In the 18th century, political boundaries and national identities were a bit more fluid than they became in the 19th and 20th centuries. A person of great talent could move around the European continent and acquire position and status in a land very different from his or her place of origin. Such is the interesting case of Sir John Acton, one of the great figures of the history of the Kingdom of Naples in the late 18th century and the era of Napoleon, Nelson and the famous beauty Emma Hamilton. Acton established a dynasty that persists in southern Italy today, picking up a princely title in the 20th century, and today occupying one of the finest palazzi in Naples, Cellammare.

English-speaking lovers of Italian history, like me, first came across the name Acton through the author and dilettante Sir Harold Acton, a prominent member of the Bright Young Things in 1920s London, who wrote deliciously gossip-filled books about the last of the Medici (1930) and the last of the Bourbons of Naples (1956 and 1961). When he died in 1994, he donated his villa outside Florence to New York University to encourage the study of Italian art and history.

Harold Acton was a very junior member of an Anglo-Italian family of baronets and later barons. But one of his cousins was granted use of his mother’s princely title in the 1930s, and his heirs now bear the title Prince of Leporano and Duke of Spezzano, thus bringing them into the sphere of this blogsite.

There are early traces of a landowning family in Shropshire in the 13th century, who held local offices and assumed the name ‘de Acton’. There’s a village with this name (possibly from ‘oak town’) in the southwest part of that county, not far from the Welsh borders. But their seat became Aldenham Park, a short distance to the northeast, closer to the county town of Shrewsbury (though there are also nearby villages of Acton Burnell and Acton Round), and not far from Wenlock Edge. Their local constituency was Bridgnorth, and numerous Actons were Members of Parliament from there across the centuries.

The fortified manor house at Aldenham was acquired by the family in 1456, and replaced by a more modern country house in the 17th century then augmented several times in the 18th and 19th centuries, until it was let out then sold by the mid-20th century. It remains in private hands today.

At the start of the 17th century, there were two Acton cousins: Walter held the estate of Aldenham, while William, whose father had become a merchant in London, rose to the position of Sheriff of London in 1628, and in 1629 was created a baronet. In September 1640, he was elected Lord Mayor of London, but his election was nullified by Parliament only a month later, as he was seen as too royalist. He died without a male heir in 1651. By that time, Walter’s equally royalist son, Edward, had himself been created a baronet, for Aldenham (1643). Sir Edward Acton was also MP for Bridgnorth and Colonel in the Regiment of Royalist Dragoons

The Baronets Acton continued in succession, usually sitting in Parliament for Bridgnorth. They added a smaller, but more attractive (I think) cottage at Acton Round, used for the heir or for dowagers, but mostly abandoned by the 19th century (and now owned privately by a different family).

The 5th Baronet died in 1791 with no male heir, so the title passed to his cousin, the family’s most famous member: Sir John Acton. John had been born in Besançon, France, where his father, a physician, had settled, the hometown of his wife’s family. His uncle John was a commander in the Tuscan navy, and young John joined him in this service and saw action in the 1770s in battles against the Barbary states in North Africa. By 1775 he was a commander, and led the Tuscan contingent in a (fairly disastrous) Spanish raid against Algiers. Tuscany was at this time governed by Grand Duke Leopold of Lorraine, whose brother was the Holy Roman Emperor, and whose sister, Maria Carolina, was the Queen of Naples. In 1775, the Queen began to assert her authority in the Kingdom—she was well educated and her husband, King Ferdinand IV, was not … embarrassingly so—and in 1778 she asked her brother to send Acton to Naples to re-organise its royal navy. He was rapidly promoted and soon named Commander-in-Chief of both the Army and the Navy, and Minister of the Marine Forces, and by the end of the next decade, both services were in a much better state. But Acton’s influence was much broader—together with the English ambassador, Sir William Hamilton, he aimed to shift Neapolitan diplomatic policies away from Spain and France (the other two Bourbon monarchies), and more towards Austria and its ally, Great Britain. His government portfolio also expanded: in 1780 he was Minister for War, and soon thereafter Minister of Commerce—and by 1789, he was First Secretary of State, essentially Prime Minister.

