In ancient times there was a road, the Via Domitia, built by the Romans to bring soldiers and trade across the Alps from Italy into southern Gaul, then south to Spain. Cities and towns along this route that hugged the Mediterranean prospered, and fortified positions held by noblemen kept trade safe, and of course provided financial gains. One such fortification was on a rise above the road as it passed between the towns of Lunel and Montpellier: Castries.

Castries took its name from the Roman castrum or fort established to watch over the road. By the tenth century there was a feudal lord and a simple castle. In the middle of the twelfth century, this became part of the much larger lordship of Montpellier—which in the thirteenth and fourteenth century was held by the House of Barcelona, kings of Aragon and Majorca, until sold to the French Crown in 1344. In the fifteenth century, the castle and lordship were alienated by the Crown to the family de Pierre (or Peyre) de Pierrefort, who sold it to a cousin, Guilhem Lacroix in 1495. His descendants completely rebuilt the old castle in 1520, and again in the 1670s as an enormous palace, a display of great wealth and power in the region. It is this grand château, with golden walls that shine in the light of the Mediterranean sun, that stands today, referred to locally as the ‘Petit Versailles’ of Languedoc. It has recently been restored, but is not yet open for visits, as I recently discovered in my travels through this region.

Who was Guilhem Lacroix? His family were merchants from Montpellier who had amassed great wealth on the Mediterranean fish market, then became money changers, then bankers. In the fourteenth century, their name was Le Cros or Lacroux; by the end of the fifteenth century, it was La Croix de Castries, one of the powerful baronial families of Languedoc. Over the centuries, they drew nearer and nearer to the royal court, given a marquisate in 1639, then a dukedom in 1784. As with many of the grandest families at Versailles, this family history rooted in trade was not something to boast about, so seventeenth-century genealogists hoping to please (and to be remunerated) came up with new ancestors: in this case, the La Croix family were said to be descended from a knight, Jean ‘of the Cross’, a landholder in Languedoc in the 1320s. The family’s coat-of-arms supported this: a golden cross on a blue field. Jean was connected by these genealogists to a prominent contemporary holy man, Saint Roch, born in Montpellier. Saint Roch himself, they wrote, was descended from the ancient lords of Montpellier, who were an offshoot of the earliest line of French kings, the Merovingians. As proof, one author asserted that the La Croix family had frequently been protected from the plague by Saint Roch (one of his specialities). Another early ancestor was added for good measure: another Chevalier Jean de La Croix, who had bravely fought in the resistance against the English in Anjou and defeated the Duke of Clarence at the Battle of Beaugé, 1421.

The truth is less poetic. Guilhem (or William) Lacroix, wealthy banker, was elected as one of the consuls of the city of Montpellier, in 1465, and a counsellor in the Cour des Aides, the financial court for the city with jurisdiction over this part of the province of Languedoc. He was appointed President of the Cour des Aides in 1487, which was an ennobling office (and for which he undoubtedly paid). This was the era in which French kings were establishing real control for the first time over the southernmost parts of the Kingdom, so the now noble Guilhem de La Croix became a trusted servant of kings Louis XI, Charles VIII and Louis XII. He frequently served as President of the Estates of Languedoc (the meeting of the three orders—clergy, nobles, commons—at a provincial level) in the 1470s-90s, and in 1495 his rise was crowned when he was appointed royal governor of the city of Montpellier itself, and purchased the Barony of Castries, which made him one of the barons of Languedoc, with a permanent seat at the Estates, no longer a member of the ‘commons’.

His son Louis took over as Baron of Castries in 1502 and continued his father’s role as servant of the Crown in this far end of the Kingdom. In 1517, he was deputy of the city of Montpellier to a national assembly of the nineteen most important cities of France, then in 1519, he was appointed Commissioner of the King at the Estates of Languedoc. Louis (the name surely reflects the family’s loyalties) also married well, to an heiress of lordships in other parts of the Midi, in Languedoc, Auvergne and Limousin.

Over the next century, the barons of Castries served in the king’s armies and as representative of the Crown at the Estates of Languedoc and as consuls of Montpellier. They continued to intermarry with the administrative elites of their city and the local nobles of the province. When Baron Jacques died in 1575, his estates were divided between his two very young sons: the younger son, Gaspard, was given the lordship of Meyrargues, in Provence, and formed a separate branch of the family, to which we will return below. The elder, Jean, retained the lands in Languedoc, but moved the family’s interests more solidly to court by obtaining the posts of Gentleman of the Chamber and Captain of the King’s Lances—though he died only aged 21 in 1592. He did leave a son, another Jean, who continued the dual tradition between court and provinces: serving in the local military under the governor of Languedoc, the Duke of Montmorency, attending the provincial estates as one of the ‘premier barons’, but also attending the King at court as a Gentleman of the Chamber. Perhaps more importantly, he married Louise de l’Hôpital, Dame d’honneur of Queen Anne, whose family was on the rise at court.

