I’ve been watching ‘Vikings’ on television again this summer, and always find it fascinating to see how Norwegian and Danish seafaring culture impacted the culture of the British Isles in the early medieval period. But this series, or the series ‘The Last Kingdom’, focuses almost entirely on the eastern and southern realms of Anglo-Saxon England: Northumbria and Wessex. Those who know something about the history of Scotland, however, know that Scandinavian power also extended over much of the northern and western parts of that kingdom, and even endured for several more centuries. One of the epic princely stories from this time period is that of a Viking warrior, Somerled, King of the Isles (d. 1164). From him descends one of the most powerful clans of Highlands and Islands of Scotland: the MacDonalds. These were entitled ‘Lord of the Isles’—though sometimes given title ‘prince’ or even ‘king’—whose territories at their greatest extent stretched from the Outer Hebrides to the Isle of Man, and on the mainland across the north of Scotland to Inverness, until it all came crashing down at the end of the fifteenth century.

After that, the successive chiefs of Clan MacDonald held no higher noble titles than ‘laird’ in the Scottish system, with the exception of one branch, Macdonnell, based in Ulster, which received an earldom (later marquessate), of Antrim, in the peerage of Ireland; and another received a barony, of Slate, also in Ireland. One line, Clanranald, made noises about being of ‘princely’ stock in the early eighteenth century when they supported the Jacobite pretender (and were given a barony, but only in the Jacobite peerage). Today, some of the Highland chiefs are referred to as ‘prince’ of their clan—so I have decided to include them as honorary members of this website on ‘dukes and princes’, as descendants of the genuinely princely Somerled, Prince of the Isles.

The thorny question, though, is whether Somerled was a Viking or not. Recent DNA tests have affirmed that his paternal ancestors were indeed Norse, but in his own time, the warrior-king thought of himself as part of the Gaelic community that stretched across the narrow channel between Ireland and Scotland, the kinship of the royal house of Dalriata. This was politically astute as he tried to balance his fragile independence between the far-off king of Norway—who still claimed to be sovereign in these parts—and the rising power of the Gaelic kingdom of the Scots, and the always feuding kingdoms of Ireland. Legends connected his ancestry through royal lineages of Ulster all the way back to Conn of the Hundred Battles, the legendary second-century High King of Ireland. Another motive may have been Somerled’s desire to unify the Gaelic Christian world under the leadership of the Monastery of Iona in the face of Latin Christianity taking over from the south and east.

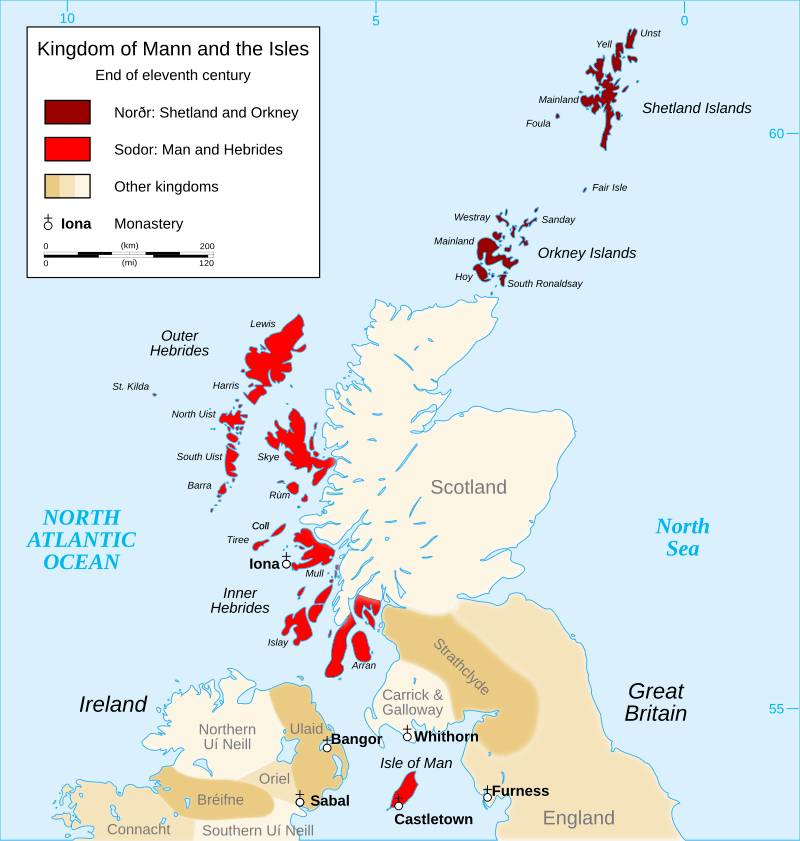

So his identity in truth was blended. His name is spelled either Somhairle in Irish or Sumarliði in Norse (‘summer traveller’). His descendants are known as Clan Somhairle. But where did he come from? Much of Somerled’s story is fragmentary and sometimes contradictory. He is said to have been born in Argyll, or maybe in Ireland (his father is given an Irish name: Gille Bride). He first appears in archival sources in 1153 during a rising of his Scots nephews against King Malcolm IV. It seems he had initially been serving in, or provided mercenaries to, the armies of King David I, who subjugated Argyll in the 1130s. He later fought against this King David’s grandson, Malcolm IV, because (it is conjectured) his sister married an illegitimate son of King Alexander I (who had been displaced by David I), and her sons were thus trying to regain their inheritance. This probably spurred his own ambitions to create an independent kingdom of his own in Argyll and the Western Isles (Islay, Skye, Mull, Lewis, etc). These ‘southern isles’ (in contrast to the northern isles of Orkney and Shetland) were called in Norse the Suðreyjar, or the Sudreys in English (or even ‘Sodor’). In Gaelic, the Kingdom of the Isles was called the Rioghachd nan Eilean.

