One of my favourite scenes in the movie Marie-Antoinette (2006) is the one in which the new Dauphine of France wakes up in the morning and is totally bewildered by the extremely complicated routine at Versailles, explained to her by the Comtesse de Noailles (whom she dubs ‘Madame Etiquette’), played by the wonderfully frosty Judy Davis. Her husband’s family had been one of the most influential at Versailles for a century, since the reign of Louis XIV—and certainly suffered for it during the French Revolution: Madame Etiquette herself was executed in June 1794. Although she was referred to in the film (and indeed at court) as a countess, she was in fact entitled to be a duchess—even twice over—of Poix in France and of Mouchy in Spain. Her husband the Duke of Mouchy was the founder of the junior line of the family, with his elder brother in the top position as 4th Duke of Noailles. The Duke of Noailles was also Duke of Ayen (the title used for his heir). So by the start of the French Revolution there were four dukedoms in one family: Noailles, Ayen, Mouchy and Poix.

Both branches of the Noailles family survived the Revolution, and continued to be prominent in France, with two particularly influential women as patrons of the avant garde art scene in the mid-20th century. I first became aware of Marie-Laure de Noailles when I was in my twenties and obsessing over the diaries of the American composer Ned Rorem. She was his patron, as she was to Poulenc, Milhaud, and many other composers and artists. She has been called the surrealists’ muse. I love the image of her, in her sixties, joining the radical movement of protesting students in Paris in 1968—driving her Rolls Royce up to the barricades in solidarity! More recently I have been reading about a distant cousin, Solange d’Ayen, who features in the new film Lee—about former model and war photographer Lee Miller, whose friends (referred to in the film only as ‘the Duke’ and ‘the Duchess’) were both prisoners of the Nazis during World War II. Both had been important patrons of the art world in Paris: Solange had been a fashion editor at Vogue in the late 1920s. She survived the prison camp; her husband did not. And in this artistic vein, there was still another woman, the Duke’s aunt, Anna de Noailles, born a Romanian princess of the house of Bibesco, who was herself an important poet and salon hostess in Paris in the first years of the twentieth century, part of the social circle of writers like Marcel Proust, and muse to numerous artists of the turn of the century.

The origins of this illustrious family, however, are far from the art scene of Paris or even the rigid etiquette of Versailles. The Château of Noailles is deep in the countryside of the Limousin province, in the basin of the river Brive (today’s Corrèze Department). This is the western edge of France’s Massif Central, a place of deep gorges, caves and grottos, an area where a number of France’s premier medieval nobility had their origins, as warriors on the frontier between the power of the King of France in Paris and the King of England in Aquitaine (as noted in a previous blog post about the Rochechouarts). The ancientness of the family, with records back to about 1220, can be detected by the simplicity of its coat-of-arms: a basic gold diagonal band on red. The castle of Noailles was built in this turbulent time in the fourteenth century, then given a Renaissance façade on its central block in the sixteenth century. Much of it burned in 1789, but was restored in the nineteenth century. Today it is private, not open to tourists.

Early members of the family got involved in the Church: Hugues de Noailles died on Crusade in 1248 at the side of King Louis IX (Saint Louis); his son and grandson were successive chaplains to the embattled pope in Rome, Boniface VIII, the last to rule there before the papacy moved to Avignon, where another Noailles served as a guard during one of the highly secretive papal conclaves. In the middle of the thirteenth century, the family married the heiress of the adjacent lordship of Noaillac (so they became lords of Noailles and Noaillac, today spelled Noailhac), and a generation later the heiress of two lordships in the Auvergne, the hilly province to the east.

The Noailles family remained a provincial family until the mid-sixteenth century when two sons (out of a total nineteen siblings!) rose to favoured positions at the Valois court. Antoine, Lord of Noailles, made his name fighting in the armies of François I against Emperor Charles V in the Piedmont in the 1540s. He was named an admiral in 1547, and later served as a diplomat in England in the 1550s, Governor of Bordeaux and Lieutenant-General of Aquitaine. His wife entered court service as lady-in-waiting to Catherine de Medici and later was dame d’honneur for Queen Elizabeth of Austria, and accompanied her back to Vienna as a widow when King Charles IX died in 1574. The Noailles women thus had a long history of running the households of French royal women, and greeting and escorting Habsburg brides long before Marie-Antoinette arrived on the scene nearly two centuries later.

