France and England share a tradition of using a select group of ducal titles for their second sons—most often York for England and Orléans for France. But not always, since, in both cases, if the holder of the second son title had his own son it carried on into the next generation, so the Crown would turn to another title for the second son, like Gloucester in England or Anjou in France.

The most famous dukes of Orléans are those younger brothers of Louis XIII and Louis XIV, Gaston and Philippe, the latter of which founded a dynasty that continues to the present day (the House of Bourbon-Orléans). But the title stretches back much further into the history of the French monarchy as a dukedom, and even further, to the very foundations of the monarchy, as a county and a kingdom.

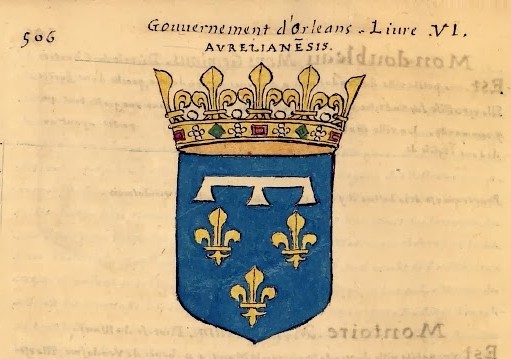

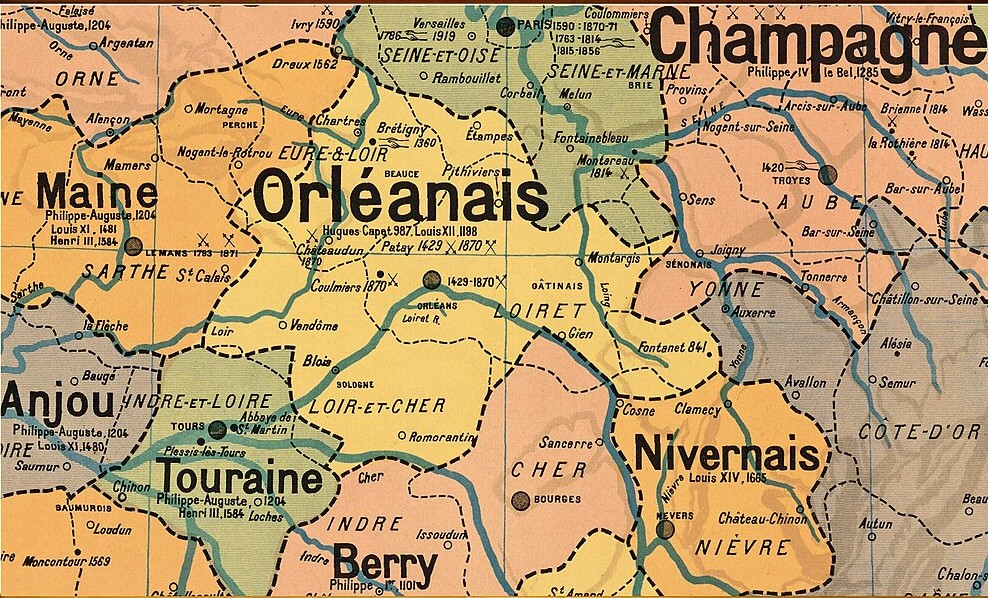

The Orléannais is one of the richest, most agriculturally productive regions of France, conveniently watered by the broad river Loire which also served as an efficient means to transport grains and grapes from France’s interior to its Atlantic ports. So it was a natural spot to base the centre of one of the early Frankish kingdoms under the Merovingians and Carolingians, and eventually became the prized possession and power base of the family that eventually unseated the Carolingians: the Capetians.

The city of Orléans itself is ancient, built at a good crossing spot on the Loire, so it developed into a trading centre for the people of Gaul, Cenabum, as far back as the second century BC. It was destroyed by Julius Caesar in 52 BC, then rebuilt several centuries later by the Emperor Aurelian (d. 275 AD), who renamed it after himself: Civitas Aurelianorum. By the Middle Ages it had become one of the three richest cities in France. Several important battles were fought here across the centuries, at this strategic crossing of the river: from Atilla the Hun versus the Franks and Visigoths in 451, to Joan of Arc versus the English a thousand years later in 1429.

The Merovingians and Carolingians divided and re-divided their Frankish kingdom into sub-kingdoms, including one based in Orléans, from the 510s until the reign of Charlemagne. Probably the most famous of these was Guntram, king of Orléans from 561-592, who ruled a fourth of the Kingdom, including much of the east (Burgundy). Two centuries later, Charlemagne reunited all of the various pieces of the Frankish realms, and granted the region of Orléans as a county to loyal Frankish generals. One of these, Odo (d. 834), was related to the royal family, and was a key support in their fight against the Viking invasions from the North Sea. Odo’s son Guillaume succeeded him as Count of Orléans, and his daughter Ermentrude became a queen, as wife of Charles the Bald, who later accused William of treason and executed him (866).

The County of Orléans was given to another Frankish lord, called Robert, founder of the Robertians who gathered a significant land power base in Orléans, Anjou, and Touraine (the old ‘March of Neustria’, a block of territory that protected the Frankish heartlands from Vikings and Gascons), and importantly the County of Paris and the area around it, which became known as the Duchy of France, or the Ile de France. This power allowed them to take the throne of France several times, and then more permanently under Robert’s descendant Hugh Capet, who had himself crowned in the Cathedral of Orléans in 987. Orléans remained the preferred seat of the Capetian monarchy well into the eleventh century.

