One of the least known dukedoms in the peerages of Great Britain is that of Cleveland. After starting off as a title for one of the most famous duchesses in Europe, Barbara Villiers, the second and third dukes, Charles and William FitzRoy, were very rich but unremarkable. Their successors in the Vane family managed to revive the dukedom in the nineteenth century, and although they maintained one of the greatest estates in England, Raby in County Durham, they too did little to make themselves memorable in the history of the British aristocracy and left little trace when they died out in 1891.

As with many of the great houses of Europe, much of the fame, and the reason for their elevation to the most exalted title, came from whom they descended: in the case of the first dukes, they were the son and grandson of the King of England, Charles II. For the Vanes, the illustrious ancestors were a bit further back, leaders of the Parliamentary party of the seventeenth century, and solid members of the subsequent Whig Party in the eighteenth. So it is interesting to pair them together considering the first were naturally supporters of the Crown, while the latter did much to limit its power. The Vanes are also a good example of the enduring power of a county family in Britain, as one of the largest landowners in County Durham and lords lieutenant there off and on for over two centuries (1753 to 1988).

Where is Cleveland? Aside from the US city in Ohio (named for General Moses Cleaveland), and the ‘Cleveland Street Scandal’ of 1889 (for afficionados of Victorian London), which took place in Fitzrovia, once part of the 2nd Duke of Cleveland’s estate, the name does not conjure up a specific place. But there is a Cleveland, named for the cliffs that overlook the North Sea in the area just south of the mouth of the River Tees and north of the North York Moors. There was once a County of Cleveland, from 1974 to 1996, with its county town of Middlesbrough. Most of the area is in Yorkshire, but part of the short-lived county was across the Tees in Durham, which is more connected historically to the title of the dukedom that bears its name.

The first bearer of the title was not a duke but a duchess: Barbara Palmer, née Villiers, the most influential of all of Charles II’s mistresses, who was Lady Castlemaine (an Irish title) by marriage, then was elevated to the peerage on her own in 1670 as Baroness Nonsuch, Countess of Southampton and Duchess of Cleveland. She was given Nonsuch Palace, in Surrey, which she had torn down in the 1680s to cover her great debts. Her story is more fully told in the blog about the dukes of Buckingham and the rest of the Villiers family. The letters patent for the duchy specified that it was created for Barbara, and not her husband, and her eldest son by the King, Charles FitzRoy, born in 1662.

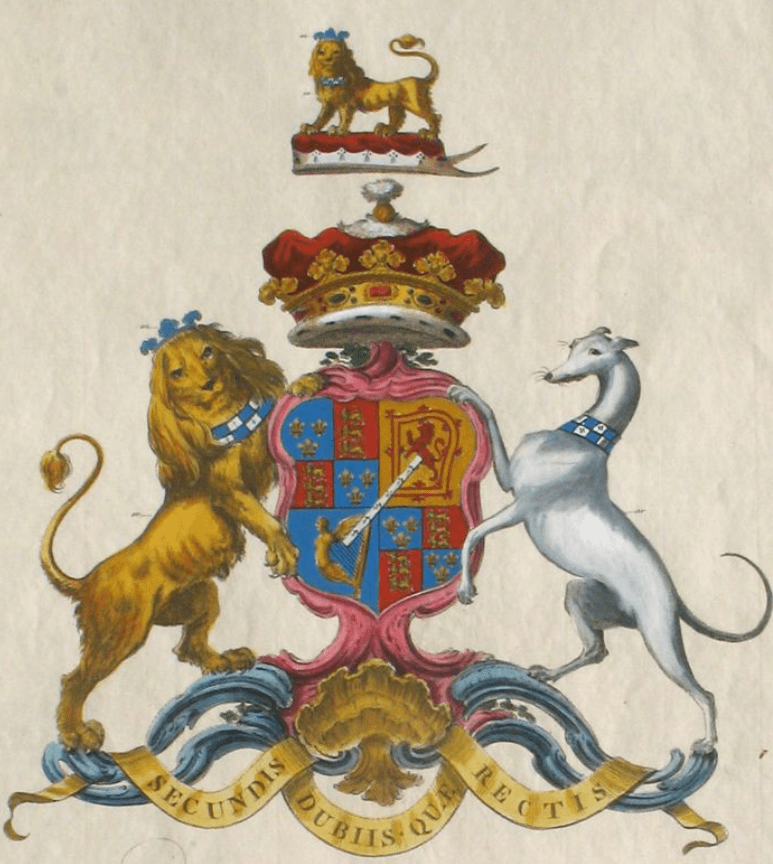

At first, the boy, Lady Castlemaine’s second child with the King, was formally recognised by her husband, and baptised a Catholic as Charles Palmer, Lord Limerick (the Castlemaine courtesy title); but only a few days later the King insisted on another Protestant baptism, and the name FitzRoy (‘son of the king’), though this wasn’t formally acknowledged until the creation of the titles in 1670 when the boy was eight. By this point he had two brothers, Henry FitzRoy, soon to be created Earl of Euston then Duke of Grafton; and George FitzRoy, Earl of Northumberland (later also a dukedom). While Henry was soon well set up with the succession of his wife (the Euston estate), and his heirs continue today, George and his potential heirs were named in the remainder for the dukedom of Cleveland after his oldest brother, but did not have any heirs. All three boys were given the coat of arms of the royal Stuarts with a band sinister denoting illegitimacy: a simple band of ermine (a fur symbolising princely rank) for the eldest, a band of silver and blue for Henry and ermine and blue for George. Some of their estate was developed into an urban district north of the City of Westminster and named ‘Fitzrovia’. Most of the subsequent FitzRoy story will be told in a post about the dukes of Grafton.

