One of the most interesting aspects of the high aristocracy in European history is its fluidity. In the centuries before the rise of nationalism, elites could and often did move from place to place and adapt to new scenarios with relative ease. On this site, we’ve seen examples of this already with the Scottish Hamiltons in France, the Portuguese Lancastres in Castile, or the Livonian Lievens in Sweden. And the older you get with an aristocratic family, often the more mobility you get. One family whose claimed roots stretch back to the eleventh century were the Cantacuzinos, who began their journey amongst the military aristocracy of the Byzantine Empire, then re-emerged as Greek Phanariot merchant-princes under Ottoman rule in the mid-sixteenth century, and by the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries were regularly serving as Ottoman governors of the provinces of Wallachia and Moldavia—and later were prominent in the push towards fusing these provinces into the modern nation of Romania in the nineteenth century. Along the way, they also established separate branches of Russian princes, Austrian counts and French exiles. The spelling varies between Greek Kantakouzenos and Cantacuzino in Romanian to Cantacouzène in French.

The link between the Byzantine family who held several of the top posts in the imperial government from the twelfth to fifteenth centuries, and even briefly held the imperial title itself (John VI and Matthew, 1341 to 1357), and the family of Greco-Romanian princes in the sixteenth to twentieth centuries, is tenuous. Some historians dismiss it outright as a wild claim built on the chaos that followed the destruction of the Byzantine Empire in 1453; while others consider it plausible if unprovable. For the sake of this post, I am going to assume it is true, and although I will introduce the Byzantine family, I will move swiftly on to the more modern period, since that’s what I know more about as a historian.

The family first emerged amongst the military elites of the Empire of the East in the eleventh century: an early member was Manuel Kantakouzenos, a military commander in 1079. Speculation on the origin of the name has posited the joining of two Greek names Katina and Kusin, perhaps through a marriage, to form Καντακουζηνός (Latinised by medieval historians in the West as Cantacuzenus). Another thought is that they came from Kouzenas near Smyrna in Asia Minor. The real founder of the imperial dynasty was Ioannes Kantakouzenos, a military commander in the western parts of the Empire in the 1150s who rose to the rank of Pansebastos sebastos—basically ‘commander of all commanders’ (equivalent to the title ‘augustus’ in the West, second only to the emperor). He was killed in Anatolia, in battle against the Seljuk Turks in 1176, but not before siring at least one son with Maria Komnene, a relative of the ruling Komnenos (Comnenus) dynasty. His son Manuel was imprisoned and blinded by Emperor Manuel I Komnenos in about 1175/80—a typical way of getting rid of a rival, since ideologically an ‘imperfect’ man could not represent the divine as a ruler on earth. But there are two others who may have been sons or nephews of Ioannes: Andronikos and another Ioannes. The elder was declared a gambros, or kinsman, of Emperor Isaac II Angelos, the founder of the new dynasty that followed the Komnenoi in 1185. He had already been named sebastos by 1150, and was given the post of dux (military governor) of two provinces in Asia Minor in 1175. His (maybe) brother Ioannes rose even higher, despite being blinded by Emperor Andronikos I in 1183, by the new emperor, Isaac II, whose kinsman he more clearly was, having married his sister, Eirene Angelina, back in 1170. Isaac II appointed him caesar (the rank below sebastos) in 1185, gambros, then despot (a rank higher than caesar but still lower than sebastos), as military commander in Bulgaria in 1186. Another member of the family, Mikhael, perhaps a cousin, was involved in the conspiracy that deposed Emperor Isaac in 1195, and is perhaps the same Mikhael (a son of Ioannes and Eirene Angelina) who claimed the throne in 1199, but was imprisoned by the man who had taken it from Isaac II, his brother Alexios III…

This is all quite confusing, and made more so as most of these intermarried Byzantine dynasties took various forms of each other’s names, so tying one person to a specific dynasty is difficult—usually they had a string of names: Komnenos Dukas Angelos, etc. Indeed the next family member to rise to prominence was Ioannes Komnenos Angelos Kantakouzenos. He was given the court office of Pinkernes (cup bearer) in 1242, then was appointed Dux of Thakesion in Asia Minor in 1244. He governed here on behalf of the ‘rump’ of the Byzantine Empire based in Nicaea, for whom he defended the coast against the Latin rulers who had taken over the bulk of the Empire in 1204. More importantly from a dynastic point of view, Ioannes married Eirene Palaiologina, daughter of the Megas Domestikos, the commander-in-chief of the army of Nicaea, and sister of Michael VIII who would eventually drive the Latins out and restore Greek rule in Constantinople in 1261.

