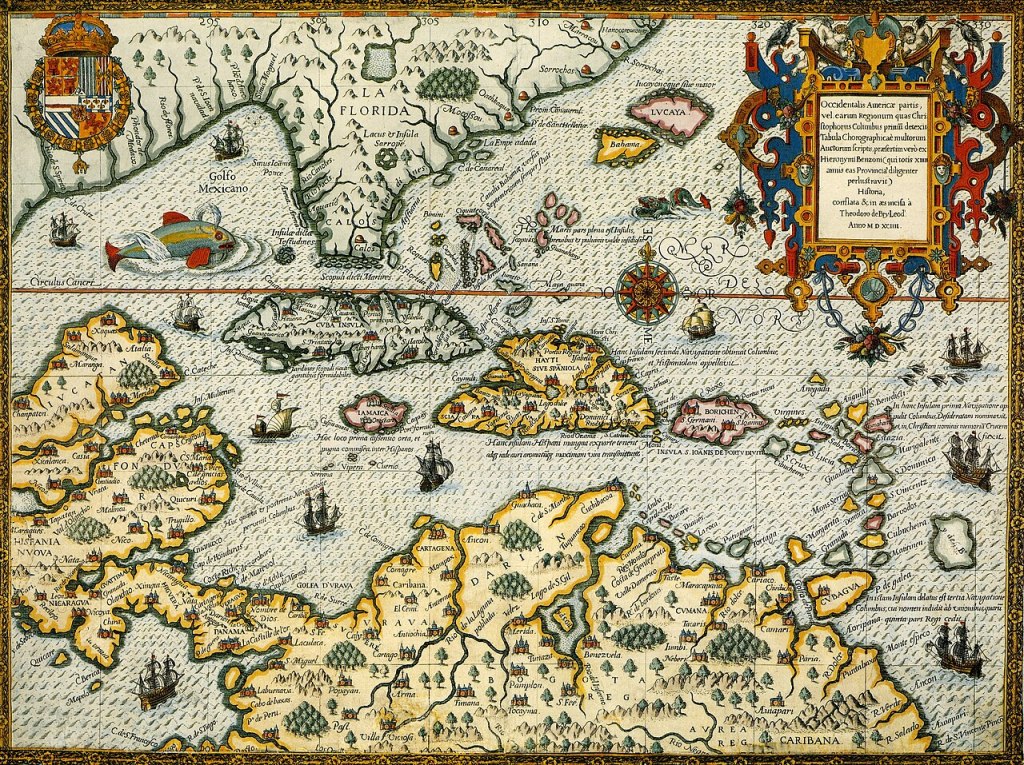

Most American schoolchildren have heard of Ponce de Leon, when learning about the early Spanish explorers of the New World—after Cortes and Pizarro heading to Mexico and Peru, most can recall that Ponce de Leon went north in 1513 and discovered a new land he named La Florida, ‘the land of flowers’. I admit, I thought for a long time that his first name was Ponce (perhaps like Ponch, from CHiPs?); it is in fact Juan, though the name Ponce was indeed once a first name borne by an ancestor from the late twelfth century. More intriguingly, the ‘de León’ part comes from that first Ponce’s son’s excellent marriage to an illegitimate daughter of the king of León, Alfonso IX. But though the Spanish explorer Juan Ponce de León is certainly reckoned to be part of this extensive family, it is curious that scholars are unsure of exactly where he fits in its dynastic history.

