled in Toulouse. The Toulouse MacCarthys were also created counts (1776) and given the honneurs de la cour. In the next generation, the Abbé MacCarthy was a famous preacher in France in the 1820s, while his brother served as aide-de-camp of the Prince of Condé. The head of this branch, titular prince of Carbery, emigrated to the United States in the 1840s, where they still have descendants.

Meanwhile, Finghin MacDonough MacCarthy, titular MacCarthy Mór, spent much of his ‘reign’ in the Tower of London—in and out on various suspicions and bails and fees—as did his eldest son, Tadhg. While living in London, Finghin (or Florence) compiled several annals of Irish medieval histories as Mac Carthaigh’s Book, a valuable resource held today in Ireland’s National Library.When he died in 1640, his younger son Donal succeeded to the now empty title, became a Protestant and served the Duke of Ormonde as a royalist commander in the Civil Wars; his brother Finghin meanwhile was a rebel and held County Kerry for the Irish Confederation from 1641. Of the descendants of Donal, Cormac served the Crown as a lieutenant for James II and governor of Carrickfergus Castle (outside Belfast), but his heirs remained Protestant and in Ireland (as opposed to those Catholic MacCarthys who emigrated to France). Another Cormac, or ‘Charles’, was the last to use the title ‘MacCarthy Mór’. He was a captain in the Royal Guards regiment and died in 1770. His first cousin John MacCarthy added his mother’s surname Welply to his own—her father, Joseph Welply, was a Welshman who had moved to Cork and acquired some of the confiscated lands of the MacCarthys of Muskerry from the Crown. John may have tried to claim the title MacCarthy Mór at this time. A few generations later, another John Welply MacCarthy emigrated in the 1840s to the United States.

Some of Finghin MacDonough MacCarthy’s descendants moved to France with James II after he was deposed in 1688-89. One of these, Charles, a captain in the French army, may have been a claimant to the MacCarthy Mór title, and may have left descendants in France.

But the more famous French MacCarthys came from the line of Muskerry, so we need to back up one last time and look at this branch. The princes’ main fortress was at Macroom, while the tanist was usually based at Carrignamuck. Macroom was a town on the river Sullane, a tributary of the Lee west of Cork City. It was a prosperous town due to milling, and was thus defended by a number of MacCarthy tower houses. Macroom became the capital of the Muskerry princes in the fourteenth century. Its castle, in the centre of town, had originally been built in the twelfth century; was significantly enlarged in the mid-sixteenth century, then lost to the MacCarthys in the 1690s. Only a ruined tower and a wall remains of the old castle, while an elaborate gatehouse crowns the town’s main square—though this was built in a gothic style only in the 1820s.

One of the MacCarthy tower houses was Carrignamuck, east of Macroom about halfway to Cork. Built in the 1450s, Carraig na Muc (‘rock of the pigs’) was forfeited by the MacCarthys in 1641 and a ruin by the late nineteenth century. It is in private hands today, in the grounds of the eighteenth-century Dripsey Castle. Another of these tower houses, this one to the west of Macroom, was the delightfully named Carrigaphooca, whose name ‘rock of the fairy’—and this strategic road towards Kerry is sometimes called ‘fairyland’ (more on the fairies below).

The 9th Prince of Muskerry, Cormac Laidhir (‘the Stout’), added even more to this string of fortifications west of Cork, including Kilcrea Castle and the most famous of them all—Blarney Castle. He also founded a Franciscan abbey at Kilcrea in 1465—so each of the three main branches of the family now had their own ecclesiastical centre.

Blarney Castle, about five miles northwest of Cork, was first built in the early thirteenth century. The Prince of Muskerry significantly enlarged it in the 1440s, and added the battlements which include the famous Blarney Stone. Also known as the ‘Stone of Eloquence’ it is thought to once have been an ancient coronation stone—common across the Celtic world—or a charmed stone gifted to Clan MacCarthy by the goddess Clíodhna. One version says this ‘fairy protectress’ of the clan granted an eloquent tongue to the builder of the castle, whose words later believed to be simply empty flattery or ‘blarney’. Tourists now kiss the blarney stone to be blessed with this gift too. Like most of the MacCarthy properties, Blarney Castle was confiscated in 1641, restored in 1660, then confiscated again in the 1690s. This time it was sold (eventually) to the powerful governor of Cork, James Jeffreys, and it stayed in his family for two centuries. A new Blarney House was built nearby, which burned down in the 1820s. The estate passed to the Colthurst family by marriage in 1846, and another house was built—this remains the seat of this family of baronets.