Eirene is actually the more interesting person in this story. Before he died, her husband Ioannes retired to a monastery, a common practice, and Eirene became a nun. After her brother became Emperor, she was an important influence on his early reign, but opposed his religious policies that favoured a proposed union with the Western Church in 1277, for which she was imprisoned. She thereafter became the focus of the opposition to Michael VIII’s reign at the court of her son-in-law, Ivailo, Tsar of the Bulgarians. Her daughters played an interesting part in this first reign of the Palaiologos dynasty as well: Theodora, also a widow-nun, was arrested with her mother in 1277 for opposing her uncle. She later restored the Church of Saint Andrew of Crete in Constantinople and made it her political base in the capital. Her sister Maria Kantakouzene was married in 1269 to Konstantin Tikh, Tsar of the Bulgarians, who became paralysed soon after and left much of the governing to his wife—she too led the opposition to the religious policies of Michael VIII; ruled as regent for her son, Tsar Michael II of Bulgaria, 1277-79; then married her husband’s killer, the leader of a peasant revolt named Ivailo, who then became Tsar of Bulgarians. In 1279, his reign was ended by a Mongol and Byzantine invasion, and Maria was taken back to Constantinople as her brother’s prisoner. Nearly two decades later, however, under the new Palaiologos emperor, Andronikos II, the third sister, Anna Kantakouzene, once more took power over a neighbouring territory, the Despotate of Epirus, in the name of her son Thomas Komnenos Dukas, until about 1313.

What we don’t have is a clear link between these powerful Byzantine women and Mikhael Kantakouzenos, the father of Emperor John VI. It is assumed he was a cousin, and his kinship with the imperial family was strengthened by his marriage to Theodora Angelina Palaiologina, possibly a niece of Emperor Michael VIII. Kantakouzenos was appointed Epitropos (steward or governor) of Morea, the southernmost part of Greece, in 1308. It was his son Ioannes who would make the biggest mark in Byzantine history for this family.

In 1321, Ioannes Kantakouzenos aided a young Prince Andronikos Palaiologos in rebellion against his grandfather Emperor Andronikos II, and by 1328, he was himself de facto ruler of the Empire as Megas Domestikos for the young prince, now Andronikos III. His high rank was made even higher with the fabulous new title ‘Panhypersebastos’ in 1340. When the Emperor died in June 1341, he was succeeded by his nine-year-old son, John V, and Kantakouzenos was proclaimed Regent of the Empire, but was opposed by powerful figures including the Patriarch and the boy’s mother, Anna. Ioannes left the capital to defend the frontier in Thrace against the Serbs, and declared himself co-emperor in October, as John VI. I’m guessing it is one of the only times in history when two people with the same name served as king or emperor at the same time. A civil war raged until John VI was victorious over John V and changed his position from junior co-emperor to senior co-emperor in 1347. Over the next few years he placed family members in key positions all across the Empire: his eldest son Matthaios, already Governor of Thrace, was named co-emperor in 1353; his second son Manuel, was Eparchos (city governor) of Constantinople, then Despot of Morea (and married to the daughter of the King of Armenia); while a cousin, Nikephorus, was Governor of Adrianopolis. Of his daughters, the younger, Helena, was married to John V and thus became empress; while the elder, Theodora was married to Sultan Orkhan, the second ruler of the new Ottoman state emerging in Anatolia. This must have been quite a shock for a Christian princess.

This points to a new alliance being forged: John VI and Sultan Orkhan versus John V and the Serbs. When civil war broke out again in 1352, Turkish forces took their spoils, and the Ottomans gained their first foothold on the European side of the Bosporus. The Turks had their first major victory on European soil at Demotikos, near Adrianopolis, and John V’s forces were vanquished. Matthaios was now formally crowned as co-emperor (Matthew I) in 1354, but the tide was soon reversed and by the end of the year, his father John VI was driven from Constantinople and forced into a monastery, then later into exile at his younger son’s court in the Morea, where he dedicated himself to writing books on history and theology, and died nearly thirty years later.

By this point, Morea was virtually an independent state with its capital at Mistra, run by Despot Manuel Kantakouzenos. Emperor Matthew settled here after he too was defeated by the alliance of John V and the Serbs, in 1357. After Manuel died in 1380, Matthaios declared himself the successor as Despot in Morea, but was run out when the real governor arrived from Constantinople in 1382. John V died in 1391, leaving as the last person standing in all this his wife, Empress Helena Kantakouzene, who became a nun (‘Hypomone’), then re-entered politics in 1393 as Regent of the Empire when her son Emperor Manuel II was absent from the capital.

Matthaios had two sons, both given rank of ‘despot’, the younger of these, Demetrios, also trying to continue the family rule in Morea in 1382-83. By the 1390s, the family’s power had all but dissipated. A grandson of Emperor John VI, Theodoros, was Byzantine ambassador to France and to Venice, where he was honoured with the title Patrician, 1387, and Senator, 1409—the Venetians being keen to maintain solid alliances with families of influence particularly in Morea, where they had colonial interests. His children made a bit of a comeback, with daughters marrying a Serbian prince, a Georgian king (though which one I cannot determine), and an emperor of Trebizond—a subsidiary Greek state on the northern coast of Anatolia—and sons occupying posts in the Byzantine government and army (though one, Thomas, became a commander of Serb armies, and is listed as marrying a daughter of the Emperor of Germany…but who?). The family tree is quite extensive at this point with many named in various positions in the defence of Constantinople in its last days as capital of the Eastern Roman Empire. Ioannes Kantakouzenos was a general for Konstantinos Palaiologos in Morea, and then helped him ascend the throne as the last Byzantine Emperor, Constantine XI, in 1449. His cousin Andronikos Kantakouzenos was the last Megas Domestikos for Constantine XI, and was executed after the fall of the city in May 1453 to Sultan Mehmet II ‘the Conqueror’, along with many others from this family, including his son Theodoros. His brother Giorgios, survived, and is the potential link to the later Cantacuzino family.

