The court of Kaiser Wilhelm II is remembered for its excessive militarism—the Prussian sabre rattling that encouraged the Austrian emperor to send such a strong ultimatum to the Serbs in July 1914 that made World War I inevitable—an excess that ultimately brought about the demise of both monarchies and the dukes and princes that supported them. What is less well known is that the court in Berlin in the first years of the twentieth century was also a hotbed of intrigue headed by a group of nobles close to the Kaiser whose attachments to the extremes of nationalism, even occultism, led to much of this militarism. Two members of this coterie were created princes: Philipp zu Eulenburg and Bernhard von Bülow. Both were members of ancient Junker families, but they only reached the very top of the aristocratic hierarchy at the very end of the period of aristocratic hegemony in Germany. This post will look at these two families in comparison to see how they scaled this ladder. Besides the two most prominent members, there were many others who achieved prominence as ministers or generals, and in the case of the Bülows, as musicians too. The first Prince zu Eulenburg scandalised society when whispers about his homosexuality were dragged in front of the courts and the world’s newspapers in 1906-08. The first (and only) Prince von Bülow was also accused of ‘deviancy’, but it didn’t stick—nevertheless he too was brought down, a year later following another scandal in the press, a scandal that nearly lead to war with France five years before anyone had even heard of the Archduke Franz Ferdinand. The ‘Eulenburg Affair’ and the ‘Daily Telegraph Affair’ were instrumental in the melt-down of the Kaiser’s regime, long before the First World War had begun.

But the more compelling story, from the perspective of this blog, is the continuity and sheer volume of the history of service to monarchy in both Eulenburg and Bülow families, both tracing their roots back to the earliest days of the Holy Roman Empire. And it is interesting that both made contributions to the history of classical music, in the context of the nationalist music movement of Franz Liszt and Richard Wagener.

The Eulenburg family was originally from Saxony, in a region in what was originally ruled by the margraves of Meissen and later became the Electorate of Saxony. The earliest ancestors, from the 1180s, were ministeriales (the administrative class at the bottom of the nobility) in service of the margraves. In fact, the first Meissen margraves of the previous century came from Eulenburg itself—known in the Middle Ages variably as Ileburg, Ilburg, or Yleborch, and today Eilenburg. The ancient fortified hilltop here (the ‘Burgberg’), overlooking the river Mulde, was given to this vassal family, and they took their name from it, expanded its buildings, then sold it back to the margraves by the end of the fourteenth century (and it remained a Wettin seat for centuries).

By this point the family had moved on, first to Lusatia, where Botho von Ileburg was governor in 1450, and then to the far northern reaches of the expanding German lands, territory conquered by the Teutonic Knights in the Baltic, soon known as the Duchy of Prussia (and later as ‘East Prussia’). Botho’s son Wend fought for the Teutonic Knights and was rewarded with an estate in 1468 at Gallingen, fairly close to one of the Order’s great fortresses, Bartenstein (today’s Bartoszyce, in Poland). The Eylenburgs or Eulenburgs turned the manor house here into a castle in 1589, expanded into a three-wing palace in 1745, and renovated again in the 1830s in a neo-gothic style. The estate at Gallingen in the nineteenth century covered a whopping 15,000 acres. In 1945, its owner, another Botho, was carried off by the Red Army, and in the settlement that drew up the new borders dividing East Prussia, it became part of Poland—its population was expelled and it was renamed Galiny. The castle has been recently restored and opened as a hotel.

A short distance to the northeast, two estates, Prassen and Leunenburg, were acquired by marriage in 1490. Prassen became the family’s chief seat from about 1610, where they built a new manor house (while the older castle at Leunenburg was destroyed in war with the Swedes and never restored). A curious legend is attached to Prassen Castle in the eighteenth century: a wedding was hosted here by a family of ‘Bartukken’ (the local version of gnomes); in one version, the wedding was interrupted by an Eulenburg family member and they were cursed to only ever have thirteen members alive at one time; in another, the king of the Bartukken wed an Eulenburg daughter—she vanished into thin air, but the family was promised good fortune, and soon after (1786) they were raised in rank from barons to counts. Like Gallingen, Schloss Prassen was also rebuilt in the early nineteenth century as a neogothic castle. It was also confiscated in 1945 and has fallen into ruin. Today this estate is known as Prosna in Polish.

