If a beautiful fortress in French-speaking lands gave its name to a dynasty or two of dukes and princes (‘Beaufort’), then attractive castles in German-speaking lands can too. There are certainly a number of castles in Germany and Austria named schön burg, or the similar yet different schön berg, referring to a mountain, not a castle. Given how much noble families liked to build their castles on mountaintops, it is therefore not surprising that there are several von Schönburg or von Schönberg noble families. This blog piece will look at three of them, two from Saxony in east-central Germany, and one from the Rhineland in the west. All three shifted the scene of their activities at different points in their history: one (Schönburg) became princes and migrated to Austria and Bohemia; another (Schönberg) became military leaders in France (as ‘Schomberg’) and married into a dukedom (Hallwin); while a third (spelled either way) moved first to France (and also took on the latter spelling), then to England where they too became dukes. Perhaps even more extraordinarily, this last family also received a second dukedom, and it was the second ducal title ever in the peerage of Ireland—the short-lived dukedom of Leinster (in its first creation).

This post will be hard to categorise therefore: Germany? Austria? France? England? Ireland? It’s another good example of how truly mobile many of these elite families were in the eras before the divisive forces of nationalism took hold in the nineteenth century. Neither the French nor English Schomburg dukedoms lasted very long, so the only family still extant today are the Schönburg princes in Austria.

All three families traced their origins to the 12th and 13th centuries; but of the three, only the family that ended up as princes were very significant before the late 16th century. The first who obtained top rank however was the Saxon family who ended up as marshals of France and dukes of Hallwin, so we will start there. In the early 13th century, a Saxon knight called Hugo was named Castellan of Rudelsburg, one of the defensive castles of the bishops of Naumburg, whose diocese was in the borderlands between Saxony and Thuringia. It is suggested in some sources that Hugo’s family were a branch of a family long in service to the bishops of Naumburg who took their name from a castle on the other side of the city, high above the River Saale, Schönburg. By the 14th century both of these two families, one called Schönburg and the other Schönberg, had focussed their landholdings further south and east into Saxony. Schönburg Castle itself, long used as the summer residence of the Naumburg bishops was seized by the Electors of Saxony when their diocese was secularised in the Reformation, and it was used as an administrative building for a while, then slowly degenerated. In 1815 it became part of the Prussian province of Saxony (not the Kingdom of Saxony, just next door), and it has been maintained as a romantic ruin ever since.

We’ll return to the Schönburg family, who became much more prominent by the and of the 13th century (and ultimately princes), later. For now, we’ll look at the Schönberg family, who remained fairly minor nobles for quite a while. They moved east into the Margraviate of Meissen, and built a castle, Rothschönberg (‘Red Schönberg’, c. 1300), west of Dresden, the city that eventually became capital of the Electorate (and later kingdom) of Saxony. Other castles were acquired in this region, like Sachsenburg; and further south towards the mountainous border with the Kingdom of Bohemia, notably Purschenstein (1380) which had been built two centuries earlier to guard the important trade routes coming out of Czech lands. Further east in the still quite heavily Slav-populated Lusatia they acquired the lordship of Pulsnitz (or Połčnica in the original Sorbian).

Over the next several centuries these Schönberg lords provided the dukes and electors of Saxony with numerous chamberlains, soldiers and administrators—all the way up to the end of the independent Kingdom of Saxony in 1918. One post held repeatedly by this family from the 16th to the 18th century was ‘Grand Master of Forges, Mines and Forests’ which surely brought them a healthy income as well as prestige. The dynasty also supplied the Church with a number of senior clergy: two bishops of Meissen (1451-76), then two bishops of Naumburg (1480-1517). In the next generation, Nikolaus von Schönberg became Archbishop of Capua in Italy (1520), and a Cardinal (1535)—and notably, a strong supporter of the new ideas of Nicolas Copernicus about the movement of the planets. His brother Anton went even further into the realm of reforms, and became an early leader of the Lutheran reformation in Saxony.

