An interesting illustrated poster was published in about 1715 for distribution to the people of Great Britain that celebrated the health and vitality of their new royal family: the Hanoverians. At the top is the prosperous looking King George I, a former war hero in Europe and a symbol of the ongoing stability of the Protestant faith in England. Below him are the figures of his son and daughter-in-law, the Prince and Princess of Wales, and their already growing nursery of royal children, Prince Frederick and his sisters, Anne, Amelia and Caroline. A prosperous eighteenth century beckoned for the British people. It was a very ‘family values’ type item of propaganda. But there’s a curious omission: the King has no wife, alive or dead. It’s as if he generated his dynasty completely on his own.

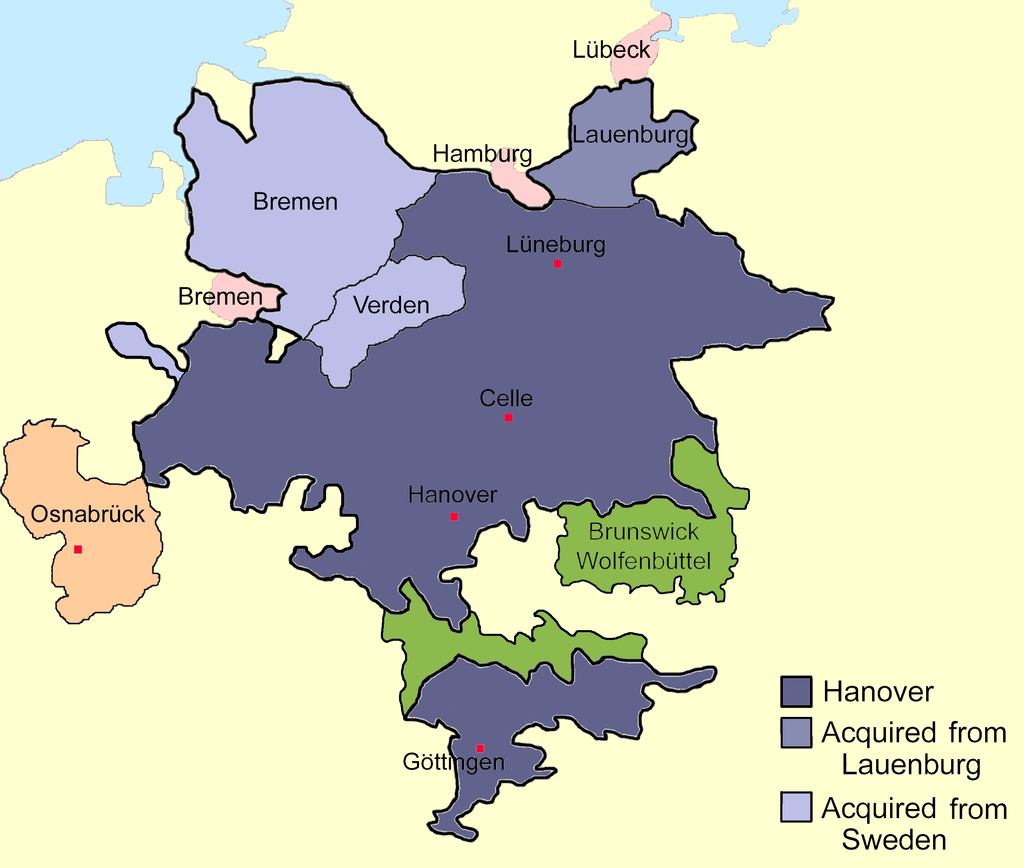

Sophia Dorothea of Brunswick-Lüneburg was, at least in theory, the queen-consort of Great Britain in 1715. Yet she never left Germany, and lived in confinement for the entirety of her husband’s reign. Her story is fascinating, and not well known, but before we tell it, we need to look at the dynasty of dukes and princes she represents. It is in fact the same dynasty as her husband’s and they were first cousins. The House of Brunswick-Lüneburg is just another name for the House of Hanover. It is one of the oldest princely houses in all of Europe, with roots stretching back to the ninth century. Known initially as the House of Welf (or Guelph in English), its early history has already been traced in a previous blog post, in the context of another British queen-consort, Caroline of Brunswick. Queen Caroline’s branch was based in Wolfenbüttel, while Sophia Dorothea’s family were based further north in Lüneburg. These two halves of the overall Duchy of Brunswick-Lüneburg, created in 1235, had been divided, subdivided, re-combined and re-divided several times in the centuries that followed. This post will focus on the line of Lüneburg that was founded from a division of 1428, and then another division in 1634. After 1692, though Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel was the senior line, its dukes were eclipsed by the rise of the Hanoverians, first as electors of Hanover, then (from 1714) as kings of Great Britain and Ireland. The senior line became extinct in 1884 and in theory at least the two branches were united once more in the person of Queen Victoria’s cousin, the Duke of Cumberland, as we’ll see at the end of this post.

