The new Grand Duchess of Luxembourg, born Countess Stéphanie de Lannoy, comes from an old noble family from the Low Countries. The House of Lannoy is one of the most distinguished noble houses in Belgium, yet nether of the two princely titles they held at different parts of their history—Sulmona and Rheina-Wolbeck—were located in Belgium. Nor in fact is the village of Lannoy itself in … any more.

The name Lannoy, as the seventeenth-century royal genealogist Père Anselme pointed out, is pretty common, and the commonness of the name goes back to its probable meaning, l’aune or the alder tree. There was, for example, a castle and lordship of Lannoy in eastern Lorraine in the Middle Ages; and in the seventeenth century, a Lannoy family came to great prominence at the French court, then died out. Charles, Comte de Lannoy (or sometimes Lannois) was the King’s Premier Maître d’Hôtel in the 1640s, and Lord of Brunoy, a seigneurie on the banks of the Seine southeast of Paris which he left to his daughter, Anne-Elizabeth, who married the Duke of Elbeuf, one of the subjects of my doctoral research—Brunoy was later given to the Count of Provence, younger brother of Louis XVI, and erected into a duchy-peerage, so was again central to my own research on this prince. But neither of these Lannoy families connect directly with those of Belgium, There is also a claim—maybe true, maybe not—that a younger son of one of the Belgian Lannoys became a Protestant during the Reformation and his descendants left for America in the 1620s where they spelled their name De Lano or Delano, and became one of the leading families of Boston, and ultimately gave their surname to Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

The village of Lannoy we are concerned with here is in French Flanders. It is now part of the wider suburban sprawl of the city of Lille in France, but very close to the border with Belgium. Lille was once one of the major towns of the County of Flanders, as part of the Spanish Netherlands, but when it was captured by the French in the late 1660s, it took with it the village of Lannoy. By this point, the Lannoy family were no longer proprietors of the fief, it having passed out of the family at the end of the fifteenth century. There had been a castle there, of which little remains, but the Lannoy family did retain their very distinctive coat of arms, three green lions, crowned, on a silver field.

The Lannoy family were based in French Flanders and in Hainaut, the county immediately east to the east (also divided today between France and Belgium). This is a francophone area, but they also held lands further north in Flemish speaking areas around the regional capital, Brussels, and one branch expanded further east and held the lordship of Clervaux in Luxembourg, where German (or a German dialect) was more common. As noted above, their princely titles were even more far flung, with Sulmona being in the Kingdom of Naples and Rheina-Wolbeck being in northwest Germany, near the city of Münster.

The first members of the family who came to real prominence were three brothers from the cadet line of Santes and Molenbaix (lordships located on either side of Lille), Hugo, Gilbert and Baldwin. All three held senior positions at the court of the dukes of Burgundy in the early fifteenth century. The dukes of Burgundy were at their height as princes at this point, and often based their court nearby at Lille. Hugo and Gilbert were both diplomats and soldiers for hire, travelling to the Holy Land, Muscovy, Spain and Poland. Both fought at Agincourt against the English. As part of the peace process that followed, Hugo arranged a marriage between the Countess of Holland and the Duke of Gloucester (brother of Henry V), while Gilbert was sent by Henry V to Syria and Egypt in 1421 to sound out possibilities of re-establishing a Christian Kingdom in Jerusalem. He published accounts of his travels in the Middle East, Poland and Russia, and also wrote a book, Advice for a Young Prince, in 1440, for the young Prince Charles of Burgundy, later Duke Charles the Rash (clearly not taking Gilbert de Lannoy’s advice).

The youngest brother, Baldwin, was also an ambassador from Burgundy to the court of Henry V, and served as Governor of Lille for fifty years (1424-74). All three were founding members of the Order of the Golden Fleece when it was instituted by Duke Philip the Good in 1430—its first chapter met in Lille. Baldwin celebrated the event by having his portrait painted by Jan Van Eyck.