The rest of the family history is well known and forms a key part of the history of the Spanish monarchy in the extension of royal power into the southern parts of the Iberian peninsula. By the early fifteenth century they were major landowners in Andalusia, with two key fortresses near the ancient city of Cadiz: Arcos and Zahara. The senior branch was even named Duke of Cadiz in 1484, but in the absence of direct male heirs, this title reverted to the Crown less than ten years later. The Duke’s wealth and subsidiary titles, however, passed to a junior branch, who were shortly after created Duke of Arcos. Their descendants were prominent grandees in the seventeenth century, with two brothers in particular, Rodrigo and Luis, serving the Habsburgs as viceroy and governor in Naples and Milan; while their sister, Elvira, was head of the household of Queen Mariana of Austria, regent for her young son Carlos II. Like many of the ducal families of Spain in this century, the dukes of Arcos swept up heiresses of other ducal families, such that by the 1720s the 7th Duke of Arcos was also Duke of Ciudad Real, Duke of Maqueda and Duke of Nájera, while his brother the 1st Duke of Baños also became 7th Duke of Aveiro. Although there were four healthy sons in the next generation, none of them produced any children, so this massive windfall—the collected inheritances of the houses of Ponce de León, Cárdenas, Manrique de Lara and Lencastre—all passed in 1780 into the house of Pimentel-Benavente, and on to one of the grandest of all Spanish aristocratic families, the Téllez-Girón dukes of Osuna—but their story will be told elsewhere.

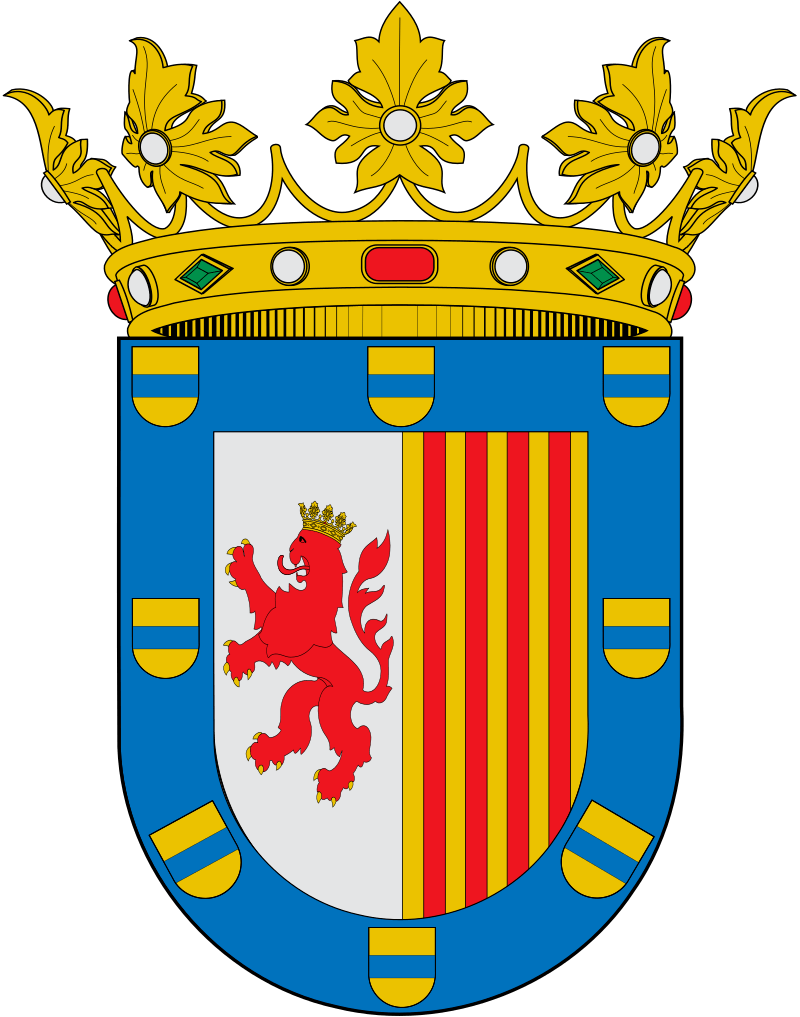

The coat of arms of the family also point to their semi-royal origins: with the red lion of León on one side, and the red and gold stripes of Catalonia on the other—all framed by eight small shields of blue and gold representing an old family from Navarre. This reference to Catalonia recalls the ancient surname of the family, Cabrera, so we can start there.