Somerled’s main seat was his castle on the island of Islay: Finlaggan. This remained the princely headquarters for his descendants the Lords of the Isles until the 1490s. It was located on Eilean Mór, ‘the Great Island’, in Loch Finlaggan in the interior of the island. A stone castle was built in the thirteenth century to replace Somerled’s wooden fort. This island also had a church, Kilfinlaggan, once a monastery—possibly founded by an Irish monk, Saint Findlugan, in the seventh century. Both are in ruins today. A smaller island in Loch Finlaggan, Eilean na Comhairle (‘Isle of the Council’), served as the administrative centre for the Kingdom of the Isles.

The war Somerled fought in the 1150s was also over another significant island, the Isle of Man, which had been ruled by a dynasty of Norsemen since the 1070s: the Crovans. Norsemen had created chieftaincies and small kingdoms here since the ninth century. Their lords were called the Ivarids (or Uí Ímair in Irish), ‘the dynasty of Ivar’, which has led some to believe they descended from the ferocious legendary Viking warrior Ivar the Boneless who invaded England with his ‘Great Heathen Army’ in 865. But it may simply be a different Ivar who lived about the same time. He founded a dynasty that ruled variously in York and in Dublin for the next two centuries. Ivar hailed from Lochlann, the Irish term for Norway (or for the Norwegian realms in western Scotland). In 990, the Jarl of Orkney took direct control over the Western Isles in the name of the King of Norway, and installed a local jarl, Gilli, as viceroy. Norse kings in Dublin extended their rule over the Western Isles in the eleventh century. One of these, Godred Crovan (which could mean ‘whitehand’—or else a corruption of Cuarán, the name of an early King of the Isles), fought for the Viking king Harald Hardrada at Stamford Bridge, 1066, then fled to the Isle of Man where he proclaimed himself king by the end of the 1070s. He was later ousted and died on Islay in 1095.

One of the most intriguing moments of Norse-Scottish history occurred in about this time, in 1093, when King Magnus III of Norway came to the Western Isles to re-establish direct rule and to potentially conquer the mainland from the Scots, famously pulling his longboats over the isthmus of Kintyre to prove that this narrow peninsula should indeed be considered an island, and therefore legally his. In 1098, the king of the Scots officially renounced claims over the islands (and did include Kintyre).

One of the Croven kings of the Isle of Man, Olaf Godredson (Óláfr Guðrøðarson), ruled for a long time by Viking standards (1112-1153). In about 1140, Somerled married his daughter, Ragnhild Olafsdottir. Olaf had used this marriage as part of his anti-Scots coalition (with Fergus of Galloway, and even Stephen of Blois, king of the English), and also sought Norse support by sending his son Godred to Norway to do homage, 1152. Olaf was assassinated in 1153 by his own kin from Dublin while Godred was on the return voyage. The son found maintaining his father’s realm difficult, and he was pushed out of Man by Somerled, on the encouragement of local leaders. Somerled installed his son by Ragnhild, Dugall, on the Manx throne.

Castles from this time period on the Isle of Man include the main fortress built by Norse princes in the capital Castletown on the south-eastern side of the island, now called Castle Rushen, and Peel Castle on the western side, facing Ireland. Rushen’s central square tower was built in the tenth century then significantly augmented in the early fourteenth century when Man was captured by the Scottish kings. Peel Castle has a stone round tower from the eleventh century that survives, but the old wooden fort was replaced, like Rushen’s walls, in the early fourteenth century—though in this case with distinctive red sandstone. Peel Castle was the seat of the bishops of Sodor and Man until the eighteenth century, whereas Rushen was privately owned by the Stanley family as Lords of Man. Both were taken over by the British Crown in the eighteenth century. Though not part of the United Kingdom, the British monarch is still today the ‘Lord of Man’.

The complicated succession war in which Somerled had intervened in Scotland and in Man also involved the MacLochlans of Tyrone and the O’Connors of Connaught in the north of Ireland. The deposed Godred Olafson himself tried to take the Kingdom of Dublin in 1155. By 1156, Somerled abandoned the cause of his Scottish nephews and focussed instead on Man. There was a great battle off the coast of Islay in January 1156 and neither side could claim a victory. Somerled and Godred therefore initially divided the realm, but by 1158, the latter was driven out, and Dugall confirmed as King of Man. Somerled himself took the title King of the Isles (rex insularum, or in Irish rí Innse Gall), which included the Western Islands (the Outer and Inner Hebrides, but also the islands in the Firth of Clyde (Arran and Bute), as well as Argyll, Kintyre and Lorne on the mainland. He then made peace with Malcolm IV by 1160. But in 1164, possibly during another invasion of Scottish territory, he was killed at the Battle of Renfrew, south of Glasgow. He was probably buried on Iona, in the chapel he founded, Saint Oran’s.