But where did they reside? There’s little evidence of a royal palace in Orléans, but it was likely located on the riverbanks, next to what became known as the Châtelet—as in Paris, the name given to the seat of justice and its prison. Vestiges of the Châtelet of Orléans remain today. Like many cities in the Middle Ages, effective local power was exercised by the local bishop, who had a palace next to the Cathedral, while the counts and later dukes resided in the countryside in increasingly magnificent castles, for example Beaugency (see below). One significant early building in the city is the ‘King’s House’ (built in the early fifteenth century); constructed on the northeast edge of the old walled city, it was the administrative centre of the Orléannais, a law court, and housed princes or cardinals when they passed through the city. Rebuilt in the early sixteenth century as the Hôtel Brachet, then renamed the Hôtel de la Vieille Intendance in the eighteenth century, it has housed the tribunal court for Orléans since 1989.

Orléans and Paris became the two most important parts of the royal domain in the period when most of France was dominated by its feudal magnates. The first time the County of Orléans was given to a second son was in 1250, for Prince Philippe, son of King Louis IX. This was the era when French kings were creating the system of ‘apanage’: the lands and revenues could be enjoyed by a junior prince with a great deal of autonomy, but they remained ultimately part of the royal domain and would return to the pot if the apanagiste had no legitimate heir (they hadn’t yet learned that these should be males only titles, but they soon would, once Artois was lost through female inheritance…). Young Philippe (about fifteen) retained this title when his older brother Louis died in 1260 (there not yet being a tradition to name the heir ‘dauphin’), and went with his father on crusade to North Africa in 1270. The King died in Tunis, so Orléans became King Philip III (‘the Hardy’).

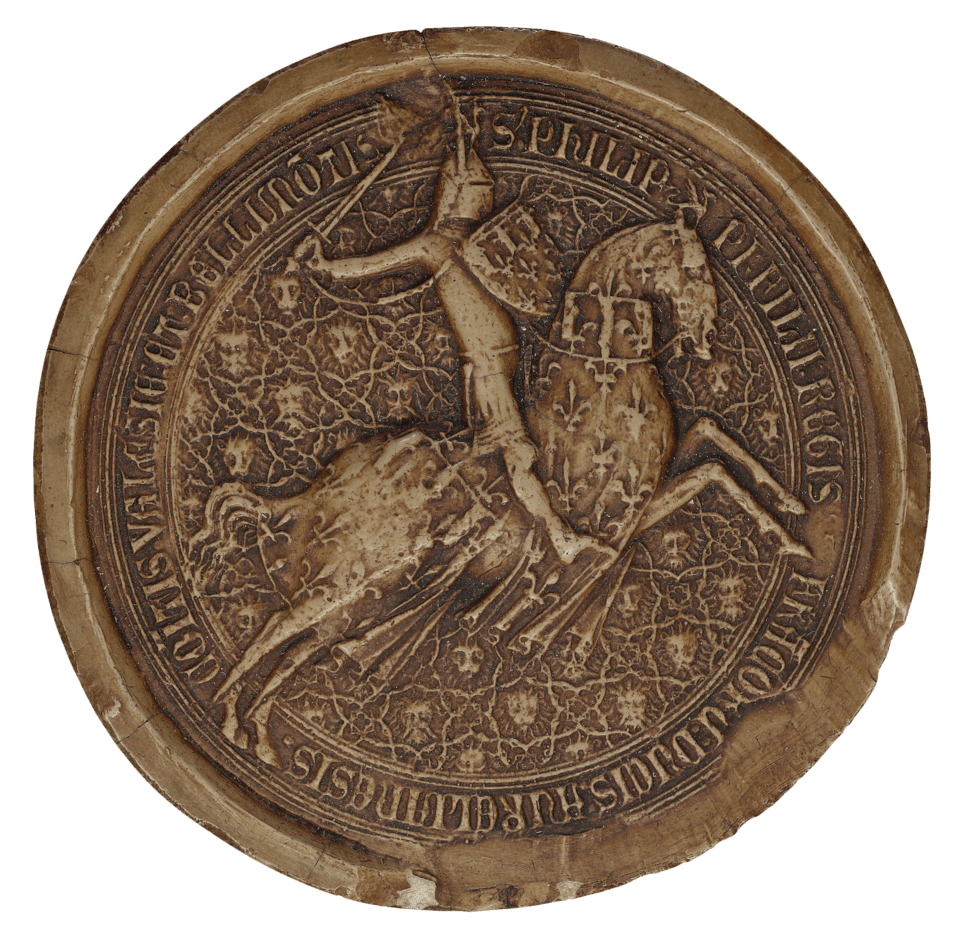

In 1344, Orléans was made a duchy-peerage and given to another Philippe, second son of King Philip VI, when he was about eight years old. He was also Count of Valois, another important part of the royal domain to the north of Paris, and Count of Touraine, immediately downriver from Orléans, which was also raised into a duchy-peerage. His father also married him (still age eight) to his cousin Princess Blanche of France, daughter of Charles IV. After Philip VI died in 1350, Philippe d’Orléans became an important supporter for his older brother, King John II. He fought alongside him at the Battle of Poitiers in 1356 (where John was taken prisoner), then was exchanged as a hostage of the peace forged by the Treaty of Bretigny, 1360—and remained in England until 1365.

