Once upon a time there was a Spanish outpost built in the far northern reaches of New Spain, in the Rio Grande Valley of the province of Santa Fe de Nuevo Mexico. Its founders named it after the Viceroy based in far-off Mexico City, the 10th Duke of Alburquerque. Some years later, the increasingly Anglophone settlers in the area dropped the first ‘r’. Today’s city of Albuquerque, New Mexico, has little memory of its connection to a small town and castle the dry barren lands of Extremadura, the frontier province between Spain and Portugal.

This proximity to the border makes the history of the name Alburquerque (Albuquerque in Portuguese) a bit more interesting, as it lent its name to a number of noble families linked via female lines who spread out all over the world and included famous empire builders in India and Brazil. The most famous to bear the name, Afonso de Albuquerque, established Portuguese naval supremacy in the Indian Ocean and was named Duke of Goa in 1515. The castle of Alburquerque, in Castile, however, belonged by that time to the family of La Cueva, founded by one of the most interesting figures in Spanish history of the 15th century, Beltrán de La Cueva, who allegedly fathered the Infanta Juana—called ‘la Beltraneja’ after her supposed father—who challenged the rights to the Castilian throne of the Infanta Isabella, more famous as half of the duo Ferdinand and Isabella. Perhaps as a ‘reward’ for providing King Enrique IV an heir, Beltrán was created 1st Duke of Alburquerque in 1464. These two families, Albuquerque and La Cueva, Portuguese and Castilian, were not closely related, but it is interesting to consider their histories together, in particular their legacies in India, Brazil and Mexico in the era of incredibly powerful colonial governors.

The castle of Alburquerque was founded by Castilian kings after the region was retaken from the Moors in the early 13th century, not far from the town of Badajoz. It controlled this new frontier area south of the river Tagus (Tejo) that became known as Extremadura (the ‘extreme’ south-western edge of royal control at this time. Its name likely comes from albus quercus (white oak), signifying cork oak grown in this region. Its first lord was Alfonso Téllez de Meneses, a Castilian warrior with origins near Palencia. His new lordship in this area of reconquest was granted by the King of Portugal, however (not Castile), Sancho I, as part of the arrangement of marrying the King’s illegitimate daughter, Teresa Sanches, in about 1213. Alfonso’s elder son founded the House of Teles de Meneses (one of the most powerful Portuguese noble lines in Middle Ages), while his second marriage produced João Afonso, who was active at both the court of Afonso III of Portugal and Alfonso X of Castile—a good example of the fluidity of these borders in this time period. The castle high on a rock above the settlement was built mostly by the 4th Lord, another João Afonso Teles de Meneses in the 1270s and then completed by his son-in-law Afonso Sanches de Portugal. João Afonso was also the Mordomo mor (head of the royal household) of King Diniz, and one of his chief advisors and diplomats. Connections with royalty abounded: the 4th Lord of Albuquerque’s wife was another Teresa Sanchez, illegitimate daughter of King Sancho IV of Castile; and later in the century, a cousin, Leonor Teles, was the mistress then queen-consort of King Ferdinand of Portugal.

With Afonso Sanches de Portugal taking control of the castle of Alburquerque, the lordship passed to a branch of the royal line itself. He was the illegitimate son of King Diniz, and elder half-brother of King Afonso IV. He was not only the firstborn son, however, he was also the favoured son of King Diniz, who created him Count of Albuquerque and arranged his marriage to the heiress of that lordship (Teresa Martins de Albuquerque) in 1304, and also successor to her father’s court office of Mordomo mor. When Afonso IV became king in 1325, he exiled his brother, and a few years later he was murdered. But the line continued, now in service of the kings of Castile: the 2nd Count of Alburquerque (Juan Alfonso ‘the Good’) was chief military officer of Alfonso XI, then Chancellor of the Kingdom of Castile and a favourite of his successor, King Pedro, from 1350. He only enjoyed this favour and this high office for a few years before Pedro ‘the Cruel’ turned on him and probably had him murdered. These were rough times to be a royal favourite!

But the line continued: the 3rd Count, a natural son (though described as legitimate in some sources), Martin, was appointed Governor of Murcia, but was also murdered by King Pedro; his brother Fernando Alfonso, the 4th Count, seems to have gone back into Portuguese service, and was appointed Grand Master of the Order of Santiago in Portugal. And at some point about now (the 1360s; I’m unclear on this), the County of Albuquerque is formally transferred back to the domains of the kings of Castile, not Portugal. The last of the original Portuguese house of Albuquerque died leaving only two natural daughters. The second of these, Teresa, married a Portuguese nobleman, Vasco Martins da Cunha, in about 1370, and transmitted her family name (not his) to their descendants—see below.

Meanwhile, the castle and estates at Albuquerque, now a Castilian fief, were given to yet another illegitimate royal line. Don Sancho Alfonso de Castilla was one of several illegitimate sons of King Alfonso XI. He was created Count of Alburquerque sometime between 1366 and 1373, and also served as chief military officer (Alferez mayor) of his half-brother Enrique II, founder of the royal house of Trastámara, in 1370. Not losing Portuguese connections, however, the Count married Beatriz de Portugal, daughter of King Pedro I (not the same guy as Pedro the Cruel). Perhaps Alburquerque was her dowry. The 2nd Count of Alburquerque died as a child, and the lands and title passed to his sister, Leonor de Alburquerque who, in 1394, married King Enrique’s second grandson, Fernando de Antequera, who, sort of against his will, was elected King of Aragon in 1412.

