In the middle of the Atlantic lies a small green island, known as Terceira, as the ‘third’ island to be discovered in the Azores archipelago by Portuguese navigators in the mid-15th century. At over a thousand miles off the coast of the mainland, Terceira would not normally be thought of as a likely seat for a dukedom. And it wasn’t, really, but it did give its name to one, created in 1832, for one of the defenders of liberal government in Portugal, Antonio José de Sousa Manoel de Menezes Saverim de Noronha, 7th Count of Vila Flor. He was given this title in honour of the attack he launched from the island of Terceira earlier that year to defend the rights of the Queen Maria II against her usurping uncle, and a proponent of royal absolutism, Dom Miguel, Duke of Beja. The Duke of Terceira would remain a prominent figure in Portuguese politics for the next two decades, with several terms as Prime Minister.

Picking one name out of the extremely complex surname of the Duke of Terceira, ‘Manoel’ links this Portuguese nobleman to a much more extensive dynastic network, with branches in both Portugal and Spain. All of them claimed descent in one way or another from a royal prince, the Infante Manuel, who lived in the middle of the 13th century. By the early 19th century, the Duke of Terceira was the head of the Portuguese branch of the House of Manuel (spelled Manoel in Portuguese, though not always); while the Count of Via Manuel was head of the family in Spain. Ultimately, the Spanish branch would also receive a dukedom, Arévalo del Rey, but not until 1903. A third dukedom appears briefly in this family’s story, that of Tancos, also in Portugal, which only lasts from 1790 to 1791. Reaching much further back to the earliest history of the Manuel dynasty, however, we see one of the most prominent and autonomous (though never officially proclaimed) of all Iberian dukedoms, that of Villena, and this name would remain attached to the dynasty, as Villena, or Vilhena in Portuguese, for the rest of its history.

In 1252, the Infante Manuel, the 7th son of King Ferdinand III of Castile and Leon, was given the lordship of Villena as his apanage. It was a strategic territory, recently conquered by the King of Aragon from the Moors, but then taken from Aragon by the King of Castile. The lordship straddled the boundary between Castile and Aragon, and thus gave its lord both autonomy and also a useful position as a negotiator between the two often feuding Christian kingdoms. To secure his power in the region further, he was named Adelantado of the Kingdom of Murcia—the adelantados were powerful governors of newly conquered provinces, with nearly autonomous military and judiciary authority. Closer to the court of his brother King Alfonso X, Don Manuel was given the strategic castles of Peñafiel and Escalona, and served his brother as Alférez, or head of the household guard, then promoted to his Mayordomo mayor in 1279. He had his own household equal in stature to most princes—which seems appropriate for his very ‘imperial’ Greek name, ‘Emmanuel’, reflecting his maternal grandmother’s origins as a Byzantine princess (Irene Angelos, the daughter of Emperor Isaac II). He also married as a prince, first to a princess from Aragon (Constance) and then a princess from Savoy (Beatrice). His sons from both marriages took the name Manuel as a sort of surname, as would their descendants for the next 800 years. The eldest, Alfonso Manuel, died at 16, so the younger son, Juan Manuel, inherited the family properties, and assumed the title ‘Prince of Villena’. Though Villena was never formally more than a lordship, Juan was recognised as a prince in 1330 by the King of Aragon, and as a duke in 1336 by the King of Castile.

The castle at Villena was incredibly strategic, at the intersection of Castile, Aragon and the Muslim states to the south. A much earlier wooden fortress was replaced with a stone tower sometime in the 1170s, and remained the stronghold of the Manuels until the 1360s, then was given by the Crown of Castile to various younger princes and royal favourites (and was erected as a marquisate in 1366, then finally a dukedom in 1418), until it was integrated fully into the royal domain by the end of the 15th century (the title ‘Marques de Villena’ was given out again, but not the castle). Despite losing its value as a border post by the 16th century, Villena remained a royal military stronghold until the days of the Peninsular War at the start of the 19th century.

The other major fortress of the Manuels, Peñafiel, had been a strategic castle long before the era of the Infante Manuel, with foundations built by the earliest counts of Castile as they expanded their reach southwards from their capital of Burgos in the 940s. Its name means ‘loyal rock’, from the Latin pinna fidelis, and this great fortress on a rock grew and grew, until it was one of the most recognisable of Old Castile’s famous castles. Prince Juan Manuel called himself ‘Duke of Peñafiel’ by the 1290s, but, as with Villena, there’s no documentation for such a creation. It was, however, created a dukedom more formally later for the Infante Ferdinand of Antequera, who later became King Ferdinand I of Aragon.

