The new Netflix series Il Gattopardo (‘The Leopard’) is the third adaptation of the celebrated novel by Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa. Published in 1958, it was first a hugely successful film by Visconti in 1963, then a BBC radio drama in 2008. Telling the story of a powerful landowner from the old aristocracy of Sicily dealing with the changes brought about by the Risorgimento of the 1860s—the unification of Italy—the historical novel is considered one of the very best of its genre. What makes it particularly interesting for a historian or a sociologist (or a historical sociologist) is that the author was himself a prince, and modelled the main character (the ‘Prince of Salina’) after one of his own ancestors, either his maternal great-grandfather, Alessandro Filangieri, Prince of Cutò, or his paternal grandfather, Giulio Tomasi, Prince of Lampedusa. It is therefore potentially full of real insights (or potentially full of falsehoods or ‘desired truths’ … one can never be certain) from a person who grew up within the social caste under examination—in a similar way that Julian Fellowes is able to write about his own class in Gosford Park or Downton Abbey.

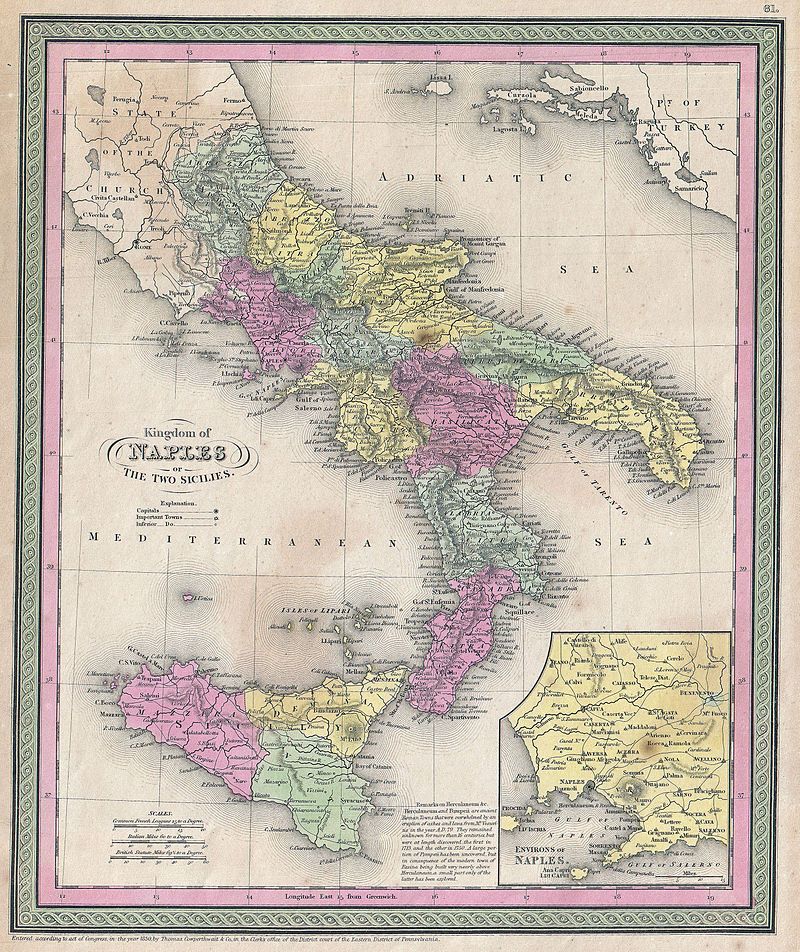

There are several characteristics that are striking about the Sicilian high aristocracy and make them different to other dukes and princes in this blogsite. For starters, most of them do not have a particle (a ‘de’ or a ‘von’) to show they are nobly born—their surname is sufficient; in the case of Lampedusa, it is Tomasi. Secondly, their numbers are inflated, with over one hundred princely titles, meaning that the power of that title is somewhat diluted. Yet thirdly, they were actually incredibly powerful as landowners and political players well into the modern era for the simple fact that for much of its history, Sicily was governed from afar and its magnates were left to mostly manage their own affairs. This is in fact the major crisis facing the Prince of Salina in the novel. From the early fifteenth century, Sicily was ruled from afar, either from the Kingdom of Aragon, then after 1734 by a new regime based in Naples, the Bourbons. When, in the Netflix series, the Prince of Salina is described as a ‘Bourbon prince’ it is a bit misleading, since the Sicilian aristocracy only tolerated their Bourbon kings as long as they stayed far away on the mainland and left their local autonomy untouched. This ‘understanding’ was tested by events during the revolutionary era at the very end of the eighteenth century when the royal family had to flee Naples and took refuge in their second capital in Sicily, and tested again when Sicily erupted in revolution again in 1848 and briefly deposed the Bourbons. Still, the princes saw it in their best interests to maintain the status quo, and to not join in the nationalist movement sweeping the Italian peninsula at the end of the 1850s, which planned to join together the multiple duchies and principalities into one unified—and politically liberal—Kingdom of Italy.

