The names Farnese and Parma evoke a number of images from Italian and European history. The ‘Villa Farnese’ embodies the beauty and grace of the Renaissance palaces of the Roman countryside and of one of its chief patrons, the beautiful and graceful Giulia Farnese. The name Parma in contrast, beyond the most immediate associations we now have with ham—and rightly so—will remind English readers of one of the most famous speeches in English history, as the Spanish Armada approached the shores of England in 1588, and Elizabeth I rallied her troops at Tilbury with the cry: “…and think foul scorn that Parma or Spain, or any prince of Europe, should dare to invade the borders of my realm.” This ‘Parma’ was Alessandro Farnese, Duke of Parma, one of the great military leaders of the era.

The real founder of the family’s swift rise to the top of the social hierarchy of 16th-century Europe was Alessandro’s great-grandfather, and Giulia’s brother, another Alessandro Farnese, who became a cardinal in 1493, then in his mid-60s was elected pope (1534) and took the name Paul III. One of the great reforming popes, who launched the Catholic Reformation and the Council of Trent, the Farnese pope had initially been under the patronage of the infamous Borgia pope, Alexander VI—who was Giulia’s lover. But unlike Pope Alexander, Pope Paul was able to achieve something most papal families desired: a sovereign territory in which to permanently plant his family amongst the premier ruling dynasties of Italy.

The first of these semi-independent territories was the duchy of Castro, northwest of Rome in the borderlands between Lazio and Tuscany, created for his illegitimate son in 1537. Far grander was the duchy of Parma, across the Pennines in the province of Emilia, granted to the same son in 1545, and augmented with the neighbouring duchy of Piacenza. The Farnese family could now rival the other ducal families of northern Italy, the Medici, Gonzaga or Este, and they build grand residences in their capital cities to compete with these in genuinely princely splendour. They also constructed grand palaces in Rome and the Roman countryside to maintain their position in the hierarchy of the great aristocratic families of the Eternal City. Though they would eventually lose Castro in 1649, Parma and Piacenza continued to flourish as a small state, and the Farnese art collections grew to become one of the greatest in the world, until the dynasty itself died out in 1731, and its heiress took the inheritance to the Bourbons of Spain by her marriage to King Philip V. After 1748, a new Parma dynasty was born, Bourbon-Parma, which would rule Parma and Piacenza—aside from the major disruption of the Napoleonic era—until the unification of Italy began in 1859. The Farnese dynasty, as dukes and princes, only had a lifespan of about two hundred years, 1537 to 1731, but their legacy lives on in much of the architecture of Parma and Rome, and in the great Farnese art collections now housed primarily in Naples.

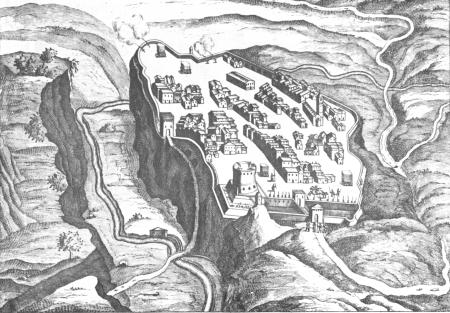

The Farnese family had its origins in the hilly lands to the north of Rome in the province of Latium (today’s Lazio) in the valley of the river Fiora which forms part of the boundary with Tuscany. This region features several almost perfectly circular lakes, the calderas of extinct volcanos, notably Lake Bolsena, on which one of the early Farnese residences, the Rocca Farnese in Capodimonte, beautifully sits. Most of the hills in this area are volcanic, and on the top of one of these tufa hillsides rose the castle and village of Farnetum, which gave its name to the Farnese family, sometime in the 10th century. It is suggested that the name comes from a local variety of oak tree known as the farnia. The town of Farnese remains a picturesque walled town. After the lands in Lazio were lost to the eponymous Farnese dynasty, the town and lordship of Farnese passed into the possession of the Chigi family (originally from Siena), who were created princes of Farnese (1658, for the nephew of the Chigi pope, Alexander VII), a title which they still hold today, though the property itself passed to the Torlonia princely family in the late 20th century. These princes will have their own separate blog post.

The earliest ancestors of the family, who claimed, like most grand noble houses of northern Italy, to be descended from ancient Lombard warriors, were condottieri, soldiers for hire, and they made their mark mostly leading pro-Guelph (that is, pro-papal) forces in the 12th and 13th centuries. They were rewarded with papal fiefs in proximity to the village of Farnese, notably Canino and Cellere, which, like Capodimonte, also feature buildings that still bear the family name: the Rocca Farnesiana (in Cellere) and the Castelvecchio dei Farnesi (in Canino). In the hills outside Canino, they acquired a former Benedictine monastery overlooking the river Fiora, the Castello dell’Abbadia, with its treacherous bridge, the Ponte del Diavolo—the ‘Devil’s Bridge’. This castle served as one of the primary residences of the family after they acquired the fief in 1430. Canino was later given as a principality to Lucien Bonaparte, brother of Napoleon, who is buried in the town chapel. The line of Bonaparte princes of Canino and Musignano (a neighbouring village), continued into the 1920s.

The most prominent early Farnese condottiero was Piero, who was employed as Captain-General of the Papal Armies, re-asserting Rome’s control over the city of Bologna in 1359, then Captain-General of Florence, leading its army to defeat the great rival Pisa in 1362. His nephew, also called Piero, was Captain-General of the Army of Siena, 1408, and waged a long-term vendetta with the rival noble family in this region, the Orsini. Two of his many sons founded the two main branches of the family, Castro and Latera, each with a duchy in the 16th century. We will return to the line of Latera below. The senior line would be founded by Ranuccio ‘il Vecchio’ on a castle (or castrum, castro) near Farnese and Canino, called Ischia di Castro.