In 1675, Charles was given a peerage of his own: Duke of Southampton, with subsidiary titles Earl of Chichester and Baron Newbury. The Southampton title, an elevation of his mother’s earldom from 1670, had been an earldom before, notably for the Wriothesley family who rose to such prominence in the Tudor era after the fall of Thomas Cromwell (as depicted so well in the novels by Hilary Mantel). The 4th Earl was also 2nd Earl of Chichester (which he inherited from his father-in-law, Francis Leigh), so these titles were already linked when that family went extinct in 1667. Different heiresses took the Wriothesley estates into the Russell and Montagu families (both who grew rich by developing the Bloomsbury estate in London, notably abutting Fitzrovia). Perhaps the King hoped to pick up one of these heiresses to establish his son, as he would do for several of the others (and named Henry ‘earl of Euston’ in anticipation, even before he was engaged). I don’t know why Baron Newbury was chosen—it doesn’t have a history of being a title, and is mostly known as a market town in Berkshire where two significant battles had been fought in the English Civil War (I thought for a moment it might have been named for the King’s favourite country hangout spot, the races, but that’s Newmarket, not Newbury).

In any case, by 1670, Charles FitzRoy was betrothed to Mary Wood, whose family was not eminent, but whose father, Sir Henry Wood, Bt., was a lifelong supporter of the Stuart dynasty and a very rich man. Wood had been Treasurer of the Household of Queen Henrietta Maria, then Clerk of Green Cloth, and he had estates in Suffolk (notably at Ufford, near the coast, and the lands of the former Priory of Campsey), as well as estates closer to London such as Clapton in Hackney Downs in Middlesex. When Henry Wood died, his family, notably brother Thomas, Bishop of Lichfield, tried to take Mary into custody, but Barbara basically kidnapped her, to raise her as her future daughter-in-law. The children were married in 1679, but the new Duchess of Southampton died in 1680, still only seventeen.

The Wood family challenged the Duke of Southampton’s claims to his late wife’s inheritance, and lost. So by 1692, the Duke could establish himself in a country seat in Suffolk, at Loudham Hall. This was an old manor house owned by the de Loudham family from the 1200s, rebuilt in the sixteenth century by the Blannerhasset family, then sold in 1627 to Henry Wood, who enlarged the house. After the Duke of Southampton’s death in 1730, the Wood succession did not pass to his son by a second marriage, but back to the Wood family, who refaced Loudham in Classical style, then sold it in 1792 to the Whitbread family, known for their beer, who owned it until 1919. It was held by the Adeane family for much of the twentieth century, but has since been sold several times and remains private. It was recently in the hands of Mike Lynch, technology entrepreneur whose name was in the papers due to a trial for fraud in the UK in 2019 and in the US in 2023, of which he was acquitted, then his sudden death in a boat accident in the Mediterranean in August 2024 (within a day of his co-defendant, hit by a car while jogging).

Meanwhile, the Duke was married again, in 1694, to another potential heiress, Anne Pulteney, whose family were minor landowners in Leicestershire. At the time, Anne was not an heiress, with two older brothers who produced heirs, but the Pulteney Estate succession will come up again later, with significant lands in Somerset and in Shropshire.

In 1709, the 1st Duke of Southampton became the 2nd Duke of Cleveland when his mother died. In 1720, he bought a London townhouse on St. James’s Square—the most fashionable address in London (ultimately housing seven dukes). Built for the Earl of Essex in 1674, this was not the house a few streets away known as Cleveland House, where his mother lived from 1670—that was an older house built by the Howard family in the 1620s, and since the eighteenth century known as Bridgewater House (behind Clarence House and overlooking Green Park). This new Cleveland House was located on the west side of St. James’s Square, No. 19, though in the nineteenth century, its main entrance was re-orientated and became No. 33 King Street. It was completely demolished in 1895 and rebuilt as offices and flats, and again in 1999 (today it notably houses the Rolex headquarters).

As for the Duke himself, Charles FitzRoy left very little tales of political or social life. Though he ranked high, as third English duke in precedence (behind Norfolk and Somerset), he rarely sat in the House of Lords and was considered by many to be ‘not very bright’. He didn’t need to get involved in financial schemes, since his income was already valued around £100,000 a year. At court he inherited the office of Chief Butler of the Household from his brother the Duke of Northumberland in 1716. This at least could have brought him some prominence in his chief duty of organising and hosting the coronation banquet, but more research needs to be done to see what if any tasks he undertook in this guise for the coronation of George II in 1727. He died in 1730.

