I’ve just finished watching the last season of ‘My Brilliant Friend’ so my mind is focused on all things Neapolitan, and more troubling, about a world drenched in passion and violence. There were hundreds of wealthy aristocratic families in the Kingdom of Naples who were given princely titles—the highest honour, but without any sovereign status as in other parts of Europe—but none ended so suddenly and dramatically as the Gesualdo princes of Venosa, whose last member of the main line was both one of the most brilliant composers of the late Renaissance and a troubled soul who murdered his wife in a a fit of rage.

Carlo Gesualdo’s music is incredible, strange, beautiful, conflicted, with harmonies several centuries ahead of their time, tonal clashes and deep emotional sighs. Anyone who has sung one of his madrigals or church anthems will never forget the experience. Few probably know that he was a prince of ancient lineage, or indeed about his murderous past.

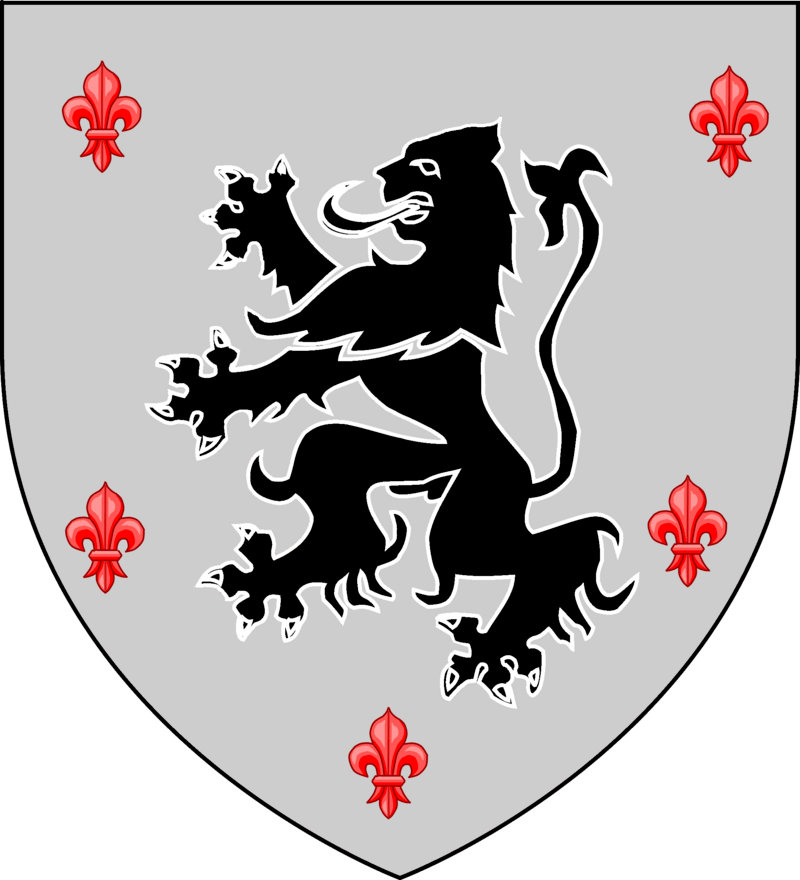

The Gesualdo family was in fact ancient, going back to the Norman conquest of the southern Italian lands of Sicily, Calabria, Apulia and Campania (the countryside around Naples) in the eleventh century. They became lords of Gesualdo in about 1140, counts of Conza in 1452 and princes of Venosa in 1561. The main line was extinguished in 1613 with the death of the composer-prince, but there was a cadet branch, the lords of Santo Stefano, who were created princes of Gesualdo in 1704, but died out again in 1770.

