The city of Manchester was a rough city in the industrial age. The history of the dukes of Manchester shares some of the underworld aspects of the great northern powerhouse, but in fact has nothing to do with the city—like most British dukedoms, the title does not align with the geography. Three modern dukes of Manchester have spent time behind bars—but the long history of their family is much more interesting than that.

The Montagus were known in the Middle Ages as the earls of Salisbury, powerful magnates in the west of England and often very close to the Crown. A secondary branch of Montagus—perhaps not related at all, but certainly claiming to be (as we shall see)—built up their powerbase not in Somerset but in Northamptonshire, in the Midlands. At the start of the eighteenth century, the senior line obtained the first family dukedom, Montagu (1705), while the junior lines had already established themselves as earls of Manchester (1626), earls of Sandwich (1660), and eventually earls of Halifax (1714). The dukedom carried on, but passed into an allied family, the Brudenells, then went extinct in 1770. Meanwhile, the earls of Manchester were given the family’s second dukedom, of Manchester (1719), which continues to this day. Other interesting side-branches of the House of Montagu are the Wortley-Montagus, famous for its Enlightened women in the eighteenth century, and the Montagus of Beaulieu, famous for the National Motor Museum and a gay sex scandal of the 1950s—though their story belongs more to the story of the dukes of Buccleuch, whose surname is Montagu-Douglas-Scott; these became Montagus only by marriage so will have their own blog, under Scott.

As with many families, the Montagu family in all its branches is held together by a shared heraldry: the three distinctive red diamonds are known as ‘fusils’. This was later quartered with the arms of Monthermer, a very distinctive green eagle, and junior branches added small symbols as they became established: a red crescent, a red star, and so on. The name, initially spelled Montaigu, Montague or Montacute, is from the Latin monte acuto, or ‘pointed hill’.

Some have tried to trace the surname to the Norman village of Montaigu-les-Bois in Coutances—and there was a French noble family with this name, which died out in 1715—and that a companion of William the Conqueror, Drogo, came from there and gave his name to estates he was granted in Somerset after the Conquest. Others, however, suggest the opposite, that he took his surname from these estates, for a priory dedicated to Saint Michael on a ‘pointed hill’ (Mont Agud), near Yeovil in eastern Somerset. Historical records show that this area of the county had initially been granted to the Count of Mortain, half-brother of the Conqueror, and that the Norman nobleman named Drogo was in his suite and became his vassal for about twenty fiefs in Somerset and Devon. Two of the key estates he was given in Somerset were at Tintinhull and Wincanton, near Bruton, a bit to the northeast. The latter included Knowle Park, held directly from the King. Also nearby was Shepton Montague. These all passed to the Neville family in the 1420s.

Montacute Priory was founded in about 1080, a dependency of the Abbey of Cluny in France, and Montacute House was built nearby. The Priory was dissolved in 1539 and became a farmhouse on the Phelips estate: Sir Edward Phelips, a yeoman farmer who became Speaker of the Commons, rebuilt the house in the 1590s—one of the finest examples of the Elizabethan country house. But his family soon faded back into the rural gentry and found it hard to maintain such a grand house. Their distant descendants ultimately sold it in 1931, becoming one of the first properties acquired by the National Trust.

Meanwhile, the descendants of Drogo were summoned to Parliament as Lord Montagu or Montacute in 1299. Simon, the first baron, fought with Edward I and Edward II in Wales, Aquitaine and Scotland, and was named Admiral of the Fleet in 1310. His son William was Steward of the Household of Edward II in 1316 and Seneschal of Gascony in 1318. He thus established great intimacy with the Plantagenet kings, and propelled his three sons to the highest social, political and ecclesiastical positions in the land. William, 3rd Baron Montagu, was created Earl of Salisbury in 1337 and Marshal of England in 1338. His brother Simon was Bishop of Worcester, then of Ely; while Edward was also summoned to Parliament as Baron Montagu, 1348, having married Alice of Norfolk, a granddaughter of Edward I. They had only daughters, so a junior line was not established at this point.

The earldom of Salisbury had first been created in 1145 by Lady Matilda, at a time when she held power, as a reward to an ally for watching over the western parts of England, notably the Salisbury plain. The original line soon died out and the title passed through three heiresses until re-granted to William de Montacute in 1337. He had grown up as a close companion of Edward III, and solidified his position as a royal favourite when he helped the young king overthrow his mother and her lover Mortimer in 1330. Salisbury served with Edward in Scotland and in France, and frequently served as his representative in diplomatic activity. The King also recognised him as King of Mann, supporting his claim to rule that island due to a supposed grant given to his grandfather Simon by Aufrica de Connoght, whose identity is unclear, but may have been heiress of the last Norse king of Mann, Magnus Olafsson. But first the Earl had to conquer the island from the King of Scots, which he did in 1343, and he and his son were recognised as sovereign lords until they sold these rights to the Le Scrope family in 1392. Closer to home, the Countess of Salisbury is remembered in myth or anecdote as the woman whose honour was defended by Edward III when she dropped her garter at a ball (and thus the source of the name for his order of chivalry).

The main seat for the family at this point, to be closer to court in London or Winchester, was Bisham Manor, in Berkshire. A manor house was built here in the 1260s by the Knights Templar, whose properties were confiscated by the Crown in 1307; Bisham was then sold to the 1st Earl of Salisbury in 1335, who founded a priory next door to serve as the Montagu mausoleum. When the Salisbury dynasty ended, Bisham returned to the Crown under Henry VIII, who also dissolved and pulled down the priory in the 1540s. The manor was acquired by the Hoby family who held it for the next two centuries.

When the 1st Earl of Salisbury died in 1344, he was one of the wealthiest men in the Kingdom. His son William Montagu, 2nd Earl of Salisbury, was one of the first knights of the Order of the Garter, in 1348, and a military commander in the war in France. He married Joan of Kent, the King’s first cousin, though this was declared invalid; and his title passed to his nephew. John, 3rd Earl of Salisbury, was also heir to his mother, Margaret de Monthermer, heiress of the 2nd Baron Monthermer, whose father was the Earl of Gloucester and Hertford, and mother was Joan of England, daughter of Edward I. The origins of the Monthermer family are unknown and it is unclear where the name comes from (though likely Norman). As close kin and friend of King Richard II, the 3rd Earl fell from power with him in 1397, then was executed in 1400 for plotting against the new king, Henry IV. Thomas, 4th Earl of Salisbury, recovered the lands and titles in 1409, and swiftly gained the favour of Henry V, fighting alongside him in France in 1419 and given the County of Perche as one of the spoils of war. In 1423 he was named Governor of Champagne, as part of the English occupation of northern France, then was killed as one of the English commanders in the siege of Orléans, 1428.

Alice Montagu was left as her father’s heir—medieval earldoms could be inherited through women, so she was the 5th Countess of Salisbury in her own right, as well as Baroness Montagu and Baroness Monthermer. She had married Richard Neville in 1420 and they had several children: the elder sons were the earls of Warwick and Salisbury, while the 4th son, John, a Yorkist commander, was created Baron Montagu, 1461, then Earl of Northumberland in 1464 and Marquess of Montagu in 1470 (in exchange for giving up the Northumberland earldom)—only to lose all of this on the execution block in 1471. The earldom of Salisbury passed from the Nevilles to George, Duke of Clarence (brother of Edward IV), then to his son Edward, though only nominally since he was a prisoner in the Tower after the Battle of Bosworth Field. His sister, Margaret, Countess of Salisbury, is remembered as the cousin of Henry VIII that was dragged to the Tower as an old woman, and executed for simply having too much Plantagenet blood in 1541. Eventually, the earldom of Salisbury was recreated for the Cecil family (1605), and they hold it still today.