Giorgios Kantakouzenos, known as ‘Sachatai’—a Turkish nickname, though none of the online sources suggest what it means—had travelled quite a bit in the 1430s-40s, to the courts of Morea, Trebizond and Serbia, the last as brother-in-law of its ruler, Djuradj Brancović, who appointed him archon (governor) of the Serb capital, Semendria (today’s Smederevo) in 1454. Of his sons, the eldest, Theodoros, continued to live in Serbia in the 1450s; his second son Manuel was proclaimed ‘Despot of Albania’ by rebels in the Peloponnese in 1453-54; and his fourth, Demetrios, returned to Constantinople where, in about 1466, he was appointed ‘Domestikos’ of the Orthodox Church. Daughters in this generation continued to make useful alliances: with Venetian or Ragusan lords, with an emperor in Trebizond, with a duke of Saint Sava (what is today Hercegovina), and so on. One of Demetrios’ sons, Theodoros, married an Italian woman, and had children, but details about them are not known—one of these is thought *perhaps* to be Michael ‘Son of the Devil’, from whom all modern Cantacuzinos descend.

This ‘Son of the Devil’, or Şeytanoğlu in Turkish, Michael Kantakouzenos, was a wealthy Ottoman magnate who dominated the affairs of the Orthodox community in Constantinople in the middle of the sixteenth century, and acted as a conduit between them and the court of the Sultan (who gave him the title ‘archon’). He was very rich, enjoying monopolies on certain items in the capital city (notably saltworks), fisheries along the Black Sea coast, and the fur trade with Muscovy. His fellow Christians saw him as rapacious and cruel and gave him his nickname. In the 1570s, he extended his reach to the Balkan provinces where he was a tax farmer, and built his own Black Sea fleet to look after his fisheries and fur trade. He built a huge palace along this coast, in Anchialos (now Pomorie, Bulgaria). As he extended his reach economically, so too did he extend his reach politically, becoming a ‘king maker’ for the two Romanian principalities (Wallachia and Moldavia) and of the various Greek bishops and even patriarchs of the Orthodox Church. It is possible that Iane Kantakouzenos of Zagori was his brother (or cousin), and was placed as Ban (viceroy) of Oltenia, the western half of Wallachia; while a certain Theodora Kantakouzine was the mother of Prince Michael the Brave, the temporary unifier of all of the Romanian principalities in the 1590s—Prince Michael called Iane ‘uncle’, so Michael Kantakouzenos may have been his uncle too. In any case, Şeytanoğlu married as his second wife a daughter of Mircea III, Prince of Wallachia (of the family of Dracul), thus firmly moving his family from merchants to princes.

But Archon Michael didn’t live to see this. In 1576, he was accused of plotting against Sultan Murad III, arrested and hung from an archway of his own palace in 1578. There’s always a lesson to be learned from reaching too far too fast.

Michael’s son Andronikos (Mihaloğlu Derviş, Turkish for ‘son of Michael’ and ‘holy man’) managed to regain much of his father’s confiscated wealth, and returned to the task of integrating himself within the Romanian political elites (so is known in their histories as Andronic). He became a boyar in Wallachia, then Ban of Oltenia in 1592, and finally Co-Prince of Moldavia (with his perhaps cousin Michael the Brave), May to June 1600. He gained lands in Buzău County, on the borders between Wallachia and Moldavia, and a house in Târgovişte, the old capital of Wallachia. He managed Michael the Brave’s diplomatic affairs with Western Europe, but during that Prince’s rebellion against the Sultan in the summer of 1600, Andronikos went back to Constantinople and disappeared—perhaps he was executed, or perhaps he retired into a monastery.

There were at least three sons, but I’m unsure what order they go in. Possibly the eldest, Georgios, Gheorghe or ‘Iordaki’ in Romanian, returned to Moldavia and became ‘Grand Treasurer’ and chief of its armies in the 1630s-40s. He married twice, to daughters of local boyars, and founded the Iordaki Branch (or Moldavian Branch) of the Cantacuzino family. His brother Konstantinos or ‘Kostaki’ went south and became ‘Grand Boyar of Wallachia’. He married the daughter of one of the most influential local families, Elena Bassaraba-Craiovescu, daughter of Prince Radu Şerban of Wallachia, and founded the Kostaki Branch (or Wallachian Branch) of the family. Konstantinos was strangled in 1663 by the rival Ghica family, but his wife managed to keep her sons safe and re-established their power by the next decade.

The first genuine prince in the family, though, was the son of the third brother, Michael (Mihalis): Demetrius (Dumitraşcu) was appointed by Sultan Mehmet IV to the post of Hospodar or Prince of Moldavia in 1673, though only for a few months, then was reappointed again briefly in 1675, and again for over a year 1684-85. This time he was driven out by his general, Constantin Cantemir, about whom I’ve written elsewhere. Prince Demetrius returned to Constantinople and died, and did not start a separate branch like his brothers.