Charles and Anne had six children: Lady Grace, who will link the FitzRoys to the Vanes; then three sons, William, Charles and Henry. William succeeded as 2nd Duke of Southampton and 3rd Duke of Cleveland in 1730. Lord Charles had died in 1723 aged 25, and Lord Henry in 1709, only 8. There were also two sisters, Lady Barbara—finally, some recognition for the former Barbara Palmer!—who did not marry; and Lady Anne, who married John Paddey, Esq., a member of London’s judiciary set (who is sometimes listed as ‘Francis Paddy’, as he appears in some of the printed peerages of the era).

Like his father, William, the 3rd Duke of Cleveland and 2nd Duke of Southampton, was said to be ‘not very bright’, and also rarely sat in the House of Lords, spending most of his time, it seems, at the races. Known as the Earl of Chichester as heir, he was rarely seen at court either. Lord William did inherit his father’s court office of Chief Butler, and again it would be interesting to see what role exactly he performed at the coronation of George III in 1760. The Duke was given some political offices, but these were mainly to generate an income and had really interesting names, like Comptroller of the Seal and Green Wax Offices. In 1731, he married Lady Henrietta Finch, daughter of Daniel, 2nd Earl of Nottingham and 7th Earl of Winchilsea, a prominent Tory politician in the late seventeenth century, now long retired—so if anything, the Duke of Cleveland supported Tory interests (and he was noted as an ‘opponent’ to the ministry of the Whig Duke of Newcastle in the early 1760s). Henrietta was not an heiress at all, as sixth daughter, but her brother’s political career does link this story again to the Pulteney family, as an ally of the Earl of Bath.

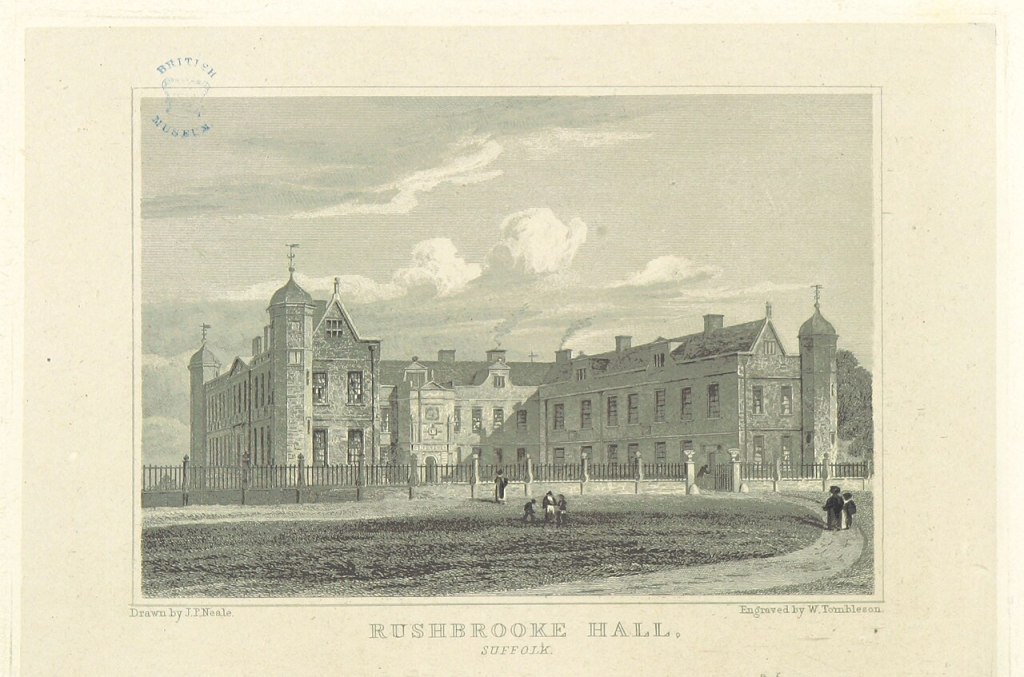

The Duke did not inherit the Wood estate, notably Loudham Hall, and he is noted as early as the 1740s as spending much of his time at his brother-in-law’s estate, Raby Castle, in County Durham. He lived at Cleveland House when in London, and rented out houses in the countryside for short periods. A printed peerage from 1766 lists his residences as ‘Bayles, near Windsor’ (Baylis House in Berkshire, owned by the Osborne family, dukes of Leeds), and ‘Combe-park, Surrey’ (probably Coombe House, near Croydon). Further afield, we see that he rented Rushbrooke Hall, but only for a few years in the 1760s. Like Loudham, Rushbrooke is located in Suffolk, but on the western side of the county, closer to Bury St Edmunds. This moated manor house had been in the Jermyn family since the 1230s. The 2nd Baron Jermyn died in 1703 and his daughter took the house by marriage into the Davers family (baronets) who rented it out to the Duke of Cleveland, but only for a few years in the 1760s. In the nineteenth century, Rushbrooke was rented out to a family of that name. By the mid-twentieth century it fell into disrepair and was demolished.

