I was recently talking to some students about the character Captain von Trapp in the film ‘The Sound of Music’. Students are always curious how someone from a landlocked country like Austria could be a retired naval commander. We also got to talking about his rank, since he is called a baron in the film (and he is initially planning to marry a baroness). It led to an investigation of the term ‘ritter’, which was actually the real Georg von Trapp’s rank in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, akin to ‘baronet’ in the UK system, that is, a knighthood that is hereditary. So we chatted about rank and its place in aristocratic society and looked into his familial relations to see if he was connected to people of much higher rank at the Viennese court—and indeed, it turns out that he was, though almost entirely through the family of his first wife (the mother of all those singing children), Agathe Whitehead. Further research reveals that this Anglo-Austrian aristocrat was related to several families of princely rank, so is worth a look-in on this blogsite: a first cousin was married to a Prince Bismarck (son of the Iron Chancellor), while one of her aunts was married to the Duke of Ratibor and Prince of Corvey (from the hugely sprawling family of the princes of Hohenlohe), and another aunt was married to the Prince of Auersperg.

It is this last connection, Auersperg, that also allows us to look more closely at the area that was once the Von Trapp stomping grounds: Austria’s seacoast, known as the ‘Austrian Littoral’. Formed in 1849 from the old provinces of Istria, Görz/Gorizia and the city of Trieste, the Littoral is divided today between Italy, Croatia and Slovenia. It was a multi-ethnic area, called the Küstenland in German and Primorska by the Croats and Slovenes (just meaning ‘coastland’ in either language). This is where the Austro-Hungarian Navy was based, with its chief port in Pola (now Pula, Croatia), a naval academy in Fiume (now Rijeka) and shipbuilding facilities in Trieste. This is where most of Captain von Trapp’s wife’s money came from. Further inland was the province of Carniola, now (mostly) the Republic of Slovenia, where the Auersperg family ruled large estates for centuries, fairly independently of imperial rule in far-off Vienna. Their formal title here was Duke of Gottschee, which was the historic name for a small German-speaking enclave in what is now southeastern Slovenia. Since the Second World War, the area has been ‘ethnically cleansed’ and the area re-named Kočevsko (and its main town, Kočevje). The name initially referred to the local fir spruce or hvoja in Slovene.

So although the Von Trapps were not dukes or princes, this blog will look at their close cousins, the princes of Auersperg, dukes of Gottschee.