Later in his reign, the great builder Prince Cormac ‘the Stout’ allied with Henry VII in 1494 in an attempt to pacify the region, but soon after quarrelled with his brother and tanist, and was murdered. This meant the brother’s lineage was excluded, so the succession passed to Cormac’s son Cormac Oge Laidhir (‘the Younger Stout’!). He defeated the Fitzgeralds at Mourne Abbey in 1521, which eventually became part of his family’s properties when the Abbey was secularised under Henry VIII.

The 11th Prince of Muskerry, Tadhg, agreed to submit to English justice in 1542, repudiating the traditional Irish system of Brehon law. His brother was the 12th Prince, according to tanistry, and was succeeded by his sons, Sir Dermot and Sir Cormac, who both worked with the English government to suppress dissent—just as the region was heating up again with the rebellion of the Earl of Desmond. Cormac, the 14th Prince, was named Sheriff of County Cork and given the power of martial law in 1576; he formally surrendered his lands and titles in 1578, and was re-granted them by the Crown (including Mourne Abbey, and Cloghan in Carbery, confiscated from his kinsman). Despite the official ending of tanistry with the surrender and regrant, he left a will naming his brother then his nephew then his son—a clear indication the old ways were still in his mind. He died in 1583, and his brother Callaghan, who didn’t want any trouble, quickly surrendered the title to his nephew.

Cormac, 16th Prince of Muskerry, officially Baron of Blarney in the Peerage of Ireland, was, like so many others, a claimant for the title MacCarthy Mór in 1596. He perhaps hoped to improve his chances of being recognised by the English Crown by conforming to the Protestant Church of Ireland, and to be on the safe side, repeated his father’s act of surrender and regrant in 1589; then again for King James in 1614. He was also for a time Sheriff of Cork, and stayed loyal to the Crown during the siege of Kinsale, October 1601, when many of his kinsmen went into rebellion and then exile. Yet he was accused by a cousin of corresponding with Irish rebels and their Spanish supporters, and was taken into custody. He was forced to give up Blarney Castle, then Macroom—he escaped and soon came to terms with the government, 1602, and died peaceably in 1616.