As seen in the previous blog, the main seat of the medieval House of Welf was in Brunswick (Braunschweig in German), but had a second seat much further north, on the great North German plain, Lüneburg, a city wealthy in trade links and salt deposits. The first major division was made in 1269, with the senior line in Lüneburg and junior lines being established in Wolfenbüttel, Grubenhagen, Göttingen and Calenberg. Officially, the imperial fief of Brunswick-Lüneburg remained undivided, so all princes from all branches had the potentiality to succeed, and individually the smaller units were referred to as ‘principalities’ within the duchy. The first line of Lüneburg came to a violent end in 1370, and following a devastating War of Lüneburg Succession, this branch of the dynasty moved its headquarters further south, to Celle.

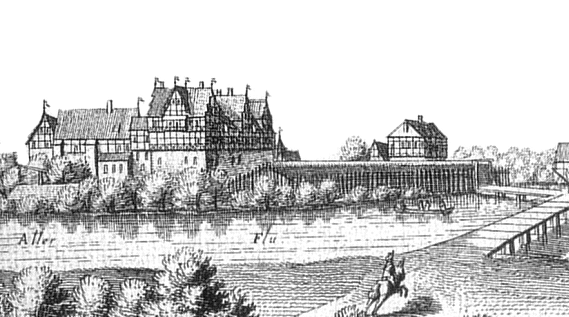

The Castle of Celle was built on the river Aller, a tributary of the Weser that flows across the North German Plain, through Bremen and into the North Sea. Other tributaries include the Oker (which flows through both Brunswick and Wolfenbüttel) and the Leine (which joins Göttingen to Hanover). So most of the family’s territories—aside from Lüneburg itself—were joined by a network of rivers. The castle at Celle was very ancient, probably a tenth-century fortress guarding the river crossing. But it wasn’t a proper residential castle until the 1370s. It still today has the basic footprint of a rectangular keep with four huge corner towers, all on a moated island, but today’s appearance is from the later fifteenth century, the so-called ‘Weser Renaissance Style’. Remodelled in the 1670s by Duke Georg Wilhelm (below), with Italian influences, grand baroque state rooms, a theatre (one of the few remaining in northern Germany today) and French gardens, it was then underused in the eighteenth century until it became the prison for the disgraced Caroline Matilda of Hanover, Queen of Denmark, between 1772 and 1775. Celle was later used as a summer residence for the Hanoverian royal family of the nineteenth century, who expanded its landscape gardens.

One of the trends of the House of Brunswick in the Middle Ages was a desire to expand westward across Westphalia by absorbing smaller imperial counties, like Wölpe in 1302, Hoya in1582 and Diepholz in 1585. They also expanded their influence by placing sons in the key neighbouring bishoprics of Hildesheim, Verden and Bremen, and after the Reformation gradually absorbed these territories into their domains as well (basically creating what is today called the state of Lower Saxony). A new division of the entire House of Brunswick occurred in 1428, when Bernhard kept Lüneburg, Celle and other northern territories for himself, and gave Wolfenbüttel and other southern lands to his younger brother Wilhelm.

Bernard died in 1434 and was succeeded by his sons ruling jointly, Otto IV the Lame, who died in 1446, and Frederick II the Pious. The brothers built the Castle of Celle into a proper princely residence. Frederick had an exceptionally long reign, even with a pause in the middle when he resigned to enter a Franciscan monastery he had built in Celle in 1457. His eldest son, Bernard II, had first been Bishop of Hildesheim, but resigned to take up his father’s position, with his brother Otto V as co-duke. Both sons were dead by 1471, so Frederick the Pious reigned once more until his death in 1478

Otto V’s young son Henry succeeded, age 10, under the regency of his mother, Anne of Nassau. He was pious like his grandfather, but got in trouble as an adult when he refused to support the election of Charles of Burgundy as Emperor Charles V in 1519. He was forced to abandon Germany and took refuge at the French court. Seeing his sons embrace the early phases of the Protestant Reformation, he attempted to return in 1527 to block the spread of heresy in Brunswick. He was pushed out and died in exile in 1532.