The Wallachian branch is more extensive and reached higher ranks, so it will be simpler to start with the Moldavian branch, perhaps on the assumption that it was the senior line anyway. I am unclear when they began to call themselves ‘prince’—as with several other local families from whom were drawn successive hospodars or voivodes (seemingly interchangeable terms that are translated either as governor, viceroy, or more elevatedly, as prince) of the Romanian principalities. They are also referred to as Phanariots, the name given to Greek families who lived in Phanar, a quarter of Constantinople, who now increasingly were sent by the Ottoman sultans to rule subject Christian populations in the Balkans.

Many members of the Moldavian line took the name of its founder, Iordaki (sometimes given as Iordache). Right away they divided into two lines: the Cantacuzino-Deleanu, for their chief estate at Deleni and the Cantacuzino-Paşcanu at Paşcani

The older of these residences, Paşcani, was built in the mid-seventeenth century by the Grand Treasurer Iordache. This was located in Iaşi County, west of the city of the same name (known historically as Jassy, the capital of the Principality of Moldavia), towards the slopes of the Carpathians that separate Moldavia from Transylvania. In 1812, the mansion passed into the hands of other noble families, who held it until private properties were expropriated by the Communist government in 1948. The house became the home for a Pioneer Youth Club (part of the movement all across the Eastern Bloc to educate future party members); today it belongs to the Ministry of Education, but is dilapidated and need of restoration.

A short distance away, closer to the mountains, this branch of the family also acquired (by marriage in the early seventeenth century) the Şerbeşti estate and its manor house, now called the Iordache Cantacuzino House, in a town now called Ştefan cel Mare. A second floor was added in the nineteenth century; today it is a school.

The other branch’s residence at Deleni was built in 1730 on an estate acquired earlier in the century, further to the north but still in Iaşi County. This mansion also passed out of the family at the end of the eighteenth century, by marriage, to the Ghica family who held it until World War II. Soviet soldiers occupied it for two years and burned much of the interiors. Over time it was transformed into a cultural centre, and now a medical facility for the town.

The Cantacuzino family also owned residences in the city of Iaşi itself. The Cantacuzino-Paşcanu Palace, built in 1780, was the Moldavian branch’s primary residence for a century, then became the City Hall in 1912. In 1970 Iaşi City Hall moved into a larger building, so this became the Registry Office. There is a statue of another Romanian prince, Cantemir, who lived in an earlier palace on this site.

In another part of town was the Cantacuzino House, built in in 1840 in grand style by the Grand Chancellor, Dumitrache Cantacuzino. In 1875, it was acquired by the Romanian royal family who used it as their principal residence when visiting Iaşi, their second capital after Bucharest; during World War I it became the principal residence of Queen Marie (the best-known Romanian queen to English readers, as a grand-daughter of Queen Victoria) when Bucharest was occupied by foreign armies. It too became a ‘Palace of Pioneers’ in the Communist era, and since 1989 has been converted into the ‘Children’s Palace’.

Iordache, Lord of Deleni, was Grand Chancellor of the Principality of Moldavia in about 1740. His grandson Matei moved to Russia in 1791 and was recognised formally as a prince by Catherine the Great, and given the post of Councillor of State. He and his sons moved back to Moldavia in 1812, though by this point it had been annexed to the Russian Empire. The next generation was thoroughly Russified: the eldest son Grigori, a colonel in the Imperial Guards, had been killed defending Russia at Borodino (1812), while the youngest, Egor, was married to a sister of the Russian Chancellor, Prince Gorchakov. It was the middle son, Alexander, a chamberlain at the Russian court, who redirected the family’s energies back towards Moldavia when he joined the fight for independence, first in Moldavia, 1821, and then in Greece, 1829, where he bought up some of the estates of retreating Turkish magnates, including Tatoi, near Athens, which after 1872 became the private residence of the Greek royal family.

Prince Alexander had a number of sons. Mikhail was an officer in the Greek and Russian armies, maintaining links with both states as Marshal of the Nobility of Bessarabia (the part of Moldavia still in the Russian Empire), and son-in-law of the Prime Minister of Greece in the 1830s; he then became a politician in the new state of Romania, as it forged its independence from the Ottoman Empire in the 1850s-60s (from 1858 known as the ‘United Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia’, and after 1862, the ‘Romanian United Principalities’, still a vassal state of the Ottoman sultans). His brother Alexander (Alexandru in Romanian) took a more prominent role, as Minister of Foreign Affairs of the new state, June to September 1862, and Minister of Finance, July 1862 to March 1863.