The medieval Montagu family was gone. But another emerged at about the same time, claiming that their branch’s founder, Richard Ladde, who took the name Montagu in 1447, was a son or grandson of John or James Montagu, an illegitimate son of the 4th Earl of Salisbury. Richard’s family certainly used the same coat of arms, so either this is true, or they assumed the name and arms due to a gift in the last Earl’s will. But the family has few connections to Somerset or Wiltshire: Richard was a yeoman from Hanging Houghton, and his son Thomas Montagu was of Hemington, both villages in Northamptonshire. Hanging Houghton, in the centre of the County, was a great country house, owned by the family since about 1470, with great gardens and terraces, though eventually abandoned by them in 1665. It was in ruins by the eighteenth century, and now just a footprint remains.

It was Thomas’s son, Sir Edward Montagu, who brought this family back to the top ranks of English aristocratic society. A lawyer, he became Chief Justice of the King’s Bench and of the Common Pleas (1530s-50), a member of the Privy Council, and in 1547 was named one of the sixteen executors of Henry VIII’s will and governor of the child-king Edward VI. He narrowly avoided execution in 1553 for having drafted Edward VI’s will naming Lady Jane Grey as heir instead of Princess Mary.

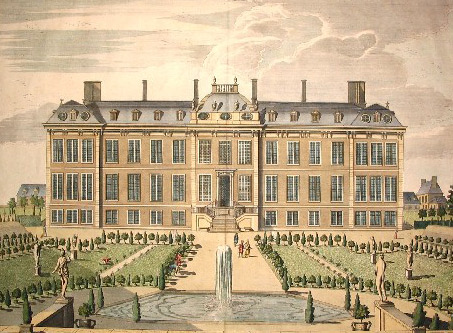

Sir Edward had moved his chief residence to Boughton, also in Northamptonshire, in 1528. There was a de Boughton family in this county since the early Middle Ages, with a manor house just north of the town of Northampton. The estate of Boughton, however, was further north, near the town of Kettering. Buildings here were part of a monastic complex that, when shut down by Henry VIII, was sold to Montagu. The grand country house we see there now was built by his great-grandson, Ralph Montagu, in the 1680s, inspired by his periods of residence in France and the newly built château of Versailles. John, 2nd Duke of Montagu, developed extensive gardens, again in a French style influenced by his Grand Tour (and giving him the nickname ‘John the Planter’). In the eighteenth century, however, Boughton House lost prominence, designated as a residence for dowagers or younger siblings, and, because it was not the family’s main residence, it was not renovated to keep up with the latest styles and therefore remains almost completely untouched in its original seventeenth-century form—a rarity amongst the English country houses. After 1790, Boughton was part of the inheritance of the dukes of Buccleuch, but continued to fade (since they resided primarily in Scotland), but since the 1990s, new life has been breathed into Boughton, particularly its gardens, and re-oriented towards tourism.

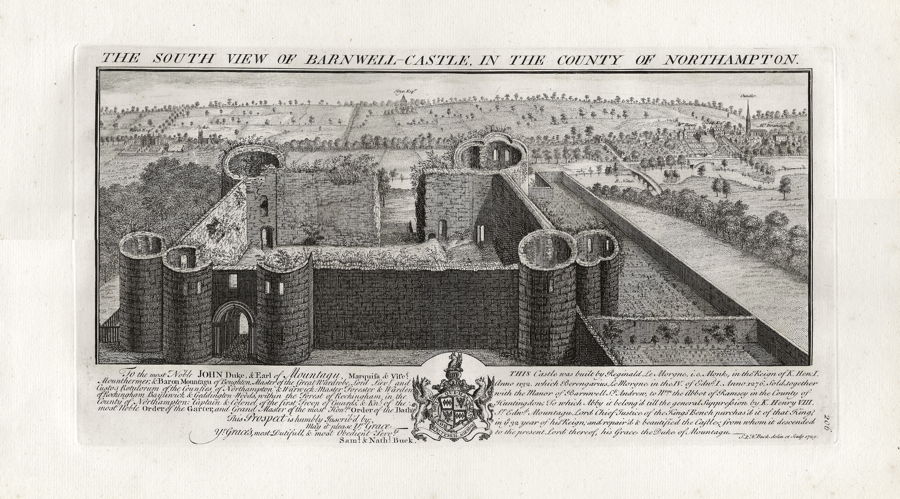

Chief Justice Sir Edward Montagu’s son Edward was an MP for Northamptonshire and held several posts in the county (including county sheriff four times). He expanded the family’s landholdings in this county even more, notably acquiring Barnwell Castle in the 1540s, to which he added a manor house—the Tudor house (and older castle ruins) passed to the dukes of Buccleuch in the early nineteenth century; they sold it in 1913, but it was purchased in 1938 by the 6th Duke’s grand-daughter and her husband the Duke of Gloucester. The Gloucesters—cousins of Elizabeth II—lived here until the 1990s and it was sold in 2024.

The second Edward Montagu died in 1602, leaving behind a set of sons who each rose to prominence in different ways. Three of them, Edward, Henry and Sidney, spawned the separate lines of Montagu of Boughton, Montagu of Manchester and Montagu of Sandwich. Of the others, Walter and Charles gained knighthoods and served in Parliament, while James entered the church and served the Crown as Dean of the Chapel Royal from 1603. He had Calvinist leanings and a scholarly reputation, so was close to King James, whose works he edited, and who promoted him to Bishop of Bath & Wells in 1608 then of Winchester in 1616. A Privy Councillor and first Master of Sidney Sussex College at Cambridge University, he died relatively young only two years later in 1618.

The eldest brother, Edward, an MP for Northamptonshire since the 1580s, was promoted to the House of Lords by the King in 1621, as Baron Montagu of Boughton. He remained a loyal servant of the Stuarts and when tensions arose between Parliament and Charles I, he backed the King and was arrested, 1642. The damp of the Tower of London made him ill and though he was transferred to a hospital, he died in 1644.

Meanwhile, his brother Henry had become a lawyer like their grandfather, and Chief Justice of the King’s Bench by 1616. King James named him Lord High Treasurer in 1620, and created him Viscount Mandeville and Baron Montagu of Kimbolton, then the next year raised him to the post of Lord President of the Council. King Charles continued his father’s favour and raised him in rank to Earl of Manchester, 1626, and Lord Privy Seal, 1628. Like his elder brother, he remained one of the most trusted counsellors of Charles I, but when he died in 1642, his son was already known as a leader of the Parliamentarian opposition, and a commander of their army. The youngest brother, Sidney, of Hinchingbrooke, was also a judge, serving as a Master of Requests, part of a lawcourt closely attached to the Crown through the Privy Council. He remained a loyalist, and like his brother Edward was arrested in 1642; and though he was released, he too died in 1644, leaving a son, Edward, who became 1st Earl of Sandwich—his story will be picked up again towards the very end of this post.