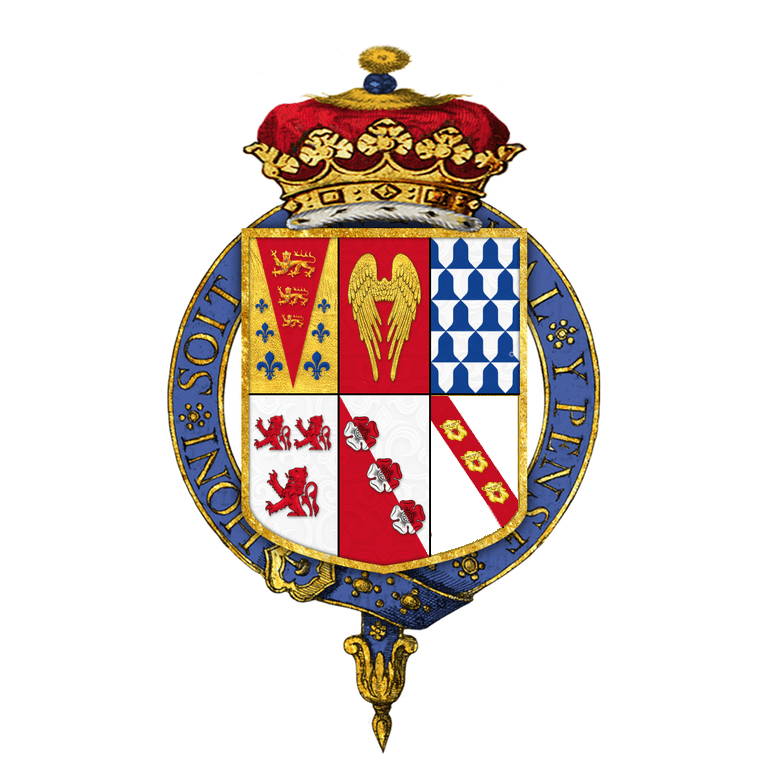

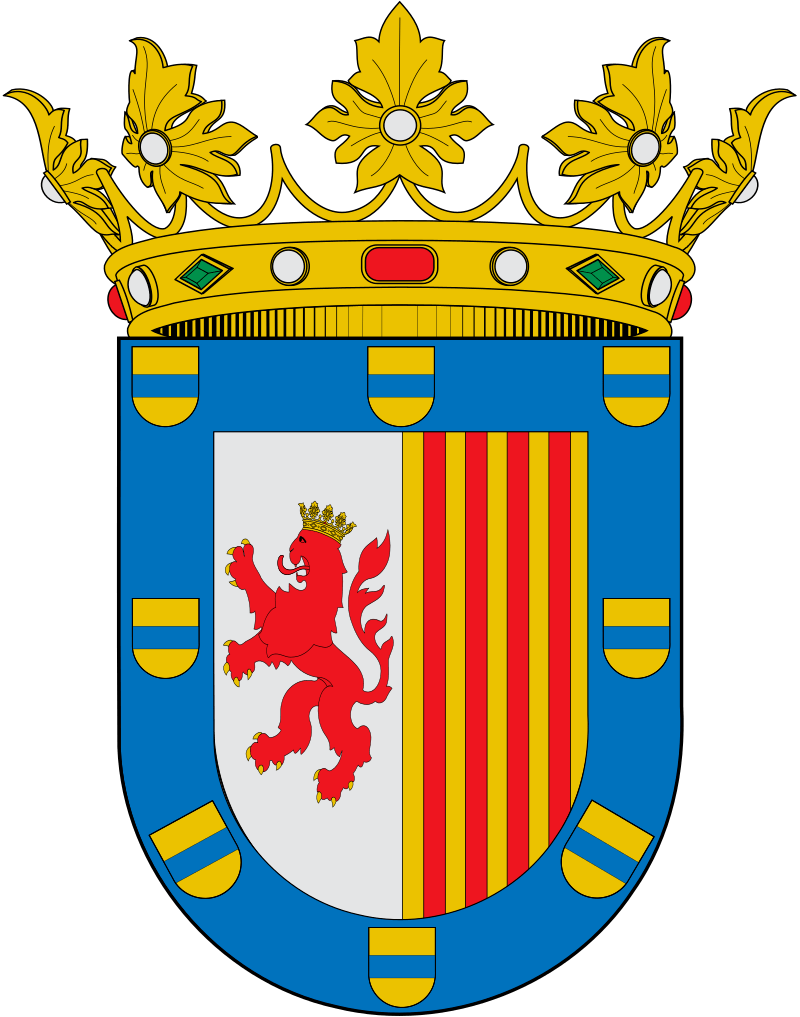

Ever the most loyal branch, Cormac’s son Cormac Oge, aka Sir Charles MacCarty (as it was usually spelled in this century), was created 1st Viscount Muskerry in 1628. His son Donough, the 2nd Viscount, was then named Earl of Clancarty in 1658. He had been a leader of the Irish Confederation and commander of its Munster forces, 1641, but soon sided with Charles I and was appointed Lord President of Munster. After the execution of the King in 1649, he tried to keep the southwest loyal to the Stuarts, but by 1652 surrendered Limerick to Ireton. His last stronghold was Rosse Castle near Killarney, which was the last place to surrender to Parliamentary forces—his lands were confiscated and he was tried for treason, but he fled abroad to join the court of Charles II. He was created earl in Brussels, and after the restoration of 1660, was restored to his lands. It seems he put forward a request once again to be recognised as MacCarthy Mór, but the time of traditional Irish chieftaincies was over. He died in 1665 in London.