Cabrera was once an independent viscounty in the eastern foothills of the Pyrenees, founded in the early eleventh century and eventually absorbed into the County of Barcelona, aka the Principality of Catalonia. The name Ponce comes from here too: as the Spanish version of the Catalan name Ponç (itself a variant of the then common French name Pons, which is related to the Roman name Pontius). Ponç de Cabrera came to the court of Alfonso VII, King of Castile and León, in about 1130, in the entourage of his new wife, Berenguela, daughter of the Count of Barcelona. After service in wars in Castile, Ponce was created a count in 1143 and became the King’s Mayordomo in 1145. He married his daughter Sancha to the Mayordomo of Alfonso VII’s younger son, King Fernando II, Count Vela Gutierrez, who adopted the Cabrera name and arms. Vela Gutierrez was the son of Count Gutierro Vermudez (Spain’s nobility was using patronymics still at this stage) who is thought to be descended from the Vermudez (or Bermudez) clan of Asturias—Bermudo Nuñez is said to be a grandson of King Ordoño I of Asturias (died 866). So, ancient stock indeed.

Sancha and Vela had several sons, who took the surname Vela or Velaz de Cabrera. The youngest, Abbot Pedro, was Mayordomo and Chancellor of King Fernando II of León, while his older brother, Ponce, became alférez, or master of arms, of his son Alfonso IX in 1188. Ponce’s son Pedro Ponce de Cabrera took over his father’s role as head of the military household, and continued it into the reign of Fernando III. Fernando reunited both Castile and León from 1230 and launched a massive crusade to reconquer the south of the Iberian peninsula from its Muslim lords. Cabrera assisted in the conquest of the Umayyad capital city of Córdoba in 1236, and was given lands in that area in reward. He had already been rewarded a few years earlier with the hand of the King’s illegitimate sister (the daughter of Alfonso IX), Aldonza de León, and their son, Fernan Perez (using the patronymic for Pedro) began to add the surname Ponce de León. This generation continued to wield extensive power: Fernan was Mayordomo for Alfonso X, Ayo (governor) of Fernando IV, and Adelantado (king’s representative or senior magistrate) of La Frontera, aka Andalusia, from 1290; his brothers Ruy and Pedro became heads of orders of knighthood, the elder as Grand Master of the Order of Calatrava, and the younger as Comendador mayor of the Order of Santiago.

In the next generation, Pedro Ponce de León continued service in the same vein, as both Mayordomo mayor of King Fernando IV and Adelantado of Asturias, and maintaining the family landholdings in the north; his brother Fernando, Master of the Order of Alcántara, acquired a new lordship for the family in the south in 1309: Marchena in the plains east of Seville. This was an area rich with olive plantations—the name of the town even comes from marshenah, ‘olive trees’ in Arabic. It had initially been taken from the Moors in 1247. Much later, in the 1880s, Marchena was given again as a title, now a dukedom, for junior members of the royal house of Spain (and it still exists today). An early Moorish fortress was converted into a palace, later known as a the Ducal Palace of Marchena; a ruin by the nineteenth century, King Alfonso XIII had its main gateway transferred to the Royal Alcázar of Seville.

Fernando Ponce de León had acquired Marchena through marriage to a daughter of Guzmán el Bueno, one of the chief warlords in Andalusia (I’ve written about his family here). She was also heiress of the town of Rota, an ancient city founded by Phoenicians on the Bay of Cadiz, with a large Castillo de la Luna from the 1290s overlooking chief shipping lanes coming into the Mediterranean. This area around Cadiz would become a chief centre of operations for the Ponce de León dynasty for centuries to come.

