Once upon a time, in a far-off forest in Bohemia, a princess was attacked by a ferocious wolf. Her attendant bravely fought off the wild beast, and in gratitude, the princess ennobled her hero and granted him a coat-of-arms depicting the bold swipe of wolf’s claws on a blood-red field (some modern descriptors call these boar’s teeth). Centuries later, his purported descendants, the Kinskys, would rise to the ranks of princes themselves, and by the 19th century were amongst the richest noble houses in the entire Austro-Hungarian monarchy.

The Kinsky family emerged from legend into history in the early 13th century with the possession of an estate in northwest Bohemia around the village of Vchynice, from which they took their name. This is just outside the town of Lovosice on the great river Elbe as it flows north towards the mountains separating Bohemia from Saxony. Their lands were downriver from the estates that formed the core of another Czech house that survived the great purge of the native nobility by the Habsburgs in the 1620s, the Lobkowitz family, seen in a previous blog post. By the 14th century, the owners of Vchynice had taken it as their surname, and eventually dropped the first letter to be instead Chynsky (or ‘Chinitz’ in Latin sources), and added z (‘of’) Vchynic, or von Wchinitz in German. Today the family name in Czech is spelled Kinští, but they are commonly known in other European languages including English as Kinsky. They are not, it should be noted, related in any way to the famous family of actors descended from Klaus Kinski, whose original name was Nakszynski and who emigrated from northern Poland to Germany.

The family from Vchynice gained more lands and took on roles as royal officials in towns and forests in the Kingdom of Bohemia. Jan Vchynsky z Vchynice (d. 1590) was Burggraf (administrator of a royal castle) of Karlštejn, the famous castle built by Emperor Charles IV in the 1340s. His son Radislav (d. 1619) added greatly to his family’s landholdings (though Vchynice itself had been sold in the 1540s) and to its prestige. He was guardian of the orphaned sons of the noble Tetauer of Tetova family, and, noticing the similarity of their coat of arms, decided to claim kinship as well as their noble status (and, in good early modern practice, forged some documents as ‘evidence’), adding the name ‘Tetova’ to his own (c. 1596). Tetova, or Tettau in German, was an old fief in Lusatia, a province for centuries part of the Bohemian Crown, but lost to Saxony in the 1630s (today the town is just across the border, in the Province of Brandenburg). The von Tettau family continued on for centuries, active in Brandenburg and then Prussian court and military service—both families continue to use the same coat of arms, and many genealogies still say one family is an ‘offshoot’ of the other. And maybe they are.

The newly rebranded Radislav Kinsky z Vcynhic a Tetova (or Wchinitz und Tettau in German) was favoured by Emperor Rudolf II, King of Bohemia, and in 1611 was appointed Master of the Court of Bohemia, and given a seat in Bohemian Diet with the rank of ‘lord’ (pán) for himself and his family. His nephews, Radislav, Oldřich and Vilém were all actively involved in the great uprising of the Protestant Bohemian nobility against Habsburg rule in 1618—and the famous ‘defenestration of Prague’ of May 23rd. When this uprising was crushed after the Battle of White Mountain in 1620, Radislav fled, and Oldřich had his lands confiscated, like so many members of the old Czech nobility, soon replaced by loyal Austrian nobles. Somehow Vilém had sufficiently ‘acted obscurely’ during the revolt, and managed not only to hold on to the family estates, but was promoted in rank to ‘Count Kinsky’ in 1628. This was mostly due to his association with rising Imperial warlord, Albrecht von Wallenstein (or in Czech, z Valdštejna)—his wife’s brother’s wife was Wallenstein’s wife’s sister, if you can follow that (or his brother-in-law was also brother-in-law of Wallenstein). At some point in the early 1630s, Count Kinsky was living in exile in Dresden in Saxony, and tried to get Wallenstein to switch allegiances and join the Protestant side of the Thirty Years War—this did not happen, but they remained close, and were both assassinated by agents of the Emperor who feared the rising independent strength of his own general, at Cheb (Eger) in February 1634. One of his estates that was confiscated was the mighty castle of Teplice (Teplitz) in the mountains of the northwest—it had only been acquired by the family in 1585, but from here on was one of the principal residence of the princely Clary-Aldringen family (so will properly be looked at for that family).