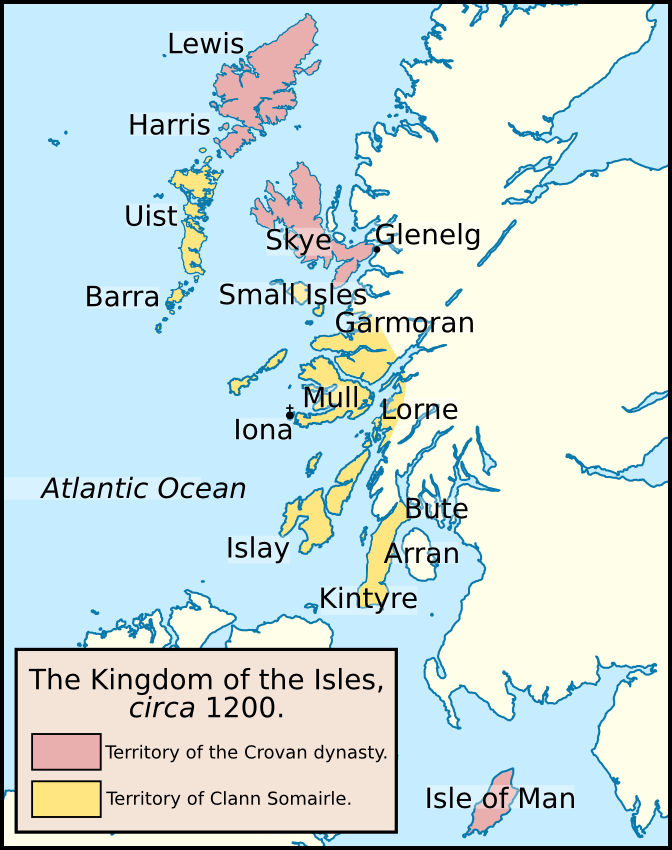

Dugall mac Somairle only held on to Man for about a year, before it was taken back by his mother’s family the Crovens, with help from the King of Norway. The Kingdom of the Isles was thereafter divided: the northern Hebrides (Lewis, Harris, Skye) and the Isle of Man returned to the Crovan Dynasty, while the southern Hebrides (Mull, Islay) and the mainland territories were retained by Clan Somairle.

The Crovan Dynasty continued as kings of Man until 1265. This was just two years after the great Battle of Largs, the last attempt of a king of Norway to keep control of western Scotland. Alexander III defeated Haakon IV at a small town on the coast of Ayrshire and ended five hundred years of Viking incursions. The 1266 Treaty of Perth transferred the Hebrides and Man to the Scottish Crown.

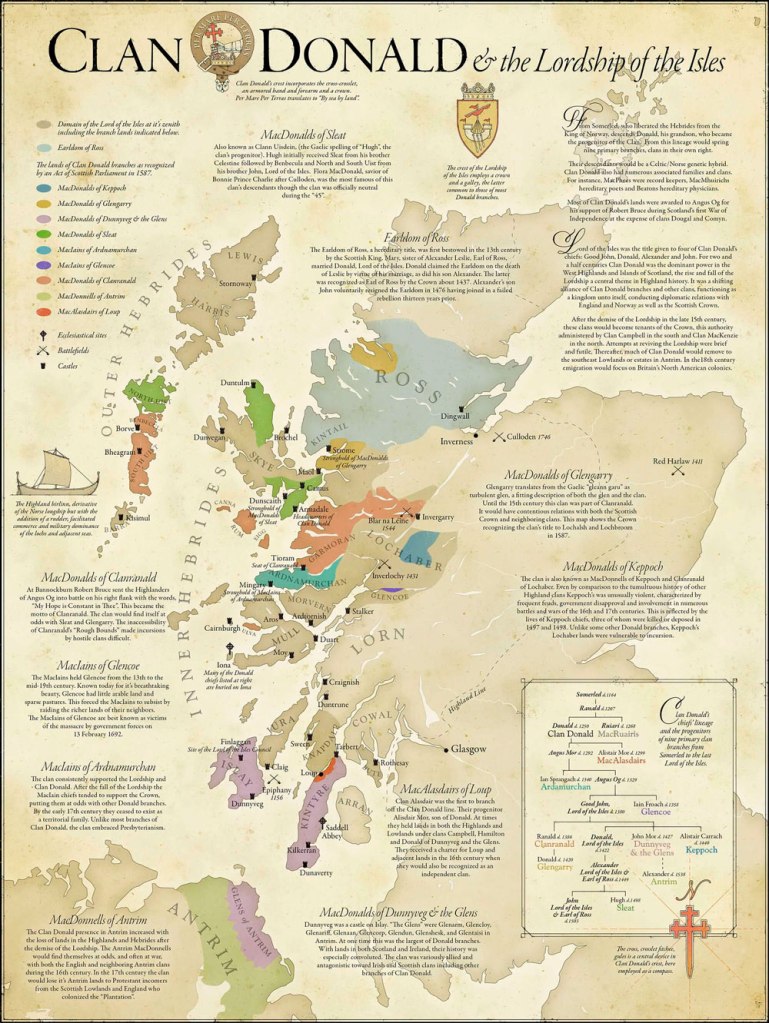

Of the sons of Somerled, facts are unclear, but it appears that Dugall (Dougall or Dubgall) received Lorne and Argyll, Angus got the northern Hebrides, and Ranald (or Ragnall) got Kintyre. Somerled’s daughter, Bethoc, was Prioress of Iona. Ranald asserted himself with the title ‘King of the Isles and Lord of Kintyre’, but as was so common in ruling dynasties of the period, Angus challenged this supremacy, and though Ranald was killed in about 1192 (or forced into a monastery), ultimately Angus and his sons were killed by Ranald’s sons in 1210. So two main branches emerged: the MacDougalls on the mainland (Argyll and Lorne) and the MacDonalds (named for Ranald’s second son, Donald or Domnall) in the islands. A third clan, Clan Ruaidri, descended from Ranald’s elder son, held Uist, Barra and some parts of the mainland; they died out in the 1340s. The MacDougalls fell from prominence after backing the wrong horse in the Scottish Wars of Independence (1290s-1320s) and their lands were redistributed to Stewarts and Campbells. Their seat has long been (and remains today) Dunollie Castle near Oban—the old fortress is a ruin, so they moved into a newer house next door in the mid-eighteenth century. Dunstaffnage Castle was their other famous stronghold, but it was lost with many of their other lands in 1309.