A bit further south, the castle at Escalona was located on the road between Toledo and Avila, southwest of Madrid, also on the (at that time) strategic southern frontier of Castile. It had been a Roman fortress, then a Muslim stronghold, and was particularly strategic in the expanding frontier of the 12th century. The mighty castle we see today is the result of the expansion into a palace by the royal favourite Alvaro de Luna in the 1420s-30.

Juan Manuel, Prince of Villena, was born at Escalona. And although like his father he served at court, as Mayordomo mayor for his cousins Ferdinand IV and Alfonso XI, he is best remembered as a writer (and bears the nickname ‘el Scritor’). He wrote numerous books, mostly guides for how to live and govern as a prince, but also how to write poetry or how to use weapons properly. Also like his father, he served as a useful diplomat between Castile and Aragon, until he began a long a bloody feud against Alfonso XI in the 1330s. He died in 1348, leaving his lands and titles to his son Fernando Manuel, who died only two years later, succeeded by an infant daughter, Beatrice, who some sources consider to be the 3rd Duchess of Villena (or of Peñafiel). But she too died, in 1361, aged 13 or 14. All of the estates of the House of Manuel—Villena, Peñafiel and Escalona—were inherited by Fernando’s sister, Juana, who had married the Infante Enrique of Castile, soon to become King Enrique II. As noted above, Villena passed therefore to different hands, as did Peñafiel. Escalona was given to Juan Pacheco and created as a dukedom in 1472 (along with a marquisate of Villena). The House of Pacheco would remain one of the most powerful ducal families of Spain until the end of the 18th century.

This was not the end of the House of Manuel! Juan Manuel de Villena had an illegitimate half-brother, Sancho, who was created Lord of Carrión, in Castile near the city of Palencia. This lordship was raised to the rank of a county for his son Juan Sanchez Manuel in 1371. Both Sancho and Juan served their manueline cousins in the administration if their lands in Murcia and in their armies further south. Alfonso, 2nd Count of Carrión, died in about 1393, and his lands passed through his sister to the Padilla family. Meanwhile, another branch was forming across the border in Portugal. Juan Manuel had another illegitimate son, Enrique Manuel de Villena, who accompanied his half-sister, Constanza, to her marriage in 1340 to the Infante Pedro of Portugal. Enrique was only a child, and Constanza’s marriage did not last long (she died in 1349), but Enrique stayed in Portugal, and after Pedro became King of Portugal in 1357, he secured the young man’s loyalty with the title Count of Seia (in north-central Portugal), the lordship of Cascais and the office of alcaide (mayor) in Sintra, both much closer to the capital of Lisbon, plus many other castles in the Kingdom. The new Count of Seia was also married to a daughter of a prominent Portuguese noble house, Sousa (which we will encounter again below). But after King Pedro’s son King Ferdinando’s death in 1383, Henrique Manoel de Vilhena (adopting the Portuguese spelling) was one of the first to proclaim the late king’s daughter, Infanta Beatriz, as Queen of Portugal, meaning that her husband, King Juan I of Castile, could claim the Portuguese throne against João of Aviz. This support for Juan meant, however, that after this dynastic struggle which ended in the victory of the House of Aviz, Henrique was sent packing back to Castile, and his Portuguese lands were lost. Juan I compensated him, however, with the lordships of Montealegre, Belmonte and Meneses, located near the city of Palencia in western Castile. By the end of his life, Enrique was an advisor to the Infante Ferdinand of Castile in his regency (from 1406) and later as he established himself as king of Aragon (from 1412), and Mayordomo of his wife, Queen Leonor de Albuquerque (see her family, for another fascinating cross-Portuguese-Spanish ducal family).

Enrique Manuel de Villena started a new line through his two sons, Pedro and Enrique II, successively lords of Montealegre, Belmonte and Meneses. Pedro was the first to be buried in the Dominican convent of San Pablo in Peñafiel—retaining his family’s older link with that fortified town—where the ‘Capilla de los Manueles’ remained the family pantheon for generations. Enrique II’s son, Enrique III, was created Count of Montealegre by the King of Castile in 1406. The genealogies I’ve looked at become quite muddied at this point, and if Enrique I is still alive in 1412, then it doesn’t make sense (to me) for his grandson Enrique III to be created count in 1406—other sources show this as just one generation, not three. In any case, an important split occurred in the early years of the 15th century, and one branch remained in Castile as lords of Belmonte (Belmonte de Campos) and another moved further west as lords of Cheles, on the frontier near Badajoz, and then hopped across the border back to Portugal. We will look at the Castilian lines first.

