On 3 October 2025, Henri, Grand Duke of Luxembourg, abdicated his throne in favour of his eldest son, Crown Prince Guillaume. The Grand Duchy of Luxembourg as an independent sovereign state has only had its own ruling family since 1890, though the Duchy of Luxembourg itself (and before that the County) is far more ancient, with roots stretching back into the eleventh century, and the Grand Duchy existed as an autonomous state within the Germanic Confederation, with the King of the Netherlands as its sovereign, from 1815. At that time, the dynasty that ruled the Grand Duchy was the House of Orange-Nassau, whose history has been traced here; after 1890, they were succeeded in Luxembourg by very distant cousins from the House of Nassau-Weilburg. One of the new Grand Duke Guillaume’s subsidiary titles is thus Prince of Nassau. But he and his siblings also bear another title: Prince of Bourbon-Parma, which makes the history of this ruling family even more interesting. Although they officially still are called the House of Nassau-Weilburg, strictly speaking from a traditional patrilineal perspective, they are Bourbons, members of the ancient House of France, with ancestry stretching back to the first Capetians in the tenth century.

An interesting twist, for those interested in historical drama on television, is that the actor currently playing Louis XVI in the series ‘Marie-Antoinette’, Louis Cunningham, despite lacking the heavy paunch and jowls of the real Louis XVI, certainly has a very Bourbon nose, and with reason—his mother is Princess Charlotte of Luxembourg, Princess of Bourbon-Parma, cousin to the current grand ducal family.

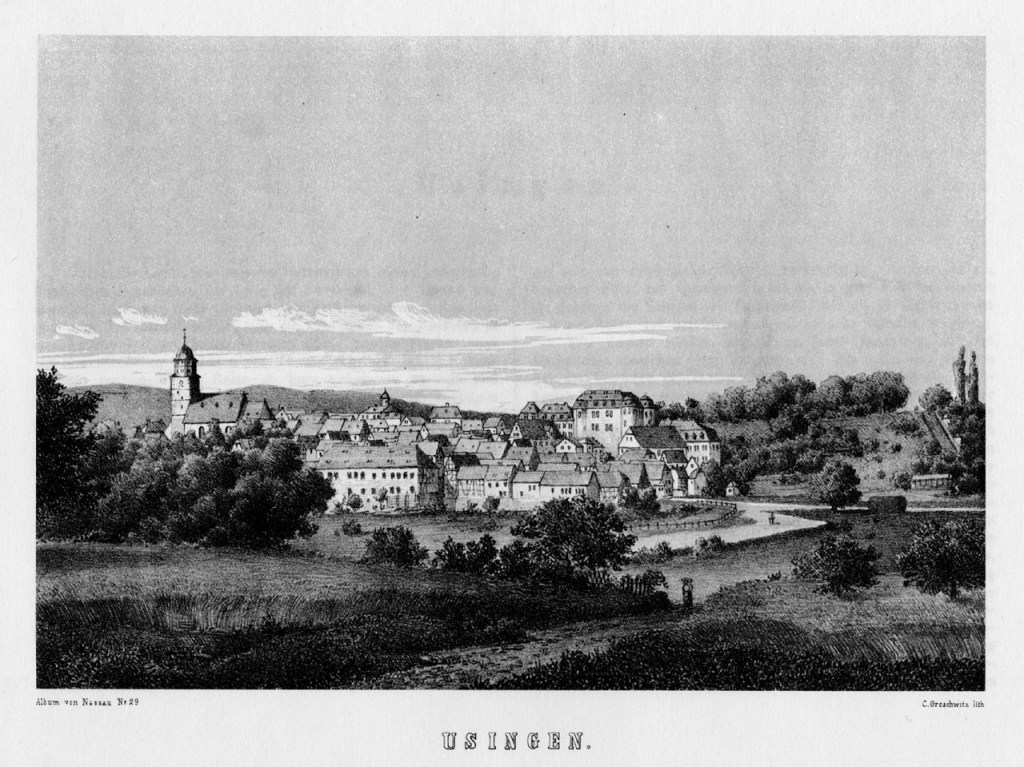

So how did this come about, that there are Bourbons masquerading as Nassauers in Luxembourg? This blog will look first at the twentieth-century dynastic history of Luxembourg and the Bourbon-Parma family, then will step back to look at the Princes of Nassau-Weilburg, one half of the House of Nassau. A previous blog has looked at the junior half of this dynasty, in its many branches that became princes (Dillenburg, Hadamar, Siegen and Dietz)—the last of these also became princes of Orange (a French territory they no longer possessed) in 1702, Dutch Stadtholders then kings of the Netherlands in 1815. As in Luxembourg, although the male line died out in 1890, the royal family there retains the name Orange-Nassau (rather than adopting Mecklenburg, Lippe or Amsberg for each successive spouse of a reigning queen). The branch of Weilburg also included other lines that also established principalities (Idstein, Usingen and Saarbrücken); and evolved into the relatively short-lived Duchy of Nassau, one of the new states created in the course of the Napoleonic Wars in Germany, but which disappeared in 1866.

To start, we can look at the strange circumstances in Luxembourgish history that followed the death of Grand Duke William IV in 1912. He and his wife, the former Portuguese Infanta Maria Anna, had six daughters but no sons. There were no other male members of the House of Nassau, in either of its two main branches—except the Count of Merenberg, but we’ll come back to him and the reasons for his exclusion. The Grand Duke passed a law that would allow him to be succeeded by his eldest daughter, Marie-Adélaïde. She governed the Grand Duchy for nearly six years, but in January 1919 abdicated in the face of her pro-German sentiment during the First World War. Her sister Charlotte, age 23, took over as Grand Duchess. A few months later, she married Prince Félix of Bourbon-Parma, and together they re-generated a grand ducal dynasty for Luxembourg, over which she presided until her abdication in 1964. Félix was her first cousin (he also had a Portuguese infanta as a mother), and although he was created ‘Prince of Luxembourg’ the day before their wedding, he retained his title Prince of Bourbon-Parma for the rest of his life—after all, the Bourbons outranked the Nassaus, and his children by right could now be called Royal Highness instead of Grand Ducal Highness. Why was this so? What or where was Bourbon-Parma?

It was not a place, but a branch of the royal house of Bourbon that ruled in the Duchy of Parma (and Piacenza, to give it its full name) from the 1730s to 1859, when it was annexed to the Kingdom of Sardinia (which soon became the Kingdom of Italy). The Bourbon Dynasty is of course one of the most well-known royal houses in Europe, ruling France from 1589 to 1848 (with some gaps), and Spain from 1700 to the present (with some gaps). In 1731, the son of the first Bourbon king in Spain (Philip V), Infante Carlos, sailed for Italy where he took possession of the duchies of Parma and Piacenza, ruled by his mother’s family, the Farnese, since 1545. Duke Charles I was not satisfied with this relatively small state, however, and in 1734, marched an army south to reclaim the kingdoms of Naples and Sicily, lost to his father at the end of the War of the Spanish Succession in 1713. Parma was then annexed by Austria, only to be returned to the Bourbons—to another son of Philip V and Isabel Farnese (Infante Felipe)—at the end of the War of Austrian Succession in 1748 (and with the addition of a third duchy, tiny Guastalla). Duke Philip was seen as an extension of the royal family of Spain, but his wife, Duchess Elisabeth-Louise, was the eldest and favourite daughter of Louis XV of France. Their son Duke Ferdinand of Parma was thus caught between the wills of the French and Spanish branches of the Bourbon dynasty, though he came to rely increasingly on his wife, an Austrian archduchess, Maria Amalia (an older sister of Queen Marie-Antoinette), and they forged a more independent path.