Initially, the County of Alburquerque was given to Leonor’s younger sons, Enrique and Pedro of Aragon, but in 1445, King Juan II of Castile (not their own brother King Juan II of Aragon…I know, this is really confusing!) took the estates away from this line and granted it to his favourite, Alvaro de Luna, Constable of Castile, who largely rebuilt the castle to its present appearance (so today it is called the ‘Castillo de Luna’). Like most favourites we’ve encountered so far, Luna fell from favour fast and hard and was executed in 1453, and the next king, Enrique IV, gave Alburquerque to his own favourite, Beltrán de la Cueva, as we’ve seen above. The castle would remain in the possession of this family for the next few centuries (though, interestingly, it would briefly return to Portuguese rule by conquest during the War of Spanish Succession). It has been administered as a Spanish national monument since early 20th century. So we need to turn to the family La Cueva, but first we can look at the last of the Portuguese lords who used ‘Albuquerque’ as a surname, not a title.

As we saw above, Teresa de Albuquerque married Vasco Martins da Cunha. Her daughters and grand-daughters mostly kept the name Albuquerque (while the sons continued their father’s patronymic line). So although by ‘purist’ genealogical reckonings, the family names changed first to Vaz de Melo then Gonçalves de Gomide, the next in this line of descent was known as Gonçalo de Albuquerque (d. c1462), Lord of Vila Verde dos Francos, a village in the hills north of Lisbon. His second son became the Grand Admiral of the Indian Ocean, ‘the Caesar of the East’, Afonso de Albuquerque.

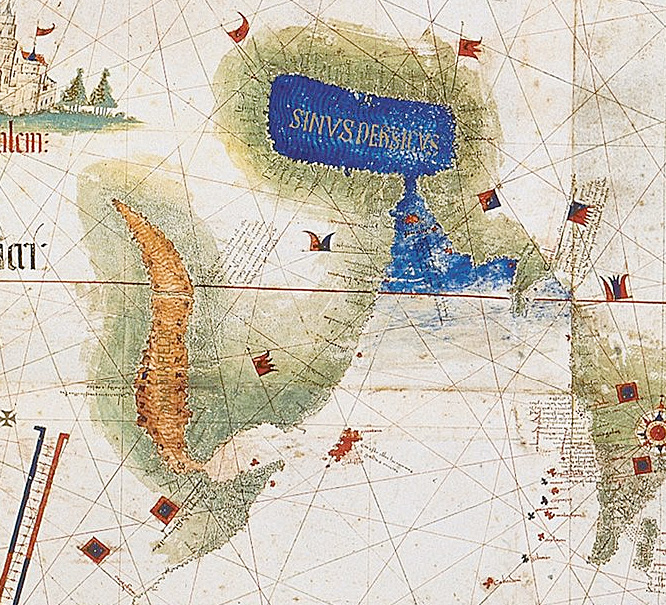

Young Afonso had been raised as a companion of the young Portuguese prince João, son of King Afonso V, who became King João II in 1481 and named his friend as his Master of the Horse and Chief Equerry. João II was one of the great builders of the Portuguese empire overseas, and this was continued by his cousin, King Manuel I, who, in 1506, appointed Albuquerque to command a fleet in the Indian Ocean (some say this appointment was to get his cousin’s former favourite, and thus a political rival, out of the country). Within a year, Albuquerque had conquered Muscat and Hormuz—the Muslim states guarding access to the Persian Gulf—then two years later defeated a combined Ottoman and Mamluk (Egyptian) fleet at the Battle of Diu. This was one of the turning points of world history that ended Ottoman domination of the Indian Ocean and turned it into virtually a Portuguese lake. In 1509 Albuquerque was appointed 2nd Viceroy of Portuguese India, and in 1510, conquered the city of Goa and moved the capital of the ‘Estado da India’ here (initially established a bit further south in Cochin on the Malabar coast). It would remain the capital of Portuguese India until 1961.

The city of Goa had been founded in the fifteenth century as a port on the banks of the Mandovi river by the sultans of Bijapur. It was built to replace Govapuri, which lay a few kilometres to the south and had been used as a port by earlier Hindu kings. Afonso de Albuquerque secured the loyalty of many of the majority Hindu population by removing the oppressive taxes of their previous Islamic rulers. Goa became the chief naval base for the Portuguese empire of the east, and from here, Albuquerque launched exploratory and military missions to Malacca and the Spice Islands. He established diplomatic ties with China, with Ethiopia and with the Persian Empire. Finally, in 1515, he was created Duke of Goa, the first non-royal dukedom in Portugal (though since it is not actually in the Kingdom, some sources do not count it), but he died shortly after.