It is the line of Donald, the MacDonalds, that this blogpost will follow. Today Clan Donald is represented by four lines, with four clan chiefs: Macdonald of Macdonald, Macdonald of Sleat, Macdonald of Clanranald and Macdonald of Glengarry (plus many, many sub-branches). The founder was Donald, son of Ranald. He was possibly named for his mother’s clan, if she was indeed Fonia, daughter of William, Earl of Moray, son of King Duncan II—since Donald/Domnall was a name commonly used by the royal family. It comes from Gaelic dumno-ualos ‘world-ruler’ (in contrast, Ranald is not Gaelic in origin, but Germanic, from Norse Rögnvaldr, ‘ruler’s counsellor’). The facts of Lord Donald’s life are even shakier than those for his father and grandfather. He was possibly the subject of a story about a miracle escape from a Manx prison thanks to the intervention of the Virgin Mary in 1249, and probably died around 1250. He had two sons, Angus (Aonghus) Mór, Lord of Islay, and Alasdair, Lord of Kintyre. From the latter descends Clan MacAlister.

Aonghus mac Domhnaill was the first to bear the surname that became ‘MacDonald’. As a vassal of the King of Norway he had participated in the war against the Scots in the 1260s, but as that failed after Largs, he submitted to the King of the Scots, 1264, and the Isles, as seen above were formally annexed to Scotland. He therefore integrated into Scottish politics, for example, attending a council that met at Scone in 1284 to recognise Princess Margaret as heir to the throne. But he also involved himself in Irish politics, helping his kin defend versus the expansion of Anglo-Irish power in the north (and marrying his daughter to an O’Donnell, king of Tyrconnell). He had three sons: Alasdair Og, Lord of Islay, Aonghus Og and Eoin (Og means ‘the younger’). The last of these was founder of the line of MacDonald of Ardnamurchan. The eldest, Alasdair, held on to Kintyre, Jura and other small islands, and sometimes used the title ‘Prince of the Isles’. He married a MacDougall cousin and made claims on their territories, and supported King Edward of England in his attempts to subjugate Scotland after 1292. He was killed in 1299, and the MacDonald succession was unclear: his sons seem to have been excluded and became mercenaries in Ireland; his brother Aonghus took over instead and continued the feud versus the MacDougalls. Aonghus supported the rise of Robert the Bruce by about 1306 and was rewarded with his rival’s lands on the western coast (Lochaber, Ardnamurchan and Glencoe). He fought with the Bruce at Bannockburn, 1314, and perhaps campaigned in Ireland with his brother Edward, 1315-18 (and maybe was killed there).

Aongus Og mac Domhnaill had two sons. The younger, illegitimate, was Eoin Fraoch (‘snarling’), who founded the line of MacDonald of Glencoe—well known from the song about the famous massacre of 1692, when Clan Campbell carried out orders from William III to bring to heel the disloyal, Stuart-supporting, MacDonalds. The older son, also called Eoin or Iain (John), is seen as ‘Lord of the Isles’ in a document from 1336, though some near contemporaries did call him ‘king’: Rí Innsi Gall. He was courted by one faction in the ongoing succession wars of Scotland and gained the islands of Mull, Skye, Lewis and others for his clan (later confirmed by King David II). He then added the lordship of Garmoran on the mainland, through marriage to a MacRory, with the castle Tioram (‘Dry Castle’), an island in Loch Moidart that controlled access to Loch Shiel (also called Dorlin Castle). It too was said to have been built originally by Somerled, and eventually became the seat of the Clanranald branch of the family (below). Iain MacDonald’s bride was Lady Margaret Stewart, daughter of King Robert II. His new royal associate pressed him to disinherit his sons from his first marriage, but he was given the large Lordship of Lochaber as an incentive. By the time of his death in 1386, MacDonald power was nearing its high point. He controlled much of the western mainland and all of the Western Isles, including Iona, and was buried there.

Iain’s elder son, by the first marriage, was Ranald, Lord of Garmoran. He founded the lines of Clanranald and MacDonald of Glengarry (to which we will return). The younger sons, by Princess Margaret, were Donald, Lord of the Isles, and Iain, Lord of Dunyvaig. The latter rebelled against his brother in 1387, lost, and was exiled—he later served the English kings Richard II and Henry IV in their Irish affairs. His descendants were the MacDonalds of Dunyvaig. Dunyvaig Castle itself was another of those built by Somerled in the twelfth century, on the other side of Islay, on Lagavulin Bay. After the confiscations of the MacDonald castles of the late fifteenth century, it fell into disrepair, then was rebuilt when it was restored in 1545, as the seat Dunyvaig line (aka Clan Donald South, later earls of Antrim; see below). Surrendered to the Crown in 1608, it was given to the Campbells in 1647 and soon pulled down.