The Gesualdo lordship itself is even older. For four hundred years before the invasion of the Normans, another family ruled this important fief in Campania, in the province of Avellino—a region the ancients called Irpinia (the mountainous interior east of the City of Naples). They were likely descended from Germanic Lombard warriors who took over this region in the sixth and seventh centuries. The legendary founder, a knight called Giswald, was in the service if Romwald, Duke of Beneventum; he was captured by Byzantine troops besieging that city in 663, but he managed to trick his captors into warning his duke of their arrival, saving the city, but losing his life as a result. Romwald honoured his name by giving it to a hilltop castle held by his family, Italianised as Gesualdo. The castle we see today, with its four great circular towers dates from the ninth century—built in a period when the frontiers of Beneventum were again threatened, now by Saracens. It was later enlarged in the 1130s by its Norman rulers. For centuries it remained strategically placed to defend this border zone in struggles between France and Aragon over the Kingdom of Naples, but after the latter’s complete victory in the region in 1504, it lost its strategic value. It would eventually pass to another family in 1772, and was sacked by invading French troops in 1799. In the nineteenth century Gesualdo Castle was owned by the Caracciolo princely family then the Caccese, who restored it in the 1850s and made it liveable again. It was badly damaged in the terrible earthquake of 1980 that destroyed many towns in this region (see below), and has only within the last decade been re-opened to the public.

In the late 1030s, a group of adventurers arrived in southern Italy, descendants of the Viking warriors who had settled a corner of northwest France and renamed it Normandy. Several of these came from one family, the sons of Tancred, ruler of a small village of Hauteville in the Contentin, the peninsula that juts out from Normandy into the English Channel. The name Hauteville likely simply means ‘upper estate’, but the more romantic tale is that it took its name from an ancestor, the famous Viking Hialt, a companion of Rollo. The name was later Italianised to Altavilla. Of the many sons of Tancred, two of them, Guglielmo and Drogo, staked claims to rule parts of the old Byzantine province of Apulia (the heel of Italy’s boot). The more famous brothers were Robert Guiscard who turned these lands into the Duchy of Apulia and Calabria (the toe as well as the heel), and Roger, who conquered the island of Sicily from the Saracens in 1071. His son Roger II went one further and became the first king of Sicily in 1130. His cousin, Roger Borsa (Guiscard’s son), was Duke of Apulia and Calabria until 1111, and left behind at least two sons: one legitimate, Guglielmo II, who ruled as duke until 1127, and one illegitimate, also named Guglielmo, possibly by a lady of the ancient Gesualdo family. The link between Guglielmo d’Altavilla and the Norman Hautevilles is impossible to prove, and indeed there are several other families in the region who also claim illegitimate descent, like the Ruggieri (taking their name from Roger’s Italian name) or the Rossi, princes of Cerami.

Most of the fiefs mentioned in this post are located a little to the south of Ariano

What is known for certain is that by 1141 Guglielmo d’Altavilla was established in the lordship of Gesualdo and had married the heiress of the neighbouring lordship of Lucera. By the end of the century, the Barony of Gesualdo was one of the largest within the Kingdom of Sicily (which now included both the island and the mainland), with over thirty lordships spread over three provinces. The power of lords like those at Gesualdo in Campania was especially strong given their distance from the royal court in Palermo. Guglielmo’s sons held the highest positions in the royal government and military: Elia (Italian for Elijah) was Justiciar and Constable of the Kingdom in 1183, while Aristolfo was named commander of the Sicilian armies in the Second and Third Crusades (1147 and 1189).

The last legitimate Norman king of Sicily died in 1189, and a power struggle between a legitimate daughter and an illegitimate son (also named Tancred) resulted in the takeover by the Holy Roman Emperor Henry VI from the Hohenstaufen dynasty. In the years that followed, the landholdings of the Altavilla family—who started to use the surname Gesualdo at this point, probably wisely distancing themselves from the disgraced former ruling dynasty—were significantly reduced. The family soon recovered their prominent position in royal government by joining forces with a new invader: Charles of Anjou, who became King of Sicily in 1266. Elia II, Lord of Gesualdo, was named Marshal of Sicily in 1266, and Justiciar of Calabria in 1269. His son Nicola I also supported the Angevins, especially after they were chased from Sicily in the Sicilian Vespers of 1282, and was named Captain-General of the City of Naples in 1289. In 1299 he was confirmed as Baron of Gesualdo. His nephew Nicola II was then Vicar-General of the Kingdom for King Robert of Anjou, while his son Matteo served as a chamberlain to this king and to his granddaughter Queen Giovanna I. In 1344, his brother Ruggero was elected Bishop of Nusco, whose see was in the same area as their landholdings in Campania, while the youngest, Francesco, married the heiress of the lordship of Bisaccia (on the eastern edges of Campania) and left many descendants.