Towards the end of his life, the Duke of Cleveland and Southampton was living full time at his nephew’s estate, Raby Castle, where he died in 1774. His titles all went extinct. There was never again a dukedom or even earldom of Southampton—though a few years later, in 1780, a younger son of the Duke of Grafton, another Charles FitzRoy, was created Baron Southampton, a title that continues today.

And so, on to the Vanes and Raby Castle!

The Vane family were originally from Kent, from the area of the upper Medway valley near Tonbridge. They are part of a wider family who spelled their name either Vane or Fane. One branch, the Fanes of Badsell, became earls of Westmorland in 1626, and also inherited the ancient baronies of Bergavenny (from the Nevilles) and Le Despencer. Their seats were Mereworth Castle in Kent and Apethorpe Hall in Northamptonshire. This line continues to the present with the 16th Earl, Anthony Fane, born in 1951. The ancestor that links these to the Vane family of Cleveland is Sir John Fane, or Ivon Vane, whose name suggests he was from Wales. He made his fortune by capturing King Jean II of France on the battlefield at Poitiers, 1356, and received a large ransom for him. Later genealogists, however, say the common ancestor is the less exciting Henry Vane from Tonbridge in Kent who died a century later. Regardless, both branches of the family bear a golden gauntlet on their coat-of-arms referring back to the Ivon Vane story. They differ in that the Fanes show the back side of the gauntlet and the Vanes use the palm side.

Sir Henry Vane the Elder came from out relative obscurity in the reign of Charles I to become one of the richest men in England. He had served in the King’s household from the time he was Prince of Wales, and became one of the King’s closest financial advisors in the 1630s—rising to Treasurer of the Household in 1639, and Secretary of State in 1640. He sold his ancestral home of Hadlow, Kent, and purchased Fairlawne in Kent, and the huge estates of Barnard Castle, Raby Castle and Long Newton, all in the County of Durham, in the far north of England. Here he was appointed Warden of the Teesside Forests. In May 1641, Vane got caught up in the King’s dismissal and execution of the Earl of Strafford, and was himself dismissed from office. He defected to the Parliamentarian side to oppose royal tyranny and was appointed by them to the post of Lord Lieutenant of Durham—the first of many of his line to hold this position. He died in 1655, a very large landowner.

In Kent, Fairlawne was a large manor in Shipbourne near Tonbridge. Sir Henry the Elder had the house rebuilt in the 1630s, and it was upgraded again in the 1720s. It was given to a younger branch (viscounts Vane) in the eighteenth century, then passed to another family after 1789. Many Vanes are buried in the local church of St Giles’. The Cazalet family, wealthy merchants, took over as lords of the manor in the 1870s, and today it is owned by a Saudi prince. It is still a large estate, with over 1000 acres.

Up in County Durham, Barnard Castle is a Norman castle built to watch over the river Tees as it passes through a gap of the eastern foothills of the Pennines on its way down towards the larger towns of Darlington and Stockton. For centuries the river was the border between Yorkshire and the County Palatine of Durham, so called as its bishop enjoyed ‘palatine’ (or ‘palace-like’) powers, for practical reasons since this area was so far from London. Being so far north, its noble families usually had some connections to Scotland as well, and the family who owned the castle from the eleventh to the thirteenth centuries were the Balliols, who even claimed the Scottish throne briefly in the 1290s. Guy de Balliol built the first castle here in about 1095 to protect the first Norman bishop of Durham. His nephew and successor Bernard gave the castle its name. Once the Balliols became too caught up in the Scottish Wars of Independence against King Edward I, the Bishop of Durham confiscated Barnard Castle; a few years later the King granted it to the Earl of Warwick, whose descendant Anne Neville married Richard, Duke of Gloucester, who made the castle one of his preferred seats in the North. He of course became King Richard III and the estate was merged with the Crown until it was sold to Sir Henry Vane. Vane used much of the stone and roof of the already crumbling Barnard Castle to fix up nearby Raby, and it remains a ruin, today in the care of English Heritage. It is still an impressive fortress, and a fun visit alongside the nearby market town of the same name—made famous in the British media in May 2020 by the rather strange drive by Dominic Cummings to ‘check his eyesight’ during lockdown.

It was Raby Castle, a few miles to the northeast, that became the real jewel in the Vane family crown. The castle today is a major attraction in Teesdale and the large estate includes the High Force Waterfall further up the Tees in the North Pennines. The moated castle was built in the 1370s by John Neville, 3rd Baron Neville of Raby, whose family had owned the site since the thirteenth century, and were called to Parliament as barons of Raby from 1295. The Neville family is one of England’s greatest aristocratic clans, and will receive their own blog post, though they only held a dukedom (Bedford) briefly in the 1470s. John Neville’s son Ralph was created Earl of Westmorland in 1397 and the family held this title until 1571 (after which, as we’ve seen, it passed to the Fane family). There is a link here in that the uppermost reaches of the river Tees forms the boundary between County Durham and County Westmorland. Junior branches of the House of Neville became earls of Salisbury and earls of Warwick, leading to Anne, queen-consort of Richard III as we’ve seen; but there was another Neville queen, Cecile Neville of Raby, daughter of the 1st Earl of Westmorland, who married the Duke of York and was mother to both Edward IV and Richard III. Raby Castle remained the Neville seat throughout the Wars of the Roses and the early Tudor period. In 1569, the 6th Earl took part in the Northern Rising in support of Mary, Queen of Scots’ claim to the English throne, and Elizabeth I confiscated his lands and titles. The Crown now held Raby Castle until it was sold to Sir Henry Vane in 1626. It has stayed in this family ever since. Since the 1960s it has been spruced up and opened to the public, and is also often used for television and film crews, for example in 1998’s blockbuster Elizabeth.