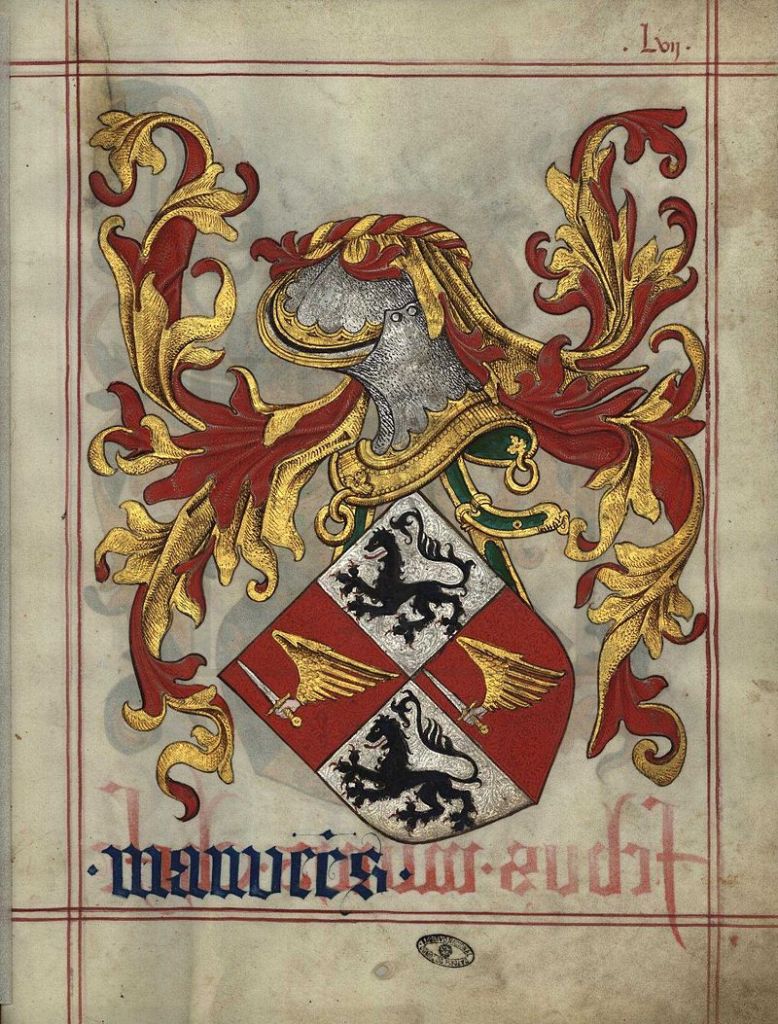

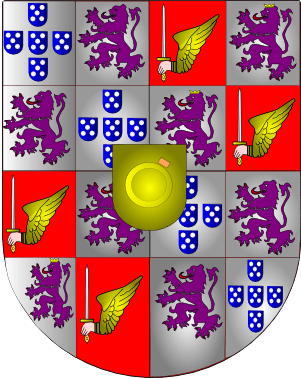

But first, there is another side line descended from the first House of Manuel to explore. In truth, they may not be related at all—another one of history’s grand genealogical fictions. João Manoel, Bishop of Ceuta and Primate of Africa (from 1443) then Bishop of Guarda, in eastern Portugal (from 1459), was for many years considered by royal historians and noble genealogists to be the son of King Duarte of Portugal (d. 1438) and his mistress, Joana Manoel de Vilhena (a grand-daughter of the Count of Seia), an idea that has now been fairly conclusively dismissed. Manoel in this case may simply have been the Bishop’s second name which became a patronymic for his illegitimate offspring. Nonetheless, these descendants formed another House of Manuel in Portugal—and tellingly, they assumed the very same coat of arms.