Afonso de Albuquerque left an illegitimate son, Braz, born before his father departed for the Indian Ocean, and was later renamed Afonso by royal command to honour his late father. The 2nd Duke of Goa was appointed Overseer of the Royal Treasury for King João III, and served as President of the Lisbon City Council, in 1569. He built the Casa dos Bicos in Lisbon, and the Palacio da Bacalhoa in Azeitão, considered to be two of the finest Renaissance buildings in Portugal. When he died in 1581, the ducal title became extinct—though it was curiously resurrected by a descendant (through his daughter) many centuries later.

In 1886, João Afonso da Costa de Sousa de Macedo, 2nd Conde de Mesquitela, King of Arms of the Royal Household (senior herald), and 12th Armeiro mor (Chief Armourer) of Portugal, was created Duke of Albuquerque by King Luis I. His father the first Count had been recognised as the lineal heir to the family name Alburquerque, bearer of the arms of that house (and those of Costa, Sousa and Macedo), and in particular owner of the farm and residence at Bacalhoa. One of the curious Sousa de Macedo titles he held was Baron of Mullingar, in the peerage of Ireland, a title granted by King Charles II to Antonio de Sousa, a former Portuguese ambassador to England, in 1661. This new Duke of Albuquerque was a successful diplomat, and had been asked to be Minister of Foreign Affairs in 1870, and promised a dukedom at that time, but he turned both offers down. Finally accepting the ducal title in 1886, he died soon after in 1890. The title was considered to have been created for his lifetime only, but his brother and heir sometimes claimed the title Duke of Albuquerque, and so did some of his heirs in the 20th century.

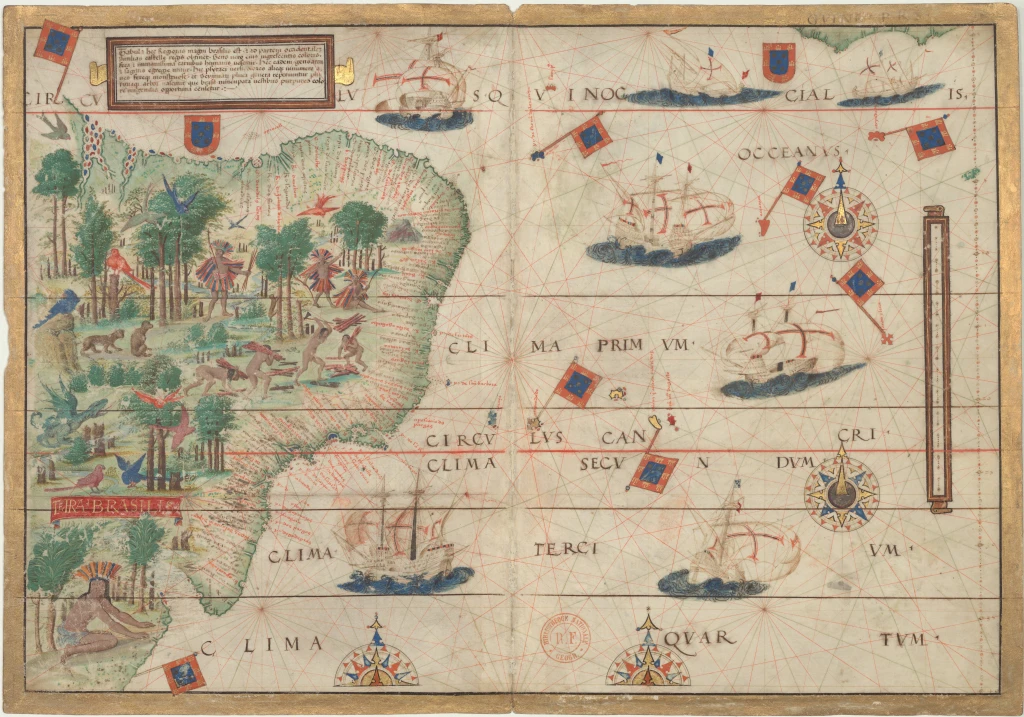

Back in the 16th century, there remained others who used the name Albuquerque, and spread it across the Portuguese empire. Some were descendants of Braz’s sister, who married into the House of Manoel (another illegitimate line of the House of Portugal) and were colonial administrators in India well into the late 17th century. Another fascinating figure is a cousin, Brites de Albuquerque, who followed her husband, Duarte Coelho, west across the Atlantic Ocean, in 1534 when he was appointed 1st Captain of Pernambuco, one of the divisions of the new colony of Brazil. Pernambuco, also known as ‘New Lusitania’, soon became one of the most lucrative Portuguese colonies in the Americas due to the production of sugar. Coelho founded a colonial capital, Olinda, and a port (today’s city of Recife), but had to travel back to Portugal several times to get financial backing from Portuguese merchants. On one of these trips, in 1554, he died, and his wife Brites simply took over running the colony, known as the ‘Captaincy’. This was a proprietary appointment, so Brites (known in Brazilian history as ‘Captoa’—the Lady Captain), maintained it for her sons until they came of age, and even after, as they returned to Portugal to serve in its wars in the 1570s. Altogether, she governed Pernambuco—quite effectively by all accounts—for over thirty years, until her death in 1584. She is considered to be the first female ruler of a European colony in the Americas. Her grandsons continued to be proprietary Captains of Pernambuco: Matias de Albuquerque (who took his grandmother’s surname, not Coelho) unsuccessfully defended the colony against the Dutch in 1634, and was briefly imprisoned back in Lisbon. When Portugal proclaimed its independence from Spain in 1640 under João IV, he was released and rallied to the cause; he defeated the Spanish at the Battle of Montijo, 1644, and was rewarded with a new title, Count of Alegrete. His brother Duarte, however, seems to have stayed loyal to Philip IV of Spain, and was created Marques de Basto and Vizconde de Pernambuco, though the colony remained in Dutch hands (not fully expelled until 1654). He died in 1658, in Spain, the last of his line.