The youngest of all those brothers, Jan Oktavián, in the years before the uprising, had been chamberlain of Emperor Matthias (successor of Rudolf II), and obtained the castle and estate of Chlumec nad Cidlinou, in 1611. This castle on the river Cidlina is northeast of Prague, built in the 15th century and expanded by the Pernštejn family in the 16th. It was the Kinsky seat until a new castle was built in 1721-23 just outside the town, Karlova Koruna (see below). The older castle fell into disrepair and was finally town down in the 1960s.

Jan Oktavián was pardoned after the events of 1618-20, and consolidated the landholdings of all the branches over the next several decades, notably the castle of Česká Kamenice in the farthest northern corner of Bohemia. Built in the 1530s by the Vartemberks, it had been purchased by Radislav Kinsky, and stayed in the family until 1945. Since then it has been used as housing for the state forestry administration.

All the current Kinskys descend from Count Jan Oktavián. He took on his father’s office of Master of the Court from 1646—an office passed to his two sons then two grandsons before it was finally confirmed as hereditary by Maria Theresa in 1743. The Kinsky Masters of the Court (Hofmeister in German, Hofmistr in Czech) would thus perform a key role when any Habsburg visited Bohemia, but most importantly at their coronations in Prague. Jan Oktavián was confirmed in his rank of count in 1676 and died three years later.

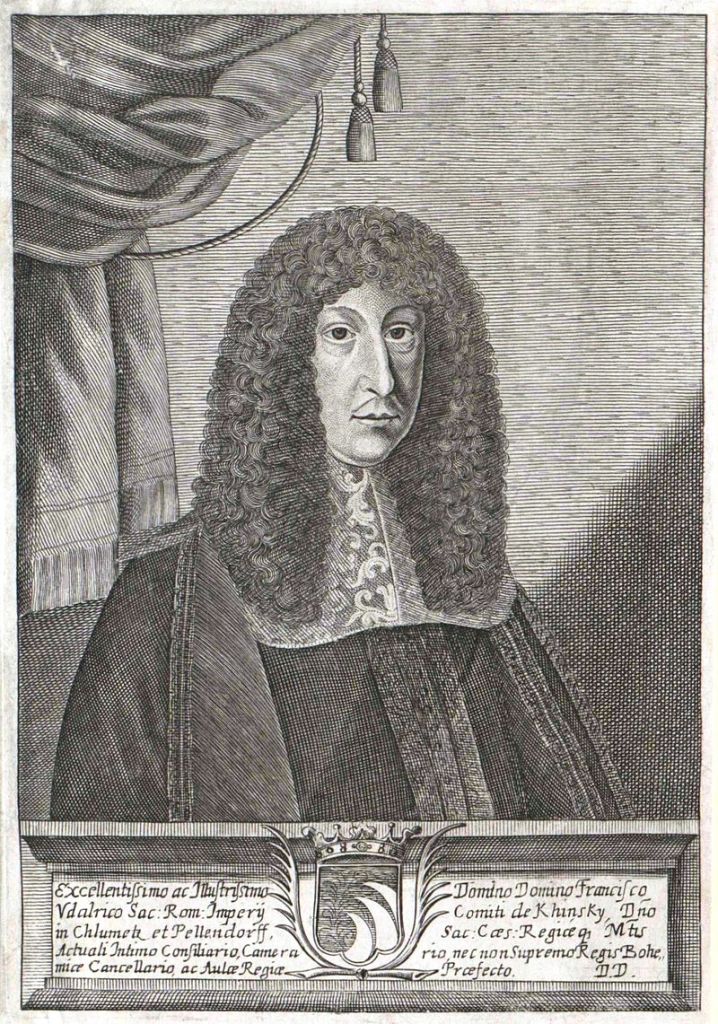

His son Count František Oldřich (Franz Ulrich) (d. 1699) was thus Master of the Court and also High Chancellor of Bohemia, 1683, and a member of the Emperor’s privy council from 1689. In the 1690s he was one of the leading members of the Imperial court and led important negotiations with the Ottomans. Two other Kinskys held the highest judiciary office in the Kingdom of Bohemia: František Oldřich’s brother Václav Norbert (d. 1719), in 1705-1711, and the latter’s son, František Ferdinand (d. 1741), 1723-36. The latter was a diplomat and organised the election in Frankfurt of the Archduke Charles of Austria as Holy Roman Emperor Charles VI in 1712.