His eldest son Charles had been killed a month before at the Battle of Lowestoft against the Dutch, and his infant grandson Charles (nominally the 2nd Earl of Clancarty) died within the year, so the 3rd Earl of Clancarty was Callaghan, who had initially become a monk while in exile in France, but now renounced his ecclesiastical position, became a Protestant to succeed to the title and to marry Elizabeth FitzGerald, daughter of the 16th Earl of Kildare, then re-converted to Catholicism on his deathbed in 1676.

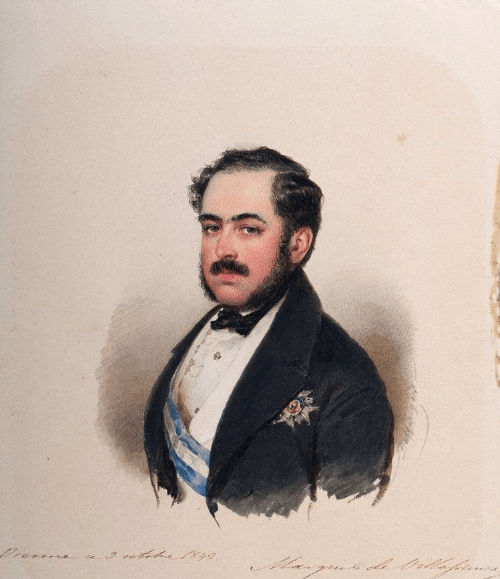

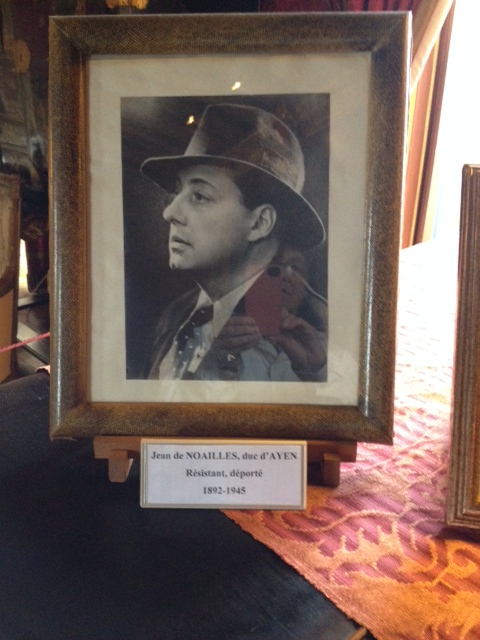

It was the younger son of the 1st Earl, Justin, who became the most famous MacCarthy of the early modern era. As a boy he went into exile in France with his family, and was raised by soldiers there, coming into contact with James, Duke of York and becoming a close friend. As nephew of James Butler, the 1st Duke of Ormonde, he was well connected during the Restoration period, though he stayed in France until the late 1670s, when he returned to try to help defend the Duke of York’s cause against those who would exclude him from the royal succession due to his Catholicism. When James did become king in 1685, McCarthy (the preferred spelling for him) was named Lord Lieutenant of County Cork, 1687, and member of the Irish Privy Council. He kept Munster loyal to James during the Glorious Revolution and was named Master-General of Artillery of James’ troops in Ireland, then escaped with his regiment to France. In 1689 he was created Viscount Mountcashel and Baron Castleinch (or Castle Inchy, in County Cork); then soon after (1690 or perhaps 1693?) he weas elevated to a dukedom, either of Clancarty, or, as seen in French sources, ‘Duc de Mountcashel’, taking its name from the ancient Rock of Cashel upon which the MacCarthy dynasty was anciently founded. None of these titles were of course recognised in England, but they were in France, and he was honoured at the court of Louis XIV, who named him commander of all Irish troops in France in May 1690. His Mountcashel Brigade of about 5,000 men was sent to fight in Piedmont then in Catalonia in 1691 against the King of Spain, and finally to the Rhine in the campaign of 1693 against the Holy Roman Emperor. The Duke of Clancarty died a year later taking the waters at Barèges in the Pyrenees, and was buried there. He left his (ephemeral) ducal title to his cousin from the Carrignavar branch (below).