By this point, most of the oldest Sicilian noble families knew they could weather the storm—though they didn’t have a ‘de’ or a ‘von’ like other princely families, a name like Lanza or a Filangieri drew power from their ancientness, going all the back to the Norman conquest of this island in the eleventh century. The Tomasi were different: their position as magnates only dated back to the late sixteenth century (though see below for grander claims). But they cleverly hitched their star to the heritage of one of these oldest families, the Chiaromonte—a literal translation from the French ‘Clermont’—who arrived with other Normans and held the highest offices in the Kingdom for centuries. Eufemia Chiaromonte inherited the lordship of Montechiaro (a reversal of her surname), and in about 1408 took it in marriage to the Caro family. The Castle of Montechiaro is perched on a cliff high above the sea on the south coast of Sicily, southeast of the provincial capital of Agrigento. Built in the 1350s, it was an important defensive structure against raids by pirates from the North African coast, also known as the ‘Barbary Pirates’, who frequently raided this coast to capture slaves.

At some point, the Caro family were also created barons of Lampedusa, an island about 200 km off the southern coast of Sicily—in fact closer to the coast of Tunisia (about 100 km). It was considered to be a sovereign lordship, sort of like the island of Malta, 175 km to the east, which probably was the reason it was chosen later for the Tomasi family’s princely title. The lordship included the nearby smaller island of Linosa, with its distinctive volcanic peaks. Both islands are part of the Pelagian Islands, settled and fought over since antiquity by Phoenicians, Greeks, Romans, Saracens, Knights Hospitaler and so on. The kings of Sicily entrusted the lordship to local baronial families to try to ensure their overlordship over these strategic stopping points in Mediterranean traffic. But they had little other value—there was little water and were mostly rocky and infertile. Sometimes the island had residents, and sometimes not. In 1553, for example, pirates under the command of the Ottoman Empire carried off 1,000 people into slavery. Just over a decade later, Lampedusa was a useful stopping off point for the Spanish navy on its way to relieve Malta from a besieging Ottoman fleet.

In 1583, the heiress of both Lampedusa and Montechiaro lordships, Francesca Caro, married Mario Tomasi, a captain in the Sicilian army based in the nearby town of Licata. His father, Giovanni, was said to be from Campania on the mainland, while his mother was from the Roman nobility. Much grander claims have been put forward by various genealogists, starting in the seventeenth century (and continuing in the present), to connect this family to the other branches called Tomasi or Tommasi all over Italy, and also to a family called the Leopardi—which makes a nice connection to the title of the novel and its fictional prince, ‘the Leopard’. There are stories about a certain Thomas Leopardi, a Byzantine soldier in the sixth century who descended from Licinius ‘the Leopard’, a grandson of Emperor Constantine. His sons moved to Ancona in central Italy and took the name Tomasi. From here various branches spread all over the peninsula, from Verona to Siena to Capua. One family who stayed in the area of Ancona (the Marche), seem to have assumed the title ‘Prince Tomassini’, or Tomassini-Leopardi, and put forward claims in the later twentieth century to be the ‘true heirs’ to the Byzantine Empire. Let’s take that with a grain of salt. But the Tomasi di Lampedusa family of Sicily did use a leopard on their coat of arms—some sources say it is a serval, a smaller cat from North Africa, but this is probably a reference to the fact that a gattopardo is a serval, and literary critics have suggested that Tomasi chose this name to represent a more local cat, one that was being hunted to extinction in the nineteenth century, like the protagonist of his novel.