The lords of Marchena were less prominent at court than their ancestors, but continued to add to their landed wealth in the south (they became known as ‘rico hombres’ of Castile). Pedro, 2nd Lord of Marchena, fought alongside Alfonso XI in the 1330s-40s, and was rewarded with more lands in Andalusia. He was buried in the Monastery of San Augustin in Seville, which was for many years the family sepulchre (but was moved in the nineteenth century to the Church of the Annunciation). Juan, 3rd Lord of Marchena, was involved in one of the many revolts against Pedro I (‘the Cruel’) and was executed in Seville in 1367; soon after, his sister Beatriz’s lover Enrique of Trastámara overthrew his brother Pedro to become King Enrique II of Castile—it is an interesting aside to note that Beatriz’s son by Enrique became the first duke of Benavente, and the heirs to that dukedom would ultimately also inherit the dukedom of the Ponce de León family. Her brother Pedro became 4th Señor of Marchena and married the heiress of another lordship, Bailén, in the former kingdom of Jaén. This old city was located in the agricultural interior of Andalusia, close to the site of one of the grandest battles of the Reconquista, Las Navas de Tolosa (1212).

Their son Pedro became 1st Count of Medellín, in Badajoz (western Castile), in 1429, which he soon exchanged for the town of Arcos de la Frontera, much closer to his power base near Cadiz. Arcos had been the seat of an independent Moorish taifa (or minor kingdom) in the eleventh and twelfth centuries, and sat high on top of a cliff with the river Guadalete winding around it on three sides. The castle, from the eleventh century, was rebuilt in the fifteenth and is still linked to some ruins of Arab and even Roman city walls. The Guadalete river emerges from the Sierra Nevada mountains and flows north for a distance before turning south and west and flowing to the sea in the Bay of Cadiz. Somewhere along these banks is the site of the Battle of Guadalete, 711, which marked the end of the dominance of the Visigoths in Iberia and the rise of the Umayyad Caliphate.

Juan Ponce de León, 2nd Count of Arcos, was a supporter of King Enrique IV against noble rebels, and captured the city of Cadiz in 1466 from supporters of the King’s half-brother Infante Alfonso. In thanks, the King created him Marques of Cadiz, 1471. Juan married another Guzmán, the most powerful family in the region, as did three of his daughters, and indeed did his brother Luis: Teresa de Guzmán, Señora of Villagarcía, who founded a junior branch, to which we will return below.

But the 1st Marques’s marriage was not fruitful, so he married his concubine and legitimised his sons. The first died before his father, so the second, Rodrigo, became 2nd Marques of Cadiz and 3rd Count of Arcos. The third, Manuel, was given Bailén and eventually made a count (1522)—his descendants held the county of Bailén until 1618, when their lands were re-integrated into the main line of the House of Arcos.