Just across the border, in the Russian exclave of Kaliningrad, is the village of Klimkova, which for most of its history was the estate and castle of Wicken. It was acquired by the Eulenbergs by marriage in 1766. Completely destroyed in 1945, the only reminder of the family’s existence here is the still fairly large number of Protestants in an otherwise very Orthodox or Catholic land.

By the seventeenth century, there were various branches of the Eulenburg family, and they served the margraves of Brandenburg (who were also dukes of Prussia) as chamberlains, diplomats and generals. The family began its rise in the first years of the eighteenth century when Gottfried of the Plassen line was named ‘Freiherr’ (baron) in 1709, and from 1726 served as Lord Marshal of the Court of the newly constituted Kingdom of Prussia, and from 1728, as Minister of War and member of the King’s Privy Council. He inherited the lands of the senior branch of the family, at Gallingen, while his son married the heiress to the neighbouring estate of Wicken, so by the time his grandson, Ernst Christoph, came of age, he had amassed a sizeable estate in East Prussia, enough for the King to elevate the family to the rank of Count (1786). So, not really the work of gnomes.

The Eulenburgs by tradition used ‘zu’ rather than ‘von’ in the title, which usually (but rather vaguely) implies sovereignty over a territory, not just being ‘from’ there (see notably the princes ‘von und zu’ Liechtenstein); in this case they did not even own the original castle back in Saxony from which they took their name, so I am not certain why they used ‘zu’—but they did. The first Count zu Eulenburg had six sons, and divided the patrimony into three entailed estates: Prassen, Wicken and Gallingen (the other three sons had to fend for themselves). The family maintained a base in the capital of royal Prussia, Königsberg (today’s Kaliningrad). ‘Eulenburg House’ was one of the many grand aristocratic palaces on a main street of the city, Königstraße (today known as Frunze street), and is remarkably one of the few to have survived the near complete levelling of the city in World War II. The family also maintained a country estate, Perkuiken, northeast of the city.

The three senior lines survive today, but it was the descendants of the sixth son, Friedrich Leopold, who rose to the highest rank. His elder son, Count Friedrich Albrecht was a very gifted scholar; he studied law then rose through the ranks of the Prussian Ministry of the Interior in the 1840s-50s. He then shifted to external affairs, and led a successful diplomatic and trade expedition to Japan and China, 1859—Prussia’s first foray into East Asia. He was recalled to Prussia in 1862 and once more to domestic affairs, now as Minister of the Interior. Over fifteen years he modernised the administrative structures of the Kingdom of Prussia and extended ‘Prussianism’ into newly acquired territories, notably the former kingdom of Hanover and the duchies of Schleswig and Holstein, annexed in 1866.

Count Friedrich Albrecht was succeeded as Prussian Minister of the Interior in 1878 by his second cousin, Count Botho Wendt zu Eulenburg. He tried to carry out his cousin’s planned reforms, but clashed with the more conservative Chancellor Bismarck, so resigned in 1881. A decade later, after Bismarck’s retirement, he was once again Minister of the Interior, but also Minister-President of Prussia (aka, Prime Minister) from 1892 to 1894.

Meanwhile, Count Botho’s brother August played his part in maintaining the family’s prominence at court: as a young man he became close to Crown Prince Frederick—with the expectation that he and his brother (and his cousin, below) would play prominent roles in the more liberal regime that seemed imminent once the Crown Prince succeeded as king of Prussia and emperor of Germany. In 1883, Count August was promoted within the household to the post of Grand Master of Ceremonies, a position he would retain until 1914, with the addition of the even higher office of Grand Marshal of the Court and Household from 1890. Crown Prince Frederick did succeed to the throne, as Emperor Frederick III, but died after only three months in 1888. Eulenburg retained his position at the head of the Imperial household under Frederick’s son, William II, and was promoted again in 1907 to Minister of the Royal Household. Even after the fall of the monarchy in 1918, Count August continued to act as a formal representative of the royal family until his death in 1921.

The Eulenburg who helped ensure his cousins Botho and August rose to such high ranks within the imperial government and household was Philipp zu Eulenburg, whose close relationship to Kaiser Wilhelm II brought the family to the pinnacle of its power, but also nearly to its ruin.

Count Philipp’s father, Philipp Konrad, had a fairly middling career, a lieutenant-colonel in the army and a chamberlain at court. It was his marriage in 1846, however, that propelled his branch of the family from moderate landowners to one of the richest in Prussia. His wife, Alexandrine, Baroness von Rothkirch and Panthen, was grandniece of Karl, Baron von Hertefeld, Lord of Liebenberg. These estates spread Eulenburg interests to the far west in Cleves and to the north of Brandenburg. The Eulenburg arms was now quartered with a red hart for Hartefeld.