Acton was not universally loved, sharply raising taxes to pay for this new navy, and attempting to bring Naples and Sicily into the more Enlightened spirit of the age in terms of government reform and limits to the Church. The high aristocracy, who had always completely dominated Neapolitan affairs, disliked his relatively low birth, and naturally accusations flew about him and the Queen being lovers. They disliked the influence the British admiral, Horatio Nelson, had over the Neapolitan fleet (and the influence of his lover, Hamilton’s wife Emma, over the Queen). But Nelson’s defeat of the French Mediterranean fleet in 1798 temporarily saved Naples from invasion. A few months later, however, Nelson transported the King and Queen, Acton, and the Hamiltons, to the Kingdom’s second capital, Palermo, in Sicily. The French established a republic in Naples (the Parthenopean Republic), from January to June 1799, after which Acton (now Foreign Minster too) re-established royal authority in Naples with a severely authoritarian and repressive regime. In 1804, again feeling threatened by Napoleon, the King was convinced to sack Acton, sending him to Sicily and giving him a duchy (Modica, which he later renounced). He was soon recalled, but when the French armies invaded Naples, he and the royal family fled once more to Palermo, where Sir John died in 1811.

Late in life, Sir John Acton decided to found a dynasty. At age 63 he married his 13 year-old niece Mary Ann Acton, daughter of his brother Charles, and they swiftly had three children: Ferdinand, Charles and Elizabeth. Sir John had two brothers, Charles and Philip, who both also made careers in the Neapolitan military. Charles founded the junior branch of the family, to which we will return later.

The eldest son, Ferdinand Acton, 7th Baronet, was known by his second name, Richard. Only a child when his father died, he was sent with his brother to be educated in England. He then returned to Naples in the 1820s, where he commissioned a magnificent neoclassical villa in the neighbourhood known as Chiaia, the fashionable ‘Neapolitan Riviera’ just west of the centre of the city. It still sits at the end of a magnificent garden; today known as the Villa Pignatelli, named for its owners since the 1860s (after having first been sold to the Rothschilds in 1841). Willed to the state in 1952, it today houses an art museum with a special focus on coaches and carriages.

In 1832, Sir Ferdinand Richard Acton, an English baronet, joined his family more firmly to the higher aristocracy of Europe by marriage to Baroness Marie-Louise von Dalberg, whose father had been the 1st Duc de Dalberg, a curious blend of German and Napoleonic aristocracy, nephew of the last Archbishop-Elector of Mainz, who entered service of the French Empire, then represented Louis XVIII at the Congress of Vienna in 1814. Marie-Louise’s mother was a member of the very grand Genoese dynasty, Maria Pellegrina Brignole-Sale. As his wife was a grand heiress to the Dalberg lands in France and Germany, he soon added her surname to his own. Eventually, their son would also inherit one of the Brignole-Sale titles, Marchese of Groppoli, a formerly autonomous fief in the mountains between Liguria and Tuscany, with a crumbling castle up in the mountains.

Sir John’s second son Charles, whose second name reflected the patron saint of Naples, Januarius, joined the Church at a young age and served as a Vice-Legate (deputy governor) in Bologna before being promoted Cardinal in 1842. He was very close to popes Pius VIII and Gregory XVI, and often served as a trusted go-between with other heads of state, and was offered higher posts like the archbishopric of Naples. Never of strong constitution, Cardinal Acton weakened and died in 1847, only 44 years old.