In the next generation, the head of the senior branch, still based at Lannoy itself, Jean II, was also a knight of the Order of the Golden Fleece (and also depicted in their distinctive red robes in a book of their statutes compiled in 1473). In all, fifteen members of the House of Lannoy would receive this honour. His father Jean I had been killed at Agincourt, so Jean was lord from a young age. He was nephew of Antoine de Croÿ, one of Burgundy’s leading courtiers (and of Agnès de Croÿ, mistress of the Duke), and by 1448 was appointed Stadtholder (or governor) of Holland and Zealand, adding Walloon Flanders (the French-speaking parts of the county around Lille and Douai) in 1459. At this point he befriended the young Dauphin of France, Louis, who spend several years in Burgundy in exile, then helped this prince reclaim his throne as Louis XI in 1461. But this shift in loyalty angered the Duke of Burgundy, Charles the Rash, so Lannoy lost his posts in the Low Countries in 1463, and by 1468 was in open conflict with his former lord and went into exile in France. He returned to service in Burgundy when it was taken over by Emperor Maximilian (married to Mary of Burgundy, Duke Charles’s heiress), serving as his chamberlain and ambassador—notably in 1482 to arrange peace with his old friend Louis XI.

When Jean de Lannoy died in 1493, his lands were divided up by his daughters, and Lannoy itself passed out of the family. His brother Antoine founded a line at Maingoval (today spelled Mingoval) in Artois. It was his grandson Charles who was the most famous member of the House of Lannoy and its first prince. His early career was spent as a soldier in the service of Emperor Maximilian’s son, Philip the Handsome, husband to Juana, heiress of the kingdoms of Castile and Aragon. In 1515, Charles de Lannoy was appointed First Equerry and a member of the council of their son Charles, Duke of Burgundy, who soon became king of Castile and Aragon as Carlos I (and Lannoy’s title became Caballerizo mayor), and after 1519, Holy Roman Emperor as Charles V. in 1511, Charles de Lannoy purchased a sizeable castle in Brabant to be closer to the court in Brussels, Hof ter Ham, in the town of Steen-Ockerzeel, northeast of Brussels. It was a medieval castle rebuilt in a more modern style with a much grander moat in the 1490s by Philippe Hinckaert, a leading courtier. The Lannoy family sold it in 1577, and it would be held by various Belgian families until 1929 when it was leased to the exiled Emperess Zita of Austria-Hungary who raised her large brood of Habsburg archdukes and archduchesses here until 1940 when they fled to Canada in the face of the Nazi invasion. Badly damaged in the war, it has been beautifully restored.

In the 1520s, the Emperor-King fixed his eyes on the Italian peninsula. He wished to secure his grandfather’s succession in the Kingdom of Naples, but also to wrest control of the Duchy of Milan from the French who had taken it in 1515. Lannoy was at first sent to Naples to govern as Viceroy, 1522-23. In 1523 he was brought north to Lombardy and given command of Charles V’s armies: he defeated the French first at Sessia in 1524, then decisively at Pavia in 1525—we have seen in 2025 several commemorations of that epic battle between Francis I and Charles V, resulting in the King of France’s capture and utter humiliation. It was Charles de Lannoy in fact who was charged with taking the captive King Francis to Madrid, then escorting him to the frontier with France a year later to exchange him for his young sons as hostages. As a reward, in 1526, Charles de Lannoy (or Don Carlos de Lannoi) was created a count of the Empire (a benefit accrued to his family as a whole), and was given the County of Asti in Lombardy (recently conquered from the French) and the Principality of Sulmona in the Abruzzo, the northernmost province of the Kingdom of Naples on the Adriatic coast (and also given the fief of Ortona, sometimes spelled Ortona a Mare, as the chief port of Abruzzo). He was given the rank of a Grandee of Spain. Charles de Lannoy died in Gaeta, one of the chief fortress cities of Naples, in 1527.