The Hertefeld family were knights in the Rhineland dating back to the fourteenth century, based at Haus Hertefeld in Weeze, near the modern Dutch border. Originally Hertefeld was an independent imperial fief but from 1358 it was subject to the dukes of Cleves. The house was rebuilt as a baroque palace in 1700, and though it mostly burned down in February 1945, was partly rebuilt and became the Eulenburg family seat as they had lost their properties in the east. It was further restored between 1998 and 2006, rebuilding the main tower and the baroque dome—it remains the private residence of the family.

The family also acquired Kolk House by marriage in the early sixteenth century. This was a moated castle in the village of Uedem, near Xanten, also in the Duchy of Cleves. The original fourteenth-century manor house was rebuilt in the seventeenth century in Dutch baroque style—at first in 1632, then again in 1648 after its destruction in the Thirty Years War. It was remarkably undamaged in the Second World War, and today is the seat of the younger son of the family.

In 1614, after the extinction of its ducal family, the Duchy of Cleves was awarded to the electors of Brandenburg, and the Hertefeld family began to focus their attentions on the rising power of the court in Berlin. Samuel von und zu Hertefeld entered the service of Electoral Prince Friedrich (son of the Elector), and after this prince became Elector himself, was appointed to positions of authority, first as Master of the Hunt in Cleves, 1697, then Grand Master of the Hunt of Brandenburg in 1704. By this point, the Elector had become King Frederick I of Prussia, and he elevated Hertefeld’s title as well, to baron. The new Baron von Hertefeld masterminded land reclamation projects in central Brandenburg (the Havelland) and in East Prussia, amassed a huge personal fortune, and was named Secretary of State for the Interior in 1727. He died in 1730 at Liebenberg.

The manor of Lienbenberg in northern Brandenburg (about 50 km north of Berlin), had been acquired by the Hertefeld family in 1652. The former knight’s manor house here would be rebuilt by the Samuel’s heirs in 1743, then expanded and redesigned in Historicist style by the Eulenburgs in 1875. Its chief attraction was its extensive forests with abundant game with which Philipp zu Eulenburg could entice the Kaiser to visit and thus gain his favour. It was thus an incredible windfall for the family. Confiscated by the East German government after 1945, Liebenberg was run for years as a supply centre for the Socialist Party who also used it as an educational facility and a space for social events and a guesthouse for prominent party members. In 1991 it was privatised and sold; about 2000 it was acquired by Deutsche Kreditbank and converted into a hotel and conference centre, with other buildings being used for an organic farm.

Count Philipp gained another asset from his mother Alexandrine. She was musical and had established a friendship with Cosima von Bülow, daughter of the composer Franz Liszt, and later wife of Richard Wagner (see below), who encouraged her son’s musical and philosophical education. His place in the circle of the growing cult of Richard Wagner—using high art to advance the cause of nationalism—led him also to espouse the racist ‘Aryanist’ ideologies of the French aristocrat Gobineau, and he may even have had a sexual relationship with him. Young Philipp became a vocal nationalist and anti-semite. He feared instability in Germany’s new empire after 1870, so grew to oppose the spread of democracy but also the power of the Catholic Church, since it divided the loyalties of its adherents between Berlin and Rome.

Like many members of his family, Count Philipp became a diplomat, and worked in Paris and Munich for much of the 1880s. He became increasingly drawn to the life of an artist, penning some plays, short stories and musical compositions: the collection ‘Old Norse Songs’ was published in 1892, as were the ‘Rose Songs’ (Rosenlieder) which were quite popular during his lifetime. He also added to his branch of the family’s fortune and influence through a marriage in 1875 to Augusta Sandels, grand-daughter and heiress of Johan August Sandels, Governor-General of Norway, 1818, and Swedish Field Marshal—he had gained fame as a general who defeated the Russians in 1808, then Napoleon in 1813-14, and was rewarded with lands in Swedish Pomerania. In 1815, Pomerania was granted to Prussia and the general was created Count Sandels, a title which later passed to his grand-daughter and her husband.