One of Duke Philippe’s residences in his apanage was the Château de Beaugency, a few miles downriver from the city of Orléans. This was a stronghold built by the lords of Beaugency in the eleventh century, later acquired by the Crown in 1292, and given to Philippe in 1344. It is still one of the most impressive medieval castles in the Loire Valley, though much of what we see today was built slightly later by the Count of Dunois (below). His descendants, the Orléans-Longueville family, also made new additions, in the Renaissance style, in the 1520s, and it was held by subsequent dukes of Orléans until the French Revolution.

The 1st Duke had also acquired, at the start of King John’s reign, a grand residence in Paris from his brother, so he could also live like a prince in the Kingdom’s chief city. This was the Hôtel de Navarre, on the rue St-André des Arts (in the area between what’s now the Metro stops of St-Michel and Odéon). This princely residence had been built in the 1260s on the Left Bank (most other princes, notably the Duke of Burgundy, lived closer to the Louvre, on the Right Bank) by Thibaut, King of Navarre (held at that time by the French family of Blois-Champagne). When his descendant King Charles of Navarre clashed with King John of France, his estates, including the Hôtel de Navarre, were confiscated. This site would be the main Parisian residence for the dukes of Orléans until the era of Louis II in the 1480s, then was sold to various other proprietors until it was divided into two lots in the 1640s (and became the hôtels de Châteauvieux and Vieuville, entirely rebuilt in the eighteenth century).

The first Duke of Orléans died in 1375, at only 39 years old, leaving no legitimate children from his wife Blanche, though there were several illegitimate sons, including Louis d’Orléans, who became Bishop of Poitiers and Bishop of Beauvais, and died in 1397 on a trip to the Holy Land.

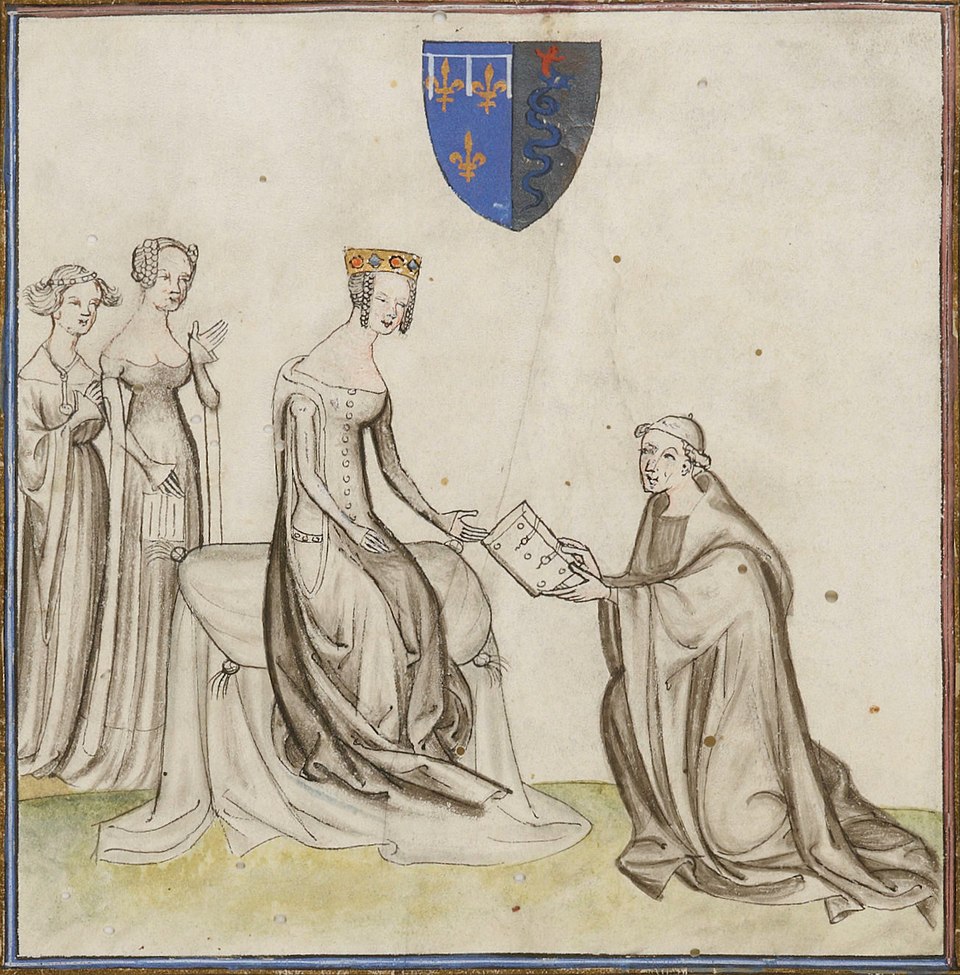

So the Duchy-Peerage of Orléans was re-created in 1392 for the first Duke’s great-nephew, Louis, the younger brother of King Charles VI. He had already been given lands from the royal domain, the Duchy of Touraine, in 1386, which he now exchanged for Orléans as well as the County of Valois (which was later raised to a duchy as well, 1406). Louis continued to acquire even more feudal estates, like the County of Château-Thierry and other lands in Champagne (the only other region of France equal to the Orléannais in the richness of its agriculture), the counties of Blois and Dunois (to add to his block of Orléans and Touraine), and the counties of Angoulême and Périgord, stretching his influence down towards the southwest of France—and spaces contested by the King of England.