Sulmona the city is famous as the birthplace of the poet Ovid. Today it is more well known as the home of confetti, the brightly coloured sugared almond candies. Most of the medieval city was destroyed in an earthquake in 1706, so today’s appearance is almost completely baroque. The Lannoy family did not reside here in a palace, but were given the lucrative rights to collect a tax on the wool trade in the Abruzzo. It had been granted numerous rights as a free city under the Angevin kings of Naples, but Charles V curtailed these, and the Lannoy princes ruled absolutely, causing much civic unrest.

The 1st Prince of Sulmona had married Françoise de Montbel, from a Savoyard family also in the service of Emperor Charles V. In particular, she had been one of Charles’s wet nurses, so was always in favour. As a widow, in 1528, she consolidated her family’s position in the Kingdom of Naples by exchanging the County of Asti in the north of Italy for the Duchy of Boiano and the County of Venafro, both in the province of Molise, in the mountains north of Naples.

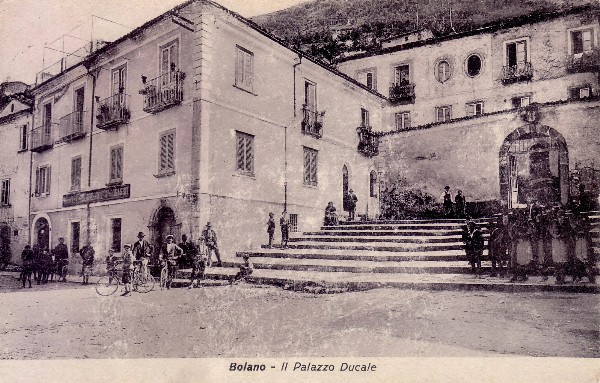

Boiano, or Bojano, had been the ancient city of Bovianum, an ancient city of the Samnites, enemies of the Romans. In the middle ages it was erected into a county for Norman knights who came to Italy with the Hauteville family (who created the kingdoms of Sicily and Naples in the eleventh century)—according to some sources they were called ‘de Moulins’ (‘from the mill’) and eventually Italianised their name into Molise, which became the name of the county and then the province itself. By the fifteenth century it was owned by the Pandone family, close allies of the ruling House of Aragon, and when the 1st Duke of Boaino, Enrico Pandone, sided with the French against Charles V, he lost his lands as well as his head in 1528. The old Norman Castello Pandone di Bojano above the town had already mostly crumbled due to frequent earthquakes in this region, but the Palazzo Pandone in the town centre remained and was given to the Lannoy family. It still stands today.

Enrico Pandone also lost the County of Venafro, a few miles to the west. Here too the Pandone family had rebuilt an older castle in Renaissance style, in the 1440s, famous for its horse frescoes. The Dowager Princess of Sulmona made this her chief residence and raised her many sons here. By the 1700s the Castello Pandone had passed to a major Neapolitan family, the Carafa, and then to others—it is still privately owned.

The eldest son, Philippe de Lannoy (or Filippo de Lanoya), 2nd Prince of Sulmona, retained the great favour of Emperor Charles V, who, in 1534, attended his wedding in Naples to Isabella Colonna, daughter of the Duke of Traetto and widow of the Condottiero Luigi Gonzaga—she was one of the most well-connected Italian aristocrats of the day. As a wedding present, the Emperor gave them the Castello Capuano, one of the two oldest palaces in Naples, though they didn’t hold on to it for long—the new viceroy appropriated it (in exchange for another palazzo, today’s Palazzo d’Aquino in the Via Medina) to build his centralised judicial complex, which it remained for several centuries.

The 2nd Prince was also a soldier, leading the imperial cavalry in Charles V’s wars against the Duke of Saxony. He died relatively young in 1553, and was succeeded by his son Carlo. Carlo renounced his titles only a few years later, so it was Orazio de Lanoya who became Prince of Sulmona and Count of Venafro, between 1559 and 1597—though he sold Venafro and Ortona in 1582. He was a colonel in the Spanish infantry and married a daughter of Alfonso d’Avalos, Marchese di Pescara, a Spanish family that had also become ‘Neapolitanised’. The 4th Prince was succeeded by his son Filippo II, who died fairly young in 1600, leaving a small child, Filippo III, who died in 1604. Sulmona returned to the Crown and in 1610 was given out again as a principality to the Borghese family, who retain the title still today.