So by the time of the French Revolution, there were four ruling branches of the House of Bourbon—France, Spain, Naples-Sicily and Parma—plus some non-ruling branches like the dukes of Orléans and the princes of Condé and Conti. All four lost their thrones as a result of the French Revolution—though the Bourbons of Naples held on in Sicily throughout, and the Bourbons of Parma actually got a promotion, briefly, as kings of Etruria, a curious revival of an ancient name for a monarchy created in Tuscany by Napoleon as a satellite or dependant state of the French Empire (1801-1807). Norman Davies included this interesting puppet state in his book Vanished Kingdoms from 2012: ‘Etruria: French Snake in the Tuscan Grass’. The Bourbon-Parma family then had to wait until Napoleon’s widow, ex-Empress Marie-Louise died in 1847 before they were fully restored to Parma and Piacenza (in the meantime they were compensated with the smaller duchy next door, Lucca). By this point, Duke Charles II (who curiously had been called Louis II as child-king of Etruria) was hardly interested in governing, and abdicated in 1849 in favour of his son Charles III. This duke was assassinated in 1854, and his infant son Robert was deposed in 1859 by the unstoppable surge of the Italian Risorgimento. Unified Italy would soon take over in Naples and Sicily as well.

So after 1859, the Bourbon-Parma family was a ruling dynasty with nowhere to rule. Robert married twice and had twenty-four children. (yes!) The last of these, Zita, did not die until 1989, at 96 years old. Despite not having a throne, their royal blood and kinship ties to other royal houses still afforded them prestige and first-class marriages: in 1893, the eldest child Princess Maria Luisa married Ferdinand, Prince of Bulgaria (later Tsar), and in 1903, Prince Elias married Archduchess Maria Anna of Austria. A far more significant marriage occurred in 1911, when their half-sister, Zita, married Archduke Carl of Austria, heir to the throne after 1914, and they succeeded as Emperor and Empress of Austria, King and Queen of Hungary, in November 1916. Zita’s brother Prince Félix then married Charlotte, Grand Duchess of Luxembourg, in 1919, as we’ve seen. Her other brother Sixtus had already made his name somewhat a few years before, in what’s now known as the ‘Sixtus Affair’.

When World War I broke out, the head of the family, Prince Elias (known as Élie in French—like much of his family, or indeed his class, they preferred to speak and write to one another in French) served in the Austrian army, in an honoured position as brother-in-law of the Emperor Carl, as did his brothers René and Félix (the actual eldest brother, the titular Duke Henri, was in fact severely mentally disabled, as was the next brother, Joseph, so Elias had been appointed by the Austrian court as their guardian, along with several of their sisters, also disabled). In contrast, two of their half-brothers, Sixtus (or Sixte in French, as he was the 6th son) and Xavier, joined the Belgian army. In March 1917, Sixtus arranged a meeting via his sister Empress Zita in Switzerland between French officials and Emperor Carl, in an effort to make peace terms before Austria-Hungary crumbled altogether. The French had stipulations for the peace, notably the restoration of Alsace-Lorraine and the independence of Belgium, which Carl was unable to guarantee in the face of fierce opposition from his German allies. So nothing was finalised, and when news of the negotiations leaked to the press in April 1918, the Emperor denied involvement until French President Clemenceau published the relevant letters and documents. This weakened any influence the Habsburg emperor had in Berlin and only hastened the collapse of his empire.

Although the Bourbon-Parma dynasty had no throne, they had no shortage of money, inheriting not just private estates in Italy like the Villa Pianore near Lucca, but also the wealth of the senior branch of the House of Bourbon when it died out in 1883, notably several castles in Austria and the Château of Chambord in France (Duke Robert’s mother had been the sister of the last Bourbon, the Comte de Chambord). Since Elias had fought for the Austrians, his French estates were sequestered in 1915, then liquidated by the French state in the 1920s; this action was contested by his half-brothers Sixtus and Xavier, who had served in the Belgian army, allied with France, and therefore not subject to the same wartime sanctions. In 1925 the French government awarded them an equal share of the patrimony (what remained of it). Chambord, however, had to be sold to the state, for 11 million francs, in 1932. Elias succeeded as titular Duke of Parma in 1950, after the incapacitated Henri and Joseph died. His son, Robert II, then headed the clan until he died without a son in 1974.

Meanwhile, Prince Xavier had still other dynastic claims to press. Although he wasn’t the eldest son, in 1936 he was selected to act as ‘regent’ for the Carlist party in Spain. This is not the place to go into the history of Carlism in Spain, but in a nutshell, back in 1833, Infante Carlos, younger brother of King Ferdinand VII, refused to accept that the Spanish throne could pass to a woman and tried to block the accession of his niece Isabel II, and three Carlist Wars followed, very nearly toppling the government. After 1883, they also claimed to be the legitimate heirs to the French throne, as the senior lineal male descendants of King Louis XIV (though this hardly meant much given that France was now a republic). In 1936, the last of the Carlist pretenders died childless, so the Carlist organisation asked Xavier to be ‘regent’ and symbolic commander of their troops fighting in the Spanish Civil War (the actual king, Alfonso XIII, had been expelled in 1931). Xavier was not the next in line, lineally, but he did share the values of the movement, in its extreme devotion to conservative politics and the Catholic Church. He was expelled from Spain by General Franco in 1937; then arrested by the French Vichy government in 1944 and deported for having close links to the Resistance, and was incarcerated at Dachau until May 1945. From 1952, Xavier was named ‘king’ (Javier I) by leaders of the Carlist movement, though he himself shied away from it. In 1975, once he became titular Duke of Parma, he abdicated as ‘King of Spain’ in favour of his son Carlos Hugo (b. 1930), who became ‘Carlos VIII’.

So it would seem the senior branch of the Bourbon-Parma family should be mostly associated with Spain today, but that is not in fact the case. Carlos Hugo had married Princess Irene of the Netherlands, the second daughter of Queen Juliana. Their engagement in 1964 had caused a constitutional crisis, since the Dutch government refused to sanction the marriage due to his father’s claims to be a head of state. They were nevertheless married, in Rome, with the Princess converting to Catholicism and losing her succession rights to the Dutch throne. None of her family attended the wedding. They lived in Madrid until Franco expelled them in 1968, and so they moved to France. After 1981, Irene and Carlos Hugo were divorced, and she and her children lived in the Netherlands, at Soestdijk Palace. Her husband had re-engaged with the Carlist movement in the 1970s, notably trying to reform it after a neo-fascist attack on his more liberal supporters in May 1976 in Navarre (the ‘Montejurra Massacre’). In fact, Carlos Hugo was a socialist, totally at odds with the Carlist movement, so in 1979 he renounced his claims in favour of his brother, Sixtus Henry, a real devotee, regarded as a ‘standard bearer of tradition’, who now took the name ‘Enrique V’. Sixtus Henry (or ‘Don Sixto’) remains active in Far Right politics all over Europe and prefers to use the title ‘regent’ of the Carlists, rather than king, in hopes that his nephew might return to traditional ideology. This nephew, Prince Carlos (b. 1970), was raised in the Netherlands and married a Dutch citizen. Since 1996 he and his siblings have been formally recognised as part of the Dutch Royal Family. In 2010 he succeeded his father as titular Duke of Parma, but also took up the Carlist claim, as either ‘King Carlos Javier’ or the Duke of Madrid (the title used by previous Carlist pretenders). He acknowledges these various titles and styles, but makes no active claims on the Spanish throne. Instead, his energies are focused on Dutch environmental issues. His son, Prince Carlos Enrique (b. 2016), is known as the Duke of Piacenza.

There is still one more branch of the Bourbon-Parma family today: after the end of the First World War, Prince René married Princess Margaret of Denmark, daughter of Prince Valdemar (a younger son of King Christian IX). They lived in France in the interwar period, then in Denmark after 1945, and raised a number of children including Princess Anne who married King Michael of Romania in 1948 (just after he had abdicated that throne); and Prince Michel whose family are still considered distant extensions of the Danish royal family. Prince Erik in fact closed the circle somewhat by marrying his cousin, the daughter of Princess Marie-Gabrielle of Luxembourg, in 1980.