Of the senior line, of Boughton, there were two brothers: Edward, 2nd Baron Montagu, who sided with Parliament in the Civil War, and Sir William, another lawyer and a member of the House of Commons for fifty years. Charles II favoured the latter with the office of Chief Baron of the Exchequer (a judge), 1676, but he was removed by James II in 1686. We thus see this family continually balancing between military and judicial service, and between loyalty and opposition. The 2nd Baron’s heir, another Edward, reversed his father’s position and helped bring about the restoration of the monarchy in 1660; he was rewarded with the office of Master of the Horse for Queen Catherine of Braganza, but was killed in 1665 in the Anglo-Dutch War before he could succeed to his father’s title, which thus passed in 1684 to his brother Ralph, who had already taken over the post of the Queen’s Master of the Horse.

Ralph Montagu was a court gallant in the Restoration. He served as a diplomat in France in 1669-70 (when Charles II and Louis XIV were trying to form an unwieldy alliance), then was given a prominent court position, Master of the Great Wardrobe, 1671, but fell from favour for trying to bring down the Earl of Danby as first minister along with his chief supporter the Duchess of Cleveland, and for supporting the Exclusion Party in Parliament (the faction trying to exclude the Catholic James, Duke of York from succeeding to the Crown). Charles II thus removed Montagu from his court posts in 1678.

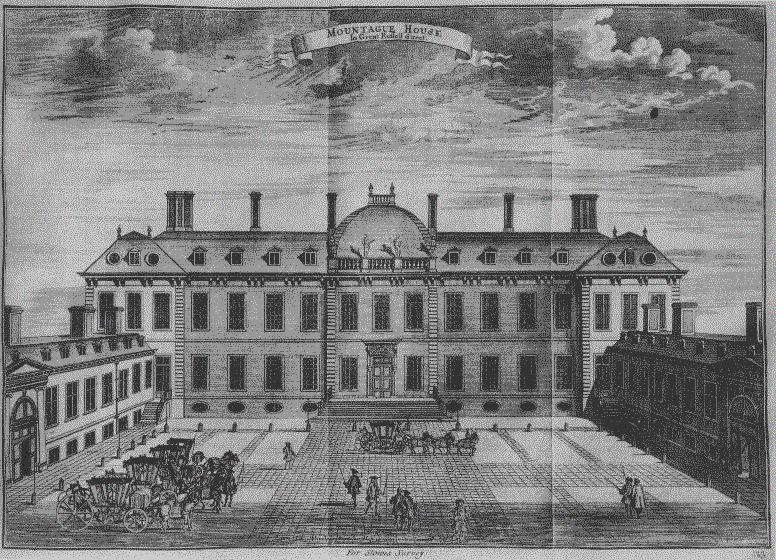

Succeeding to the peerage as 3rd Baron Montagu in 1684, he focused on rebuilding Boughton House as we’ve seen above, recalling the grand French châteaux he’d seen when he was ambassador. He also built a grand London mansion, Montagu House, situated on the northern edge of the old city, next to open fields in a district known as Bloomsbury. The house was built starting in 1675, with French and Dutch influences, and murals by renowned Italian painter Antonio Verrio, but in 1686 it burned down, and Montagu had to start again. The second Montagu House was grander and more clearly influenced by French classicism. In the 1750s, thinking the Bloomsbury area becoming too ‘middle class’, Montagu’s son sold the house to the newly founded British Museum. The site remains the home of this classic British institution, though Montagu House itself was torn down in the 1840s and rebuilt as a much more imposing Greek Revival building.

Ralph, Baron Montagu of Boughton, returned to royal favour after he backed William III in 1689, and was restored to his post as Master of the Great Wardrobe. He was also created Earl of Montagu and Viscount Monthermer—the latter title a formal recognition by the Crown that his family was indeed descended from the ancient House of Montagu. The Earl had married a very wealthy heiress, Elizabeth Wriothesley, heiress of the earls of Southampton, and potentially heiress of her first husband the Earl of Northumberland. She died in 1690, and two years later Montagu married again, another rich widow: Elizabeth Cavendish, heiress of her father the Duke of Newcastle and of her first husband, the Duke of Albemarle (Christopher Monck). It was said at the time that the Dowager Duchess of Albemarle was ‘mad’ (and some joked she was the ‘Monkey Duchess’ punning on her first husband’s surname) because she was convinced that, as the greatest heiress in England, she could only remarry a crowned head, and somehow thought this must be the Emperor of China. And so (as the story goes), Ralph Montagu dressed up in Chinese robes, proposed, and she accepted.

One of the properties Elizabeth Cavendish brought into the Montagu portfolio from Albemarle was the Lordship of Bowland, a vast wilderness of hills and dales in Lancashire. Its extent was enormous, covering about 800 km2 with ten manors and four parishes. It had been designated the ‘Forest and Liberty of Bowland’ by the Normans, and was held with the Honor of Clitheroe by the de Lacy family, then passed to the earls of Lancaster in the fourteenth century. It thus became part of the Duchy of Lancaster, which was held directly by the Crown, until the Restoration when Bowland was granted to General Monck as part of his new dukedom of Albemarle. Along with most of the Montagu of Boughton branch properties, the Lordship of Bowland passed to the dukes of Buccleuch at the start of the nineteenth century, and from them to the local Lancashire Towneley family. The title was disused by the end of the century, but was revived in 2008 when it was sold to a private (and secret) person at Cambridge University.

After such a long career, and now with a fantastic fortune, Ralph, Earl of Montagu, was promoted by Queen Anne in 1705 to Duke of Montagu and Marquess of Monthermer. This promotion was also thanks to the favour Montagu had with the Duke and Duchess of Marlborough, whose daughter Mary his son married that same year. The 1st Duke died a wealthy and powerful man in 1709. His Duchess—the ‘Empress of China’—survived for another twenty-five years in the halls of what is now the site of the British Museum. Maybe she haunts it still?

Their son John, 2nd Duke of Montagu, was active in both government and society. He was interested in science and medicine, as a founding governor of the Foundling Hospital in London in 1739, and a Grand Master of the first Masonic Lodge in England in 1725. He was named governor of the islands of St Lucia and St Vincent in the West Indies in 1722, but the British were soon chased off these islands. In 1740, Montagu’s political career was crowned with the office of Master-General of the Ordnance, a post responsible for organising military supplies, hospitals, transportation etc…and thus often one of the most lucrative positions in government, as each commission always came with a ‘fee’.