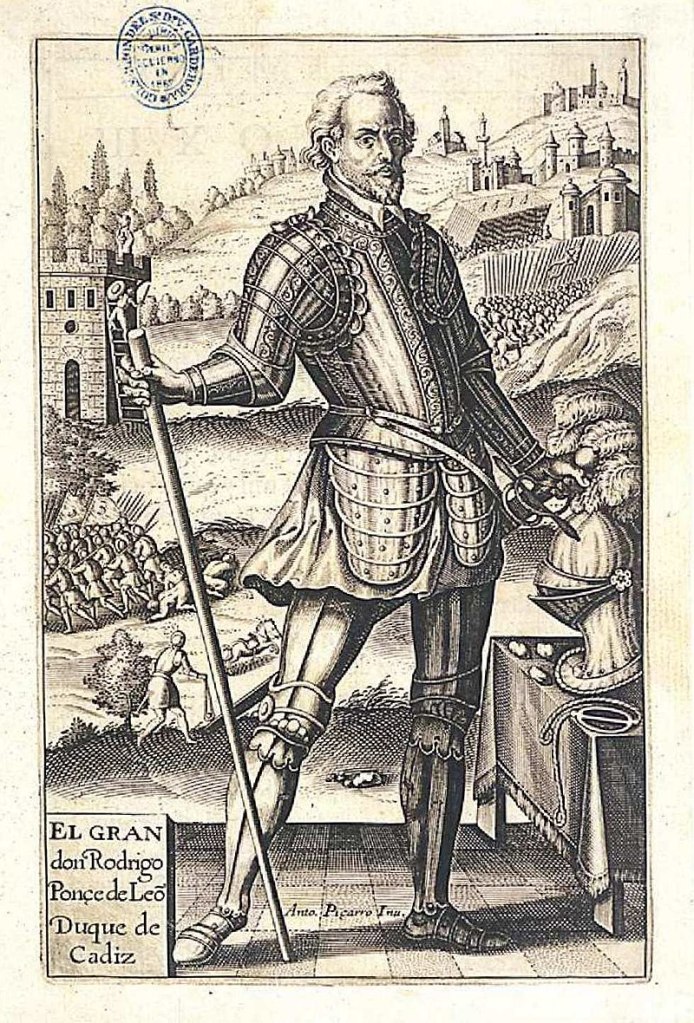

The House of Arcos was propelled into premier rank by Rodrigo, 2nd Marques of Cadiz, who had fought with his father in service of Enrique IV, and for Enrique’s daughter Juana against her cousin, Isabel. But when Isabel emerged triumphant as Queen of Castile in 1476, Cadiz swore loyalty to her and was forgiven, his titles confirmed (despite having married the daughter of the opposition leader, Juan Pacheco). Rodrigo proved his loyalty soon enough by leading Isabel’s armies in the conquest of the Kingdom of Granada. In 1483, he re-took the city of Zahara, in the Sierra de Cadiz—whose capture by the Moors in 1481 had been the pretence to launch this war. Earlier that year, he had captured King Muhammad XII, better known as Boabdil, but convinced the Catholic Kings to release him so as to foment civil war in Granada. He was created Duke of Cadiz in 1484. The Duke then went on to take the fortress of Casares on the western edge of the Sierra Nevada (1485); the city of Málaga (1487); then took part in the final capture of the city of Granada itself in January 1492. His titles expanded further: Marques of Zahara and Count of Casares, with an aim of transmitting the first of these to his daughter and the second to his grandson.

The Duke of Cadiz died in August 1492 in Seville. Queen Isabel decreed that the ducal title could not be transmitted to his daughter Francisca, born of a concubine, but she could be Marquesa of Zahara. The dukedom of Cádiz returned to the Crown; it would eventually be re-erected as a dukedom in the nineteenth century for the nephew of King Ferdinand VII and husband of Queen Isabel II, Infante Francisco de Asis. In 1972 it was revived again by General Franco for Don Alfonso de Borbón, one of the claimants to the Spanish throne, and after 1975 chief Legitimist claimant to the throne of France. Since 1989, the title Duque de Cádiz has been held (by tradition, not by law) by his son, Luis Antonio, who also goes by the title Duc d’Anjou (aka King Louis XX to French Legitimists).

Francisca Ponce de León was 2nd Marquesa de Zahara. This ancient Moorish fortress was also on the river Guadalete (before its flows past Arcos) and probably takes its name from the Arabic sahra (sterile, dry, rocky). It had been captured by Christian armies in 1407, and now returned to Castilian hands to become a central part of the Ponce de León patrimony. Casares, which passed to her son, Rodrigo, was located further east in the province of Málaga. Francisca was also 4th Countess of Arcos and 8th Lady of Marchena. Her husband was Luis Ponce de León, a cousin and head of the junior branch of the family, the lords of Villagarcía. This lordship, Villagarcía de la Torre, was near Badajoz and the frontier with Portugal. Its castle was built in the fifteenth century on top of a much older fortress. It survived for many centuries, but was mostly destroyed in the Carlist wars of the nineteenth century.

The Ponce de León family also acquired about this time a grand house in the city of Jerez, which was branded the Palacio de los Ponce de León and remained their primary seat for the next two centuries. In the late eighteenth century it passed to the Ysasi family, who later donated it to the city of Jerez. Today it houses a convent school.

Luis and Francisca were married in 1487 and were permitted to retain most of the late Duke’s properties, but not the ducal title—as a special concession, however, their son Rodrigo, born in 1488, was named 1st Duke of Arcos in 1493. The line thus continued through him.