It was probably this connection that persuaded the King to favour their son, René-Gaspard, with the rank of marquis in 1639. He also took up his father’s post as a Gentleman of the Chamber that year. This first marquisate is a little vague, seemingly not erected on the barony of Castries, but referring to the already extant marquisate of Varambon, in southern Burgundy, recently confiscated from the Rye family, to whom René-Gaspard returned it in 1641. Four years later, it was Queen Anne who normalised the situation by making a marquisate of Castries fixed firmly on that barony in Languedoc—and thus retaining his prominence in the estates there, where he was also named ‘Councillor of State of the Sword’ an honorary position within the nobility as a representative of the Crown.

The Marquis de Castries rose in the ranks of the military to lieutenant-general, 1660, and was appointed Governor of Montpellier (and of the chief port nearby at Sète), then Lieutenant-General of Languedoc (essentially second in command to the royal governor) in 1668. As military arm of the government of Languedoc, he was sent in 1670 to suppress Protestant unrest in the Cévennes. He also was in charge of presiding over the Estates if the governor was absent, and it was with this in mind that he significantly enlarged his château at Castries, with the idea of hosting the Estates there—a real sign of wealth and prestige. He invited the King’s gardener Le Nôtre to send plans for the redesign of his gardens and fountains, for which he even built a special aqueduct, bringing water from seven kilometres away. The Aqueduct de Castries still stands.

The next bastion of French elite society that the La Croix de Castries family needed to conquer was the Church. And in this they were aided by the Marquis de Castries’ wife’s brother, Cardinal de Bonzi. Bonzi was a member of a Florentine family who had held several of the most prominent episcopal sees in the south of France for generations—he himself was Archbishop of Narbonne and an important diplomat for Louis XIV in Italy. The Cardinal provided his nephew Armand-Pierre a post as Archdeacon of the Cathedral of Narbonne (not far from Montpellier) and several abbeys in Languedoc. At court, the Abbé de Castries was appointed an almoner in the household of the Duchess of Burgundy (married to the King’s grandson), then of the Duchess of Berry, the daughter of the Regent of France, the Duke of Orléans. It was the latter who appointed Castries to the archbishopric of Tours in 1717, but only two years later he transferred to the archbishopric of Albi, in Languedoc. Also in 1717, the Regent admitted Castries onto the Royal Council of Conscience (one of the various councils that governed France during the minority of Louis XV). But he did not become a major force in the French Church and lived quietly for another three decades.

His brother Joseph, 2nd Marquis de Castries, was also set up well, with a marriage to a niece of Madame de Montespan (and a chief lady-in-waiting to the King’s sister-in-law, the Duchess of Orléans), and succeeded to the family offices of Lieutenant-General of Languedoc and Governor of Montpellier in 1674. His eldest son died in 1717, at 23, followed by his wife in 1718. A few years later he was married again, to the daughter of the Duc de Lévis, who was also Count of Charlus (in Limousin), which passed to the La Croix de Castries family at the death of her father in 1734.