When the Wars of Religion broke out in this region, Wolf von Schönberg, Lord of Sachsenburg, commanded some of the Saxon armies in the fight against the Catholic armies of the Emperor. He was named Marshal of the Court of Dresden. His eldest son Hans was, like several of his predecessors, Superintendent of the Mines. But his second son, Caspar, travelled to France in about 1560 and lent his sword to the Protestant cause there. For whatever reason, he then converted to Catholicism in 1568, was naturalised as French and named a field marshal in the armies of the King, who sent him on missions to try to reconcile the Catholic cause with the German Protestant princes. Gaspard de Schomberg (as he was now known) also became a favourite of the King’s younger brother, Henry, Duke of Anjou, and accompanied him to Poland in 1574 when he was elected king there. Gaspard had also brought his younger brother, Georg, to the French court, and helped him obtain a position of page in the household of the Queen Mother, Catherine de Medici. Georges also went with Anjou to Poland—and swiftly back when Henry discovered he had become king of France (Henry III) in 1575. Georges de Schomberg then took part in the famous ‘Duel of the Mignons’ in April 1578, in which the King’s beautiful young men did battle, Georges taking the side of the King’s rival, Henri, Duke of Guise. After a good start, Shomberg was stabbed in the heart and died. It was a shocking event and one of those that convinced the people of Paris that the court had become a den of depravity.

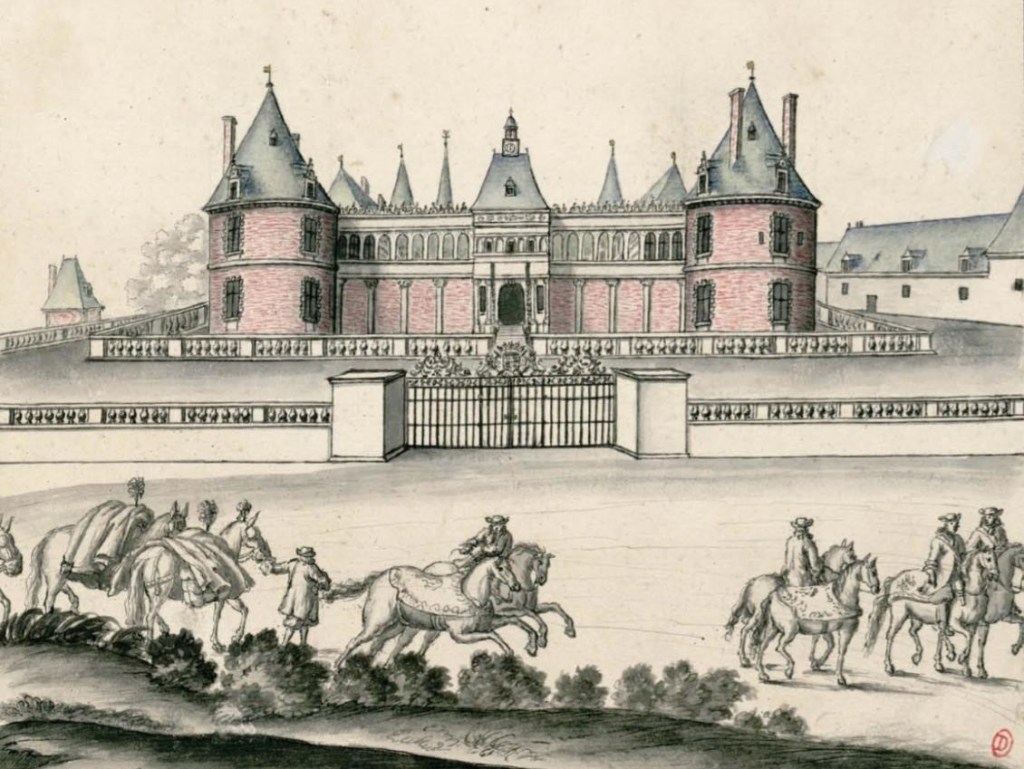

Meanwhile, Gaspard’s fortunes continued to rise. In 1578 Henry III granted him the County of Nanteuil and its beautiful Renaissance château north of Paris in the province of Valois. It had been the chief residence of the Duke of Guise for two decades, so this was a real sign of the King’s favour (and perhaps remorse over young Georges’ death). The Château de Nanteuil was held by this family until the 1650s, then passed to the Estrées dukes, and in the 18th century to the princes of Condé, Bourbon cousins of the kings of France—sadly it was destroyed during the Revolution.

