The woman at the centre of the historical drama The Mirror and the Light—though she doesn’t say very much—is Jane Seymour, third wife of Henry VIII of England and mother of the future king, Edward VI. Hilary Mantel’s trilogy focuses on the rise and fall of Thomas Cromwell, from a tradesman’s son to chief minister of the King and Earl of Essex, but there are other similar arcs as well: the rise and fall of Anne Boleyn in books one and two, the fall and rise of Stephen Gardiner, Bishop of Winchester, the rise and rise of Cromwell’s protegé, Thomas Wriothesley (‘Call-Me Risley’), and the great ascent from country gentry to royal in-laws of the Seymour brothers, Edward and Thomas. Throughout the novels and the television series there is a strong distinction made between a family of ancient lineage, such as that of Thomas Howard, who is confident that his line will endure no matter what the temporary ups and downs of court life bring him—and for the most part, despite a century of executions and attainders awaiting his family, he is correct, and the dukes of Norfolk remain today at the top of the British peerage. Less certain is the fate that awaits those families of ‘newer blood’ who are raised up by Henry VIII: Cromwell’s son survives his father’s downfall and execution in 1540 and retains his barony which is then passed down through generations of Cromwells before it becomes extinct in 1687. Wriothesley continues to prosper in Tudor service and is created Earl of Southampton at the start of the reign of Edward VI (1547). His heirs remain at the top of the court society until this earldom also becomes extinct in 1667. Of this collection of ‘new men’ at the Tudor court, the one that surpasses both of these in terms of longevity is—after a setback of over a century—the Seymours, dukes of Somerset.

The Seymours of Wolf Hall are mostly associated with Wiltshire, the flat and fertile county in the West Country where Henry VIII goes hunting at the end of the book Wolf Hall and discovers his blushing beauty Jane. Though Wolf Hall no longer remains in Seymour hands, their main ducal seat today, Bradley House, is also in Wiltshire. They also held significant lands in the neighbouring county of Somerset (hence perhaps the choice of title for the dukedom), and for a time were based in Devon (at Berry Pomeroy Castle and Stover House). But before any of this, the Seymours came from Monmouthshire in South Wales.

Like so many families of the English aristocracy who wanted to rise at court, having Norman ancestry was of paramount importance, even if you had to fudge it a bit. The later Seymours claimed their name was a corruption of the name St Maur, derived from a village of that name in Normandy near Avranches (though there are several towns in France named for the sixth-century Benedictine monk Saint Maurus). There was indeed a prominent family of that name who settled in Somerset and Wiltshire in the eleventh century and were created Baron St Maur in 1314—they had a different coat of arms to the family that gave rise to the Seymours, but that doesn’t necessarily mean anything, since heraldry was adopted after many Norman family lines had already split. The Barons St Maur died out in 1409 and their barony passed to the La Zouche family. Their possible relation was William St Maur who lived in Monmouthshire in 1240. His seat was Penhow (where the parish church is named for St Maur), a manor house later built into a castle by Roger de St Maur in the early twelfth century. It passed out of the family in 1359, but just in time to be surpassed by an even grander estate, that of the Beauchamp family in Somerset.

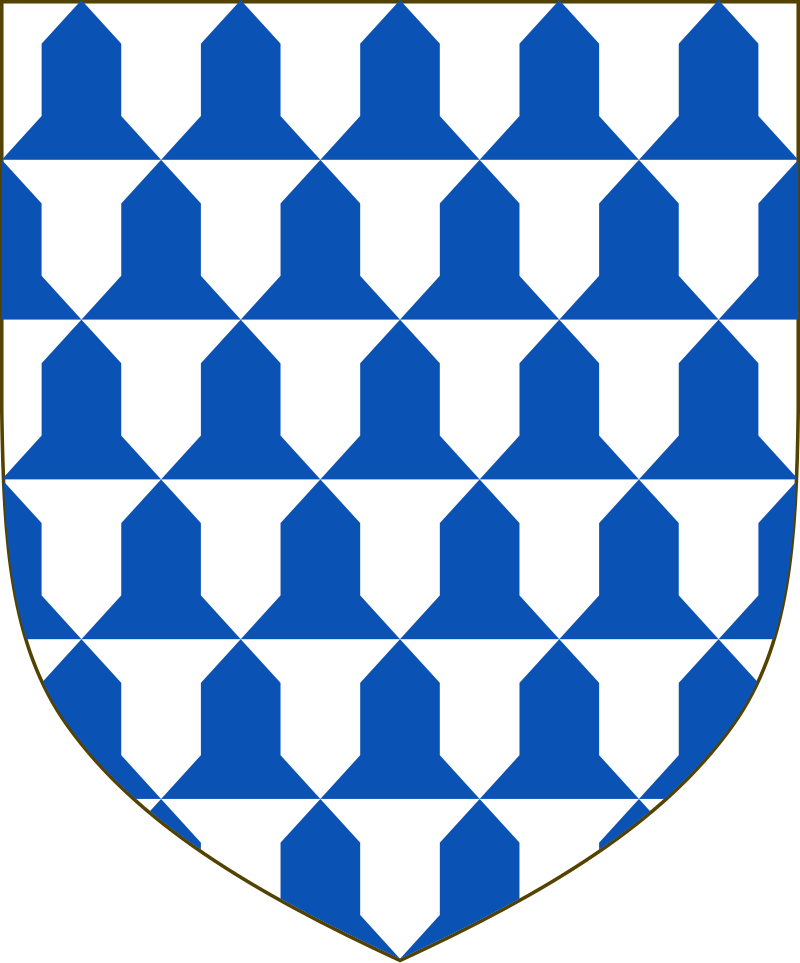

The Barons Beauchamp, of Hatch or Hache in Somerset, were one of the most prominent Norman families in the West Country. Their chief estate was part of a royal hunting forest granted shortly after the conquest of 1066 (a ‘hache’ is a Saxon word for a gateway into the forest). Several branches of the Beauchamp family—whose name means ‘beautiful field’ in French—spread across southern England: aside from the branch in Somerset, the line in Bedfordshire (Bletsoe) ultimately joined with the Beauforts (the family of the mother of Henry VII), while that of Warwickshire became the powerful earls of Warwick of the thirteenth to fifteenth centuries—much of their land and titles ultimately passed to another ‘new’ family of the Tudor era, rivals of the Seymours, the Dudleys. The Beauchamps of Hatch had a very simple yet distinctive coat of arms, an alternating pattern of blue and white known as ‘vair’, or squirrel’s fur. It is thought, by the way, that Cinderella’s glass slipper was not in fact verre (glass) in the original French version of the story, but vair, a more sensible material out of which to make shoes…