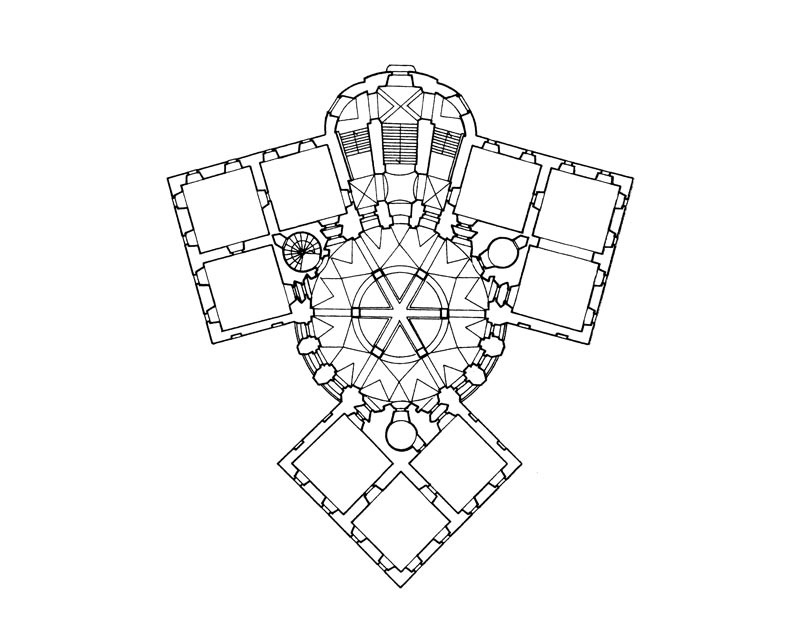

Count František Ferdinand built a new family residence at Chlumec, Karlova Koruna Castle in the early 1720s: named ‘Charles’ Crown’, in honour of the coronation of Emperor as King of Bohemia. This castle, a baroque pleasure palace with a unique floorplan, on a small hill overlooking a park, is still in amazing shape, and was restored to the Kinsky family in 1990 following the period of Communist rule. The nearby hexagonal Chapel of the Annunciation (later of St John the Baptist) became the family sepulchre for many years.

Count František Ferdinand also acquired the Castle of Eckartsau in Lower Austria, 1720, an ancient medieval castle which he remodelled as a in Baroque style. Located on the Danube between Vienna and Pressburg (today’s Bratislava), it made a convenient stopping point for the Imperial family, so Emperor Francis I purchased it in 1760—it was thus only a Kinsky property for 40 years—it later became famous for hosting the last court of Austria-Hungary in 1917-18, and was the place of abdication for the last emperor, Charles I, in November 1918.

František Ferdinand had three sons, all high-ranking military commanders in the second half of the 18th century. His second son Joseph in particular was Commander of the Army of Hungary in 1787, then of the entire Habsburg army in 1788. His younger brother Franz Joseph became Director of the Theresian Military Academy in Vienna, founder of an army cadet school in Prague, and all-round pedagogical wonder of his century. The eldest, Leopold Ferdinand married a Liechtenstein princess and founded the senior line of the Kinskys, the Chlumsky Branch. There are still several Kinsky counts around descended from this line, but they are not princes.