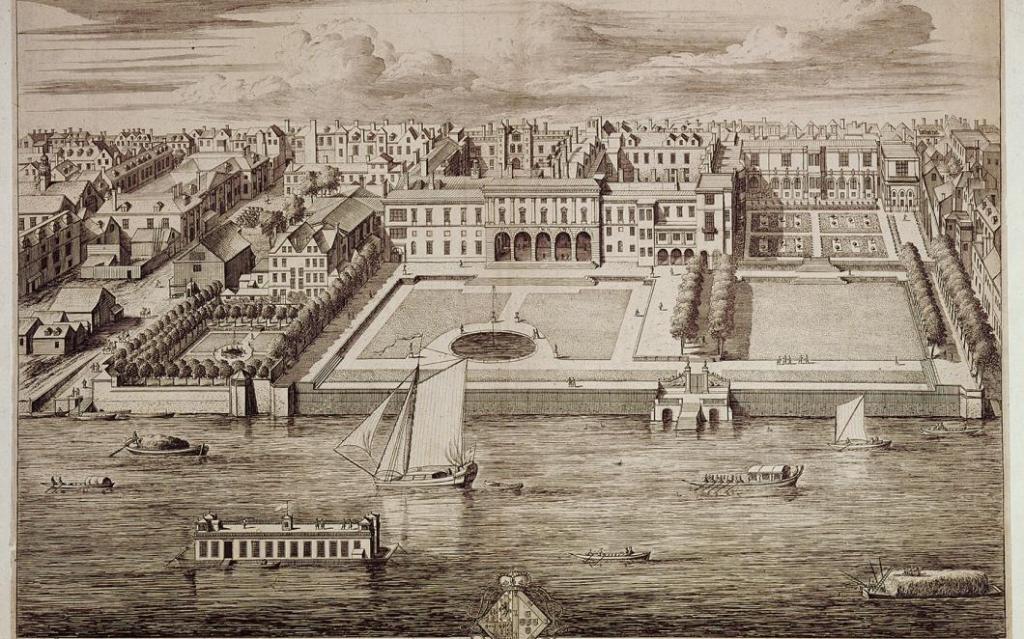

Meanwhile, Lord Mountcashel’s nephew Donough carried on the senior line as 4th Earl of Clancarty. During his period as head of the family, he built a new mansion next to the old Blarney Castle, and also made improvements to Macroom. He married into the Spencer family, allied to the Marlboroughs and other families in favour at court, but his star began to wane when, despite being raised a Protestant, he adopted the Catholic faith of his fathers in 1689 and was taken to the Tower and his titles attainted. He escaped to France in 1694 where James II appointed him Captain of his Horse Guard. But in 1697, he abandoned the cause and returned to Ireland, only to find himself imprisoned again and his lands confiscated again. He went abroad and settled in the Low Countries and in Hamburg, and though his attainder was reversed in 1721—or at least promised—he did not return and died in Germany in 1734.

His son Robert, known as ‘Viscount Muskerry’, was, like his father, in favour with those in power in London, notably the Earl of Oxford and the Duchess of Marlborough. Yet they could not convince the Crown to return his lands (or indeed confirm the reversal of the attainder of his earldom), though he did obtain a senior naval post as Commodore-Governor of Newfoundland, 1733-34. The titular 5th Earl of Clancarty ultimately gave up trying to reclaim his lands (it was simply too complicated as they had already been redistributed to others, notably the Bentinck earls of Portland), and in 1740 he resigned his commission in the Royal Navy and joined the Jacobites in France, where Louis XV granted him a post and a pension. He settled into a château on the outskirts of the town of Boulogne (on the English Channel) and died there in 1769.

His successors are not well known. They served in France’s armies until at some point they returned to Ireland, probably in the early nineteenth century. Donough McCarthy called himself the titular ‘Earl of Clancarty’ until his death in 1871. His heirs emigrated to America.

