Shortly after his marriage to his first cousin, Princess Henrietta of England, in March 1661, Philippe de France, second son of Louis XIII and younger brother of Louis XIV, was given the Orléans apanage (for its earlier history, see Part I). Philippe had, as Gaston had before him, been known as Duke of Anjou, but just as a courtesy title. He was now formally Duke of Orléans, Duke of Chartres and Duke of Valois. Louis XIV restricted his brother’s access to the full wealth of the apanage however, by keeping the castles of Blois and Chambord for the Crown. Later Philippe’s apanage was augmented (at the time of his second marriage in 1671) with the Duchy of Nemours, and eventually (though many years later) he inherited significant properties from Gaston’s daughter, La Grande Mademoiselle, notably the Duchy of Montpensier and the Principality of Joinville—these latter two were not part of the apanage, but held as private property (ie, they could pass to a daughter or could be sold).

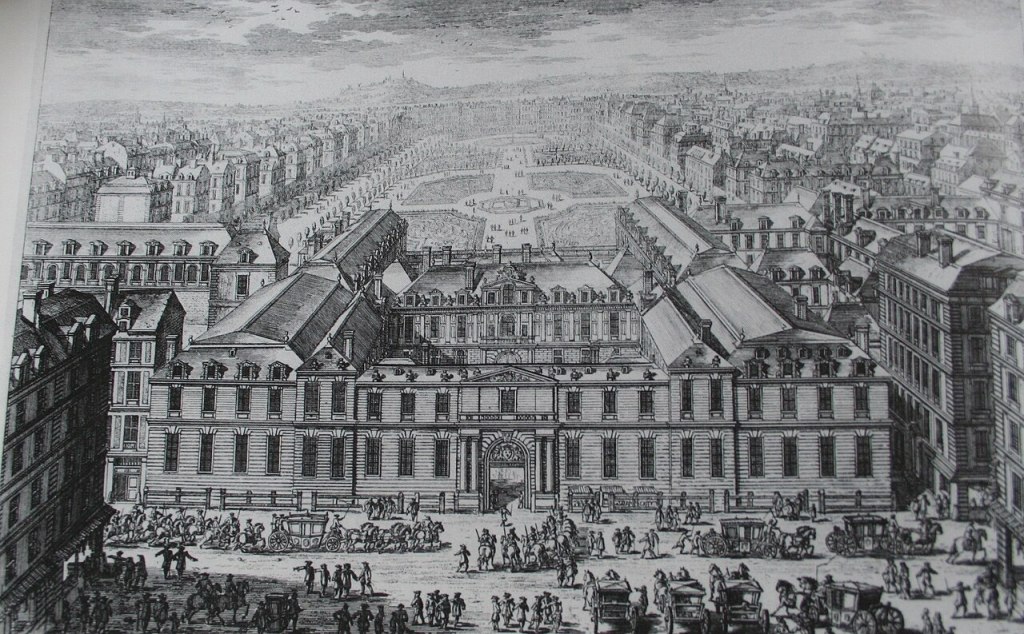

Philippe, Duke of Orléans, is different to his predecessors in that he had very little to do with the Orléannais. He did build the Orléans Canal, connecting the Loire to the Seine (via the Loiret) in the 1680s, but his life was lived almost exclusively at court or his preferred residences: the Palais-Royal in the heart of Paris, or the Château of Saint-Cloud on the road towards Versailles. The former was initially the grand palace built close to the Louvre by the First Minister of Louis XIII, Cardinal Richelieu, in 1629, so was known as the Palais Richelieu. After he died in 1642, it was taken over by Queen Anne and her two little boys, Louis XIV and Philippe, as a more comfortable residence compared to the old fortress of the Louvre. Renamed the Palais-Royal, it was given as a residence to Philippe after he married in 1661, then added more completely to his apanage in 1692—it thus remained part of the Orléans patrimony until the middle of the nineteenth century. Since the proclamation of the Third Republic it has housed various government institutions, notably the Council of State as well as the Ministry of Culture, which is appropriate since once wing still houses the Comédie-Française, which, in one form or another, has existed here since the Duke of Orléans installed the theatre troupe of Molière in the 1660s.

The Château of Saint-Cloud, initially built by the Gondi family of Florentine bankers on the outskirts of the city of Paris, it was purchased for Philippe by Cardinal Mazarin in 1658. It became his pride and joy, and the focus of his herculean patronage efforts in the 1670s-80s. Perched high above a bend in the river Seine, its chief glory was a grand waterfall called La Cascade, which is the only part of Saint-Cloud to remain visible today. Inside the château was a golden chamber where Philippe received guests, a gallery for Chinese porcelains and Japanese lacquers, and even a hall of mirrors, built several years before the more famous hall of that name at Versailles. Unfortunately, the Château of Saint-Cloud burned down in the turmoil at the end of the Franco-Prussian War in 1870.

If Philippe wanted to go further afield, unlike Gaston he did not go south to the Loire valley, but north to his Duchy of Valois and its chief château, Villers-Cotterêts. Built as a royal castle by François I in the 1530s on the site of an old hunting lodge, it was the site of a significant edict, in 1539, by which the King decreed that French, not Latin, would henceforth be the language of government and law. In 1661, it was given to Philippe as part of his apanage, and he spent much time here in the time of his first marriage to Henrietta of England, particularly at times when he left the court to protest against a decision made by his brother the King. Villers-Cotterêts remained in the Orléans family until the French Revolution when it was confiscated and given over for use by the French army, then in the nineteenth century was used as a home for the poor, and later a retreat for the elderly. This lasted until 2014 when the building was basically abandoned and was left to rot, until the French president established a Cité Internationale de la Langue Française—to commemorate the edict of 1539—and re-opened a renovated palace in 2023.