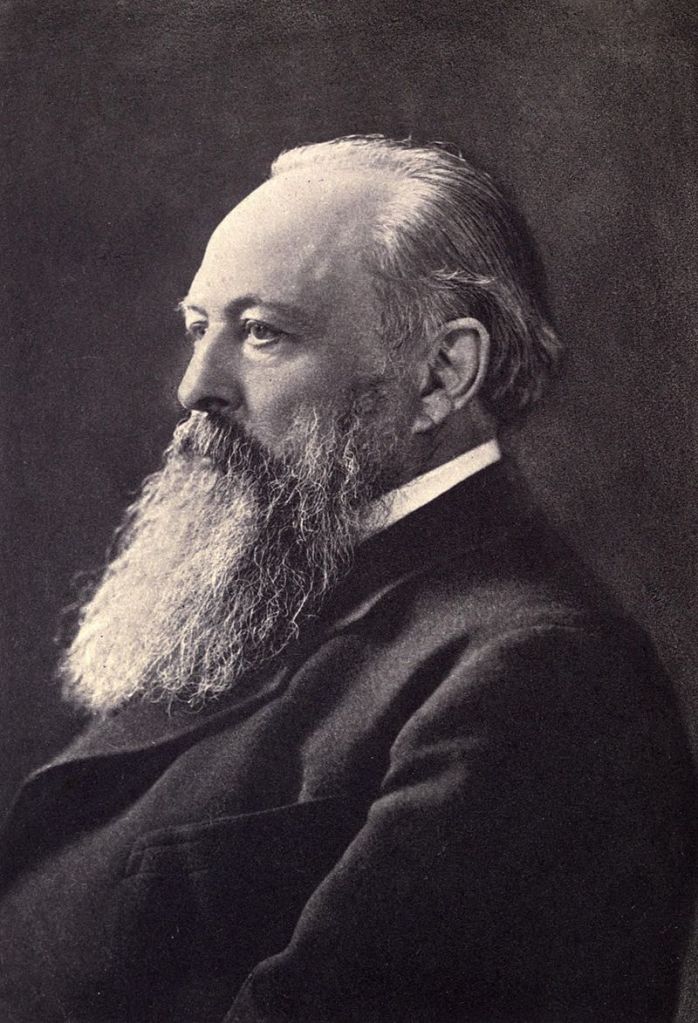

His nephew, Sir John Dalberg-Acton, became the second most remembered member of the family, re-establishing his family’s prominence in Britain. Yet as heir to the Dalberg estates in the Rhineland, he was also Lord of Herrnsheim, a castle and park outside the city of Worms. Herrnsheim had been the seat of the hereditary chamberlains of the bishops of Worms (and adopted ‘Kämmerer von Worms’ as their surname until they changed it to von Dalberg). An ancient medieval castle was rebuilt in the 1460s, then again after a terrible fire in the early 18th century; it was renovated by the Duke of Dalberg in 1809, and again by his daughter, Lady Acton, in the 1830s-40s, notably adding a library in the ancient tower, with an amazing spiral cast-iron staircase—the first of its kind in Germany.

Dalberg-Acton, 8th Baronet, sold Herrnsheim in 1883 (it today belongs to the city of Worms), and by then was also the 13th Marchese di Groppoli. But by this point, his career was firmly in England, where he had taken up the old family seat in Aldenham and was elected as MP for Bridgnorth (as usual) in 1865 (having previously held a seat representing Carlow in Ireland). He was a Liberal, an ardent supporter of Catholic emancipation and home rule in Ireland, and a friend and ally of Prime Minster William Gladstone. Gladstone urged Queen Victoria to raise him to the peerage, as Baron Acton, in 1869, in part to secure his alliance as he negotiated religious policy with Catholic Rome. Acton became known as a writer and historian, focusing on ideas about the compatibility of the ideals of freedom and traditional religion. He was the editor of the Catholic monthly The Rambler, and helped start the English Historical Review, one of the earliest and most prestigious academic journals, but he never published very much himself—his most famous quote comes from a letter he wrote to a colleague in 1887: ‘Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely.’ Having been denied entry to Cambridge University as a student, it must have been a great pleasure to be appointed late in life as Regius Professor of Modern History there in 1895. He died in 1902, and is buried at the residence of his wife’s Bavarian family, the counts von Arco.