Meanwhile, the Duchy of Boiano had been given by the 1st Princess of Sulmona to her second son, Ferrante (or Ferdinand). He sold it in 1538 to his brother Giorgio, and as Comte de la Roche, moved north back to the Low Countries, where he served as an imperial artillery general and married a daughter of Nicolas Perrenot de Granvelle, one of the chief advisors to the Emperor in the Low Countries and Germany. Due to these connections he was appointed governor of several key places in the Low Countries and the Franche-Comté (the home of the Perrenot de Granvelle clan) and became a military engineer and cartographer there.

Giorgio, 2nd Duke of Boiano, stayed in Italy and married another daughter of a Neapolitanised Spaniard, Giulia Diaz Carlon, Countess of Montovia. Their first son Carlo became 3th Duke, while their younger son Costantino entered the church and was briefly Bishop of Vico Equense, on the Bay of Naples. Carlo de Lanoya died in 1575 and the Duchy of Boiano passed by marriage of his daughters into the Carafa family. The Italian chapter for the House of Lannoy came to an end.

Back in the Low Countries, the junior branch of Molembais continued into the seventeenth century. Scanning the family tree we see numerous sons and daughters in positions of authority within the Habsburg court in Brussels: Baldwin II was Premier Maître d’Hôtel for Mary, Duchess of Burgundy, then for her husband Emperor Maximilian, and was appointed to lead the household of their son, Archduke Philip the Fair, as his steward: upon that prince’s coming of age, Baldwin de Lannoy-Molembais accompanied him to inauguration ceremonies in all the provinces of the Low Countries, notably in Leuven in September 1494 where he was sworn in as Duke of Brabant, and in July 1495, when he had his grand ceremonial entry into Brussels. Lannoy’s son Philippe would later become head of the Council of Finances and Grand Maître of the Household of Mary of Hungary, Charles V’s sister, when she was appointed Governor of the Low Countries in the 1530s; and his two sons in turn would act as governors of Hainaut and Tournai. This branch died out in the 1590s (though this is where the claimed descent to the Delano family of America fits in).

The next branch down were the lords of La Motterie, another fief on the borders of Belgium and France northeast of Lille. Claude de Lannoy was created Count of La Motterie in 1628 by the King of Spain—by this point, the Low Countries had been divided into the Dutch Republic in the north and the Spanish Netherlands in the south. He was successively Governor of Maastricht (1616), Namur (1634) and Luxembourg (1638), and Camp Master General for Philip IV, serving as a Spanish commander in the Thirty Years War and a member of the war council of the governor general in Brussels.

His marriage to Claudine d’Eltz, from an old noble house from Luxembourg, brought into the family the Barony of Clervaux: Clerf in German, Klierf in Luxemburgish. This compact territory, fairly autonomous within the northern reaches of the Duchy of Luxembourg consisted of a twelfth-century castle and a large abbey, the Abbey of St. Maurice and St. Maur. It was built by the Count of Sponheim, a member of an extensive noble family that dominated the remote hills and valleys of this area of the northern Ardennes; its large round towers were added in 1400 by the noble Brandenbourg family. The Lannoy family would possess the barony of Clervaux until it was sold in the 1920s. Claude de Lannoy enlarged it by building its impressive ‘Knights’ Hall’. Badly damaged in World War II, the castle was restored and now serves as the seat of the local administration and a regional history museum.