The Duke of Orléans had a huge apartment at Versailles as well, adjacent to the central core apartments of the King and the Queen. Known simply as ‘Monsieur’ as the brother of the King, Philippe was known as a prince who was loyal and fun, even frivolous and scandalous due to his fairly open sexual preference for men and his long-term relationship with the Chevalier de Lorraine. But he could be serious and reliable, offering support and counsel to his brother when needed on issues of court etiquette and proving himself as a commander on the battlefield, notably at the Battle of Cassel in Flanders where he defeated the Prince of Orange in 1677.

Philippe also did his duty in terms of the dynasty. He had a male partner for over thirty years, the Chevalier de Lorraine, but married twice, both for diplomatic reasons, and produced seven healthy children. His first wife was Henrietta, sister of the King of England, and his second was Elisabeth-Charlotte, daughter of the Elector Palatine of the Rhine. Naturally his focus was on having a son, to pass on the Orléans apanage. Philippe-Charles, Duke of Valois, was born in 1664, but died 2½ years later. Another Duke of Valois was born in 1673, Alexandre-Louis, followed by a second son, Philippe-Charles, called the Duke of Chartres, in 1674. Valois died in 1676, but Chartres survived, and as Philippe II, succeeded his father as Duke of Orléans in 1701.

**

A new House of Orléans was born—the first since the fifteenth century—and survived and thrived throughout the eighteenth century as the second royal family of France. Thanks to the work of Philippe I, a financial empire had been created that allowed them to be autonomous from the French Crown, a factor that irked their cousins Louis XV and Louis XVI.

From 1709, the Orléans princes added a new title: ‘First Prince of the Blood’. This was not given to Philippe II, since he already held a higher rank, ‘Grandson of France’, but to his son, Louis, born in 1703, and as his father had been, titled Duke of Chartres. This elevation in status meant that the Prince of Condé no longer held the prestigious title (and its pension) of ‘First Prince of the Blood’, and these two branches of the royal family, Bourbon-Orléans and Bourbon-Condé, would be rivals for the rest of the century. This rivalry was fiercest early on, when Philippe II was named Regent of France in 1715, in charge of the government during the minority of Louis XV (born in 1710), and Condé (known by his secondary title Duke of Bourbon) was given a seat on the Regency Council, but also looked after the King’s household as Grand Master of France. The two men were also brothers-in-law, both having married illegitimate daughters of Louis XIV. The Regency of the Duke of Orléans was a period of experimentation in government, mostly unsuccessful, though the King kept him on as First Minister when the Regency formally ended in 1722. When Orléans died in 1723, he was succeeded in this role by the Duke of Bourbon, who swiftly undid most of his rival’s policies, particularly in foreign policy.

For Orléans had not only solidified the King’s position abroad by arranging a marriage with the daughter of the King of Spain, he also ensured that the House of Orléans shared in this glory, by sending two of his own daughters to wed Spanish princes. Despite loathing his wife, Françoise-Marie de Bourbon, from the very start of their marriage (he called her ‘Madame Lucifer’), Philippe II had seven healthy children. Aside from the son and heir noted already, the eldest daughter ‘Mademoiselle’ (as the eldest unmarried daughter of the cadet line was always known) had been married to Louis XIV’s grandson, the Duke of Berry, while ‘Mlle de Valois’ was sent abroad to marry the Duke of Modena, before ‘Mlle de Montpensier’ and ‘Mlle de Beaujolais’ were sent off to Spain in 1723 to marry Crown Prince Luis and his brother Infante Felipe. The Crown Princess, Louise-Elisabeth, became Queen of Spain briefly in 1724, but due to her husband’s sudden death and her universally loathed behaviour, she (and her sister) were sent back to France, like unwanted packages. Once Louis XV began having children of his own, the children of the House of Orléans would return to their secondary position, as princes of the blood with the style of ‘Serene Highness’.

The new Duke of Orléans, Louis, was of a very different character to either his intellectual father or his vivacious grandfather. He seemed to have inherited some of his grandmother Madame de Montespan’s headstrong passions: as a young man he loved and he fought with vigour, not always forethought, and in middle age, he threw himself completely into a life of religious contemplation, retiring from the world of the court and becoming known as the ‘Hermit of Sainte-Geneviève’ (the abbey near the Latin quarter in Paris). Louis ‘the Pious’ had a short marriage to a German princess, Jeanne de Bade (Baden), which produced one child, a son, Louis-Philippe, Duke of Chartres (b. 1725).

Louis-Philippe, 4th Duke of Orléans, succeeded to this title in 1752. When he came of age in 1740, he had initially been proposed as a groom for Louis XV’s second daughter, Madame Henriette, and the teen-aged couple had even displayed real affection for each other; but it was decided that such a marriage would emphasise the Orléans cousins too much as potential heirs to the French throne and antagonise strained relations with Philip V of Spain. So the prince was married instead to another, more distant, Bourbon cousin, ‘Mlle de Conti’, in 1743, in an effort to heal the breach between the Orléans and Condé/Conti branches of the family. This marriage was not more successful than his grandparents’ had been, and they produced only two children, Louis-Philippe II, Duke of Chartres, and Bathilde. Orléans revealed his attachment to the ideas of the French Enlightenment through the education of these children, and in 1756 they were made examples of for the entire court by being inoculated for smallpox. Orléans was also an ally of his brother-in-law, the Prince of Conti, an influential member of the ‘loyal opposition’ to the King’s inclinations towards continued absolutism rather than the fresh political ideas of the era.