The new Count of Nanteuil was evidently not liked by the Holy League (that is, the supporters of the Duke of Guise); so after King Henry III’s death in 1589, Schomberg fled to Saxony. But he soon returned to support the new reign of Henry IV, again using his Protestant connections, and in 1594 was appointed the King’s Superintendent of Finance, a post he held for three years, a crucial time for the first Bourbon king rebuilding the French government after the devastation of the Wars of Religion. Gaspard de Schomberg died in 1599. He had married a French noblewoman and left behind a very French son, Henri de Schomberg.

Just before his father died, Henri also married a French noblewoman, Françoise d’Espinay. She was an important heiress, bringing to the marriage the massive medieval fortress of Durtal, on a rock overlooking the River Loir in Anjou. This castle later passed to the La Rochefoucauld dukes (via the heirs of his daughter Jeanne), and in the 19th century became a hospital, and today a private residence once more. Henri, Count of Nanteuil and Durtal, was also Superintendent of Finance, for Louis XIII (1619-22), then was named Grand Master of the Artillery, 1622, and Marshal of France in 1625. Marshal de Schomberg led royal forces against French Protestants in the years that followed, notably at the Siege of La Rochelle, notably defeating a number of English troops sent by King Charles I under the command of the Duke of Buckingham. In 1630 he led an army across the Alps and captured the important Piedmontese fortress of Pinerolo—long the key to the French strategic position in northern Italy. Back in southern France, he arrested the rebellious duke of Montmorency in 1632, and replaced him as governor of Languedoc. But he died only a month later, so the post was given to his son.

This son, Charles, was the first we’ve encountered so far to enter the very highest aristocracy, as Duke of Hallwin. But he wasn’t created duke on his own merits, and in fact he had to share the title with someone else! Hallwin was a lordship in French Flanders which gave its name to a long line of lords—though how it was spelled in this Dutch/French language border zone was incredibly diverse: Halewijn, Hallewyn, Halluin, Alluyn… One of these lords, Charles, was created Duke of Hallwin and Peer of France in 1587. He and his family will have a separate blog post. The first duke was succeeded by his grandson, Charles II, who died with no heirs in 1598; his sister Anne was allowed to retain the title duchess (unusually for France where dukedoms tended to be males-only fiefs). Duchess Anne first married in 1611, Henri de Nogaret, the son of the Duke of Epernon (one of the great royal favourites of the previous two reigns). He took the title Duke of Hallwin in the name of his wife, but was also sometimes called Duke of Foix-Candale having inherited that estate from his mother. They divorced, and in 1620, Duchess Anne re-married, this time to Charles de Schomberg-Nanteuil. The title was recreated on a different Hallwin fief, Maignelais (still in Flanders). Strangely (or at least as described later by the Duke of Saint Simon who was obsessed with such things), her previous husband was allowed to continue to use the title of Hallwin, and especially its peerage which granted him a seat in the Parlement of Paris. At royal ceremonies, the ex-husband Hallwin was given precedence over current husband Hallwin since dukedoms were ordered by year of creation. But at Parlement, there could only be one person sitting as Duke-Peer of Hallwin, so apparently they admitted whichever arrived first and turned the other away. There were no children from either marriage, so when Henri de Nogaret died in 1639, then Anne d’Hallwin in 1641, the situation was resolved.

Charles de Schomberg, Duke of Hallwin, took over from his father as Governor of Languedoc in 1632, was also created Marshal of France in 1637, after successfully blocking a Spanish invasion in the eastern Pyrenees in the Thirty Years War. He later became Governor of the Three Bishoprics (Metz, Toul and Verdun), in 1645, and at court held the important post of Colonel-General of the Swiss Guard. In 1646 he took a new wife, Marie de Hautefort, the late king Louis XIII’s favourite and confidante, but now exiled for having taken part in an attempted coup against his widow, Anne of Austria. Ever part of the ultra-pious faction as court, Marie drew her husband into more pious circles and later in life they became strong supporters of conversion societies that aimed their efforts towards Calvinists and Jews. The Marshal-Duke died in 1656 without any children, so this part of this story comes to an end.