The Somerset Beauchamps were invited to Parliament as barons in 1299, but they died out in the 1360s—the peerage went into abeyance and has stayed there evermore, despite attempts to revive it. But the feudal barony (different from a peerage) passed to Cecily de Beauchamp, wife of Sir Roger de St Maur (or Seymour as he started to spell it by the 1390s). The Beauchamp name and distinctive arms will re-appear later in the Seymour history, notably as Viscount Beauchamp. Hatch itself passed out of the Seymour family in the 1670s; the house was torn down and replaced, then sold to another family again.

But the Seymours still maintained a residence in South Wales: the manor of Undy (Woundy or Gwndy), in Monmouthshire, which remained their main seat until the early 1400s when they moved to Wolf Hall in Wiltshire.

Another Roger Seymour, Speaker of the House of Commons, married Maud Esturmy, heiress in 1427 of the manor of Wulfhall in Savernake Forest, southeast of Marlborough. Savernake was a royal forest, granted to Maud’s father Sir William Esturmy—it is still privately owned (the only ancient forest in England still in private hands) by the Bruce family, whom we’ll encounter below. It is likely this is the forest in which Henry VIII was hunting when he met Jane. There was a large manor house at Wulfhall in the 1530s, with towers, which was mostly in ruins by the 1570s when the family moved to nearby Totnam (see below). The remains of the house continued to be used by servants, and evolved into a more modest farmhouse, leased out to tenants (and with a newer Georgian wing and a Victorian façade)—but recent archaeological digs have revealed some of the splendours of the original Wolf Hall, notably in tunnels underground.

Roger and Maud’s son John became Hereditary Warden of Savernake Forest, and Sheriff of Wiltshire, as was his son, also called John. Three more Johns followed as eldest son, until the last one died young, leaving his brother Edward as new head of the family. Edward’s mother, Margery Wentworth, had a drop of Plantagenet blood in her veins (via the Cliffords, Percys and Mortimers), which thus entered the Seymour bloodline. Closer to hand, she also shared blood with her half first cousins, Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk, and Elizabeth Boleyn, mother of Queen Anne. So young Edward Seymour was not without connections when he entered life at the court of Henry VIII. Sir John Seymour had served Henry VII and Henry VIII in various military campaigns and was named Sheriff and Justice of the Peace for Wiltshire, and notably, Constable of Bristol Castle in 1509. He was thus able to use his service and his wife’s connections to get his son Edward a place in the entourage of Princess Mary when she married King Louis XII of France in 1514—and his rise at court started from there.

Edward Seymour served with Henry VIII on his campaigns in France in 1523 and in 1529 was named esquire of the body and became one of the King’s favoured companions. He invited the King hunting at Wulfhall during a royal progress in 1535, and secured the King’s interest in his sister Jane. But Jane and her sister Elizabeth had already been living at court, as maids of honour to Queen Katherine of Aragon by at least 1532, and later in the household of Queen Anne Boleyn, whom she supplanted in May 1536—betrothed to the King only a day after Anne’s execution. Edward Seymour was raised to the peerage as Viscount Beauchamp. Just over a year later, in October 1537, Jane gave birth to Prince Edward—a Tudor heir at last!—and her brother Edward was promoted again, to Earl of Hertford.

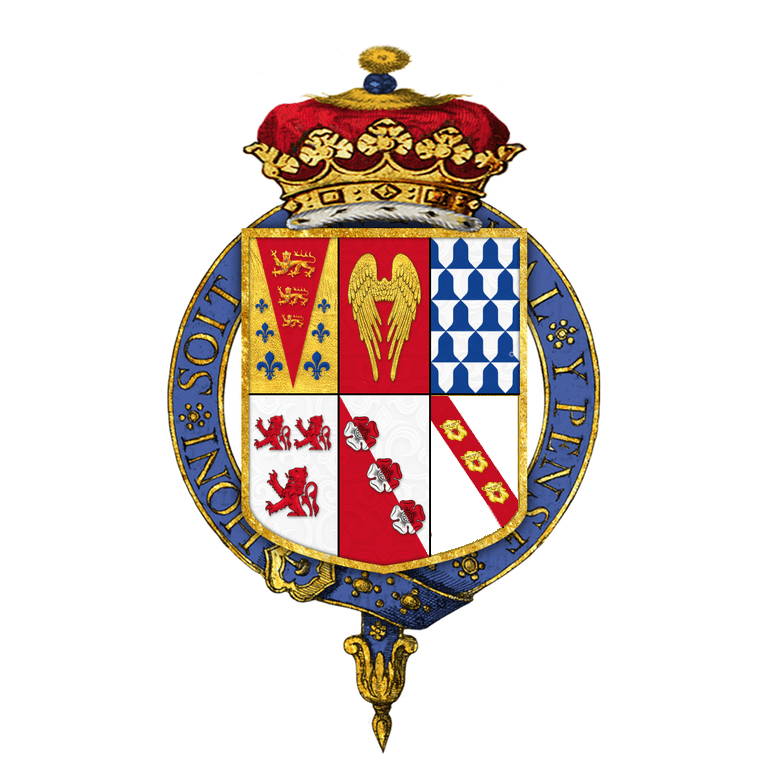

The Seymour arms was considerably augmented at this time as well—with a new element derived from the English royal arms, something we don’t see very often in English heraldry (the Howards being another example). In addition to their quite distinctive two golden wings on red, we now see a dramatic design whereby a field of blue fleurs-de-lys on gold (a reversal of the French royal arms) is divided by three gold English lions on red. The new Earl’s arms also included Beauchamp of Hatch on the top row, and below this the other families whose lands and pretensions he had inherited: Esturmy, MacWilliams and Coker.