Returning therefore to the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, Charlotte abdicated in 1964 in favour of her son Prince Jean. His father, Prince Félix of Bourbon-Parma, had earned a prominent position in the Grand Duchy, notably as the president of the Luxembourg Red Cross, 1923-32 and 1947-69. He died in 1970 in Fischbach Castle—an estate owned by the Grand Ducal family since the 1840s, deep in the hills north of the city of Luxembourg. Charlotte died in 1985, the last member by birth of the House of Nassau-Weilburg (four of her five sisters had died relatively young). Two years later, Grand Duke Jean decided formally that his family would be known as the House of Nassau-Weilburg, not Bourbon-Parma—but this decision was reversed by his eldest son Grand Duke Henri when Jean abdicated in 2000. Both male and female members of the dynasty are now known as both prince/princess of Nassau and of Bourbon-Parma. The House of Bourbon-Parma continues to thrive as a royal house also through the marriages of some of its other members: Grand Duke Jean married the sister of the King of the Belgians, Joséphine-Charlotte; their daughter Marie-Astrid married a Habsburg, Archduke Carl Christian of Austria (a descendant of Empress Zita); and her sister Margaretha married Prince Nikolaus of Liechtenstein (younger brother of the ruling prince). In an interesting twist to the situation of her grandfather Félix, Margaretha is permitted to retain her HRH style, while her husband is a Serene Highness.

And so we can now step back to the early years of the Holy Roman Empire, to follow the path of the House of Nassau-Weilburg that led them from relatively minor counts in the Rhineland to one of the ruling houses of Europe.

As seen in the previous blog post about the princes of Orange (part 2), the counts of Nassau emerged in the early twelfth century as lords controlling much of the Lahn river valley as it flows between the Taunus mountains and the Westerwald into the Rhine in the middle stretch of the great river between Mainz and Koblenz. They shook off any ties of vassalage to the local bishops of Worms or Mainz, and were soon included amongst the imperial counts, that is, those with real autonomy and a voice in the imperial diet. In 1255, the family’s landholdings were divided between two brothers, Walram and Otto, and the two main branches of the dynasty were formed, with the Lahn acting as a north-south boundary between them. The senior line, the Walramians, took over the southern lands, notably Wiesbaden and Weilburg; while the Ottonians were based further north at Dillenburg and Siegen, and would eventually (three centuries later) acquire the principality of Orange and become major political players in the Low Countries, before becoming the royal dynasty of the Netherlands from 1815 to the present. One thing that makes this family really interesting is that even more than others of a similar rank, they always maintained a common dynastic interest: all branches, no many how many they bifurcated into, maintained joint ownership over the main castle of Nassau on the Lahn (even after it fell into disrepair); and several mutual succession pacts were signed, not just within the two sub-branches, but between the Walramian and Ottonian branches as well, which had significant ramifications, namely that the line of Nassau-Weilburg, Walramians, were called to succeed the line of Nassau-Dietz (or Orange-Nassau), Ottonians, on the throne of Luxembourg, even after six hundred years of separation. That’s really something.

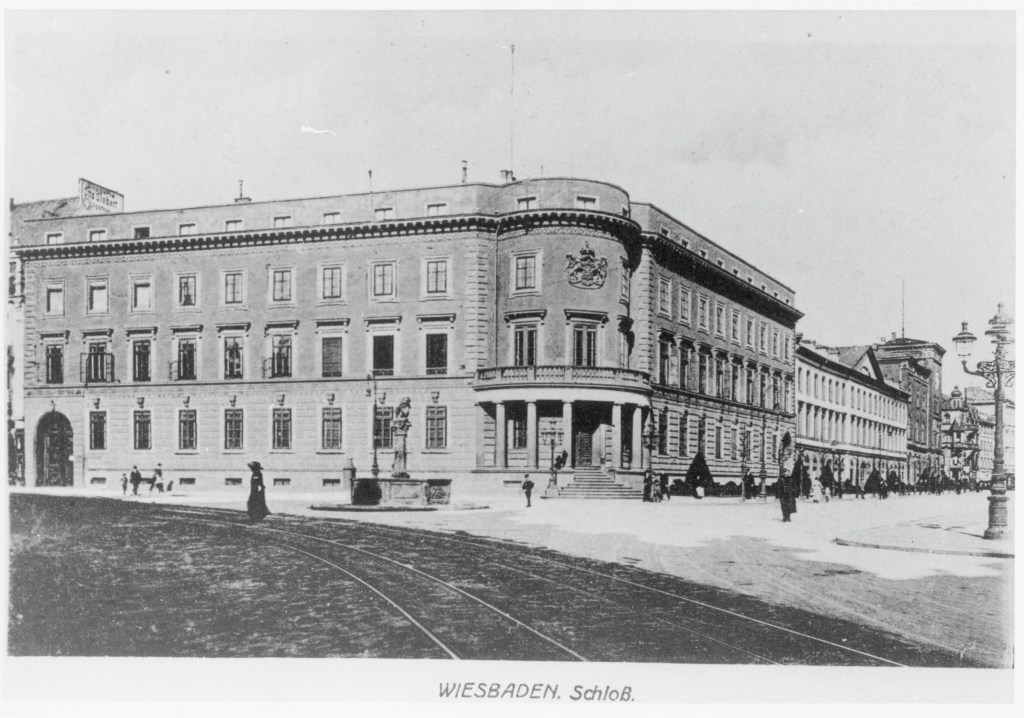

The first main seat of the Walramians was Wiesbaden, at the far southern end of the County of Nassau. This is a really interesting city, a spa town with gardens and theatres, located on the huge bend of the Rhine where it is joined by the river Main near the city of Mainz. The name gives it away that this was always a spa (‘baden’), and it had been a royal residence of Frankish rulers since the eighth century (this was in fact part of the ancient Duchy of Franconia). The Nassau counts acquired the town and built a new castle here in the 1230s, later developed as a renaissance palace in the sixteenth century, then fell into disuse in the seventeenth when the family base shifted elsewhere. Wiesbaden was revived in the nineteenth century when it became the capital of the enlarged Duchy of Nassau (see below), and its Stadtschloss (‘city palace’) was rebuilt as a neoclassical palace in 1841. It later became part of Prussia, and a favoured summer residence for Germany’s emperors—who also patronised the development of the spa, notably in its grand main building, the Kurhaus (1907), with baths, concert halls, casinos and restaurants. With the fall of the German Empire, the former Nassau palace served several functions: as headquarters for the British Army in the 1920s, seat of the Wehrmacht for the western districts of Germany in the 1930s, then headquarters for the US Army, 1945-46. Since 1946 it has housed the Hessian State Parliament.