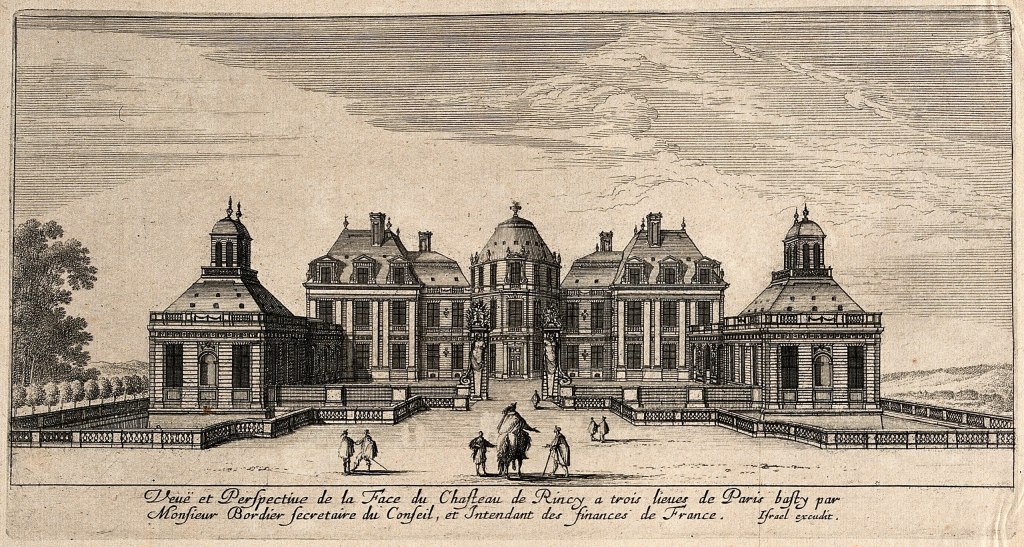

The 4th Duke of Orléans set out to expand the already vast Orléans empire, adding the county of Soissons to his apanage in 1751, and the nearby lordships of La Fère, Marle and Ham in Picardy. Like his great-grandfather, he increased his revenues by developing a waterway, the Ourcq Canal, to bring supplies and fresh water to Paris from his duchy of Valois; and developed the area around the Palais-Royal in Paris for commercial enterprise. His wife died in 1759, and the widowed Duke settled far from court at a large château he purchased in the countryside east of Paris, Le Raincy. This château had been built in the mid-seventeenth century and owned by the Princess Palatine (Anne de Gonzague) then her daughter the Princess of Condé. The Duke of Orléans now redesigned the château and developed its gardens in the newly fashionable English style.

Orléans moved here with his mistress, the widowed Marquise de Montesson. They forged a committed relationship and the King agreed to their marriage in 1773, as long as it remained secret and she was not given any rights or titles. The Duke was mocked by members of high society, who quipped that “unable to make Madame de Montesson a Duchess of Orléans, he made himself Monsieur de Montesson”. The new couple acquired yet another château, Sainte-Assise, southeast of Paris on the road to Fontainebleau. Here the Duke put on great entertainments for his guests, with plays written and acted by the Marquise. Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette refused to visit what they saw as a shocking set up, which further distanced Orléans from his support of the Crown. This château has survived, modified, passing through many hands until it was owned by the princes of Beauvau, but since the 1920s property of a radio broadcasting company.

The Duke of Orléans was already annoyed with the royal family since he had tried to negotiate a marriage for his son with Princess Kunigunde of Poland in 1769, but was blocked by the King who thought that Chartres was not of sufficient rank to marry the daughter of a king. The Duke arranged instead a wedding to the daughter of the Duke of Penthièvre, a Bourbon, but from an illegitimate branch. Members of the court mocked him again, scorning this marriage as a mésalliance. A convincing factor was of course the bride’s vast fortune: a dowry worth about four million livres in real estate, and some of the finest châteaux of the Loire valley.

The union of two of the grandest fortunes in France, Orléans and Penthièvre, in 1769, ensured that the family could act independently of the Crown, and both the Duke of Orléans and the Duke of Chartres shocked the court by signing a letter of protest against the King’s plans to dismiss the parlements of France in 1771—along with several other princes of the blood, they were exiled from court. The Palais-Royal became a focal point for political discontent against the troubled regime of Louis XV.

As a new reign began in 1774, the Duke of Orléans retreated to the Château de Sainte-Assise with his wife, Madame de Montesson. The Duke of Chartres, named formally Louis-Philippe II but referred to generally as Philippe, was also socially isolated, despite his early friendship with Marie-Antoinette and the bright young things at court. Like them, he too accumulated debts through lavish living and grand patronage of artists and architects. One of his early projects was the pleasure gardens at Monceau, on the northern edge of Paris. This ‘fantasy park’ brought together elements from around the world: a Chinese pagoda, an Egyptian pyramid, a Roman colonnade, a Dutch windmill… The Duke’s servants walked around the park dressed in Chinese costume or as animals. He later added a large rotunda, the Pavillon de Chartres, with offices on the ground floor and an apartment above for himself and his mistresses.