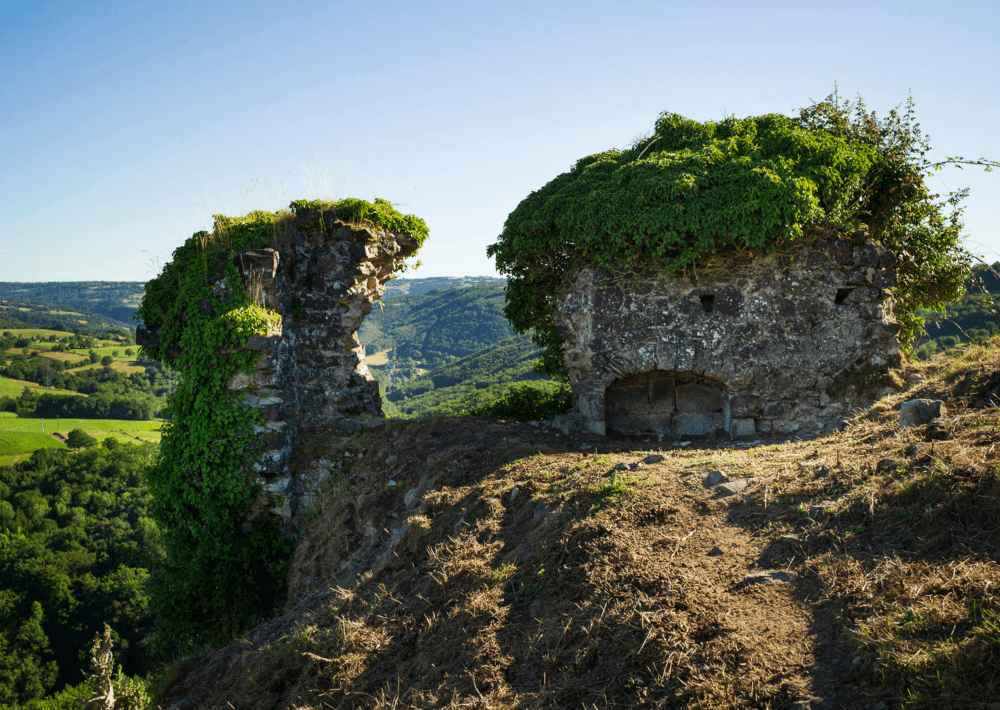

Charlus was an ancient fortress on the ‘Pic de Charlus’ a hilltop on the borders between Upper Auvergne (the Cantal) and Limousin. It had played its part in the wars between the kings of France and England, but by the eighteenth century was only a ruin. It did not become a La Croix de Castries residence.

The eldest son of this second marriage, Armand-François, became 3rd Marquis de Castries in 1728, and Governor of Montpellier—though he was only three. He grew up to be a soldier, but died in 1743 in the War of Austrian Succession. His brother Charles-Eugène was also a soldier, and became the most well-known member of the entire family.

The 4th Marquis de Castries and Comte de Charlus had a long career as a soldier, and also maintained the family offices in Montpellier and Languedoc. He made his name as a cavalry officer in the Seven Years War, notably achieving victories on land, but he also led a naval expedition to secure France’s interests in the West Indies in 1756—capturing the island of Saint Lucia from the British and later renaming its capital city Castries. After the war he was took up a court post as Commander of the King’s Gendarmes (1770). In 1780, Louis XVI appointed him Minister of the Marine, an important position as France geared up for war once more with Great Britain in defence of the independence of the United States. He re-organised the fleet (in shambles since France’s massive defeat in 1763) which was key to America’s victory at Yorktown in 1781. But in the latter part of the war, tried to secure France’s interests in the Indian Ocean as well (notably defending the Mascarene islands, today’s Réunion and Mauritius), with less success. The King rewarded Castries with the baton of a Marshal of France in 1783. He had become a friend and ally of the reform minister Jacques Necker, whose disgrace in 1787 led to the Marshal de Castries’ resignation as Minister of the Marine, though he was compensated with the post of Governor of Flanders and Hainault. He refused the King’s request to take up this post again in July 1789, when Necker was asked back as Finance Minister, and when things heated up for the aristocracy in October, he left France to stay at Necker’s house in Switzerland.

As the army of French exiles (the émigrés) began to form in the Rhineland in 1792, the Marshal de Castries became commander of a brigade (though he saw little action himself). He became chief military advisor and Head of the Council of Louis XVI’s brother, who formed a government in exile after the King’s execution in January 1793. A few years later, while visiting Wolfenbüttel, the capital of his old adversary in the Seven Years War, the Duke of Brunswick, he died.

Close to Paris and to the court at Versailles, the Marshal acquired the Château of Ollainville, south of the city, which had once been a country retreat enjoyed by Henri III in the 1570s, and was now remodelled by Castries in the 1780s; and also nearby a follie or garden house in Antony, close to the Château of Sceaux. Both properties were confiscated in the Revolution and demolished in the nineteenth century; the latter is now the site of Parc Heller.

In the city itself the Marshal lived at the Hôtel de Castries, which he rebuilt in a more up-to-date style in the 1760s using money he inherited from his uncle, the Marshal de Belle-Isle. This hôtel particulier was built on the rue de Varenne in the faubourg Saint-Germain in the late seventeenth century by the Seigneur de Nogent. It was sold to the La Croix family in 1708, purchased with money from Cardinal de Bonzi. In 1790, after the Marshal left France, the house became the seat of the Ministry of War, then was returned to the family. Rebuilt by the 2nd Duke of Castries in the 1840s, the Hôtel de Castries then passed to other aristocratic families by marriage after 1886, until acquired once more by the French government in 1946, which housed the Minister of Agriculture here—which was succeeded by various other ministries until the present (recently it has been the seat of the Ministry of Housing and Urban Development, and its successor in charge of migrants, which drew the attention of the public when complaints were made in 2017.