In 1389, Louis married Valentina Visconti, the daughter of the Duke of Milan. She brought with her as a dowry the County of Asti, a small territory but strategically wedged between Piedmont, Lombardy and Genoa. She also ultimately became heiress to the Duchy of Milan itself—a factor that affected the histories of both France and Italy for a century—but not until the 1440s, well after her death.

Louis and Valentina became known as organisers of grand fêtes. In Paris they lived at the Hôtel de Navarre (or Hôtel d’Orléans), noted above. He was also given a smaller residence, the Hôtel du Petit-Musc, purchased for him by his brother in 1378, just inside the Paris city walls near the Porte Saint-Antoine (today’s Place de la Bastille). This building named for the street or district ‘Petit-Musc’ could refer to a small hidden street, or it may have been ‘pute et muse’, a hidden place to promenade with prostitutes. Nothing of it remains today as it was entirely rebuilt as the Hôtel de Boisy by the dukes of Roannais in the 1560s, then acquired by the Duc de Mayenne in 1605. A member of the House of Lorraine-Guise, Mayenne enlarged it into how we see it today, and it bears his name, so is part of the story of the dukes of Guise.

Outside Paris, Louis I preferred to reside not in his Duchy of Orléans, in a château like Beaugency, but his County of Valois, northeast of Paris in a region favoured by French royals for its excellent hunting grounds in the large royal forests of Compiègne and Villers-Cotterêts. The Duke rebuilt an ancient castle here, Pierrefonds, built by local nobles and acquired by the royal domain in the late twelfth century. Duke Louis rebuilt it completely in the 1390s, a massive structure with seven grand towers. Pierrefonds was later given to various nobles in the sixteenth century, then was dismantled on orders of Louis XIII in 1617—its ruins became a fashionable Romantic tourist spot in the nineteenth century, then the castle was almost entirely rebuilt on the orders of Napoleon III in the 1860s (in what is known as ‘Troubadour Style’, a sort of Romanticised vision of Medieval architecture), which is how we see it today.

Not far away was the Château of La Ferté-Milon, also a much older castle, acquired by the Crown for the County of Valois in the 1290s, and now added in the 1390s to the Orléans apanage. Louis also planned to rebuild this into a more elaborate residence, but it was still incomplete at the time of his death, and his successors took little interest in it. La Ferté-Milon was dismantled in 1594 on the orders of Henry IV, and remains a ruin.

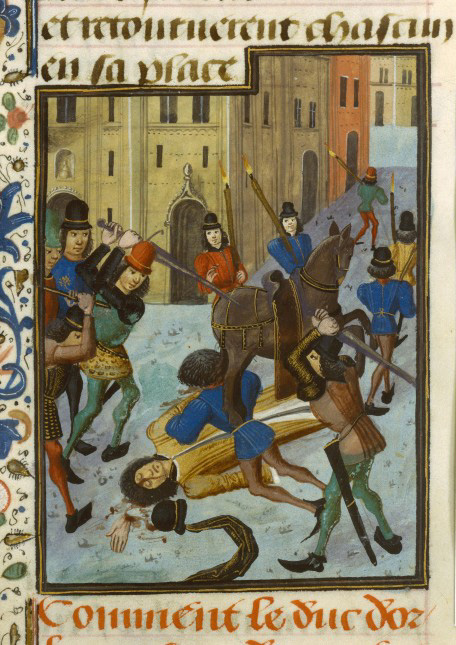

The Duke of Orléans was thus a very powerful magnate, with bases in the Loire valley, the Valois and in Paris, and able to step in when his brother needed him in 1392 when he was attacked by debilitating mental illness. The royal brothers’ uncle, Philippe, Duke of Burgundy, had been Regent of France while Charles VI was a child (1380-88), and he now re-asserted his power, pushing out the Duke of Orléans from any attempt to be regent for his unwell older brother. This starts a long and bloody feud between the houses of Burgundy and Orléans that continued for the next two generations. As part of this rivalry, in 1402, Orléans made yet another acquisition, the Duchy of Luxembourg, to spite uncle Burgundy’s desire to unite the northern and southern halves of his domain (but also perhaps to connect to his domains in Valois, on the road from Paris to Luxembourg). Philippe of Burgundy died in 1404, and was succeeded by his son Jean who continued to wield his father’s control over the King and his council. In frustration, the Queen, Isabeau of Bavaria, made an alliance with the Duke of Orléans and the Duke of Berry (another of the King’s uncles), December 1405, and by 1407 managed to push Burgundy and his supporters out of government and out of Paris. In response, Duke Jean got his men to assassinate the Duke of Orléans in the street near the Hôtel de St-Pol (the favoured royal residence, on the eastern edges of the city of Paris), in November 1407.