These sons, Otto, Ernst and Franz, all studied at the University of Wittenberg, the seat of their mother’s brother, the Elector of Saxony, the protector of Martin Luther. Otto and Ernst were given the duchy of Bruswick-Lüneburg by the Emperor to rule jointly in 1520, and they introduced many of the Lutheran reform ideas. Otto went further and married for love rather than duty in 1527, so resigned his rule and received instead the barony of Harburg. His children were to be reckoned as barons, not princes.

The line of Brunswick-Harburg was thus based in the castle of Harburg built by the counts of Stade in the 1130s on one of the branches of the Elbe south of the city of Hamburg. Acquired by the House of Brunswick in the 1250s, it remained a secondary castle until it became the seat of this separate branch in 1527. Otto of Harburg’s son Otto II took over in 1549 and was restored to his rank as a Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg in 1560. He turned Harburg into a princely residence. After it returned to the main line in the mid-seventeenth century it was transformed again into a fortress. Much of this was pulled down in the nineteenth century, and today Harburg has been amalgamated into the city of Hamburg.

Otto II died in 1603, leaving four sons. The eldest, Otto Henry, had died in 1591, and had married unequally, so his son Charles, a Spanish governor in the Low Countries, could not inherit. The next son, John Frederick, declined the succession, and Christopher soon died, so William Augustus and Otto III ruled together until their deaths in 1642 and 1641, respectively. The elder duke of Brunswick-Harburg was a scholar, and travelled all over Central Europe and Scandinavia. When the lands of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel were redistributed in 1634 (see below), he was given the County of Hoya, but when he himself died, unmarried, this, plus his possessions in Harburg were re-divided between the lines of Celle and Wolfenbüttel.

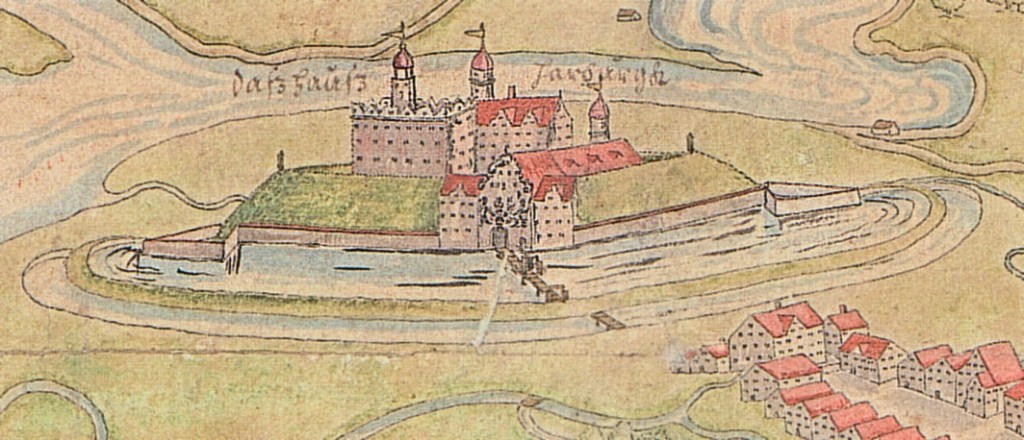

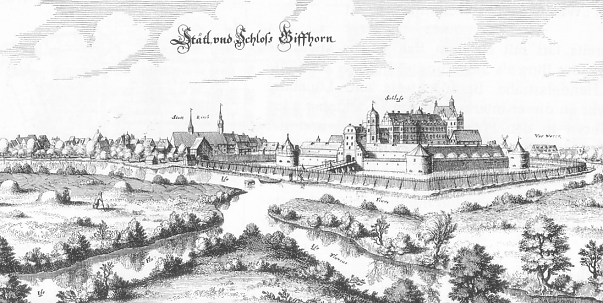

Meanwhile, another division had been made between the sons of Duke Henry, in 1539, with the creation of an apanage of Gifhorn for the youngest son, Franz. The castle at Gifhorn, only a princely capital for ten years, is one of the best preserved in the region, southeast of Celle, upriver on the Aller. Franz built a new residence here on the site of a much older castle. Heavily fortified, with ramparts, a wide moat and four corner bastion towers, it remained a fortification for the dynasty until the 1790s. Duke Franz was also an ardent supporter of the Protestant movement; the chapel he built here in 1547 was the first built specifically for Reformed worship in Germany. But the Duke died in 1549 and left only daughters, so Brunswick-Gifhorn did not spawn a separate branch.