The third property purchased by Henry Vane in County Durham was Long Newton, a manor located on the road between Darlington and Stockton. It passed to his younger son, Sir George Vane, who started a separate line that was equally prominent in its own way: Vane-Tempest. The baronetcy of Vane of Long Newton was created in 1782, due to the merger of this family with the Tempests of nearby Wynyard Hall. The Vane-Tempest family made its fortune from shipping coal, which then passed via marriage to the Stewart family of County Down in Ireland. These became the Vane-Tempest-Stewarts, who bore the titles Marquess of Londonderry (1796, peerage of Ireland), and Earl Vane (1823, UK peerage), and continue to the present. The current Marquis of Londonderry, the 10th (Frederick Vane-Temple-Stewart), was born in 1972; his heir is Viscount Castlereagh of County Down.

The senior branch of the House of Vane, of Raby, was founded by Sir Henry the Elder’s son, Sir Henry, the Younger. His father tried to promote his career at court in the 1630s, but the younger Henry was more passionate about his Puritan beliefs and left for the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1635. A year later he was elected governor of that colony, but only served one year, poorly handling both religious controversy in the colony and military action against the nearby Pequot tribe. He returned to England and championed the Parliamentarian cause against the Crown far more than his father, and during the Commonwealth he served on the Council of State, 1649-53 (and briefly as its president, May to June 1652). In the Restoration he was initially granted clemency by Charles II, but was nevertheless condemned by a government commission and executed in June 1662.

Henry Vane’s son Christopher continued to support the Parliamentary cause, which morphed into the Whig Party by the 1670s. As a supporter of the reign of William and Mary, he was named to the Privy Council, 1688, and later elevated to the peerage by King William in 1698 as Baron Barnard of Barnard Castle. He married Elizabeth Holles, which tied him to one of the premier Whig families (her brother was created Duke of Newcastle in 1694; and her two Pelham nephews would both be Whig prime ministers in the eighteenth century).

Christopher and Elizabeth had three sons. The youngest, William, another Whig politician, was created Viscount Vane in 1720 (of Dungannon, County Tyrone), and was based at Fairlawne in Kent. His line died out in 1789. The second son, Morgan, founded a cadet line who would resurface in the peerage after the senior line died out in the 1890s. The eldest, Gilbert, was 2nd Baron Barnard. His son Henry was a solidly reliable Whig politician, but never a leader. He was given the very lucrative post of Paymaster General of Ireland and sat on the Irish Privy Council, 1742-44, then became a Lord of the Treasury in 1749, as a client of his cousin the Duke of Newcastle (one of the Pelham brothers). He was also appointed to his great-great-grandfather’s post of Lord Lieutenant of Durham in 1753, starting the long family tradition as the ceremonial representative of the monarchy in the county. That year he succeeded his father as 3rd Baron Barnard, and the following year the King made his position as royal representative easier by raising him in rank, to Earl of Darlington (after the largest town in the southern part of the county). He died in 1758, a few years before his wife, Lady Grace FitzRoy, daughter of the 2nd Duke of Cleveland.

Lord Darlington’s sister, Hon. Anne Vane, also had an interesting, if brief, career at court, as ‘the Beautiful Vanella’ (as she was dubbed in the press), the mistress of Frederick, Prince of Wales. She was appointed as a maid of honour to Queen Caroline, Frederick’s mother, and by 1730 was linked to the Prince, by whom she had a son in 1732, the unrecognised child Cornwall FitzFrederick Vane, who died four years later, followed soon after by his mother, aged only 26.

The 2nd Earl of Darlington, as Viscount Barnard sat in Parliament as a Whig MP, and later held the mid-level posts of Governor of Carlisle, 1763, and Master of the Jewel Office, 1763 to 1782 (who oversaw the safety of the Crown Jewels). His chief interest was in modernising and improving Raby Castle, and carrying on his father’s role as Lord Lieutenant of Durham. He died in 1792 and was succeeded by William, 3rd Earl of Darlington.

Like his ancestors, William Vane sat in Parliament as a Whig, then took over as Lord Lieutenant of County Durham in 1792. He raised a regiment of cavalry to serve in the wars against France, but did little else to distinguish himself. He did, however, increase his family’s prestige as landowners, however, in positioning himself as heir to the name (if not the titles or lands) of his FitzRoy grandmother, but also as heir to the Pulteney Estate, as distant heir of his great-grandmother, Anne Pulteney, Duchess of Cleveland.