Ranuccio Farnese also acquired the lordship of Montalto (de Castro), which is on the seacoast, and enjoyed the privilege of exporting grain without paying the normal tax to the pope. He too was a condottiero, but was astute enough to accumulate levels of debt (years of back pay) from the papacy instead of cash or fiefs, so that by the 1430s-40s he was himself one of the bankrollers of the papacy (a trick the Medici similarly performed to perfection!). Many of the fiefs he did hold from the papacy were given time limits for repayment, and when the popes did not pay, they became Farnese assets outright. Ranuccio was appointed Captain-General of Papal Armies in 1435, and consolidated his family’s hold over this part of the province of Lazio. He also ended the long and bloody feud with the Orsini by marrying his son Gabriele to Isabella Orsini in 1442. When he died in 1450 he was buried on a family tomb on an island (Bisentina) in Lake Bolsena.

Ranuccio’s younger son, Pierluigi, had made a different marriage: to Giovanna Caetani, from one of the leading aristocratic families of Rome, more firmly linking the Farnese to Roman high politics. The eldest of his two sons, Angelo, continued in the family tradition of military service to the papacy, but died before he reached 30, in 1494. By this point, however, a new star had risen for the family, Giulia, ‘la Bella Farnese’. She had been sent by her mother to Rome to be brought into society by the Caetani family and in 1489 was married to another Orsini (Orsino Orsini to be exact). While the details are patchy, it seems that through her new mother-in-law, Adriana de Mila, a cousin of the Borgias, Giulia became acquainted with Cardinal Rodrigo Borgia, and in 1493, when he was elected pope as Alexander VI, she rose to great heights as his mistress, and he installed her in a palace near the Vatican, which she shared—perhaps uncomfortably?—with his daughter Lucrezia. She made sure that her brother, Alessandro, was favoured by the Borgia pope, and he was indeed made a cardinal, in 1493, at 25, and a few years later, Bishop of Montefiascone and Corneto, the local diocese near the Farnese properties in Lazio.

Cardinal Farnese was not of course universally praised for his means of securing high church office: he was called ‘the Borgia-in-law’, and much worse. Like a good Roman aristocratic cleric of his day, he took a mistress, Silvia Ruffini, from a Roman noble house, and had four children between 1500 and 1510. His patron Alexander VI died in 1503, but successive popes were unusually generous in legitimising the Cardinal’s children so they could inherit the Farnese lands—especially important since, by 1512, the senior branch founded by Gabriele had died out. The new pope, Julius II, was no fan of the Borgias (or their clients), so perhaps as a means of getting Alessandro away from Rome, he promoted him to the bishopric of Parma, 1509, thus initiating the family’s connections to that city.

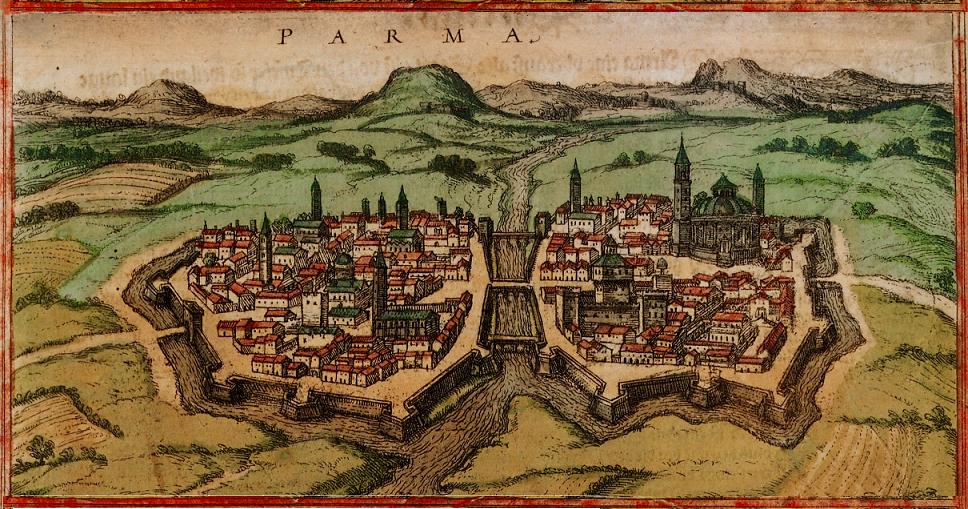

The city of Parma had grown up around a crossroads, important since antiquity—and possibly derived its name in antiquity from palma, a circular shield used by local Etruscan warriors. The famous Via Aemilia ran straight through it, connecting east and west, while the Via Claudia ran north and south, connecting Lombardy and the broad Po valley to the Apennine mountain passes into Tuscany and Latium. In fact, the main medieval route taking merchants and pilgrims from France and northwest Europe down to Rome ran through Parma. When Charlemagne and his Frankish lords extended their rule into Italy, they had established a count in the city to guard this important crossroads, and this county of Parma remained (loosely) a part of the Holy Roman Empire, though it later gained a degree of autonomy under its local bishops. The magnificent Cathedral was built in this time (completed about 1100), followed by an even more spectacular Baptistry later in the century, which serves as an important marker of the transition between Romanesque and Gothic architectural styles.

In the 15th century, Parma lost its independence, and was incorporated into the territories of the Sforza rulers of Milan. By the end of that century it found itself in one of most contested zones of the Italian Wars, fought by French, Imperial/Spanish and Papal armies. Parma was annexed briefly to the Papal States in 1512, then occupied by the French until it was returned again to Papal rule in 1521. Cardinal Farnese’s reign as bishop was in the middle of all this. But by 1524 he was back in Rome, where he became Dean of the College of Cardinals, and in 1534, rather surprisingly, was elected pope, as Paul III. Many electors thought due to his age and infirmity, his papacy would be a short, and they would thus have time to prepare a proper campaign for his successor. But he lived, and thrived, for another fifteen years. He began a campaign of bold activities we now call the Catholic Reformation (or the ‘Counter-Reformation’) right away, for example revising rules of papal governance in 1536, excommunicating Henry VIII in 1538, and approving the founding of the Society of Jesus (the ‘Jesuits’) in1540. Paul III also launched one of the largest reform projects, the Council of Trent, in 1545.