Franz’s elder brother, Ernst the Confessor, thus ruled Lüneburg-Celle alone. He introduced Lutheran preachers all over his domains in the 1530s and secularised monasteries. He convinced the north German cities of Hamburg and Bremen to join the Schmalkaldic League, defending their church against the forces of the Catholic Emperor, and by the time of his death in 1546 was the most influential prince in the northern parts of the Empire.

Ernst left four underage sons, Franz, Frederick, Henry and William, who were governed by their mother, Sophia of Mecklenburg, for the first ten years. Frederick died young, followed by Franz in 1559, leaving Henry and William to govern together. The brothers quarrelled and Henry gave up the bulk of the Brunswick-Lüneburg lands to William, agreeing instead that he would inherit the lands of the Wolfenbüttel branch which was heading for extinction already in the 1560s. As we can see in the Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel post, that gamble paid off, though not until 1634, and a new line of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel was created which persisted until the 1880s.

Duke William alone took over the Lüneburg lands and the family seat at Celle from 1569. In 1561 he had made an excellent marriage in Dorothea of Denmark, daughter of Christian III. She began to take charge of his estates in the 1580s as he slipped into mental illness, and after he died in 1592, she governed on behalf of their many sons: of fifteen children total, six boys survived to adulthood. The eldest, Ernest II, became head of this branch of the family, and the year before he died in 1611, convinced his siblings to agree to a new family pact that stipulated that the Brunswick-Lüneburg lands were henceforth indivisible—no more partitions—which was formally confirmed as law by Emperor Mathias.

The next two brothers were both ecclesiastics, but in the confusing times of the late sixteenth century governed their bishoprics either as elected Catholic bishops or as Lutheran ‘administrators’ of their sees: Christian in Minden and Augustus in Ratzeburg (on the south-western and north-eastern borders of Lüneburg respectively). Christian also took the lead in governing Lüneburg after 1611 and successfully added the principality of Grubenhagen to the south. In 1629, he renounced his ecclesiastical position and stepped aside as Sweden occupied the prince-bishopric of Minden—it was secularised and given to Brandenburg in the settlement of Westphalia in 1648. By that point, Christian had died, as had Augustus, who left several children by his ‘concubine’—these took the surname ‘von Lüneburg’ and continued on into the 1960s. The fourth son, Frederick, also held church offices, notably Provost of Bremen Cathedral, and died at the end of that eventful year 1648.

Meanwhile the youngest brother, Prince George, was lord of Calenberg and Göttingen from 1635, adding these southern territories to the Lüneburg branch of the family, whose lands now stretched from the Elbe River in the north to the Harz Mountains in the south. At first he lived in the Harz at the mighty hilltop castle of Herzberg (part of the Grubenhagen estates), where most of his children were born, but in 1636 relocated his seat—while his older brothers still governed from Celle—to the town of Hanover on the river Leine. Here he built a new residence, the Leine Castle or Leineschloss.

Hanover—whose name may derive from hohen Ufer, the ‘high riverbank’—developed as a town in the thirteenth century, at a crossroads linking trade routes from the Hanseatic cities of the north to the hilly interior to the south. Duke George’s new residence on the Leine had been a Franciscan friary since the fourteenth century. Secularised in 1533 when the area became Lutheran, the new castle incorporated the old monastery church as its chapel. Enlarged later in the later seventeenth century by Duke Ernst August, notably with the addition of a theatre, the Leineschloss was the birthplace of the future George I of Great Britain in 1660. It became a royal palace from 1814 and was rebuilt and expanded over the next two decades in a neoclassical style under the guidance of the Duke of Cambridge, viceroy of Hanover. It was then the main royal residence of the kings of Hanover after the dynastic separation from Great Britain in 1837, until it was taken over by occupying Prussian administrators in 1866. The Leineschloss was almost completely destroyed by aerial raids in World War II, and rebuilt in 1957-62, though with a more modern look. Today it is the seat of the parliament for the state of Lower Saxony.

Duke George of Brunswick-Calenberg died in 1641. His eldest son Christian Ludwig succeeded to all of the family lands in 1648 with the death of his uncle Frederick, but as was firm family tradition, shared rule with his many brothers. He resided at Celle and gave Calenberg to the second son, Georg Wilhelm (I’ll shift to German spellings now). Meanwhile their sister Sophie Amalie became Queen of Denmark and Norway in 1648, having married the son of Christian IV in 1643. Her husband Frederick III had been (when he was the second son, not the heir) the Lutheran administrator of Verden and Bremen during the Thirty Years War—we will see these two territories later added to the patrimony of the House of Hanover.