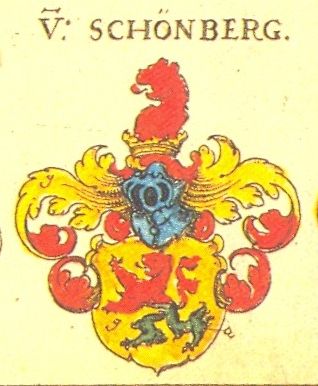

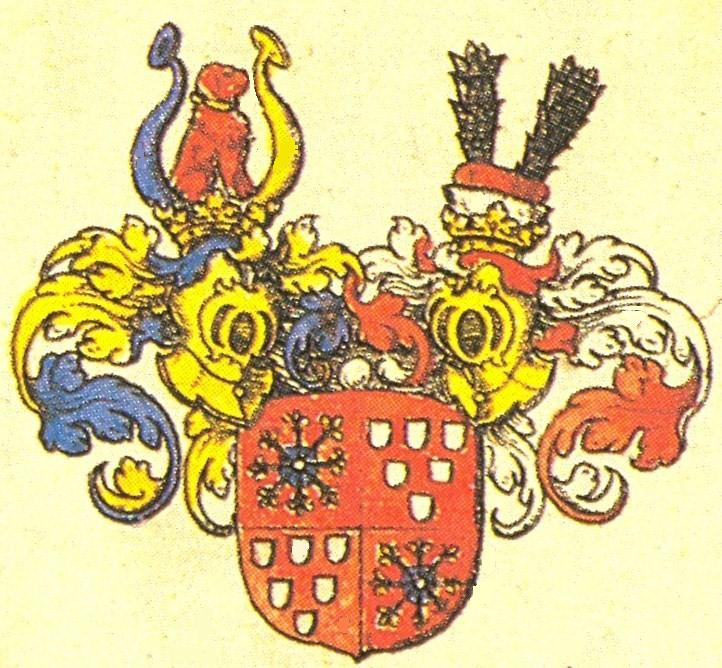

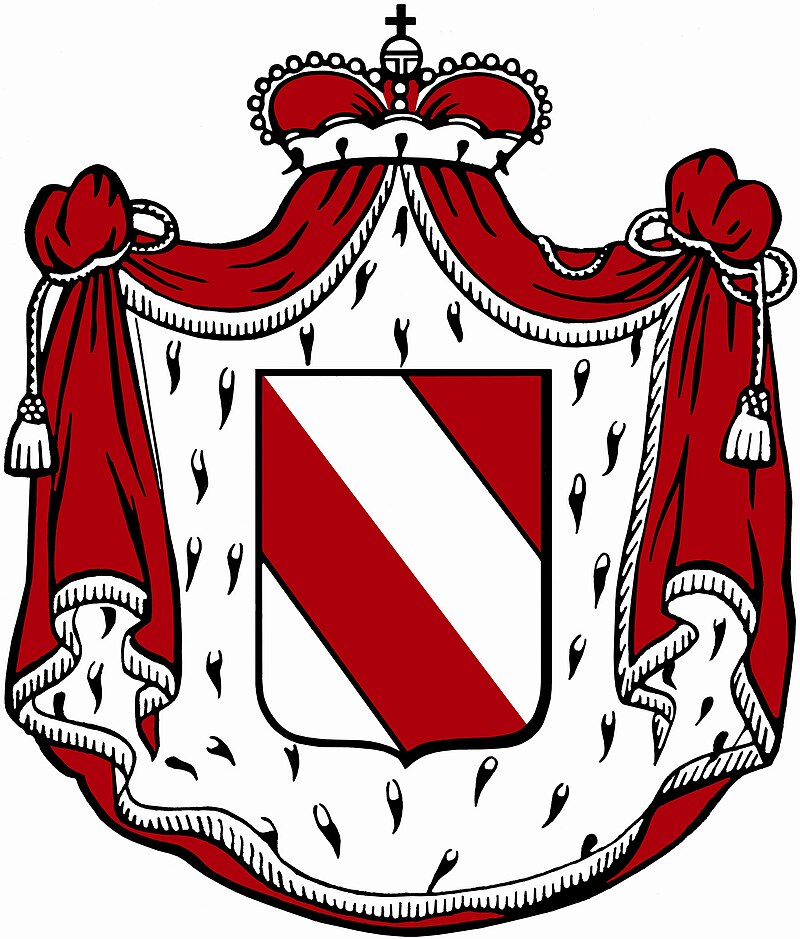

But not exactly: Marshal Schomberg had supported the career of a younger man in the French army, also called Schomberg. Despite adhering to different religious confessions, and their families having quite different coats of arms (the usual indicator of one noble lineage’s kinship with another), the French seemed to accept that these two German soldiers were from the same house. In fact, the Saxon Schönbergs used a red and green rampant lion on yellow, while these Rhenish Schönburg/Schönbergs using a more complex shield made up of an ‘escarbuncle’ of eight golden rays on silver, quartered with an array of six silver shields on red. The third Schönburg family surveyed here, those who became princes, used a much simpler design of red and white diagonal stripes.