But from the perspective of dynastic history, Paul III was not a reformer at all. Almost immediately upon becoming pope, he appointed his son, Pier Luigi, as commander of papal armies and Gonfalonier of the Church, and two of his grandsons, both teenagers, as cardinals: another Alessandro Farnese and Guido Ascanio Sforza. He even made a cardinal of his former mistress’s legitimate son (who was, many thought, actually his own son), Tiberio Crispo. But following in the footsteps of previous Renaissance popes, the Farnese pope wanted to create a significant territory that his family could rule as princes and pass on for generations. Pier Luigi, a warrior like his Farnese ancestors, had already made a name for himself—and not necessarily a good one, known for his cruelty and ruthlessness—fighting for Venice and for Emperor Charles V (including the famous sack of Rome in 1527). In 1534, he was given the marquisate of Novara, part of Charles V’s Duchy of Milan. In 1540, Pier Luigi sealed this Imperial alliance by marrying his son, Ottavio, to the Emperor’s illegitimate daughter, Margaret of Austria. Margaret was already the widow (though only 15) of Alessandro de Medici, first Duke of Florence, who had been murdered only three years before. She brought as a dowry the lands of Penna in the Abruzzo and estates she was given by her father in Naples. Pier Luigi tried to solidify this imperial relationship even further by offering his daughter Vittoria to the recently widowed Emperor himself, but Charles declined.

On the papal side, in 1538, Paul III created a new duchy for Pier Luigi, formed from the various Farnese properties in northern Lazio, and gave it the name Castro. It would reach from Lake Bolsena to the sea, and would be formally a vassal state of the papacy, but de facto an independent state. A brand new capital city was built, called Castro, not far from the old main Farnese towns of Ischia and Canino. The Pope also added the neighbouring duchy of Nepi, which had been initially created for Lucrezia Borgia in 1499. In 1540, he also gave his son the confiscated duchy of Camerino, on the other side of the Apennines near Ancona.

Pope Paul also tried to balance his son’s pro-imperial leanings by sending Pier Luigi’s younger son, Orazio, to the court of François I in France. By the late 1540s it was understood that Orazio would marry the Dauphin’s illegitimate daughter, Diane de France, which he eventually did, with the proviso that he would be a ruling duke himself, not just a second son, by inheriting the Duchy of Castro.

The Pope decided that Orazio’s elder brother Ottavio would be compensated for Castro with something much grander: Parma. While the Emperor was busy dealing with Protestants north of the Alps, Paul III thought he would seize the moment and enfeoff his eldest son with the duchy of Parma, which, as seen above, had only fairly recently become papal territory. He added to it the neighbouring duchy of Piacenza, on the River Po. Like Parma, the city of Piacenza also had ancient roots, as the ‘pleasant place’ or Placentia in Latin. It too had been ruled by Milan in recent centuries, but was annexed to the Papal States in 1521. The gift of these duchies was done in 1545; in exchange, Pier Luigi agreed to give up Camerino and Nepi (and to cede Castro to Orazio). The new duke established himself in the ducal palace in Piacenza by 1546, with plans to build something more permanent in Parma. But he soon revealed himself to be a tyrant, imposing heavy taxes and curtailing the traditional independence of the local nobles and clergy. He swiftly made many enemies.

At first the Emperor approved of the creation of the twin duchies of Parma and Piacenza, since it would, after all, ultimately benefit his daughter Margaret, who would become a sovereign, not just the wife of a papal bastard. But by 1547, Charles V changed his mind, and thought Parma really ought to belong to the Duchy of Milan after all, so encouraged his governor there, Ferrante Gonzaga, to fan the flames of the unrest Pier Luigi was already creating in his duchies, and to back an assassination coordinated by representatives of the leading noble houses (Pallavicini, Landi and Anguissola). His body was hung outside a window of the palace in Piacenza.

This started the short War of Parma, 1551-1552, which did not play out as you might have expected. Paul III had initially made peace with Charles V by acquiescing to the loss of Parma and Piacenza in 1547. But his grandson Ottavio, did not, and retook the city by force—supposedly angering his grandfather so much he died of a heart attack in 1549. Ottavio now allied himself with his younger brother’s patron, his father-in-law the King of France (the former Dauphin, now King Henry II), since his natural enemy was the Emperor Charles V—who was of course Ottavio’s father-in-law. This is very confusing! This short war was fought between Henry II of France and Ottavio Farnese on one side, and Charles V and the new pope, Julius III on the other. In the end, Ottavio was restored to Parma and Piazenza (and also succeeded his brother Orazio as duke of Castro when he died suddenly, fighting in a French army in Flanders in 1553), and France became the chief ally and protector of Parma—which it remained (sometimes) for the next century and a half.

Before moving on firmly to the history of Parma and its dukes, we should stay in Lazio and look at properties—and two more cardinals. The eldest grandson of Pope Paul III, Alessandro, was made a cardinal when he was 14 in 1534. The younger brother Ranuccio was made cardinal at 15 in 1545, and though he held many benefices and administrative offices, and a lucrative commandery as a knight of Malta, he died at 35 before really making his mark.