This murder provoked a civil war in France, Burgundians versus Armagnacs, so called for the new Duke of Orléans’s father-in-law, mentor and war commander, Bernard VII, Count of Armagnac. The new Duke, only 13, was named Charles. His marriage to Bonne d’Armagnac in 1410, at age 16, was in fact his second marriage, having married at first when he was 12 Isabelle of France, daughter of Charles VI (herself already the widow of King Richard II of England), in 1406. She died in childbirth in 1409, only 19 years old. The 2nd Duke of Orléans (of the second creation) made a bold debut on the battlefield at Agincourt in 1415, where miraculously he was not killed or maimed, but was captured and taken to England—where he remained for the next 24 years.

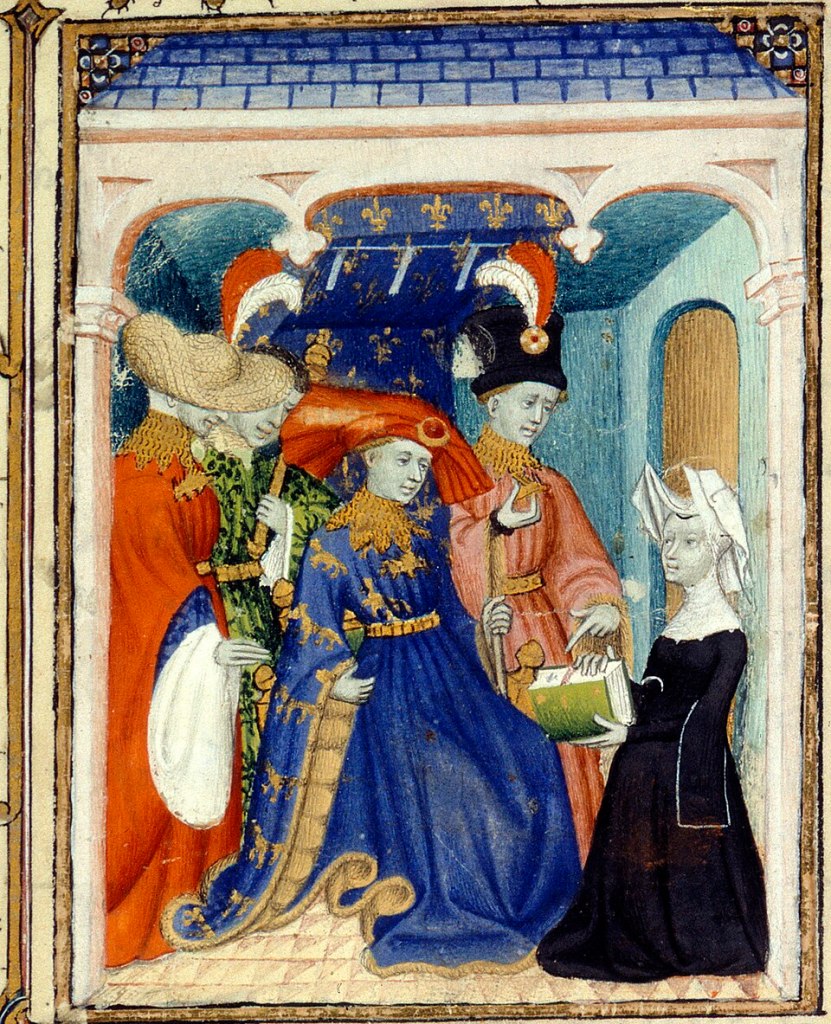

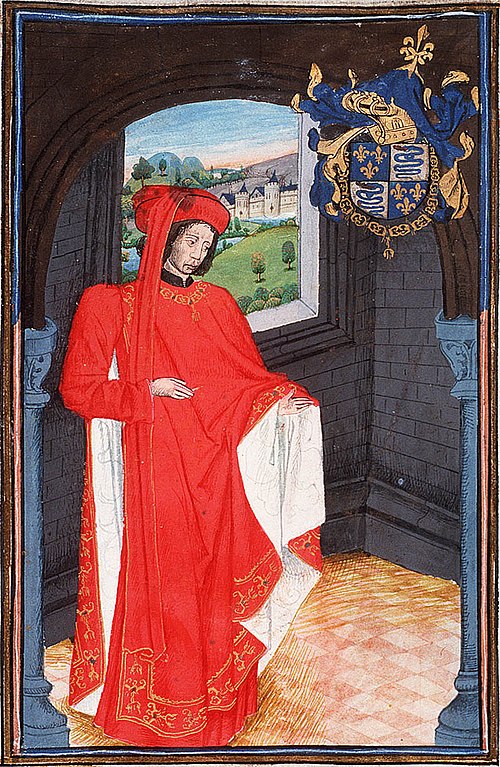

The Duke of Orléans, as hostage of the King of England, moved around a lot: the Tower of London, Bolingbroke Castle, Pontefract and others. Henry V refused to allow him to be ransomed, but the French prince was relatively free in his daily life, and spent this time becoming a poet—in fact, he is regarded as one of the leading poets of this period, in both French and English. Over five hundred of his poems survive, some of which were set to music in the late nineteenth century during a revival of all things medieval—notably the ‘Trois Chansons de Charles d’Orléans’, premiered by Debussy in 1909.

Orléans was finally freed in 1440 thanks to the intervention of the Duke of Burgundy (and lots of ransom money). In return, he had to promise to stop the vendetta seeking vengeance for his father’s murder. He solidified this new bond with a third marriage, now to Burgundy’s niece, Marie de Clèves, daughter of Adolf, Duke of Cleves (and it was her dowry that secured the ransom). He settled into his château at Blois where he nurtured a court of art and music and poetry. He died in 1465.