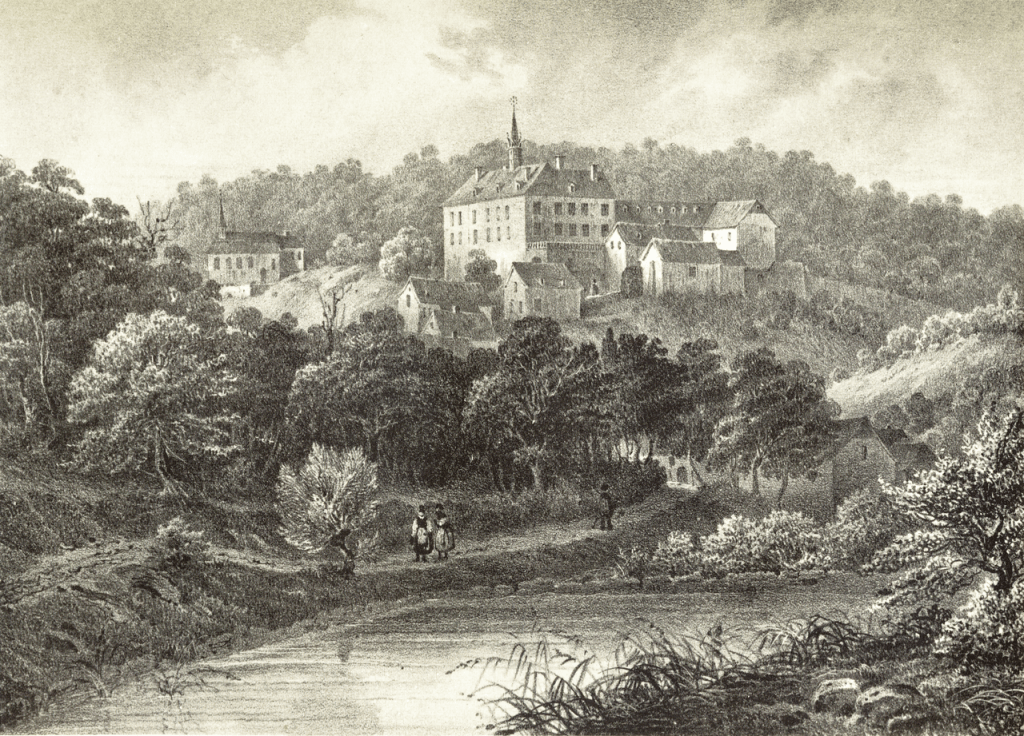

The other main residence of the early Walramian counts of Nassau was Weilburg. This castle sits in a loop of the river Lahn, near the mouth of a smaller river called Weil. Deep in the hills, it guards one of the ‘high roads’ (ie, not the roads following along the valley of the Rhine) between Frankfurt and Cologne. It too was an ancient royal foundation, as an abbey dedicated to St Walpurgis (tenth century), with a nearby royal residence, which the Nassau counts received in 1225 at first as vogts or advocates (secular defenders of ecclesiastical lands), on behalf of the bishop of Worms, but then sold to them outright in 1294. A new castle was built in the 1350s, replaced by a renaissance palace in the mid-sixteenth century, then upgraded again in baroque style in the early eighteenth century, and expanded with orangeries (two!) and an ornamental garden. This was the main seat of the Duchy of Nassau from 1806 to 1818 when it moved to Wiesbaden, and although these lands were also annexed to Prussia after 1866, the Nassau-Weilburg family continued to own the castle until sold to the State of Prussia by Grand Duchess Charlotte of Luxembourg in 1935 (the family still retains ownership of the dynastic burial chapel).

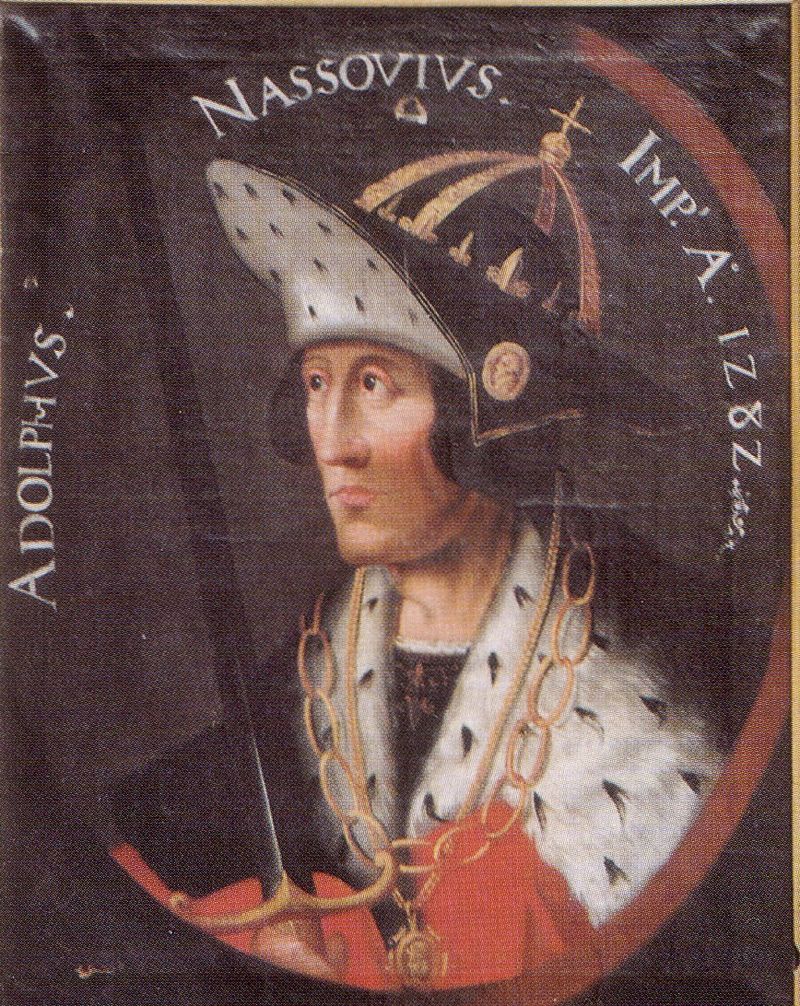

Both branches of the House of Nassau received a huge prestige boost in 1292 when Count Adolf was—to the surprise of many of the great magnates—elected King of Germany, the first step towards being crowned Holy Roman Emperor. This was the second time in a row the German princes had elected a relative nobody after the collapse of the Hohenstaufen imperial dynasty, with the idea that if the person occupying the top position in the Empire had little wealth and no large territorial base, he couldn’t be a threat. Count Rudolf of Habsburg had been the first, in 1273, but when he died in 1291 his supporters tried to elect his son Albert, now Duke of Austria, as his successor. This went against the idea of keeping a weak person on the throne, so opponents elected Adolf of Nassau. His father Walram II had been the marshal of the court of King Rudolf and a member of his privy council, and Adolf as a young man had also served at his court, and those of the archbishop-electors of Cologne and Mainz. So he was elected mostly by these Rhenish archbishops as a block to Albert of Habsburg, and he had to agree to many concessions and restrictions on his power. He very quickly broke all his promises however, making an alliance with the King of England against the King of France (which the archbishops opposed), and trying to build up his dynasty’s territorial base (as the Habsburgs had done) by annexing lands in Thuringia and Saxony, thus alienating the electors of Saxony and Brandenburg. By Spring of 1298, the princes had enough, and Adolf I was deposed, and Albert of Habsburg elected in his place—Adolf held on for a short while but was killed in battle against Albert near Worms in July.

Most medieval noble families raised themselves up the ranks by obtaining important episcopal positions, especially those noble families in the Rhineland. So the Nassauers’ position in imperial politics was saved following this disaster by the election in 1300 of Adolf’s brother, Diether, as Archbishop of Trier. His relatively short reign there was also pretty disastrous though, as he made enemies of the new emperor (Albert), of his own chapter and citizens in Trier—even leading to violence—and ruined the electorate’s finances. He died in 1307. A more sustained run of ecclesiastical power for the House of Nassau was in Mainz, where King Adolf’s son Gerlach was Archbishop for a long time (1346-71)—including the crucial period when the final number of imperial electors (including himself) was determined by the Golden Bull of 1356—followed after a gap by his nephew Adolf, 1381 to 1390, then his brother Johann, 1397 to 1420, and finally another Adolf, 1461 to 1475. So for nearly 150 years, the Nassau dynasty controlled one of the three key archbishoprics in the Empire, Mainz, based just across the river from their seat at Wiesbaden. The Archbishop of Mainz was also the Imperial Arch-Chancellor, who presided over meetings of the prince-electors following the death of each king or emperor—though the House of Nassau was never again tempted to fill this seat themselves.

In the 1340s, like most German princely families, the Walramians divided up their lands between brothers, starting the sub-branches of Nassau-Weilburg and Nassau-Wiesbaden, to which was also called Nassau-Idstein. In 1366 all the members of the family were formally named as imperial counts (subject to no one but the emperor himself), and a few years later, another important territory was added to this branch, located much further to the west on the borders with France, the county of Saarbrücken. The lines of Weilburg, Wiesbaden-Idstein and Saarbrücken would be divided, re-united, and divided again many times over the next three centuries. But until they were elevated to the next step, imperial princes, I will only skim over the most pre-eminent members.

The senior line based at Idstein occupied a castle just a few miles north of Wiesbaden, in the Taunus mountains. Unlike many of the other Nassau properties, its medieval castle served as a residence almost continually between 1100 and 1721, and its twelfth-century Hexenturm, or ‘witches tower’, remains an icon of the town. A new residence was built in the early seventeenth century, but the older buildings were left intact. After 1721, the family moved to Biebrich, a new palace on the other side of Wiesbaden, so Idstein was used to house administrators and the comital archives.