Meanwhile Chartres was raising two families. With his wife Marie-Adélaïde (the former ‘Mlle de Penthièvre’), he had a son, Louis-Philippe III, Duke of Valois, in 1773, followed by another, Antoine-Philippe, Duke of Montpensier, in 1775. These boys were followed by twin girls in 1777, Mlle d’Orléans and Mlle de Chartres, and then another son, Louis-Charles, Count of Beaujolais, in 1779. The Duke was also raising two foundling daughters with his mistress, the Comtesse de Genlis, a niece of Madame de Montesson who had been appointed as a lady-in-waiting to his wife. The more well-known of these daughters, Paméla, was officially an orphan, but may have been Chartres’ child. All the children were raised together, with Madame de Genlis as their governess. She already had a reputation as an educationalist; her aim was to mould the young princes with values of humility and public service. They read Voltaire and Rousseau, and she encouraged them to gain confidence and poise through theatre—she even published an educational tract on this theme, amongst her other works on the education of princes and of women.

Madame de Genlis’ focus on educating young women had the most impact on Mlle d’Orléans, Adélaïde, who became a respected intellect as an adult; she never married and remained a constant figure at the side of her brother Louis-Philippe well into the nineteenth century. Paméla went abroad during the Revolution and married Lord Edward Fitzgerald, a leader of the Irish Revolt of 1798, during which he was arrested and died in prison.

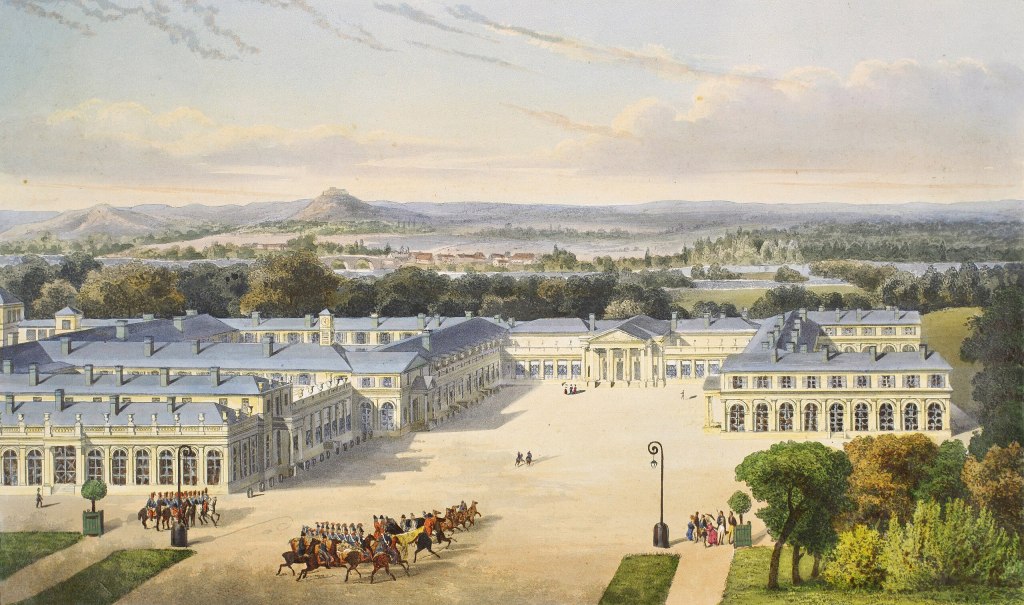

The Duke and Duchess of Chartres lived mainly at the Palais-Royal in Paris and sometimes at their suburban residence the Château of Saint-Cloud. But Saint-Cloud had been neglected, and just before he died in 1785, the old Duke of Orléans sold it to the Crown. The new 5th Duke of Orléans was able to use these funds therefore to focus his attentions on expanding the gardens at his father’s favoured country retreat, the Château of Le Raincy. Already the most English of the Bourbon princes, Philippe d’Orléans refashioned the gardens along the latest English styles. He even built a small café for visitors in which the waiters spoke English. He also had a new English mistress, the well-known socialite Grace Elliott. Ever the anglophile, the prince spent a good deal of time in London, with a house on Portland Place, living incognito as the ‘Count of Joinville’. He desired nothing more than to live as a ‘Milord Anglais’, investing in business, betting on horses at Newmarket, and gambling with his old friend, and fellow liberal, Charles James Fox.

With two families and expensive building projects, Orléans thus needed employment. As part of his marriage arrangements with the daughter of the Duke of Penthièvre, Admiral of France, it was understood that Philippe would embark on a naval career and ultimately succeed his father-in-law in this prestigious post. He had begun service in the navy in 1772, served in a few campaigns, and by 1778 was a junior admiral. But that summer he made a crucial command error during the battle of Ouessant (‘Ushant’ in English) off the coast of Brittany that allowed the British navy to escape. He was not given another command, further alienating him from Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette.

By the mid-1780s, Orléans had a significant political faction of his own, supporting opponents of the Crown known as the ‘Patriot Party’. In 1784, he allowed a banned play, ‘The Marriage of Figaro’ to be put on at the Comédie française, the theatre supported by him at the Palais-Royal. He took part in the Assembly of the Notables in 1787, where he protested against the Crown’s fiscal proposals and called for an Estates General. The King clashed violently with his cousin the Duke, publicly, in Parlement: when the Duke questioned the legality of a new law being presented, the King shouted ‘It is legal because I wish it!’ Orléans was once again forbidden from appearing in Parlement, and two of his supporters were arrested. In the winter of 1788-89, the Palais-Royal hummed with activity, printing pamphlets to agitate the public.