Before proceeding to the dukes of Arcos, however, this is where scholars think to insert the explorer Juan Ponce de León. He may have been the younger brother of Luis, Lord of Villagarcía, and probably served with his cousin the Duke of Cadiz in the conquest of Granada in 1492. For such a prominent historical figure, it is strange that his exact parentage is not known, or even his birthdate (1460? 1474?). To me this sounds like something fishy is going on… so perhaps he was an adopted son, or product of adultery (though in that time illegitimate children were rarely hidden amongst the Spanish aristocracy). Speculating wildly, maybe he was a secret child of one of the last kings of Granada, captured and raised as a Christian by the Duke of Cadiz? Such things have been known to happen. Anyway, what is known is that he sailed on the second expedition led by Christopher Columbus to the Indies in 1493, and stayed in the region (with some trips back to Spain) for the rest of his life. The governor of Hispaniola charged him with putting down a rebellion of native Tainos in 1504 and was given that region (the eastern end of the island) to govern, with lands and slaves for his plantations. Hearing tales of gold to be found on the neighbouring island of San Juan (today called Puerto Rico), he was charged with a formal expedition in 1508. Gold was indeed found, and a new settlement started, Caparra. Here he settled with his family as governor of the island from 1509. The capital was later moved a bit to the east, closer to the port, and renamed San Juan.

Ponce de León was a brutal governor, forcing the natives into slavery and fighting with Diego Colón (Columbus’s son) who claimed the right to rule over him from Hispaniola. King Ferdinand back in Spain seemed to want to support Ponce de León in the face of Colón’s better legal claims, so encouraged the former to travel north to explore other islands, with a very generous contract that would allow him to keep much of the spoils. The contract mentions gold and slaves, but nothing about a ‘fountain of youth’, so that story was invented later—first appearing in biographies about Ponce de León long after his death. He sighted land in Easter 1513, and the name Florida may refer to the Spanish tradition of celebrating La Pascua Florida (‘flowery Easter’). That year, his crew explored the east coast, the keys, the west coast perhaps as far north as Tampa Bay, then returned to Puerto Rico. He travelled to Spain and was re-confirmed by the King as governor, and given a coat of arms (said to be a first for a conquistador, but certainly not something he would have needed if he was indeed the son of a Ponce de León lord?). In the spring of 1521, he organised a large-scale colonisation expedition to Florida, aiming for somewhere on the southwest coast—but they were chased off by natives and he was wounded in a skirmish; they retreated to Havana, Cuba, where Juan Ponce de León died later that year. He is buried in the cathedral of San Juan, Puerto Rico.

Another Ponce de León of this generation who played a—very brief—part in the governing of the new Spanish colonies was Luis, a judge in Cordoba, who was appointed by the King to travel to Mexico in 1526 as Governor of New Spain, in an effort to restore order to the government of Hernán Cortés. He arrived in July and died after only a few days—Cortés was suspected but the King was powerless to do much about it.

There are two other Juan Ponce de Leóns associated with the history of Puerto Rico. As was common, a Spanish nobleman often used his mother’s surname if she was of higher rank (which may explain the unclear links with both the governors of Puerto Rico and New Spain above), so we have the conquistador’s daughter’s son, Juan II, a coloniser of the island of Trinidad and briefly governor of Puerto Rico in the 1570s, and his son, Juan III, coloniser of the south coast of Puerto Rico for whom the island’s second city (Ponce) is named.

Still another with this surname, Pedro Ponce de León, was a cleric and an advisor to King Charles (Emperor Charles V). Like Juan II above, he was actually only a Ponce de León via his mother. He made his mark as a bishop in Spain, first in Ciudad Rodrigo then in Plasencia (1560), and amassed one of the largest private libraries of his time—now part of the royal collections in the Escorial. In 1572, he was appointed Grand Inquisitor of Spain, but died before he could take up the office.

Meanwhile, the 1st Duke of Arcos consolidated his family’s holdings in Andalusia inherited from his mother and grandfather. He married Isabel Pacheco, whose grandfather had been the same leader of the rebellion against Queen Isabel noted above. The Duke served the Crown as the alguacil mayor (or sheriff) of Seville, and died in 1530.