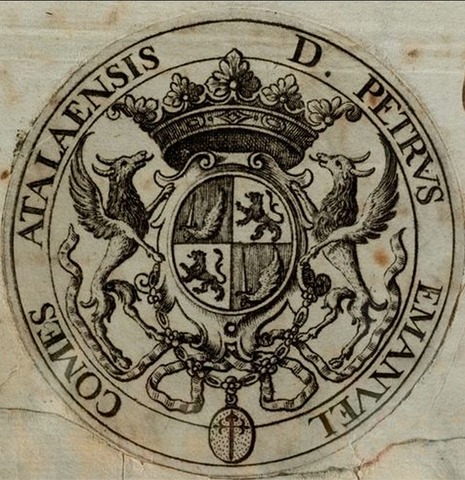

At first they were lords of Salvaterra de Magos in the fertile central belt of the river Tejo (or Tagus), northeast of Lisbon, then by the 16th century they were also lords of Tancos, further upriver, and nearby Atalaia. Two marriages to heiresses in that century merged them with the powerful family of Ataide, and in 1583, they were created Count of Atalaia by King Philip II of Spain—since 1580, the new King Philip I of Portugal. The family did well under Habsburg rule in Portugal: the first count, Francisco Manuel de Ataide, was succeeded in 1624 by his brother Pedro, previously a soldier in India in the 1590s and Viceroy of the Algarve in 1621. Their other brother, João, was Bishop of Viseu from 1609, then of Coimbra in 1625, before rising to the top of the ecclesiastical hierarchy as Archbishop of Lisbon in 1632. He was even named Viceroy of Portugal by Philip IV of Spain (Philip III of Portugal) in March 1633, but died only a few months later.

Jumping ahead, the 5th and 6th counts of Atalaia, brothers Pedro and João Manoel de Ataide, were both successful Portuguese commanders in the War of Spanish Succession, supporting the cause of Archduke Charles of Austria against the forces of the Bourbons. Pedro continued to support Charles after the war, now Emperor Charles VI, as Viceroy of Sardinia, 1713-17, and general of cavalry in Austrian-ruled Naples. João became Governor of Portuguese Angola (also 1713-17), then returned to Lisbon to become governor of the Tower of Belem guarding the river Tejo at the gateway to the capital. He succeeded his brother as 6th Count of Atalaia and later in life joined the royal Council of State and served as Master of the Household for Queen Mariana Vitoria in the 1750s. He was promoted in 1751 to the rank of Marquês of Tancos, and died in 1761, the last male of this line. His daughter, Constança became 2nd Marquesa of Tancos, and as a widow was appointed Camareira-mor (First Lady in Waiting) to Queen Maria I, who honoured her with the lifetime title, Duchess of Tancos, in 1790. She died a year later and passed her other titles (the county of Atalaia and the marquisate of Tancos) to her daughter and her heirs in the House of Meneses, though they took the name and arms of Manuel. They lived in the Palácio de Tancos in Lisbon, a lovely pink building high up on the hillside of the Castle of São Jorge.

Of the branch of the Manuels that remained in Castile, the lords of Belmonte, Juan III rose to greater heights as one of the chief fiscal officers of Castile (the Contador mayor) and as ambassador to Henry VII of England and later to Pope Leo X. In the 1520s Belmonte was a councillor of state for King Carlos I (Emperor Charles V), and restored his family chapel in Peñafiel, where he is buried.

His son Lorenzo Manuel was Mayordomo mayor to Charles V, but was the last of his line, passing the estates of Belmonte and others near Palencia to his sister Aldoza. His cousin in a junior line, another Juan Manuel, Lord of Cheles, also served as a mayordomo in the household of the Emperor-King. This Juan had two sons: the elder, Francisco I, continued to guard the frontier of Extremadura from his castle at Cheles and was progenitor of the line of counts of Via Manuel; while the younger, Cristobal, became lord of Carapinha across the border in Portugal, and founder of the line of counts of Vila Flor. From the first came the Spanish dukes of Arévalo, and from the second the Portuguese dukes of Terceira.

Cristóbal Manuel de Villena, 1st Count of Via-Manuel (or Villamanuel in the early days), was general of artillery in the wars against Portugal in the mid-17th century and governor of Badajoz near the border. His nearby castle at Cheles guarded the Guadiana river as it crossed this frontier, so he was ideally placed for this post, and alongside his countship, created by Carlos II in 1689, he was created Viscount of the Villa de Cheles. This castle is today called the Palacio Señorial of the Counts of Via Manuel.

A series of counts named José followed in the 18th century, the last of which made an advantageous marriage in 1790 to Maria del Pilar Melo de Portugal, from one of the most prominent noble houses in Portugal, though by this point they were also large landowners in Spain. She was, for instance, the 10th Marquesa de Rafal, based in the Kingdom of Valencia near Alicante, and 7th Countess of Granja de Rocamora, located in the same area (the Rocamora family had been one of the leading noble houses of this region in the Middle Ages). Her son Cristóbal, 6th Count of Via Manuel, was killed by Carlists in 1834, leaving a grandson, José Casimiro, to inherit both lineages’ titles and estates, as 7th Count of Via Manuel and 11th Marques of Rafal. He too was murdered, in 1854, leaving a very young son, Enrique, who died in 1874, aged only 21.