Other family members stayed in Russia: Mikhail and Alexandru’s nephew Prince Grigori was a diplomat in the United States (1892-95), then in the Kingdom of Württemberg, where he died in 1902. A cousin, Mikhail, a lieutenant-general in the Russian army, tied himself to the Imperial family by marriage to Olga, an illegitimate daughter of Grand Duke Nikolai Nikolaievich (a younger son of Tsar Nicholas I). Another cousin Mikhail was appointed Bulgaria’s Minister of War in 1885, a year when Russia tried to completely dominate its Balkan protégé’s government—but he was run out with all the other Russian officers following a coup in Sofia. Still other cousins from this branch devoted themselves to the new nation of Romania: Ioan Alexandru was one of the last caimacams (Turkish governors) of Moldavia, 1858-59, and later served as Minister of Finance of the Principality of Romania in 1870, and then its envoy to France and to Serbia; his nephew Constantin was a prominent leader of the conservative party in Romania after it declared its full independence from the Ottomans in 1877, and was elected President of the Assembly of Deputies in 1907 and again in 1912-14, after which he was appointed to the Crown Council, where he urged the King to remain neutral in World War I, then changed his tune to press for Romania to join the Allies in 1916 (which it did). Most of the Cantacuzino marriages in this period, male and female, were to other Romanian princes of this class: Callimachi, Stirbey, Ghika, Sturdza. The last male princes of this (Moldavian) line died in the 1920s.

Now turning to the Wallachian branch (or the Kostaki branch), we see the sons of the murdered Grand Boyar Konstantinos Kantakouzenos flourishing in Wallachia in the late seventeenth century. The eldest, Serban—named for his grandfather, Prince Radu Serban of Wallachia—was himself appointed by the Sultan as Voivode (or Prince) of Wallachia in 1678. He was noteworthy in his support of early Romanian nationalism, in ordering a Romanian translation of the Bible and abolishing the old Slavonic liturgy in Wallachian churches. Forced to support his Turkish overlords at the siege of Vienna, 1683, he made secret plans to join the Christian side—this failed, and a few years later he was poisoned by his brother Constantin. Constantin was the ‘Vel Stolnic’ or High Steward of Wallachia, a humanist scholar and early historian of the Romanian people. He was offered the job of voivode by the Sultan in 1688 (I guess in thanks for offing his brother), but preferred to stay behind the throne as an advisor for his sister’s son, Constantin Brancoveanu, and after his death in 1714, for his own son, Stefan. Prince Stefan II was the last semi-independent Prince of Wallachia, and had been involved in the downfall of his cousin in 1714, denouncing him to the Sultan for double-dealings with the Russian tsar. But Stefan in fact had plans of his own, to put Wallachia under Austrian protection—he managed to temporarily do so with the help of Austrian troops led by Prince Eugene of Savoy in 1715, but he was soon arrested and he, his father, and his uncle Mihai were all taken to Constantinople and beheaded.

Meanwhile, their cousin Toma had filled the Wallachian court offices of Grand Postelnic (Chamberlain) and Grand Spatar (Sword Bearer) under Prince Constantin Brancoveanu, until he led the Wallachian cavalry in support of Russia against the Ottomans in 1711; after Russia’s defeat in 1712, he fled there (similar to Cantemir…see that blog post). In Russia, Prince Toma was created a count of the Russian Empire, and appointed a major-general in the Russian army and commander of the citadel at Rostov guarding the River Don. He did not leave children to form a Russian branch, but his nephews did: Matei, and Prince Stefan II’s sons, Radu and Constantin. Of these two sons, the latter was formally recognised as a prince of the Russian Empire, and was a major-general in the Russian army; although he had two sons, his line died out in 1781. I’ll pick up the Russian line of Prince Matei again below.

Prince Radu Cantacuzeno was one of the most interesting members of the family. After his father’s execution in 1716, he and his younger brother were taken by their mother to Vienna where they obtained a pension from the Habsburg emperor and a promise that if Austria liberated Wallachia again, Radu (or Rudolf in German) would be placed on its throne. This did not materialise, so Radu, in desperate need of funds, began to use his family’s exotic-sounding name and mostly unknown past to his advantage as an entrepreneur. He was the first to assert clearly that his family descended from Emperor John VI, and published a genealogy, with a few invented names filling in the gaps. He changed his coat of arms from the earlier arms depicting an eagle holding a cross, to an expanded version with quarterings representing various Byzantine imperial dynasties and Romanian regions, a version still in use by the family today.

As a self-proclaimed claimant to the imperial title of Constantinople, he revived a supposed Constantinian order of chivalry, the Order of Saint George (which by all accounts was entirely invented in the sixteenth century, since the Byzantine Empire had no chivalric orders), and as its Grand Master, sold knighthoods to members of the Austrian nobility. He may even have been recognised as Grand Master by Emperor Charles VI (in part to challenge the other claimant to the grand mastership, Charles, King of Naples, son of his onetime rival for the Spanish throne). On his faked diplomas he used the titles ‘Prince of Wallachia, Moldavia and Bessarabia, despot of the Peloponnese, prince of Thessaly…’ and so on. He managed to create a small army, the ‘Illyrian Regiment’ in 1736, which he and his brother led all over the Balkans trying to start revolts to claim thrones in Wallachia or Serbia. By 1744, Charles VI’s daughter Maria Theresa was in charge in Vienna and was less impressed with Radu’s lofty claims, and more concerned with his mounting debts and disruptions caused to her diplomatic efforts to maintain the peace with the Ottomans. She declared his chivalric order fake and ordered his arrest—he fled abroad but his brother Constantin spent forty years in prison in Hungary then went to Russia as above. Prince Radu travelled all over Europe, from Berlin, to Paris and Venice, and died in Poland in 1761.