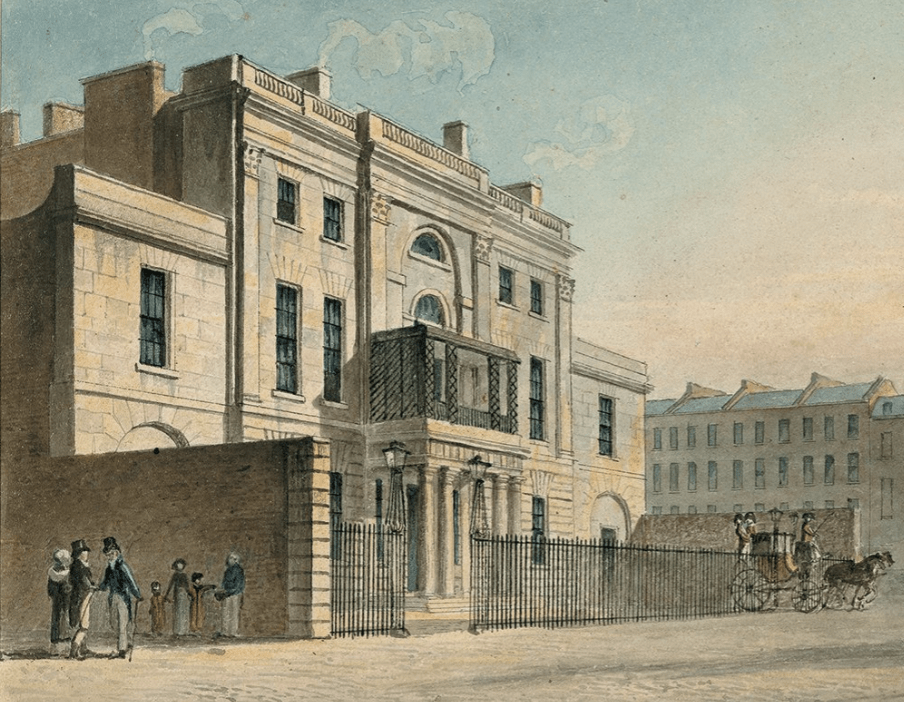

The 2nd Duke moved his chief London residence away from Bloomsbury in the 1730s and built another Montagu House in the more aristocratic district closer to Westminster on Whitehall Street. The site had been the location of the London residence of the medieval archbishops of York, and later part of the Whitehall Palace complex itself (before it mostly burned down in the 1690s). This second Montagu House was relatively modest, with a front on the Thames. Like Boughton, it passed to the dukes of Buccleuch in the nineteenth century, who replaced it with a much grander building. This was demolished in 1949 and the site is today part of the Ministry of Defence buildings.

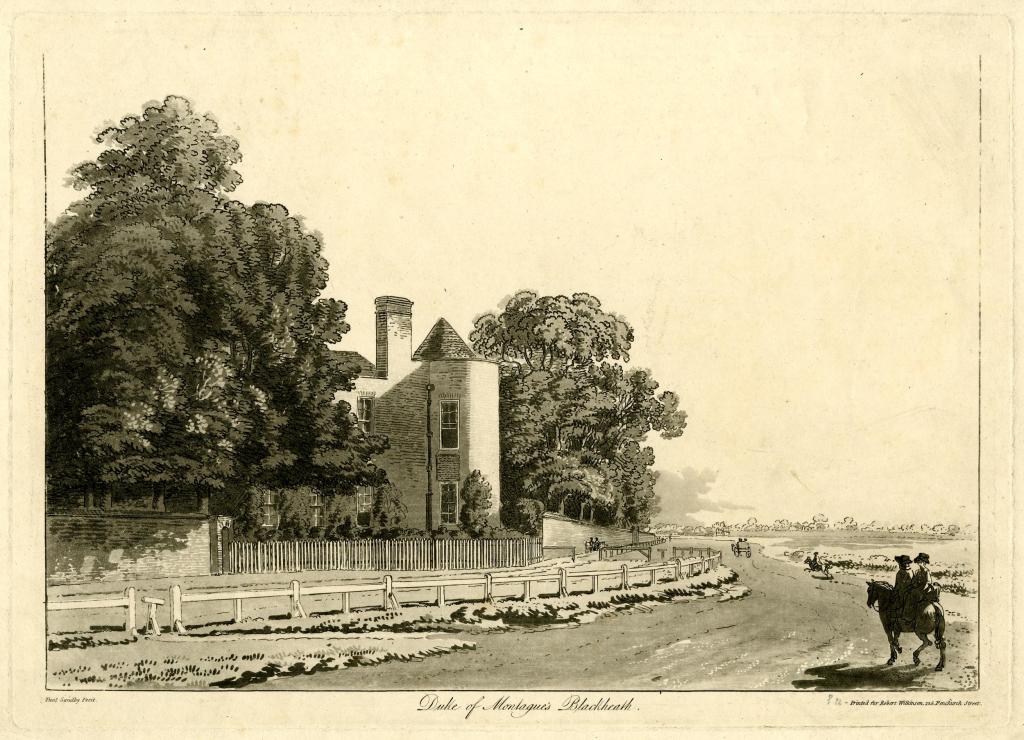

There was even a third Montagu House, built by the 1st Duke at Blackheath Common, overlooking Greenwich Park and the Thames valley in southeast London. Eighteenth-century Montagus used this house as a retreat from the smells of urban London, but it is best known for housing a royal tenant, Caroline of Brunswick, Princess of Wales, estranged from her husband and thus from court, who lived here with her daughter, Princess Charlotte, between 1799 and 1812. It was the scene of Caroline’s alleged love affairs and gained lots of bad press, so in 1815 it was torn down. All that remains today are tennis courts on the site.

John and Mary Montagu had a son, John, who died when he was five, and two daughters. The first, Lady Isabella, married the 2nd Duke of Manchester (below), then Edward Hussey, an MP from an old Anglo-Irish family, who legally took the name Hussey-Montagu, and when he retired from Parliament in 1762 was created Baron Beaulieu, of Beaulieu (Hampshire), then in 1784, advanced to Earl of Beaulieu. They had a son, John, Lord Montagu, another MP, but he died before his father, and when the latter died in 1802, these titles went extinct.

The younger daughter, Lady Mary, married George Brudenell, 4th Earl of Cardigan, who also took the name and arms of Montagu. The Brudenell family were, like the Montagus, a landowning family from Northamptonshire, based at Deene Park; and like the Montagus they also rose to prominence through the career of a sixteenth century high court judge. Made barons in 1628, then earls in 1661, they only renounced Catholicism in 1709. The 3rd Earl had married Lady Elizabeth Bruce, heiress of the Earl of Ailesbury and Elgin, so while the eldest son George was set up with the earldom of Cardigan, and later the Montagu succession, the younger son Thomas took the name Bruce and was re-created Earl of Ailesbury in 1776. This was a family on the rise, and the 4th Earl was swiftly named Justice in Eyre North of the Trent, 1742, Governor of Windsor Castle, 1752, and re-created Duke of Montagu in 1766. He was later given a seat on the Privy Council and finally named Master of the Horse, 1780. In London, the Brudenell-Montagus lived at Montagu House on Whitehall and at Cardigan House. In the countryside, they inhabited Boughton House or Deene Park, and further afield enjoyed the revenues of the Forest of Bowland, which the Duke inherited from his sister-in-law Isabella in 1786 (his Duchess, Mary, had died in 1775).

As with his first cousin John Hussey-Montagu, John Brudenell-Montagu was set up as a politician and an heir: in Parliament he was moved to the House of Lords as Baron Montagu of Boughton in 1762 (as a Tory supporter), then became Marquess of Monthermer as courtesy title when the dukedom was re-created for his father and mother. But he too died before his father; so in 1786, the Crown re-created the barony of Montagu once more, this time with special remainder for his father and then for his nephew. In 1767, his sister Lady Elizabeth had married Henry Scott, 3rd Duke of Buccleuch, a descendant of King Charles II, and their second son, Henry, took the name Montagu-Scott and 2nd Baron Montagu of Boughton on his grandfather’s death in 1790. He was also Lord of Bowland. He died in 1845 with only daughters, so the barony went extinct, while the Lordship of Bowland went to his older brother’s descendants, who now took the triple-barrelled surname Montagu-Douglas-Scott. This offshoot of the Montagus—who also inherited the house at Boughton and several other properties noted here—will have their own separate blog post as dukes of Buccleuch.