Alessandro, however, rose right away, first as Vice-Chancellor of the Church (an office he held for over 50 years), then from 1538 as his grandfather’s principal secretary. By the 1540s, he was conducting much of the business and political affairs of the papacy. At first he was also used to solidify the Farnese family ties with the Habsburgs, as Cardinal-Protector of the Holy Roman Empire and of Spain from 1541; in return, Charles V named him Archbishop of Monreale in Sicily. But he also had French interests, as Papal Legate to Avignon from 1541 to 1565 (and he had a French mistress, Claude de Beaune de Semblançay, a lady-in-waiting to Queen Catherine de Medici, and a half-French daughter, Clelia). He sided with his brother in the War of Parma, so lost several of his Imperial benefices, but became instead an important channel of communication between France and Rome (though here too he gradually lost out due to the growing influence in France of Cardinal Ippolito d’Este). His clout rose again in Rome in the 1560s-70s, and he was a serious candidate for the papal throne in the conclaves of 1566 and 1572. As a grand old man, he was Dean of the College of Cardinals, from 1580 until his death in 1589.

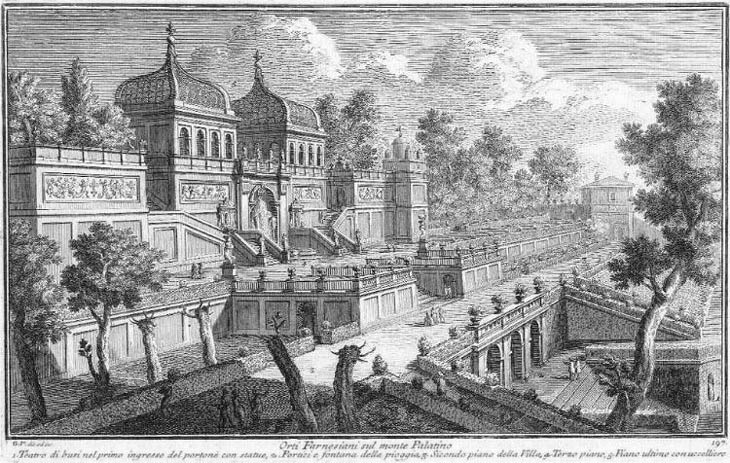

This second Cardinal Farnese’s main legacy are the buildings. He took over the residence in Rome his grandfather had built in the 1520s, the Palazzo Farnese, which he expanded in the 1530s, and laid out the Piazza Farnese. This is still regarded as one of the most beautiful squares in Rome, and, as is fitting for the long-term Franco-Farnese alliance, is now the seat of the French embassy. It was in the 17th century, the home of the huge Farnese art collection, but after the Farnese properties passed to the Bourbons, these were shipped to Naples, where they formed the collection of the new Capodimonte Museum.

Across the Tiber, in the more leafy suburb of Trastevere, the Farneses acquired a villa built earlier in the century by the wealthy Chighi banking family. This villa, famous for its Raphael frescos of ancient Greek myths, was renamed the Villa Farnesina. It later was the residence of the Bourbons of Naples when in Rome, but after the unification of Italy in the 1860s it became the residence of the Spanish ambassador. Now it belongs to the state and houses the Accademia dei Lincei.

Also in Rome, Cardinal Alessandro built a summer house and gardens on the slopes of the Palatine Hill (the Farnese Gardens, built in the 1550s), with different spaces devoted to pleasure or to botanical research. He sponsored the building of the main Jesuit church in Rome, the Gesù (in the 1560s), and chose it as his burial place.

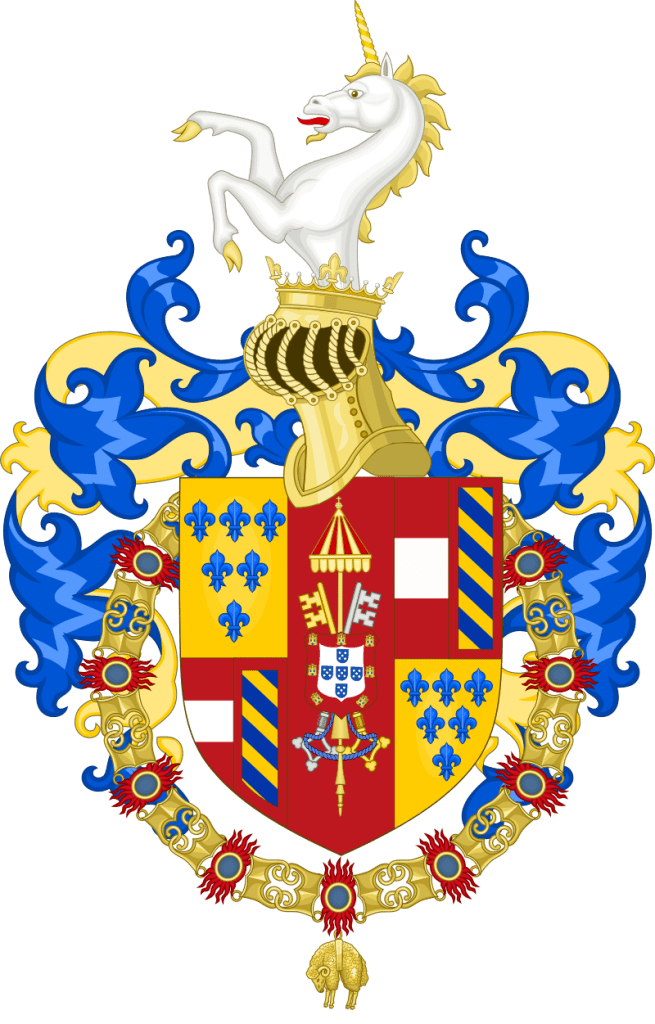

All over these buildings, you can still see the ubiquitous Farnese lilies (or gigli), which conveniently aligned the family visually with its protector, France (and in inverted colours: blue lilies on gold instead of the French golden lilies on blue). The Farnese coat of arms was also augmented: the papal keys were added in 1545 (a right for any Gonfalonier of the Church), and in 1586, Ottavio’s son Alessandro would add a quartering for Austria-Burgundy, for his mother’s family.