Anne’s nephew, William Pulteney was a significant politician (as Earl of Bath from 1742, and briefly Prime Minister for two days in February 1746), and a great acquirer of lands. In 1726 he purchased the Bathwick estate in Somerset, directly across the Avon from the City of Bath (connected today by the Pulteney Bridge). He also developed real estate in London (like Great Pulteney Street in Soho) and made himself guardian and then heir to the last member of the Newport family (earls of Bradbury) of Shropshire. He had aspirational family interests himself in that West Midlands county, by descent from the Corbets, important medieval marcher lords. In the early 1760s, the Earl of Bath had plans to transform the Newport family seat of Eyton, on the river Severn east of the town of Shrewsbury, but he died before anything could be completed. His heirs instead focused on Shrewsbury Castle, an ancient Norman fortress transformed into a residence in the sixteenth century, owned by the earls of Bradbury since 1666. It was further modernised by the Pulteney family in the 1780s, a notable early project for Thomas Telford. These Shropshire lands (which include the famous landmark, the Wrekin) did pass to the Vane family of Durham when the last Pulteney heiress (Laura, Countess of Bath) died in 1808; they maintained Shrewsbury Castle as a second seat until it was sold in 1924 to the local borough council.

By the start of the nineteenth century, William Vane, 3rd Earl of Darlington, began to quarter his family arms with the FitzRoy arms, added the Somerset and Shropshire estates of the Pulteneys, and pressed the inheritance claims of his wife, Lady Catherine Powlett, as daughter and co-heir of the last Duke of Bolton who died in 1794 (though most of the Powlett estates went to an illegitimate niece, and the Bolton baronial title passed to a cousin). In 1826, he ‘reminded’ high society of his connection to the last Duke of Cleveland by naming a new bridge over the Avon in Bath after him. So in 1827, King George IV recognised this kinship link by raising Darlington to the rank of Marquess of Cleveland, and then in 1833, Duke of Cleveland. The first Duke was made a Knight of the Order of the Garter in 1839 by Queen Victoria, then died in 1842.

It seemed the Vanes had finally reached the top of the aristocracy and Raby Castle was once again a princely seat in the North. But none of the 1st Duke’s three sons had male heirs and the dynasty’s senior line died out in 1891. Moreover, the family was outshone in political and social prestige by the junior line of the Marquess of Londonderry, first by Lord Castlereagh (later 2nd Marquess) one of the leading diplomats at the Congress of Vienna in 1814-15, then by the 3rd Marquess, a prominent soldier and diplomat, who took over as Lord Lieutenant of Durham when the 1st Duke of Cleveland died in 1842 (and the Londonderry branch would keep this office off and on until 1949).

Henry, 2nd Duke of Cleveland, was himself a soldier, attaining the rank of major-general in 1851 and retiring as a full general in 1863. He had a long career as a Whig MP in the House of Commons, from 1812 to 1842 when he moved into the House of Lords. He was mostly an absentee landlord in Bath, but focused on improvements to Raby Castle, where he built a neo-gothic entrance hall. He continued to gather the family’s great art collection here, refashioned one of its salons as a Jacobean gallery, and played host to visiting royalty (notably the Prince of Orange who became King William III of the Netherlands while at Raby in March 1849). He died in January 1864 and was succeeded by his brother William.

William, 3rd Duke of Cleveland, had also spent over forty years as an MP, using the name and arms of Powlett, setting himself up as heir of his mother. As heir, he lived at Harewood House (or Harewood Park), an eighteenth-century house on the edge of Windsor Great Park in Berkshire (still standing today, but privately owned). William Powlett (then briefly Vane again) reigned as duke for only eight months and died in September 1864.

His brother, Lord Harry Powlett (or Powlett-Vane), became the 4th Duke of Cleveland. He had been a diplomat in the 1830s, and in 1854 married Wilhelmina Stanhope, daughter of Earl Stanhope (Lady Dalmeny by her first marriage). Although they had no children, the Duke raised his step-son, Archibald Primrose, who later became famous as the Earl of Rosebery, Prime Minister in 1894-95. In London, the Duke and Duchess resided at Cleveland House on St James’s Square. In the countryside, the Duke owned over 100,000 acres: 55,000 in County Durham and 25,000 in Shropshire. Wilhelmina, Duchess of Cleveland, had been prominent at the early court of Queen Victoria, having served as a maid of honour at the coronation of 1838, then a bridesmaid in 1840. She later was a bit of a historian, delving into the history of her home at Battle Abbey near Hastings, writing a guidebook for visitors there, and an account of noble families whose ancestors were inscribed in the ‘Battle Abbey Roll’, a list of those who fought at Hastings in 1066.

Lord Harry and Lady Wilhelmina had acquired Battle Abbey in 1857 as a country seat, on the south coast in Sussex. This was the abbey commissioned by William the Conqueror to be built on the site of the Battle of Hastings to atone for all those killed that day. It was constructed in the 1070s and then dissolved as a monastery in 1538 on orders of Henry VIII who gave it to his faithful servant Sir Anthony Browne. Browne demolished most of the abbey and used its materials to reconstruct the abbot’s residence as a country house. In 1721, the Browne family sold the house now known as Battle Abbey to the Webster family, who held it for over a century, selling it to Lord Harry Vane. It became a favoured residence of the last Duke and Duchess of Cleveland, and the Duchess remained here as a widow until she died in 1901. It returned to ownership of the Websters, who converted it into a school in 1923. In 1976 it was finally sold to the state to be maintained by English Heritage, though the school still remains on the site.