Meanwhile the senior line of this family, the descendants of Prince Serban I, remained more fixed in Wallachia. Serban’s son, Gheorghe (or Iordache), as a child was pushed forward by the Austrians as his father’s successor, unsuccessfully, then appointed Ban of Craiovia, the part of western Wallachia that had come under Austrian rule (1718-26). His eldest son Matei was created an Austrian count and established a branch that persisted there until 1883. The younger son Toma established a branch that also moved closer into the Austro-Hungarian sphere by becoming became lords of Corneni, near Cluj in Transylvania (then part of Hungary). The Cantacuzino-Corneanu continue to the present.

Other lines remained in Wallachia and, as they divided, took on nicknames to differentiate themselves. Gheorghe Cantacuzino-Rafoveanu was Minister of Finance of the Kingdom of Romania, 1895-98; while his cousin, Gheorghe Cantacuzino-Grănicerul (known as ‘Zizi’; his nickname Grănicerul means ‘the Border Guard’, from his time serving on the border in the war), a nephew of Gheorghe Manu, Prime Minister in 1890, became a Romanian general in World War I, then a conservative member of parliament. In 1934, he became President of the pro-fascist Nationalist Party, and briefly led a legion in Spain in the army of General Franco. His sister Ioana was an aviator, the first woman pilot in Romania, while their brother Ioan entered the world of the theatre through his marriage to actress Maria Filotti, a prolific stage performer, longtime teacher at the Conservatoire and between 1939 and 1948 director of the National Theatre in Bucharest. Their son Ion Filotti Cantacuzino continued in this vein, as a writer and film producer. He made short films for the Romanian war department in World War II, which caused him to be blacklisted after 1945 when the Communists took over. He had two sons, Georghe, a historian with specialisms in heritage and archaeology (monasteries), who served as chief museologist of the National Museum of Romanian History until 1990, then became an inspector at the Direction of Historical Monuments (d. 2019). The younger son, Şerban, became an actor in Paris in the 1990s (d. 2011).

It was in the line of Parvu (d. 1751) that the most significant leaders of the first decades of Romanian independence emerge. His two great-grandsons, Grigore and Constantin, saw the future of Romania in opposite visions. Both brothers served as Vornic of Wallachia, a court office in charge of justice and internal affairs. But Grigore became a leader of the nationalist liberals pressing for independence, and clashed with Constantin, a leader of the conservative boyar class who preferred the status quo: autonomy within the Empire. Constantin thrived in the government of Prince Alexander II Ghica in the later 1830s, as Postelnic and Logothete (Secretary of State and Justice Minister), but was unsuccessful in the election of 1842 to replace Ghica as prince. He joined the Ottoman army in 1848, and in return was named Caimacam (Regent) of Wallachia, 1848-49, and in the 1850s tried to obtain the princely throne again, as a champion of remaining under Ottoman rule. After Turkey’s defeat in the Crimean War, Prince Constantin was named Vice President of an ad hoc ‘Divan’, or caretaker government (and again in 1856). He tried once more to obtain the princely throne itself in 1859, but by this point the winds had changed, and outright independence was in the air.

Constantin the Postelnic built a family residence at Filipeştii de Târg, in one of the mountain valleys northwest of Bucharest, in a county called Prahova, where many of the later Cantacuzino residences would also be built. Today it is one of Romania’s chief tourist regions, and its old road leading across the Carpathians linking Wallachia and Transylvania is now travelled by those seeking access to ‘Dracula’s Castle’ at Braşov.

While Constantin’s son Ion became Minister of Justice for the new United Romanian Principalities and President of the Court of Appeals, it was his cousin, Grigore’s son, who made more of a mark: Prince Gheorghe Grigore was known as ‘Nababul’ (‘the Nabob’) due to his great wealth and grandiose lifestyle. He was a lavish builder: the Cantacuzino Palace in Bucharest, the Cantacuzino Castle in Buşteni and others. In government, he was elected mayor of the city of Bucharest in 1869, then held the posts of Minister of Finance (1873-75), President of the Chamber of Deputies (1889-91), President of the Senate (1892-95), and finally Prime Minister of Romania, twice, from 1899 to 1900 and 1906 to 1907, as head of the Conservative Party. In the later year, he failed to put down a major peasant revolt, so resigned.

In 1901, the Nabob built a colossal place in the northwest quarter of Bucharest in Beaux-Arts style, mixing in French classical and rococo influences. It has gates built to resemble those built for Louis XIV at Versailles. In 1913, it served as the site for the signing of the Peace of Bucharest with Bulgaria; and during World War II it was the residence of the President of the Council of Ministers. The Prince’s daughter-in-law later married Romania’s most famous composer, George Enescu, and since 1956 the Cantacuzino Palace has housed the Enescu Museum.