Every good Roman cardinal needs a country retreat, so Cardinal Alessandro Farnese rebuilt his grandfather’s villa in the Lazio, not far from his brother’s duchy of Castro. The Villa Farnese at Caprarola, with its famous pentagonal shape and circular courtyard, would become a model of the Roman country house and the showpiece for the family. One of the most famous rooms is the Sala dei Fasti Farnesiani (the ‘Room of Farnese Deeds’), which features a fresco commemorating Cardinal Alessandro’s efforts at bringing peace to Europe by coordinating a meeting between François I and Charles V in 1540. This palace too became part of the unified Italy after 1860, and was selected as the residence of the heir to the throne. Today the villa’s secondary building, the casino or summer house, is the country residence of the President of the Republic of Italy, while the main building houses a museum.

By the mid-1550s, Ottavio Farnese, 2nd Duke of Parma and Piacenza, settled in to rule his new states. Despite violent beginnings, the next thirty years of his reign was fairly unremarkable. He was moderate and popular. He focused his attentions on creating a ducal capital in Parma, and left Piacenza to his widowed mother, Girolama Orsini, who had been a key asset during the Parma War, using her Roman family connections to smooth relations with the papacy, and governing Castro as regent while her youngest son Orazio was in France. The other most important woman in his life, his wife Margaret, soon departed and became a separate actor in the history of the dynasty: in 1559 she was named Governor-General of the Low Countries by her half-brother, Philip II of Spain, and lived in Brussels for the next eight years, where she tried, unsuccessfully, to keep a lid on the boiling resentment against Spanish rule in the Netherlands. When Philip sent the Duke of Alba to put down the unrest and gave him full powers that undermined those of Margaret of Parma (as Margaret of Austria was now known), she resigned, and retired to her property of L’Aquila in the Abruzzo (part of the Kingdom of Naples).

Meanwhile, Ottavio set up his residence in Parma in the old Bishop’s Palace—an austere building dating from the 11th century—while he oversaw the development of finer buildings worthy of a ruling dynasty. First he built the Palazzo del Giardino, across the river (also called Parma) from the centre of the city. Starting in about 1560, it was constructed on the site of an old Sforza fortress and surrounded, as its name suggests, by gardens and parklands. The Palazzo del Giardino would be enlarged in the 17th century and again in the 18th century, and its gardens would be developed by Bourbon dukes along French formal lines.

Back across the river, closer to the old medieval core of the city, was a complex of buildings known as the Palazzo della Pilotta, which Ottavio developed in the 1580s, taking its name from the game of pelota, played by Spanish soldiers stationed there. The oldest building, on the river bank, was the Rocchetta, or keep, which was linked by a Corridore to some townhouses that served as the ducal court until a more grand palace was constructed in the next reign.

Duke Ottavio also patronised churches in Parma, notably the Shrine of Santa Maria della Steccata, named for the picket fence (steccata) which protected a miraculous image of the nursing Virgin from throngs of pilgrims. Here the Duke commissioned new interior frescos and constructed a crypt that would become the Farnese family sepulchre, and later that of the House of Bourbon-Parma (it remains so even today, with the most recent interment in 2010). I was annoyed last summer when I visited Parma and was unable to visit the crypt despite signage suggesting it was in fact open for tourists…

Ottavio and Margaret had only one son, Alessandro, a surviving twin whose brother had lived only a few months in 1545. After Spain agreed to recognise the independence of Parma and Piacenza in 1555, Philip II required the presence of young Alessandro in Spain as a sort of hostage. So while Margaret of Parma was sent to Brussels, Alessandro was sent to Madrid to be raised alongside Philip’s son, Prince Carlos, and Philip’s illegitimate half-brother, Don Juan (all about the same age). Alexander, Prince of Parma, grew to be one of the greatest commanders of the age, and would eventually be sent to the Low Countries to continue in the struggle to retain the loyalty of the rebellious Dutch provinces. In 1565, his semi-royal status was confirmed by his marriage to Maria de Guimarães, daughter of Infante Duarte of Portugal (the youngest son of King Manuel). He commanded three vessels in the important victory over the Turks at Lepanto in 1571, then in 1577 was sent to the Low Countries with an army to support Don Juan, who had been appointed Governor-General the year before. But Don Juan died just a year later, in October 1578, and so Alessandro Farnese replaced him as military commander, while his mother was recalled from her peaceful retirement to act again as Governor-General. The partnership of mother and son proved to be unworkable, however, and she retired once more in 1582, leaving Alessandro as Governor-General himself. He was successful in winning over the southern Catholic nobles who proclaimed their loyalty to Spain in 1579—thus creating in essence the modern nation of Belgium—and became known for his successful sieges, most notably at Antwerp in 1584-85. His greatest fame to English readers, however, came in the following years.

In 1586, Alessandro Farnese succeeded as 3rd Duke of Parma and Piacenza. He entrusted these duchies to his teen-aged son Ranuccio—legally old enough to rule, but in need of adult guidance since both his mother and now his grandmother were dead—while he remained to command Spanish forces in the Low Countries. Parma defeated the English troops sent by Queen Elizabeth I to aid the Dutch, and in 1487 secured the port of Sluis in Zealand—ready for an invasion of England once the grand Armada arrived from Spain. Of course, as is well known, the ‘Protestant Wind’ blew the Armada out of the Channel, so no landing was possible. Still hoping to secure victory in the Low Countries, Parma found himself pulled away as Philip II ordered him to France in late 1589 to aid the Catholic League in their defence of the true faith from the usurping claimant king, Henry of Navarre. With Parma’s aid, they did prevent Navarre from taking Paris, and again in Spring 1592 the same for Rouen, but by this point the great commander was getting sick and was pulled back and forth between France and the Netherlands, where the armies of Maurice of Nassau were growing in strength every day. Journeying once more to France in December 1592, he weakened in the border town of Arras and died.