Crucially, from about 1886, Count Philipp became very close to Prince Wilhelm of Prussia (12 years younger)—almost too close, which made Chancellor Bismarck uncomfortable. In particular, Eulenburg introduced the young Wilhelm to the occult, consulted clairvoyants, led séances. Perhaps to remove him from the scene, Bismarck sent Eulenburg to Oldenburg as ambassador from Prussia in 1888. By the end of that year, however, Wilhelm had succeeded his father as Kaiser, and Eulenburg was back at court. He was courted by those aspiring for power as the closest friend of the new Kaiser—and was a central player in Bismarck’s overthrow in March 1890.

By 1894, Eulenburg, though holding no official post except ambassador (to Munich, 1891-93; to Vienna, 1893-1902), was almost as powerful as the Chancellor, using his personal influence with the Kaiser to change policy, appointing his cousins to eminent posts in government and the household (Botho and August, as above), and forging an alliance with Bernhard von Bülow—pushing him to the top spot as Chancellor in 1900 (see below). From his post in Vienna, he continued to support Wagnerism and antisemitism, yet he maintained a close relationship with Jewish banker Nathaniel Meyer, Baron von Rothschild, who left him 1 million krones. The late 1890s was a time of increasing suspicion of sexual deviancy at the court of Berlin, with the Kaiser depicted mostly as a hapless victim if not an active participant (which is unlikely). Indeed, in 1897, Count Philipp’s younger brother Friedrich was charged by the Army of being a homosexual; and in 1898, one of Eulenburg’s closest friends, General Kuno von Moltke, was accused by his wife of preferring sex with Eulenburg. Even the Kaiser’s wife, Empress Auguste, accused her husband of spending more time with Eulenburg than with her or their children, suggesting that they were themselves having an affair.

A homosexual affair between Eulenburg and the Kaiser seems unlikely, but Wilhelm did reward his friend’s loyalty with the greatest prize, elevating him to the rank of Prince zu Eulenburg und Hertefeld, with the style of ‘serene highness’ in 1900. Yet already the new prince expressed fear in personal letters of the now near constant stormy and explosive rages of the Kaiser. They began to disagree over military strategy, as Philipp was pro-war but against the expansion of naval power, a project close to Wilhelm’s heart as the best way to show up his British relatives.

In 1906-07, Prince Eulenburg’s position at the centre of the Kaiser’s court began to crumble following a series of scandals known as the Harden-Eulenburg Affair. At the heart of the affair was factional politics: Eulenburg and Bülow versus Friedrich von Holstein, the Kaiser’s leading advisor on foreign affairs. Holstein had been angered by the failure of the Algeciras Conference (over the colonial partition of Morocco) in April 1906, and made a show of resigning—then was surprised when the Kaiser accepted his resignation on the prompting of Eulenberg. So Holstein sought revenge. He challenged Eulenberg to a duel, which the latter declined, so Holstein turned instead to social discrediting by means of the sensationalist media always eager for a juicy story. Though it has never been proven, it is thought he encouraged the journalist Maximilian Harden to publish articles in Die Zukunft abut the so-called ‘Liebenberg Round Table’, a cult of homosexuals who dominated the Kaiser and his court. The articles accused Eulenburg and his friends of being ‘too soft’ to go to war with France over Morocco and suggested that he was in fact being blackmailed by a French diplomat in Berlin, Raymond Lecomte, with whom he was having an affair. Eulenburg and Lecomte were in fact hunting buddies, spending time in the forests of Liebenberg, and Lecomte did suspiciously burn his papers after the article’s publication. Harden decried Eulenburg’s love of singing, and called for ‘real men’ like Bismarck to return to the helm of the Imperial government.

The affair spread in 1907 when Kuno von Moltke sued Harden for libel, and lost. An early champion of gay rights, Magnus Hirschfeld, testified that Moltke was indeed a homosexual, but argued that there was nothing wrong with that. The judge overturned the jury’s decision, so Harden settled out of court. Another campaigner for gay rights, Adolf Brand, published a pamphlet saying that Chancellor von Bülow was a homosexual, so a new case was started, Bülow vs Brand, which involved Eulenburg who testified that he had never committed ‘depravities’ with Bülow or any other men. Eulenburg then accused Harden of being a ‘rascally Jew’. Harden next set himself up in April 1908 in a fake trial with a fellow journalist in Munich, in which two Bavarian fishermen testified to having been sodomised by Eulenburg back in the 1880s when he was on holiday there—thus also accusing Eulenburg of perjury due to his testimony in the other trial. This led to the Prince’s arrest in May and the police conveniently seized and burned his papers; later discoveries revealed that Eulenburg did have a close relationship with one of the fishermen (Jakob Ernst), as did the then Prince Wilhelm. The Kaiser now wrote to Eulenburg saying he wanted no homosexuals at his court and never wanted to see his former friend again. Other friends wrote to him in prison that he should save the Kaiser’s honour and his family’s reputation by committing suicide. All of his friends (including Moltke) turned against him.