The family rapidly expanded their power in southern Sicily in the seventeenth century, and if they didn’t take on a mantle of ‘Byzantinism’, they certainly became known for their extreme piety and devotion to the Catholic Church, producing a ‘Holy Duke’, a ‘Holy Prince’, a venerable nun and a canonised cardinal. The piety of the book Il Gattopardo and the film and television series clearly reflects this same strong piety in the family two centuries later.

This started with Mario and Francesca’s twin grandsons, Carlo and Giulio, born in 1614, the year their father, Ferdinando Tomasi, was formally invested with the lordships of Montechiaro and Lampedusa. The elder twin founded a new town, Palma, slightly inland from the old fortress, on the site of an ancient Greek settlement. In 1637, he obtained full governing powers over the town from the King of Spain (Philip IV, who was also King of Sicily), and a year later was created Duke of Palma. The new town, laid out on an orthogonal plan, was situated in a green valley watered by a river that emptied out into the sea at a newly built marina. It was constructed by the twins and their uncle Mario, an officer of the Catholic Church in Sicily and governor of the nearby town of Licata. Its main focus point was a new church, Santa Rosario, and a new Benedictine abbey, which incorporated the ducal palace in Palma. This was replaced with another palace in the 1660s—after centuries of neglect, it was recently restored, and though quite plain on the outside, has preserved wonderful wooden ceilings with dynastic symbols and heraldry.

But just two years later, Duke Carlo retreated from the world and became a Theatine monk, ceding his new title to his twin brother Giulio. That same year, the latter married Rosalia Traina, heiress of the barony of la Torretta, a small village on a mountain built around a ‘little tower’ overlooking Palermo. Its castle had been recently rebuilt in the 1590s and was later expanded into a baroque palazzo. This was ‘lost’ in 1954—I can’t find anything more about this online. Alongside several other lordships, Donna Rosalia’s inheritance placed the Tomasi family at the top rank of Sicilian landowners. Torretta brought in income from its olive groves, but more importantly, was a base of operations for involvement in national politics in the Sicilian capital, Palermo.

Duke Giulio’s civic and political activities had mostly been confined to Palma’s nearest large town, Licata, but it is clear he now moved in higher circles, and in 1667 the King of Spain (now Carlos II) created him a Knight of the Order of Santiago and 1st Prince of Lampedusa. The Tomasi family had now fully arrived.

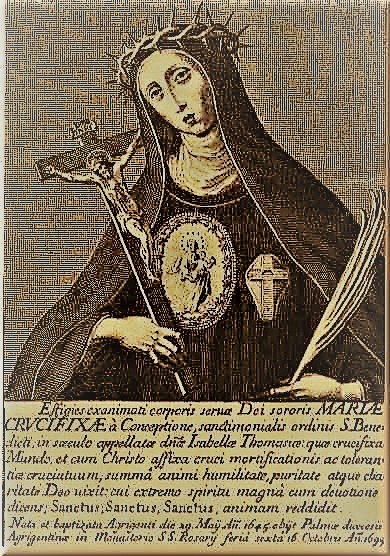

Both Giulio and Rosalia were known for their piety—he’s nicknamed ‘il Duca Santo’. After they had six children, they agreed to live together chastely. But in about 1660, obtained permission from the Pope to formally separate; he retired to a monastery like his brother, while his wife and four daughters retreated the new cloistered Benedictine monastery of Palma: his wife as ‘Suor Maria Seppellita’, his eldest daughter Francesca as its abbess, and Isabella as ‘Suor Maria Crocifissa’. The latter became known for her extreme devotion to penance and suffering, and for a letter dictated to her in her cell by Satan himself in 1676, written in demonic language and still undeciphered, despite recent attempts using decryption and AI software. Sister Maria of the Crucifixion is known as ‘Blessed Corbera’ in Il Gattopardo (Corbera being the surname of the fictional family of the Prince of Salina). Shortly after her death in 1699, the Bishop of Agrigento ordered a hagiographic biography to be written and requested the opening of a case for her beatification, but she only got as far as being declared ‘venerable’ in 1787.