When the 4th Duke of Cleveland died at Cleveland House in London in 1891, the Pulteney Estate in Somerset passed to a nephew, while the Vane estates in County Durham—Barnard Castle and Raby Castle—and in Shropshire passed to the next male heir, Henry Vane, who became 9th Baron Barnard. Interestingly, his eldest son Henry reunited the distant branches of the Vane/Fane family through his marriage in 1914 to Lady Enid Fane, daughter of the 13th Earl of Westmorland. Hon. Henry Vane also became Master of Foxhounds for one of the premier hunts in England, the Zetland, formerly known as the Raby, which covered huge amounts of County Durham and North Yorkshire. He died shortly before his father, meaning the barony, and the post of Master of Foxhounds, passed to his brother Christopher, who, as 10th Baron Barnard, picked up once more the old family post of Lord Lieutenant of County Durham in 1958. He died in 1964, and his son, John, the 11th Baron, was appointed to this post again in 1970 and held it until 1988. When he died in 2016, the Vane estates were valued at £94 million, currently managed by another Harry Vane, 12th Baron Barnard (b. 1959).

(images Wikimedia Commons)

I am grateful to the History of Parliament Trust, London, for allowing me to see the unpublished articles in draft on Charles and William FitzRoy, 2nd and 3rd dukes of Cleveland, for the 1660-1832 section, by Dr Robin Eagles.

Dear Dr Spangler,

Your fascinating piece on the Fitzroy dukes of Cleveland comments that ‘the second and third dukes, Charles and William FitzRoy, were very rich but unremarkable’. It was this strange discrepancy between their rank and wealth and their historical significance that piqued my interest a few years ago, when I came across the following passage from the diaries of the Earl of Egmont:

“Jan. 26, 1732

The marriage consummated Saturday last between William, Duke of Cleveland and Southampton, and Lady Harriet Finch, sister to the present Earl of Nottingham and Winchilsea, has been the talk of the town ever since. It has been concluding these three months between the two mothers, but kept so secret that even my Lord Nottingham knew nothing of it, for being a generous man they were sure he would not approve the sacrifice of his sister to such a kind of husband, who is said to be a greater fool than his father, and withal ill-natured, covetous, jealous, obstinate as a mule, and lascivious as a stone horse. He has not yet taken his seat in the House of Lords, nor will perhaps, his delight being altogether in low things and mean company, and his chief occupation to rub down his horses, for which his grooms give him a penny, which he counts all gain. Nothing, therefore, could colour the marrying such a brute (for just excuse there can be none) except the title of a Duchess and a vast jointure. Lady Harriet, an Earl’s daughter, having but five thousand pounds fortune, was not able on the interest of it to live according to her rank, and there was no prospect of her marrying elsewhere. But, unfortunately for her, the Duke, though he has a great estate, more than 100,000 l. a year, was able to make a settlement but of 1,200 l. a year, the estate being entailed, and passing to another family should he die without children. All my Lady, therefore, has for it, is to save what she can out of the annual rents, but whether this obstinate and covetous fool will suffer her is what time will show.

He knew nothing of the affair till the moment it was done: till two mothers concerted to meet at my Lady Nottingham’s in Bloomsbury Square, and bring their children with them by way of common visit, and then the Duchess of Cleveland, in an easy manner, asked her son if he cared to be married. The Duke answered ‘Yes’. ‘What do you say then’, said she, ‘to my Lady Harriet Finch? Will you marry her?’ ‘Yes’, replied he. ‘Why, then’, said she, ‘the sooner you do it the better; here she is, and my Lady Nottingham’s chaplain is at home. Let us send for him’. So, producing the writings she had prepared, the Duke took a pen which lay on the table, and signed them, and the minister, who waited in the next room, did his office.”

This passage amply bears out the suggestion that the 3rd Duke was not very bright. It is also evidently the source of the statement in his ODNB article that his estates were worth £100,000 p.a. But it seemed to me that that figure could not possibly be right: it would have made him more than twice as rich as the peers generally accounted the wealthiest at that time, such as the Dukes of Devonshire and Bedford. So I did a little research into the provision made by Charles II for his sons by Barabara Castlemaine, and the results are set out at the foot of this message. It seems clear that £10,000 a year is a fair estimate of the 3rd Duke of Cleveland’s income from sinecures, and that Egmont’s diary entry is either an error by him or a typo in the Historical MSS volume where it is to be found.

As you intend to write about the Dukes of Grafton, you may find helpful the following information about the remainder to the dukedom of Cleveland:

When Barbara Castlemaine was created duchess of Cleveland, countess of Southampton and Baroness Nonsuch, it was with remainders to her elder son Charles and her second son George, no mention being made of Henry (the future Duke of Grafton) who was not acknowledged until 1672, when he took the name Fitzroy and was made Earl of Euston. Thus the 3rd duke’s titles became extinct on his death without issue, as his cousin the duke of Grafton was not in remainder to them.