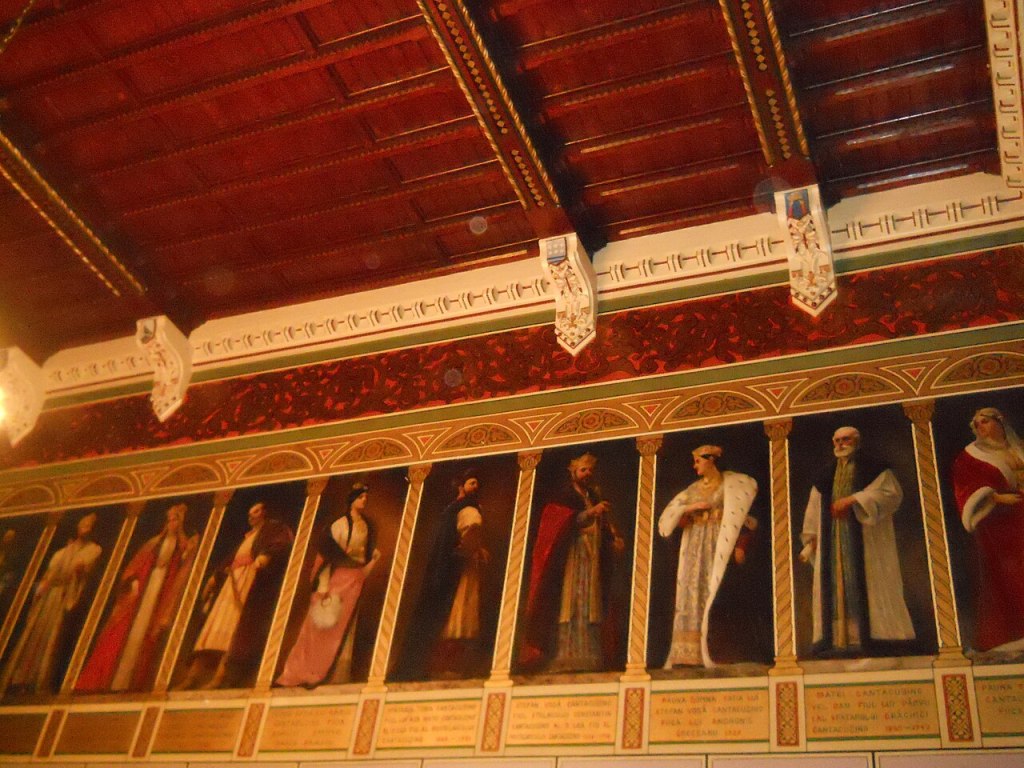

Meanwhile, up in picturesque Prahova County, the Nabob built Cantacuzino Castle at Buşteni, at the foot of the Bucegi Mountains. Completed in 1911, it served as a family summer residence and hunting lodge. Built in quite a different style to the city palace, Buşteni Castle, also known as Zamora Castle, is described as ‘neo-Romanian’, with lots of marble and mosaic, wood ceilings and friezes—lots of full-size family portraits and numerous coats-of-arms of various Wallachian noble families. Nationalised in 1948, it became a sanatorium; then after the fall of Communist regime in Romania, it was returned to Cantacuzino heirs who restored it and, since 2010, have opened it up as a museum—today one of the most popular tourist spots in Romania, and since 2022 seen on television screens all over the world as the setting for Nevermore Academy in the Netflix series ‘Wednesday’.

Finally, returning to his great passion for French architectural styles, the Nabob started a palace at Floreşti (not far from Buştemi), also known as the Romanian ‘Little Trianon’. This was started in 1911, but Prince Gheorghe Grigore died in 1913 before it was completed, and his son Mihail had little interest. So it deteriorated almost immediately. Pillaged in World War II then nationalised, the Floreşti Palace became a dog training facility. Its roof collapsed in the 1970s and villagers began to use the stones for other building works. Returned to the family in 1989, they decided it wasn’t worth saving, so it was sold to a private entrepreneur. He has plans to restore this strangely grandiose building the rural countryside, but it looks like they remain still only plans.

In the twentieth century, this branch continued to be eminent in various areas of public life: Ion’s son Ion (or ‘Iancu’), a physician and bacteriologist at the Romanian School of Medicine and Pharmacy, led campaigns against cholera and typhus in World War I; his cousins, Mihail and Grigore (sons of the Prime Minister), both served as Mayor of Bucharest in the years leading up to the First World War. Mihail later became Minister of Justice (1910-14 and 1916-18). They had prominent wives too: Mihail’s wife Maria (‘Maruca’), was a lady-in-waiting to Romania’s popular Queen Marie, and later in life re-married the famous composer George Enescu (as noted above). Grigore’s wife Alexandrina was a leading feminist in Romania in the 1920s, vice-president of the International Council of Women and representative for women’s rights at the League of Nations, but ultimately was pulled by her conservative aristocratic roots towards fascism (she and her circle became labelled as ‘nationalist feminists’).

In the next generation, Mihail’s son Constantin became an ace pilot in World War II; then, his lands confiscated by the postwar government in 1946, he settled in Spain with his wife, the Romanian actress Nadia Gray, who became a film star in French, English and Italian films, notably 1960’s La Dolce Vita. Grigore’s son Alexandru became a leader of the Fascist ‘Iron Guard’ in Romania in 1935, and fought with them in Spain, in support of Franco. He returned to Romania in 1937 where he was elected a deputy in the National Assembly, but was arrested in April 1938, on orders of King Carol II. He was released but plotted to overthrow the King that summer, so was arrested again in October—he refused to submit to a trial run by the royal regime and was executed in September 1939.