The new duke of Parma and Piacenza (and don’t forget, duke of Castro as well), Ranuccio I, now 23, would have a long and mostly successful reign. As a teenager there was a brief glimpse of a much grander future, for him and for the Farnese dynasty, as he was put forward in 1579 as a successor to the childless uncle of his late mother (she died in 1577), Henry, the Cardinal-King of Portugal. But Philip II of Spain had a strong claim too, and given Parma’s quite strong connections to Spain at this time, when King Henry died in 1580, Ranuccio’s claims were not pressed (though later generations did add the arms of Portugal to the Farnese coat of arms, see above).

Instead, Ranuccio initiated a fresh wave of building in Parma. He decided to turn the townhouses linked to the Palazzo della Pilotta into a proper ducal palace, which was completed in about 1620. The jewel at its centre was the Teatro Farnese, built in 1618, totally out of wood, with capacity for over 4,000 spectators, and what is considered one of the first permanent proscenium arches in the history of theatre. The rest of the palace complex included a ducal stable, a gallery for the display of the family’s growing art collection, and the Church of Saint Peter. In the eighteenth century, this magnificent palace complex would be augmented further with the addition of the Biblioteca Palatina by the Bourbons. Much of the Pilotta was destroyed by bombs in World War II, but the Theatre and the Library miraculously survived, and the complex now houses two major museums, one of fine art and the other archaeology. He also revitalised the University of Parma.

Duke Ranuccio was also successful in curtailing the autonomy of some of the Duchy’s major feudal families, notably the Pallavicini and the Landi. From the Sanvitale family, he confiscated the estate at Colorno (in 1612), after a fairly brutal trial and public execution of its chatelaine, Barbara Sanseverino. The palace at Colorno, started by the Correggio family in the fourteenth century, became the chief summer residence of the Farnese dynasty, and would later be rebuilt by Duke Ranuccio II, employing one of the leading architects of the seventeenth century, Ferdinando Galli Bibiena.

Part of the impetus for this great ‘purge’ of 1612, was a reaction to a plot by which the Duke thought that several prominent nobles were conspiring against him, and in particular, encouraging his former mistress to practice witchcraft to ensure he had no male heir. In 1611, the spurned woman, Claudia Colla, was tried and burned at the stake. But it was true he had thus far no children from his wife, Margherita Aldobrandini, the niece of Pope Clement VIII, whom he married in 1600 (granted, she was only 11 when they married). In 1605, he took matters into his own hands and legitimated a son (from a different mistress), Ottavio (b. 1598), and began to raise him as if he were the heir to the duchies. But in 1610, Margherita did have a son, Alessandro, then another, Odoardo, in 1612. So Ottavio was removed from his father’s favour formally in 1618—he rebelled in 1621 and was imprisoned in the Rochetta for the rest of his life (two decades later). Duke Ranuccio hardly survived this rebellion and died in 1622.

His eldest son, Alessandro, was passed over as a deaf-mute, so the succession fell to ten-year-old Odoardo. He was at first guided as regent by his uncle, Odoardo, a cardinal since 1591. This latest Cardinal Farnese contributed to the family’s reputation for artistic refinement, by commissioning Carracci to paint frescos in his private camerino (study) at the Palazzo Farnese in Rome, and the famous Farnese Gallery ceiling, ‘the Loves of the Gods’ around the turn of the century.

Cardinal Odoardo died in 1626 and was replaced as regent by the young duke’s mother, Margherita Aldobrandini. For two years she ably kept these small states out of the growing conflict that would later be termed the Thirty Years War. When Odoardo came of age, however, he was brimming with enthusiasm for battle, and in 1633 directly challenged the might of the Spanish Habsburgs parked on his doorstep in Milan, by re-aligning his state with France. The neighbouring Italian prince, Francesco I d’Este, Duke of Modena, who only two years before had married Odoardo’s sister Maria Caterina, led a Spanish army to capture Piacenza and devastated the countryside. France, sadly, did not send help, and Odoardo was forced to sue for peace in 1637.

Duke Odoardo had spent heavily on raising troops, so pressed his already ravaged estates for more taxes. He also borrowed significant amounts from Roman bankers, and when these appealed to the pope (Urban VIII) for aid in getting re-payment, the Pope decided that this was a good opportunity to gain a duchy for his family, the Barberini, just as Paul III had done one hundred years before. He occupied the Duchy of Castro and declared the Farnese no longer vassals there. Odoardo and his ally the Grand Duke of Tuscany, Ferdinando II, whose sister he had married in 1628, were unable to defend these possessions in this ‘Castro War’, but by 1644 had made peace with the papacy, promising to pay the creditors. Castro was restored for now, but the Duke died soon after, in 1646, aged only 34. Once again a younger brother, another Cardinal Farnese (Francesco Maria), was called on to act as regent—but he too died young (at 27) in 1647.

In a repeat of the previous generation, Duchess Margherita de’ Medici now became regent for her son Ranuccio II, but only for a year, as he came of age in 1648, and immediately provoked a rematch with the Papacy over Castro. Not only did he refuse to pay the debts as his father had promised, he also refused to recognise the newly appointed Bishop of Castro—and worse, was probably involved in that prelate’s murder in 1649. Not a pope to be trifled with, Innocent X again revoked the fief of Castro, sent in his troops, and razed the city of Castro. It was never rebuilt, and its diocese was even transferred elsewhere. The main branch of the Farnese were now un-rooted from their ancestral homeland.

But there did remain another branch of the Farnese family in Lazio, the dukes of Latera—see above. Their castle, the Palazzo Farnese in Latera, located near the western shores of Lake Bolsena, was an ancient medieval castle, enlarged in the 15th century once it became a ducal residence. A new building was built next to it in 1550, in a more elegant Renaissance style—then they were joined together in 1625. Today the complex has been subdivided into various residences but still dominates this hilltop town.