This is one of the more complicated arranging and re-arranging of surnames and titles that seems to have been commonplace amongst the British aristocracy of the eighteenth century. In the end, the headship of the house of Montagu passed to the next line, Manchester, while the junior line of the house of Brudenell reclaimed its earldom of Cardigan, and its seat, Deene Park, where they still live today, having merged with the earldom of Ailesbury (one of the Bruce titles), raised to a marquessate in 1821.

**

We pick up the Manchester line again with the 2nd Earl who succeeded his father at the start of the English Civil War. Edward Montagu had already been advanced to the House of Lords in 1626 as Viscount Mandeville (also known as Baron Kimbolton), and unlike his father was a vocal opponent of royal absolutism. As 2nd Earl from 1642, he became a Parliamentarian general, in command of the eastern counties in 1643, and leading the forces to victory at the Battle of Marston Moor. In subsequent years, Oliver Cromwell challenged his commitment to the cause and he resigned. The Earl of Manchester took up his seat in the House of Lords where he tried to reconcile the Parliamentarians with the Royalists, and tried to avoid bringing the King to trial. Having failed at these goals, he retired from public life during the Commonwealth, and was ultimately rewarded by Charles II in the Restoration with the post of one of the commissioners for the Great Seal of England and the Order of the Garter.

The seat of this branch of the Montagus was Kimbolton Castle in Huntingdonshire (today part of Cambridgeshire). A castle was built here in the twelfth century by the 1st Earl of Essex, Geoffrey FitzPeter, whose sons adopted the name Mandeville, after one of their maternal ancestors (Geoffrey de Mandeville had been one of the companions of William the Conqueror a century before), and this name will re-appear frequently in the history of the House of Montagu. In 1522, the medieval castle was acquired by Richard Wingfield, a Tudor courtier and diplomat, who rebuilt it as a Tudor manor house, with a moat. Because it was secure with a moat, and relatively far from London and the court, Kimbolton was offered by Wingfield as a residence for the disgraced Queen Katherine of Aragon (now recognised officially only as the Dowager Princess of Wales). Wingfield was a well-connected host, as a cousin of Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk (Henry VIII’s best friend and brother-in-law), and also a diplomat who had earned the favour of Emperor Charles V, Katherine’s nephew. She lived at Kimbolton in total isolation, seeing almost no one and only leaving her rooms to attend mass in the castle’s chapel, from May 1534 until her death in January 1536. The Wingfields organised her funeral at nearby Peterborough Cathedral. In 1615, Kimbolton Castle was purchased by the future 1st Earl of Manchester; it was then rebuilt by the 1st Duke of Manchester in about 1700, in a classical style but with battlements to give it more of a ‘castle’ feel. Over the next two centuries, most of the Manchester family would be buried in St Andrew’s church in the village, but the house itself slowly fell into disrepair, only to be overhauled, with indoor plumbing and electric lights, in the 1930s, but at far too much cost, forcing the sale first of the contents in 1949, then of the castle itself in 1950. It now houses the Kimbolton School, and is only open for tourists on certain open days each year.

The 2nd Earl of Manchester died in 1667, and although he married five times, he had only one son, Robert, the 3rd Earl, who did not live long as earl, and died in 1683, having served as a Gentleman of the Bedchamber for Charles II and Lord Lieutenant of Huntingdonshire. His son Charles would become the 1st Duke of Manchester, but before we move to him, the 2nd Earl’s younger brothers and nephews should be mentioned.

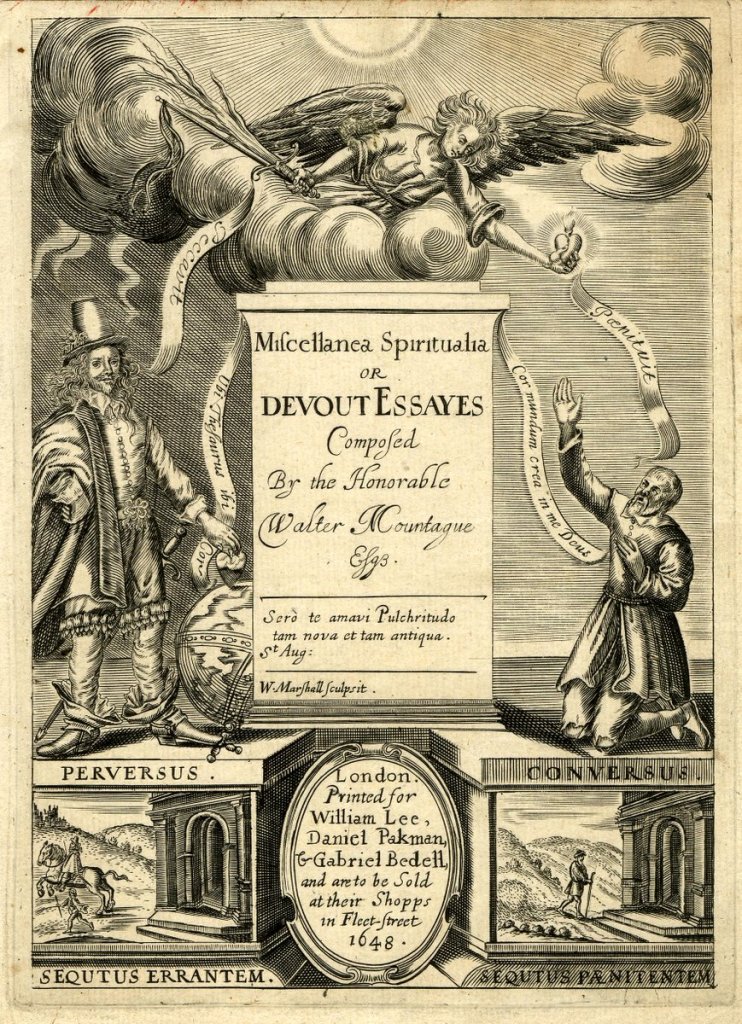

Walter Montagu is one of the most fascinating members of the family—and certainly for me as a historian of the court of Louis XIV. He was sent several times as a diplomat from Charles I to France in the 1620s-30s (often with secret instructions). In 1634, he converted to Catholicism and was given a place in the household of the French-born (and Catholic) Queen Henrietta Maria. In the Civil War Montagu left with the Queen for France, and joined a monastic community, becoming abbot of a Benedictine monastery in Nanteuil and also abbot of St-Martin of Pontoise (with its generous revenues) through the intercession of the Queen and her sister-in-law, the Regent of France, Anne of Austria (on whose behalf he continued to run secret missions to England in the 1640s). In 1647, Abbé Walter was named Chaplain to the British queen, and her almoner (her court at this point was based in the Palais Royal in Paris). During the Restoration Abbé Montagu lived at the Queen Mother’s court at Somerset House in London, then returned with her again to France in 1665, and officiated at her funeral at St-Denis in 1669. He then joined the household of Henrietta Maria’s daughter, Henriette, Duchess of Orléans, but she died the following year, so he retired from court and died in 1677.