It was her sibling, the eldest son Giuseppe Tomasi, who made it fully to sainthood. He renounced his claims to the succession in 1665 and entered the Theatine Order as his uncle had done. This order, founded as part of the wave of Catholic reforms in the sixteenth century, was devoted to simple living and to clerical reform. Giuseppe moved to Rome where he became an expert at deciphering, editing and publishing ancient liturgical texts, some in Hebrew, some in Aramaic, or other languages (some called him the ‘Prince of Roman Liturgists’). At the start of the eighteenth century, he became particularly close to a new pope, Clement XI, who named him ‘examiner’ of bishops and abbots (to satisfy his zeal for reform), and also member of a number of theological bodies in Rome. The Pope made him a cardinal in May 1712, but Giovanni died at the start of the new year. He was beatified about a century later, and finally was canonised as a saint in 1986.

This saint’s secular younger brother, Ferdinando, 2nd Prince of Lampedusa, was no less holy, and, similar to his father, earned the nickname ‘il Principe Santo’. Though it hardly seems he had the time: he married the daughter of another princely family when he was only 18 (and his wife, Melchiorra Naselli, only 15), had a son and died three years later in 1672, as did his young wife.

Young Giulio II, 3rd Prince of Lampedusa, 4th Duke of Palma, Baron of Montechiaro and Torretta, must have been raised by his maternal family, the Nasellis, since all of his paternal family lived cloistered or in Rome. But he too had a very short life. He married another Naselli (Anna Maria), then died age 26 in 1698, leaving a one-year-old child, Francesco II, 4th Prince of Lampedusa. The Naselli family, princes of Aragona (near Agrigento) since 1625, and descended from kings themselves (or so they claimed), undoubtedly helped solidify the young prince’s ties with the distant Spanish monarch in Madrid: in 1724 he was created a Grandee of Spain, and he transferred much of his activities to Palermo, taking his turn, for example, holding the yearlong offices of Captain of Justice and Praetor. He served as president of the confraternity devoted to the rehabilitation of former slaves, re-captured from the Turks, and as royal vicar appointed to deal with the pestilence in Messina in 1743. He twice was selected for the Deputation of the Kingdom of Sicily (a body like the Sicilian Parliament, but meeting more frequently to carry out functions of governing), in 1732 and 1754, and that latter year was appointed to a senior post in the management of the royal patrimony in Sicily. By this point, the royal dynasty had changed, the Bourbons having taken over from the Habsburgs in 1734. But it is interesting to note—though this should be confirmed—that Prince Ferdinando in 1737 was named Gentleman of the Chamber to the Emperor Charles VI, whose Austrian forces had been chased from Sicily a few years earlier. Is this an error in the genealogies, or was the Prince perhaps playing a double game in case the Habsburgs were restored (Sicily having changed hands three times in the previous three decades)?

The 4th Prince also connected himself more closely with the aristocracy of Palermo though successive marriages to two princesses of the House of Valguarnera (remember that name for later). A palace was built, fairly modest and on a narrow street in the inner city close to the port, so there’s no grand vista images to look at. It housed the family during the winter months for the next two centuries, until it was largely destroyed by Allied bombs in 1943. In 2011 the ruined Palazzo Lampedusa was bought by developers and restored for use as Air B&B apartments—which looks spectacular.

Unlike his father and grandfather, the 4th Prince of Lampedusa lived to the ripe old age of 78. When he died in 1775, his estates and titles passed to his son Giuseppe Maria. Like his father, he served in a number of administrative and charitable capacities in Palermo. He also was appointed at one point as ‘ambassador’ from the city of Palermo to the royal court in Naples—which underlines how very isolated Sicily was from its royal family, who maintained a completely separate life in Naples (the King even had two regnal numbers: he was Ferdinand IV in Naples, but only Ferdinand III in Sicily). The 5th Prince of Lampedusa was also Intendant General of the Army of Sicily, 1762, a prominent position, but also lucrative as it would have been accompanied by numerous kickbacks for arranging contracts with suppliers of uniforms, food, gunpowder and so on. The ‘Leopard’ may have protested about the corruption of non-noble administrators like the Mayor of Donnafugata, but in this era, the aristocracy was very much involved as well.