This branch of the Manuel family thus came to an end in the male line, but, as with so many Iberian dynasties, the name was simply transferred through the female line along with the estates. Doña Maria Isabel Manuel de Villena married Arturo de Pardo, a deputy to the Cortes and later senator of the realm, and a Gentleman of the Chamber of King Alfonso XIII. At the time of their marriage in 1867, she was created 1st Marquesa de Puebla de Rocamora, and she planned to separate the two estates (Via Manuel and Rafal) once more for her sons, Arturo and Alfonso. But she lived to the ripe old age of 80 and outlived the elder son (below). Several of her daughters inherited her longevity genes: Maria de Milagro lived until 101, while Josefa lived until 106! Second son Alfonso did inherit the marquisate of Rafal, which his descendants continue to hold today.

Some of the lovely estates of the Rocamora branch of the family in Valencia include the palace of the marqueses of Rafal and the palace of the counts of Granja, both in the small city of Orihuela in the Province of Alicante.

The elder son of Doña Maria Isabel, Arturo de Pardo y Manuel de Villena (1870-1907), was given his mother’s barony of El Monte Villena in advance of his succession while she lived, but obtained a much higher title due to his close friendship with the young king, Alfonso XIII; they shared a passion for horses, and Arturo became Master of the Royal Maestranza de Caballeria (a noble equestrian club) of Zaragoza. His mother pushed for years to have him recognised as the head of the ancient House of Manuel in Spain by means of the revival of an ancient dukedom from the 15th century, Arévalo, based on a castle and estates north of Avila, which she claimed had belonged to the medieval manueline lords. This had been continually blocked by the House of Zuñiga, whose ancestors had genuinely held the old dukedom of that name, but the King was persuaded to grant it anyway, in 1903, with the addition of ‘del Rey’ to make it distinct.

The first Duke of Arévalo del Rey died before his mother, so his son, Carlos Pardo-Manuel de Villena, inherited his grandmother’s title as 10th Count of Via Manuel, as well as his father’s title as 2nd Duke of Arévalo. He was a Gentleman Grandee of the Chamber of Alfonso XIII and supported him in exile after his deposition in 1931. His eldest son took the title 11th Count of Via Manuel in 1945, but not the ducal title, which went to his younger brother, Arturo. When he died childless in 2005, the ducal title passed to their sister, Maria Consuelo, who ceded it a year later to her son Juan Pablo de Lojendio y Pardo-Manuel de Villena (b. 1950), who is thus today the 5th Duke of Arévalo del Rey. The surname Lojendio comes from his father, a respected diplomat representing Spain in Switzerland, Italy and later the Vatican, but most famously in Cuba where his daring to argue on television with the new dictator Fidel Castro in 1960 caused an international incident—he was given 24 hours to leave the country.

Finally, the line of Counts of Vila Flor, which leads us back to Portugal and back to Terceira. Sancho Manoel de Vilhena was a prominent military commander in the struggle against the Dutch in Brazil, 1638-40, then a general in the War of Restoration in Portugal though which the Braganza dynasty re-established Portuguese independence from Habsburg Spain. In gratitude, the Queen Regent, Luísa de Guzmão, named him 1st Count of Vila Flor, a village on the eastern edge of Portugal, in 1659. He married the heiress Ana de Noronha, daughter of Gaspar de Faria Severim, a Secretary of State, thus adding these surnames to his inheritance, as we will see again below. The 1st Count was also Alcaide-Mor (military governor) of Alegrete, an important defensive town close to Vila Flor, as well as a councillor of state, governor of the Tower of Belem, and so on. In 1677, he was named Viceroy of Brazil, but died before he took office.

Sancho’s eldest son Cristovão succeeded him as 2nd Count of Vila Flor and Alcaide of Alegrete, while his younger son Antonio became much more famous as a naval commander in the Order of Malta (aka St. John of Jerusalem). In 1722, he was elected Grand Master of the Order, and he really left his mark on the small island of Malta in his 14 years of rule. For himself he built the Palazzo Vilhena in the old capital of Mdina in 1726 (today’s National Museum of Natural History), while for the Order he built a new fort to defend the port of Valetta (Fort Manoel), and new settlement nearby called Borgo Vilhena, now called Floriana (after his family’s title, Vila Flor). Still today the Manoel coat of arms can be seen all over Malta.