I don’t know much about the earlier generations, from the founding of this branch in 1408, but they began making waves in the later decades of the 16th century. Mario I, 5th Duke of Latera (r. 1579-1619), was a soldier: he served under his distant cousin the Prince of Parma in the Low Countries, in the 1570s, then for the Emperor in Hungary; he was later instrumental in the Papal takeover of the Duchy of Ferrara from the Este family in 1598, and was named Captain-General of the Church in 1603. His older brother, Ferrante, was a churchman, and was appointed Bishop of Parma—an interesting dynastic cross-pollination—in 1573. The dynastic relationship was not enough however, and he clashed continually with the dukes and the local nobility in trying to extend greater Church authority over the city. The situation became so tense that the Pope intervened and sent Bishop Farnese away on long missions, first as Papal Legate to Bologna in 1591, then as Apostolic Nuncio to the Imperial court in Prague in 1597. Another notable member of the clergy at this point was Mario’s daughter, Isabella, who entered the Order of Poor Clares and took the name ‘Suor Francesca’. Her father built a new monastery for the Poor Clares in the village of Farnese (Santa Maria delle Grazie) in 1618, and she became its first abbess. She later founded monasteries all over Lazio and in the city of Rome itself, and when she died in 1651, was declared to be ‘venerable’ (a step below sainthood).

Duke Mario had numerous sons, who succeeded as Duke of Latera in succession. The last of these was Girolamo, who was also a cleric when he became the last duke in 1662. He had been Apostolic Nuncio to the Swiss Cantons in 1639, then Governor of Rome in 1650 and Prefect of the Apostolic Palace and Governor of Castel Gandolfo (the papal country retreat) in 1655. Finally elevated to the cardinalate in 1657, he then succeeded as Duke of Latera and governed for six years before he died in 1668. With no heirs, the fief returned to the Papacy. There were now no Farnesi in Lazio at all.

Back in Parma, Ranuccio II had now settled in, after the 2nd Castro War, to a relatively long reign, from 1646 to 1694, which marked a new cultural high point for the Duchy—he patronised artists and musicians and brought to Parma many of the great treasures from the family’s residences in Rome. He tried to re-purchase the Duchy of Castro, and the Papacy extended the terms several times; but finally he gave up (by 1666), and focused more fully on Parma and Piacenza—he was a good ruler, re-developing the local economy after the Thirty Years War, and improving agriculture by draining wetlands near the Po. With the money he saved, Ranuccio purchased two more imperial fiefs—those of the Landi family, at Bardi and Compiano—to add to the duchy in 1682. He married three times, maintaining dynastic ties with his neighbours in Turin and Modena.

Duek Ranuccio II’s foreign policy was also balanced: his first younger brother, Alessandro, was destined for the Church (every Farnese generation needs a cardinal!), and the second, Orazio, was given a commission to lead Farnese troops in the service of Venice against the Ottomans. When Orazio died of a sickness on his journey home in 1656, Alessandro took his place, then was sent to Spain to try to revive the glorious career of their great-grandfather of the same name. The King of Spain repeatedly appointed him to high commands, as a general in the war against Portugal in 1664, then as Viceroy of Catalonia in 1676 to defend that province against French invasion, but in both cases he was soon withdrawn, having offended many of his officers and those back at court in Madrid by his extravagant and pompous lifestyle and his relationship with the prostitute Maria de Laó y Carillo, who lived with him as a wife for many years. Yet due to close dynastic connections he had with the Spanish king, and the many persuasive letters of his brother Ranuccio back in Parma, Alessandro finally achieved the family goal and was named Governor-General of the Netherlands in 1680. Here too his insistence on being treated as a royal highness and his lavish spending made him an embarrassment for the Spanish court, and he was once again dismissed, in 1682—much to his relief as armies of creditors closed in on his residence in Brussels. He returned to Madrid in 1687 where he was appointed a Gentleman of the Chamber, Councillor of State, Admiral of the Spanish Navy and Knight of the Golden Fleece…but he died just over a year later, leaving his massive debts to be paid by his brother and his illegitimate son Alessandro.

Meanwhile, Ranuccio II feared the ongoing conflicts between Austria, France and Spain, which usually used the plains of northern Italy as their battleground, so he continued to solidify his links with the Habsburgs by arranging a marriage of his son Odoardo to Dorothea Sophia of the Palatinate, in 1690. She was incredibly well connected: as younger sister of the Holy Roman Empress, the Queen of Portugal, and the new Queen of Spain. A new heir for the dynasty, Prince Alessandro, was born in December 1691, but lived only until August 1693, and was soon followed to the grave by his father, the Hereditary Prince Odoardo, in September, and then by Duke Ranuccio II himself a year later in 1694. Only one daughter remained, Elisabetta, born in October 1692, who would later become one of the most famous women of the early eighteenth century as Isabel, Queen of Spain.

When Ranuccio II died in 1694, his state was nearly bankrupt, so his second son, Francesco, took extreme measures as new Duke of Parma and Piacenza. He dismissed huge numbers of servants, musicians, jesters and dwarves, and stopped the practice of regular court spectacles and lavish banquets so enjoyed by his father. He also married his brother’s widow, Dorothea Sophia, so he wouldn’t have to return her sizeable dowry. She was of a much more sober (maybe we can say ‘Germanic’) temperament, so she worked closely with her husband to restore the Duchy’s finances. Together they did sponsor the arts, however, and in particular stressed learning, improving the University of Parma and founding a College of the Nobility which encouraged Parmesan noble sons to become useful servants of the state by studying law, languages or mathematics. When the War of the Spanish Succession broke out in 1702, Duke Francesco managed to keep his states neutral, though they were occupied by Austrian troops led by Prince Eugene of Savoy, and towards the end of the war he was forced to recognise that his duchies were now fiefs of the Empire, no longer vassals of the Papacy. Seeing that neither he nor his brother Antonio had sons, both Vienna and Rome hoped to incorporate Parma and Piacenza into their domains. But in 1714, Francesco and Dorothea Sophia played their one remaining trump card—in an effort to stave off absorption into the Austrian domains—and married off Princess Elisabetta to King Philip V of Spain, a Bourbon and thus a rival of Austria. She changed her name to the more Spanish Isabel and soon became a crucial part of Philip’s reign, as a strong-willed princess able to counteract his increasing depression and mental instability.