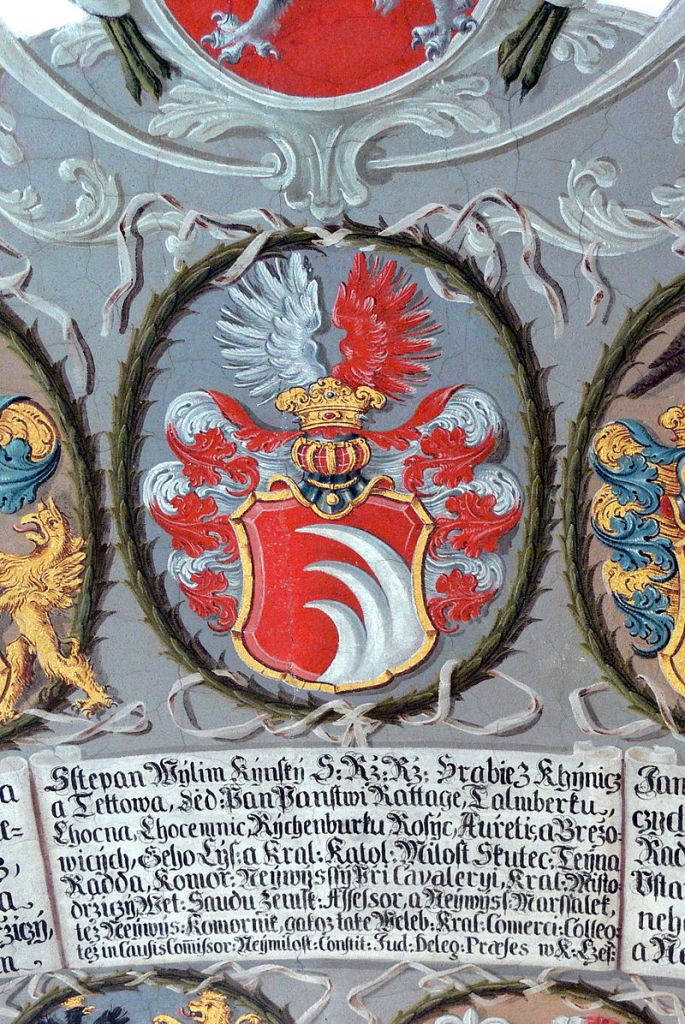

It was Václav Norbert’s second son, Štepán Vilém (Stephan Wilhelm) (1679-1749) who promoted his branch of the family into the highest ranks of the Habsburg nobility. He served Emperor Charles VI as a diplomat—St Petersburg and Versailles—and was Grand Marshal of Bohemia, 1733, and Grand Master of the Court. In 1746, the Emperor’s grateful daughter and successor, Maria Theresa, as Queen of Bohemia, created him Prince Kinsky von Wchinitz und Tettau; a year later, he was also created Prince of the Empire by Maria Theresa’s husband, Francis Stephen of Lorraine, recently elected as Emperor Francis I. Unlike most princes of the Empire, the Kinskys did not hold an immediate fief, so the title was attached to the person, and was only held by the senior male (so other children were count/countess). It did not bring the family a vote or a seat in the Imperial Diet.

When the Kinsky estates were divided, the first Prince Kinsky received as his share the castles at Česká Kamenice (see above) and Choceň. Choceň (Chotzen) was located in the Pardubice region. It was a market town with a castle built in the 1560s and rebuilt in the 18th century, by which point it was in Kinsky hands. The family completely rebuilt it after a fire in 1829, and used it as a favoured summer residence in the next century. Since 1945 it has housed an art school and a history and archaeology museum.

Franz Joseph, 2nd Prince Kinsky, succeeded his father in 1749, but he died in 1752 at age 26 with no male heir, so the succession passed to a first cousin. The first Prince’s younger brother, Philipp Joseph, had also been a diplomat, notably the Imperial envoy to London, 1728 to 1736. He then served, like so many of his forebears, as High Chancellor of Bohemia, 1738, and one of the close advisors to Empress Maria Theresa in the first years of her reign. But he too died relatively young, in 1749, meaning that the succession went instead to his son, Franz de Paula Ulrich. A younger son, Johann Joseph, became an entrepreneur on his estates—glass and textiles—and founded another line of Kinsky counts.