Sadly Queen Jane died about a week after giving birth to Prince Edward. The Earl of Hertford managed to retain the King’s favour, however, and as uncle to the future king, was in a good position. Seymour’s greatest skill was as a military commander, and he effectively led campaigns against the Scots and the French in 1544-46. He returned from France as a hero in late 1546 and attended the King in his last months, then was named one of sixteen executors of the King’s will and guardians of the realm when Henry VIII died in late January 1547. Within days, Seymour had superseded the terms of the will and declared himself head of the regency council, and on 4 February was named Lord Protector of the Realm in the name of his little nephew, now King Edward VI. Hertford was also raised in the peerage once more: as Duke of Somerset, still an extremely rare title in England.

The regime of Lord Protector Somerset solidified the shift of power at court in favour of the Protestant faction. The Catholic Howards and Stephen Gardiner, Bishop of Winchester, were now out. Titles were given to Somerset’s allies, Wriothesley (Earl of Southampton) and Dudley (Earl of Warwick), and Somerset’s brother Thomas (created Baron Seymour of Sudeley and Lord High Admiral). There was another Seymour brother, Henry, but although he too had previously held some positions at court (notably in the households of queens Anne of Cleves and Katherine Parr), he preferred to remain in the countryside working as an administrator for the Crown—and he notably survived the tumults of the next decade and died much later.

Sudeley Castle has an ancient an interesting history, with royal roots back into the Anglo-Saxon period, and though most famous today as the resting place for Queen Katherine Parr, it was only a Seymour property for a few years. Most of its story belongs on a future blog post for the Brydges family, dukes of Chandos, who held it for about two centuries. It had been a royal property since the 1470s, granted by young Edward VI to Thomas Seymour in 1547, along with his new wife, the Dowager Queen, Katherine Parr. It returned to Crown ownership in 1553 then was given to Baron Chandos. Mostly ruins by the end of the eighteenth century it was partly restored by the Dent-Brocklehursts in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries who still live there today.

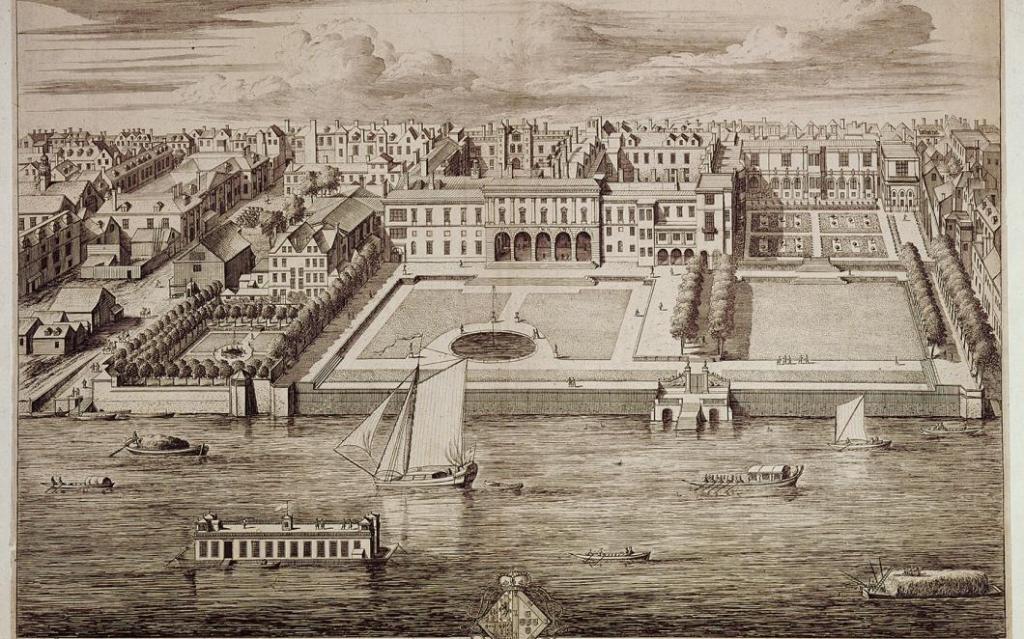

Meanwhile, the Duke of Somerset needed a London base. He had acquired a plot of land in 1539 in the area between the cities of London and Westminster, with one side facing the Thames and one side facing the old connecting road known as the Strand (for the old word for a river embankment). Now he began to build a new palace, Somerset House, importing newly fashionable architectural styles from the Continent. It was hardly started when it was confiscated by the Crown and from then on housed various members of the royal family, usually women: from Princess Elizabeth in the 1550s, and three Stuart consorts in the seventeenth century, Anne of Denmark, Henrietta Maria of France, and Catherine of Braganza. From 1775 it was completely rebuilt as a space for government offices and learned societies: the Royal Academy was here until the 1830s, and the Inland Revenue was based here until 2013. Since the 1990s Somerset House has been transformed into an arts centre, housing the Courtauld Institute and various independent creative businesses.

The 1st Duke of Somerset remained a strong military leader, soundly defeating the Scots at Pinkie in September 1547. But cracks in his administration appeared almost immediately, mostly via the ambitions of his friend Dudley and his brother Thomas, who wanted the position of governor of the young King and was jealous of his older brother’s power. He and his new wife Katherine Parr were already looking after her step-daughter and ward, Princess Elizabeth; and when Katherine died in September 1548, Thomas began to make noises about marrying Elizabeth himself—a future king-consort if Edward died, or at least royal brother-in-law (as well as royal uncle). This bold ambition was too much for the Lord Protector and other members of the Council, and in January 1549, he was arrested on charges of embezzlement and was beheaded in March.