A younger half-brother, George, of Horton Hall, was an MP for Huntingdonshire in the 1640s, then for Dover in the 1660s-70s. Horton Hall was also in Northamptonshire, but on the opposite side from other Montagu properties, close to the border with Buckinghamshire. It was an old estate owned in the sixteenth century by the Parr family (relatives of Queen Katherine Parr); Baron Parr of Horton built a Tudor mansion. Acquired by the 1st Earl of Manchester then held by this younger branch of the Montagu family—and rebuilt in the 1740s in a palladian style—it was later sold in the 1780s to diplomat Robert Gunning. Horton passed through other hands in the nineteenth century, then was demolished in 1936.

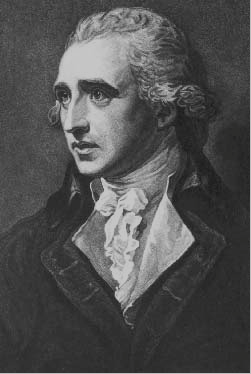

Hon. George Montagu of Horton had two sons: James was a judge and Whig politician, rising to the post of Attorney General in 1708 and Chief Baron of the Exchequer in 1722; Charles was also a Whig politician, but rose more prominently as part of the ‘Whig Junto’ who often ran the government in the reigns of William III and Anne. In 1694 he was Chancellor of the Exchequer, and one of the driving forces behind the creation of the Bank of England. King William created him Baron Halifax (of Halifax in Yorkshire). He later was a major supporter of the Act of Union (1707, joining England and Scotland), and of the Hanoverian Succession, so in 1714 was rewarded by George I with the post of First Lord of the Treasury and the earldom of Halifax. He died the following year, so the barony passed to his nephew George, who was re-created Earl of Halifax that same year. He was appointed Ranger of Bushy Park in west London and built the ‘Upper Lodge’ in 1714/15, which today is known as Bushy House (and was for a time the residence of King William IV and his wife Adelaide).

George, 2nd Earl of Halifax is known most for his role in developing trade with the North American colonies in his capacity as President of the Board of Trade from 1749—and in that same year founding a new city, Halifax, in the colony of Nova Scotia. There are also counties in Virginia and North Carolina named for him (in fact quite close to each other, on the border between the two states). As a leading Tory politician of the 1760s, he was Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, First Lord of the Admiralty, and a Secretary of State. Unlike others of his party, he was a supporter of the rights of the colonists and opposed to slavery. He returned to government in 1770 as Lord Privy Seal in the new administration of his nephew and protégé, Lord North, but died a year later, his titles extinct.

Charles Montagu, 4th Earl of Manchester from 1683, was a supporter of the accession of William and Mary in 1689, and fought under William in Ireland. He was appointed Ambassador to France, 1699-1701, and to Venice, 1707-08, then under George I was given a post in the Household as Lord of the Bedchamber and finally elevated to a dukedom in 1719. This meant there were now two Montagu dukedoms, Montagu and Manchester, a rare honour for a single family. He died three years later and the title passed to his heir, known as Viscount Mandeville.

William, 2nd Duke of Manchester, was, like many of his family, Lord Lieutenant of Huntingdonshire. He was also, like the Duke of Montagu, one of the founders of the Foundling Hospital in London. As we’ve seen, he married his cousin Lady Isabella Montagu, but they had no children, so when he died in 1739, the titles passed to his brother Robert.

The 3rd Duke of Manchester was a Whig politician (unlike his cousin the Earl of Halifax), and Lord of the Bedchamber for George II from 1739, then Lord Chamberlain for Queen Charlotte form 1761 until his death a year later. He had two sons: the younger, Lord Charles Montagu, was one of the last royal governors of South Carolina (off and on three times between 1766 and 1773), and commander of a regiment of redcoats in the War of American Independence. He did not make it back to Britain and died in 1784 in Nova Scotia, appropriately in Halifax, where he is buried.

George, 4th Duke of Manchester, took over from his father as Lord of the Bedchamber in 1762, and set about remodelling Kimbolton Castle and developing properties in central London. In the ministry of his cousin Lord North, he was appointed Lord Chamberlain of the Household, 1782, and a member of the Privy Council, but was removed when the North government fell a year later. Instead, he was sent as Ambassador to France (by now a familiar posting for his family) where he helped settle the details of the Treaty of Paris, 1783, that ended the war in North America.

The Manchester properties in London were part of the Portman estate in Marylebone, across Oxford Street from Mayfair. In the 1770s, the 4th Duke developed Manchester Square, and on one side built Manchester House. This name did not remain very long however: after a short stint as the Embassy of Spain in the 1790s, the house was sold to the 2nd Marquess of Hertford (of the Seymour family) in 1797. Again used as an embassy, this time for France (1836-51), the house, now called Hertford House, eventually passed—along with one of the greatest art collections of the age—to an illegitimate son of the 4th Marquess, Richard Wallace, who bequeathed it to the nation in 1890. The Wallace Collection in Hertford House still presides gracefully over Manchester Square.

William, 5th Duke of Manchester, succeeded his father in 1788. He had led a fairly quiet life as Lord Mandeville, but made an impact later on, notably as Governor of Jamaica, 1808 to 1827, during which time he oversaw the abolition of slavery in that colony. He had married a daughter and co-heiress of the Duke of Gordon, but she ran off with a footman in 1812 and they legally separated.

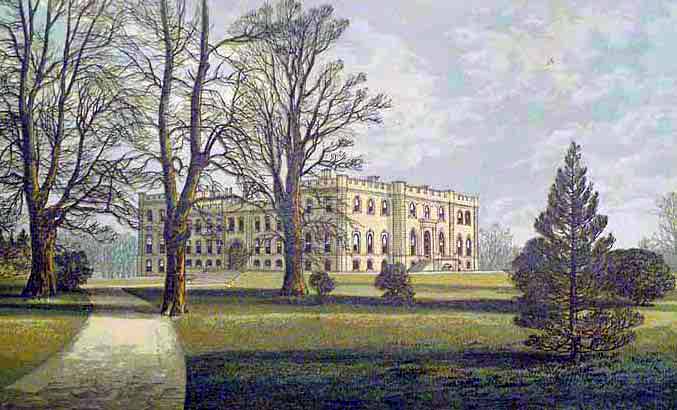

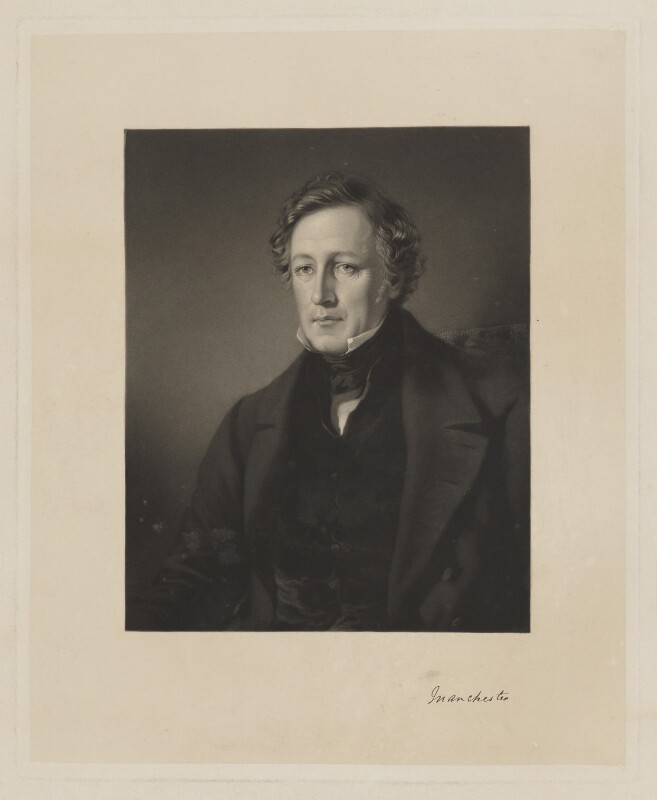

Their son, George, 6th Duke of Manchester, was known for most of his life as Viscount Mandeville (and gave this name to a parish in Jamaica while his father was governor) since he only held the ducal title from 1843 to 1855. At this time there was a neogothic revival in Britain, and a passion for all things medieval; the Montagus joined in the fun by reviving the name Drogo, which appeared somewhere in the list of names of sons in every generation from here on. The Duke also married an heiress, Millicent Bernard-Sparrow, daughter of a general and heiress of Brampton Park in Huntingdonshire, and large estates in Ireland.