As Revolution broke out in Paris in the summer of 1789, the Palais-Royal remained the nerve centre for popular radicalism, where cries for reform became ever louder. The Estates General proclaimed itself a National Assembly on 20 June, and most of the clergy defied the King by joining it on 25 June, followed the next day by nearly fifty nobles—led by Philippe, Duke of Orléans, First Prince of the Blood. He was soon asked to preside over that body, but refused. He also rejected—at least publicly—calls to name him Lieutenant-General of the Kingdom or regent for the Dauphin, or even king himself. Orléans at first tried to act as a mediator between the Assembly and his cousin the King, but was pushed away by the court. The King sent him as a diplomatic envoy to Great Britain, where he tried to use his popularity in high society in London to forge a career as international diplomat. By mid-1790 his popularity in Paris was fading as the revolution radicalised and anyone with connections to the Old Regime, no matter how liberal their personal politics, became suspect. Many found it suspicious that much of his private fortune had been moved into British banks and investments.

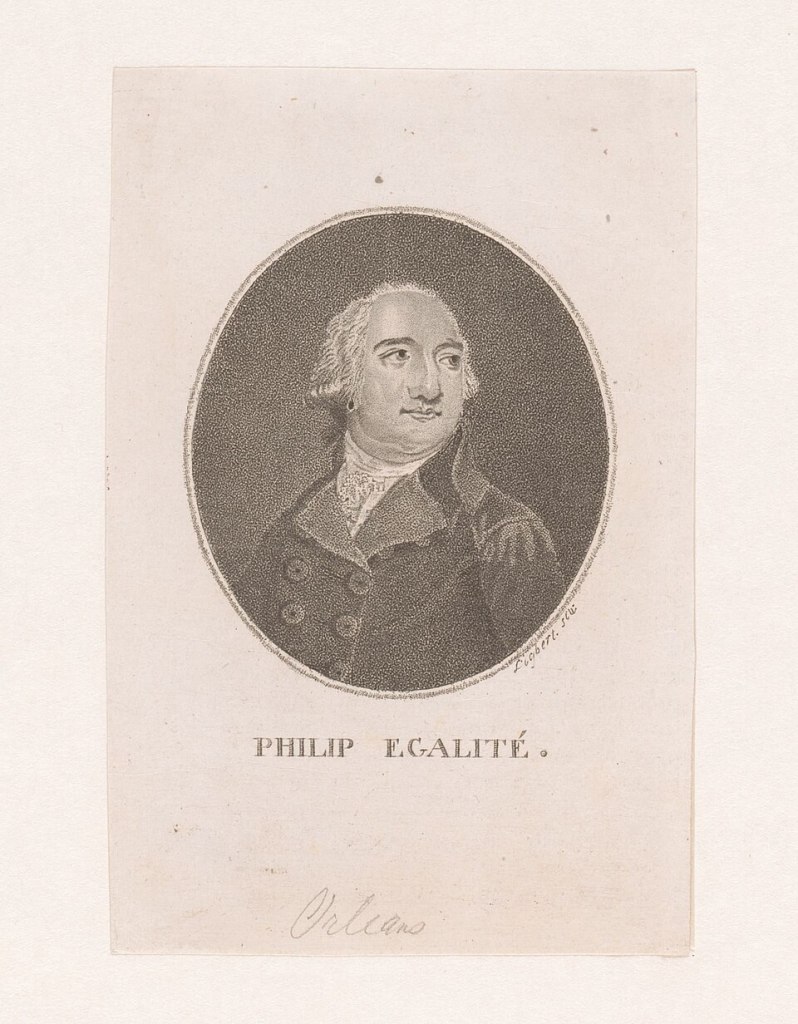

Nevertheless, the Duke of Orléans continued to demonstrate his devotion to the Revolution. He joined the Jacobin Club, and after the King’s attempted flight from France in June 1791, formally asserted his loyalty and again dismissed ideas of making him regent or king. He even changed his name: after the proclamation of the Republic in September 1792 and his election as a deputy to the Convention, he took the name ‘Philippe Égalité’. His eldest son Louis-Philippe eagerly followed his father’s lead; he joined the Army of the North in the summer of 1791, and swiftly gained glory, notably at one of the first victories of the revolutionary armies at Quiévrain, April 1792. In January 1793, Égalité made his most powerful mark on the history of France by voting for the death of Louis XVI, and opposing any efforts to amend the sentence to exile or life imprisonment.

But only a few months later, the defection of General Dumouriez into Austrian service, prompted the start of the Terror. Crucially, Dumouriez had convinced Égalité’s son, the former Duke of Chartres, to go with him. This defection made it clear to the revolutionary government that no one of royal blood could be trusted. On 1 April 1793, a decree was passed in the National Convention that condemned to death anyone with connections to counter-revolution. Philippe Égalité had voted in favour, yet just seven days later, he himself was arrested and taken to prison. He was put on trial on 6 November and guillotined the same day.

The new (if nominal) Duke of Orléans, Louis-Philippe III, age 20, headed to Switzerland where he moved from place to place, teaching classes to earn much-needed money, then began several years of far-reaching—and rather extraordinary for a Bourbon prince—peregrinations in Europe and North America. After a year in Scandinavia in 1795, he travelled to the United States, settling at first in Philadelphia. Joined by his brothers Montpensier and Beaujolais, he spent time in New York City and Boston, and travelled as far as Tennessee and Maine. In early 1798, hearing that their mother had been deported from France, the brothers travelled south to New Orleans, the city named for their great-great-grandfather, the Regent Orléans, hoping to return to Europe. After a year, they finally made their way back and settled in Twickenham, in the western suburbs of London. Here they watched as the Napoleonic wars unfolded, maintained by the British government as potential political or diplomatic pawns.

In 1809 the Duke of Orléans journeyed to Sicily where he met and married his cousin, Maria Amalia, daughter of King Ferdinand IV. The marriage had been fiercely opposed by Queen Maria Carolina—the sister of Marie-Antoinette—who harboured great anger against the regicide Philippe Égalité, the groom’s late father. The new couple remained in Palermo, in a residence near the Royal Palace, the ‘Palazzo Orléans’, where three of their children were born before they finally returned to France in 1814. The Palazzo Orléans would remain an important Orléans residence until it was seized by the Italian state in 1940—today it serves as the seat of the president and the Regional Council of Sicily.