The 1st Count had two sons founding separate lines of La Motterie and Clervaux. Starting with the junior line, we come to the second princely title for the House of Lannoy. Adrien-Gérard, Count of Lannoy-Clervaux (d. 1730) was Governor of Namur, and lord of the ‘libre terre’ of Bolland. This ‘free land’ and its castle were located in the old Duchy of Limburg, today’s Province of Liège, where feudal boundaries were often quite blurry. The castle was built in the sixteenth century and was held by the Lannoys into the nineteenth century—it remains in private hands today.

In 1789, Count Florent-Stanislas married Clémentine-Joséphine de Looz-Corswarem, daughter of the Duke of Looz-Corswarem, one of the few ducal titles in the Austrian Netherlands (see Beaufort-Spontin), who later became 1st Prince of Rheina-Wolbeck. The 1st Prince, Wilhelm von Looz-Corswarem, only ‘reigned’ for a few months in 1803 then passed his title to his son, Joseph Arnold. And when he died in 1827, the claims to this title passed to his brother-in-law Lannoy (Clémentine died the year before).

Rheina-Wolbeck was an unusual principality, a tiny sliver of land running along the west bank of the River Ems northwest of the city of Münster. Rheine was an old city in a region known as Münsterland, the lands belonging to the Prince-Bishopric of Münster; it also bordered the imperial counties of Lingen and Bentheim (on the very western edges of Germany’s modern borders). Wolbeck was also part of the Prince-Bishop’s lands, just outside the city on the southeast, with a fortified castle to which the bishops retreated when their citizens became unruly (like so many bishops of the Holy Roman Empire, they were forced to reside outside their episcopal city). With a mighty octagonal tower at its centre, over the centuries it developed into a hunting lodge, with a zoo added in the early eighteenth century. But all this was destroyed in the Seven Years War and almost nothing remains of Burg Wolbeck.

In 1803, most of the ecclesiastical states of the Holy Roman Empire were secularised and given to other princes. Münster was the same. As a result of the Treaty of Lunéville two years before, aristocrats from the Austrian Netherlands who lost their lands to ever-expanding French conquests were compensated on the far side of the Rhine. The Duke of Looz-Corswarem was one of these, and this rather strange new state was created for him though he was at first slow to claim it. Apparently he considered Rheina to be a better latinised form of the name, rather than Rheine. One of the few real sources of income was a toll on a bridge over the River Ems which flows due north into the North Sea. There were plans to develop the Ems for better river transport, but only three years later, the principality was dissolved and its lands given to the new Grand Duchy of Berg, ruled by Napoleon’s brother-in-law, Joachim Murat. In 1811, the lands on the left bank of the Ems were incorporated directly into the French Empire. As Napoleon’s empire began to collapse in 1813, Duke Wilhelm von Looz-Corswarem’s son, Joseph Arnold, tried to reclaim the Principality of Rheina-Wolbeck. But in the Congress of Vienna of 1814-15, these lands (along with most of the Münsterland) were given to the Kingdom of Prussia as part of the new Province of Westphalia. Some of the lands, however, he was allowed to keep, notably the former Abbey of Bentlage.

Bentlage was founded as an abbey for the Order of the Holy Cross (sometimes called the Crusader Brothers) in 1437. It was never huge and by the eighteenth century had only about a dozen resident friars. It was secularised in 1803, and given to the new Prince of Rheina-Wolbeck as its seat. When Joseph Arnold died in 1827, the property passed to Count Florent-Stanislas de Lannoy-Clervaux, and it stayed with his descendants, renovated as a country seat, until 1912, then passed back to Looz-Corswarem heirs, until they died out in 1946 and it passed to another family. Acquired by the city of Rheine in 1978, it has been turned into a museum.