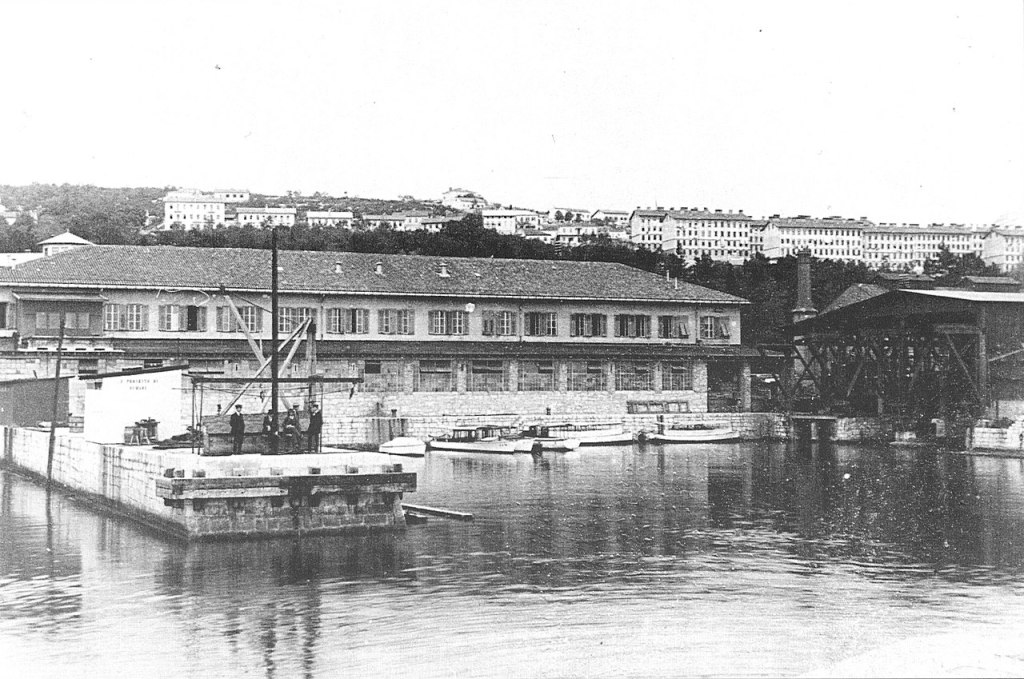

Let’s start though with Agathe Whitehead, the woman who does not appear in ‘The Sound of Music’. Her grandfather, Robert Whitehead, was an English engineer from Bolton who settled in Fiume in the 1850s and developed the first self-propelled torpedo. He soon constructed a large factory building torpedoes and ships for the Austro-Hungarian Navy, a business enterprise continued under his son John. When John died in 1902, most of this fortune passed to Agathe. Robert’s second son, Sir James Whitehead, was a diplomat, who eventually rose to the post of British envoy to the Kingdom of Serbia, 1906-10 (a pretty sensitive time to be in Belgrade); his son Edgar was also famous, a generation later, as Prime Minister of the British colony of Southern Rhodesia, 1958-62 (a pretty sensitive time to be in southern Africa!).

In 1911, Agathe married Georg Ritter von Trapp. Though his family originated in Hesse, in central Germany, he had been born in Zara, further down the Adriatic coast, which was briefly part of Italy after World War I so, oddly (considering the plot of ‘The Sound of Music’), he and his family were given Italian citizenship, but in 1947 it became part of Yugoslavia, and is now Zadar in Croatia. His father was also a naval captain, and had been elevated to the lowest rank of the Austrian nobility, ritter. They had a villa in Pola—in the centre of town, today divided into flats. With his marriage, Georg acquired the Whitehead villa in Fiume, built by Agathe’s grandfather on the Adriatic seafront in 1878, across the road from his factory, and a summer residence, Erlhof on Lake Zell in the Alps, south of Salzburg. Erlhof was a very old country house bought by Agathe’s grandmother in 1900—it has been run as a restaurant and hotel since the 1970s.

Agathe and the children spend World War I at Erlhof, while Georg became the most successful submarine commander. After 1918, Fiume and Pola became parts of the new Kingdom of the Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (after 1929 changed to Yugoslavia), so the von Trapps settled in Klosterneuburg, a suburb of Vienna, where their last child (of seven) was born. That year, five of these children caught scarlet fever, and, in nursing them, so did their mother, and she died of it in September 1922. Georg moved the family in 1924 to a new villa in Aigen, a posh suburb of Salzburg, across the river from the old town, where, in 1926, he hired a young nun as nanny, Maria Agatha Kutschera (whose family was, interestingly in the context of this blog about ethnically blended Austrians, actually Kučera, from Moravia). They married in 1927 and had three more children. In 1935, Georg invested much of his late wife’s fortune in an Austrian bank—it failed and he lost most of his income. This explains in part why the family turned to professional singing. As the political climate in Austria heated up in 1938, the Captain and Maria took their large family on a concert tour to the United States and did not return.

So let’s return to Agathe Whitehead’s other, non-English, family—and it makes you realise that those children dancing around in drapery in Salzburg were actually very well connected to very aristocratic cousins in Vienna (and does also invite the question of who was the character of Baroness Schraeder modelled on…a mysterious ‘Princess Yvonne’?). Agathe’s mother, married to an Englishman born in Austria, was herself a blend of Austrian and Hungarian nobility. Agathe von Breuner’s father was Count August Johann von Breuner-Enckevoirt, and her mother was Countess Agota Széchenyi de Sárvár-Felsővidék, one of the leading Hungarian magnate families. Both the Breuner and Széchenyi families produced powerful statesmen in the nineteenth century: István Széchenyi was one of the greatest champions of progress in Budapest, as in fact was Agathe’s great-grandfather, Count August von Breuner in Vienna, as a leader of the liberal opposition to the ultra-conservative regime of Prince Metternich in the 1840s. One of the Auersperg princes we will encounter below was a key ally (and in fact his son-in-law). Later in the century, the Breuners became extinct, and their lands and their name passed to a cadet branch of the House of Auersperg.