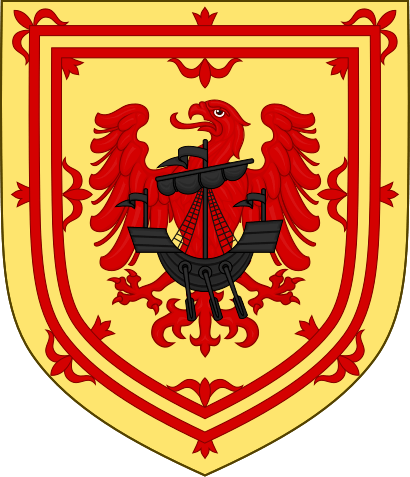

Donald MacDonald of Islay, Lord of the Isles, shifted the focus of the clan more towards the Kingdom of Scotland. As a grandson of King Robert II, he stressed his royal blood, and added a tressure to his arms (the same decorative ‘frame’ that is used in the Scottish royal arms). In the late 1390s, he started to encroach on territory on the mainland: Ross and Badenoch, lands of one of the branches of the House of Stewart. By 1395, he had taken Urquhart Castle, one of the most famous in the Highlands, a royal castle on Loch Ness in the Great Glen. This helped in his march towards conquering the Earldom of Ross, which controlled much of the far north of Scotland. In 1402, its last Earl (Alexander Leslie) died, and his sister Mariota, who was married to Donald, made claims on the vast territory. By 1410, MacDonald had taken Dingwall Castle, seat of the earldom—and deriving its name from the Norse Þingvöllr, meeting place of the ‘thing’ or assembly— on Cromarty Firth on the east coast of Scotland. 1411 saw two big battles: between clans MacDonald and McKay for dominance of the north; and against the Duke of Albany—Robert Stewart, Donald’s uncle, but also regent to his other nephew, King James I—and the Earl of Mar (Alexander Stewart). The latter battle was known as ‘Red Harlaw’ due to its savagery. Donald was victorious in all of these and the Crown recognised his possession of the Earldom of Ross. But in 1415, Albany retook Dingwall and assigned the earldom to his son John—John spent most his time fighting in France, and when he died there in 1424, Ross was uncontestedly in the hands of the MacDonalds. The ancient province of Ross, stretching from coast to coast, may have taken its name from the Norse word for Orkney (Hrossey, ‘horse island’), or—and more sensibly to me—from Gaelic for ‘headland’, referring to the great rocky cliffs near Dingwall. It had been an earldom from at least the twelfth century.

By this point, Donald, 2nd Lord of the Isles, had died and was succeeded by his son, Alexander, 3rd Lord and now 10th Earl of Ross. His brother Angus was created Bishop of the Isles, in 1426. This diocese, covering the Western Isles from the Hebrides to Man, is sometimes called Sodor, taking its name from that ancient Norse word for the southern isles (see above). It was created in about 1130; after 1387 it was divided and Man was ruled separately (and the diocese was abolished altogether in 1689). About thirty years after his death (c. 1440), Bishop Angus I was succeeded as bishop by his son Bishop Angus II.

Earl Alexander MacDonald continued his father’s struggle against the Duke of Albany, and thus supported James I in the re-taking of power from his uncle in 1425. By 1428, however, King James asserted Crown rule over the far too independent MacDonalds—he summoned the northern clans to his court at Inverness and arrested many of their chiefs, including Alexander and his son John. When he was released in 1429, Alexander returned with an army and burned Inverness to the ground. He was then defeated after a major battle, and formally submitted to the King at Holyrood Abbey in Edinburgh, then sent back to prison, now at Tantallon Castle on the Firth of Forth. The King and his chief ally in the north, the Earl of Mar, took over much of the MacDonald power. Earl Alexander was released in 1431, but his independent power and his enmity with the King had ended. In fact, when Mar died in 1436, Alexander was easily re-confirmed as Earl of Ross, and restored to Dingwall, Inverness, and even more lands. And in 1437 he was named Justiciar of Scotia, the highest Scottish official for the northern parts of the Kingdom. He died at Dingwall in 1449.

Alexander’s three sons from three marriages divided much of the patrimony. John of Islay, 4th Lord of the Isles and 11th Earl of Ross, was recognised as the ‘MacDomhnaill’, that is, the Chief of Clan Donald; while his brothers founded separate lineages: MacDonald of Sleat and MacDonald of Lochalsh. The latter was in fact the eldest son, Celestine, but Lochalsh was a significant lordship on the mainland, so seemed a good compensation for losing the overall headship of the family. Sleat was on Skye, and the lineage based here, founded by Hugh (or Ùisdean), was also called ‘Clan Donald North’ (we’ll return to them below).

Earl John returned his family’s power centre from Dingwall to the Western Isles; he held his court at Castle Ardtornish in Morvern. Located across the sound from Mull, at the southern opening of the Great Glen, it had been a hub of sea lanes since the time of Somerled, and one of the main MacDonald bases since the mid-fourteenth century. By the sixteenth, it was given by the Crown to the MacLeans; abandoned since the late seventeenth century, today Ardtornish belongs to the Campbells of Argyll.

The Lord of the Isles made war on the Scottish king once more in the 1450s, joining the rebellion of the Douglas Clan. He retook Urquhart Castle and the city of Inverness, and kept these when he made peace with James II in 1455. But in 1461, he made a deal with King Edward IV of England, who was annoyed that James III was harbouring the recently deposed Henry VI. The secret ‘Treaty of Ardtornish-Westminster’ of February 1462 stipulated that the MacDonalds would be loyal to England, if Edward would partition Scotland between Clan MacDonald and Clan Douglas—roughly north and south of the Forth of Firth. The Earl’s forces advanced under leadership of his illegitimate son Angus Og. But soon backed down. In about 1475, the King of England revealed this secret treaty of 1462 to the King of Scots, so the Lord of the Isles was summoned to the Scottish Parliament. He failed to appear, and was declared forfeit of this titles. He made peace with the King in 1476, but lost the earldom of Ross and the lordships of Skye and Kintyre, but kept the Outer Hebrides. John’s son Angus revolted, ejected his father from the clan and started a civil war. Early in the 1480s, Angus defeated his father off the coast of Mull—a place still called Bloody Bay.