The 3rd Prince Kinsky (1726-1792) had a long military career, rising to the rank of General of Artillery in 1767, Director-General of the Austrian Artillery, 1772, then Field Marshal, 1778. He purchased grand residences in two of the Habsburg capitals: Prague and Vienna. The Kinsky Palace in Prague, located right on the Old Town Square (Staroměstské náměstí) in the heart of the historic city, had initially been built in the 1750s by the Golz family, then purchased by the Kinskys in 1768. A distinctive pink and white rococo palace, it also had spaces for shops on the ground floor that opened up onto the square: at the end of the 19th century, Franz Kafka’s father had a haberdasher’s shop here, and young Franz himself went to secondary school located on a higher floor. In the 1920s-30s it served as the Polish Legation to Czechoslovakia, and since 1949 has been part of the National Gallery.

On the other side of the Vltava River that flows through Prague, the Kinskys built a Summer House, in about 1830, and a Romantic garden with rare trees and waterfalls. Since 1901 the Summer House has housed a museum of ethnography.

Meanwhile, in Vienna, Prince Kinsky purchased in 1784 a palace built by the Daun family in 1713 on the northwest edge of the old city close to the University, facing onto a large square called the Freyung. In the 20th century, the Palais Kinsky passed out of the family to a daughter who married an Argentine, so it became the Argentine Embassy in the 1960s. Sold by the family in 1987, it was restored and re-opened in the 1990s as an auction house and a place for fancy receptions—its lower levels house shops and restaurants.

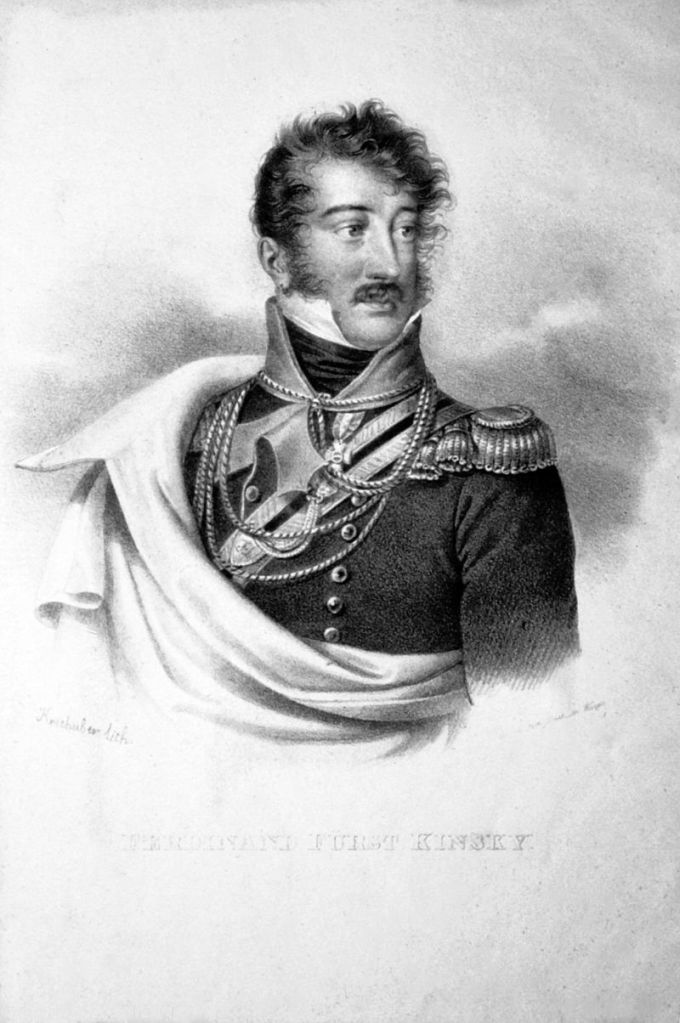

The princely line of the Kinskys in the later 18th and early 19th centuries was quite limited in terms of the number of sons, meaning that the family’s wealth did not need to be divided amongst heirs. Like many of the great aristocrats in Vienna in this period they were great patrons of music: Joseph, 4th Prince Kinsky (d. 1798) was a patron of the Czech musician Pavel Wranitzky—who is not very famous, but has wonderfully bold music in the heroic vein of late Haydn—while the 5th Prince, Ferdinand (d. 1812), was an important patron of Beethoven from 1809—one of the aristocratic trio that included Archduke Rudolf and Prince Josef František von Lobkowitz—the three paid him a pension to enable him to stay permanently in Vienna and not seek employment elsewhere. But he soon died; his widow continued the pension, and was thanked by means of a song, An die Hoffnung (‘to hope’).