The Breuner family were minor nobles from Styria (the Austrian province south of Vienna, in the Alps). Different origin stories say they originated here or they migrated here from the Rhineland in the Middle Ages. But they were securely situated in Styria by the 1450s, with the lordships and castles of Stübing and Fladnitz. They split into two branches in the sixteenth century. The senior Styrian branch became counts in 1666 and went extinct in 1827. The junior branch moved to Lower Austria and were given the lordship of Staatz in the region north of Vienna, with a prominent castle on a round hilltop overlooking the plain that leads from Austria into Bohemia; this castle was destroyed in the Thirty Years War—and it remains a ruin today—but by then they had acquired the castle of Asparn, a few miles into the hills to the south, and made it their chief residence. Asparn was a much grander residence, owned for a while by the Habsburgs themselves—today it houses a museum of pre-history and medieval archaeology.

The Breuners were elevated to the rank of baron in 1550, then count in the 1620s. They were prominent in Austrian imperial and provincial government in this century, until the senior line (at Asparn) died out in 1716, and the junior line inherited the properties of the Enckevoirt family and added that name to their own. The most prominent member of the family in this period was Philipp Friedrich, Bishop of Vienna, 1639 to 1669, during which time he rebuilt much of the diocese following the Thirty Years War and in particular re-constructed the grand high altar in St. Stephen’s Church in Vienna.

Other built memorials of the Breuner family included a Palais Breuner in Graz for the senior branch, and a Palais Breuner in Vienna for the junior branch—acquired by Count August in 1853 (formerly the Neupauer Palais, built 1715 for Austria’s Lord High Chamberlain), on Singerstrasse, in the neighbourhood behind the Dom. Their country seat was Schloss Grafenegg in Lower Austria (inherited in 1813), originally built in the fifteenth century, which they rebuilt in the 1840s-50s as one of the best examples of romantic historicism in architecture. The castle, near the city of Krems on the Danube, remains a major tourist attraction and concert venue today. This branch of the family died out in 1894, and the Viennese palace and Grafenegg Castle passed to the co-heiress who had married the Duke of Ratibor-Corvey—they still own both today. The rest of the properties (and the name Breuner, though now with two n’s for some reason) passed to the Auerspergs.