Antoine’s brothers were churchmen: in 1556, François was appointed Bishop of Dax, in the far southwest of France, but was never consecrated since that city was in the hands of Protestants—he himself was suspected of adhering to the Calvinist heresy. Hoping to be promoted to the bishopric of Beauvais (but blocked by Catherine de Medici), he resigned Dax to another brother Gilles, Abbot of l’Isle, in 1562, but the latter was not consecrated either. Considered one of the most capable statesmen of his century, François was ambassador to Venice in the 1560s then to the Ottoman Sultan 1571-75, and was instrumental in building the Franco-Ottoman alliance that so destabilised Spanish power in the Mediterranean for a generation. Gilles too was a diplomat, as ambassador to England, renewing the auld alliance with Scotland in 1561, then replacing his brother in Constantinople in 1575.

In 1581, the Bishop of Dax bought the lordship of Ayen from the King of Navarre, and in 1593 this estate was erected into a county for the Noailles family. Ayen was only a short distance to the northwest from Noailles itself; being on the main north-south road between Paris and Toulouse, its strategic location meant its old medieval castle had been occupied for a long time by English troops during the Hundred Years War: stretching from Richard the Lionheart making his base here in the 1190s to a major siege by French troops in 1415, after which the castle was razed. Even without a rebuilt château, the estate at Ayen remained significant and was in fact the core of the Duchy of Noailles created by Louis XIV in 1663. It then gave its name to the separate dukedom created for the heir in 1737.

Antoine de Noailles’ son Henri, 1st Count of Ayen, was born in London while his father was posted there. He became one of the Gentlemen of the Chamber to King Henry III in 1583 and was appointed to the Council of State by Henry IV in 1597. He also served as the King’s Lieutenant-General of the Auvergne, where thirty years earlier he had relentlessly pushed out Protestants on orders of the Crown. His two sons continued this service in the region well into the seventeenth century: François, Count of Ayen, replacing his father as Lieutenant-General of Auvergne, and Charles as Bishop of Saint-Flour (in Auvergne) for nearly forty years. Ayen was also created first French governor of Roussillon, a province newly conquered from Spain in 1643, which the Noailles family would govern for several generations—until the end of the ancien regime.

In the next generation, Anne de Noailles became a protegé of Cardinal Mazarin: a field marshal in 1643 and Premier Captain of the King’s Bodyguard in 1648. In 1660, he was appointed to his father’s old post as Governor of Roussillon, with its capital in Perpignan. Three years later, Louis XIV elevated Anne to the ranks of the dukes and peers of France as 1st Duke of Noailles. He was also Marquis de Montclar in Auvergne and Marquis de Mouchy in Picardy. His wife was appointed one of the chief ladies-in-waiting of the new Spanish queen, Marie-Thérèse—as always, there was a Noailles woman in attendance on the Queen of France. The first Duchess of Noailles was Louise Boyer, heiress of the last Baron of Mouchy and brought that estate into the family, which we’ll look at more carefully below.

As ever with this family, there were several sons, many of whom rose to positions of prominence. Of the younger sons, Jacques and Jean-François made their names in the navy and the army, respectively, while Louis-Antoine and Jean-Baptiste were both senior clergymen. The latter was Bishop of Chalons, which meant he was one of the six ecclesiastical peers, but died in 1720 before he had a chance to exercise this duty at the coronation of Louis XV. Louis-Antoine held the much more important (but newer) peerage of Paris (from 1695), and as Archbishop, and then Cardinal (1699), presided over many important court ceremonies, from royal baptisms to marriages to funerals. He also had a fabulous portrait done!