The 3rd Duke of Orléans, Louis II, was born from this third marriage, so was only three when he succeeded to his elderly father’s titles. But before we look at this generation, we need to look at Duke Charles’s brothers, Vertus and Angoulême, and his half-brother, one of the most famous men of this period, Dunois.

Philippe, second son of the 1st Duke of Orléans, was known as the Count of Vertus. This county in central Champagne had in fact been given as a dowry to a French princess who married into the ducal family of Milan, then returned with Valentina of Milan as part of her dowry. Both he and his older brother Charles quartered Orléans and Visconti in their coat-of-arms. Vertus took over as head of the Armagnacs while his older brother was held hostage in England, and supported the Dauphin Charles in his campaigns to recover his claims to the Kingdom after he had been disinherited by the Treaty of Troyes (between Henry V and Charles VI) in May 1420; but he died unmarried only a few months later.

Jean, the third son, was given the County of Angoulême as his part of the Orléans succession in 1407. He was sent to England as a hostage even before the Battle of Agincourt, in 1412, in an attempt to broker a peace. He was only 13. Like his oldest brother, he stayed in England for a very long time—33 years! Also like Charles, he was bookish, and when he returned to France finally in 1444, he brought back quite a library, some of which is still at the core of the National Library of France today. His son Charles, Count of Angoulême, did not make much of a mark himself, but was the progenitor of the House of Valois-Angoulême, fully royal once his son François succeeded to the French throne in 1515. But that’s a different story. Angoulême also joined the Dauphin’s campaigns versus the English in the 1440s, notably alongside his illegitimate half-brother Dunois.

Jean, ‘Bastard of Orléans’, is famous as one of the companions and generals of Jeanne d’Arc at the siege of Orléans, 1429, after which he helped the Dauphin, now calling himself Charles VII, drive the English out of France. In thanks, his brother (still in England) gave him the County of Dunois (west of Orléans, centred on the town and castle of Châteaudun, or ‘Château Dun’). The King augmented this with the County of Longueville in Normandy, by which title his descendants (who continued to use the surname ‘d’Orléans’) are known—they were raised to the rank of dukes in 1505, so will have a post of their own. Their coat-of-arms is a fascinating example of the intersection of cadency and bastardy: Dunois bore a three-point silver label of the House of Orléans ‘bruised’ by a silver bend sinister denoting bastardy. This bend was then reversed to become a bend dexter once the Orléans-Longueville family obtained legitimation as princes of the blood by the King of France in the sixteenth century—though their exact status as princes of the blood remained contested, much to their chagrin.

Inheriting the Orléans apanage at such a young age, Louis, 3rd Duke of Orléans was raised under the watchful eye of his mother, Marie de Clèves, and through her, the Duke of Burgundy. This new alliance—a complete reversal of family politics at the start of the century—worried the new King of France, Louis XI, who is remembered as one of the most politically manipulative kings in French history. As such, in a juicy anecdote that is often told, worthy of ‘Game of Thrones’, the King is said to have forced his young cousin Orléans in 1476 (when he was 14) to accept the honour of marriage to a royal princess, his own daughter Jeanne, despite knowing that she suffered from disfigurement that would prevent her from having children. A perfect way to kill off a rival dynasty. Specialists of the era now cast doubts on this story, pointing out that it was circulated during Orléans’ later proceedings to get this marriage annulled for political reasons, and that the ‘evidence’ he presented to the ecclesiastical courts also included accusations of witchcraft, so the story may have simply been part of the campaign concocted to blacken the reputation of Jeanne and her father. The marriage was indeed annulled, but in the long run, Jeanne won a rather large victory (in terms of the celestial and the eternal) as she was canonised as a saint in 1950.

As he matured, Louis of Orléans became known as a reformer, displayed at the Estates General of 1484, held in the city of Tours, where he supported demands for an end to corrupt taxation practices and to foreign influence in the French church and military. He also put himself forward as the best man to lead the Kingdom as regent, since Louis XI had died and his son Charles VIII was only 13 and temporarily being governed by his older sister, Anne, Dame de Beaujeu. The Estates General sided with Anne, and Louis and his reform ideas were pushed aside. The next year, Orléans joined a revolt against Anne’s regency, known as ‘the Mad War’ (la Guerre Folle), in league with the Duke of Brittany and other disgruntled grandees. He was defeated at captured at St-Aubin du Cormier, in eastern Brittany, in July 1488.

Pardoned in 1491, Orléans patched things up with his now adult cousin Charles VIII by going on campaign with him to Italy in 1494. The King was invited to the Italian peninsula by the Pope, to stake a claim on the Kingdom of Naples (to keep it out of the hands of the King of Aragon), but also by the Duke of Milan, who sought protection from his enemies in Venice and Florence—unwittingly reviving the Duke of Orléans’ claims to that Duchy himself in the name of his grandmother Valentina Visconti.