Other opposition to Somerset’s rule came from various quarters. His desire to impose Protestant unity on the people of England, via the Act of Uniformity, 1549, and the Book of Common Prayer, annoyed those still faithful to the old church, mostly in rural communities. These were further angered by his reforms to landholding policies that allowed landowners to encroach on common lands. He also raised taxes to pay for the expensive ongoing war with Scotland. Two major rebellions were sparked, in the south and the east, which ultimately led to the financial ruin of the realm and the downfall of Protector Somerset’s regime. He was arrested in October 1549, and though he was soon released, he was replaced as head of the Regency Council by Robert Dudley, Earl of Warwick. In October 1551, Somerset was arrested again and sent to the Tower for treason (on vague charges), then was executed in January 1552 on charges of trying to usurp government back from Dudley (now Duke of Northumberland). Just over fifteen years after the triumph of the marriage of Jane Seymour to Henry VIII, the Seymour dynasty seemed finished.

And the dangers were not completely over. The 1st Duke of Somerset had had two sons by his first wife, John and Edward. Both had been disinherited back in 1540 when their father suspected their mother of infidelity. It wasn’t a full disinheritance though, but a curious ‘postponement’ of their rights to a succession (including, ultimately, the ducal title) to a position after the sons of Somerset’s second marriage. John had tried to fight back and sued for his mother’s succession, but it had been sold, so he was compensated with a new estate, Maiden Bradley, about which more later. Despite being semi-bastardised, the two older boys were arrested alongside their father in 1551—John died in the Tower in 1552, but Edward survived and formed a separate Seymour line in Devon, to which we will return.

The immediate successors to the 1st Duke of Somerset thus came from his second marriage. A second Edward (known as Lord Hertford as his father’s heir) had been educated alongside his cousin Edward VI. After his father’s execution, he was at first barred from succeeding to any lands or titles, but later some lands were restored by the young King. In 1559, Princess Elizabeth became Queen Elizabeth I and raised Seymour (now age 20) to the peerage once more as Earl of Hertford and Baron Beauchamp of Hatch. But just one year later he took a great risk by marrying in secret the Queen’s cousin and potential heir: Lady Catherine Grey, sister of the executed Jane Grey and granddaughter of Henry VII’s daughter Princess Mary. Although Mary was younger than Margaret, Queen of Scots, the terms of Henry VIII’s will favoured her descendants, the Greys, over the Stuarts, making Catherine Grey the heir. When the Queen discovered this marriage—due to Catherine’s evident pregnancy—she confined both in the Tower, where Catherine gave birth to a son, another Edward. The marriage was declared invalid and the son illegitimate. Somehow they managed to have more children in the Tower, then Catherine died in 1568 and Hertford was released. By 1576 he seemed to be in favour, as he was noted as carrying the Great Sword of State in formal processions at court.

In about 1575, the Earl of Hertford moved his seat from Wulfhall to a new house nearby: Tottenham or Totnam Lodge in Savernake Forest. This house would be enlarged in the 1670s by the 4th Duke of Somerset, who also redesigned the deer park. He bequeathed it to his niece Elizabeth who took it by marriage to the Bruce family. The Bruces, earls of Elgin and Ailesbury, rebuilt Tottenham in grand Palladian style in the 1720s, and it remained their seat until 1946. Since then it has been a school, then was empty for several years until it was sold in 2014 into private hands.

In 1582, the Earl of Hertford married again, and again secretly. This time it was Lady Frances Howard, daughter of Baron Howard of Effingham. He tried to set her aside in 1595 in order to legitimise his sons from his first marriage to Catherine Grey—and maybe claim their place in the line of succession since Elizabeth I still had not named an heir. Frances Howard died in 1598 and Edward Seymour married Frances Howard…yes, this is confusing. This Frances was daughter of a younger son of the Duke of Norfolk, and widow of a wealthy wine merchant, Henry Pranell. The death of Elizabeth I in 1603 meant it was finally Hertford’s time to shine at court—he and his wife were in great favour with the new sovereigns, James I and Anna of Denmark (despite, or maybe because of, his sons’ potential better claims to the English throne according to the terms of Henry VIII’s will?). He’s sent on diplomatic missions and she forms part of the Queen’s inner circle. In order to reside closer to court, Hertford bought an estate on the coast of Hampshire, Netley Abbey, in 1602. He also maintained a townhouse in London, Hertford House, on Canon Row, in Westminster (where today’s modern police station sits).

Netley Abbey was a Cistercian foundation, built in the 1230s, just outside Southampton. In 1536, it was seized and given to William Paulet, later Marquis of Winchester, who transformed it into a country house. His heirs sold it in 1602 to Hertford, and the Seymours lived here until it passed to the Bruce family as with so much else of the Seymour estates. They sold it right away to the Duke of Beaufort, but it quickly fell into disrepair and was mostly demolished—the remains of the ancient church buildings became a famous ruin. Since 1922 it has been run by the state and is today part of English Heritage.

When the Earl of Hertford died in 1621 he was buried in the Seymour Chapel in Salisbury Cathedral (other family members were buried in the parish church close to Wulfhall, in Great Bedwyn). His widow maintained her great royal favour and married the King’s cousin, the Duke of Lennox. The eldest son of Catherine Grey, Edward, called Lord Beauchamp once his legitimacy was recognised, had died before his father, as indeed had his own first son, Edward. So the succession passed to the second son, William, 2nd Earl of Hertford.

Trouble seems to follow this family around … so in 1610 when he was 22 years old, and still only the second grandson, William secretly married the one person he really shouldn’t: Lady Arbella Stuart. She was then considered fourth in line to the throne—as a descendant of Margaret Tudor—and had been the subject of plots and counterplots her entire life. William Seymour would himself have been considered seventh in line, so their marriage was a definite challenge to the legitimacy of the succession of James VI of Scotland to the English throne. Both were confined to the Tower of London—they escaped in 1611, though she was recaptured and died four years later in confinement; he fled abroad to the Low Countries.

But by 1616 Seymour was back at court and was knighted—so I guess all was forgiven. In 1621, he succeeded his grandfather as 2nd Earl of Hertford and took up his seat in the House of Lords—he was a continual opponent of his cousin King Charles I until about 1640, when politics got too radical and he was wooed into the royalist camp by means of his elevation in rank to Marquess of Hertford in 1641. During the Civil War he remained a moderate royalist and tried to keep open lines of communication through his brother-in-law, the Earl of Essex, a parliamentary commander. Hertford’s loyalty to the King was proven in the years following Charles I’s captivity—unlike other moderate royalists, he stayed with his cousin until his execution. He then retreated from London and laid low during the Commonwealth. In 1660, the Marquess of Hertford’s loyalty was rewarded and he was restored—finally—to his great-grandfather’s dukedom of Somerset. But his joy was extremely brief, enjoying the title for only a month before he died in October.