The most prominent member of this branch was Count Adolf III, a supporter of Emperor Maximilian I in his efforts to govern his new territories in the Low Countries, for which he was appointed Stadtholder of Guelders in 1489. Succeeding generations were also involved in the politics of the Low Countries (and married into the nobility there), which interestingly mirrors what their Ottonian cousins were doing at the same time. This line of Wiesbaden-Idstein died out and the lands passed back to Nassau-Weilburg.

Back in the 1380s, a new territory, Saarbrücken, was inherited by Count Philipp of Weilburg, who became quite involved in German politics at the national level, appointed by Emperor Wenceslas of Luxembourg to maintain the peace in the Rhineland (and given the right to coin his money in his domains), then taking part in the deposing of this emperor, and of his successor, Rupert of the Palatinate. He later became a senior advisor on the council of Emperor Sigismund of Luxembourg, and was appointed by him to be hauptmann in Luxembourg, aka, leader of the nobility. When he died in 1429, Weilburg and Saarbrücken were divided between his two sons.

Saarbrücken has a fascinating history of its own, aside from its long association with the House of Nassau between the 1380s and the 1790s. As its name suggests, a county was formed around an important crossing of the river Saar (the river that gives its name to the Saarland, Germany’s most western, and smallest, state). But it’s possible that the word brücken does not come from bridges (like nearby Zweibrücken, ‘two bridges’), but in fact from an older Celtic term briga, ‘large stone’—and the river Saar itself takes its name from a Celtic word, sara, for ‘running water’. In French, this is known as the Sarre, and today it forms much of the boundary between German and French speaking areas, though in the past it didn’t—the language frontier was further west, within the Duchy of Lorraine. Nevertheless, this really interesting cultural frontier zone, the Saargau, fragmented early on in the history of the Holy Roman Empire, and spawned numerous tiny principalities like Saarbrücken (and nearby Saarwerden, which we’ll encounter below) in the area between the provinces we now know as Alsace and Lorraine. Several of these remained independent imperial enclaves even after the Kingdom of France had taken over both these provinces, and will feature in other future blogs (like Leiningen, Salm, or Hanau-Lichtenberg)—and when the Holy Roman Emperor was looking for a pretext to launch a war against the French Republic in 1792, the rights of these princes provided it. That included Nassau-Saarbrücken.

Saarbrücken was a county from 1080, at first as a vassal of the bishops of Metz, then as autonomous imperial counts. The County of Zweibrücken was carved out of its eastern parts in the thirteenth century, and had its own very interesting history—but that is part of the story of the Wittelsbachs of the Palatinate, not Nassau. The original dynasty of counts died out in 1233 (and similar to the House of Nassau, their prestige was boosted by having two archbishops of Mainz, Adalbert I and Adalbert II, between 1111 and 1141). A second dynasty died out in 1381, and passed Saarbrücken by marriage to the House of Nassau-Weilburg. This succession also brought them the lordship of Commercy, a real curiosity in that it was wedged between the duchies of Lorraine and Bar, yet legally subject to neither. Its owner was thus drawn much further west towards politics of the Kingdom of France—but the counts of Saarbrücken (probably wisely) sold this tiny sovereignty to the duke of Lorraine and Bar in 1444.

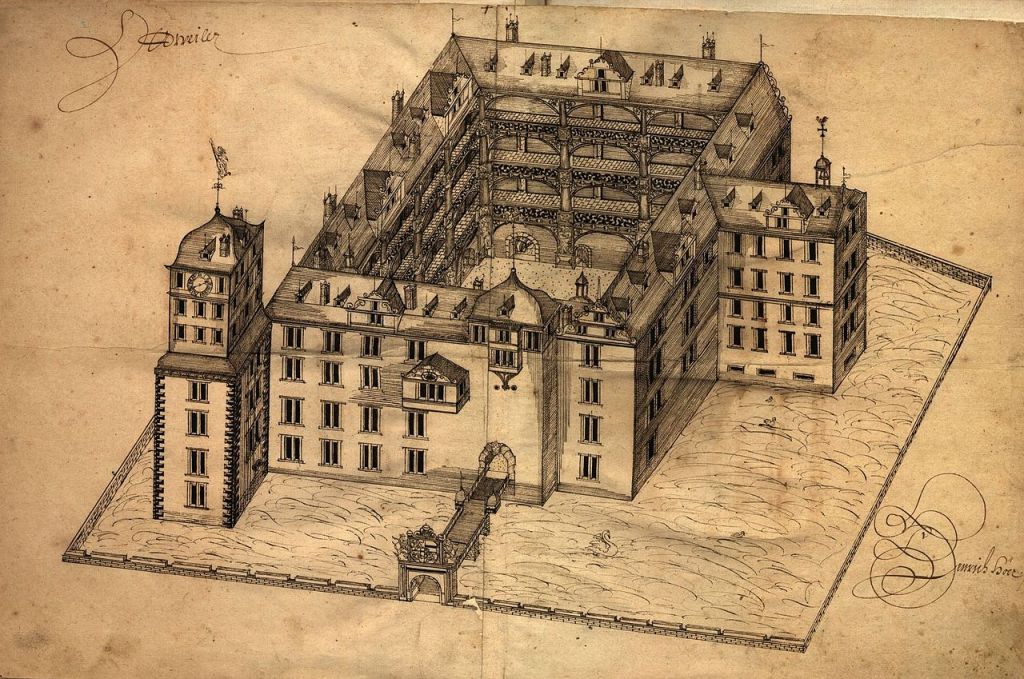

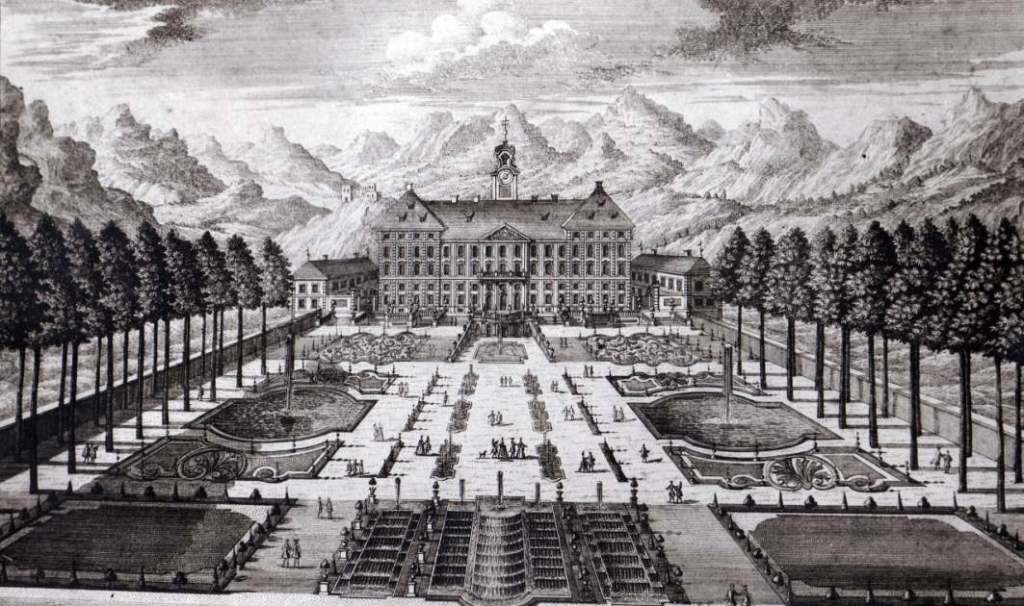

Saarbrücken had an ancient castle, since it was situated on high ground at a crossing of the Saar, a key river that flows northward to join the Mosel just above the city of Trier. This castle was destroyed and rebuilt many times over the centuries, then was developed into a more comfortable residence by Count Philipp IV in the late sixteenth century, primarily as a summer residence (in the winters, he lived back across the Rhine in Nassau proper). This residence was destroyed in war in 1677, and rebuilt by Count Louis Crato, who, in emulation of Versailles, opened up the courtyard so that the new palace faced the town. He also ordered French baroque gardens. His successor Wilhelm Heinrich built an even grander palace on this site, getting rid of the old medieval defensive structures, and planning an entirely new town, on a grid, with a palace for his heir, a city hall, and a grand public square called the Ludwigsplatz. Completed in 1748, this was a model town for the new ‘Enlightened’ style, organised and neat. He expanded the baroque gardens as well, and built wings on the palace to house his government and administrative archives (again, very much like at Versailles). Much of this was destroyed when the French chased the dynasty out in 1793, and after the Napolenoic Wars ended, Saarbrücken was not returned—the palace was converted into flats and the central pavilion demolished. In 1910 it was acquired by the Saarland district government. It served as a Gestapo headquarters during the Second World War, and was again badly damaged—totally renovated in the 1980s, a new central pavilion was built, with a very modern steel skeleton, and today it serves as the administrative centre for the Saarland.