Other interesting members of this branch of the family include Brites de Albuquerque’s brother, Jeronimo, who married a local indigenous princess, Muira-Ubi, a daughter of one of the Tabajara kings, who apparently saved his life, Pocahontas style, though like the story of Pocahontas, this is probably a romanticised version of the truth. She converted to Christianity and took the name Maria do Espirito Santo Arcoverde, but in true gallant colonialist style, he left her to marry a ‘proper’ Portuguese noblewoman, Felipa de Melo, in 1562. Apparently, Jeronimo de Albuquerque is remembered as the ‘father of Brazil’ since he left so many descendants with his surname. Another member of this branch of the family was Matias de Albuquerque, Captain of Hormuz, and Viceroy of Portuguese India, 1591-97.

By this point, the actual town and castle of Alburquerque in Extremadura was owned by the House of La Cueva, who had been propelled to the highest ranks of the nobility in just one generation due to royal favour. The family originally were minor nobles and royal officials in the town of Úbeda, near Jaén in Andalusia. Diego Fernández de la Cueva (d. 1473) held several administrative offices here and in other towns in the southeast, and became both a banker and a confidant of the king, Enrique IV. Towards the end of his career, he was rewarded with the title Viscount of Huelma (a nearby town). Before this, his family was honoured by the King’s request that his second son, Beltrán, serve as a page in the royal household. The King and Beltrán became very close, and the favourite was loaded down with gifts. The two friends were so close that some later historians accused them of homosexuality. These historians were supporters of the regime of Enrique’s half-sister, Queen Isabella, and you know what they say about history being written by the winners. The story goes that the King, so far unable to produce an heir, asked his friend to do the job: in 1462, Queen Juana of Portugal gave birth to a girl, the Infanta Juana. Beltrán was that same year married off to Mencia de Mendoza y Luna, the daughter of one of the richest men in the Kingdom, the Duke del Infantado, and niece of the powerful Cardinal Mendoza. This was certainly big step up for the relatively unknown Casa de la Cueva, and it is easy to see how this might be seen as ‘payment’ for services rendered. Beltrán was appointed head of the royal household, and some have called him an early example of a valido, or chief royal favourite.

Beltrán de la Cueva was also raised in rank one higher than his father, and created Count of Ledesma, a town and medieval castle in the west of Castile, near Salamanca. This wasn’t too far from the Portuguese border, nor was the town of Alburquerque, further to the south, given to Beltrán as a dukedom in 1464. At the same time he was given the important fortified towns of Roa and Cuéllar, both in Castile, not too far from the old court city of Valladolid. The new Duke of Alburquerque set about rebuilding and expanding all of these properties, but it was Cuéllar in particular that became the family’s main residence for the next two centuries.

The Castle at Cuéllar, a walled town in the Province of Segovia, was built in the 13th century. It was built as a royal castle, then given to the same earlier royal favourite we’ve seen before, Alvaro de Luna, then was confiscated and given by Juan II to his daughter, the Infanta Isabella, in 1453. When Enrique IV took it from his half-sister to give to his favourite, Beltrán, this really irked her. Nevertheless, she confirmed the gift to the La Cueva family in 1475. The castle’s structure, and the gardens behind it, were expanded into a palace fit for a duke in the 16th century, and became known as the Palace of the Dukes of Alburquerque. In the 17th century, most great aristocrats relocated their permanent residences in Madrid to be closer to the court, but Cuéllar remained the family’s favoured summer residence. It was gradually abandoned in the 19th century, after being occupied by French and then British troops during the Peninsular War. In the 20th century it was used as a political prison and a sanatorium, but more recently it happily opened to the public as a museum.