In 1718, the Treaty of London was signed between Austria, Spain, Britain, France and the Dutch, who all recognised that Isabel Farnese was the heiress of Parma and Piacenza (and in fact of Tuscany too, via her Medici great-grandmother), with the assumption that these territories would be given to her eldest Bourbon son, the Infante Carlos of Spain.

In February 1727, Duke Francesco died and was succeeded by his brother Antonio, a prince of a very different character. Forbidden from living a life of parties and luxury by his austere brother and sister-in-law, he had lived for years at his country house, the Rocca di Sala, another of those country seats taken from the feudal nobility by Duke Ranuccio I back in 1612. The Sanvitale family had held the fief of Sala, a few miles southwest of Parma, since the mid-thirteenth century, and had built the Rocca as their residence in the fifteenth century (when their fief was elevated by the Duke of Milan into a county). In the seventeenth century it served as one of many hunting lodges for the Farnese family, and in 1723, Antonio decided to make it his seat, which he enlarged and renovated. As duke, he continued to reside there, reviving the more extravagant court of his father, with gambling and feasting late into the night, living openly with is mistress Countess Margherita Bori Giusti.

Duke Antonio’s first minister convinced him to marry, which he did in July 1727, to a local Este princess, Enrichetta, daughter of the Duke of Modena. But his health was terrible—morbidly obese, like his cousin Gian Gastone, the last Grand Duke of Tuscany—and there was little chance of a child. Yet his niece Queen Isabel, concerned for her son’s agreed inheritance, arranged with France and Spain in 1729 to permit the stationing of 6,000 Spanish troops in Parma to safeguard it from Austrian ambitions. Duke Antonio renounced the Emperor’s recent claims to suzerainty, which prompted an amassing of Imperial troops on the frontiers with Milan. When Antonio suddenly died in January 1731, Austrian troops swiftly moved in and convinced Duchess Enrichetta that she was pregnant, to forestall the claiming of the Duchy by the Infante Carlos of Spain. She reigned in Parma in the name of her unborn child, while the indomitable Dowager Duchess Dorothea Sophia pressed for her to be examined to determine if she was really pregnant. In September the fallacy was revealed, so Austria, humiliated, agreed to allow Carlos to move in—though he had to formally recognise his status as an Imperial vassal. The Dorothea Sophia was named regent, and Enrichetta was kept under house arrest until she, under force, returned the ducal crown jewels. Nine years later she remarried, a German prince from Hesse-Darmstadt, and she moved away.

The House of Farnese passed into history. Isabel Farnese, Queen of Spain, lived for many more years, surviving her husband Philip V by twenty years, and dying in retirement at the Palace of Aranjuez in 1766. Her son Carlos—now Carlo in Italian—became much more than just duke of Parma and Piacenza. Only a few years after taking up the reins in his Italian duchies, he marched south and easily ousted the Austrians from the kingdoms of Naples and Sicily and declared himself king. His younger brother, Infante Felipe, would later be installed as duke of Parma (1748), while he himself succeeded his older half-brothers as King of Spain, as Carlos III, in 1759. His descendants would continue Isabel Farnese’s line in Spain, but also established a separate line in Naples; his brother’s descendants continued to rule in Parma and Piacenza until they were overthrown during the Risorgimento in 1859. The Bourbon-Parma line continues to this day, as rulers of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg (since 1964, though formally known as the House of Nassau-Weilburg), but also as extended members of the Dutch royal family (due to the marriage of Carlos Hugo, Duke of Parma, to Princess Irene of the Netherlands in 1964), and as Carlist pretenders to the Spanish throne. The Farnese family achieved what no other papal family had—not the Borgias, not the Barberinis—in securing an independent principality carved out of papal lands that endured for nearly 200 years.

(images from Wikimedia Commons)

i love your blog its good . please think about visiting mine

I will follow and give a like! My Blog is about Lake Garda in Italy Check it here http://www.lakegardatourist.com

LikeLike

now I really want to visit!

LikeLike

very fascinating. congratulations. who will write a modern life of Elizabeth Farnese?

interesting that the Imperial claim to suzerainty never goes away.

nor did the Farnese claim to Tuscany, Napoleon makes the Duke of Parma king of Etruria in 1801.

LikeLike

there are new biographies of her, but they are in Spanish and Italian.

LikeLike

Have you ever read an interesting non-religious justification of dynastic rule? Why be ruled by one family, instead of something like Switzerland or Venice?

LikeLike

I think Machiavelli writes about it as not being ideal, but an efficient way to avoid chaos and disorder

LikeLike

Just read your article on the Farnese. Thanks for an excellent work!

Have you come across any material connecting the Farnese with the Mancini family of Canino?

LikeLike

Thanks Steve. I really enjoyed researching that one. Since Canino was in the heart of their original territories, and they had many many branches in the Middle Ages, I wouldn’t be surprised if there was some connection to a Mancini family from the region. I do know that the Roman family of Mancini had some estates in the same region, but my knowledge of Mancinis is really only once they become a ‘French’ family as Dukes of Nevers in the 17th century. Jonathan

LikeLike

Found my way here searching for a St Farnese who was favored to have held the baby Jesus…maybe your Suor Francesca? If true, how blessed she was!

LikeLike