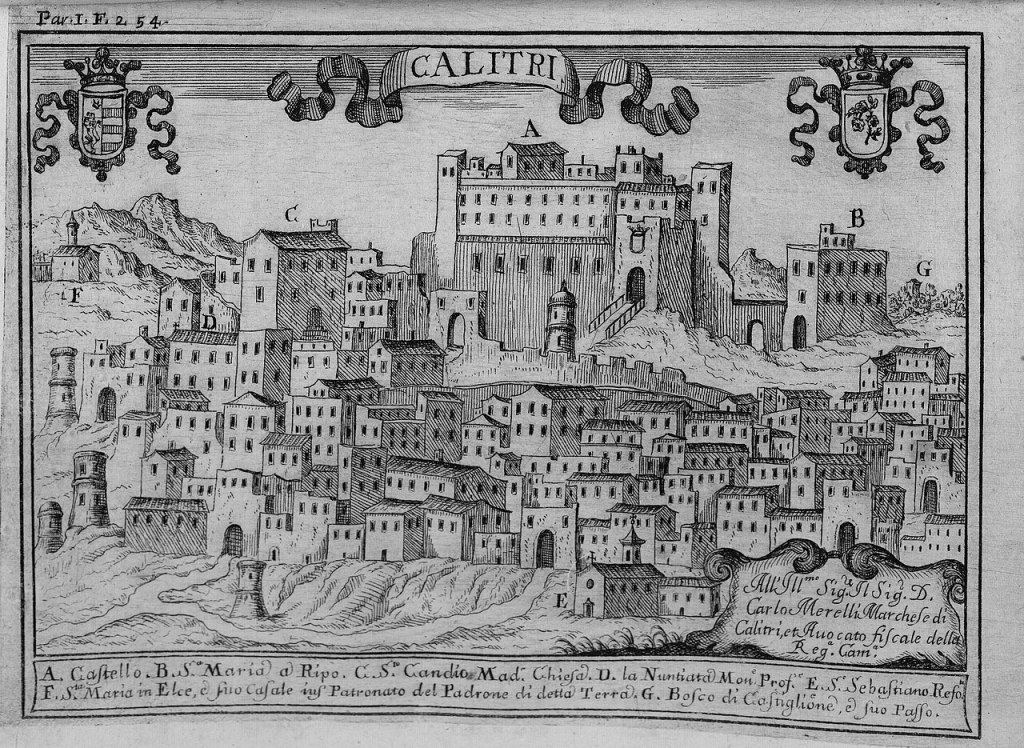

In the next generation, Luigi I, Lord of Gesualdo, continued service to the Angevins, as Major Domo to King Charles III in the 1380s. In this century their chief residence became a fine castle, Calitri, perched atop a hill in close proximity to their other fiefs in this region. Calitri was built before the twelfth century and was surrounded by ancient houses built into the hilltop itself. The Gesualdos developed it into a sumptuous lordly residence. Like we’ve seen so far several times, it was destroyed and rebuilt several times by earthquakes over the centuries, and remains heavily damaged from the quake of 1980.

In a similar manner, the House of Anjou came crashing down in 1435, and families like the Gesualdos scrambled for power in the ensuing conflict between French and Spanish contenders for the throne. Either Luigi II or Sansone II was created count of Conza, another one of the family’s lordships in Campania. The 4th Count, Fabrizio, was named a Grandee of Spain in 1536, as a sign of his family’s now firm loyalty to the new dynasty, the Habsburgs. The ancient Roman town of Compsa sat on the strategic pass towards Salerno and the coast. It had been the seat of a bishop since the eighth century, raised to an archbishopric in the eleventh. The family owned a castle nearby called Castelnuovo di Conza. Frequent earthquakes in this region meant that by the sixteenth century, the archbishops more usually resided in Sant’Andrea di Conza—and this was one of the worst hit spots in the earthquake of 1980s. Conza was entirely destroyed and the archbishopric permanently moved to Sant’Angelo dei Lombardi with a brand new cathedral.