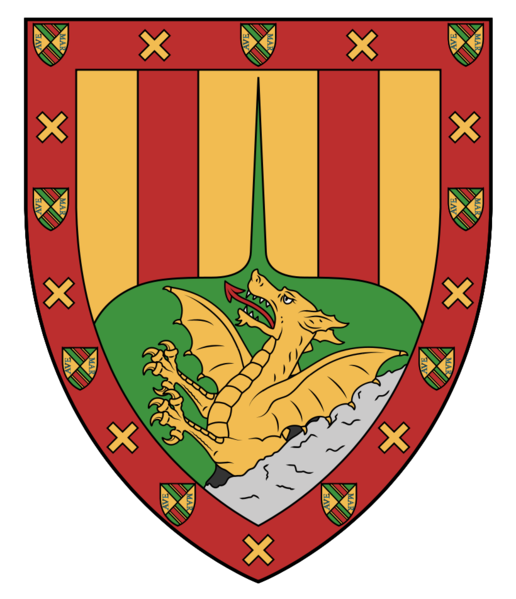

In 1467, the 1st Duke of Alburquerque fought for Enrique IV against rebels supporting a coup attempt by the King’s younger half-brother, the Infant Alfonso. Again he was rewarded, with another title, Count of Huelma, 1474. But the next year, the King died, and, against expectations, Alburquerque rallied to the cause of Isabella to succeed him—against the claims of his own reputed daughter, Juana (now called ‘la Beltraneja’, the little Beltrán). The new Queen of Castile thus confirmed his possession of Alburquerque, Ledesma and Huelma, and following the War of Castilian Succession (1475-79), he served her (and her husband, Ferdinand of Aragon), for the next decade, notably in the campaigns to conquer the Kingdom of Granada. He died the year that city was taken, 1492, and was buried in the Franciscan convent in the town of Cuéllar. This church became the sepulchre for the family for several generations, and though the buildings were destroyed in later wars, several of its sculpted treasures are now on display in the museum of the Hispanic Society in New York City. One of these clearly displays the coat of arms of the La Cueva family, now raised to the level of the grandees of Spain: on the left side of the altar, their arms bear a distinctive wyvern (a two legged winged dragon; in some it is golden, but in other versions it is green; and in some it is emerging from a rock or mountainside); the 1st Duke’s arms also bore small versions of the arms of the Mendozas (his wife’s family) in the border around the edges.

Other family members were also put into prominent positions, notably the Duke’s younger brothers, Gutierre (Bishop of Palencia, 1461), and Diego (Governor of Cartegena, 1460). In 1476, Beltrán married as his second wife, a daughter of the 1st Duke of Alba—thus really securing his family’s place at the top of the aristocratic hierarchy—and at the same time his son married his new step-mother’s sister. Best make these new marital links firm! A third marriage was made in 1482 to the widowed Duchess of Escalona, his first wife’s cousin, Maria de Velasco y Mendoza, daughter of the former Grand Chamberlain of Enrique IV—when she was widowed for a second time, Queen Isabella created her Duchess of Roa, 1492, just for herself, and although the castle and lordship of Roa passed to her sons (see below), this dukedom did not (and some recent historians have argued that there never was an actual duchy of Roa, it was just a title of honour given to a widow who was already of ducal rank).

The 2nd Duke of Alburquerque, Francisco, is not known for very much, but did serve the first Habsburg king, Carlos I (aka, Emperor Charles V) in his various campaigns, and in 1520 was amongst the first to be promoted to the new rank of ‘Grandee of Spain’. He continued to develop the various castles given to his father, including the Castle of Colmenar, which was renamed Mombeltrán (Monte Beltrán), near the city of Avila in western Castile. Here he fashioned a gallery, a newish architectural feature coming to Spain from Italian Renaissance influence—a place to promenade and hang family portraits.

The 2nd Duke had nine children, who all (boys and girls) served in the household or the armies of the Charles V in some capacity or another. The two eldest, the 3rd Duke (after 1526), Beltrán, and Luis in particular, fought both at home and abroad (Luis especially, at the siege of Vienna by the Turks in 1526; he also held a court position as Captain of the Guard). The 3rd Duke had impressed Charles V in his early campaigns against the French in Navarre (the French were trying to liberate that Kingdom, recently conquered by the Spanish), so he was named Captain-General of the Spanish Army defending the northern frontiers, 1522, and later Viceroy and Captain-General of Aragon. He also led some diplomatic missions abroad, where he met King Henry VIII, and the English king, also impressed with his leadership skills, invited him to London, fitted him out with a large household, and appointed him Generalissimo of the English Armies in 1544 in the campaigns to try to capture Boulogne. Later in life the Duke would be Viceroy of Navarre, 1552-60. Meanwhile, the 3rd Duke’s brother, Bartolomé, became a prelate, and an influential priest in Rome, friend to Loyola and patron of the first Jesuit church in Rome in 1544. That year he became a cardinal. He remained in Rome for the rest of his career, except for a brief stint as Viceroy of Naples, from October to June, 1558/59.

In the next generation, the 3rd Duke’s eldest son was already in military service in the lifetime of his father, and was created Marques of Cuéllar in his own right in 1530. He fought in campaigns in North Africa, then succeeded his father in 1560, but was only 4th Duke for three years, and was succeeded by his brother Gabriel, who was also a soldier, notably leading the defence of the North African city of Oran against the Ottomans in 1556. As 5th Duke of Alburquerque, he was Viceroy of Navarre in 1560, then Governor of Milan—a key position in the Spanish Monarchy—from 1564 until his death in 1571. He left behind this amazing portrait, by Moroni, from about 1560.

But the 5th Duke also left behind a daughter, Maria, who tried to claim the family lands and titles. After a family scuffle, the courts awarded these to her first cousin, Beltrán III de la Cueva, who in proper early modern aristocratic style, married his other cousin, the daughter of the 4th Duke, so there wouldn’t be any other rival claims to the ducal title, castles and estates. He too, as 6th Duke, would be Viceroy of Aragon, 1599 to 1602. And so too did his son the 7th Duke hold the most senior government positions in the Spanish Monarchy: Viceroy of Catalonia, 1615-19; Viceroy of Sicily, 1627-32; President of the Council of Italy, 1630, and so on. In Catalonia in particular he was known as a rigorous administrator, though perhaps too rigorous, suppressing disorder, but also significant freedoms.