Sadly, neither of the Duke’s brothers survived the revolutionary period. Both Montpensier and Beaujolais had been kept in prison in Marseilles for several years after their father’s arrest, and both suffered long-term damage to their health. After their adventures in America, Montpensier’s health worsened and he died near Windsor in 1807; while Beaujolais, who had joined the British Navy in 1804, tried to improve his health by visiting the Mediterranean, but he too died, on Malta, in 1808. The Dowager Duchess of Orléans also survived the Revolution. Despite her disinterest in revolutionary politics, following her husband’s execution, the ‘Veuve Égalité’ had been brought back to Paris in late 1793 and imprisoned in the Luxembourg Palace; here she met and fell in love with a disgraced Girondin deputy, Jacques-Marie Rouzet, who later obtained Marie-Adélaïde’s freedom and lived with her in Paris until both were exiled in 1797. They resided first in Spain, then in 1809 joined the small Orléans court in Palermo, then returned to France in June 1814.

**

At the Restoration of the French Monarchy in Spring 1814, Louis XVIII made every effort to reconcile the two branches of the royal family. The 6th Duke of Orléans, Louis-Philippe III, returned to France from Sicily with his wife and children. At first an eager supporter of his royal cousin’s regime, when Napoleon returned from Elba in March 1815, Orléans did not accompany the King and his court to Ghent, and instead established connections with the Bonapartist government. Thus the hereditary mistrust of the two branches was rekindled and continued to fester in the second Bourbon Restoration through minor but very public humiliations, like denying Orléans the use of the royal box at the Opera. Although an avowed liberal, Orléans was strongly attached to etiquette and hated being slighted socially, for example being treated as a ‘Serene Highness’ when, in comparison, visiting foreign princes from junior ruling houses like Bavaria and Saxony were now ‘Royal Highness’. When Charles X took the throne in 1825, he tried to balance this by decreeing that all princes of the blood would be Royal Highnesses.

The Orléans family residence was re-established at the Palais-Royal in the centre of Paris, where Duchess Marie-Amélie was formally hostess. She had a relatively reserved personality, and society looked instead to the Duke’s sister, Adélaïde, ‘Mademoiselle’, as the real political hostess. She ran a salon attended by Parisian liberals and clashed with the senior women of the royal family. The Duke’s mother, the Dowager Duchess Marie-Adélaïde set about asserting her possession of the numerous properties she had inherited from her father, the Duke of Penthièvre. One of the major châteaux added to the Orléans holdings at this time was Amboise, in the Loire valley. Amboise, in Touraine, had been a royal property since Charles VII confiscated it from the powerful Amboise family in 1434. It had been part of the apanage of Gaston, Duke of Orléans, between the 1620s and 1660s, but was otherwise maintained as a royal, not ducal, property—associated probably the most with King Francis I and his invited Italian master, Leonardo da Vinci (who lived in the smaller château next door 1516-19). Gifted by Louis XV to his First Minister the Duke of Choiseul, and after his death purchased by the Duke of Penthièvre, it thus entered the portfolio of the dukes of Orléans. In the nineteenth century the family set out to restore it to its former glory, and the family foundation, the Fondation Saint-Louis continues to do so today.

Besides the Dowager Duchess’s recouping of properties like Amboise, but also the Norman estates of Eu and Aumale, her most enduring contribution to the House of Orléans was the construction of a new site, the Royal Chapel of Saint-Louis, built at Dreux from 1816, a fantastic example of Neo-Gothic architecture, about an hour west of Paris. It became the necropolis for the Orléans family and a centre for royal ritual and memory—which it remains to this day.

The Orléans family also acquired a new country residence: the Château of Neuilly, in the western suburbs of Paris. Neuilly had been built in the 1750s and passed through various hands until it was bought by Marshal Joachim Murat in 1804 who expanded it then gave it to Napoleon’s sister Pauline in 1808. In 1819, the Duke of Orléans acquired the château and its extensive parklands for his summer residence. It remained a centre of Orléanism for the next three decades until it burned down in 1848 and its estate auctioned off. Part of it survives today as a convent.

Further afield Mademoiselle purchased a château of her own far to the south in rural Auvergne, Randan, which she rebuilt as a neo-gothic fantasy. This castle had been built by local lords in the thirteenth century who took the name ‘Château-Randan’, then passed to the Viscounts of Polignac, another Auvergnat family in the sixteenth century who rebuilt it in a Renaissance style. It passed to the La Rochefoucauld and Bauffremont families, under whom Randan was erected into a curious dukedom for mother and daughter (for whom there will be a future blog post), before it passed through several other ducal families: Foix-Candale, Caumont, Durfort and Choiseul. An heir to the later sold it to Mademoiselle in 1821. The Orléans family held on to the property until the 1920s when a terrible fire destroyed most of the building. An heiress took it to the Huarte family from Spain until the regional government purchased the ruins in 1999.

Meanwhile, the Duke of Orléans’ personal fortune had continued to grow. Already one of the richest men in France, he inherited the vast estates of his mother in 1821. Then in 1829, the last Prince of Condé made a will naming Orléans’ fifth son Henri his universal heir, bringing an even larger fortune into the collective arms of the House of Bourbon-Orléans. This included in particular the spectacular domain of Chantilly, north of Paris. An ancient lordship of the Montmorency family, Chantilly had been turned into a princely seat by the princes of Condé in the eighteenth century, famous notably for its stables built on a royal scale. Henri d’Orléans, created Duke of Aumale by his father, rebuilt the château entirely in the 1870s in a deliberately historicist style. When he died in 1897, Aumale donated the château and its estates to the Institut de France, which still owns it today. It maintains some of the finest elements of the Condé-Orléans art collections and a great library—a treasure-trove to historians of Bourbon history.