Christian Ludwig died in 1665. Before he did though, the brothers had made a pact, 1658, agreeing that none would marry except the youngest, Ernst August. In 1665, the second brother, Georg Wilhelm, became Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg, and passed the secondary principality, Calenberg, to the third brother Johann Friedrich, keeping only Celle for himself. He did this because he was about to break the brotherly pact by marrying: a Huguenot noblewoman from Poitou, Eléonore Desmier d’Olbreuse. The marriage was deemed unequal, and their one child, Sophia Dorothea, born 1666, was barred from claiming full rights as a member of the House of Brunswick. In 1674 the Emperor raised Eléonore and her daughter to the rank of Countess of Harburg and Wilhelmsburg.

Harburg refers to the Brunswick residence outside Hamburg as above. The latter name was a curiosity: three small islands in the river Elbe near Harburg acquired by Georg Wilhelm in 1672 and renamed for him. He connected the islets together using dams, and gradually the area was developed as part of the port of Hamburg. Harburg-Wilhelmsburg formed one administrative unit from the 1920s and was annexed to the city of Hamburg in 1937. It even had a small moated castle, dating from about 1500, today a ruin.

George William lived for many years at Celle, and served as a military commander as a loyal supporter of the Emperor in Vienna—while in contrast, his Catholic brother Johann Friedrich supported France in its wars of the 1670s. He had turned out to be one of the most distinctive of the Brunswick brothers: a Francophile and a Catholic. Travelling in Italy as a young man in the 1650s, he had encountered the intense personal piety of the Catholic Reformation in Rome and renounced his Lutheran faith in about 1651.

In the 1660s, while Georg Wilhelm remained in Celle, Johann Friedrich settled into his share of the duchy, Calenberg, making Hanover his residence. Here he imported Italian architects to design new baroque churches, and, inspired by developments he’d seen in garden design in France, he decided to build a French garden of his own, Herrenhausen, a short distance outside the city. This was built in a floodplain of the Leine, the site of a small manor house built in the 1640s and now enlarged as a summer palace. Herrenhausen eventually was connected to the city of Hanover by a one-mile long Allee and included several distinct gardens (the Great Garden, the Hill Garden, and the George and Welf gardens). Much of it was developed by the Electress Sophia (below), and she, her husband and son are buried here. Herrenhausen was still owned by the House of Hanover in the 1940s, badly bombed in 1943 and rebuilt only in 2010-13, reopening in time for the fantastic exhibitions celebrating the three-hundredth anniversary of the Hanoverian accession to the British throne—during which time I was fortunate to visit this magical place.

Duke Johann Friedrich was not meant to marry, according to the pact agreed by the brothers in the 1650s, but he did. In 1668 he married Benedicta Henrietta of the Palatinate, daughter of one of the sons of the ‘Winter Queen’ (Elizabeth of Bohemia) who had, like himself, renounced Protestantism. Her sister was the Princess of Condé, first princess of the blood in France, so this marriage made the dukes of Brunswick nervous. Happily for them, the couple had only daughters, so they could not inherit the Welf properties, but two of the three made excellent marriages: one became Duchess of Modena, and the other, Wilhelmine Amalia, became Holy Roman Empress as wife of Joseph I. Johann Friedrich’s other long-term impact was the hiring in 1676 of a new librarian at Herrenhausen, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, who also became a trusted ducal counsellor, and stayed in the family’s employment for the next forty years.

When Johann Friedrich died in 1679, he passed the principality of Calenberg and the residences in Hanover to the youngest brother, Ernst August. Ernst had been chosen to marry the princess from the Palatinate, Sophie, whom none of his older brothers seemed to want, in 1658; he then was selected to act as Prince-Bishop of Osnabrück in 1662. His marriage was no obstacle here, since Osnabrück now had a very strange constitution: since 1648, it was agreed that the Catholic canons of the cathedral would elect their own bishop, and when he died, the territory would be governed by a Lutheran member of the House of Brunswick—and then would return to the Catholics again when he died, on and on in alternation. Ernst and Sophie moved into the bishop’s residence outside the town, Iburg Castle, then after 1667 began construction of a new palace in the city itself.