The Marshal had only one son, Armand-Charles-Augustin, who became the 1st Duke of Castries in 1784. This was in part an honour by the King for his father, the Marshal, but also for his father-in-law, the Duc de Guines, former ambassador to Prussia and Great Britain, whose daughter Marie-Louise-Philippine he had married in 1778. Both duchies (Guines and Castries) were ‘by brevet’ meaning a royal order and were not full duchy-peerages, received as peers in the Parlement of Paris. It was agreed that Louis XVI would transfer the ducal title more formally, with a peerage, for Castries once Guines died—but this did not happen until 1806 (and in fact by then his daughter was already dead). Meanwhile, the Count of Charlus (as he was known, as the heir) was establishing his own career in the shadow of his father, as a soldier in the American War of Independence (notably at Yorktown in October 1781), then as Lieutenant-General of Lyonnais, Forez and Beaujolais in 1782. The Duc de Castries was selected as a deputy for the nobility to the Estates General of Spring 1789, and was at first progressive and a supporter of reform (including the abolishment of noble privilege). But as the Revolution radicalised in the Autumn, he became increasingly royalist, defending the King’s prerogatives in government. He remained in Paris until late 1790, after he had fought a duel with a political opponent in a very aristocratic manner and was hounded in the press for it, and an angry mob sacked the Hôtel de Castries. He fled to Switzerland and joined the émigré cause opposing the Revolution. When he returned to France in the Restoration of 1814, Louis XVIII named him a lieutenant-general in the army and in 1817 finally normalised his title as a duke and peer of France. He retired form active service and died two decades later in 1842.

The 2nd Duke of Castries was his son, Edmond, born just before the Revolution. Unlike his father, he was a supporter of the Empire of Napoleon, and served in the Imperial army in 1809-13, including the long campaign into Russia. In the Restoration he rose to the rank of maréchal de camp, but was not particularly noteworthy as a soldier. His wife, Claire, daughter of the Duke of Maillé, was more prominent, known for hosting a Paris salon at the Hôtel de Castries in the faubourg Saint-Germain, and indeed for her scandalous extra-marital relations. One of these was with the son of Prince Metternich, Chancellor of Austria (which produced a son in the 1820s); while another was with the writer Balzac in the 1830s, which was not physical (or was it? online sources are cagey), but consisted of intense literary exchanges, and she is noted as the model for some of his novels (both in a good and bad way).

The 2nd Duke of Castries died in 1866, and was succeeded by his nephew, also called Edmond, a lieutenant in the army. The 3rd Duke died twenty years later in 1886, only in his fifties. His sister Elisabeth maintained the family prominence as the wife of Patrice de MacMahon, Duke of Magenta, President of the Third Republic in the 1870s. When she died in 1900, the senior line ended. The hôtel in Paris and the château in Languedoc passed to the Harcourt family, by means of the last duke’s mother, Marie-Auguste d’Harcourt.

A junior line continued, descended from the lords of Meyrargues, noted above. Formally created ‘Count of Castries’ in the Restoration (1821), they included several prominent soldiers and colonial explorers in the century that followed, and after 1886, sometimes assumed the title ‘Duc de Castries’, though they had no legal right to it. The most famous of these was the historian René de La Croix de Castries, 4th Count of Castries. As a young man, in 1935, he purchased the Château de Castries from the Harcourt family, and spent considerable time and money to bring it back to its former glory. He was mayor of the town of Castries in the 1940s, but soon moved to Paris where he became known as a historian of the French monarchy and nobility (publishing as the ‘Duc de Castries’). After establishing his reputation as a writer, he was elected to a chair of the Académie française (1972), and President of the Society of the History of France (1974), then president for a term of the Institut de France, the leading association for arts and sciences in France (Spring 1982). He was also President of the French branch of the Society of Cincinnati (1975), a reflection of his family’s prominent participation in the American War of Independence. He died in 1986, and was succeeded in his role for the Cincinnati by his first cousin, François, whose son Henri de Castries is today one of the most influential businessmen in France.

(images Wikimedia Commons or public domain websites)