Brampton Park had a red brick house from the sixteenth century, built by the Throckmortons. It was then owned by the Bernard family (baronets) and was rebuilt by the last heiress, Olivia Bernard, Lady Sparrow, a prominent philanthropist, in the 1820s. Much of the house was destroyed by fire in 1907; it was restored and lived in by the Manchester family in the 1920s-30s, then housed German prisoners of war in World War II. It became the officers’ mess building for the Royal Air Force at Brampton, 1955 to 2013, and is now being developed into residential units.

The heir to the Montagu and Bernard fortunes, William Drogo, 7th Duke, was thus a very wealthy landowner, with 13,000 acres in Huntingdonshire and 12,000 in County Armagh, Ireland. He was passionate about religion, and was active in the Canterbury Association, set up in 1848 to colonise New Zealand—he bought land there and was encouraged to emigrate and lead the new colony, but he didn’t—then from 1861 to 1888, he was Grand Prior of the Order of St John (the Protestant charity set up to replace the old Order of St John, aka Malta).

In 1852, the future duke married the intriguing German countess from Hanover, Luise von Alten, a courtier who became Mistress of the Robes to Queen Victoria, 1858-59, and a noted political hostess and friend of the Prime Minister, Lord Derby (whose grandson later married her daughter Lady Alice Montagu). Widowed in 1890, Duchess Louise soon married the Duke of Devonshire, gaining her nickname the ‘Double Duchess’. She was known as a great beauty and a member of the Prince of Wales Set (the friends of the future King Edward VII).

Her son, George, 8th Duke of Manchester, also made an interesting marriage, in 1876, to Consuelo Yznaga, daughter of a Cuban plantation owner and niece of a New York banker. She came with a six million dollar dowry, then inherited further millions from her brother in 1901; she was one of the inspirations for characters in Edith Wharton’s The Buccaneers—Wharton had known the Duchess personally, but the book didn’t come out until 1938, long after her death. Consuelo commissioned the famous Manchester Tiara from Cartier in 1903, which kept the family afloat even in its darkest moments, then was given to the nation in 2007 to cover death duties (now housed in the Victoria & Albert in London).

But such extraordinary wealth also seems to have brought on the downturn in fortunes of the House of Montagu, from which it is still reeling. Part of the problem was the collapse in the 1880s of the land rental market in Britain, resulting in a drop in income for the Manchester landed estates from £90,000 to £25,000. But the 8th Duke also made matters worse through poor financial decisions. As Viscount Mandeville, George Montagu had a modest career as an MP and soldier, but became better known as a drunk and a social outcast. He spent most of his wife’s dowry on gambling and women (notably a mistress, music-hall singer Bessie Bellwood), so was exiled by his father to Tandragee Castle in Armagh. His wife remained in London. The same year he succeeded to the dukedom, 1890, he was declared bankrupt, and died just two years later of cirrhosis, only 39. His widow lived on until 1909.

Tandragee was originally the seat of the O’Hanlon family. Confiscated after Ireland’s Nine Years War in 1603, the estate and its castle were given to the St John family, then destroyed in the rebellion of 1641 when the O’Hanlons tried to take it back. The Sparrow family acquired the estate in the eighteenth century and it thus passed by marriage to the dukes of Manchester. The 6th Duke rebuilt the castle, and it became the secondary residence of the family after Kimbolton. In 1956, his impoverished descendants sold it to a local man who installed a business he had created: the very glamourous sounding Tayto Potato Crisp Company.

The teenaged William (Lord Kimbolton while his grandfather was alive and known as ‘Kim’ by his friends for the rest of his life) became 9th Duke of Manchester in 1892. He was able to avoid some of the worst of his father’s bankruptcy by relying on his mother’s sizeable American estate, wisely kept separate. But like his predecessors, he spent a lot of money, entertaining, travelling, collecting, and gambling. As a young peer he joined the Liberals in Parliament and was appointed Captain of the Yeomen of the Guard in 1905 by the government of Campbell-Bannerman. Five years earlier, he had married another American, Helena Zimmerman of Cincinnati, another heiress as daughter of a railroad president and major stockholder in Standard Oil. The marriage was in secret since his mother did not approve of the match—was this New York money looking down on Ohio money?

Eugene Zimmerman paid off many of Kim’s debts, and bought the couple an estate in County Galway, Kylemore Castle, 1903—a grand former abbey, which they had to sell not long after. Still the Duke’s debts grew and grew and he spent much of his time abroad evading creditors. His wife divorced him in 1931, and he immediately married the West End actress Kathleen Dawes. Soon after he was convicted of making false financial statements to a pawnbroker and sentenced to nine months in Wormwood Scrubs Prison in west London (his brother, Lord Edward, also spent time here in 1935, then died mysteriously in a Mexican jungle). The 9th Duke of Manchester died in disgrace in 1947.

Alexander, Viscount Mandeville (known as ‘Mandy’), now became the 10th Duke of Manchester. He had started a career in the Royal Navy in the 1930s, then moved to British East Africa (now Kenya) in 1946 to farm a huge estate—10,000 acres, where he could live like a duke, with 14 houseboys and 20 gardeners—and try to undo generations of profligate spending. He had spent a lot on Kimbolton Castle in the 1930s, bringing in modern plumbing and electricity, but by the 1950s, he sold it, and Tandragee Castle as well; as his businesses continued to fail in the 1960s, he sold of the rest of the family’s interests in the United Kingdom. He was succeeded in 1977 by his elder son, Sidney (also known as ‘Kim’), who continued to develop the family interests in Kenya and South Africa but only held the ducal title for eight years before his own death in 1985.

The new 12th Duke of Manchester seems to have inherited his grandfather’s propensity for double dealing and evading the law. As a young man, Lord Angus Montagu (or ‘Aggi’) had moved to Australia where he worked as a salesman, a cattle wrangler, a barman and a crocodile wrestler. Much of his history is colourful and difficult to substantiate for certain, but he seems also to have worked in Texas oil fields and sold trousers in a Melbourne department store. By the 1980s Angus was living in a modest flat in Bedford, a short drive north of London, but also not too far from Kimbolton where he could maintain at least some family ties as ‘lord of the manor’. In 1985, on succeeding to his lofty titles (but inheriting next to nothing), he was charged with conspiracy to fraud a British bank, but was acquitted by a judge who deemed him too ‘absurdly stupid’ to be guilty, and duped instead by a cleverer con-man. Rather than retreat from this brush with the law, the new duke only increased his activities with associates often connected with the London criminal underground. And his debts continued to increase. Over the next decade he used his title to try to start up fundraising schemes, but was convicted of fraud in 1996 in the United States, where he spent two years in prison then was deported to the UK. He did set up a moderately successful tourism business in later years, offering Americans a chance to tour England in the company of a ‘real duke’. He married four times and died in his flat in Bedford in 2002.