Eulenburg struck back by accusing Jakob Ernst of being a drunk (even by Bavarian standards), and that the entire affair was a Catholic plot (Jesuits, Bavarian separatists) to destroy him, a champion of Protestant Prussian values. Several working-class men testified against him. In mid-July 1908, the Prince collapsed in court and the judge ruled him unfit for trial. He was declared unfit twice a year from then on until his death in 1924. By late 1908, Maximilian Harden turned his attention to the Kaiser himself, since he thought he had been in the thrall of this den of homosexual vipers (today we might call them ‘catty queens’ sitting at the back of a darkened disco) due to something they had on him. He called for Holstein to take the lead in government and lead Germany to war as a means of purifying the nation.

Germany did go to war in 1914, though without Prince Philipp zu Eulenburg anywhere near the levers of government, and caused the death of the Prince’s beloved second son. Count Botho, who went by second name Sigwart, shared many of his father’s artistic traits: drawn to music, he was invited as a young man by Cosima Wagner to Bayreuth to learn the trade, then studied with Max Reger at the Conservatory in Leipzig, completing a doctorate on a sixteenth-century German composer in 1907. He married the singer Helene Staegemann and composed songs for soprano, as well as an organ concerto, a melodrama for orchestra (‘Hector’) and an opera, the ‘Song of Euripides’ (1915). That same year he joined the army and was killed in Galicia.

Sigwart’s death devastated the Prince, who spent the rest of his life trying to contact him in séances. By December 1917, Eulenburg was in despair and wrote to friends that Germany was losing the war because of the Kaiser and the Jews. In later years he claimed he would have stopped the war from happening at all if he had still been ambassador to Austria-Hungary in 1914.

Prince Philipp’s eldest son, Friedrich Wend, had an interesting career himself as 2nd Prince zu Eulenburg und Hartefeld and Count von Sandels. As a young man he befriended Rudolf Steiner, an Austrian occultist and founder of ‘Anthrosophy’ the study of accessing the spiritual world. Steiner had been a friend of Count Sigwart and tried to communicate with him after his death in 1915. Once he succeeded his father as head of the family, Friedrich Wend became a leading member of the conservative landowners party in Prussia, and was instrumental in convincing them to combat Bolshevism and gain the support of the masses by joining with the Nazi Party in its surge to power in Germany. Indeed, Hermann Göring lived at the estate that neighboured Leiebenberg, so social connections were forged. The Prince fell from favour however due to his niece’s activities as part of the anti-Nazi resistance, and his own efforts to petition the government to release some religious prisoners in 1941—seemingly as a result, his son Wend was posted to the Eastern Front, then to Italy, in both cases the most dangerous places in the war, and he was captured in April 1945 by American troops (probably saving his life). He fled with his wife to their properties in West Germany, and, soon joined by their son, rebuilt the property of Hartefeld.

The 2nd Prince died in 1963, followed by Wend, the 3rd Prince, in 1986. The current prince is Philipp (b. 1938), who presides over his two sons who manage the two remaining family properties with their families: Friedrich (b. 1966) in Hartefeld and Siegwart (b. 1969) at Kolk.

Another family that rose slowly to the top of the Prussian aristocratic hierarchy through centuries of service were the von Bülows. Only one of them was named a prince, which earns this family a place among the dukes and princes, but like the Eulenburgs—in fact even more so—their dynastic history includes some very colourful stories.

In the early thirteenth century, a knight named Gottfried took the name of a small village in Mecklenburg, Bulowe, which in turn took its name from the local Wendish word for oriole, bülow, which from then on appeared as an element of the family coat of arms. The Wends were a Slavic people, gradually being pushed out of their Baltic principalities by ever increasing Germanic populations, and the dukes of Mecklenburg themselves—as seen in an earlier post on this site—retained a certain Slavicness in their bloodline, all the way to the twentieth century. Their German vassals, being so close to the Baltic and the Scandinavian realms spread northward, so there were branches of the von Bülow family who earned a place within the Danish and Swedish nobilities as well (the Swedish branch known as the Bylow). The family landholdings straddled the frontier between Mecklenburg and Holstein to the west, and in 1470 they added the significant estate of Gudow in the neighbouring duchy of Saxony-Lauenburg. The lord of Gudow was one of the political leaders of this duchy as hereditary land marshal (until 1882); their castle housed the ducal archives. A new castle was built here in the early sixteenth century, then remodelled along neoclassical lines in the 1820s; it remains one of the primary properties of the Bülow family to the present day.