Another junior branch was created by Ferdinand’s younger brother, Count Franz de Paula. The most prominent member of this line was his daughter, Franziska, who became Princess-Consort of Liechtenstein as wife of Prince Aloys II (r 1836-58), and then regent of the principality for her son, 1858-60.

Rudolf, the 6th Prince (d. 1836), was part of the Czech national revival movement that took hold of much of the Bohemian elite society in the 1820s—in particular he supported the creation of a National Museum in Prague. Though mostly still based at Choceň Castle, in 1828, he also added to his family’s estates through the purchase of Heřmanův Městec (Hermannstädtel in German), a town east of Prague towards the hills of Moravia. He improved the town, built and orphanage and hospital, and extended the old castle and developed its English style gardens. Since the 1950s, this castle has housed a retirement home.

The 4th, 5th and 6th princes all died relatively young, in their 30s-40s; in contrast, the 7th Prince Kinsky, Ferdinand Bonaventura (d. 1904), lived until he was 70. He sat as a hereditary member of the Austrian House of Lords, but was not very political. Instead, he developed his estates in Bohemia, notably its industries, sugar and beer. He had three sons and a daughter, Elisabeth, whose daughter once again connected this family to the House of Liechtenstein: Georgina von Wilczek was Princess-Consort of Liechtenstein from 1938 to 1989.

The eldest son, Karl, 8th Prince Kinsky von Wchinitz und Tettau (d. 1919), only outlived his father by 15 years. As heir, he had long made his name as one of the premier equestrians in Europe. In particular, he was passionate about horseracing in England. In 1883, he himself rode his prize-winning horse (Zoedone) to victory at the Grand National.

Horses had in fact been an important aspect of the Kinsky dynastic identity for centuries. A Kinsky was put in charge of the Emperor Charles VI’s newly commissioned stud farm in eastern Bohemia in 1723, to breed horses specifically for elite cavalry units. These were the famous ‘Kinsky Horses’, with a distinctive gold colour and renowned stamina. Count Oktavián, from one of the junior branches, was one of Europe’s most successful breeders in the mid-nineteenth century, and introduced English style racing to the Austro-Hungarian monarchy in 1874—an event still held today (the Grand Pardubice Steeplechase).

The 8th Prince managed to stay in England for many years by serving in a diplomatic post, as Austrian attaché to Great Britain. He became very close, maybe too close, to Lady Randolph Churchill (the American-born Jennie Jerome). When he was recalled to Austria-Hungary due to the outbreak of World War One, he accepted a military command but arranged it so he would fight only on the Eastern Front against Russia, and never against Britain. In December 1918, noble status was abolished shortly after the declaration of the independent republic of Czechoslovakia; then in April 1919, titles of nobility were abolished for Austria too. In December that same year the 8th Prince died, and was succeeded by his brother, Rudolf, the 9th Prince, who died in 1930 leaving five daughters.

The princely title thus went to his nephew Ulrich (Oldřich). This prince’s father, Count Ferdinand Vincenz (d. 1916), had served in the last decade of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy as Master of the Horse for Emperor Franz Josef. He lived at Moravský Krumlov, inherited from a maternal uncle, and Horažd’ovice. The former, in southern Moravia, is a huge castle from the 13th century, built by the Lipá noble family and held until 1620—it was then held by the Liechtensteins until passed to Prince Kinsky in 1908 (so it mostly belongs in their story). Today the castle belongs to the town and is slowly being restored back to its former glory. Horažd’ovice Castle is a more modest building, in the far west of Bohemia, bought by Prince Kinsky in 1843. A 13th-century Gothic castle was replaced in the 15th century by the Švihovský family, who, as we’ve seen with so many others, had their lands confiscated in 1620. The Kinskys developed local industries here, notably pearl oyster farming. It too belongs to its town and houses a variety of civic spaces: a city museum, gallery, information centre, youth centre, library and a restaurant too!