Iburg Castle, about 16 km south of Osnabrück, had ancient roots, with a castle built here as early as the eight century by the local Saxon kings. A new castle was constructed in the eleventh century by Bishop Benno—who gave his name to the central tower, the Bennoturm—as well as a Benedictine monastery. Ernst August added a Protestant chapel in the castle, leaving the earlier Catholic one too.

The Osnabrück residence built by Ernst August remained the main seat of the prince-bishops until the principality was secularised and incorporated into the Kingdom of Hanover in 1803. The palace is still lovely today and it serves as the main buildings for the University of Osnabrück.

Now ruler of all of the Brunswick-Lüneburg territories except Celle (still occupied by Georg Wilhelm), Ernst August moved his residence to the Leineschloss in Hanover. He began the process of enhancing his family’s position within the Holy Roman Empire—serving as a commander in the armies of Emperor Leopold I in the defence of Vienna against the Turks in 1683, then in the battles to reclaim the Hungarian plain, he struck a deal in return that would turn his patchwork of duchies into a unified state which would be erected into the ninth electorate of the Empire. There had been seven electors since the fourteenth century, but after 1648 there were eight, since Bavaria and the Palatinate split the ancient Wittelsbach vote. In anticipation of his family’s elevation, Ernst declared in 1683 that from henceforth, his family would be ruled by primogeniture and the centuries-old practice of dividing the duchy up between sons would cease. In 1692, the Emperor held up his end of the bargain, and Brunswick-Lüneburg was named an electorate, though it is better known as Hanover. The new elector was also given an official ceremonial role within the Empire, as ‘arch-bannerer’, with ceremonial duties at imperial coronations and funerals (this office was later exchanged in 1710 for ‘arch-treasurer’).

By this point, the heir, Georg Ludwig, was married. He had initially rejected the idea of marrying his cousin, Sophia Dorothea, as someone not fully princely due to her parents’ unorthodox marriage. But in 1675, Duke Georg Wilhelm decided to secure his daughter’s future by declaring that his marriage to Eléonore d’Olbreuse was fully valid, not morganatic, and that she and her daughter were both intitled to be styled duchess of Brunswick. He even staged another wedding ceremony at Celle in 1676 to be clear: it was not attended by his family. Duchess Eléonore even became pregnant in 1679 and there were fears she would have a son, throwing all of the Hanoverian plans into disarray. The child did not live, but Ernst August was thus convinced that his son would marry Sophia Dorothea. They married in November 1682, and although they had two children right away they soon loathed each other and lived apart.

Then in the 1690s, the domestic harmony of the House of Hanover fell apart. All the sons of Ernst August and Sophie were warriors: Georg Ludwig and his brother Friedrich August also fought at the siege of Vienna 1683. But after the latter was killed in battle in Transylvania in 1691, the next sons in line, Maximilian Wilhelm and Christian Heinrich, realised that the new primogeniture rules meant they would not receive a portion of the duchy to rule when their father died. They plotted against him, were arrested and exiled. Both became imperial commanders and converted to Catholicism. Christian Heinrich was killed in 1703 near Ulm, but Maximilian Wilhelm lived on in Vienna until 1726.

This rebellion averted, another arose in 1694, in the person of the heir’s wife, Sophia Dorothea. Though her husband of course had a mistress by the early 1690s (his wife’s lady in waiting, Melusine von der Schulenberg), when Sophia Dorothea herself fell in love, with Philipp, Count von Königsmarck, a general in the army of the Elector of Saxony, it was unacceptable. In 1694 it became public knowledge at court, and her husband threatened her with imprisonment or violence. She appealed to her parents in Celle, and got no support, so planned to escape with Königsmarck to Dresden. On the night of 11 July, the Count suddenly disappeared—and no one has ever discovered what happened: was he thrown into the Leine? It caused an international incident involving Saxony, Poland, Austria, France… Georg Ludwig demanded a divorce, which was granted by the end of 1694. Sophia Dorothea was confined to Ahlden House, a large moated manor house on the Lüneburg Heath west of Celle. Today it is an antiques auction house. She was sometimes called the ‘Princess of Ahlden’ but it was an empty title as she was confined here for the rest of her life (she died in 1726).

The first Elector of Hanover, Ernst August, died in 1698. Shortly after this, his widow, Electress Sophie, was named as heir to the thrones of England, Scotland and Ireland by the Act of Settlement, 1701. She very nearly succeeded her cousin, Queen Anne, but died at her beloved Herrenhausen only two months short, in the summer of 1714. The history of the House of Hanover now became the history of the royal house of Great Britain, so outside the scope of this blog site. Georg Ludwig, Elector of Hanover, became George I, king of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and his family governed these islands until the death of Queen Victoria in 1901.