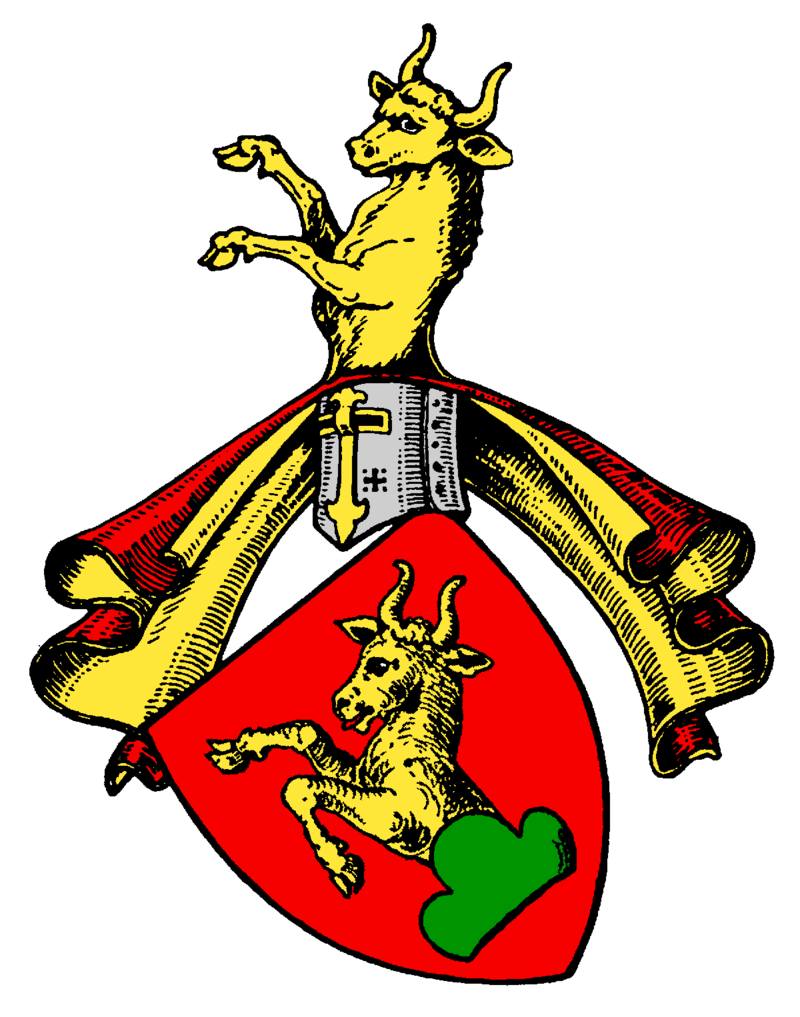

The Auersperg family took their name from a castle with an earlier form Ursperg, which may suggest it was named for the ancient mighty wild oxen, the aurochs, which survived in the wilds of eastern Europe until the end of the Middle Ages. The family coat of arms sports an ox’s head, as do the arms of several other Balkan families or states (like Moldavia).

The ancient triangular castle on a hilltop (the ‘berg’ or ‘perg’) has three towers, one of which is named the ‘Ox Tower’. The Slovene word for aurochs (or simply ‘aur’ in German) is ‘tur’, and the Slovene name for the castle is Grad Turjak (and the Auersperg family themselves are referred to locally as the Turjaški). The castle was built and rebuilt several times in the Middle Ages before the current mighty structure, from about 1220. Badly damaged in an earthquake of 1511, it was swiftly rebuilt and withstood and assault by Ottoman Turks in 1528.

Auersperg Castle dominates the valley of a river that flows north into the provincial capital of Ljubljana, today’s capital of Slovenia, but long known in German as Laibach, in the Austrian duchy of Carniola. This province takes its name from the indigenous ancient people here, the Carni, from which its German name, Krain, derives, though this sounds confusingly like the Slavic word for ‘border’, ‘krajina’, and a borderland indeed it was, between Slavs and later Germanic settlers, and between the Austrian realms and the ever-expanding Ottoman Empire to the southeast. The neighbouring province (and they are usually grouped together) is called the Windisch March, or ‘Slavic Border’ (Germans called Slavs Winds or Wends), which incidentally gave its name to another Austro-Slovene princely family, Windischgraetz, who will have their own blog post.

The Ursperg and later Auersperg family of knights defended this frontier for centuries. In the early Middle Ages they served the dukes of Carinthia (the duchy to the north) as chamberlains and marshals, then the Habsburgs in this same capacity once they took over Carinthia and Carniola in the 1330s. They divided into two main branches in the fifteenth century, with the senior line based in their castles of Schönberg and Seisenberg (today called Šumberk and Žužemberk in Slovene) and raised in rank to imperial baron (freiherr) in 1550. The lovely medieval castle of Seisenberg, on the Krka river southeast of Ljubljana, was rebuilt by the local bishop with seven great towers in the 1520s, then purchased by the Auerspergs in 1538. It became the family’s main residence in this region, and over the centuries they developed a significant ironworks industry here. All the family’s lands in Carniola were seized by the Yugoslav government in 1946, and have not been returned.

In the sixteenth century the House of Auersperg provided their Habsburg overlords with several able commanders, most famously Herbard VIII and Andreas, the ‘Carniolan Achilles’. Herbard (or Herward) was Military Governor of Carniola and Captain of the Croatian Frontier. He was also a Protestant and one of the leaders in implanting the reformed faith in this corner of the world; still today considered one of the heroes of Croatia and Slovenia. But in 1575 he took on the might of the Ottoman Empire at a battle in Croatia near Bihać (today’s border between Croatia and Bosnia) and was badly defeated—his head was severed and paraded in triumph back in Constantinople. Nearly two decades later, his cousin Andreas returned to this frontier as Commander-in-Chief of the Croatian Frontier and contributed to a significant defeat of the Turks at Sisak (1593), which effectively put a stop to Ottoman expansion over the River Sava—it was a dramatic victory, with the retreating Turks being forced to swim back across the river and many hundreds drowning.

It is worth noting again that these Auerspergs, like many members of the Austrian nobility, had joined the Protestant faith. Herbard’s father, Trajan, was an early supporter and protected a prominent Lutheran theologian in this region and supported his efforts to create the first translation of the Bible into Slovenian. Other Slovene books were printed here, one of the earliest efforts to bring a Slavic language to an equal footing with German.