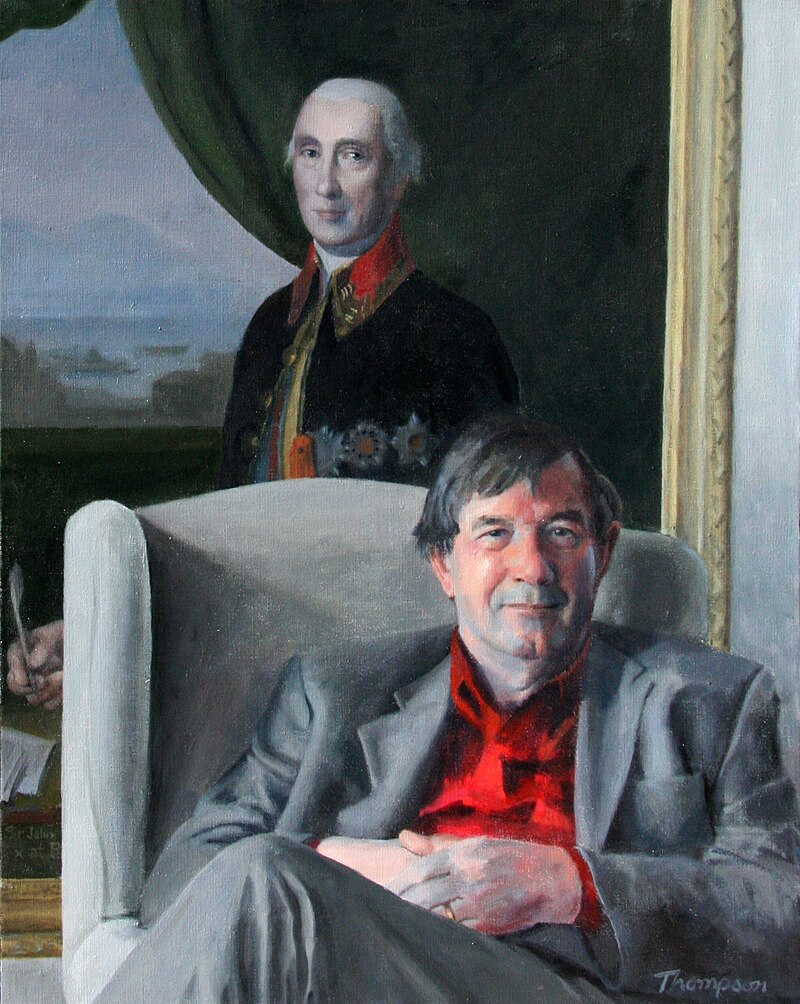

The 2nd Baron Acton, born in Germany, educated in England, with estates in Italy, naturally became a diplomat, with posts all over Germany, then serving as Britain’s first ambassador to independent Finland in 1919. He was a lord-in-waiting to both Edward VII and George V, and died relatively young in 1924. He had married another heiress, Dorothy Lyon, of Appleton Hall in Cheshire, so the next generation added another name to become Lyon-Dalberg-Acton. Appleton Hall is near Warrington, and became a school in the 1930s; it was demolished in the 1960s, but the estate is now part of the Bridgewater High School. The Acton barons continued to be involved in politics and the Catholic church for the rest of the 20th century. The family had moved to Southern Rhodesia in the 1940s (selling Aldenham), where they raised cattle. The 4th Baron, Richard, married a campaigner against white rule in Rhodesia, and briefly worked in the transitional regime of a newly independent Zimbabwe, clearly continuing his family’s traditional devotion to liberal democracy. But he left once the regime there became oppressive and took up his seat in the British House of Lords. He became an active Labour politician, and was created Baron Acton of Bridgnorth in 2000 to allow him to continue to sit in the House of Lords—whose hereditary nature he had worked to end. His brother Edward was Professor of Modern History specialising in the Russian Revolution at East Anglia University, and later its Vice-Chancellor, retiring in 2014. The current Baron Acton (and 17th Marchese di Groppoli) was born in the 1960s and is a farmer and author (of cookbooks) in Gloucestershire.

So there are several historians in this family, which leads us back to Sir Harold Acton and back to Italy.