In Paris, the Palais-Royal continued to buzz as a centre of Orléanism. It was the setting for a huge party in May 1830, just as a political crisis was brewing that would bring down the senior branch of the Bourbons just over a month later. Orléans made headlines by celebrating in style the visit of his brother-in-law, the King of the Two Sicilies. There were 3,000 guests, but there were also crowds shouting against the King’s new ultra-royalist ministry. When political events spiralled out of control for Charles X in July, the King attempted to preserve the throne by appointing the Duke of Orléans—his cousin and old friend from their far-off youth at Versailles, but by now on far ends of the political spectrum—as Lieutenant-General of the Kingdom, and hopefully as regent for his grandson, the Duke of Bordeaux. Louis-Philippe hesitated between accepting these proposals, or suggestions that he accept the French crown himself. His family was divided: his sister Adélaïde urged him to take the throne, against the views of his more conservative wife Marie-Amélie. Orléans himself was at the Château of Le Raincy, while the two women were both at Neuilly—so when the delegation from the provisional government came there, Adélaïde accepted the crown on her brother’s behalf.

Back in Paris, Louis-Philippe was unsure what to do following this ‘July Revolution’. He was very popular, as a moderate option between ultra-royalism, militant Bonapartism or radical republicanism. On 8 August the Chamber of Peers invited him not to be regent, but king, and he accepted. He chose the regnal name Louis-Philippe I, and adopted the title ‘King of the French’ (not ‘of France’) indicating that his throne came from popular sovereignty, not divine will or ancient conquest. He was officially proclaimed king by the French legislature at the Palais Bourbon on 9 August 1830. He was escorted during the ceremony by two of his sons, the dukes of Chartres and Nemours. A few days later, Chartres was re-branded as Duke of Orléans and ‘Prince Royal’—not Dauphin, another sign of the new approach for this ‘July Monarchy’.

**

The rest of the story of King Louis-Philippe is the history of the French monarchy rather than the dukes of Orléans—though it should be noted that several more conservative foreign royal families continued to refer to him as the Duke of Orléans, seeing him as no more than a usurper—so we should move on to his son and anticipated successor.

Prince Ferdinand-Philippe, born in Palermo in 1810, had been named for his grandfathers, King Ferdinand of Naples and Philippe d’Orléans. During the Restoration he had been educated in Paris and steered towards a military career. Once he became Duke of Orléans in 1830, Ferdinand swiftly became a quite popular prince, helping to put down a revolt of silk workers in Lyon without violence and visiting cholera patients in Paris. He earned military glory through his service in military ventures in Belgium (1831-32) and in three campaigns in the French conquest of Algeria (1835-36, 1839 and 1840). He was seen as a great hope for the future of Orléanism in France and therefore needed to marry and produce an heir. In 1836, Ferdinand went on tour to the capitals of Europe—Brussels, Berlin, Vienna—but did not find a suitable Catholic bride. The search was widened to include Protestant princesses with links to the ruling houses of Denmark or Prussia. Here the Duke of Orléans finally found his match, Helene of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, a niece of the King of Prussia. They were married in May 1837, in a civil ceremony at Fontainebleau since the Archbishop of Paris refused to preside over a wedding to a Protestant in Notre Dame Cathedral. They soon had two sons, Philippe and Robert, and set themselves up in the Tuileries Palace, where the prince established a large collection of medieval art and East Asian porcelains.

Just as things were looking rosy for the next generation of the House of Orléans, in July 1842, the Duke was injured in a carriage accident on the road to Neuilly and died several hours later. All of France went into mourning, and eventually several grand memorial statues were erected to his memory. Perhaps the most touching is the memorial on his tomb at the Saint-Louis Chapel at Dreux, finished only when his widow died in 1858; as a Protestant, Hélène could not be interred within the chapel, so her sarcophagus sits just outside, and her outstretched arm reaches through the wall for the hand of her beloved.

There was already hope for the next generation, however. After 1842, the Duke of Orléans’ son, Philippe, became the ‘Prince Royal’, as heir to his grandfather. He was given the courtesy title ‘Count of Paris’, a deliberate re-assertion of the ancientness of the dynasty, one of the very first titles used by Hugh Capet before his rise to the French throne in 987. His younger brother, Robert, was given the title Duke of Chartres. There were also numerous other dynastic titles regularly seen in the House of Orléans, now in use for the King’s numerous sons and grandsons (Nemours, Joinville, Aumale, Montpensier, Penthièvre), and new ones added from the succession of the Prince of Condé (Guise, Alençon or Condé itself). Louis, Duke of Nemours would become head of the family after their father’s death in 1850 (since his nephews were children), while Henri, Duke of Aumale later became its intellectual head, as a historian and political writer. Antoine, Duke of Montpensier married a Spanish infanta and established a separate branch that meddled in internal affairs in Spain, and remains a part of the extended Spanish royal family today.

The Orléans monarchy fell in 1848. There would be no more formal dukes of Orléans, but the title was used again, as a ‘courtesy’ by later members of the family.