Four more sons followed as the 17th century matured (three of them with the colourful and Christmassy names of Gaspar, Melchor and Baltasar). The eldest, Francisco, became the 8th Duke of Alburquerque in 1637, while the second and third sons forged careers in the army and navy, respectively. The 4th son, Baltasar, Count of Castellar by marriage, was much later in life appointed Viceroy of Peru (1674-78)—he spent much of his time in South America sending expeditions south along the Pacific coast to secure it from English and Dutch incursions. He also put down an indigenous revolt led by a self-proclaimed Inca prince. But this was not the first time the La Cueva family became involved in the affairs of the New World. One female cousin (perhaps two) had accompanied her husband as governor to the Yucatan in Mexico. The 8th Duke of Albuquerque himself became Viceroy of New Spain, 1653-60. His time in government was marked by a serious attempt to defend the eastern coasts of Mexico during war with England, and more of an effort to increase trade with the Philippines and Asia. He pushed for the completion of the Cathedral in Mexico City. When he returned to Spain, he was named Ambassador Extraordinary to the Imperial Court in Vienna, accompanying the Infanta Margarita Teresa to her marriage to Emperor Leopold in 1666. He then went south, and was Viceroy of Sicily, 1668-70, and finally Mayordomo mayor (head of the household) of King Carlos II, 1674-76. He had only a daughter, who, once again, married her uncle, Melchor de la Cueva, who succeeded as 9th Duke, but only for 10 years, dying in 1686.

The real heir of the 8th Duke and previous Viceroy of New Spain in the La Cueva family, was his nephew, Francisco, 10th Duke of Alburquerque. His early years were spent in the navy, as Captain-General of Granada and the coasts of Andalusia. When Carlos II left the Spanish Monarchy to the French prince, Philip of Anjou, in 1700, the Duke was an immediate supporter of the new Bourbon regime, and was rewarded by an appointment to his uncle’s old post as Viceroy of New Spain in 1702. He repressed any lingering loyalty to the Habsburg Dynasty in Mexico and raised lots of money to send back to Spain in support of the Bourbon cause in the War of Spanish Succession. He also brought a new Bourbon magnificence (in contrast to more sombre Habsburg style) to the viceregal court in Mexico City. Alburquerque also strengthened the navy and coastal defences (once again against English attacks), and continued to expand Spain’s colonial reach northwards into North America—he supported Jesuit missions to California, and in 1706 approved a new settlement, which was named after him, in the province of Santa Fe de Nuevo Mexico (ie Albuquerque, New Mexico). The Viceroy also established another new northern outpost, named for his family’s spiritual home back in Spain, San Francisco de Cuéllar, in 1709 (today known as Chihuahua). But of course not everything can be painted as rosy successful history; his regime also brutally suppressed a rebellion by the Pima Indians in this area of northern Mexico. He was recalled to Spain in 1711 and served at court as Gentleman of the Chamber of King Philip V until his death in 1724.

The 11th Duke of Alburquerque stayed much closer to the royal court in Madrid. In 1742, he was appointed Caballerizo mayor (first equerry) of Prince Ferdinand, and stayed in this role once the prince became King Ferdinand VI in 1746. The Duke died in 1757, leaving behind only a daughter, whose husband tried to claim the ducal succession after her death in 1762 for their son (but he too died young, in 1779); and a sister, the Marquesa de los Balbases, whose heirs ultimately inherited the dukedom, but not yet.

As noted above, by the 17th century, most of the Spanish grandees made their permanent base in Madrid to be closer to the court. Several of these dukes of Alburquerque lived in the Royal Palace, the Alcázar of Madrid, as their offices required constant attendance on the king or the queen. There is a suggestion that there was an old residence from the 16th century on the Calle Mayor, at the intersection of Calle de Bailén, which would put it at about the location of the Palace of the Duke of Uceda, built in 1613, which was later converted into the buildings of the Council of State (which it still is). In 1645, the 8th Duke acquired by marriage (I think) a new residence near the Royal Monastery of La Encarnación, a few streets northeast of the royal palace. He had married the heiress of Lope Diez de Armendáriz, 1st Marques de Cadreita (1617), born in Peru and later another Viceroy of New Spain (1635-40), whose estates were in Navarre. The 8th Duchess (Juana) served as a lady-in-waiting in the households of queens Isabel, Maria Luisa and Maria Ana, so needed a residence close to the court.

The La Cueva family also possessed a house in Hortaleza, at the time a ‘garden village’ on the outskirts of Madrid (now one of the city’s districts), where the 10th Duke died. The 11th Duke was born in the house near La Encarnación, but spent much of his time in Hortaleza, in a garden residence known as the ‘Palacio de Buenavista’.