As with many noble families of the Holy Roman Empire, their status was raised through the church, and in this case the Bülow family had four bishops of nearby Schwerin in the fourteenth century. About this time, a family shrine was established at Doberan Minster near the Baltic coast. This monastery was founded by the local dukes in the 1170s, the first in Mecklenburg. In the sixteenth century, it was converted into a Lutheran church. The Bülows restored it in 1874, and its ceiling proudly sports the Bülow arms.

Over the centuries, the Bülow family became one of the largest landowners in Mecklenburg, and provided the dukes of Mecklenburg and the neighbouring margraves of Brandenburg with generals, courtiers and statesmen, and split into many, many sub-branches. One of these was based at Dennewitz, southwest of Berlin near the frontier with Saxony, and contributed two generals to the army of Frederick the Great, then one of the leading commanders of the next generation in the fight against Napoleon, Friedrich Wilhelm von Bülow. He was a member of the inner circle of King Frederick William II, and in the 1790s was assigned to be military instructor to the King’s nephew, Prince Louis Ferdinand of Prussia. By 1813 he was a lieutenant-general and helped defeat a French army—at Dennewitz in fact—in September of that year, preventing an attempted occupation of Berlin and turning the tide of the war. He was rewarded with the title of count (Bülow-Dennewitz) and the next year was promoted to full general and given the task of driving the French out of the Low Countries and joining his armies to those of General Blücher for the invasion of France itself. In the months that followed Count von Bülow was named Commander-in-Chief of East Prussia, with his base in Königsberg, but was soon recalled to fight with Blücher again on the plains of Waterloo for Napoleon’s final defeat. He died a year later.

The famous General von Bülow’s country seat was at Schloß Grünhoff, in East Prussia on the Baltic coast—a district called Samland, west of the city of Königsberg. The castle, originally built by the Elector of Brandenburg and Duke of Prussia in 1697 as a hunting lodge, was rebuilt by his son in the 1850s. It had also been the site for many years of one of the largest stud farms in the region, dating back all the way to the era of the Teutonic Order (fourteenth/fifteenth centuries). It survived World War II and today, as Roschino, in the Russian district of Kaliningrad, is being renovated.

Another line of the family was based at Essenrode, near Helmstedt across the border in Hanover. In the eighteenth century they served the electors of Hanover (also kings of Great Britain) in various administrative roles. Another Friedrich Wilhelm von Bülow was a prominent judicial official in Hanover then aided Prussia in its takeover of that kingdom after 1806. His first cousin, Count von Hardenberg, had recently become Chancellor of Prussia, and promoted his career. Having been successful in Hanover, Friedrich Wilhelm was given the task of also incorporating occupied Polish and Lithuanian territories into the Kingdom of Prussia, then those of occupied Saxony, and after the war was Oberpräsident (civic governor) of the new Prussian province of Saxony. Like his cousin from the Dennewitz branch, he too was raised in rank to count, 1816. His brother Hans was also a successful politician: named Minister of Finance of the new Kingdom of Westphalia in 1808, then transferred to the same post in Prussia from 1813-17. He was then Minister of Commerce, 1817-25. His lasting achievement as a financial policy maker for Prussia was to create a system of customs barriers that made Prussia wealthy and made other German states want to join Prussia in a customs union—the first steps towards German unification later in the century.

Essenrode Manor had been built in 1738 by an earlier Bülow (the estate itself had been acquired in the 1620s, with an old moated manor house from the fourteenth century). In 1837 it was sold to the von Lüneburg family, an illegitimate branch of the House of Brunswick, who still own it today.

The branch that gave us our single Bülow prince moved from Mecklenburg into Danish service in the eighteenth century. Baron Heinrich von Bülow was a diplomat who married the daughter of a prominent diplomat Wilhelm von Humboldt—better known as a political philosopher and educational reformer—and rose to become Prussian Foreign Minister, 1842-45. His nephew Bernhard Ernst worked for the King of Denmark and represented his interests as Duke of Schleswig and Holstein in the German Diet in the 1850s. Here he got to know Otto von Bismarck, forging a bond between their families that would persist for the next generations. In 1862 he became Chief Minister of the Grand Duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, then ten years later was appointed by Bismarck, now Chancellor of the new German Empire, to be Secretary for Foreign Affairs, and he remained Bismarck’s right-hand man in diplomatic policy until his death in 1879. It was Bernhard Ernst’s son Bernhard Heinrich who rose even further to become prince and Chancellor of the Empire.