The previous Duke of Orléans’ son, Philippe, Count of Paris, died in 1894, he was succeeded as head of the royal family in exile by his son, Philippe, who took the title ‘Philip VIII’. Born in Twickenham in 1860, he returned to France with his family in 1871 at the fall of the Second Empire, but was exiled again by the Third Republic in 1886. In 1880, his father gave him the title ‘Duke of Orléans’, and sent him to complete his education at Sandhurst—he then served as a staff officer to Lord Roberts, Commander-in-Chief of the British Army in India. In 1890 he came of age, and demanded he be allowed to fulfil his required military service like any young Frenchman. Instead, French officials arrested him and imprisoned him in the Conciergerie in Paris. But here he was well housed and well fed; he received high-ranking visitors and even carried on an affair with a Parisian dancer. He was soon pardoned and evicted from France, mocked by the French press for being such a pampered prisoner.

While the family had resided in Paris in the 1870s, they lived at the Hôtel de Galliera in the fashionable faubourg Saint-Germain. This enormous hôtel particulier was built for the princes of Monaco in the 1720s and called the Hôtel de Matignon (the princes’ former surname before they adopted Grimaldi). Confiscated during the Revolution it was later given the Crown to the Orléans family, who eventually sold it to the Duke of Galliera (like the Grimaldi, from a family of Genoese bankers), whose widow then generously opened it up for the Count of Paris and his family (since they no longer owned the Palais-Royal). After her death it became the Embassy of Austria-Hungary, then was acquired by the French government for use as a residence of the head of government. Renamed Hôtel de Matignon, it still houses the Prime Minister of France.

In 1886, when the news came that the Orléans family had to leave France, they were spending the summer at their preferred country residence, the Château of Eu. Like Chantilly and Amboise, Eu is one of the finest remainders of the glories of France’s country houses. It was built in the 1570s by the Duke of Guise on the site of an ancient fortress—watching over this area of the Norman coast since the tenth century. The Guise family passed it in 1661 to La Grande Mademoiselle (Gaston d’Orléans’ daughter, seen above), who was forced by Louis XIV to give it to his illegitimate son, the Duke of Maine. From Maine’s heirs it passed to the Duke of Penthièvre and thus back into the House of Orléans, along with its vast forests—a significant source of revenue for the family. It was the favoured country retreat of Louis-Philippe during the July Monarchy, and was where he received Queen Victoria and her family in a famous meeting of the monarchs that established an entente cordiale in 1845. From 1905 to 1940, it was the residence of one branch of the Orléans family who were also (by marriage) the claimants to the imperial throne of Brazil (Orléans-Bragance). Sold by their heirs in 1964 to the town of Eu, the château now houses a very grand Musée Louis-Philippe. Interestingly, some of the estate is still owned by the last Duke of Orléans (below) and his cousin.

Over the next two decades, the exiled Duke of Orléans became an explorer, notably in the Arctic, discovering new parts of northeast Greenland (‘Duke of Orléans Land’ and nearby ‘Cape Philippe’). Boatloads of stuffed wildlife were brought back to England and to his new residence in Worcestershire, Wood Norton. He was elected to the Royal Geographic Society in 1893. Just before the First World War, however, he moved to Belgium, to a residence dubbed the ‘Manoir d’Anjou’ at Putdaël, near Brussels. Huge dioramas of natural scenes had been created at his museum in Wood Norton, which eventually were donated to the National History Museum in Paris (the ‘Gallerie du duc d’Orléans’—built in 1928, torn down in 1959). Politically he had tried to keep Orléanism alive, but distanced himself from the far right wing monarchist party, Action française. The Duke of Orléans died in 1926 in the Orléans Palace in Palermo, Sicily. In 1896, he had married Archduchess Maria Dorothea of Austria, but they soon separated and had no children.

The headship of the House of Orléans passed to a cousin, whose son ultimately took over as Henri, Count of Paris. His second son Prince François was killed in Algeria in 1960 and was posthumously given the title of Duke of Orléans. A few years later, in 1969, the title was revived for the fourth son, Prince Jacques. Born in 1941 in Rabat in the French Protectorate of Morrocco, Jacques was the younger of a pair of twins. Michel, the older brother, was moved to a lower position in the order of succession by their father when he married a woman of unequal rank. Jacques married the daughter of a French duke, Gersende de Sabran-Pontevès, which was deemed appropriate—and the reversal of their birth order was confirmed by later heads of the family. It was said that the ducal title of Orléans was given as a snub to his twin (titled merely Count of Evreux), and in consequence, Jacques’ sons would be given higher ranking titles: Duke of Chartres (b. 1972) and Duke of Aumale (b. 1974). Prince Jacques also has a daughter who married the second son of the Duke of Mouchy (a Noailles).

In the 1990s, the Duke of Orléans led his siblings in a revolt against their father, in an attempt to block his sales of some of the family properties (and to raid the private fortune of his wife, their mother). Orléans would publish a tell-all book about it in 1999. At the time, the family still owned property worth about 15 million euros, including art and jewels, the Château of Amboise, and the domain of Dreux with the family necropolis. Other items had been sold long before, notably the Manoir d’Anjou in Belgium and the Palais d’Orléans in Sicily in the 1940s.

The current Duke of Orléans’ children are considered by Orléanist monarchists to hold the rank of ‘first prince of the blood’. Somewhat confusingly, those who support the Legitimists in case of a restoration of the French throne (the House of Anjou in Spain) consider instead that the head of this branch of the family, Prince Jean, is not the Count of Paris, but in fact the 13th Duke of Orléans, by right of primogeniture established by Louis XIV for his brother Philippe all the way back in 1661.

(images Wikimedia Commons)

One thought on “The Dukes of Orléans: A ‘Spare’ Title for France’s Second Sons (Part II)”