In the seventeenth century, most of the Austrian high nobility converted back to Catholicism, and were rewarded by their Habsburg overlords. Two branches were established and raised to the rank of imperial count in 1630. The senior line retained the castle of Auersperg (until 1945) and continue to exist (the ‘comital branch’) today. Auersperg Castle was taken by Yugoslav Partisans in 1943 and badly damaged. Nationalised by the Communist regime that followed, it has only slowly been restored starting in the 1990s.

The junior line consisted of three brothers. The eldest, Wolfgang Engelbert, was a great collector of art and objects in his new grand residence in Ljubljana; he also acquired the County of Gottschee in 1641, the German speaking enclave in the hills of southern Carniola (as noted above) that would become a much more important part of the family’s story later on; its castle was rebuilt in the 1680s, and completely destroyed in World War II. The second brother Herward founded another line of counts (who died out in the early twentieth century); while the youngest brother, Johann Weikhard, founded the princely line that still exists today.

Johann Weikhard von Auersperg was born in Seisenberg Castle in 1615. He became a personal favourite of Emperor Ferdinand III (only a few years older), and in 1640 was appointed chamberlain and tutor to the Emperor’s son, Ferdinand IV, King of the Romans (the title held by the son and assumed successor of the Holy Roman Emperor). Auersperg was then sent to Westphalia to negotiate the settlement of peace for the Thirty Years War. He was rewarded with lands and elevation to the rank of Prince of the Empire in 1653.

But in order to secure this rank, Johann Weikhard needed to acquire an ‘immediate fief’, a territory subject to no other prince than the emperor, and conveniently there was one available: Tengen (or Thengen) near the western shores of Lake Constance in southern Swabia. It was a very small lordship (about 70 m2), but, recognised by the Emperor as a ‘princely county’ in 1654, it was enough to secure the Auerspergs a seat in the Chamber of Princes in the Imperial Diet. Tengen Castle is on a rocky spur above the town, and was already a ruin—the Auerspergs weren’t planning on moving there anyway, so very far from their centre of operations—and it remains a ruin today.

But Ferdinand III also rewarded his friend with another extraordinary gift, the Duchy of Münsterberg, in 1654. Münsterberg, even more than Tengen, was a semi-sovereign duchy, one of the many that made up the Duchy of Silesia, part of the Crown of Bohemia (which was by this point also held by the Habsburg emperor). When Silesia was cut off from the Kingdom of Poland in the early fourteenth century, this was one of the many smaller duchies into which it fragmented. Its castle, known today as Ziębica in Polish, was built around this time. The duchy also included the semi-autonomous city of Frankenstein (Ząbkowice). When the last of the original Polish (Piast) royal dukes died out in 1428, the duchy passed through various hands until it was held by the Czech Poděbrady family, 1456-1569. It then was ruled directly by the Habsburgs until it was given to Auersperg. The town of Münsterberg was prosperous and generated healthy revenues for its new dukes, but the ducal seat was at Frankenstein, where the old medieval castle had been given a Renaissance makeover in the 1520s. It was abandoned as a residence in the 1720s, and has been a ruin ever since.

For a princely residence in Austria itself, the 1st Prince of Auersperg was given the Castle of Wels, in Upper Austria. The castle or burg of the town of Wels, on the river Traun, a tributary of the Danube, was built by the Babenbergs, the first dukes in this region, in the 1220s, then passed with their possessions to the Habsburgs later in that century. Emperor Maximilian I rebuilt it in Gothic style and died here a few years later in 1519. The Auerspergs would hold the castle and lands as a county (referred to as ‘princely county of Wels’ though I’m unsure why since there’s no sovereignty attached to it) until 1865 when they sold it to another family. Since 1937 it has belonged to the city itself and today houses the Wels City Museum.

Back home in Ljubljana, to celebrate his dramatic rise to the top of the aristocracy, Prince Johann Weikhard built a huge city palace, next door to one already recently built by his older brother Count Wolfgang Engelbert, in what is now the university district of the old town. The Prince’s Palace (Knežji Dvorec) was badly damaged by an earthquake in 1895 and torn down—in the 1930s, the National Library was built in its place. The Auersperg Palace (aka the Turjaška Palača) still exists, but was sold to the city in 1937 and today houses the City Museum.