But it was the eldest son who is seen as the most significant member of the family in its long history. Anne-Jules became 2nd Duke of Noailles in 1678, and succeeded his father as Captain of one of the companies of the King’s Bodyguard (Gardes du Corps). He was also Louis XIV’s aide-de-camp during the Dutch War of the 1670s, and was promoted higher and higher through the ranks, to field marshal, lieutenant general, and finally Marshal of France in 1693—he’s considered one of France’s principal generals in the Nine Years War (1688-97). He also took over his father’s post as Governor of Roussillon in 1678, then was promoted to much more prestigious (and financially lucrative) post next door as Governor of Languedoc in 1682. From here, he launched his Noailles Regiment across the Pyrenees to aid the Catalan revolt against Habsburg rule, achieving several victories, notably on the River Ter in 1694. He was appointed Viceroy of Catalonia—but becoming ill, and having annoyed the King, he handed over this post to the Duke of Vendôme and returned to court. The Marshal-Duke of Noailles returned to favour when he was honoured in 1700 with the appointment to escort the young Prince Philippe of Anjou, newly named Philip V of Spain, to the frontier. He was busy at home too fathering thirteen children survive childhood; of these, three of the daughters married well, even into the extended network of the royal family itself: Lucie-Félicité married the Marshal-Duke of Estrées, a cousin of the Duke of Vendôme, of the illegitimate branch of the House of Bourbon; Marie-Thérèse married the Duke of La Vallière, the nephew of Louis XIV’s first ‘official’ mistress; while Marie-Victoire married the Marquis de Gondrin, the grandson of Louis’ second mistress, Madame de Montespan, then later Louis XIV’s own son by Montespan, the Count of Toulouse (thus his half-uncle, which raised some eyebrows in ecclesiastical law). The last of these as Countess of Toulouse became a surrogate mother to the young orphan Louis XV and remained a strong maternal figure well into his reign.

The heir to the dukedom of Noailles, Adrien-Maurice, took over his father’s post of Captain of the King’s Guards well in advance of his father’s death in 1708, as well as the post of Governor of Roussillon—which he governed for 68 years!—and added another government, Berry, in 1698. He too rose through the ranks of the military, notably during the War of the Spanish Succession, and also became a Marshal of France. When Louis XIV died, a regency government was led by the Duke of Orléans, who appointed the 3rd Duke of Noailles as President of the Council of Finance—he was not just a figurehead, and tried actively to reform the finance system in France, now heavily burdened by the debts of Louis XIV’s many wars. He proposed a system of proportional taxes and the suppression of the dîme (the ten percent tax) collected by the Church. But as with many of the reforms of the Regency period, these were rejected by more conservative forces, and the Duke was disgraced and dismissed from the Council in 1718. He did not return to favour and to military command until the War of Polish Succession (1733-35), during which he was promoted to Marshal of France. A few years later the War of Austrian Succession broke out, and Noailles was named Commander-in-Chief of the Army of Germany—though he suffered a terrible defeat by British and Austrian forces at Dettingen in 1743. Earlier that same year, he had been appointed Minister of State by Louis XV, and in 1744 served as Minister for Foreign Affairs, but only for a few months. He resigned from his post on the King’s Council in 1756, and died a decade later, nearly 90 years old.

The 3rd Duke’s other significant contribution was territorial, in marrying—like his sisters—into the extended illegitimate side of the French royal family: Françoise-Charlotte d’Aubigné was the niece and universal heiress of Madame de Maintenon, and received from her in 1718 the Marquisate of Maintenon, about 50 km southwest of Versailles. The Château of Maintenon had been built in the thirteenth century by an eponymous family of feudal lords, transformed into a more fashionable residence by the Angennes family in the sixteenth century, then remodelled again for the secret wife of Louis XIV in the 1680s. It had three round towers and a moat connected to the nearby river Eure; its gardens were given a royal makeover by the King’s gardener, Le Nôtre. Since 1983 it has been gifted to a foundation that looks after French patrimony (Fondation Mansart) and is managed for visitors by the local council.