The 5th Prince died in 1792, just before the outbreak of revolution rocked the kingdoms of Naples and Sicily. The 6th Prince, Giulio III, had already filled the same positions as his father and grandfather—head of charitable confraternities, member of the city’s senate, and deputy of the Kingdom—but was also given the title Gentleman of the Chamber of the King of Naples & Sicily. In all the courts of Europe, this title was given as an honour to senior noblemen and did not necessarily mean he attended court personally in far-off Naples. Then in December 1798, the royal family came to him, driven out of Naples by an invading French army (which set up a republic); they fled to Palermo where they resided for a few months, returned to the mainland, then were forced back to Sicily once more in 1806, this time by a more permanent French occupation. During this time, the Prince of Lampedusa was Praetor of the city of Palermo, so would have had certain hosting duties, and he was rewarded with a knighthood in the Order of San Gennaro (the senior chivalric order for the Kingdom of Naples). He died in 1812 before the Bourbons left Palermo, so it was his son who took part in the brief revolution of Sicily itself, that same year, when the King was forced to grant a constitution; Giuseppe, 7th Prince of Lampedusa, was named a peer in Parliament’s new upper house (for his duchy of Palma). But this was short-lived, and after Ferdinand was restored to his throne in Naples, he created a new unified Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, nullifying any political concessions he’d given the Sicilians. A bit of a kick in the teeth to people who had saved his skin twice in the previous fifteen years.

Prince Giuseppe made another good marriage for the family, to Princess Angela Filangieri, daughter of the 6th Prince of Cutò. Her family was much grander, with generals and governors across the centuries; her father was a prominent commander in the Neapolitan army and Royal Lieutenant-General (aka viceroy) of Sicily, 1803-06, a position held later by her brother Niccolo, 1816-17 and 1821-22. Here enters another major setting for Il Gattopardo, in Angela’s family’s country estate: the Palazzo Filangieri-Cutò, in the village of Santa Margherita di Belice, about 60 km southwest of Palermo in the interior of the western corner of the island of Sicily. Originally built by the (actual) Corbera family in the late seventeenth century, it passed to the Filangieri family in the eighteenth century. It was a vast palace, large enough to host Queen Carolina for several months of her exile (1812-13), and was a place the author of Il Gattopardo spent much of his youth, so is the inspiration for the fictional Donnafugata. It was in fact used as such for the Visconti film of 1963, but was almost entirely destroyed by an earthquake in 1968. Only a shell remains. In the new television series, the family’s country seat (the town of Palma) is set in Ortigia, the most ancient part of the city of Siracusa on Sicily’s eastern coast, with the ducal palace as the Palazzo Beneventano del Bosco.

When this branch of the Filangieri family became extinct in the early twentieth century, this palazzo passed to one heir, while the Tomasi di Lampedusa family inherited the Palazzo Cutò in Bagheria, which they soon sold in 1923. Bagheria was a fashionable suburb of Palermo, to the east where the hills meet the sea. Several aristocratic villas were built here in the early eighteenth century, including this one by the Naselli family (whom we’ve encountered above), and by the Valguarnera family (also noted above), whose villa was used for the Salina Palace in the new Netflix series (and some of the gardens of the Villa Tasca, closer in to the city). The Palazzo Cutò still exists, but is not quite as glamourous to look at as the Villa Valguarnera—it was purchased by the municipality in 1987 and today houses a museum and library.

The 7th Prince died in 1831 and was succeeded by his son Giulio Fabrizio, who is the main model for ‘the Leopard’. His wife was indeed named Stella, and he did have numerous daughters, whose names mirror those in the book/films: Concetta, Carolina, Antonia, Chiara, Caterina and Maria Rosa. And although there was no handsome first cousin for one of these princesses to marry, two of his four sons did marry first cousins (one maternal and one paternal). The 8th Prince of Lampedusa was the last to actually own the island of Lampedusa, as it was forcibly sold to the King of Two Sicilies in 1843—the family had tried to re-populate the island in the 1760s, then during the Napoleonic Wars leased it out to the Order of Malta and to the British Navy, though neither of these really developed it either. After Sicily became part of Italy, Lampedusa was used as a penal colony; and in modern times the island has been in the news a lot due to it being so close to Africa and thus the first stop-off point for refugee boats heading towards Europe.