The 2nd Count of Vila Flor died without a legitimate male heir in 1704, so the title, and the name Manoel de Vilhena, passed to his sister’s son, Martim de Sousa Meneses. Along more orthodox lines of genealogical reckoning, this means that the House of Manoel died out in this branch, and the title passed to the House of Sousa. But this being the Iberian peninsula, anything goes, and the 3rd Count simply added the name Manoel to his other patronymics. Sousa is one of the very oldest, and most widely spread, noble names in Portugal, and as direct descendants in the male line (though illegitimate) from King Alfonso III (d. 1279), are considered by genealogy nerds to be one of the most junior branches of the House of Capet—the family that includes the Bourbons, the Valois, and the first royal house of Portugal, the Casa de Borgonha (Burgundy). The House of Sousa is fascinating in its own right, and will have a blog post of its own, focusing on the Duke of Palmela (another 19th-century Portuguese dukedom). A different branch of the Sousa family, hereditary grand butlers (copeiro mor) of Portugal in the 16th century, ultimately produced Martim de Sousa Meneses, and his son, Luis Manuel de Sousa e Meneses, 4th Count of Vila Flor. Martim also had a daughter, Mariana, who, like the Duchess of Tancos above was also Camareira-Mor of Queen Maria I, and was created 1st Marquesa de Vila Flor in the 1770s.

The 5th and 6th counts of Vila Flor were both involved in colonial government of Brazil, the first as governor of Pernambuco, the second as governor of Maranhão. The 6th Count, Antonio de Sousa Manoel de Meneses Severim de Noronha, died in 1795, leaving his three-year-old son, Antonio José as 7th Count of Vila Flor. This returns us to the Duke of Terceira.

Born in 1792, young Antonio learned his craft as a young officer in the Portuguese armies in the Napoleonic Wars of the early 19th century, rising to the rank of colonel by 1815. Two years later he sailed to Brazil to join the royal Braganza court in exile there. He helped put down a rebellion in Pernambuco and was named governor of the province of Grão Pará (the Amazon basin). In 1821, King João VI decided finally to return to Portugal, and the Count of Vila Flor accompanied him, as one of his Gentlemen of the Chamber. Portugal was in the midst of a long struggle between the forces of constitutional liberalism and royal absolutism, the latter led by the King’s younger son, Dom Miguel. At first, Vila Flor supported this absolutist party and served as field marshal and aide-de-camp to Miguel. As further evidence of this early stance, wee see that he was sent to Spain in 1823 to greet the Duke of Angoulême, the nephew of the King of France who had been sent to Iberia with an army to restore absolute rule in both Spain and Portugal. But by 1824, Vila Flor was shifting in his political mind-set towards liberalism, especially after the murder of his father-in-law by the Miguelists. When the King died in 1826, his son Pedro IV—who had proclaimed himself emperor of an independent Brazil in 1822—issued a formal constitution, then abdicated in favour of his seven-year-old daughter, Maria. Civil war followed, now with Vila Flor supporting the regency of the young queen against the forces of her uncle Miguel. He was rewarded with the title Marquis of Vila Flor in 1827.