Prince Ulrich was born at Choceň. Like so many of his ancestors, he did not have a long life (1893-1938), but in his final years he impacted the future of the family through his strong support of the Sudenten German Party which advocated annexation of much of western and northern Bohemia by Nazi Germany, a fateful decision that heavily impacted the future of his dynasty.

His son Franz Ulrich, 11th Prince Kinsky (1936-2009), emigrated as a child with his mother to Argentina, where he spent most of his life. At the end of the Second World War, his family’s lands were confiscated due to his father’s political stance, first by the restored republic, then by the Communist regime. They were not restored following the ‘Velvet Revolution’ of the 1990s, as many estates were to old Czech noble families. In 2003, many (over 150) lawsuits were filed versus the Czech state, pressing claims totalling over 13 billion Euros. The Prince argued that he was only two in 1940, and that his mother’s family, Bussche-Haddenhausen, were strongly anti-Nazi.

His son, Karel Maximilian (‘Charlie’ or ‘Carlos’), 12th Prince Kinsky (b. 1967, in Buenos Aires), succeeded in 2009 and renewed the application to the Czech government for restitution of lands in 2012, and the European courts upheld his claim that his father (the child in the 1940s) had not been given a fair trial. It remains pending. He is married and has an heir, Wenzel (Václav) Ferdinand (b. 2002).

Yet another Liechtenstein connection was made by the 11th Prince’s first cousin, Countess Marie Kinská, who in 1967 married the Hereditary Prince Hans Adam II, who has reigned since 1989. The Princess of Liechtenstein died in 2021.

Today there remain three main lines of the House of Kinsky: the princely branch (nominally based) at Choceň and two branches of counts, at Kostelec and Chlumec. Unlike the princely line, these branches were more firmly identified with Czech nationalism in the 1930s, and although they also had their castles and estates appropriated by the Communist regime after 1945, they were recovered in the 1990s.

The Kostelec branch was founded by a second son of the 5th Prince Kinsky at the end of the 18th century. The Castle Kostelec on the Orlice river is in northeast Bohemia, a ‘fortified church’ built in the early 14th century then held as a castle by various families until purchased by Josef Kinsky in 1796. A newer castle was built here by this branch of the Kinskys in about 1830, in neoclassical style. The two buildings were restored to the Kinskys in the 1990s, and house a gallery and town history museum.

The Chlumec (or Chlumsky) branch, as seen above, is actually the senior line, formed by the elder brother of the 1st Prince at the start of the 18th century. One of these, Count Zdenko Radslav Kinsky (d. 1975), was the instigator of the 1938 Declaration of members of the old Czech families proclaiming the inviolability of the territory of the Czech state and protesting any idea of its dismemberment or a takeover by Nazi Germany. His properties were confiscated when this failed and a Nazi protectorate was established in Bohemia. It was returned in 1945, then confiscated again by the Communists in 1948. He emigrated to France and died in Rome.

Count Zdenko’s son, Count Václav Norbert (d. 2008), married an Italian heiress and added her surname, dal Borgo, to his own. Late in life he became active in the Order of Malta—no longer crusading knights, but a global Catholic charity—and served as ambassador from the Order (which is based in Rome) to the Republic of Malta, then as Grand Prior of the Order in the Czech Republic, 2002-2004. The Kinsky-Dal Borgo branch reclaimed Chlumec, Karlova Koruna and other castles in the 1990s, and have been avidly restoring them.

Another member of this cadet branch, Count Christian (d. 2011), married the heiress of a mighty fortress in Austria, Heidenresichstein, in the far north of the country near the border with Bohemia. A moated castle with several towers, it was built in the later twelfth century, and was held by two families—amongst others—for about three centuries each: von Puchheim and Palffy. The latter died out in 1942, and ultimately the inheritance went to the Kinskys, who still own it today.

(images Wikimedia Commons)