With the money he was given by the King in exchange for the island, Prince Giulio Fabrizio purchased a grander residence in Palermo, the former Palazzo Branciforte, built along the seafront on the old Spanish bastions (which were dismantled in the eighteenth century). Renamed the Palazzo Lampedusa alla Marina, half of this extensive palace complex was sold in 1862, but it was bought back in 1948 by the author of Il Gattopardo after the main Tomasi residence had been destroyed—he brought the family’s art collections and furnishings here, where they remain. Today it is known as the Palazzo Lanza-Tomasi, restored and revived in the later twentieth century by Gioacchino Lanza (see below), and forms part of the elegant waterfront of the city. For the new series, the Palazzo Comitini in Palermo stands in for this palace’s interiors, while the famous ballroom scene was shot in the Grand Plaza Hotel in Rome (whereas the 1960s Visconti movie used the Palazzo Valguarnera Gangi in Palermo, close to the main street of the city, Via Roma, and the famous square ‘Quattro Canti’, where several exterior scenes were filmed).

In January 1848, Sicily revolted once more against the Bourbons, and an autonomous parliament was again briefly created, with the 8th Prince again getting a peerage in its upper house, until this was brutally supressed in May 1849 by King Ferdinand II (and his general, notably a Filangieri prince, from the Neapolitan branch of the family), who earned his name ‘re bomba’ by ordering bombardment of the Sicilian city of Messina. This is the background for the events of the novel, when, just over a decade later, the liberals of Sicily rose up once more against the Bourbons and in support of an invasion in May 1860 of Giuseppe Garibaldi’s ‘Army of a Thousand’—the Redshirts. By the end of the year, Sicilians had voted to join the Kingdom of Sardinia, which, in the Spring was re-branded the Kingdom of Italy.

The ‘Leopard’ of Lampedusa lived another thirty-five years. Not much is known about his actual life, aside from his genuine passion for science, attested by numerous books on physics and astronomy in his library, and the observatory he built at the Villa Lampedusa in the hills north of Palermo (an area fashionable for aristocratic hunting lodges since the eighteenth century). He is portrayed as such in the novel and both adaptations (by the way, Don Fabrizio’s full titles in the book are Prince of Salina, Duke of Querceta, and Marquis of Donnafugata). The observatory is gone, but the villa has been beautifully restored recently as a luxury hotel.

His eldest son, Giuseppe, was 9th Prince of Lampedusa until 1908, and left several sons, the eldest of whom, another Giulio, was head of the family as the 10th Prince. His wife, Beatrice Mastrogiovanni-Tasca, was one of the co-heiresses of the Filangieri-Cutò estates as noted above. Her sister, Giulia, Countess Trigona, married to the Mayor of Palermo, and occupying the high-profile position in Italy as lady-in-waiting to the Queen, was brutally murdered by a scorned lover in a hotel in Rome in 1911, scandalising high society.