Suddenly, Charles VIII died, in April 1498. Though he and his wife, Anne of Brittany, had had several children, none of them survived, and there was no one else in line of succession, so Louis, Duke of Orléans, became Louis XII, King of France. Right away he marched back to Italy and finally took the Duchy of Milan in the Autumn of 1499. A year before, he had successfully arranged for his first marriage to Jeanne de France to be annulled, and he married the late King’s widow, Anne of Brittany, ensuring that Brittany remained a part of France. Domestically, Louis XII also put into place many of the reforms he had tried to champion at the Estates General back in 1484. The last Duke of Orléans of this line had a good reign as Louis XII, but is overshadowed in popular memory by his cousin and successor, Francis I. Lovers of Tudor history remember Louis XII as the elderly king who married Henry VIII’s sister Mary, and died shortly after from an excess of marital passion…

One of the chief castles Louis II of Orléans had inherited in his apanage was the Château of Blois. Not in the Orléannais, it was in the county next door, and had been built in the tenth century by the powerful Counts of Blois—one of the major feudal dynasties of the Middle Ages in France. It had been given to Louis I, first Duke of Orléans, when his apanage was created in 1392, and was inhabited in the 1440s by Duke Charles, the poet-duke, who made it a court of poets and musicians. But it wasn’t until Louis II became King that he began major renovation works and created the ‘Louis XII Wing’ of the château as we see it today, in flamboyant gothic style. The more famous wing at Blois is that built by Louis XII’s successor, Francis I, in a dramatic Renaissance style (with its famous twisting staircase). It remained a royal, not ducal residence, a favoured nursery for royal children, first for Queen Claude then for Queen Catherine de Medici, until it was given again as part of the Orléans apanage to Louis XIII’s brother Gaston (see below), who built a third magnificent wing in the 1630s, and had plans to demolish the other two wings and rebuild if and when (he assumed) he became king. The birth of Louis XIV in 1638 scuppered those plans (thank goodness!), then the French Revolution interrupted other plans to demolish the château in 1788 (!), so Blois remains mostly untouched, one of the finest heritage sites in the Loire Valley.

**

The reign of Francis I, starting in 1515, is usually seen as the turning point between the Late Medieval and Renaissance eras of French history. A few years later, in 1519, Francis and his queen, Claude (the daughter of Louis XII and Anne of Brittany), celebrated the birth of a second son, Henri, who was—as was now tradition—created Duke of Orléans. The young Duke, only 7, was sent to Spain as a hostage in 1526, along with his brother the Dauphin, in exchange for their father’s freedom following the shocking Battle of Pavia. Henri was said to be sulky and often melancholic after his return to France in 1530, hardly cheered by his marriage three years later to Catherine de Medici, a strategic marriage since she was niece of Pope Leo X (and also heiress of a significant chunk of central France) but not someone of rank deemed sufficient to marry a royal prince of the House of Valois. This discrepancy in rank became even more awkward in 1536, when the Dauphin François died, and Henri became the new Dauphin. The Orléans apanage was transferred to the next brother, Charles, three years younger.

Prince Charles had first been called Duke of Angoulême, inheriting this apanage on the death of his grandmother, Louise de Savoie, in 1531. After he became Duke of Orléans in 1536, his father continued to build up his estates, granting him the counties of La Marche and Clermont in 1540, as well as the Duchy of Châtellerault (in Poitou, a less prestigious title, but it came with a peerage, which gave Charles a seat in the Parlement of Paris). He was very much his father’s favoured son, and a court favourite, some say because of his more sunny disposition, having not suffered the three years of imprisonment in Spain as the Dauphin Henri did. The court even divided into rival factions in the early 1540s, presided over by the King’s mistress, the Duchesse d’Etampes (with Orléans) and the Dauphin’s mistress, Diane de Poitiers. This was exacerbated when the Duke of Orléans was successful in his early military career in 1542 while the Dauphin was not, and even more so when the King opened negotiations in September 1544 to secure a peace treaty with Emperor Charles V by means of a marriage between Orléans and a Habsburg (further highlighting the Dauphin’s low-born wife). The Emperor even offered as a dowry the Duchy of Milan, which the Dauphin thought should be his by right of his senior descent from Valentina Visconti. The King counter-offered by giving Orléans yet another duchy, Bourbon, a rich territory in the centre of France recently confiscated from the junior branch of the royal house. Negotiations dragged out until the Emperor finally agreed in September 1545, only to discover that the Duke of Orléans had died a few days before, of plague while on campaign near Boulogne. He was only 23.

The Dauphin Henri became Henri II in 1547, and despite their rocky start, he and Catherine de Medici had numerous sons. As before, the eldest, François, was named Dauphin, while the second son, Louis, was created Duke of Orléans (1549). He died only a year later (not yet two years old), and the apanage was transferred to the third son, another Charles. After the brief reign of Francis II, Charles became king as Charles IX in 1560, so the Duchy of Orléans was given to the next brother, Henri, who later exchanged it (in 1566) for the Duchy of Anjou.

The Orléans estates were given to their mother, Catherine, to add to her own estates, which included the Château of Chenonceau—famous for its long gallery extending across the river Cher—in the Duchy of Touraine. She had big plans to expand this royal residence, but the Wars of Religion caused delays, until her death in 1589 brought all these properties back into control of the Crown.