Another royalist commander in the Civil War was Francis Seymour, the 1st Marquess of Hertford’s younger brother, who was created Baron Seymour of Trowbridge (Wiltshire) in 1641. Like his older brother, he too had not always been a supporter of the King: elected as a Member of Parliament for Wiltshire in 1621, he was consistently opposed to the King’s plans to raise money for foreign wars. His seat in Parliament represented the Wiltshire town of Marlborough where he acquired Marlborough Castle, an old Norman motte and bailey that had been used for centuries as a dower property for English queens, but had been a ruin since about 1400. Francis built a new house here, which was later replaced by a larger building (1680s) by the 6th Duke of Somerset. By the late eighteenth century Marlborough Castle had been sold and became the Castle Inn with a prominent gentleman’s club; by the 1840s, this became the nucleus of the new Marlborough College, which it still is today.

The 2nd Duke of Somerset’s eldest sons had died in their twenties; the third, Henry, Lord Beauchamp, spent several months in the Tower (now a pretty familiar place for the Seymours) in 1651, and died only a few years later, meaning the succession in late 1660 passed to the restored Duke’s grandson, William, who was only eight (though his birth date seems to vary between 1650 and 1654). The new 3rd Duke was looked after by his mother, the very intelligent Mary Capell—later more famous as the 1st Duchess of Beaufort. This is where matters could be confusing, as the Beaufort surname was Somerset, and their ancestral title had been Duke of Somerset, as seen in their own separate blog. So in this case her new surname was Somerset, while her son’s title was Somerset.

Little William died in 1671, about twenty, and the succession passed to his uncle John, 4th Duke of Somerset—himself only about 25, but already the black sheep of the family, with a mountain of debts. His situation was not improved by the fact that most of the Seymour lands were not specifically entailed with the titles, so although he became a duke, his niece Elizabeth (the 3rd Duke’s little sister), inherited most of the estates: Wulfhall, Tottenham and Savernake Forest in Wiltshire; Hatch Beauchamp in Somerset, and, technically, the claim to the throne of England, by now fairly distant and forgotten. The 4th Duke died three years later in 1675, and a year later Elizabeth married Thomas Bruce, Lord Kinloss, son of the Earl of Ailesbury—his family were descended from the royal house of Bruce in Scotland, and in some minds, passed along the Grey-Seymour claim to the English throne to their descendants (today it is Teresa Freeman-Grenville, 13th Lady Kinloss).

The new Duke of Somerset in 1675 was thus a cousin, Francis Seymour, 3rd Baron Seymour of Trowbridge, of Marlborough Castle. But the 5th Duke too had a very short tenure, and was killed, aged 20, on the Ligurian Coast, where he duelled with a man whose wife he had insulted. The succession passed to his brother Charles, who in remarkable contrast, enjoyed a long and prosperous life. So enamoured was he with his semi-royal descent and so passionate about the details of court etiquette, that he gained the nickname ‘the Proud Duke’. But since the Seymour inheritance had passed to the Bruce family, he had to marry well, and marry well he did: Lady Elizabeth Percy was the heiress of the vast fortune of the earls of Northumberland, one of the oldest and grandest noble families in all of England. Though she was only fifteen, this was already her third marriage! Her father having died when she was three, Elizabeth was already owner of Alnwick Castle in Northumberland, Petworth Castle in Sussex, Syon House outside of London, and a number of other castles and properties in Cumberland and Yorkshire. A separate blog about the Percys of Northumberland will look more closely at these estates.

Immediately, the 6th Duke’s career took off as a member of the household of Charles II—but he fell from favour under James II and was dismissed as a Lord of Bedchamber in 1687. He spent the next few years rebuilding Petworth into a monumental ducal palace, in French château style, worthy of the double dynastic identity of Seymours and Percys (as an aside, his marriage contract said he was to change his name to Percy, but he never did). It was the Duchess of Somerset who helped restore her husband’s position at court, as a favourite of Queen Anne. The Duke became Anne’s Master of the Horse in 1702, and his wife eventually replaced the Duchess of Marlborough as Mistress of the Robes and chief confidante. Their proximity to the Queen played a key role at the very end of her life when she began to waver on her commitment to the Hanoverian Succession (perhaps preferring to atone for supporting the rebellion against her father back in 1689); Somerset and other key peers kept her on target. Under George I, the Duke at first retained his post of Master of the Horse, but was dismissed in 1715, and retired to private life. Elizabeth Percy died in 1722, and after a strange unrequited love affair with the Duchess of Marlborough, Somerset married the much younger Lady Charlotte Finch. He died over two decades later in 1748 at his beloved Petworth.

There was only one surviving son, Algernon (a traditional Percy name), who had had a fairly successful career under his courtesy title, ‘Earl of Hertford’. After 1722, he became Baron Percy, as his mother’s heir. He held a succession of administrative posts, from governor of Tynemouth Castle in Northumberland in 1711 to governor of Minorca, 1727, and of Guernsey, 1742. He was also Lord Lieutenant of Sussex as heir apparent to Petworth. But when he succeeded as 7th Duke of Somerset in 1748, he had already lost his own son, George, Lord Beauchamp, and disliked the idea of his estates passing to a very distant Seymour cousin. So in 1749 there was an extraordinary set of titles created for him by George II designed to favour two different heirs. The Duke was created Earl of Northumberland with a special remainder for his daughter Elizabeth and her husband Hugh Smithson (who changed his name to Percy, and ultimately became 1st Duke of Northumberland). He was also created Earl of Egremont, named for the Percy estates in Cumberland, with a special remainder for his sister’s son, Charles Wyndham—the Wyndhams inherited Petworth and they still live there today. The 7th Duke of Somerset died only one year later in 1750.

So once again, the next duke of Somerset inherited the title but very little else.