Several Gesualdos held this see, four archbishops of Conza in a row (almost) between 1517 and 1608: Camillo was first, for eighteen years, followed by his nephew Troaino for four. After a gap of just over twenty years, his nephew, Alfonso, was appointed. At the time of his appointment, Alfonso Gesualdo was also a cardinal, one of the youngest at only 21. He had a long and illustrious career in the Church—as candidate for the papal throne several times, and ultimately Dean of the College of Cardinals—and was appointed Archbishop of Naples in 1596, reigning there until his death in 1603.

Cardinal Gesualdo had resigned the see of Conza to a cousin from a junior branch, Scipione Gesualdo, in 1584, who ruled the diocese until his death in 1608. Another cousin, Ascanio, took over as head of the Gesualdos’ ecclesiastical arm when he was appointed Archbishop of Bari in 1613 and titular Patriarch of Constantinople in 1618 during his posting in Prague as Nuncio to the Holy Roman Emperor.

The uncle of the Cardinal, Luigi IV, Count of Conza, was raised a rung in the aristocratic hierarchy when he was created Prince of Venosa in 1561. He had acquired more estates and wealth through his marriage to Isabella Ferrillo, heiress of the barony of Montefredane and large sums of cash, with which he purchased the city of Venosa. He was an efficient financial manager and became one of the richest men in the Kingdom. He was also an advisor to the government of Philip II, and a patron of poets and musicians in Naples.

Venosa was a very ancient city; the Romans called it Venusia, clearly named for the Goddess of Love. The legend was that Diomedes, King of Argos, founded it after the fall of Troy and named it as an apology to Venus for having offended her in thinking Helen was so beautiful. It was strategically located, on the border between Apulia and Lucania on the Via Appia (the road from Rome to Apulia), in a province now called Basilicata. Its other claim to fame in ancient times was as the birthplace of the poet Horace. It was one of the early bases of the Altavilla dynasty, who buried some of their lords there; the Emperor Frederick II built a new castle in the early thirteenth century, while Charles of Anjou refortified it, and set it up as an autonomous county for his son Robert a few decades later. The County of Venosa passed to the powerful Orsini family in 1453, then by marriage to the Del Balzo, who built another new castle there in 1470—square with four massive cylindrical towers. The Gesualdo family only held it from 1561 to 1613. Since then it has been the seat of the Academia dei Rinascenti, and since 1991 it has housed a new National Museum of Venosa.

In a dramatic shift away from the focus on wealth of his father, Fabrizio Gesualdo, 2nd Prince of Venosa, was quite pious. He stood out amongst other Neapolitan nobles, and even more so through the company he kept, as a friend of his brother-in-law Cardinal Carlo Borromeo, Archbishop of Milan. As part of the marriage settlements for Geronima Borromeo, the pope, Pius IV (the bride’s uncle), the principality of Venosa was confirmed for the family, and Fabrizio’s brother Alfonso was given his cardinal’s cap (see above). Cardinal Borromeo was one of the leaders of the Catholic Church’s internal reforms of the 1560s-70s—he would be canonised in 1610.

The product of this union of wealth and piety was Carlo Gesualdo, 3rd Prince of Venosa and composer of sublime music. He was initially the second son, and was sent to Rome to be raised by his two cardinal uncles for an elevated career in the Church. Already he displayed an interest in music, and was certainly well placed in Rome to learn from the best. He learned to play many instruments, including the lute and the harpsichord. But his older brother Luigi died from a horse-riding accident in 1584, making Carlo the heir. Two years later he married Maria d’Avalos, daughter of the Prince of Montesarchio (who was also his first cousin). He spent much of his time in Naples residing in the palace of relatives, the Palazzo San Severo (aka di Sangro). One day in October 1590 he arrived there to find his wife in bed with Fabrizio Carafa, Duke of Andria, and he killed them both on the spot. An official investigation concluded that he had committed no crime.