Angus MacDonald solidified his hold on power by marrying the daughter of the first Earl of Argyll, Colin Campbell. He was murdered, however, by his Irish harper in 1490. His father John tried to take over the Lordship of the Isles by giving that title to his nephew Alexander of Lochalsh. He tried also to retake the Earldom of Ross, but was defeated by the Mackenzies at the Battle of the Park (c1491), west of Dingwall. In 1493, King James IV formally ended the independence of the Lordship of the Isles, by assuming the title for the Crown directly. The title is still given to the heir to the throne—so today William, Prince of Wales, is also the Lord of the Isles. Meanwhile, the earldom of Ross was now used as a royal dukedom for various younger sons of Stuart kings. In 1540, James V formally annexed Islay and the other islands of the Hebrides to the Crown of Scotland. John MacDonald spent the rest of his life a pensioner of the Crown in the Lowlands (dying in Dundee in 1503). The late Angus’s son, Donald (Domhnall Dubh), had been taken by his mother’s family, the Campbells of Argyll, and held as a prisoner for most of his life. He was released in 1543 and led a brief revolt versus the Earl of Arran, Regent of Scotland, with the support of Henry VIII, but he died in 1545 in Drogheda, Ireland. The main line of Clan Donald came to an end.

The leadership of Clan MacDonald passed to the line of Hugh of Sleat (pronounced ‘Slate’). Sleat is the peninsula that forms the southern ‘arm’ of the Isle of Skye; it takes its name from sléttr, Norse for ‘smooth/even’, and this area is indeed flat and more fertile than the rest of the island. Their seat was at Dunscaith Castle. This castle (‘fortress of shadows’) was named for an ancient warrior maiden, Scáthach (‘the shadow’), from Irish mythology. Built just offshore, it was held by the MacDonalds by the fourteenth century but fought over with the rival Macleans. This branch was confirmed in possessions on Skye by the Scottish king in 1476 as the overall lordship of the Isles was crumbling. Hugh’s son Donald Gallach was murdered in 1506—in a violent clash that involved his brothers contesting the succession. He was succeeded by his brother Gilleasbaig Dubh—who had a long career as a pirate and was also murdered, in 1520.

Much of the sixteenth-century history of Clan MacDonald of Sleat was an unending bloody rivalry with the MacLeods over control of Skye and Lewis, or feuds with other branches of the MacDonalds (which also developed into rivalries between Protestant and Catholic—for example the Clanranald line on South Uist were Catholic). Clan chiefs led piratical raids on neighbouring islands, or mercenary ventures to Ireland. The Scottish royal government was powerless to maintain order, but little by little the more loyal Clan Campbell became dominant in the west of Scotland. One by one the MacDonald chiefs submitted to the monarch and accepted legal charters of ownership over their land. The rivalry with the Campbells was re-activated in the Civil Wars of the 1640s when the MacDonalds supported the Crown and aggressively pursued the Convenanter Campbells. The tables were then turned with the loyal Campbells attacking the rebellious MacDonalds in the 1690s, notably at Glencoe. Naturally, the MacDonalds were therefore Jacobites in the eighteenth century, and on and on and on…

The Chief of MacDonald of Sleat—who was also, though not really recognised at the time, Chief of all of Clan Donald—continued to reside on Skye. Dunscaith Castle was abandoned to ruin in the early seventeenth century and they moved to Duntulm, at the other end of Skye on the northern peninsula, Trotternish. This castle was also from the fourteenth century, and was now expanded, but also abandoned in the mid-eighteenth century for a nearby modern house, Monkstadt.

Donald Gorm (‘Blue Donald’) succeeded as 8th Chief in 1616 and was created Baronet, of Sleat, in 1625. He was a Royalist who fought for Charles I, and died in 1643. The 4th Baronet, Sir Donald, was a Jacobite, and was created ‘Lord Sleat’ in 1716 (it is considered to be in the ‘Jacobite Peerage’, so legally never existed within Great Britain). This branch was the only one that did not later support the Jacobite uprising of 1745, so they kept their lands, while others had their estates confiscated. They were eventually rewarded: in 1776, the 9th Baronet (or 6th Lord Sleat) was created Baron MacDonald, of Slate, in County Antrim, in the Peerage of Ireland.

In 1814, the MacDonalds of Sleat added the surname Bosville, following a marriage with the heiress of estates in Yorkshire, including Thorpe Hall. The 3rd Baron, Godfrey, married Louisa, an illegitimate daughter of the Duke of Gloucester (George III’s brother), but their eldest son was born before the marriage. So the Bosville lands passed to the eldest son, while the second son received the baronial title and lands on Skye. In 1910 the elder son recognised retrospectively as capable by Scottish law of inheriting the baronetcy (and maybe, though purely hypothetically, the Jacobite title of Lord Sleat?). So today the head of Clan MacDonald of Sleat is the 17th Baronet, based at Thorpe Hall in Yorkshire, while the head of Clan Donald overall is the 8th Baron MacDonald, based on Skye.

In 1947, Alexander, 7th Baron MacDonald, was formally recognised by Lord Lyon as the High Chief of Clan Donald, or ‘Chief of Name and Arms of MacDonald—and in a sense the ‘Prince’ of the House of Somerled. He was further recognised by the Crown through his appointment at Lord Lieutenant of Inverness-shire in 1952. The 7th Baron was succeeded in 1970 by his son Godfrey. Until the 1920s, this branch of the family was based at Armadale Castle, on the southeast side of Skye, where the ferry comes in from Mallaig on the mainland. The mansion was built in the 1790s and given an extravagant neo-gothic tower in the early nineteenth century. Abandoned in 1925, it is now a ruin, but the gardens are maintained and are host to the Clan Donald Centre and the Museum of the Isles. The 8th Baron had sold this estate to a family trust in 1972, and moved his family to Kinloch Lodge, a small whitewashed former farmhouse and later hunting lodge, a few miles up the coast. It is run today as a luxury hotel. The 8th Baron MacDonald, Chief of Clan Donald, worked in local government in Scotland in the 1970s-80s. His ‘crown prince’ is his son Hugo (b. 1982).

There were, and are, many junior branches of Clan Donald, the heirs of Somerled, Lord of the Isles. Of these, two stand out in history and were given noble titles: MacDonnell of the Glens in Ireland, and MacDonald of Clanranald in Scotland.