In order to find the 8th Duke of Somerset, we need to jump all the way back to the mid-sixteenth century and to the younger of the two disinherited sons of the 1st Duke: Sir Edward Seymour, Lord of Berry Pomeroy. The castle of Berry Pomeroy, near Totnes in south Devon, was built on an outcrop overlooking a narrow valley by the Pomeroy family in the late fifteenth century (on the site of a much older manor). That family fell onto hard times and sold the manor and castle to Lord Protector Edward Seymour in 1547. His son Edward, disinherited from the Wiltshire estates, was given this instead; he built a new Tudor mansion on the site in the 1560s—huge, with four storeys and dozens of rooms. In 1583, Elizabeth I named him High Sheriff of Devon thus more firmly establishing his branch of the family in the southwest of England. His son Edward was then given the rank of baronet in 1611 by King James. The 2nd baronet (another Edward) was the governor of Dartmouth (the main port of south Devon) and as a royalist, was imprisoned in London during the Civil War. The house at Berry Pomeroy was abandoned and fell into ruin—mostly demolished in the 1690s. Yet it was given a new lease on life in the more romantic age of the early nineteenth century, when Regency era tourists developed a passion for ancient ruins. Numerous engravings and paintings followed, and gothic novels set in the castle, and in 1830—seeing a good thing—the Seymours engaged in one of the first examples of ‘heritage conservation’, hoping to draw more tourists and earn some money in local hotels and pubs.

The reason for the house’s abandonment was the successful political career of the 4th Baronet, Edward Seymour, who wished to live closer to London once he became Speaker of the House of Commons in 1673, and Treasurer of the Navy. He based himself at Bradley House on western edge of Wiltshire near the border with Somerset, not far from the more famous country houses of Stourhead and Longleat. The village is called Maiden Bradley and was said to have taken this name from a daughter (a ‘maiden’) of an official of King Henry II who suffered from leprosy and founded a hospital in the village of Bradley in 1164. This later became an Augustinian priory, and when the priories were dissolved, this one was given to Edward Seymour in the 1530s, then passed to his eldest sons of the Berry Pomeroy line. A new house was built in the 1690s (it is said using materials from Pomeroy). It thus became the ducal seat when this branch succeeded in the 1750s, and remains so today. Much of it was dismantled in the 1820s, leaving just one wing. It remains mostly shut for visitors.

The 4th Baronet’s career continued to rise—in the House of Commons he led a powerful faction (then developing into the Tory Party) that opposed the exclusion of James, Duke of York, from succeeding to the throne; yet he was also one of the first to abandon James in November 1688 and declare for William of Orange in his invasion of England—at Brixham in Devon, quite close to Berry Pomeroy. After he retired from Parliament, he was given the prominent court position of Comptroller of the Royal Household by Queen Anne in 1702.

Sir Edward Seymour married twice—his second wife was a Popham, co-heiress of even more estates in Wiltshire (Littlecote); and his son by his first marriage married a Popham too, to secure the inheritance—as indeed did a younger grandson, to be sure (ultimately founding a separate line, of Knoyle House, Wiltshire; extinct in 1888). The oldest grandson, rather remarkably, succeeded his very distant cousin in 1750 to the Dukedom of Somerset, so we’ll follow his line below. His uncles, the two sons of the 4th Baronet’s second marriage, instead picked up the succession of another gentry family, the Conways of Warwickshire (with the very brief title, earl of Conway), who also had significant lands in Ireland—a factor which shaped their political fortunes. The elder of these, Popham Seymour-Conway, was killed in a duel in 1699, leaving the estates to his brother, Francis, who was created Baron Conway of Ragley in 1703—but also Baron Conway of Killultagh (Antrim) in 1712, ensuring he had a voice in both English and Irish parliaments. He was also given a seat on the Irish Privy Council. His two sons founded the junior branch of the House of Seymour, the Seymour-Conways. The younger of these, Henry, was a politician and soldier, holding the post of Chief Secretary for Ireland, 1755-57, and Speaker of the House of Commons, 1765-68, and rising in the army to Commander in Chief of the Forces, 1782-93. The older brother, Francis Seymour-Conway, was restored to the old earldom of Hertford, 1750—the same year as his cousin’s succession to the dukedom of Somerset—and was sent to Ireland as its viceroy in 1765-66, then returned to England to serve as Lord Chamberlain at court for nearly twenty years. At the end of his life he was raised a rank to Marquess of Hertford (1793).

Today’s Marquess of Hertford is the 9th (Harry Seymour—they dropped Conway from the name in 1870—born in 1958). The other main legacy of the Marquesses of Hertford—incidentally a much wealthier and much more aristocratic family than their senior cousins the dukes of Somerset—is the splendid Wallace Collection in London, based in Hertford House and housing artworks amassed mostly by the 3rd and 4th marquesses and willed to the latter’s illegitimate son, Richard Wallace, then to the nation in 1897.

Ragley Hall, west of Stratford-upon-Avon, Warwickshire, was built by the Earl of Conway in 1680. It has remained the seat of the Seymour-Conway family since then; in the 1950s it was refurbished and opened to the public. In the 1750s, the family bought a second seat, Sudbourne Hall in Suffolk. Richard Wallace purchased it from the Marquess of Hertford in 1871, then sold it in 1884—it passed through various hands until it was demolished in 1953.

Returning to the main line of the Seymours, who seem to be quite good at keeping their line going (and the ducal title), when other similar clans did not, we see yet another Edward Seymour becoming 8th Duke of Somerset in 1750 (having been merely a baronet). He inherited none of the vast estates, now given to the Smithsons and the Wyndhams, and died only seven years later.

The 9th Duke of Somerset, also Edward—about whom there seems to be nothing to say—died unmarried in 1792, so the titles passed to his brother Webb (his mother’s maiden name), the 10th Duke—but only from January 1792 to December 1793 (at nearly 80). His son Edward Adolphus, the 11th Duke, formally changed the spelling of his surname to St Maur (pronounced ‘seemer’), believing it to reflect the original spelling, and picking up on the air of the neogothic and romantic love of all things medieval—it was he who commissioned the restoration (and marketing) of Berry Pomeroy as a tourist attraction in the 1830s.