The 2nd and 3rd dukes did not play a major role in history: they fought in the King’s wars abroad in Flanders and at home in Iberia—against Moriscos, Portuguese, and English pirates invading their home region of Cadiz (1587). Both dukes were awarded knighthoods in the Order of the Golden Fleece like others of their class.

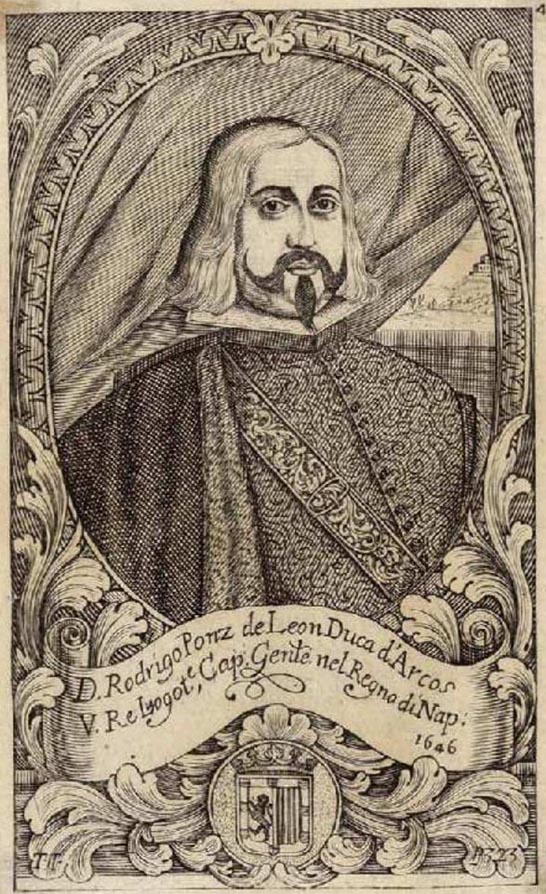

The son of the 3rd Duke, Luis, 6th Marques of Zahara (the title used for the heir), died before succeeding, so the title passed in 1630 to another Rodrigo, 4th Duke of Arcos. He is probably the most famous member of the family, as Viceroy of Naples from 1646. He successfully suppressed a popular rebellion led by the fisherman Masaniello in July 1647, only to lose control a month later when the Neapolitans proclaimed a republic. He was recalled to Spain in disgrace and replaced as viceroy, and died a decade later. Arcos became the main baddie in an opera about the Masianello revolt, La Muette de Portici (though he’s called ‘Alphonse, Comte d’Arcos’), composed by Daniel Auber, which premiered in Paris in 1828—it became famous as the opera that birthed a nation when a riot began during the second act (supposedly in the duet ‘Amour sacré de la patrie’—sacred love of the fatherland) when it was staged in Brussels in August 1830.

By the time of the 4th Duke’s death, his sister Elvira, Marquesa de Villanueva de Valdueza, was rising in prominence as Camarera mayor of Queen Mariana (from 1654). Mariana became regent of Spain for her son King Carlos II in 1665, making her chief lady one of the most powerful women in Spain. During her regency, Doña Elvira was in charge of the Queen Mother’s correspondence and arranging access to her chambers for visiting diplomats. Her brother Luis was at the time serving as Governor of Milan, which was, after Naples, the most important possession of the Spanish Crown in Italy. He died there in 1668.

Francisco, 5th Duke of Arcos, married three times, but died childless in 1673, leaving his titles and estates to his brother Manuel. The 6th Duke had already married Maria de Guadalupe de Lencastre, Duchess of Aveiro and Duchess of Maqueda, who has already been written about in context of the Portuguese dukedom of Aveiro. Part of an agreement by the King of Portugal to allow her to use the Portuguese titles in 1679 was that she had to move back to Portugal; her husband refused to grant his permission, so she legally separated from him and moved to Lisbon. It was agreed that their eldest son would be heir to the Ponce de León and other Spanish titles, while their younger son would inherit those of Portugal.