There were numerous intermarriages between the branches of Nassau-Weilburg, Idstein and Saarbrücken, and also with their more distant cousins from Nassau-Dillenburg, Siegen and Dietz. Most of them (but not all) joined the Protestant movement in the 1530s, though some chose Lutheranism and others Calvinism and imposed these on their subjects in the County of Nassau. Count Philipp III of Weilburg created a new school in his town, the Gymnasium Philippinum, and was a close ally of his neighbour, Landgrave Philipp of Hesse, one of the leaders of the reform movement in central Germany. As part of their alliance, they exchanged some territories between Nassau and Hesse, notably parts of the old medieval County of Katzenelnbogen, situated on both sides of the great bend of the Rhine (which I always thought gave its name to this ‘cat’s elbow’, but apparently not). The Katzenelnbogen family had died out in 1483, and the houses of Nassau and Hesse fought over the succession in the imperial lawcourts for over fifty years (the wonderfully named Katzenelnbogische Erbfolgestreit, or ‘Katzenelnbogen Succession Struggle’). It is worth pointing out, however, that it was an Ottonian branch of the Nassauers that claimed this land, not the Walramians; and although they ultimately lost the lawsuit, they continued to use the title ‘Count of Katzenelnbogen’, which eventually passed into the collection of titles still used by the Dutch royal family today. In 1815, the old County of Katzenelnbogen was added to the new Duchy of Nassau (to compensate for lost lands west of the Rhine), and so after 1890, the grand dukes of Luxembourg also started to use this title when listing all of their dynastic titles. And so it appears in lists today in the titles of both the kings of the Netherlands and the grand dukes of Luxembourg today. Isn’t that peculiar?

As Philipp of Hesse lost influence in the 1540s, Philipp of Nassau worked to construct an alliance of small counts in this part of the Empire, known as the Wetterau Association. As the reform movement progressed, Philipp dissolved the ancient Abbey of Weilburg (and others) in the 1550s.

Meanwhile, the County of Saarbrücken was still Catholic. In 1527, the territory of the Nassau-Saarbrücken branch had been expanded significantly with the addition of the County of Saarwerden, a few miles upriver on the Saar, in the Vosges mountains. A werd was a small island in German, and this county was built up in the twelfth century around the towns of Saarwerden (presumably in the river at the time) and Bockenheim on a nearby bank. Like Saarbrücken, it was initially a fief of the bishops of Metz, then independent for several centuries. The most famous member of its first dynasty was Friedrich, Archbishop of Cologne, 1370-1414. By the time of his death, the county had passed by marriage to the counts of Moers (whose lands were much further north, in the lower Rhine near Cologne). In the 1550s, Lutheranism was introduced here, despite the fierce opposition of the neighbouring prince, the Duke of Lorraine—it became a place of refuge for Huguenots fleeing persecution in France, so for a time had both a Lutheran and a Calvinist church existing peaceably side by side. In the 1570s, the counts started also to introduce the reform in Saarbrücken as well, so the Duke of Lorraine struck back and claimed both counties, pursuing the House of Nassau in the Imperial courts. The progress of this lawsuit is another excellent example, as with Katzenelnbogen above, of the incredible slowness of justice within the Holy Roman Empire, and due to this, and of course the intervening turmoil of the Thirty Years War, nothing was resolved until the Treaties of Westphalia, 1648, which restored both Saarbrücken and Saarwerden to the House of Nassau—though as a security, the Duke of Lorraine retained control over the two towns of Saarwerden and Bockenheim (now Frenchified as Sarreverden and Bouquenom). The Count had to move across the river and built a new capital, Neu-Saarwerden, though not until 1702. There was never a grand princely residence in Saarwerden (it was a very remote place), but the new schloss did reflect the ethos of the time, built along the sober and organised ideas of the Enlightenment (and has sometimes between called ‘the Mannheim of the Nassau’, referring to the idealised planned city on the Rhine, built about the same time). After Lorraine was annexed to France in 1766, Sarrewerden remained a Protestant enclave in Catholic France (and with Catholic Bouquenom as an enclave within an enclave at its centre). In 1793 it was annexed to the French Republic, and the two towns were united with a new name, Sarre-Union, which they still retain today.

A more interesting residence was built by this branch at Ottweiler, in the eastern part of the County of Saarbrücken. It had an old fortification from the twelfth century, a gothic schloss from the fourteenth, then rebuilt in Renaissance style in 1550, with four wings and open galleries. When the Weilburg and Saarbrücken branches were merged after 1574, the Weilburg branch temporarily made this their chief residence. When the lines were split again in 1640, Nassau-Ottweiler became its own entity. But damaged in the Thirty Years War, its castle was neglected and later demolished in 1753. The town was developed by later princes of Nassau-Saarbrücken as a centre of porcelain manufacture (from the 1760s).

Of the later sixteenth-century Nassauers, Count Albrecht of Saarbrücken was most prominent, as brother-in-law of William of Orange and a supporter in his armed struggle against the Duke of Alba in the Low Countries in 1568. By 1605, Albrecht’s son Count Ludwig II re-combined all of the Walramian branches—Wiesbaden-Idstein, Weilburg and Saarbrücken—and moved his seat more permanently to Saarbrücken. Here he built a school like that in Weilburg, the Ludwig Gymnasium, and sponsored projects that would make the river Saar more navigable. When he died in 1627, the lands were divided once again, with lands west of the Rhine going to the eldest, Wilhelm Ludwig, and lands east of the Rhine going to Johann (Idstein and Wiesbaden) and Ernst Kasimir (Weilburg). These three brothers joined the Protestant side against the Emperor in the Thirty Years War (first fighting alongside the King of Sweden, then aligning themselves with France), and thus had much of their lands confiscated. Even when many Protestant German lands were restored by treaty in 1635, the Nassau counts were deliberately excluded, and they had to wait until the Treaties of Westphalia in 1648—by which time many of their towns and castles were ruined, their populations decimated.

The senior line, in Saarbrücken, split again into three: Ottweiler, Saarbrücken, and a new division, Usingen. Of these counts, the most prominent was Count Gustav Adolf of Saarbrucken (clearly named for the Swedish king), who, although he had served in the French army in his youth, clashed with Louis XIV’s ‘reunion’ strategies as an older man in the 1670s. The French king directed his army of lawyers to find obscure feudal laws with which to claim territories that should be ‘re-united’ with France. In particular, since France now ruled over Metz, the former fiefs of Metz should be French too—this included Saarbrücken and Saarwerden, and both territories were occupied. Gustav Adolf’s son Count Ludwig Crato fought against this and served in the armies of the Dutch Republic against France, until his lands were restored by the Treaty of Ryswick, 1697. He continued to develop Saarbrücken into a fine baroque capital, as seen above. He also built a country retreat, a lustschloss called Monplaisir, in Halberg, east of the town, complete with a baroque garden, to which later princes added a zoo, an English garden and a Chinese pavilion. All of this was destroyed by the French in 1793 (a new and completely different castle was built at Halberg in the 1880s). Ludwig Crato’s brother, Count Karl, continued to develop the county’s economy, adding glass and salt industries that laid the foundations that established this region as a leader in the Industrial Revolution.