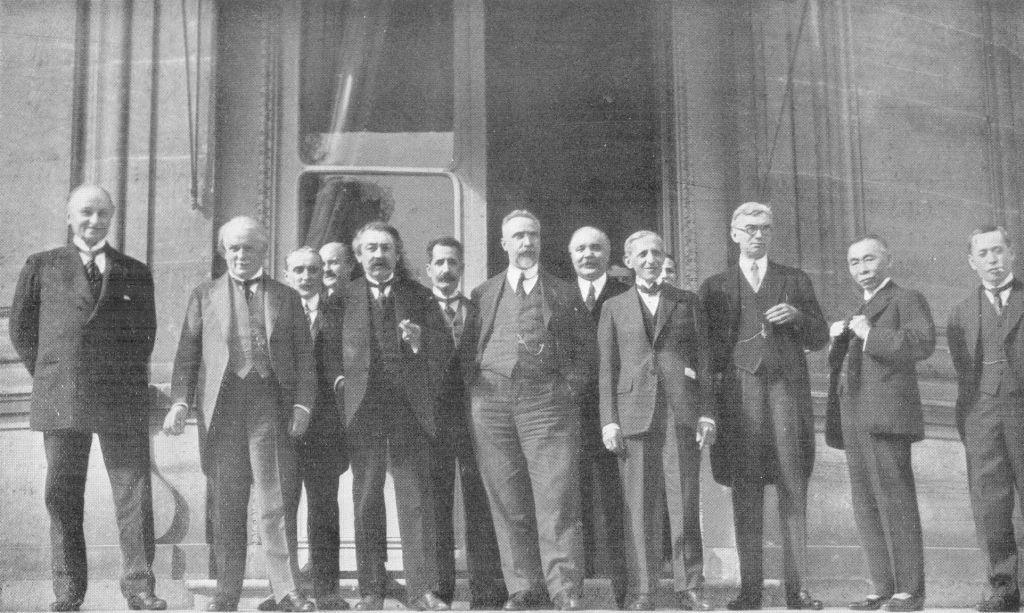

The 10th Prince of Lampedusa stayed out of the spotlight and tended to his agricultural affairs, still quite vast, in the south of Sicily. Though feudalism had ended in the 1840s, he still considered his primary duties to be the welfare of ‘his’ town of Palma di Montechiaro (its name formally changed in the 1860s) and its now ancient convent. It was his brother Pietro who made his name on the world stage. Don Pietro took the title Marchese della Torretta, from the family’s barony in the hills above Palermo. He trained as a diplomat and acted as Head of the Cabinet of the Minister of Foreign Affairs, 1910-14, then was sent as an envoy to Munich in 1915, then to Saint Petersburg in 1917 where he was promoted to full ambassador, a crucial position at such a pivotal time for Russia. In January 1919, Torretta was a member of the Italian delegation sent to the peace talks in Paris, then by the end of the year was appointed ambassador to the newly constituted Austrian Republic. He returned to Italy and was himself for a short time Minister of Foreign Affairs (1921-22). In 1921 he was named a Senator of the Kingdom of Italy, then sent abroad again, as Ambassador to Great Britain, 1922-27. He was pushed out of public affairs, however, by Mussolini at the end of the 1920s, for his liberal views, and only returned to politics after the war, when he acted as President of the Senate, 1945-46. As an old man, he briefly succeeded his nephew as the 12th Prince of Lampedusa, and died in 1962, the last of his family.

Back in 1920, Pietro Tomasi had married a retired soprano, Alice Barbi, who in her day had charmed the concert halls of Europe and built up a particular friendship with Brahms. From her first marriage to Baron Boris von Wolff-Stomersee, a Baltic German and official at the Russian court, she had a daughter, Alexandra (known as ‘Licy’). Born in Nice, but raised in St Petersburg, Licy inherited her father’s residence in rural Latvia, Schloss Stomersee: built in the 1830s, and rebuilt in French renaissance style in 1908; today known as Stāmeriena Palace. After a divorcing her first husband, she met and married in 1932 her step-father’s nephew, Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa. They lived together at Stomersee—one of the few Latvian aristocratic estates not nationalised in the 1920s—for a few years in the 1930s when Tomasi was eager to distance himself from Fascists in Italy. The palace later became a state-run agricultural college, abandoned after the fall of communism in the early 1990s, but recently bought, restored, and opened for tourism.

Giuseppe Tomasi, born in 1896, became 11th Prince of Lampedusa, 12th Duke of Palma, and Baron of Montechiaro and Torretta, Grandee of Spain, in 1934. He was a sort of ‘professional intellectual’, publishing a few short stories and pieces of literary criticism. He only wrote one novel, Il Gattopardo, which was rejected several times before it was published shortly after his death in 1957. Politically, he was a monarchist but with liberal leanings; critical of the Italian monarchy and the National Monarchist Party that attempted to restore it after the plebiscite of 1946, and interested in British liberals—whom he saw as less corrupt than his Sicilian countrymen. His wife lived mostly independently, pursuing a career as a psychoanalyst, and they had no children. In 1956, he adopted a member of his literary circle (and a distant cousin), Gioacchino Lanza Branciforte (from the noble house of Lanza encountered above, a son of the Count of Mazzarino), who had his own illustrious career as director of some of Italy’s leading musical establishments, including the opera house of San Carlo in Naples, and as a university professor in Palermo. He inherited the Palazzo Lampedusa alla Marina in 1957 and its collections, and alongside his wife, renovated it and turned it into a museum for the novelist and the Lampedusa family. By some accounts he is reckoned the 14th Duke of Palma (though titles were legally abolished alongside the Italian monarchy in 1946). He died in 2023, and was succeeded by his son Fabrizio Lanza Tomasi (b. 1961) as curator of the legacy of Il Gattopardo.

(images Wikimedia Commons)

One thought on “Il Gattopardo: The Real Leopard, Prince of Lampedusa”