In the sixteenth century, the head of the Irish branch (‘Clan Donald of the South’) was also the Laird of Dunyveg (see above), retaining the familial link across the sea with Islay. They were also called MacDonnell of ‘the Glens’, the nine valleys in the northernmost part of County Antrim, with their seat in Glenarm (one of the nine), which they had inherited in the late fourteenth century. Many members of this branch migrated to Ireland in the 1520s-30s, causing unrest in an already unsettled area. They were encouraged to move by James V, who delighted in unsettling the regime of his uncle Henry VIII; but were checked by English forces in a pitched battle in 1539 at Belahoe (Ballyhoe), County Meath.

The 6th Laird of Dunyveg’s younger brother, ‘Sorley Boy’ (Somhairle Buidhe, or ‘Somerled the Blonde’) MacDonnell, became one of the greatest warrior chieftains of the north of Ireland in the latter half of the sixteenth century. In 1559, he defeated a family who had long dominated the northern coast of Ulster, the MacQuillans, and took their stronghold, Dunluce, as his own. Dunluce Castle had been built on a great rock jutting out into the sea in the thirteenth century. Sorley Boy also took over their title, Lord of the Route—the name for this coastline. Dunluce was abandoned by the family in the 1690s and fell apart, as the family had shifted their seat to Glenarm Castle in the 1630s.

The 1560s-80s was a time of constant conflict with the English crown, or with the other powerful lords of Ulster, the O’Neills and the O’Donnells (see here for some of the turbulent history of the O’Neills). But marriage alliances were forged with both of these: Sorley Boy, Lord of the Route, married Mary O’Neill, daughter of the Earl of Tyrone, while her half-brother (and rebel leader) Shane O’Neill married a MacDonnell niece, Catherine. Catherine’s sister married Hugh O’Donnell, King of Tyrconnell—so it was all in the family. Eventually, Sorley Boy made formal submission to Queen Elizabeth in 1586 and was re-granted his lands as fiefs of the Crown. He died in 1590 and was buried in the family necropolis at Bonamargy Friary near Ballycastle, on the bit of the coast of Antrim closest to Scotland.

Sorley Boy had a number of nephews who were now both lords of the Glens and of the Route. They also continued to maintain a presence across the strait in Kintyre, so were interestingly both Scottish and Irish. After 1615, however, they were deprived of their Scottish lands by the Campbells acting on behalf of James VI. The senior line died out in 1626, so Sorley’s son, Ranald (or Randal) MacSorley MacDonnell, succeeded as the ‘Lord of the Route and the Glens’. He was—after the ‘Flight of the Earls’ of 1607, in which most of the senior Irish chiefs fled abroad rather than submit to English rule—the seniormost Gaelic nobleman in Ulster. His willingness to submit to James VI of Scotland, now James I of England, got him an appointment on the Privy Council of Ireland and the post of Lord Lieutenant of Antrim in 1618, with the new title, Viscount Dunluce. In 1620, he was created Earl of Antrim. Yet he remained a Catholic in this era of the Protestant plantations of Ulster.

His son, the 2nd Earl of Antrim, also called Randal MacDonnell, was a Royalist, and a regular attendee of the Stuart court in London. His wife, the widow of the royal favourite the Duke of Buckingham, was herself a favourite of the Queen, so Antrim’s standing was high. As tensions rose against Charles I in the late 1630s, he proposed an invasion of southwest Scotland using his (Catholic) Irish tenants against (Protestant) Scots (and hoping to regain his family’s lost lands in Kintyre). This invasion never materialised, but did further damage the reputation of Charles I in Scotland. His support for the Crown in the next Irish phase of the Civil Wars earned him the even higher title of Marquess of Antrim, 1645—but he was later tried for suspected collusion with the Cromwellian regime.

The Marquess had no sons, so this title became extinct in 1682. The earldom of Antrim, however, continued to his brother and his descendants into the eighteenth century, and was recreated in 1785 for the 6th Earl with a special clause allowing female succession. Antrim was then again a marquisate briefly from 1789 to 1791. Thereafter the earldom passed into the Kerr family of Lothian, who took the name MacDonnell. Today they are represented by the 10th Earl of Antrim, and their seat is still Glenarm Castle in County Antrim. They also maintained a grand townhouse in Merrion Square in Dublin, Antrim House, but it was torn down in the 1930s.

Back in Scotland, the line known as Clanranald (founded by Ranald, 2nd son of Iain, Lord of the Isles, above), continued to maintain the original lands of the MacDonalds in the Western Isles. Their main seat was Castle Tioram, on the mainland in the district of Lochaber. But several chiefs were buried at Howmore on South Uist (one of the Outer Hebrides), and not far away was the birthplace of another famous member of this branch of the family, Flora MacDonald (of ‘Skye Boat Song’ fame). A later seat was also on South Uist, Ormacleit, built in the early eighteenth century but destroyed soon after the Fifteen, and the seat moved to Nunton (Baile nan Cailleach, ‘settlement of the nuns’), on Benbecula, the smaller island between North and South Uist, from which Bonnie Prince Charlie had to be smuggled, ‘over the sea to Skye’.

In the early seventeenth century, Donald, 11th Chief of Clanranald, was the first to try to settle affairs with the Scottish crown and end a century of feuds and piracy. He met royal commissioners on Mull and agreed to submit to rule of law in return for debt relief. His son the 12th Chief ‘ruled’ for fifty years and was a chief supporter of the Royalist cause in the Highlands in the 1640s. But like the others, their royalism translated into Jacobitism in the eighteenth century: the 14th Chief (Allan) died in the Fifteen after being mortally wounded at Sheriffmuir. The 15th Chief, Ranald, was created ‘Lord of Clanranald’ by the Old Pretender in 1716—he survived and died unmarried in Paris in 1725. The clan lands were confiscated, but restored to his cousin and heir, the 16th Chief, Donald, of the Benbecula line. The 17th Chief did not support Bonnie Prince Charlie in the Forty-Five, but his son (and eventually the 18th Chief) did: this Ranald was one of the first to join the rebellion and raised significant troops at Culloden, after which he too escaped to France, and died there in 1776.