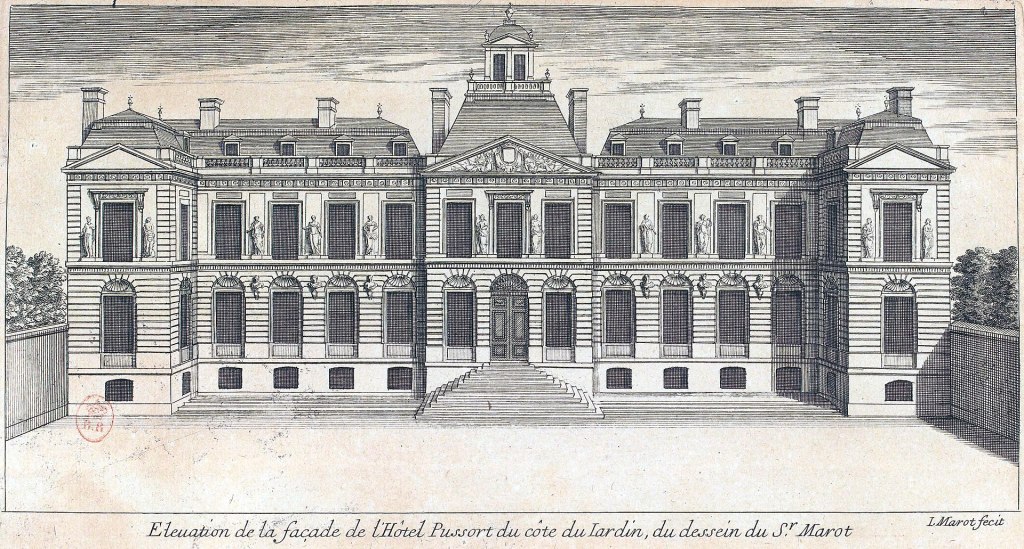

In Paris itself, the 3rd Duke acquired a grand residence on rue Saint-Honoré with gardens that backed onto the gardens of the Tuileries Palace in 1711, built in the 1670s and now renamed the Hôtel de Noailles. Confiscated during the Revolution, it was restored to the family in 1815, but soon sold and demolished to make way for the development of the rue de Rivoli.

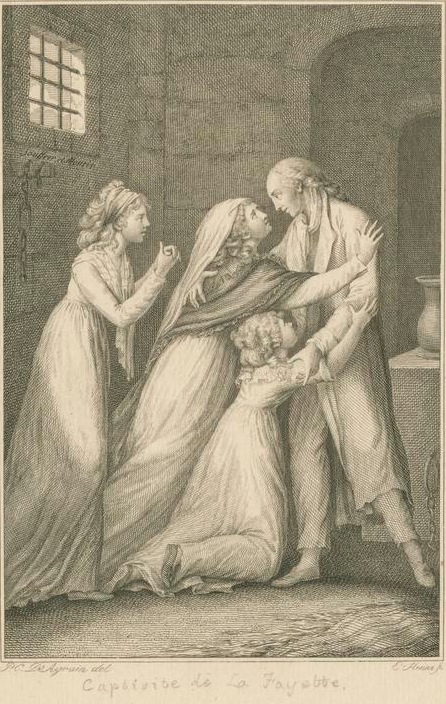

As with previous generations, more than one son of the Marshal-Duke of Noailles made his name at court and in the military. Both Louis and Philippe were promoted to the rank of Marshal of France—on the same day in 1775—and both ranked at court as dukes: Noailles and Poix. Louis, 4th Duke of Noailles, was initially known as the Count of Ayen as heir to his father—but as the latter lived so long and showed no signs of declining, the King created a new duchy of Ayen for Louis in 1737. After his father’s death in 1766, he assumed the senior ducal title of Noailles and passed the junior title of Ayen to his own eldest son. He also succeeded his father as Governor of Roussillon and Captain of the King’s Guard. He was close to Louis XV and served as his aide-de-camp when the King went to war personally in the 1740s; later that decade he joined the small social circle of the King’s new mistress, Madame de Pompadour. In contrast, his sister the Duchess of Villars was part of the Queen’s inner circle, in service as a lady-in-waiting for nearly forty years—she too was there to receive and educate the young Marie-Antoinette when she arrived from Vienna in 1770. In 1789, the 4th Duke of Noailles was named governor of the Château of Saint-Germain-en-Laye, mirroring his brother’s position as governor of the Château of Versailles. He died of old age just before the Terror in August 1793; but his wife, daughter-in-law and granddaughter were all executed in July 1794. Another granddaughter, Adrienne, wife of the famous Marquis de La Fayette, was also imprisoned at this time and narrowly missed the guillotine only to find herself living in prison again by the end of the year, this time in Austria.

Her father, Jean-Louis, 5th Duke of Noailles, also survived the Revolution, having emigrated when things heated up for the nobility in 1792. He had been a lieutenant-general in the army and a member of the Academy of Sciences in the 1770s-80s, and in general had been known for his progressive views, as was his brother, Emmanuel-Marie, Marquis de Noailles (also known as the Marquis de Maintenon), who had had a long diplomatic career in the Old Regime, as ambassador to the Dutch Republic, to Great Britain and then to Austria for nearly a decade—including the early years of the Revolution, a critical period in Franco-Austrian relations. Just as his brother was leaving France, the Marquis was recalled from Vienna and imprisoned during the Terror but was not executed. He later became a supporter of Napoleon’s Empire of the French and was created a Count of the Empire in 1813. Both brothers lived well into the Restoration period, and the 5th Duke was succeeded in 1824 by his great-nephew, Paul.