Florent-Stanislas de Lannoy-Clervaux’s succession to these lands, but also to the (now empty) title of Rheina-Wolbeck, was contested. It wasn’t until 1840 that the Bentlage estate was confirmed as his, and the King of Prussia re-created the title Prince of Rheina-Wolbeck for his heir, his grandson Napoléon de Lannoy, though without any sovereignty, merely the top of the noble hierarchy in the Prussian House of Lords. The title and seat were confirmed again in 1878 by Emperor Wilhelm I for the 3rd Prince of Rheina-Wolbeck (with the style ‘His Princely Grace’), Arthur de Lannoy. By this point the family was living mostly back in Belgium, and Bentlage was neglected. Arthur never married and was succeeded in 1895 by his brother Edgar who died in 1912. He did have a son, but his marriage was deemed unequal by the standards of Imperial princes, so the title and estates passed back to Looz-Corswarem heirs. This branch of the family (Lannoy-Clervaux) died out by the end of the twentieth century.

Returning to the more senior line of Lannoy-La Motterie, Philippe, 2nd Count of La Motterie, was Maître d’Hôtel of Archduke Leopold and Don Juan de Austria, successive governors of the Spanish Netherlands, though this latter appointment was cut short as he was killed in 1658 in the Battle of the Dunes against France. By his second marriage, he brought in another significant fief, Beaurepaire, in southern Hainaut (now also in France).

As this branch grew and spread in the eighteenth century, their actual title, Count of the Empire, was applied by different sons to different estates they acquired: Annapes, Watignies, Beaurepaire. In a junior branch, Eugène-Hyacinthe, 5th Comte de la Motterie, was Governor of Brussels (1737), a Field Marshal and Artillery General in the Imperial Army, and ultimately Grand Marshal of the Court of Brussels, 1751-56.

His son Chrétien-Joseph (d. 1822) was Imperial Lord Chamberlain from 1756, a leader of the court of Prince Charles of Lorraine, Governor-General of the Austrian Netherlands from 1741 to 1780. He resided at the Hôtel de Lannoy in Brussels. Before he died, Chrétien-Joseph, like many nobles had to adapt to his country being absorbed into the French Empire, so in 1804 he accepted a position as Senator of France, and in 1808, Count of the Empire. The line of La Motterie died out with him, while his cousins, the counts of Beaurepaire continued until 1870.

The Hôtel de Lannoy is on the rue aux Laines (or Wolstraat, ‘wool street’), a street popular with aristocrats from the fourteenth century, on the edge of the old city, south of the Coudenberg, the seat of the court (today’s Royal Palace). It was built as a city residence for the family in the eighteenth century, across the street from the grand Palais d’Egmont and its large gardens. There was also a Hôtel de Lannoy built in the 1770s, closer to the Royal Palace, sold to the Ligne family in the 1830s, so today known by that name.

The senior line, who used the title more straightforwardly as ‘Comte de Lannoy’, came into greater prominence in the nineteenth century. Gustave-Ferdinand (d. 1892) was Chamberlain of King William I of the Netherlands, then after Belgium declared its independence in 1830, Grand Master of the Household of the Queen of the Belgians.

His country seat was the Château d’Anvaing, in the town of Frasnes-lez-Anvaing in Hainaut. Originally built by Jacques de Boubaix in 1561, in the style of a Renaissance water castle, it was then acquired by the Lannoy family in 1781. Extensive French-style gardens had been added in the early eighteenth century, and in about 1800 the estate was modified again, turning the old moat into a proper lake and refashioning the castle to have a more medieval ‘defensive’ look again becoming popular for aristocratic dwellings. Anvaing became famous in the twentieth century as the site of the capitulation of the Belgian Army in May 1940. It remains the main seat of the Lannoy family.

In the twentieth century, Philippe, Count of Lannoy (d. 1937), was Marshal of the Court of King Albert II of the Belgians—when the latter died, the Marshal was responsible for organising his funeral. He then became Grand Master of the Household of the now widowed Queen Elisabeth. Hie grandson, another Philippe, Count of Lannoy (d. 2019), was a provincial councillor of the Province of Hainaut. He and his wife, a member of an Antwerp family ennobled in 1614 (della Faille de Leverghem), had seven children and then one more after a gap of eight years: this is Countess Stéphanie, the new Grand Duchess of Luxembourg.

(images Wikimedia Commons)