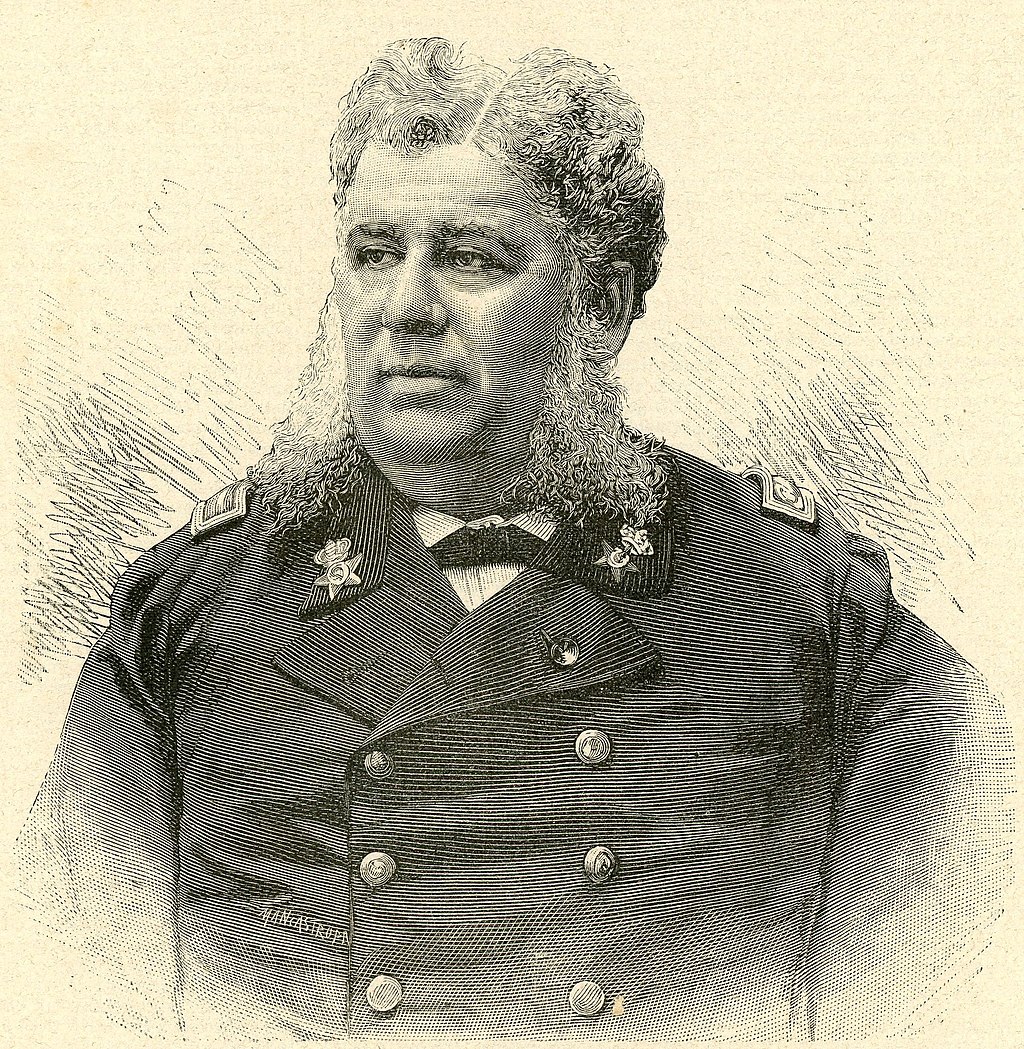

The younger branch of the House of Acton was founded by Sir John’s younger brother Joseph, who also served in the Neapolitan navy. Like his nephew Ferdinand, he married into the higher European nobility, a noblewoman from Limburg (Baroness Berghe von Trips), as did his son, Charles (or Carlo), also a Neapolitan military commander, who married a French noblewoman from the House of Albon in Dauphiné. The European aristocracy of the early 19th century were trans-national in a way almost unimaginable today. Charles had thirteen children, so there are numerous branches of the Actons around today, in England, Italy and elsewhere. Two of his sons, Guglielmo and Ferdinando became admirals; both became Minster of the Marine of the newly united Kingdom of Italy (1870-72 and 1879-81), and in fact both married noble sisters in Naples. Their sister Laura married Marco Minghetti, one of the first Prime Ministers of united Italy (and going further, her daughter from a previous marriage married Prince von Bülow, Chancellor of the German Empire).

(Laura Acton Mighetti and Admiral Ferdinando Acton)

Of Ferdinando’s many children, the younger son, Amedeo, became (unsurprisingly) an admiral, and married the heiress of an old Neapolitan principality, Villa Santa Maria, so he was granted the use of the title himself, becoming the first Acton prince in 1926. The Princess’s older sister, Livia Giudice Caracciolo, had inherited her own Neapolitan principality, Leporano, though this title was not used by her husband, Alfredo Acton—yet another admiral—who was created Baron Acton in the Kingdom of Italy (1925). This was the year of his second appointment as Commander-in-Chief of the Italian Navy, having already held this post in 1919-21. He resigned the post once more in 1927 to become a Senator of the Kingdom of Italy, and died a few years later in 1934.