The next creation of the Duchy of Orléans as a royal apanage was in 1626, for Gaston de France, younger brother of Louis XIII. There had been a brief ‘Duc d’Orléans’ as a courtesy title (not a formal investiture as an apanage) for an unnamed second son of King Henry IV (lived 1607-1611, and sometimes erroneously assumed by genealogists to be named ‘Nicolas’, from the N. (‘not named’) printed in royal genealogies of the time), so Gaston (b. 1608) had been given the title Duc d’Anjou as a baby. His apanage of Orléans was given in 1626 as part of a marriage and peace deal after brief revolt against his brother (though he was only 18, so was mostly being manipulated by powerful courtiers). This marriage was to Marie de Bourbon-Montpensier, an incredibly wealthy heiress (owning huge chunks of central France). His apanage also included the duchies of Chartres and Valois and the County of Blois.

It was at Blois that Gaston, Duke of Orléans, focused much of his energies as a princely patron. He spent many years residing here in the 1630s-50s, as he had made himself very unwelcome at the court of Louis XIII. For years he remained, awkwardly, in the position as heir to the throne, from 1611 until his sister-in-law Queen Anne finally produced a male heir (Louis XIV) in 1638. He tried to be loyal, but continually got dragged into court intrigues and rebellion, which mostly ended badly…for his friends, since he himself could not be severely punished since he was, as ever, the heir to the throne. The Conspiracy of Chalais of 1626, the Day of Dupes of 1630, the Montmorency rebellion of 1632… Retiring to Blois from 1634, the Duke of Orléans hosted a number of artists, musicians and political exiles—men and women who had fallen foul of the King and his first minister, Cardinal Richelieu. Gaston had grand plans to expand this into a very grand royal residence, as we’ve seen above.

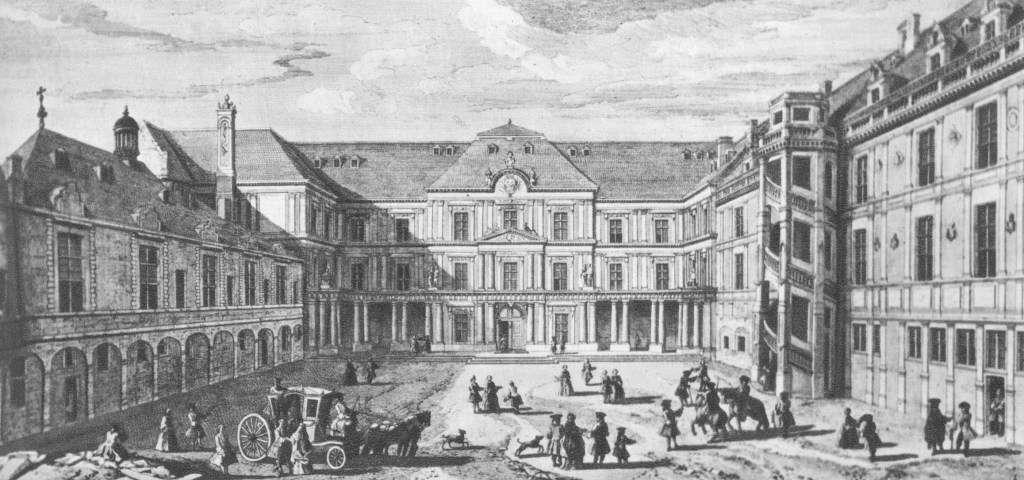

Gaston also had plans to build a much grander château at Chambord, located within the Duchy of Orléans itself. Chambord was at the centre of one of the largest royal hunting parks in France (which, incidentally, it still is), a part of the Orléans apanage since the 1390s, returned to the Crown in 1498, and favoured by Francis I, who built an entirely new château here in the 1520s. It was rarely used after the 1550s, so was due for renovation when Gaston set his eyes on it in the early 1640s. Chambord was held by the royal family once more after Gaston’s death in 1660, and was given as residence to various people in the next century—notably Louis XV’s father-in-law, the exiled King Stanislas of Poland—and remained property of the Bourbons even after the Revolution, finally being sold to the nation in 1930. In Paris, Gaston lived in his mother Marie de Medici’s grand new palace, the Palais du Luxembourg, which was called at this time the Palais d’Orléans.

Though he had two wives, Gaston died without a male heir. Marie de Montpensier had died soon after giving birth to a daughter, Anne-Marie-Louise d’Orléans, Duchess of Montpensier, better known to history as ‘La Grande Mademoiselle’. She and her father had a fraught relationship—he cherished her (and her money, as sole heir of her mother), but also very much wanted a son, to whom he could pass on the Orléans apanage. His second marriage, to Marguerite de Lorraine, sister of Charles IV, Duke of Lorraine and Bar, had been blocked by his brother the King, so he was not allowed to live with her until after his brother’s death in 1643. The Duke and Duchess of Lorraine once again made their home at Blois and started a family. A son, Jean-Gaston, was born in 1650, given the title Duke of Valois, but died only two years later. So Gaston and Marguerite focused on raising their three daughters, Marguerite-Louise, Elisabeth, and Françoise. These could not inherit the throne however, so when Gaston died in February 1660, the Orléans apanage returned once more to the Crown, and was given out again in 1661, to Philippe de France, younger brother of Louis XIV. Philippe d’Orléans is the founder of the House of Orléans that persists today.

To be continued in Part II

(images Wikimedia Commons)

One thought on “The Dukes of Orléans: A ‘Spare’ Title for France’s Second Sons (Part I)”