The 1st Prince of Auersperg continued his rise, and from 1665 to 1669 was the head of the Aulic Council for Emperor Leopold I, essentially ‘prime minister’ of Austria. Once again acting as an international diplomat, he concluded a secret treaty with Louis XIV by which France and Austria would agree to split the Spanish succession once King Carlos II of Spain would die (which was expected to be soon). But enemies back in Vienna accused the Prince of getting too cozy with the Sun King and making secret deals that would benefit himself and his family, so Emperor Leopold sacked him in 1669 and sent him home to his estates in Carniola, where he died nearly a decade later. His older brother died unmarried, so the Prince added the county of Gottschee to his already very large domains in the region.

The descendants of the middle brother, Herward, remained local and retained the hereditary offices of chamberlain and marshal of Carniola. One of these, Count Anton Alexander, became a leader of the liberal nationalist movement of young Austrians in the 1830s-40s, and a supporter of the revival of Slovene identity and folklore. He wrote poetry (in German) of a political and nationalist nature under the pseudonym ‘Anastasius Grün’.

The 2nd Prince of Auersperg, Johann Ferdinand, succeeded his father in 1677 and died in 1705, leaving behind only a daughter, so the patrimony passed to his brother, Franz Karl, 3rd Prince, who died less than a decade later. The latter had made more of an impact as a soldier in the last two decades of the seventeenth century, rising to the rank of Artillery General and Governor of Karlstadt (Karlovac) in Croatia. His son, Heinrich Joseph, 4th Prince, returned the family to its favoured position at the Habsburg court that had been lost by his grandfather. He rose to the position of Grand Master of the Court under Emperor Charles VI in the 1730s, then served as Grand Equerry then Grand Chamberlain under Empress Maria Theresa in the 1760s-70s, also acting as governor to the young heir, Archduke Joseph (who became Emperor Joseph II). There were setbacks too: in 1742, Austria lost the province of Silesia to Prussia in the War of Austrian Succession—this meant that the Duchy of Münsterberg was converted from a semi-independent principality into a fief of the Hohenzollerns in Berlin. Eventually, the family sold Münsterberg to the King of Prussia, in 1791, and were compensated by the elevation of the County of Gottschee into a duchy by Emperor Leopold II. This is quite extraordinary—there are no other duchies within the territories of the Austrian Habsburgs (they alone were dukes of Carinthia, Styria, etc), with the exception of those in Silesia, like Münsterberg.

Then there were potential gains acquired through matrimony: through his first marriage, in 1719, to a Princess von und zu Liechtenstein, the 4th Prince acquired several properties in Bohemia and Moravia. None of these became central Auersperg residences, and were sold within the next two generations. By his second marriage in 1726, to a Princess von Trautson, he gained a potential great succession in the Tirol, as well as the county of Falkenstein closer to Vienna in Lower Austria. This succession was secured by his son’s marriage to his step-mother’s niece in 1744—resulting in the creation of a junior line, Auersperg-Trautson, to which we’ll return.

The 4th Prince of Auersperg died at the grand old age of 85 in 1783. He left many many children who married into the Austrian and Czech high nobility. Karl Joseph, the 5th Prince, reigned as head of the house until 1800. His younger brother Johann Adam had been raised to the rank of prince on his wedding in 1746 (before this point, only the head of the family was a prince), and acquired a grand palace in Vienna that became the family’s chief residence in the imperial capital. The ‘Rosenkavalier Palace’ or Palais Rofrano had been built in the first decade of the eighteenth century on the western edge of the old city, in a newly developing suburb, Josefstadt (behind what is now the Austrian Parliament building). Johann Adam acquired it in 1777 and it was renamed the Palais Auersperg. Inside, it had a well-known grand hall in which concerts were regularly held: Gluck in the 1760s, and now Mozart and Haydn in the 1770s-80s. The Palace housed the exiled Swedish royal family, 1827-37. During World War II, it was used to hide resistance fighters and today is commemorated as the place where a provisional government committee met to plan the rebirth of postwar Austria. During the war, the Palace had passed to a sister of the Auersperg prince and it is now privately owned, though still used for grand events like balls and concerts.