The Princess of Leporano came from a long line of Neapolitan aristocrats. The Caracciolo family had dominated politics in this region for centuries, claiming origins in the Byzantine nobility (as ‘Caracziolus’) who had implanted themselves in southern Italy by at least the 10th century. There were many, many branches (and the family will certainly have their own blog post), each with a duchy or a principality (or several). One branch added the name Giudice by marriage in 1722 to the heiress of Antonio del Giudice. This Neapolitan aristocrat is better known as the Prince of Cellamare, and was famous for his involvement in the ‘Cellamare Conspiracy’ as Spanish ambassador to France in 1718-19. Together with the Duke of Maine (Louis XIV’s illegitimate son), the plotters attempted to depose the Duke of Orléans and put Philip V of Spain in his place as Regent of France. Cellamare was arrested then sent home, and France soon declared war on Spain. The Prince returned to Naples where he set about expanding and beautifying his palazzo, one of the most prominent in Naples still today, the Palazzo Cellamare (often spelled Cellammare). This grand residence, on the boundary between the ancient city of Naples and its new suburb of Chiaia, rises high above the Via Chiaia, a very fashionable shopping street. It was built by one of the Carafa princes in the early 16th century, and following the death of the last member of that branch in 1689, it was taken over by the city, then sold to the Prince of Cellamare. In the 1720s, he built a new chapels and expanded the enclosed gardens that covered the hillside. In the later 18th century the palace was the home of the Prince of Francavilla (Michele Imperiali) who was a great art collector and host of Neapolitan high society. In the early 19th century, the palace hosted the collections of the royal family itself, who feared they might be looted by the French in the revolutionary era. A massive restoration project was started at the Palazzo Cellammare in 2021, notably re-opening a 1940s cinema, the ‘Metropolitan cine-theatre’, built in its underground foundations, and considered the largest cinema in Naples, with 3000 seats.

By the end of the 19th century, the head of the Giudice Carraciolo family was Prince of Cellamare, Prince of Villa Santa Maria, and Prince of Leporano—aside from Villa Santa Maria (in Abruzzo), these estates were based in Apulia (the ‘heel’ of the boot of Italy). Leporano, south of the city of Taranto, was originally elevated into a principality in 1624 for the Muscettola family (who also held the dukedom of Spezzano, in Calabria, the ‘toe’). The Castello Muscettola has origins in the 12th century, and was transformed from a defensive fortress to a residential palace in the 16th century, and passed to the Giudice Caracciolo family by marriage in the mid-19th century.

Princess Livia, ‘Lady Acton’, died in 1963, so her principality of Leporano and her duchy of Spezzano passed to her eldest son, though he had been granted the use of these titles by King Victor Emmanuel III as early as 1933. Fernando Amedeo Acton, 12th Prince of Leporano, also inherited his aunt’s parts of the Palazzo Cellammare in Naples in 1969. His younger brother Francesco was a naval commander in World War II and was given his own barony by the King in 1940. Also known as an art historian and museum director, he helped restore and rehabilitate several museums in postwar Naples and was for many years director of the Filangieri museum, in the Palazzo Cuomo, a famous collection of artworks, coins and books.

Today the 13th Prince of Leporano, Giovanni Acton, unmarried, lives in the Palazzo Cellammare in Naples, while the rural estates are tended to by his sister Eleonora (given use of the title Duchess of Spezzano by the ex-king Umberto II in 1979), and her son, Francesco Taccone (son of the Marchese di Sitizano). A quick search on the internet reveals two very beautifully designed websites: one for the Leporano estates in Apulia for the production and sales of traditional olives and olive oils; and one for another estate in Calabria, the Borgo di Cannavá (another former Giudice Caracciolo property), which hosts a yoga retreat centre.

The author Sir Harold Acton’s roots in Naples were thus extensive. But he was born and raised in Florence. His father Arthur, an illegitimate cousin of Alfredo and Amedeo, was a British architect and art dealer. In 1896 he was in Chicago helping to design the Italianate features of the new buildings of the Illinois Trust and Savings Bank, and soon after married the Bank’s president’s daughter, Hortense Mitchell. With her father’s money, they purchased the Villa La Pietra, in the hills just north of Florence, in 1907. It had been built in the Renaissance, and owned for many centuries by the Capponi family (one of Florence’s major dynasties). The Actons laid out a formal Baroque Italian garden, filling it with almost two hundred statues, and brought together a valuable collection of artworks in the house itself.

It was into this world that was born Harold, and his brother William, also known as one of the Bright Young Things in London, and specifically as a painter (but who died young in 1944). Harold was described in the 1930s as a ‘virile aesthete-dandy’, a close friend to Nancy Mitford and Evelyn Waugh, and one of the inspirations for the character of Anthony Blanche in Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited (published in 1945)—a character who is both very English and very foreign, and notably very Catholic, which Harold was. He was knighted in 1974 and died in 1994, leaving the Villa la Pietra to New York University. If ever a time machine is invented, this is definitely someone I would love to go back and enjoy a glass of sherry with.

(images Wikimedia Commons)