This may not have been widely known, however: the London Magazine had mentioned in 1735 the prospect of ‘the title of duke of Cleveland and Southampton falling to the duke of Grafton in default of issue’, and reporting the death of the 3rd duke in May 1774, added “The title, with 8oool. per annum, which is entailed on the title, comes to the Duke of Grafton, who now takes the title of Duke of Cleveland.”

Horace Walpole was under the same impression, writing in May 1774:

‘The Duke of Cleveland is dead: the greater part of his estate comes to the Duke of Grafton, and I believe either the title of Cleveland or Southampton. The rest of his fortune goes to his nephew, Lord Darlington.’

And Sir R M Keith wrote on 10 June 1774 (from ‘Memoirs and Correspondence (official and familiar) of Sir Robert Murray Keith, K.B.’):

‘I think the Duke of Cleveland [ie Grafton] knows what to do with his money, else I should be sorry for his new accumulation. I have seen few heads that could carry thirty thousand pounds a year, without ruling a little, and still fewer hearts that were the better for their possession: but I am sure black George bids as fair as any man of my acquaintance to be both happier and more beneficent, because he is rich. Pray, offer my respects to the Duke of Cleveland, and assure him I shall ever retain the warmest sense of the obligations I owe to the Duke of Grafton.’

In the event Grafton received the sinecures, bringing his total income to something approaching the £30,000 mentioned by Keith, but not the titles.

V best wishes,

Richard Chown

Charles II’s provision for his sons by the duchess of Cleveland

Charles duke of Southampton (later Cleveland), Henry duke of Grafton, and George duke of Northumberland [http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.asp?compid=22778]

Annuities charged on the Excise: in 1674 the king granted separate annuities of £3,000 to the three sons with remainders from one to the other. After George’s death in 1716 the dukes of Cleveland and Grafton received £4,500 each; and in 1774 the entire sum of £9,000 devolved on the 3rd duke of Grafton. The pension was redeemed in 1855-6 in return for a capital sum of £193,000.

Prisage and butlerage: In 1672 the king granted to George, with successive remainders in default of issue to his brothers, the duties known as prisage and butlerage on all wines imported into England, except through ports in the Duchy of Lancaster, the Duchy of Cornwall and the Principality of Wales. After George’s death in 1716 the income passed to Charles; and when the latter’s only surviving son William died without male issue in 1774, to the 3rd duke of Grafton. This income was exchanged in 1806 for an annuity of £6,870; the following year a third of the annuity was converted into funded stock to the value of £76,000. Finally in 1815 the remaining annuity of £4,580 was commuted and the capital fund increased to £229,000.

An annuity of £4,700 charged on the General Post Office was granted in 1669 to trustees for Barbara (then still countess of Castlemaine) for her life, with power to vary the uses of the trust; this she did in 1685, dividing the income after her death between Henry and George. When the latter died without issue in 1716 the entire sum passed to the 2nd duke of Grafton. The pension was redeemed in 1855-6 in return for a capital sum in stock of £91,000.

The ‘Honour of Grafton’: In 1673 the king granted the reversion of this Northants estate (after the death of the present possessor Queen Catherine of Braganza) to Henry earl of Arlington, with remainder to Henry Fitzroy and further remainders to Henry’s brothers. The income from the estate was reckoned at £6,000 in the 1750s and £8,000 by the late 1770s (when the duke received £5,000 p.a. net).

Sinecure offices: the office of Receiver-General of the Profits of the Seals in the King’s Bench and Common Pleas was granted either to Charles or to Henry (it is unclear which) but in any event it passed to the 3rd duke of Grafton in 1774. It was redeemed by the then duke in 1825 for an annuity of £843, which was commuted in 1883 for £22,714, 12s. 8d.; the office itself was abolished in 1845. The dukes of Cleveland were granted the office of Comptroller of the Seal and Green Wax [or Hanaper] Office. The profits are not known, but fell short of the 3rd duke’s expectations in the late 1740s when he petitioned (successfully!) for an annual supplementary grant.

This gives incomes as follows, excluding the above sinecures: until 1716, Northumberland received £5,350 plus prisage; Grafton, £5,350 plus the Northants income; and Cleveland, £3,000 pension plus £4,000 jure uxoris. From 1716 Cleveland’s income rose to £10,500 and Grafton’s to £15,200. After 1774 the duke of Grafton received the income from all these sources, amounting by 1800 to well over £25,000. Some £20,500 of this derived from pensions and offices which were eventually redeemed for a total of £536,000.

LikeLike

Thank you so much, Richard, for this treasure of information! I agree with you that £10,000 is a more likely figure. But what a windfall for Grafton by the end of the century! It would be such a great project for someone to pull together all this type of financial and political information for *all* of Charles II’s sons (and throw in the dukes of Berwick and Albemarle too for completeness), to create a thorough comparative study.

LikeLike