After the death of the 11th Duke in 1757, the inheritance was split up. The Ducal title, being a male-preference title, passed to the next male heir, the Count of Siruela. The County of Siruela, in Extremadura, was created in 1470, and passed by marriage to a younger son (the son of the Duchess of Roa, above) in the early 16th century. The Counts of Siruela (using the compound surname Velasco de la Cueva) were a mid-level court family in the succeeding centuries. The 12th Duke of Alburquerque was a Spanish field marshal and died only a few years after he had successfully claimed the title. His son, Miguel, not only inherited the main La Cueva titles (Alburquerque, Cuéllar, Ledesma and Huelma), but also the Marquisate of La Mina (1681), with lands near Seville, created in 1681 for his Guzmán-Dávalos ancestors. He was a courtier, Captain of the Royal Guards Halberdiers and Gentleman of the Chamber of Carlos III and Carlos IV. In 1792-95, as tensions were heating up along the northern border with Revolutionary France, Alburquerque was appointed to an important role as Captain-General of Aragon. He acquired a new palace in Madrid in about 1765, on the Calle de Santa Isabel, a new construction built in the gardens in the old convent of that name (near today’s Atocha Station); then expanded and remodelled it in the 1790s. By the 19th century, it had passed out of the family and was possessed by the Duke of Fernán-Núñez, by which name the palace is known today.

The 13th Duke died in 1803, and was succeeded by his son, José Maria, a soldier who had been rapidly promoted in the 1790s, a brigadier by age 19. In 1808, as Spanish patriots began to fight back against Napoleonic occupation, the 14th Duke of Alburquerque was appointed Commander of the Army of Castile, then promoted to field marshal then lieutenant-general by 1810, at the head of the Army of Extremadura. He secured the city of Cadiz as a base for the Regency Government (nominally supporting the exiled King Ferdinand VII, but really trying to create its own liberal constitution for a renewed Spain), and was named governor of that city, then Captain-General of Andalusia and President of the Junta of Cadiz (the temporary ruling royalist government). But he soon clashed with others on the Junta, and was sent to London as its ambassador—this was a useful posting as he had made lots of close associations with British army officers helping to liberate Spain, including the Duke of Wellington. But he died soon after, still in London, where he was given a funeral with honours in Westminster Abbey.

With the death of the 14th Duke of Alburquerque in 1811, without a legitimate male heir, the succession was once again contested, for nearly 20 years. His sister was able to claim the successions to Siruela and La Mina, but not Alburquerque. There had been other lines of the House of La Cueva. The senior line (from all the way back in the 15th century, the elder brother of the first Beltrán), were created Marques of Bedmar in 1614, but went extinct in the male line in 1723; the last of these was a significant figure in the Spanish Monarchy: Isidro, 5th Marques de Bedmar, Supreme Commander of the Army in the Spanish Netherlands from 1697, and interim Governor-General of the Low Countries, 1701-04 (a position usually reserved for nobles or princes of much higher rank), and finally Viceroy of Sicily, 1705-07, and Minister of War, 1709. A cadet branch in the 16th century were created Marques of La Adrada (1570), but was extinct by the end of the century. The Line of Bedmar did have its own cadet branch, the counts of Guadiana (who maintained a palace back in the old dynastic hometown of Úbeda), and they continued into the 19th century, so their claims were amongst those that muddied the waters in the Alburquerque succession. It took the courts until 1830 to make a full settlement, but already in 1811 Manuel Miguel Osorio Spinola de la Cueva was calling himself the 15th Duke of Alburquerque. He died before the ruling, so sometimes the numbering systems are off from this point. Manuel Miguel, of the House of Osorio, was already an interesting mixture of two noble lines, from his maternal grandparents, Ana Catalina de la Cueva, sister of the 11th Duke, and her husband Ambrosio Spinola, 5th Marques de los Balbases and 5th Duke of Sesto; but also from his father, the 14th Marques de Alcañices (Osorio). What’s more, he married the heiress of the Duke of Algete (cr. 1728), so this title (and its estates, just north of Madrid) passed to his son as well when he finally formally succeeded as 15th Duke of Alburquerque in 1830.

The dukes of Alburquerque in the 19th century were thus a conglomerate of Spanish (and Italian) houses. The Osorios were an old noble family from León. Their main titles were the marquisate of Astorga and the county of Altamira, but they also inherited the duchy of Medina de los Torres (so they will get a separate blog post). Their arms, two red wolves on gold, were now paired with those of La Cueva. The senior line of the Osorios had inherited in 1741 the marquisate of Alcañices (in Zamora Province, created 1533 for the Enríquez de Almansa). The house of Spinola was originally from Genoa, but had settled in Spain after the creation of their marquisate of Los Balbases, 1621, in Burgos Province—they also retained significant lands granted to them by the King of Spain in the Kingdom of Naples, notably the Duchy of Sesto, 1612 (northwest of the city of Naples). With these added dynastic lines came significant new properties in and around Madrid. While the house in Hortaleza passed out of the family, as did the palace in Madrid near Atocha, an impressive new residence was gained: the Palacio del Marques de Alcañices (or Palacio de Sesto). This was located in a prominent place on a corner where the Calle de Alcalá intersects the Paseo del Prado, two of the grand boulevards developed on the eastern edge of the old city in the reign of Carlos III. The palace was built sometime in the late 17th century, and purchased by the Osorios in the late 18th century; they would later sell it in 1882, and the building would be demolished to make way for the Bank of Spain.