Bernhard Heinrich von Bülow was raised near Hamburg at a villa owned by his mother’s family, the Rückers of Hamburg (today known as the Voss’sche Villa), in Klein Flottbek, on the north bank of the Elbe west of the city. He entered German foreign service in the 1870s, and became particularly useful to Chancellor Bismarck as a diplomat in Russia in the 1880s, helping to forge better ties with Germany’s most powerful neighbour to the east. In 1888 he was named Ambassador to Romania, then to Italy, 1893.

In 1897 he was appointed Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, and in fact was the premier minister for the Kaiser since the Chancellor, Prince Hohenlohe, was very old. As director of Imperial policy, Bülow stressed colonial expansion, which annoyed France and the Netherlands, and an aggressive expansion of the Imperial Navy, which alienated Britain and Russia. He was elevated within the Prussian nobility to the rank of count in 1899. When Hohenlohe retired in October 1900, Bülow moved into his place as Chancellor of the German Empire and Prime Minister of Prussia. His government’s successful defiance towards France in a colonial clash over Morocco led the Kaiser to promote him to the rank of prince, which coincided with celebrations for the wedding of the Crown Prince, in June 1905. A prince needed a large fortune to sustain this dignity, and in 1904, he inherited five million marks from a cousin, Wilhelm von Godeffroy, a Berlin banker.

Things began to unravel for Prince von Bülow during the Eulenburg Scandal of 1907, as detailed above—he too was accused of being part of the homosexual circle of ‘court deviants’, but successfully sued his accusers for libel. But early in 1908, Wilhelm II made offensive and embarrassing anti-English comments to a journalist from The Daily Telegraph, and the Chancellor failed to stop its publication; his relationship with both the Kaiser and the Reichstag broke down and he resigned in June 1909. The official reason given was over his failure to pass a bill on inheritance tax. But his career was not over: in 1914 he was appointed Ambassador to Italy to try to convince King Victor Emmanuel to enter the war on the side of Germany and Austria-Hungary. The Prince tried to broker a deal between Italy and Austria-Hungary (over possession of South Tirol, Trieste and other territories), but in May 1915, Italy declared war on Austria-Hungary, and Ambassador von Bülow left Rome. He lived out of the spotlight for the next decade and died in 1929.

Bernhard von Bülow was aided in his Italian diplomacy by his marriage back in the 1880s to Maria Anna Beccadelli, Princess of Camporeale, intimately connected to high-ranking Italian politicians as the step-daughter of a former Italian prime minister, Marco Minghetti. The Bülows purchased a villa in Rome, the Villa Malta and lived there much of the time after 1909. Built on the Pincian Hill, near the Villa Medici, the villa had been an old country estate of the princely Orsini family since the sixteenth century, then passed through several interesting owners, including the Order of Malta in the seventeenth century (hence the name), the Bavarian royal family between 1827 and 1878, then by a Count Bobrinski (a descendant of Catherine the Great and Gregory Orlov) who rebuilt it in a more Romantic style. Since World War II it has been owned by the Jesuits.

Prince von Bülow had no sons, and his brothers pre-deceased him, so there were no other princes von Bülow. His wife Maria Anna, besides providing useful links to Roman political culture, also provides and interesting link to the second most well-known member of this family. As a young woman, she had been a pupil of the Hungarian composer Franz Liszt, and thus would have known Liszt’s daughter, Cosima (about ten years older), and her first husband, Hans von Bülow. These relationships also bring us back into the orbit of the composer Richard Wagner, whom we encountered above in the context of Philipp zu Eulenburg. Cosima scandalised Europe in 1870 when she divorced Hans and married Wagner.

Hans, Freiherr von Bülow, was a very distant cousin to Bernhard von Bülow. He was born in Saxony where his branch had entered service of the electors and later kings of Saxony. His father, Karl Eduard, was a novelist and an early proponent of ‘German studies’ as a new branch of literary scholarship. From a young age Hans became a student of music, and was apprenticed to the great piano virtuoso and composer, Franz Liszt—in 1857 he married his daughter Cosima. Hans von Bülow swiftly became known as a conductor and pianist himself, and was appointed Hofkapellmeister to the court of the King of Bavaria in Munich in 1864, and director of the Royal School of Music in 1867. A devoted Wagnerite, he conducted the premiers of the operas Tristan and Isolde (1865) and Die Meistersinger (1868). His daughters were even named for Wagnerian heroines: aside from Isolde, there was Senta (from Flying Dutchman), Elisabeth (from Tannhäuser) and Eva (from Meistersinger).