Paul, 6th Duke of Noailles, was head of the family for fifty years. He was a historian, writing a history of his ancestor, Madame de Maintenon, in four volumes (amongst other works), and weas elected to the French Academy in 1849. He also cultivated progressive business interests and was president of two railroad companies. He left two sons: the elder, Jules-Charles, became 7th Duke of Noailles, while the younger, Emmanuel-Henri, continued the family’s diplomatic tradition, and served as ambassador to the United States, to Italy, to the Ottoman Empire and to Germany from 1896 to 1902. He was also a historian and wrote a large history of Poland.

The 7th Duke of Noailles spent most of his life as Duke of Ayen (as heir), then was head of the family for only ten years, 1885 to 1895. He had acquired by marriage in 1851 a new country residence for the family, the gorgeous eighteenth-century Château de Champlâtreux in the Val-d’Oise, northwest of Paris. Initially constructed by the Molé family of Paris parlementaires (and financed by money from the immense succession of the famous banker Samuel Bernard), it has remained the main Noailles residence ever since, and is visitable in the summers.

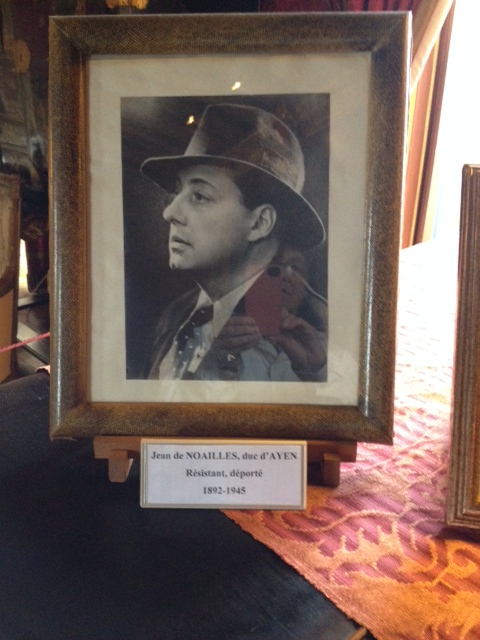

His son, Adrien, was 8th Duke until 1953, residing at the Château de Maintenon and participating in early Olympic Games, as an equestrian, as did one of his daughters, in tennis. His son and heir, Jean, Duke of Ayen, was also a sportsman, competing in shooting, then made his name as a leader of the Paris Resistance and died in the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp in April 1945, just days before the end of the war. It was his wife, Solange d’Ayen, that is mentioned at the start of this post. Their son Adrien-Maurice also died during the war, fighting in the Maquis in October 1944.

The title thus passed to the 8th Duke’s nephew, François, who died in 2009—at age 103!—and was succeeded by his son Hélie, the 10th and current Duke of Noailles (b. 1943). He had a career in the 1970s-80s in government and in diplomacy—notably with a stint in the embassy in Washington DC, 1982-86. Further American ties were made when, as a distant link by marriage to the Marquis de La Fayette, he was chosen to be President of the French Sons of the American Revolution. His heir is Emmanuel, Duke of Ayen, born in Washington DC in 1983.

We must scoot back to the eighteenth century and to the creation of the second major branch of the House of Noailles. The younger brother of the 4th Duke of Noailles, Philippe, was at first called ‘Comte de Noailles’, but in 1729 he inherited a property from his aunt by marriage that had a curious rank (by French standards) the ‘principality’ of Poix. That same year, though still a minor, he was appointed to the very prestigious post of Governor of the Château of Versailles, with responsibilities ranging from security to staffing to building works. The Prince of Poix took over this role fully as an adult from 1740; then in 1746 accompanied his father on an embassy to Spain and was honoured with the rank of Grandee of Spain and the title ‘Duque de Mouchy’ in 1747. This was certainly a nod from the Spanish king for all the work done by the Noailles family in Franco-Spanish relations in the past century, and now in helping to secure the Bourbon dynasty on its still relatively new throne in Madrid. But this ducal title did not give Philippe de Noailles a peerage, with a seat in the Parlement of Paris, nor did the principality of Poix (see below); so in 1767, Louis XV created a new duchy-peerage called Poix, and confirmed the earlier title of ‘Prince of Poix’, though still with only vague legal ramifications. Late in life, the 1st Duke of Mouchy and Duke of Poix was appointed Governor of Guyenne (1775), as well as Marshal of France, and resigned the post of Governor of Versailles to his son and heir, who became known as the ‘Prince of Poix’ (1778).