Links with Germany certainly continued: King’s George’s sister, Sophie Charlotte, married the Elector of Brandenburg and became the first Queen of Prussia when her husband’s status was elevated in 1701 (Charlottenburg Palace in Berlin is named for her). The youngest brother, Ernst August, was selected to fill the family’s post as Prince-Bishop of Osnabrück in 1715. In Britain he was also created Duke of York and Albany; his elder brother, Maximilian Wilhelm, was given nothing, and as a Catholic, was excluded from the line of succession. A later Hanoverian prince, Frederick (also duke of York), occupied this curious hybrid episcopal see of Osnabrück from 1764; he would be the last, as the prince-bishopric was dissolved in 1803.

Osnabrück was not the only family tie remaining in this region. The Electorate was now one unit, giving the Elector (aka the King of Great Britain and Ireland) a vote in the Imperial Diet. But after 1715 there were also several other adjacent territories that continued to have elements of separate government and gave additional votes to the Elector: the counties of Hoya and Diepholz, and now the duchies of Bremen and Verden, secularised former bishoprics governed by Sweden after the Thirty Years War and now purchased by Hanover. George I also added the final domains of Celle to Hanover after the death of his uncle and father-in-law. Georg Wilhelm had also occupied the neighbouring Duchy of Saxe-Lauenburg, whose ancient line of dukes had died out in 1689 (this duchy, one of the Empire’s oldest, will have its own blog post); so it too passed to the Elector of Hanover as a separate political entity (and yet another vote in the Diet), though not confirmed by the Emperor until 1729. Some of these territories had direct votes like Bremen and Verden, while others were entitled just to participate in a collective vote of the council of counts of Westphalia, like Hoya and Diepholz, and the county of Spiegelberg (south of Hanover, a county since the 1060s, part of Brunswick-Calenberg since the 1550s). In one of the last accountings of the votes allocated to German princes in the Diet, in 1792, Brunswick-Celle and Brunswick-Lüneburg (aka Hanover) are listed separately, as is Brunswick-Calenberg and Brunswick-Grubenhagen. By my reckoning that is seven individual votes, plus the collective vote in Westphalia, and one for Osnabrück—but what did this mean in practice? Did the King of England try to outvote other princes in imperial matters? I’ve asked some historians of the Holy Roman Empire, but never received a sufficient answer.

In Great Britain, King George I distributed titles to his family: his son Georg August was already Duke of Cambridge (from 1706), and from 1714 became Prince of Wales, Duke of Cornwall and Duke of Rothsay (and in Hanover was known as the ‘Electoral Prince’). Meanwhile, his daughter, Sophia Dorothea, succeeded her aunt as Queen of Prussia (and mother of Frederick the Great). The King’s younger brother Ernst August was, as we’ve seen, named Duke of York and Albany, and in 1721 his second grandson, William, was named Duke of Cumberland. The elder grandson, Frederick, had been left in Hanover to be raised as a German prince, far from the court of London. The King also named his half-sister (his father’s illegitimate daughter) Sophie Charlotte Countess of Leicester (in the Irish peerage), and Countess of Darlington (1721 and 1722), and his own mistress, Melusine von der Schulenberg, Duchess of Munster (1716, peerage of Ireland), then Duchess of Kendal (1719, peerage of Great Britain). There was never any mention of the Princess of Ahlden.

In the eighteenth century, the Hanoverians became increasingly English, though several younger sons were sent abroad to be educated at the University of Göttingen (founded in 1734 by George II). The Electorate was overrun by French armies in 1803, and in the post-Napoleonic settlements, was elevated to the rank of a kingdom in 1814. George III’s youngest son, Adolphus, Duke of Cambridge, was viceroy of the new Kingdom of Hanover, from 1816. From 1837, there emerges a separate story for Hanover again since Queen Victoria could not succeed to the German territories due to the Salic Law. Her uncle the Duke of Cumberland took over as King of Hanover, but his son, George V, lost the territory in 1866 after backing the wrong horse in the short war between Austria and Prussia for dominance in Germany. So we can finish off by looking at the development of the extensive properties in the old duchies of Brunswick and Lüneburg by its now royal house.