Duke Manuel died in 1693, so his son Joaquin became 7th Duke of Arcos, and also duke of Ciudad Real, Maqueda and Najera. He held the prominent positions in Spain of Adelantado mayor of Granada, Comendador mayor of Castile for the Order of Calatrava, and played an important role in the War of Spanish Succession by publicly adhering to the new Bourbon king, Philip V, bringing his huge fortune and extensive patronage networks with him. The King in return named him to his Council of State and Viceroy of Valencia, 1705-06. The Duke’s brother Gabriel took the surname ‘de Lencastre’ and waited for his share of the succession, since their mother did not die until 1715. In an effort to retain his loyalty in Spain, not Portugal, Carlos II had created the latter Duke of Baños in 1699. I haven’t been able to find out which of the many places in Spain with this name the dukedom is based on, but it may have been Baños de la Encina in Jaén, as this town was close to the Ponce de León County of Bailén. When Don Gabriel died in 1745, this dukedom was permitted to pass to his nephew Antonio by order of the Spanish king Ferdinand VI, but he was not allowed to succeed to the Portuguese titles, which went instead to cousins in the family of Mascarenhas.

The 7th Duke of Arcos had four healthy sons, but as noted above, none of them had any children. The 8th Duke (Joaquin II) was a general serving in the Spanish armies fighting in Italy in the War of Austrian Succession—he was wounded in battle near Bologna, 1743, and died shortly after. His brother, Manuel, 9th Duke, was also a general fighting in the same campaign, and died a year later, in 1744. The titles of Arcos, Maqueda and Najera passed to the next brother, Francisco, who married in 1745 in an attempt to sire an heir, but he died in 1763 without one, leaving everything to the fourth and last brother, Antonio, who as we have seen was already titled 2nd Duke of Baños. This 11th Duke of Arcos had been an aide-de-camp to the Infante Felipe back in the 1740s when that prince (the youngest son of Philip V) was fighting to gain his patrimony in Italy (the duchy of Parma), then served as a captain in the Spanish king’s Bodyguard. In 1772, now a duke four times over, he was named Captain-General, the top rank in the Spanish Army. But he died with no direct heir in 1780 and everything was up for grabs.

The ducal titles of Maqueda and Najera went in one direction, and the titles of the House of Arcos went another, to the niece of the 5th and 6th dukes, Maria Josefa Pimentel de Borja, 12th Duchess of Benavente in her own right, and Duchess of Osuna by marriage. There’s a lovely portrait of the 12th Duchess of Arcos by Goya (1785). All her titles passed to her grandson, the 11th Duke of Osuna, of the house of Téllez-Girón, in 1834.

In 1882 the 12th Duke of Osuna (and 14th Duke of Acos) died and his many many titles were fought over in the courts for a decade. In 1892, the dukedom of Arcos was awarded to a nephew, Count José Brunetti (son of a count from Pisa, Austrian ambassador to Madrid in the 1820s). The 15th Duke of Arcos—a separate title once again—was a well-travelled diplomat, with posts in South America gradually leading to stints as ambassador to the United States in 1898 (immediately following Spain’s humiliating defeat and loss of Cuba and Puerto Rico—an interesting second appearance of that island in this blog!), then in Belgium (1902), Russia (1904) and Italy (1905). While in the United States he had met and married Virginia Woodbury Lowery, granddaughter of a Secretary of the Treasury and Supreme Court Justice. Together the Duke and Duchess of Arcos became patrons of higher education (with scholarships at Harvard University) and of the arts, donating a sizeable collection of priceless paintings to the Prado after the Duke’s death in 1928. They had no children, so the title of Arcos went back to the next heir of the dukedom of Osuna, Angela Maria Téllez-Girón. The 16th Duchess of Arcos died in 2015, followed by her daughter in 2016. The title is now held by the latter’s daughter, Maria Cristina de Ulloa y Solís-Beaumont, 18th Duchess of Arcos (b. 1980).

The name Arcos is not one of the most well known amongst the dukes and princes of Spain, but the surname Ponce de León certainly made its mark in the New World!

(images Wikimedia Commons)