Finally we return to the branch of Cantacuzino princes established in Russia, where they were known as Kantakuzen or Cantacuzène in French (the language of the high aristocracy). This branch descends from Matei, son of Parvu. He was lord of Magureni in Wallachia—in Prahova County, as so many estates we’ve encountered already (suggesting this area was seriously infested with Cantacuzinos!), and also as with those estates, the Cantacuzino mansion in Magureni is now little more than rubble. Matei’s eldest son Constantin established a branch here (the Cantacuzino-Magureanu), which persisted into the twentieth century. Another Matei was a judge and professor of civil law in Iaşi at the end of the nineteenth century, mayor of that city, 1912-14, then a conservative member of the Romanian Chamber of Deputies, rising to national posts of Minister of Religious Affairs (briefly in Spring 1918) and Minister of Justice (also briefly, in Summer 1920); his son George Matei was an architect and painter, who moved to art school in Paris in the 1920s (so many of these Cantacuzinos we’ve encountered were educated in France), then returned to Romania to work on restoration projects of prominent buildings in Bucharest; from 1948 to 1953 he was a prisoner of the new Communist regime, then freed and joined the country’s directorate appointed to look after Romania’s historic monuments. But in 1957, he was again declared an enemy of the people and lost his positions—still he worked in historic restoration even as a blacklisted architect (for example for the Metropolitan of Moldavia); though he died in 1960s, interest in his worked was revived in the 1990s. He has a son, Stefan, who grew up in England and was a respected architect there.

The second son of Matei of Magureni, Parvu, was yet another Wallachian leader who revolted against Ottoman rule in the mid-eighteenth century, and, after succeeding in taking over the principality in 1769, was swiftly brought down and executed, within the year. It was his brother, the youngest son, Radu, who established the Russian line. Radu, also known as Radukan, or Rodion Matveievich in Russian, fought for Wallachia against the Turks in his older brother’s rebellion, then joined Russian service in 1770 and was appointed a colonel of a regiment he recruited in the Danubian principalities. He died in 1774 and left two sons, Ivan and Nikolai, the elder of whom moved back to Wallachia and into Austrian service, while Nikolai stayed in Russia and rose through the ranks. He was recognised formally by Catherine the Great as a prince in 1772, and was appointed colonel of different regiments (or ‘hosts’) of Cossacks in Ukraine. He established his family in an estate near Odessa, and acquired a residence in Saint Petersburg. I have no information about either of these residences, so would love to know more.

Prince Nikolai Rodionovich Cantacuzene’s son Rodion Nikolaievich was also a soldier, like his father rising to the rank of major-general. He raised the profile of this branch somewhat through his marriage to Princess Maria Alexandrovna Frolova-Bagreeva, the grand-daughter and heiress of the famous liberal reformer Count Mikhail Speransky, virtual prime minister of Russia under Alexander I in the Napoleonic era, and, while less influential under Nicholas I, was responsible for a huge codification project of Russian laws, for which he was awarded the title of count (and special permission to allow his grand-daughter to pass this title to her Cantacuzino husband and sons) in 1839. The name Speransky was ‘self-fashioned’ (he himself being illegitimate), from the Latin sperare (‘to hope’). Maria also brought with her the Speransky estate in Ukraine, Great Buromka, on the Buromka River southeast of Kiev. Once a great ‘Gilded Age’ mansion, only some ruins and the park of this once very grand estate remains today.

Rodion and Maria’s son Mikhail was confirmed as Count Speransky by the Tsar in 1872. An imperial privy councillor, he acted as Director of the Imperial Department of Spiritual Affairs and Foreign Confessions, a job he had interesting insights on as a descendant of Orthodox Greeks, but also married to Elisabeth Sicard a daughter of French Huguenots, merchants who had settled in Odessa. Their son, Prince Mikhail, Count Speransky, married an even more unusual bride: Julia Grant, granddaughter of the US president. They had met while he was a diplomat in Italy and married in a grand society marriage in Newport in 1899. In Russia, he was aide-de-camp of the Tsar at the start of World War I, the became a prominent cavalry general in the Russian defensive line in East Prussia. During the Revolution, he and his wife fled to the United States. Princess Cantacuzène published three fascinating books between 1919 and 1921 giving eye-witness accounts of the Russian aristocracy, the court in Saint Petersburg and the Bolshevik Revolution. In America, the couple’s marriage was annulled in 1934 and he died in Sarasota, Florida, 1955, while she lived on until the age of 99, dying in Washington DC (the city of her birth) in 1975. She is buried in the National Cathedral.

The Cantacuzène-Speransky line continues today, mostly in the United States, but with ventures elsewhere, one son, Mikhail, establishing a business in Mozambique then South Africa; a daughter, Zenaida, marrying Sir John Hanbury-Williams, Director of the Bank of England and a member of the households of George V and George VI; and a cousin, Pierre, born in France, who rose through the ranks of the Russian Orthodox Church in exile (as Father Ambrose) to become Bishop of Bishop of Vevey (1993, in Switzerland), Vicar for Western Europe (based in Geneva) then Bishop of Geneva and Western Europe, 2000-06 (d. 2009).

(images Wikimedia Commons)