The gardens at Herrenhausen had already been expanded, with the addition of the George Garden and the George Palace (Georgenpalais) in the reign of King George III in 1817. These had been built by an illegitimate son of George II, Johann Ludwig, Count von Wallmoden, an imperial lieutenant-general and collector of art and antiquities. He built the Wallmoden Schloss in 1782 to house these treasures. Wallmoden’s mother had been Amalie von Wendt, created Countess of Yarmouth (1740), but he had taken his name from her husband (and legally his father), the Count of Wallmoden—from an ancient Brunswicker noble family from the area southwest of Wolfenbüttel. By the end of his life Johann Ludwig had been created count of the Empire, with his own vote in the Diet (for the immediate lordship of Gimborn), and was Commander-in-Chief of the Hanoverian army (1803). After he died in 1811, the castle and gardens were acquired by the King, and the gardens were developed in ‘English style’. Since 1921, they have been owned by the city of Hanover.

Nearby, King George V replaced the eighteenth-century Schloss Monbrilliant with a new neo-gothic structure, the Welfenschloss and adjacent gardens, the Welfengarten. There was a plan to move the official royal seat here from the Leinschloss, but exile from the Kingdom scuppered that plan and the palace was never fully completed. Today it forms the main buildings of the Leibniz University Hanover (since 1899); and the former grand stables are now the university library. The gardens remained property of the former royal family, however, until 1961, when they were sold to the city, keeping only a smaller residence on the grounds, the Fürstenhaus (built in the 1720s), which is still the family’s private residence.

Also still owned by today’s House of Hanover is Marienburg Castle, about 30 km south of Hanover. Built by George V in the 1850s as a present for his wife Marie as a grand neogothic fantasy, it sat mostly empty after the family moved to Austria in 1866—to Cumberland Castle, built in the 1880s on Lake Traunsee near Gmunden in Upper Austria.

After 1945, however, they moved back to Marienburg. In 1954, the heir moved to the nearby Calenberg estate and opened Marienburg as a museum. It was given to the current head of the family’s son, Prince August, in 2004, who used it primarily as the ‘formal’ seat of the family and management offices. But in 2018, August sold it to the state of Lower Saxony for a symbolic one euro, to a heritage foundation. His father blocked it in the courts, however, so it now belongs to a different charity, the Marienburg Castle Foundation, with August as chair. This year it began a major course of renovations that is expected to last nearly a decade.

The Duchy of Brunswick-Lüneburg had one last burst of life at the very end of the existence of the German principalities in the early twentieth century. After Prussia conquered the Kingdom of Hanover in 1866, its heirs were prohibited from exercising authority in any areas of the ancient duchy. Nearby, the duchy of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel continued, but became extinct in 1884—the heir would have been his distant cousin, the Prince of Hanover, also known by his British title the Duke of Cumberland, but the German government determined that unless he renounced his claims to the Kingdom of Hanover, he could not take over as Duke of Brunswick either. For thirty years, that territory was governed by regents appointed by the Kaiser. Then in 1912, Cumberland renounced his claims to enable his son Ernst August to marry Victoria Louise of Prussia, the daughter of the Kaiser (see here for an interesting ‘musing’ about this wedding). The wedding of May 1913 was the last great gathering of European royals before the First World War, with guests from George V of England to Nicholas II of Russia. As a sort of ‘wedding present’, the Kaiser restored the young couple to the Duchy of Brunswick, which they governed from November 1913 until the collapse of the German Empire in November 1918.

With the end of the war, the Duke of Brunswick was also deprived of his rank as a British prince and the title Duke of Cumberland. They lived on in exile in Austria then at Marienburg—Ernst August died in 1953, but his widow lived on until 1980, age nearly 90! The House of Brunswick-Lüneburg continues today as princes of Hanover in exile, but its names live on in incredibly diverse places all over the world. The state of Virginia has a Hanover County, a Brunswick County and a Lunenburg County (using the spelling prevalent in English in the eighteenth century). There is a New Brunswick Province in Canada, a city of Guelph in Ontario (with a university of the same name), and fourteen towns in the US called Brunswick, and seventeen towns called Hanover. Hanover island is in Papua-New Guinea, while Hanover Island is in the extreme south of Chile.

(images from Wikimedia Commons)

Dear Jonathan, Thanks for the latest blog which Jessica and I enjoyed. We both remember a very old film starring Steward Grainger as Konigsmarck and Joan Greenwood ( we think) as poor Sophia Dorothea. Wh

LikeLike

Wonderful thanks. Leonhard Horowski knows who murdered K. Best Philip

LikeLike