One of the youngest brothers of the 5th Prince, Joseph Franz, entered the church and rose through the ranks to become bishop of Lavant then Gurk (in southern Austria), then Prince-Bishop of Passau in 1783, and finally cardinal, 1789. He was a builder, re-fashioning episcopal residences in all his dioceses, notably the Passau summer residence, Schloss Freudenhain. He was also a passionate follower of Enlightenment reform, and was closely aligned to the movement led by Emperor Joseph II: he supported toleration for Jews, religious reforms against superstition in his diocese, and constructed schools, hospitals and theatres, believing the latter to be morally edifying for his flock.

The two eldest sons of the 5th Prince of Auersperg divided the succession, with the elder brother, Karl, receiving the princely title and the dukedom of Gottschee, and the younger, Karl, taking on the succession of their mother and step-grandmother and adding their name to his own: Auersperg-Trautson. The Trautson family were an old Austrian noble house who were raised to the rank of Imperial princes in 1711—but there were only two holders of this title and the line became extinct in 1775. Trautson history reaches back to the early Middle Ages when they took possession of important castles that guarded either side of the Brenner Pass, once the dividing point between northern and southern Tirol, but now the frontier between Austria and Italy. For several generations they were hereditary Landmarshalls of the County of Tirol (the presiding officer over the local assembly). Castle Trautson, high above the river Sill, dates back to the 1220s, and was largely destroyed by an air raid in World War II by bombers aiming for the Brenner railway bridge and tunnel that passes directly beneath the castle—but an elegant chapel from the 1680s survived. The ruined castle is still owned by the Auersperg-Trautsons, as is Castle Sprechenstein, on the other side of the pass, now in Italy. It is still private and not open to visitors.

In addition to these Tirolean castles, solitary stone fortresses on rocky outcroppings deep in the Alps, the Trautson inheritance also included a more stylish country house, Schloss Goldegg, west of Vienna in Lower Austria (not far from the famous Melk Monastery). A medieval castle here had been rebuilt and enlarged in the early seventeenth century, then purchased by the Trautsons in 1669, and now passed to the Auerspergs. The senior line of princes retained it as their main country seat in Austria until it was inherited by a daughter in 2015 and passed out of the family.

Meanwhile, another house, not far away, has been the seat of the cadet branch of Auersperg-Trautson since they purchased it in 1930: Schloss Wald. It was similarly an old castle expanded in the early modern period, and is still held by the family today. The current head of this branch is Prince Franz Josef (b. 1954) who married Archduchess Maria Constanza in 1994, a granddaughter of Austria’s last emperor.

The other main Trautson estate in Lower Austria was the county of Falkenstein and its ruined castle, which was not retained by the Auersperg family since the inheritance was contested by another princely family, the Lambergs (who happened also to be an old Carniola family), so it was sold in 1799. Across the border in Bohemia, the Trautson succession included several properties that were divided between the senior and junior lines. The most esteemed of these, Vlašim (Wlaschim in German), had been favoured by the first Auersperg to acquire it, the 5th Prince, Karl Joseph, and his wife, the heiress Maria Josepha von Trautson. Located in the hills southeast of Prague, the castle dates back to about 1300, but had also been remodelled in about 1600. The Prince and Princess developed its gardens in the style of the fashionable English Garden in the 1770s, and included numerous outbuildings for visitors and guests to enjoy, from stone grottoes and Roman temples to a Chinese pavilion. The castle and its gardens were confiscated by the Czechoslovak state in 1945, and today the buildings house a regional museum, happily preserving many of the gardens’ finest features.

The 6th Prince of Auersperg, Wilhelm I, presided over the family between 1800 and 1822. During this time, the Holy Roman Empire came to an end (1806), and tiny principalities like Tengen were absorbed by their larger neighbours, in this case the Grand Duchy of Baden. The Auerspergs retained the property, but the Prince decided to sell it to the Grand Duke outright in 1811. Meanwhile, the duchy of Gottschee and other castles and estates in Carniola were annexed by the Empire of the French in 1809 as part of its new ‘Illyrian Provinces’. After this territory was regained by the Austrian Empire in 1814 it was renamed the ‘Kingdom of Illyria’, before finally returning to its previous status in 1849 as the Crown Land of Carniola within the Austrian half of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy.

The 7th Prince, Wilhelm II, was only head of the family for five years, dying relatively young in 1827. His uncle Karl von Auersperg-Trautson had no sons, so this inheritance was transferred to the Prince’s nephew, Vincenz Carl, who assumed the title Prince of Auersperg-Trautson. He became Grand Chamberlain of the Austrian court in 1863. It is his descendants who hold the Trautson lands today.