The castle and village of Poix in the southwest corner of Picardy (near the border with Normandy) was the centre of a lordship as early as the eleventh century. Like some other powerful lordships in border zones, its lords started to use the title ‘prince’ (in this case as early as 1153), a title suggesting they had no other superior lord in the feudal hierarchy; this was even confirmed by Louis XII in 1504. For nearly four hundred years, Poix was held by the Tyrel family, who had an interesting role in the trans-national Anglo-Norman story: an early Tyrel lord accompanied William of Normandy in the Conquest of England and was rewarded with lands, especially in Essex; Gautier II (aka Walter Tirel or Tyrrell) was a companion of William II of England and was accused of complacency in the ‘accidental’ murder of the King while out hunting in the New Forest in 1100. Walter fled to France and denied any guilt, and ultimately the family returned to royal favour, with Walter’s grandson Hugh Tyrel taking part in Henry II’s invasion of Ireland in the 1170s. When the Tyrels died out in 1417, the Principality of Poix passed via various people until it was held by the Créquy family who elevated the property into a duchy (with the name ‘Créquy’) in 1652. It then passed by descent and purchase to Philippe de Noailles, who became, as we’ve seen, ‘Prince of Poix’. The ancient castle by now was a ruin, and today survives as a farm with buildings rented out for wedding receptions.

Meanwhile, Philippe de Noailles’ other title took its name from the lordship of Mouchy-le-Châtel, also northwest of Paris in Picardy. It too was a very early barony, from about 1100, held by a local family, Trie, for many centuries. In the 1630s it passed to the family of Louise Boyer, who, as above, married into the Noailles family in 1645. The ancient château from the twelfth century crumbled over the centuries, but was restored in the nineteenth century as part of the great neo-gothic revival—and inspired the same architects when they were designing Waddesdon Manor in Buckinghamshire, England. Severely damaged in the Second World War, the remains of the once very grand Château de Mouchy were demolished in 1961, leaving only a round tower and terrace, along with family tombs. A short distance to the west, one of the villages that was part of the estate, Longvillers, that was situated on the important road from Paris to Calais was renamed ‘Noailles’ by the Duke of Mouchy in about 1750. He opened a new market here, and over the next century the his descendants developed the town as a place of industry. In Paris, the Duke established his residence on the rue de l’Université, in the faubourg Saint-Germain—this Hôtel de Noailles-Mouchy, with a very large garden, was later confiscated and incorporated into the buildings of the Ministry of War.

The 1st Duke of Mouchy had two sons. The younger, Louis-Marie, Vicomte de Noailles, married the daughter of the Duke of Noailles, then joined his brother-in-law the Marquis de La Fayette as a military volunteer in the American Revolution. Back in France, he retained some of this revolutionary fervour and was an avid member of the Constituent Assembly of 1790-91 (the body working to write a new constitution for France), even serving as its president in February 1791. But as the Revolution radicalised and targeted aristocrats—whether they were supporters or not—he emigrated in 1792. His wife did not and she was executed in the Terror in 1794. The Vicomte later returned to France and joined the navy, and was killed in battle versus the British near Cuba in 1804.

His older brother Philippe-Louis, Prince of Poix, took over their father’s roles: as Captain of the King’s Bodyguard from 1775 and Governor of Versailles from 1778. In his capacity as Captain of the Hunt of Versailles, in 1787, Poix built a hunting lodge adjacent to the Great Park, “La Lanterne”—probably named for the great light on top of the King’s menagerie nearby. In the nineteenth century, the pavilion was used by officers of the royal horse farm and stables; after the Second World War, it was the residence of the American Ambassador then the President of the National Assembly, before it became the official country residence for the Prime Minister of France, and since 2007, the President of the Republic.