Meanwhile, the line of Wiesbaden-Idstein was led by Count Georg August, who served at the Siege of Vienna in 1683 and was one of several counts of the House of Nassau to be elevated in rank to become a Prince of the Empire, in 1688. Several of the branches of the Ottonian branch had been so created in the 1650s (Dillenburg, Hadamar, Dietz, Siegen), which much have irked those of the Walramian line considering that they were technically the senior branch. Also elevated to the rank of fürst in 1688 were the counts of Weilburg and Usingen, though why not Ottweiler or Saarbrücken, I am not certain—perhaps because they were occupied by France at the time. As imperial princes, the Nassau lords now had a vote in the Imperial Diet, not just one of the collective votes held by the counts of the Wetterau.

Georg August commemorated his new status by building a Herrengarten in Wiesbaden, and moving his residence from the old schloss at Idstein, to a brand new palace right on the banks of the Rhine, Biebrich. This was a residence fit for princes and remains one of the finest examples of Rhineland baroque architecture. Work began in 1702 and was completed in 1721; it included two pavilions connected by a long gallery and a circular ballroom at the centre. Two wings were added by later princes in the 1730s. Biebrich Palace was damaged in World War II, and mostly rebuilt in the 1980s. Today it is used by the state of Hesse for ceremonies and to house heritage offices.

When Georg August died in 1721, his lands passed to the Ottweiler line, as did those of Saarbrücken when Count Karl died in 1723. The Ottweiler line itself went extinct in 1728, meaning all these lands (except Weilburg, see below) passed to the new branch, Nassau-Usingen.

Usingen was a small town in the High Taunus mountains, east of Weilburg, on the Usa river. It had been acquired by the Nassau family in 1326 who built a small castle, but otherwise left it alone. In the 1660s, Count Walrad carved out a new territory here and built a new residence. He served as a Field Marshal in the army of the Emperor and later for the Dutch Republic. He too served at the Siege of Vienna and then in the campaigns in Hungary, for which he too was rewarded by being created Prince of Nassau-Usingen in 1688. After a fire of 1692 destroyed much of his town, he rebuilt it—like Neu-Saarwerden, according to the ideals of the early Enlightenment, and he settled it with Huguenot refugees (and unlike some of his Lutheran cousins, he himself was a Calvinist). The princely residence was remodelled in the 1730s—destroyed in 1873, it was rebuilt in a quite sober style, and is now a school. There was also the ‘Prince’s Palace’, built in the centre of town in the 1770s, but sold in the early nineteenth century—it has housed local administrative offices ever since.

Prince Walrad died in service of the Emperor early in the War of Spanish Succession in 1702. His son Wilhelm Heinrich, 2nd Prince of Nassau-Usingen, once again reconnected the two main branches of the House of Nassau by his marriage in 1706 to Princess Charlotte Amalia of Nassau-Dillenburg. Wounded in the service of the Dutch army in 1703, he left military service and died relatively young in 1718. The 3rd Prince, Karl, was thus the cousin who gathered back together all the properties of Wiesbaden, Idstein and Saarbrücken in 1728, and moved into the fine new palace at Biebrich, where he lived a long and mostly peaceful life until 1775. He left two sons, soldiers, and a bastard, Karl Philipp, whose mother had been created Baroness von Biebrich in 1744, and who himself would be called the Count of Weilnau. This name came from a medieval county next door to Nassau, like Weilburg built above the river Weil, that was absorbed by the Nassau counts in the 1330s. Weilnau still has remains of an old castle and a new castle from the sixteenth century.

In 1735, Prince Karl of Nassau-Usingen gave the counties of Saarbrücken and Saarwerden to his brother Wilhelm Heinrich II, who was created a fürst as well, finally bringing the Saarbrücken branch in line with the others. The 1st Prince of Nassau-Saarbrücken ruled one of the smallest principalities in the Empire, at only 12 square miles and with only about 20,000 people. Nevertheless, it had one of the finest capitals, with a new grand baroque princely palace, as we’ve seen, and a burgeoning industrial economy, with Saarland coal and iron. Wilhelm Heinrich led a regiment of Nassauers in the service of King Louis XV of France, in the War of the Austrian Succession and the Seven Years War, and was ultimately promoted to the rank of lieutenant-general. Back in Saarbrücken he constructed a new hunting lodge, Jägersberg—but ultimately all his projects left his principality in debt.

He was succeeded in 1768 by his son, Ludwig, 2nd Prince of Nassau-Saarbrücken who continued to develop this principality as an ‘enlightened absolutist’, building schools, developing agriculture, reforming the penal code. He too built a new palace, Ludwigsberg, in 1769, and a new state church, Ludwigskirche, 1775. Though he was a learned and determined reformer, that was not enough for the French revolutionaries who swept into the Rhineland in 1793, and he fled in May, dying the next year near Frankfurt. He left a son, Heinrich Ludwig, the 3rd Prince, who joined the Prussian army in 1793, but died in 1797, having never reigned in his occupied principality. Neither Ludwigsberg nor Jägersberg survived the revolutionary era.

There was now only one male left of this line of Nassau-Saarbrücken, Adolf Ludwig, who had been born of the 2nd Prince’s second morganatic marriage so was not entitled to the rank of prince. His father had ensured that his mother, a former maid of one of his mistresses, had been created Countess of Ottweiler (1784), so the son also took this title. There are suggestions (but I’ve not seen any verification, and it sounds unlikely to me) that Prince Ludwig persuaded King Louis XVI to create his wife Duchesse de Dillange (aka Dillingen, in Saarbrücken), in the Spring of 1789, and that Adolf Ludwig was later called the Duc de Dillange. He did (as Count of Ottweiler) join the army of the King of Württemberg, then volunteered in Napoleon’s campaign in Russia in 1812, where he died.

Back in Usingen, the 3rd Prince had been succeeded in 1775 by his eldest son, Karl Wilhelm, who added took the title 4th Prince of Nassau-Saarbrücken in 1797. He had served as a lieutenant-general in the Dutch army in the 1770s, and in 1783 was one of the signatories of the mutual succession pact for all of the branches of the House of Nassau (including Orange-Nassau, which was ultimately important to the history of Luxembourg, as we’ve seen). In the commission that dismantled the Holy Roman Empire in 1803, he was compensated for lands lost west of the Rhine (Saarbrücken and Saarwerden) with lands taken (mostly) from secularised archbishoprics of Mainz and Trier, but also from Hesse and the Palatinate. He died that same year, passing his lands and titles to his brother, Friedrich August, now 5th Prince of Usingen, an Imperial Field Marshal since 1790, who joined the Confederation of the Rhine in July 1806, and formed the new Duchy of Nassau with his Weilburg cousin in August—they agreed to a joint rule (with Friedrich August taking the senior title of Duke) since Usingen had no son. This was approved by the Congress of Vienna in 1815, and the 1st Duke of Nassau died in March 1816.

So finally, we need to focus again on the line of Nassau-Weilburg itself, and bring this story to a close. The youngest son of Count Ludwig II, Ernst Casimir, did not spend much time in his portion of the County of Nassau, as imperial troops drove him and the rest of his family out of the area during the Thirty Years War, and he died shortly after these lands were restored. It was his grandson, Count Johann Ernst, who brought this branch of the family back to prominence, and was, like the other heads of branches, created 1st Prince of Nassau-Weilburg in 1688. He served as a general in the army of the Elector Palatine, and later as an Imperial Field Marshal defending the Rhine against a French invasion in the War of Spanish Succession. He was also the Grand Master of the Court for the Elector Palatine in Düsseldorf until 1716, rebuilt his own smaller court residence in Weilburg, and died a few years later in 1719.