The 15th Duke of Alburquerque, also Duke of Sesto and Duke of Algete, was a major horse breeder, and firmly established his family as part of the Spanish ‘horsey set’, which they still are today. He was also a courtier, as Mayordomo mayor for Prince-Consort Francisco de Asis (husband of Queen Isabel II), and then Ayo (governor) for their son Prince Alfonso after his birth in 1857. The Duke died in 1866, leaving this role to his son, known already as the Duke of Sesto (he was also called ‘Pepe Osorio’ or ‘Pepe Alcañices’), one of the most interesting characters in royalist circles of 19th-century Spain.

José Osorio y Silva, 16th Duke of Alburquerque, had already started to establish his political name as Duke of Sesto, when he was Alcalde (mayor) of Madrid, 1857-64. After his father’s death he took over the fatherly role to the Prince of Asturias, as his Mayordomo and Gentleman of the Chamber—he would become one of Alfonso’s closest advisors when he later became king, and appropriately, Director of the Royal Stud Farm and the King’s Montero Mayor (Master of the Hunt). Across his long life he would be director of a number of horse-related government offices or public societies, for example, he was President of the National Society for the Promotion of Horse Breeding (founded by his father), from 1886 to his death in 1909.

But it is as a chief supporter of the Bourbons that Alburquerque made his mark. Isabel II was forced to give up the throne in 1868, and went into exile in France. The Duke of Alburquerque purchased a palace for her in Paris, renamed the Palacio Castilla (later better known as the very grand Hotel Majestic), and lent the royal family the use of his house at the fashionable seaside town of Deauville. In 1870 he persuaded the Queen to formally abdicate the throne in favour of young Alfonso (whose education he’d been put in charge of), in hopes for a better chance at a restoration. The Duke spent millions in his efforts on behalf of the Bourbons, and was active in rallying the nobility of Spain to the Borbonista cause. His wife too was active in this regard: Princess Sofia Troubetskoy, formerly married to the Duc de Morny (half-brother of Napoleon III)—and rumoured to be the love-child of Tsar Nicholas I—was one of the most beautiful, cosmopolitan and fashionable women in Madrid. In 1871, she led the ‘Rebellion of the Mantillas’, a movement which aimed at alienating the newly imposed King Amedeo of Savoy and his wife in Madrid society. Their home on the Calle de Alcalá became the main gathering place for ‘Alfonsistas’. The Duchess was also reputedly the first to bring Christmas trees to Spain…

After a brief republic, Alfonso XII was indeed restored in December 1874, and the Duke of Alburquerque was appointed Jefe Superior of the Royal Palace, basically head of the royal establishment. After Alfonso XII’s early death in 1885, he tried to retire, or at least to retreat to running only the Royal Stud Farm, but was convinced to stay on as mayordomo for the young royal princesses, and was then appointed Gentleman of the Chamber to the new king, Alfonso XIII, born in the Spring of 1886. But he increasingly clashed with the Queen Mother, Maria Christina of Austria, who accused him of stealing money from the royal treasury—once again in this story we see the pretty poor extent of royal gratitude towards favourites! So he donated more of his personal wealth to her, including the Duchy of Sesto and other lands in Italy (1889). He retired from court—though continued to have a role in public affairs, as Spanish representative to various international expos, like that in Paris of 1900. He had sold the Palace on the Calle de Alcalá, and died in a palace a bit to the north, on the Paseo de Recoletos, a grand building located across that broad avenue from the National Library of Spain. Built for the Duke of Sesto in 1865, it would remain the family residence until sold to the General Council of Lawyers in the 1990s.

The 16th Duke of Alburquerque and 9th Duke of Sesto left his titles by a will to his great-nephew, Miguel Osorio. He was appointed one of the ‘Gentilhombres Grandes de España’, the more exclusive rank of Gentleman of the Chamber, reserved for only the highest ranking noblemen and those closest to the King. He was briefly elected deputy to the Cortes for Alcañices in the 1920s, but otherwise kept a fairly low profile. His son, the 18th Duke, another Beltrán, was head of the household of the Count of Barcelona (the exiled head of the royal family) from 1954 to that prince’s death in 1993 (himself dying a year later). His fame came from not from his service to the Bourbons, but from the other great family passion: equestrianism. He was considered one of the best horsemen in Europe, competing in two Olympics (Helsinki 1952 and Rome 1960), and later at several Grand National events in England. Later Alburquerque was a trainer, and, like his predecessors, President of the Society for the Promotion of Horse Breeding in Spain (1985-88). In his obituary he was referred to as ‘the last Spanish cavalier’.

The 20th-century dukes continued to live in the Palacio del Duque de Alburquerque on Paseo de Recoletos. But today’s Duke, the 19th (Juan Miguel, born 1958) lives mostly at his farm El Soto de Mozanaque, where he—unsurprisingly—tends horses. This farm, in Algete, about 30 km northeast of Madrid, was built by the 1st Duke of Algete as a hunting lodge in the early 18th century. The 19th Duke of Alburquerque has restored it and opened it up for use for weddings and other events.

(images from Wikimedia Commons)

One thought on “Dukes of Alburquerque: Royal Favourites and Colonial Governors”