A few years later he travelled north, to the court of the Duke of Ferrara, at that time one of the leading centres of music, particularly the style of secular song known as the madrigal. He married a cousin of the Duke, Leonora d’Este, and spent several years in her hometown learning the craft of composing. When they eventually returned south to the castles of Gesualdo and Venosa—his father having died in 1593, Carlo was now the prince—his wife complained of abuse but was unsuccessful in obtaining a divorce. By this time, Gesualdo’s story of his first wife’s murder was already sensational and the inspiration for poets and novelists (and indeed, when interest in his music was revived in the 1920s, so too was interest in the story, inspiring a large number of operas—though I can’t say any of them ever reached number one). It doesn’t hurt that the palace in Naples was named ‘di Sangro’ (‘bloody’, though just by coincidence).

The Prince began publishing music himself as well, adding five more books of madrigals on top of the one he had published in Ferrara. He became a recluse and his music more contorted and expressive, particularly his religious anthems and music meant to accompany the Tenebrae services in the days of mourning preceding Easter. Was it intense remorse for his actions, or the onset of mental illness? Guilt-driven depression may have been intensified by the death of his only son Emanuele, in August 1613 in a hunting accident, and he followed his son to the grave a few weeks later in September.

All that was left of this branch of the Gesualdo family were several women: the composer’s widow, Leonora, who lived until 1637, his son’s widow, Maria Polyxena von Fürstenberg (who remarried, but not until many years later), and her two daughters. While the younger, Eleonora, became a nun in Naples, the elder, Isabella, became Princess of Venosa, Countess of Conza, and Lady of Gesualdo. She took these properties by marriage into the family of Ludovisi—a Roman princely family I have written about here. They retained the title Prince of Venosa into the present.

Meanwhile there was a cadet branch of the family. Back in the fourteenth century, a younger son received the lordship of Pescopagano, across the frontier from Campania in Basilicata (though not far). Like most towns in this region, it was built around a bold castle atop a rocky hill.

This branch gained other lordships in the region, intermarried with other noble Neapolitan families (Carafa, del Balzo, Caracciolo), and supplied sons for the local abbeys and bishoprics (including two of the archbishops looked at above). In the sixteenth century, Fabio Gesualdo di Pescopagano purchased another fief, Santo Stefano, also in Avellino province. The family moved into the ‘palazzo baronale’, which is today the town hall.

Following the extinction of the senior line, this junior line of Gesualdo di Santo Stefano purchased some of the family fiefs, including in the castle of Gesualdo itself. This was then raised to the rank of a principality in 1704 by the new king of Naples, Philip V, of the House of Bourbon. His rule was short in Naples, however, due to the War of Spanish Succession, and the title would need to be re-confirmed once the Bourbons returned to power in 1734. By this point, the 1st Prince (Domenico) was dead, and his son (Nicola) had become head of the house—he had been created Marchese of Santo Stefano in 1711, I assume by the Austrians who ruled in Naples after Philip V had been driven out. He died in 1738, and his son then ruled their tiny principality for another 32 years before he too died, with no heirs except a few sisters who had taken vows as nuns so couldn’t inherit anything. I have not found any images of these Gesualdo princes or really any biographical information about their lives.

Though the fief of Gesualdo itself was sold in 1772 to the Caracciolo family, the princely title was inherited by a first cousin, Oderisio di Sangro—from the same family who owned the palazzo of that name we’ve seen before in Naples—who much earlier (1720) had purchased the principality of Fondi (closer to Rome) from the Mansfeld family. This family continues to exist, and its head today, Riccardo di Sangro (b. 1959), uses the title 15th Prince of Gesualdo.

(images Wikimedia Commons)