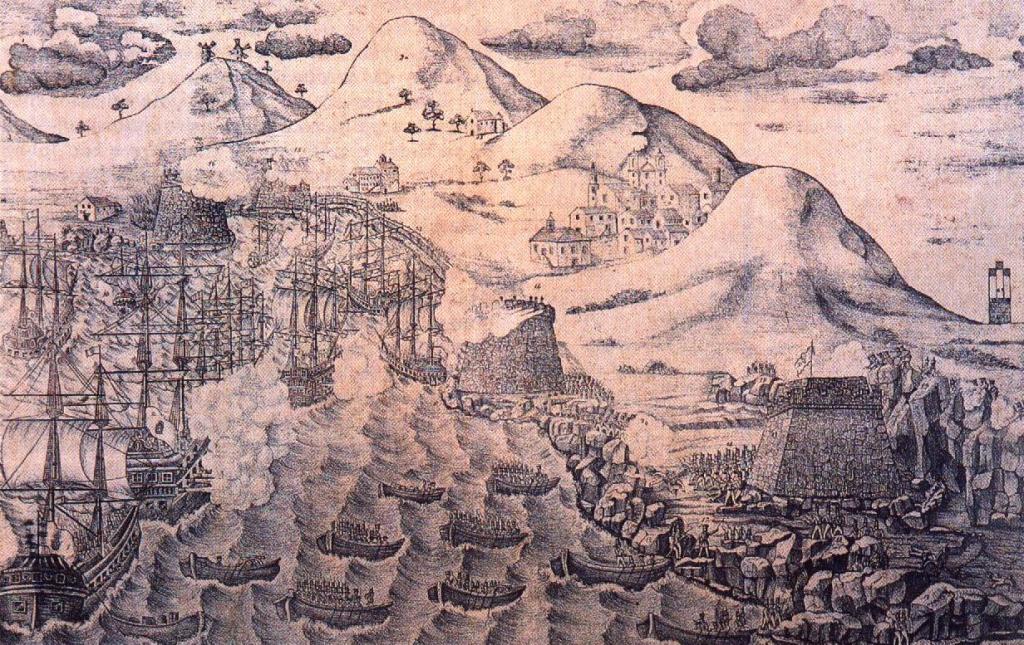

Dom Miguel took power in Portugal in 1828, forcing Vila Flor to join liberal exiles gathering in London (where the Queen lived). He soon joined two other leaders of this movement on the Island of Terceira in the Azores where they formed a regency government of their own, recognised by Queen Maria and her father Emperor Pedro, acting as regent from Brazil. Vila Flor was named Captain-General of the Azores, and gradually extended the government of the regency over the entire archipelago, fighting off a Miguelist fleet in the Battle of Praia in August 1829.

Their headquarters was in the ancient port town of Angra, on Terceira—since the mid-15th century one of the key stopping points for Portuguese ships crossing the Atlantic on the return voyage from Brazil, laden with colonial bounty (and thus this port was heavily fortified). In March 1832, Dom Pedro arrived in Angra to take up the regency for his daughter himself, and from there, he and Vila Flor launched the invasion of the Portuguese mainland that summer, starting in Porto. Pedro took formal command of the army in November, and as a thank-you created the dukedom of Terceira for Vila Flor. The new Duke was sent to take over the Algarve, then in July 1833 took the city of Lisbon from the Miguelists. He defeated the remaining rebel army at Asseiceirain May 1834, and the civil war (the ‘war of the two brothers’, Pedro and Miguel) ended.

In September 1834, Queen Maria II formally took over the government for herself, and appointed the Duke of Terceira as her Minister of War. In the next decade he became leader of the more moderate wing of the Liberal party, and in April 1836, was asked to form a government when the more leftist group fell from power. This would be his first stint as President of the Council of Ministers (aka Prime Minister), but his government was seen as too heavy handed, and after an uprising in September, was dismissed, replaced once more by the more left-wing liberals. In the summer of 1837, Terceira joined an uprising against these liberals with some of his former military companions, the ‘Revolt of the Marshals’, and they formed a provisional regency government of their own, aiming to restore the original constitution of 1826. This failed and they were exiled—but he was almost immediately recalled when war threatened with Spain over border disputes. In 1842, the old constitution was restored, and Terceira was once again asked by the Queen to be Prime Minister (and again, Minister of War), which he did, for four years, one of the few periods of stability in this monarch’s troubled reign. After his resignation in 1846, he worked as a now senior politician in the Chamber of Peers (the upper house of Parliament), until he was asked to form yet another government after a short civil war in 1851. This was evidently a transitional government and indeed lasted only 6 days.

By the mid-1850s, the Duke of Terceira had left active military service, but continued to be a strong presence in Parliament, still as a liberal, but now more as a patriarch of the Kingdom, one of the few unifying figures who could stand above politics. Maria II died in 1853, and Terceira acted as a father-figure to her son, the teen-aged King Pedro V. As a trusted senior statesman, he was sent to Germany to receive the King’s bride, Stephanie of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen, in 1858. And in March 1859 he was once again called on to form a government (and appointed Minister of War and Foreign Affairs)—he died in office a year later.

The Duke of Terceira lived at the (Old) Palace of Vila Flor, in Alfama, the fashionable district of Lisbon on the far side of the old Castle of São Jorge, along the banks of the River Tagus, also called the Palace of São João da Praça (today a hotel); or at the Palace of Arroios in the district of that name in Lisbon, northeast of the old city centre. Also known as the Palace of the Lords of Pancos, the residence in Arroios was sold by the family in the early 20th century, and was demolished in the 1950s. The Duke also had a house a bit further out on this side of the city, the Palace of the Copeiros-Mores—the hereditary title (Grand Butler) of his de Sousa forebears—which was also called the Palace of Braço de Prata. Started in the 1590s, it was mostly constructed in the later 17th century, then was occupied in the 18th century by cousins, before it was reclaimed for the Duke of Terceira himself, then sold by his heirs in 1862 to the Portuguese railway company.