The Prince of Poix supported the reforms demanded in the summer of 1789, but became disillusioned sooner than his brother and emigrated in 1790. His father and mother, the 1st Duke and Duchess of Mouchy, were both guillotined in the summer of 1794, alongside several other members of the family, as noted above. The new 2nd Duke of Mouchy returned to France in 1800, but was not returned to prominent posts until the restoration of the Bourbons in 1814: once more Captain of the Gardes du Corps and Governor of the Château of Versailles. He was formally created Duke of Mouchy in the peerage of France in 1817 (so, no longer relying on the Spanish creation), and died in 1819.

Charles, 3rd Duke of Mouchy, died relatively young in 1834, and was succeeded by his brother, Just, who had already had a prominent career as a supporter of the Napoleonic Empire: he married one of Tallyrand’s nieces in 1803 which connected him to the inner circle at court; was appointed Napoleon’s chamberlain in 1806 and a Count of the Empire in 1810. At the Restoration he was appointed Ambassador to Russia (1814-19), France’s key ally at this time. He lived only for a decade as 4th Duke of Mouchy and died in 1846.

Their cousin, Alexis, Count of Noailles, was more active in politics—the orphaned son of the executed Anne de Noailles and the war-hero Louis-Marie de Noailles (above), he grew up hating the Revolution and all it stood for. He joined the court in exile of Louis XVIII in 1810, the served as aide-de-camp to the King of Sweden (former Marshal Bernadotte) against the armies of Napoleon in 1813, and was appointed aide-de-camp of the King’s brother, the Count of Artois, in 1814. Artois was the leader of the very conservative royalist faction at court (the ‘Ultras’) and Count Alexis became one of his mouthpieces in the National Assembly as a deputy and a member of a very conservative group, the ‘Chevaliers de la Foi’ (the knights of the faith). He continued to support Artois when he succeeded as king (Charles X) in 1824, but lost influence in government (and his seat) after the conservative king was deposed in the July Revolution of 1830.

There’s not much to report about the 5th Duke of Mouchy (Charles-Philippe) who died in 1854, nor his son the 6th Duke (Antoine), who died in 1909. The latter was a Bonapartist politician, even after the fall of the Second Empire and into the Third Republic (and he married a Murat, so was distantly related to the Imperial family). His son and heir, François, Prince of Poix, died nine years before his father, but also made an interesting marriage, to Madeleine Dubois de Courval, heiress of a grand château of Pinon in Aisne (eastern Picardy). Badly damaged in the Great War, it was rebuilt in a very modern style, which brings us to the twentieth century.

The twentieth-century Mouchy branch was led by the 7th Duke (Henri), until 1947, then his son the 8th Duke (Philippe, d. 2011), and now the 9th Duke (Antoine), born in 1950. His son Charles, Prince of Poix, was born in 1984. The 9th Duke’s brother Alexis, Vicomte de Noailles, linked the family more closely to the former royal family itself through his marriage in 2004 to Princess Diane d’Orléans, daughter of the Duke of Orléans. Moving back one generation, the 8th Duke of Mouchy married Joan Dillon, daughter of the American ambassador to France (and later Secretary of the Treasury), widow of Prince Charles of Luxembourg (also a Bourbon through his father), and became one of the managers of her family business, Haut-Brion, near Bordeaux, one of the premier wineries in France.

Back another generation, we return to the brother of the 7th Duke, Charles, Vicomte de Noailles, and his wife, Marie-Laure. The daughter of the Bischoffsheims, Jewish bankers from Belgium, the new vicomtesse’s religion already would have scandalised some in French high society. But the couple’s eccentric lifestyle for years cultivated an amazing roster of artists, from Cocteau to Picasso to Man Ray, who gathered at their Villa Noailles at Hyères on the French Riviera. Built in 1923-25 in the ‘moderne’ or functionalist style, it also had a ‘cubist’ garden. Marie-Laure in particular had intimate relations with some of her protegés, described by some as ‘platonic affairs’ with mostly homosexual men. She died in 1970, and her husband eleven years later.

From Picardy to Provence and from Limousin to Versailles, the Noailles family has certainly left its mark on the history of France!

(images Wikimedia Commons)

J’aime bien votre style et les sujets abordés.

LikeLike

Merci!

LikeLike