Since 2002, the 13th Duke of Manchester has been Alexander Montagu, born in Australia in 1962, but living in the US since the 1980s. As a duke with no fortune he has also struggled to find his place, like his father spending time in prison (in Australia), and as recently as 2013 was charged with fraud for a bad cheque in Las Vegas, Nevada, and soon after that served time for burglary and making a false police report (for which he served several years in prison after 2017). But he has also been dogged by lawsuits and scandals involving his marriages. There are reports of a first brief marriage in Australia to a woman (who claims he tried to kill her), and legal protests from him that he does not owe child support for offspring from a marriage he says never existed. He had a second wife in the US for several years, whom he divorced, and although it seems he considers their son Alexander (b. 1993) to be his heir, it will be interesting to see how the British peerage regulators will consider him since (if the claims are correct) the Duke was still married to wife number one when he married wife number two. The heir himself, Viscount Mandeville, has himself already featured in the US press when he was a child as one of the many purported ‘special friends’ of Michael Jackson, then as an aristocrat working in fast-food in southern California to put himself through college. The online social media profiles of both the 13th Duke and his Duchess (a third wife, a real estate professional in Las Vegas) are a bit nutty, but I’ll leave this there, since I’m a historian, so will retreat to safer ground…!

**

Before wrapping up, there is one final line of the House of Montagu that reached prominence, and another earldom, that of Sandwich. Sir Sidney Montagu, youngest brother of the 1st Earl of Manchester, acquired another estate in Huntingdonshire: Hinchingbrooke. Like so many country houses in the history of the English aristocracy, this one began its life as a monastic building, a Benedictine nunnery from the eleventh century. It was secularised and acquired by none other than a nephew of Thomas Cromwell (the man conveniently behind the dissolution of the monasteries), in 1538. The Cromwells rebuilt it as an Elizabethan manor house in the 1560s, and held on to it until Sir Oliver (uncle of the more famous Oliver) got into financial difficulties and sold it in 1627 to Sidney Montagu. The Montagus of Hinchingbrooke were based here for the next three centuries, rebuilding the house after a major fire in 1830, then selling it in 1962 to Huntingdonshire County Council. In 1970 it became the main building of the Hinchingbrooke School.

Sidney of Hinchingbrooke’s son Edward was an MP in the 1640s-50s and a soldier in the Parliamentarian army. During the English Commonwealth he sat on the Council of State (1653-59) and was appointed General at Sea in 1656. He remained involved in naval affairs in the Restoration, benefitting from his familial link with naval administrator Samuel Pepys who was his mother’s great-nephew. The King created him Earl of Sandwich (in Kent) in May 1660 in recognition for his part in ensuring the Restoration earlier that year (with subsidiary titles Viscount Hinchingbrooke and Baron Montagu of St Neots, both in Huntingdonshire). He was entrusted with important diplomatic roles: Ambassador to Portugal, 1661-62 (to settle the King’s marriage with Catherine of Braganza), and Ambassador to Spain, 1666-68 (to negotiate the Treaty of Madrid, 1667, which aimed to block French advances in the Low Countries and to mediate between Spain and Portugal). Lord Sandwich continued his naval career and was killed at the Battle of Solebay in 1672—such was his reputation in England that he was given a state funeral.

As this branch were not dukes or princes, we shouldn’t follow its path entirely, but several names jump out as prominent members of eighteenth-century British society. John, 4th Earl of Sandwich, was a prominent politician and supporter of the expansion of Britain’s overseas empire. He was Secretary of State in the governments of George Grenville and Lord North in the 1660s-70s (the ‘Patriot Whigs’), and First Lord of the Admiralty off and on between the 1740s and 1780s; as such he sponsored the journeys of Captain Cook in the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, and had two distinct island chains named for him in the 1770s: the Sandwich Islands (aka the Kingdom of Hawai‘i) in the Pacific, and the South Sandwich Islands in the southern Atlantic (near Antarctica). There’s also Montague Island off the coast of Alaska and Hinchinbrook Island off the coast of Queensland, Australia. We remember him most, however, for being too busy at work on naval affairs to stop for lunch (or to stop at the gambling tables, depending on which tale you believe), so asking for meat to be placed between two slices of bread: a sandwich.

The earldom of Sandwich continues today with Luke Montagu (b. 1969), 12th Earl since February 2025. Since 1955 they have lived at Mapperton in Dorset, an ancient manor house rebuilt by the Morgan family in the Tudor era. Mapperton House has been voted one of England’s finest country houses, and its gardens regularly win heritage prizes—both are used frequently as sets for film and television.

Back in the eighteenth century, the younger son of the 1st Earl of Sandwich, Sidney, became very wealthy, having married his father’s ward, the heiress of the Wortley baronets of Wortley Hall, nearly Barnsley in Yorkshire. Under the ground at Wortley was black gold, coal, which Sidney developed with great financial success. His son Sir Edward Wortley Montagu was Ambassador to Constantinople, 1716-18, but it is his wife Lady Mary (daughter of the Duke of Kingston), who is more famous today, as a writer of letters and travel diaries, and in particular reporting on her experiences inside the Ottoman harem in Constantinople, where she learned of a technique for preventing smallpox, which she used on her own children and even convinced her friend back in London, Caroline, Princess of Wales, to use on the royal children. Her son Edward was also known as a traveller and a student of languages—going so far as to abandon English culture altogether and living ‘as a Turk’ in Venice in the 1750s-60s.

Another prominent member of the fashionable intellectual set of London society in this period was Elizabeth Montagu, wife of another Montagu cousin, who was known as one of the leaders of the ‘bluestockings’, educated women either admired or reviled for their learning and independence of spirit. This branch of the Montagus owned yet another ‘Montagu House’ in London, this one on Portman Square, in Marylebone—built about 1780, it survived until the area was bombed in the Second World War. There is also a Montagu Square nearby, developed in 1810 and named for the famous Salon hostess.

There is yet another peerage title ‘Baron Montagu’, this one of Beaulieu, created in 1885, famous for its beautiful Beaulieu Palace House in Hampshire (home to the National Motor Museum since 1952), and for the 3rd Baron’s imprisonment for homosexuality in 1954. But this branch more properly belongs to the Montagu-Douglas-Scott line, dukes of Buccleuch, so will be covered there.

One other claimed branch—distant, and of an unsure connection—is Montague of Boveney (in Buckinghamshire), which contributed one prominent churchman (Bishop of Chichester, 1628-38, then Norwich, 1638-41), and a colonist who migrated to Jamestown, Virginia in 1621. His family set up a plantation on the Charles River (now the York River), and left descendants, including Andrew Jackson Montague, the 44th Governor of Virginia, 1902-06.

From one of the richest and most powerful families in eighteenth-century Britain, the House of Montagu is today living under the shadow of the criminally indebted twentieth-century dukes of Manchester.

(images Wikimedia Commons)

Great stuff. I read, I cannot remember where, that Louise von Alten was an illegitimate daughter of the Duke of Cumberland. See you Tuesday. Best Philip

>

LikeLike