The heirs of the Duke of Terceira are a bit hard to trace at first, and since the fall of the Portuguese monarchy in 1910, there’s no legal body that confirms who does or does hold what title. In 1860, the heir to the titles and lands was considered to be a distant cousin Cristovão Manoel de Vilhena Saldanha, Senhor de Zibreira, who had been an Aide-de-Camp of King Miguel in the Liberal Wars of the 1820s-30s. Through his mother, Cristovão was the descendant of the 2nd Count of Vila Flor, from whom his line inherited the lordship of Zibreira, in the central river valley of the Tagus. Her mother in turn had been a daughter of the famousMarquis de Pombal, First Minister of Portugal in the 18th century. Cristovão’s father, however, was José Sebastião de Saldanha, 1st Conde de Alpedrinha, brother of Duke of Saldanha, one of the main political collaborators of the Duke of Terceira. Thus despite these grand connections on both sides, this family did not claim the title Duke of Terceira or Count of Vila Flor, but the claims did nevertheless pass through a daughter, Maria Benedita, to her son Tomás de Almeida Manuel de Vilhena who was given licence to use the title Count of Vila Flor by King Manuel II, who reigned briefly from 1908 to 1910. Vila Flor would later serve informally as head of Manuel’s government in exile, basing his operations from the (new) Palace of Vila Flor on the slopes of the Castle of São Jorge in Lisbon (while the monarch himself established his ‘court’ in Twickenham, west London).

This new Palace of Vila Flor, purchased in 1907, had initially been known as the Palácio da Costa do Castelo (the palace on the hillside of the Castle), built in the 17th century by courtiers of the royal household, the Cirne family. Located on a narrow street just around the corner from the Palace of Tancos (above), it passed through various ownership before it was bought by Vila Flor. The Count met with significant political and literary figures in this residence—he was himself a journalist and writer, as well as a politician, serving as governor of the districts of Braga and Madeira, and later as a senator in the 1920s—as did his son and grand-daughter, maintaining a sort of intellectual salon here well into the 1980s.

The Count’s paternal surname, Almeida, came from another old noble family, whose head was the Marquis of Livradio (created 1753). Tomás de Almeida added the name of his mother’s family, Manuel de Vilhena, and assumed the role of head of this clan in Portugal. Like many aristocrats in the 20th century, he was passionately interested in genealogy and heraldry, and became first president of the Portuguese Institute of Heraldry before he died in 1932.

His son, the 9th Count of Vila Flor, Francisco Maria de Almeida, was a professor of agronomics (the economics of agriculture), as well as a fencing champion. When he died in 1987, his titles and claims to headship of the House of Manuel de Vilhena passed to his daughter Luísa. She revived some of the other family titles, notably that of Count of Alpedrinha (created 1854, for the brother of the Duke of Saldanha, above) and Lord of Pancas, a much older title from a family that owned many properties all over the eastern edges of Lisbon, notably in the district of Marvila. Dona Luísa also revived use of the title Duke of Terceira. When she died in 1998, these titles and the various dynastic names (and those of her husband, Jaime Dias de Freitas, Count of Azarujinha, created 1890, and an extraordinary neo-gothic country residence near Évora), passed to her son Francisco Xavier Dias de Freitas, 5th Count of Azarujinha and 3rd Duke of Terceira, who died in 2007.

The current 4th Duke of Terceira is his son, Lourenço Manoel de Vilhena de Freitas (b. 1973), who is a professor of law at the University of Lisbon. He has worked as an advisor for the Portuguese government, and as a prominent member of the Portuguese Council of Nobility, also bears the titles from the various other families he represents: 12th Count of Vila Flor (Manoel de Vilhena), 4th Count of Alpedrinha (Saldanha), and 6th Count of Azarujinha (Dias de Freitas); while his young son and heir goes by the courtesy title ‘Master of Pancas’.

The Duke of Terceira name lives on today on the island of that name in the Azores in the lush botanical gardens located in the heart of the ancient port city of Angra de Heroísmo—the ‘Heroic’ tag added by Queen Maria II to honour the city from which her reign was launched back in 1832. At the top of the hill above the gardens is a monument commemorating the Queen’s father, Pedro IV, who championed the cause of constitutional liberalism in Portugal.