The 11th Duke moved his seat closer to the ruin in Devon by acquiring a new residence, Stover House, in Teigngrace, near Newton Abbot. Purchased in 1829, the Georgian mansion had been built by the Templer family in the 1770s (originally merchants from Exeter). They had also constructed a nearby church and the Stover Canal. The Duke of Somerset added a large porte-cochère, or covered gateway for coaches, a clock house and stables. He was a scholar, a mathematician and President of the Royal Institution, 1826-42. In 1808 he purchased a London townhouse on Park Lane in Mayfair, which he named Somerset House, despite there already being a more famous building of this name (see above). He married Lady Charlotte Hamilton an heiress of the 9th Duke of Hamilton, and filled Stover House with her renowned art collection.

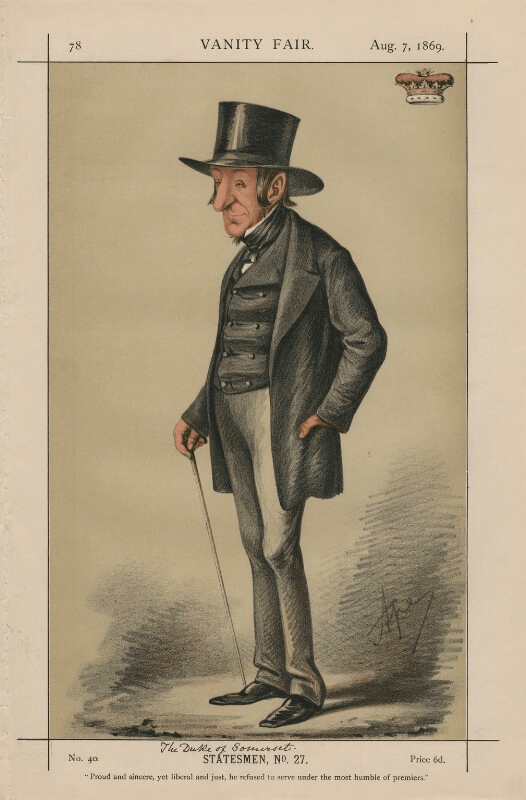

The 11th Duke’s son Edward Augustus became 12th Duke in 1855. As a younger man, he had married beneath his station, to Georgiana Sheridan, granddaughter of the playwright, and a famous society beauty. As heir he held various posts in the Whig governments of the 1830s-40s, then as Duke he served as First Lord of the Admiralty, 1859-66. He was also honoured with a new title, Earl St Maur, of Berry Pomeroy, in 1863—this was done to ensure his son had a proper courtesy title as the son of a duke (since the earldom of Hertford had not passed from the 7th to the 8th Duke back in 1750). His son Edward Augustus (but known as Ferdinand) did use this as his courtesy title, but was also created ‘Baron Seymour’ in a writ of acceleration (also 1863) to allow him to take up his seat in the House of Lords. He led a fairly romantic and wild life as a soldier in India and in Italy, where he became the subject of a scandalous trial where he was accused of horsewhipping a fellow soldier. Some gossipy sources say he went crazy, or that he converted to Islam. Earl St Maur may or may not have secretly married in Tangier in about 1862, then died in England in 1869 after a botched operation, leaving an illegitimate son, Harold St Maur. A younger son, also called Edward, was a diplomat, and was killed by a bear in India in 1865.

The 12th Duke of Somerset, now heirless, despised his brothers who had so looked down on his wife socially, so he arranged to pass Stover House and its art collection to his illegitimate grandson, Harold, while the rest of the inheritance was divided amongst his daughters (for example, one of the daughters inherited Somerset House on Park Lane, which she soon sold—today the site is occupied by the Marriott Hotel Park Lane). When the Duke died in 1885, Harold did make an attempt to claim the dukedom, but failed (and tried again in 1923, again with no success). Stover House has been leased to a school since 1932.

So the 13th Duke of Somerset, Archibald, moved back to Maiden Bradley, now stripped of all its contents. He died unmarried a few years later and passed the titles to a third brother, Algernon, who died three years later. The Seymours/St Maurs certainly go through dukes quickly! The last duke of this line was Algernon, 15th Duke of Somerset, who lived quietly at Bradley House and died in 1923. The succession jumped once more across several generations of male-line kinship, to Col. Edward Seymour (and the more familiar surname was resumed).

Col. Edward Seymour was the great-great-grandson of Lord Francis Seymour, Dean of Wells Cathedral and Chaplain to George II, the third son of the 8th Duke of Somerset. The new 16th Duke of Somerset had been a career soldier, in army ordnance. It took two years for the House of Lords to give full approval to his succession to the ducal title (disputed by the Marquess of Hertford), and he died a few years later, in 1931. His son, Evelyn, though by no means one of the great landowners of Britain like his fellow dukes, was nonetheless honoured with the position of carrying the sceptre at the coronation of George VI in 1937, and appointed to one of his family’s longstanding posts, Lord Lieutenant of Wiltshire, 1942-1950. Like his father he had a long military career, serving in the Boer War, World War I and World War II. His son Percy, the 18th Duke from 1954, had also been a soldier, with service in Asia; when he died his title passed to his son John (we seem finally to have run out of Edwards), who worked as a chartered surveyor in the 1970s-80s, then sat in the lords as Duke from 1984 until the hereditary peerage was abolished; he was then selected as one of the elected peers in 2014. His heir is Sebastian, Lord Seymour. There may no longer be a Seymour of Wolf Hall, but the Wiltshire hills at Maiden Bradley are still home to this amazing survivor of a ducal dynasty.

(images Wikimedia Commons)

excellent. what a story. one question: when do you think consciousness of ‘norman blood’ , and the sense of being separate from ‘anglo-Saxons’ without it, died out? when did normans start marrying English? thanks Philip

LikeLike

Good question. I know they started marrying English right away but a medievalist would be better able to answer it. It is more complicated I think since a lot of English families Frenchified their names (like the original owners of Sudeley Castle were called ‘de Sudeley’ though descended from Wessex royalty). And I don’t think the sense died out, but in fact resurged (as it did in France) in the 18th/19th centuries. Seymour/St Maur is a perfect example.