The new head of the family overall, Karl Wilhelm, 8th Prince, was only 13, but eventually he grew and by the 1840s emerged as a youthful leader of the liberal or constitutional party, opponents of the arch-conservative Prince Metternich (as we’ve seen with his soon-to-be kinsman, Count von Breuner, above). When a constitution was finally granted in 1861, Emperor Franz Josef thus turned to Prince von Auersperg to serve as the first President of the new Austrian House of Lords. He also served as a member of the Bohemian Landtag and at times as that body’s president. After the Compromise of 1867 (creating an entirely separate Kingdom of Hungary), the Emperor asked Auersperg to form a liberal government for the Austrian half (‘Cisleithania’) of the Dual Monarchy. But he resigned after only a year as Minister-President due to conflicts with concessions being demanded by ethnic minorities, notably the Czechs—for although he considered himself a liberal, like most of his landowning magnate class, he favoured centralisation and a blending of cultures, not the separatism being demanded by nationalist movements. From 1868 to 1879, he resumed his position as President of the Austrian House of Lords. He had no children and died in 1890.

Meanwhile, the Prince’s brother Adolf, was also a political force in Vienna. Born at Vašim, he also served a term as president of the Landtag of Bohemia, 1867-70, then a similar role in the province of Salzburg, 1870. From 1871 to 79, he took on his older brother’s role as Minister-President of Austria, but he too resigned over a question about Slavs, this time in Bosnia (newly occupied in 1878). His resignation effectively marked the end of liberalism as a leading party in Austria.

Adolf’s son Karl took over as 9th Prince of Auersperg in 1890. He was quite close to Emperor’s son Crown Prince Rudolf (born just a year apart), and was shattered by his friend’s suicide in 1889. He took up his seat in the Austrian House of Lords and rose to be its vice-president from 1897 to 1907. He still sat as a member of the liberal-constitutional party, but never rose to greater prominence in the Imperial government. He turned much of his attentions instead to his estates back in Carniola and his role as president of the diet there, and in 1907 was elected to represent Gottschee in the lower house of the Austrian Parliament. In 1885, he married Countess Eleonore von Breuner, which brings us back to the start of this story and into the orbit of the Von Trapp family.

After 1918, princely and ducal titles were abolished in Austria, and Carniola became Slovenia, one of the component parts of the new Kingdom of Yugoslavia. The 9th Prince died in 1927, leaving the now empty titles to his grandson, Karl Adolf—his elder son Adolf had died in 1923, while his younger son Karl assumed the name Auersperg-Breunner, and founded a new branch with the Breunner family properties, many which were surely well known to the Von Trapp cousins—when visiting Vienna for example. The heads of both branches moved to South America after the Second World War, the senior line to Uruguay and the junior to Argentina. Some remain in South America today while others have returned to Europe. The head of the junior branch, Prince Franz-Josef of Auersperg-Breuner (b. 1956), has a son and heir, Camilo, born in Buenos Aires, while the head of the senior branch, Adolf Karl, 11th Prince von Auersperg (b. 1937), has a son and heir, Carl Adolf, born in Montevideo.

Many Austrian nobles emigrated to the Americas, like the Von Trapps, in the 1940s either for an innocent fresh start after the horrors of the Nazi era in their country or in many cases to escape their darker histories. One of the Auersperg-Trautsons was Alfred, a leading university psychologist in Vienna in the 1930s who became a Nazi Party member and part of the SS, and led some of the more questionable advances in neuroscience in the early 1940s. Fired from his job in 1945, he left for Brazil, then was invited to Chile to set up a psychology clinic in 1949, at a time when Chile’s government was shifting to the right. Another younger son from the Trautson branch rose to prominence, but this time—again making a connection with the Von Trapps—in music: Johannes Auersperg was a double bass player and teacher in Austria in the 1960s-70s. An early supporter of the baroque music revival of that era, he formed the Austrian Barocktrio and later led the Austrian Youth Orchestra and taught at the University of Graz.

Let the sound of music play on!

(images Wikimedia Commons)

2 thoughts on “The Hills are Alive! Auersperg princes: Lords of Slovenia and Relatives of the Von Trapp Singers”