Another MacDonald worth mentioning here, in the context of late eighteenth-century France, is Jacques-Etienne MacDonald, whose father Neil MacEachen MacDonald, had been an early supporter of Bonnie Prince Charlies and received him at his home on South Uist in 1745 after Culloden, and helped him escape to France. Jacques-Etienne was born and raised in France, and became a Marshal of France under Napoleon and Duc de Tarente (both in 1809), in recognition of his conquest of the Kingdom of Naples. But it is unclear whether the Marshal MacDonald was in fact a MacDonald—several sources say the family MacEachen were a line of Clan Maclean. In any case, his story will feature in a separate blog with the other Irish curiosity in French history, the Duc de Magenta, Patrice de MacMahon, President of France in the Third Republic.

By the end of the eighteenth century, poverty in the Highlands and oppression towards Catholics, convinced many hundreds of members of this clan to emigrate to Canada (Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island). The chiefs by this point were little help, as they—like other aristocrats—were keen to clear the people off their lands to make them more profitable for sheep. Ranald George, 20th Chief of Clanranald, was head of the clan for much of the 19th century. He married the daughter of an earl from the southwest of England, and was the same year elected MP for a borough in Devon (1812 to 1824). He sold off most of his Scottish estates, except the now ruined castle of Tioram. So his interests were clearly elsewhere. He was even nearly replaced as Clan Chief by the head of Clan Glengarry, Alexander MacDonnell (see next). He died in London in 1873 and was succeeded by his son Reginald, an admiral in the British Navy and Commander-in-Chief of the East Indies Station. The main line ended in 1944 with the death of the 23rd Chief, and passed to cadets of the Boisdale line: the 24th Chief, Ranald MacDonald, was recognised by the Lord Lyon in 1956 (and is the 10th Lord of Clanranald in the Jacobite Peerage).

Of the other clans that received a noble title (beyond ‘chief’), there were also the MacDonalds of Glengarry. Their chieftain was at one point one of the greatest landowners in the Highlands. Alastair Dubh, 11th Chief of Glengarry, was one of the leaders of the Jacobite rebellion of The Fifteen, and was created ‘Lord MacDonell’, 1716, by the Old Pretender. They took part in The Forty-Five as well, with the Glengarry Regiment being the largest contingent at the Battle of Culloden. After this, their lands were mostly confiscated, and the seat, Invergarry Castle, destroyed by government troops.

One of the most colourful men of the early nineteenth century in Scotland was the 15th Chief, Alexander (or Alasdair in Scots), the 5th Lord MacDonell in the Jacobite Peerage, who had tried to unseat the Chief of Clanranald (above) in 1824. He was a flamboyant character who always dressed in traditional kilt and maintained old traditions of always being accompanied and served by an entourage, always with a piper in tow. He attended the coronation of George IV in Highland dress and was said to have popularised that style all over Britain and stimulated the imagination of Sir Walter Scott. Yet traditionalist as he was, he too was equally guilty of his part in the Clearances, resulting in a mass exodus to Canada, Australia and New Zealand.

Indeed, the head of this branch today, the 24th Chief of Glengarry (or 13th Lord MacDonell) lives in Vancouver. Today there are MacDonalds all over the world—one of these who can come to prominence in recent years, and certainly in the world of dukes and princes, is Mary Donaldson, Queen of Denmark since January 2024. So in a sense, the Viking blood of Somerled has gone home to rule…

(images Wikimedia Commons)

WOW!!I’m speechless

LikeLike

Glad you liked it. I had fun researching it

LikeLike

Ive read your spew regarding the lineage of my family. I am King Robert Stuart and of the Royal House of Stewart. It is I that holds the Magna Carta and the Seat of Origin for the Crown and Throne of United Kingdom and the Constitutional Parliament as issued to me in the Royal Trust through the verified lineage of my family. Processed by Barrister to the Crown, Louis Watson, Esq. Confirmed through the House of Lords and Processed and Confirmed by the Chancery Court whom then forwarded the Trust to the International Court of Settlements because I am also seated as the Principal Officer / Representative of the Crown of the Dominion of Canada and am the Lawful Constitutional Principle and North American Monarch. The International Court of Settlements has Confirmed the granting of the Trust and it was forwarded to the American Federal Judiciary and was received and processed by U.S. Federal Court Justice Vincent Sherry presiding within the Silver Lake Trust Territory of the Kingdom of England situated on American Soil. I am also the Heir if Anna Mae MacDonald whom was also known as Anna Fisher and by the given name of Anna Prentis. I am what you call a Jacobite and I assure you we are not the Pretenders. In fact it was I whom signed the Authorization for Elizabeth to be seated in the instruction of my Parliament and it was I whom signed the Documents of Stewardship for Elizabeth to occupy sleeping quarters on the Palace grounds. I am also the bearer of the Crown of the Tudor Estare as issued to my Grandfather James by Elizabeth the first through her Assignment. So while you saw Elizabeth as a Queen let me assure you she was never the Queen . She was a Representative of the Crown. Yes. But the Crown I bear as King in Right and King by lawful Assignment. Please get your facts straight and stop spreading lues to defame my family aka the Jacobites. Otherwise I may not be so tolerant the next time I read your slanderous material.

sincerely,

King Robert Stuart / Stewart.

LikeLike

Hmmm. When you die, can I get your LP collection?

LikeLike