LikeLike

kind! 17 2025 Seymour of Wolf Hall: the rise and fall and rise again of the dukes of Somerset remarkable

LikeLike

My line intersects with the Seymour line, and I am wondering if you have any information regarding the connection. My ancestors are the de Erleigh family, variously spelled de Erleigh, de Erlegh, de Erleia, de Earley, de Erley, d’Erley, de Herlegh in english records. The surname was taken from land ownership as a “place name” from the lands owned by the Erleigh family. These lands were recorded in the Domesday Survey of 1086. There were lands in the hundred of Sonning, Berkshire (modern-day town, spelled Earley) and lands in the hundred of Bath, Somerset (modern-day Warleigh), both called “Herlei” (Latin Spelling). The modern-day English surname we now know as Earle / Earles or Earl / Earls. John (Erleigh) de Erlegh (abt.1360-1409) of Beckington, Somerset, England married Isabel De Paveley (daughter of Sir John Paveley). This marriage produced only one daughter, Margaret Erleigh who was the sole heiress of the Erleigh lands and estate.

Margaret Erleigh married John Seymour (abt.1379-1415) in a first marriage, and they had one son, John Seymour (1408-1438).John Seymour (abt.1379-1415) was the second son of Richard Seymour (1345-1401) or Richard St. Maur (Richard de Sancto Mauro), the late lord of Castle Cary (Castelcary) in Devon, and John inherited from him the manor of North Molton, Devon. The son John Seymour (1408-1438) married Elizabeth Brooke daughter of Sir Thomas Brooke.

When John Seymour died, Margaret (Erleigh) Seymour married a second time to Walter Sandes (de Sondes) and they had a child named Margaret Sandes (de Sondes). This daughter Margaret was a half sister to John Seymour (1408-1438) who married Elizabeth Brooke. Margaret Sandes (de Sondes) married back into the Erleigh family. She married John Earle of Ashburton, County Devon. John Earle was in the Erleigh line through a “junior” branch. They were thought to possibly be 2nd cousins.John Earle and Margaret Sandes great grandson was named Walter Earle. This Walter Earle was a courtier and servant of the Royal Household in the time of Henry VIII.Walter was serving as a Page in November 1541 at the time of Catherine Howard’s downfall due to adultery. He retained a position at court after Catherine’s execution, having been transferred to the household of Edward Seymour KG (abt.1500-1552), Earl of Hertford (later 1st Duke of Somerset), the eldest brother of Queen Jane Seymour (abt.1509-1537), the third wife of Henry VIII.He may have been transferred to the household of Edward Seymour due to not being of full age at the death of his father. My line comes from a cousin branch in Collingbourne Kingston, Wiltshire. Collingbourne Kingston was just 4 miles from Wulf Lodge and was part of the Seymour holdings.Sorry this is long but I am hoping you might have some insight into how my Seymour intersection connects with the other Seymour lines.

LikeLike

Dear Glenn. This is fascinating! Sounds like you are already done so much of the research. The missing link appears to be in the very earliest generations of Seymours and how the Castle Cary branch links in. This is pretty far outside my specialism, and I usually pull my information from a website called Medieval Lands (which has a section on Seymour St Maur) or Stirnet.com, which is very complete, but often has a lot of errors. You need to register to use their site, but I suspect if you did and wrote to them they are connected to a lot of other genealogists who work in this area. I hope you find something!

LikeLike

My line intersects with the Seymour line, and I am wondering if you have any information regarding the connection. My ancestors are the de Erleigh family, variously spelled de Erleigh, de Erlegh, de Erleia, de Earley, de Erley, d’Erley, de Herlegh in english records. The surname was taken from land ownership as a “place name” from the lands owned by the Erleigh family. These lands were recorded in the Domesday Survey of 1086. There were lands in the hundred of Sonning, Berkshire (modern-day town, spelled Earley) and lands in the hundred of Bath, Somerset (modern-day Warleigh), both called “Herlei” (Latin Spelling). The modern-day English surname we now know as Earle / Earles or Earl / Earls. John (Erleigh) de Erlegh (abt.1360-1409) of Beckington, Somerset, England married Isabel De Paveley (daughter of Sir John Paveley). This marriage produced only one daughter, Margaret Erleigh who was the sole heiress of the Erleigh lands and estate.

Margaret Erleigh married John Seymour (abt.1379-1415) in a first marriage, and they had one son, John Seymour (1408-1438).John Seymour (abt.1379-1415) was the second son of Richard Seymour (1345-1401) or Richard St. Maur (Richard de Sancto Mauro), the late lord of Castle Cary (Castelcary) in Devon, and John inherited from him the manor of North Molton, Devon. The son John Seymour (1408-1438) married Elizabeth Brooke daughter of Sir Thomas Brooke.

When John Seymour died, Margaret (Erleigh) Seymour married a second time to Walter Sandes (de Sondes) and they had a child named Margaret Sandes (de Sondes). This daughter Margaret was a half sister to John Seymour (1408-1438) who married Elizabeth Brooke. Margaret Sandes (de Sondes) married back into the Erleigh family. She married John Earle of Ashburton, County Devon. John Earle was in the Erleigh line through a “junior” branch. They were thought to possibly be 2nd cousins.John Earle and Margaret Sandes great grandson was named Walter Earle. This Walter Earle was a courtier and servant of the Royal Household in the time of Henry VIII.Walter was serving as a Page in November 1541 at the time of Catherine Howard’s downfall due to adultery. He retained a position at court after Catherine’s execution, having been transferred to the household of Edward Seymour KG (abt.1500-1552), Earl of Hertford (later 1st Duke of Somerset), the eldest brother of Queen Jane Seymour (abt.1509-1537), the third wife of Henry VIII.He may have been transferred to the household of Edward Seymour due to not being of full age at the death of his father. My line comes from a cousin branch in Collingbourne Kingston, Wiltshire. Collingbourne Kingston was just 4 miles from Wulf Lodge and was part of the Seymour holdings.Sorry this is long but I am hoping you might have some insight into how my Seymour intersection connects with the other Seymour lines.

LikeLike