A bit more is known about a cadet branch of the MacCarthys of Muskerry, those of Carrignavar, who stayed in France. Florence Callaghan McCarthy was adopted by his cousin Justin McCarthy, Viscount Mountcashel, in his will of 1693, so in 1694 he took the title 2nd Duke of Clancarty in the Jacobite Peerage. He died in 1715, and was succeeded by his son, Callaghan. The 3rd Duke of Clancarty was an officer in the Irish Brigade in France, and was killed fighting for Louis XV at the Battle of Fontenoy in 1745. The 4th Duke was a French naval officer, killed at sea; while the 5th Duke served in the Napoleonic campaigns in Spain. His son the 6th Duke lived until 1903. All three of these dukes were named Florence. I know very little else about them (and the ducal title does not appear on lists of French dukedoms of the nineteenth century, even those recognised though created by foreign rulers), so would love to hear from people with more information!

Finally we have Pol (or Paul), the 7th Duke of Clancarty (or Clancarty-Blarney). He had been a lieutenant in the army of Napoleon III as a young man in 1870s. He sometimes used the title ‘Prince of Desmond’ and stressed his rights to be seen as the head of the royal house of Munster, heir to the ancient king-bishops of Cashel. He died in his eighties in 1927 with no male heir, and any such claims died with him.

There were other MacCarthys in France in the nineteenth century. The line of Coshmaing, initially based along the river Maine (Maing) [Coshmaing = Castlemaine] with their seat at Castle Molahiffe, settled in France and by the end of the eighteenth century were highly ranked in the Life Guards of Louis XVI. The son-in-law of the last of these, Charles Guéroult, took the name MacCarthy and served in the army of the French noble émigrés during the Revolution, then joined the British army, and in 1812 was named Lieutenant-Governor of a fort taken from the French on the Senegal river. In 1814 he was transferred to the same post in the British colony of Sierra Leone, then in 1821 was named Brigadier General of the West Coast of Africa, in which capacity he helped to turn the Gold Coast into a Crown Colony (Ghana), suppressing its slave traders. General MacCarthy was killed in battle against the Ashanti in 1824.

Does anyone today claim the titles MacCarthy Mór, MacCarthy Reagh or Prince of Muskerry? There were several genealogical studies published in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, but none of these was conclusive. The senior branch by the twentieth century was determined to be the MacCarthys of Kerslawny (also known as the Srugrena sept or the sept of Coraic of Dunguile, or more recently as the Trant-MacCarthys), based near Killarney. This branch broke off from the main line back in the early fifteenth century. Their position as the senior line was recognised by the Ulster King of Arms in 1906 (after the death of the last of the MacCarthy counts of Toulouse), but after Ireland became a republic things became a bit murky. In 1992, a claimed relative of the MacCarthy recognised in 1906, Terence MacCarthy, a genealogist from Belfast, claimed the title MacCarthy Mór (as ‘Tadhg V’) and presented genealogical documents later shown to be false. He was recognised by the Irish Genealogical Office, a government division that recognised clan chiefs, and he set about organising an organisation of clan groups and created an order of chivalry—and even started handing out noble titles. In 1999, The Sunday Times exposed his fraud and he withdrew the claim—the scandal led to the ending of the practice of the Irish government to get involved at all in the regulation of clan titles, in 2003.

Various family associations today state on their websites that there is no recognised head of the clan, or anyone holding the titles prince of Carbery or prince of Muskerry, and has not been since the death of the last MacCarthy Reagh claimant in 1754. One of these association websites decries the former practice of the Irish government to base its recognitions of clan chiefs based on the principals of primogeniture, when, according to older customs of Brehon law and tanistry, if there is no clan chief, the family as a whole should organise a meeting to choose one, a Derbhfine. One candidate seems to be from the line of Kilbrittain (Carbery) living in Canada. The most recent postings suggest there is a meeting happening this spring with an election expected in August 2025. Watch this space!

(images from Wikimedia Commons and other public spaces)