His son, Karl August, 2nd Prince of Nassau-Weilburg, had already been active as a diplomat in service of the Elector of Saxony (who was also the King of Poland). As a prince he was a cavalry general in the Imperial army in the 1730s. The 3rd Prince, Karl Christian, took over in 1753, and a few years later raised the dynastic profile of his branch of the family through marriage to Princess Carolina of Orange-Nassau, daughter of William IV, Prince of Orange, and Princess Anne of Great Britain, the eldest daughter of King George II. His connections with the Netherlands allowed him to rise in the military and by the 1770s he was a general in the Dutch Army and governor of the City of Maastricht.

The 3rd Prince died in 1788, leaving his principality to his son Friedrich Wilhelm, the 4th Prince, who agreed in 1815 to act as the junior partner in the joint rule of the new Duchy of Nassau, on the assumption that he would succeed the senior partner (Friedrich August of Usingen, as above), but he died three months too soon (in January 1816), so it was his son Wilhelm who became 2nd Duke of Nassau, the newly unified state within the German Confederation, pulling together all of the territories of the Walramian branches of the House of Nassau east of the Rhine (Wiesbaden, Idstein, Weilburg, Usingen), and some of the lands of the Ottonian branches (Dietz, Hadamar)—but not those further north like Siegen, which were given by the new King of the Netherlands (Orange-Nassau) to the King of Prussia by the Congress of Vienna in exchange for the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg.

Duke Wilhelm married well, to Louise of Saxe-Hildburghausen, niece of Queen Louise of Prussia and Frederica, Duchess of Cumberland (later Queen of Hanover), and grand-niece of Queen Charlotte of Great Britain. His sister Henrietta connected the family to the Catholic houses of Europe by marriage to Archduke Karl of Austria, younger brother of Emperor Francis I and commander-in-chief of Austria’s armies. Intriguingly, Archduchess Henrietta did not have to convert to Catholicism herself, though her children had to be raised in the faith, and she left behind her ‘surname’ on the landscape of Austria, in the Weilburg Palace in Baden, a spa town south of Vienna—sadly destroyed by fire in April 1945.

Duke Wilhelm was succeeded by his eldest son Adolf as 3rd Duke of Nassau in 1839. It was he who made Wiesbaden formally his capital and rebuilt the Stadtschloss there as his chief residence. Although he was a liberal ruler, his rule was threatened by the revolts of 1848 that shook all the thrones of Europe, and in the aftermath he became much more conservative. In an effort to support the old ways of Germany, under the guidance of the ancient Habsburg dynasty, he supported Austria in its short war against Prussia in 1866, and paid the price. Nassau was annexed to Prussia, and its Duke had to wander around the courts of Europe for a few years before settling into a new residence, Schloss Hohenburg in Bavaria. Built in the 1710s by Count von Herwarth, then sold to various people including the Prince of Leiningen (Queen Victoria’s half brother), Duke Adolf purchased it in 1870 from Baron von Eichthal. Twenty years later, already in his seventies, he succeeded to the Grand Ducal throne in Luxembourg, as seen towards the start of this post, by virtue to the Nassau Family Pact of 1783. He kept Hohenburg as a summer residence, and it later became the residence of Grand Duchess Marie Anne of Portugal, widow of Grand Duke William IV. She left Germany at the start of the Second World War and died before it ended. The castle was sold in 1953 to create a convent school.

As with the previous generation, the sisters of Grand Duke Adolf (or Adolphe in French) helped link this new royal house to other reigning houses in Europe: Princess Helene became the mother of Emma, Queen of the Netherlands, while Princess Sophia had already become Queen of Sweden and Norway, since 1872. Adolf’s fifteen-year reign set the standard for limited direct involvement in the Grand Duchy’s government. He died in 1905 and was succeeded by his son William IV, who, as seen above, died only a few years later in 1912 with no male heirs. One faint claim was made, from Georg, Count von Merenberg, who protested that his father Prince Nikolaus’ morganatic marriage did not necessarily block him from the succession to the throne of Luxembourg. Wilhelm IV ruled that it did in 1907, and the throne passed smoothly to his daughter Princess Marie-Adélaïde.

Prince Nikolaus of Nassau (who had died in 1905), was a Prussian general (so, no hard feelings about the annexation of his brother’s duchy then). In 1868, he married Natalia Pushkina, daughter of the famous Russian poet. Despite a very illustrious ancestry—very ancient Pushkins, Rurikovichi princes, and, more exotically, Abram Gannibal, Peter the Great’s famed African general, and Petro Doroshenko, a Cossack general—she was not deemed of sufficient rank to marry a prince, so the marriage was deemed morganatic, and she was created Countess of Merenberg—taking this title from another one of the old medieval counties absorbed by the counts of Nassau back in the fourteenth century, not far from Weilburg. The line of the counts of Merenberg continued into the twentieth century, with close connections to the Romanovs and later to the Mountbattens. When the last of these, Count Georg Michael, died in 1965, he was the last male member of the entire House of Nassau—he left one daughter, Clotilde, who is still living, the last scion of an ancient dynasty.

Since 1964, the merger of the houses of Nassau-Weilburg and Bourbon-Parma has generated a hybrid Franco-German dynasty that suits this small state at the crossroads of cultures. Luxembourg’s daily newspapers are printed in French, German and Luxembourgish, and the sons and daughters of its ruling dynasty have married spouses from across the region, for example the new Grand Duke Guillaume’s consort, Stéphanie, who comes from a noble Belgian family, the House of Lannoy (which has in the past included some princely titles, so deserves its own blog post), and others from more far flung places, such as Grand Duchess Maria Teresa, born in Cuba.

(images Wikimedia Commons)

brilliant.

was the prince of Nassau saarbrucken who was A CHEVALIER DU SAINT ESPRIT a protestant?

this dynasty handled its situation in 1918/9 better than the Hohenzolleerns and other German dynasties, which had no members not compromised by the 1914-18 war.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, he was a Calvinist. I saw something about Louis XV giving dispensations to him and other commanders of German regiments…I’ll try to locate it again.

LikeLike

This needs to be explored further–he does not appear on lists of the Order of the Saint-Esprit. There are other portraits of him in a different uniform with a different order.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I thought the prince regent was the first no catholic saint esprit at least since 1610

>

LikeLiked by 1 person

Princess Irene of the Netherlands married in 1964, not in 1965.

After their expulsion from Spain, Irene and her husband Prince Carlos Hugo moved to France, not to The Netherlands – though their children were indeed born in Dutch hospitals.

Carlos Hugo was for a while seen as contender for the vacant Spanish throne, played by dictator Franco against Prince Juan Carlos. After the restoration of the monarchy in 1975 and a non successful attempt to enter parliament, Carlos Hugo stopped his efforts, but did not pass them to his younger brother Sixte.

Sixte himself promoted himself, in opposition to his brother and now to his brother’s successor, Prince Carlos. The Luxembourg family recognises Carlos as the current head of the Bourbon Parma family; he is also recognised in the ancient duchies, where he attends civic and dynastic events yearly.

Prince Carlos and his siblings obviously were members of the Dutch royal family by birth; in 1996 they were admitted to the Dutch nobility, which is something else altogether.

Interestingly you mention the mother of Dutch Queen Emma, the last (non reigning) Grand Duchess of Luxembourg from the House of Orange-Nassau. Because of the Saluc succession law in Luxembourg her daughter Wilhelmina could not succeed in the Grand Duchy. Emma squashed any attempts to change that, partly because her own family’s connection to the Nassau-Weilburg branch. Only to see them change the succession laws when Wilhelm IV only had daughters…

Final remark: how is Maria Teresa a dowager Grand Duchess? Did her husband die?

LikeLike

thank you so much for these points of clarification. Always a danger for a 17th-century historian straying into 21st-century topics! You’re completely right to point out the error about the ‘Dowager’–just a a typo as I was finishing off the post late in the evening! 🙂

LikeLike

Your comment about the current relationship between the Bourbon-Parma family and the city of Parma itself made me remember my own experience visiting the city two years ago, and how surprised I was that the entire history of the Bourbons being in Parma has almost entirely been wiped away by current tourism–everything is either about the Farnese or Empress Marie-Louise. A shame, really.

LikeLike