But Von Bülow’s conducting and performing schedule kept him away from his wife. Cosima was also drawn to the great master, and, after having several children with Wagner, demanded a divorce and was finally granted it in 1870. Hans broke permanently with Wagner, but his career continued to flourish. He composed and made transcriptions of larger works for piano, and premiered new compositions such as Tchaikovsky’s first piano concerto in Boston in 1875. In 1880 was appointed Hofkapellmeister in the court of the Grand Duke of Saxe-Meiningen, where he developed its orchestra into one of Europe’s leading ensembles (and hired a young Richard Strauss as his conducting assistant!). From 1887 to 1892 he served as principal conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic—the crowning position to his career as one of the most famous musicians in the world—and died two years later

Neither the Prince-Chancellor nor the Baron-Conductor left male descendants, but there were plenty of other family members to carry on the name in the twentieth century. In the military, there was Field Marshal Karl von Bülow, commander of the German Second Army in 1914-15, who defeated the French at Charleroi in the first month of the war; and Walter von Bülow-Bothkamp, an ace fighter pilot killed in action in 1918.

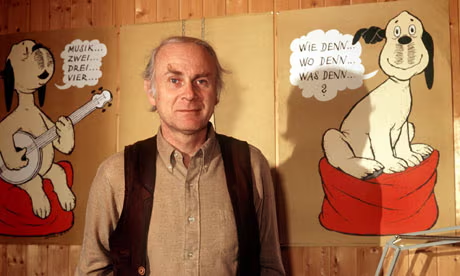

In the world of the arts, there was Vicco von Bülow, known as ‘Loriot’—a name taken from the family’s oriole namesake, a well-known comedian and cartoonist in the 1950s, who voiced his own cartoon dog Wum on German television in the 1970s. Later in life he too was an important figure in the world of classical music, as a director of operas in the 1980s-90s, notably a narrated version of Wagner’s Ring.

Finally, back in the world of politics, there was Frits Toxwerdt von Bülow, a Danish lawyer who became Justice Minster in Denmark in 1910, and later Speaker of the Landsting, the upper house of the Danish parliament, in 1920. His grandson Claus once again ties this blog to world of aristocratic scandal. Although he used the surname ‘von Bülow’, this was in fact his mother’s name; his father was Danish playwright Svend Borberg. Claus von Bülow moved to Britain and established himself as a lawyer and socialite in the 1950s. In 1966, he married Martha Crawford, better known as ‘Sunny’, the daughter and heiress of an American utilities magnate and the former wife of the Prince of Auersperg. In 1982, Claus was accused of attempting to murder Sunny by means of an insulin overdose, but was declared innocent after appealing an initial conviction—the central story of the book and later film Reversal of Fortune (1990), starring Jeremy Irons and Meryl Streep. Sunny lived on in a vegetative state for twenty-eight years until 2008, and Claus died in 2019. They had a daughter who, probably not coincidentally, they named Cosima von Bülow.

As an interesting, but actually unrelated, coda: we see a family called Eulenburg in nineteenth century who in a sense tie together the themes of sexuality and music in this blog. The Jewish Eulenburg family of Leipzig converted to Protestantism in the 1840s, and started a music publishing house in 1874. The founder’s brother, Albrecht Eulenburg, was a prominent sexologist. The family were expelled from Germany in 1939 and moved most of their operation to London. In the 1950s they were incorporated into the Schott publishing house, though the Eulenburg scores are still published and very recognisable on the shelves in their canary yellow.

Some interesting further reading:

- John Röhl, The Kaiser and His Court (Cambridge University Press, 1994)

- Norman Domeier, The Eulenburg Affair: A Cultural History of Politics in the German Empire (Boydell & Brewer, 2015)

- Alan Walker, Hans von Bülow (Oxford University Press, 2009)

- Katherine Anne Lerman, Chancellor as Courtier. Bernhard von Bulow & the Governance of Germany, 1900–1909 (Cambridge University Press, 1990)

(images Wikimedia Commons)

One thought on “Eulenburg and Bülow princes: two scandals that shook the Prussian court”