The Rhenish Schönbergs took their name from another castle called Schönburg, this one called ‘in Oberwesel’, the Wesel being a village on the left bank of the Rhine, just one bend upriver from the famous Lorelei rock. Built in the 12th century it was a fief of the Elector-Archbishop of Trier, who ruled much this side of the river. An old family of ministerialis (a type of service nobility in early medieval Germany) was given this fief and took it as their name (in the 1150s). Much later, the castle was destroyed by a devastating French invasion of the region in 1689, and as the resident branch of the family died out in 1719, the fief returned fully to Trier but was seldom used and began to crumble. It would be restored in the 1890s by a wealthy socialite New York family, the Rhinelanders (with a very fitting surname); then after the Second World War it was acquired by the town of Oberwesel, and today it is run as a hotel.

Over the centuries, the family divided into several lines and went into service of either the imperial archbishops (Cologne, Trier, Mainz), or one of the powerful territorial lords, like the Elector Palatine or the Count of Nassau. One branch remained Catholic and was most famously represented by Baron Otto Friedrich von Schönburg, a General Field Marshal for the Catholic League in the Thirty Years War (killed at the Battle of Breitenfeld in 1631). His brother and heir, Johann Karl, was an Imperial councillor and was created Count von Schönburg in the 1630s. He was also Count of Montigny and other places in Luxembourg due to an ancestor’s marriage in the previous century.

Another branch began at some point to spell the name Schönberg; and were elevated to the rank of count by the early 17th century. Count Meinhard was a soldier in the mercenary Protestant armies of Count Palatine John Casimir in the French Wars of Religion. His son Hans Meinhard continued the link with the Wittelsbach rulers of the Palatinate, first as a diplomat for Elector Frederick IV, being sent to Emperor Rudolf II in Prague and to the Dutch States General to try to hold the peace in a succession crisis of 1609. Then when Frederick IV died, he moved into service of his son Frederick V, who appointed him Master of his Household in 1611. He then made his family’s first connections with the Stuarts in England by travelling to London to arrange the marriage of Princess Elisabeth, daughter of James I, with his master Elector Frederick. While at the English court he met Lady Anne Sutton, daughter of the Baron of Dudley (she’s sometimes called Anne Dudley). They married in 1615, and she soon gave birth to a son, but sadly died immediately after. Hans Meinhard himself died a year later in 1616.

The orphaned child Friedrich was raised by his guardians in Heidelberg, then sent to the Sedan Academy, a proper boarding school for young Calvinist noblemen, then to Leiden University in Holland. In the Thirty Years War, he led Dutch then Swedish troops against the forces of the Catholic League, then moved into French service after 1635 when that Catholic kingdom curiously entered the war on the Protestant side. In 1639, he married his cousin Johanna Elisabetha von Schönberg, which consolidated the succession as she was co-heiress of many of their family properties. They had three sons: Friedrich, Meinhard and Karl. In the 1640s, Count Friedrich once again fought in Dutch armies, then in the 1650s returned to France, where he was promoted to Field Marshal (1652) then Lieutenant-General (1655). As noted above, some sources suggest that his initial introduction to the French army, and his rapid promotion were due to an assumed (or projected?) kinship with Marshal de Schomberg. He too started spelling his name the French way. Their difference in religion didn’t seem to matter.

In the 1660s, the half-English, half-German French commander Frédéric de Schomberg took an even more unusual turn: he led English troops sent by King Charles II to Portugal to help that country regain its independence from Habsburg Spain. He had the support of Louis XIV in this, but since France had *only just* signed a peace treaty with Spain, he officially had to work for the British king. In 1663, he was rewarded by the Portuguese king with the title Count of Mértola and a significant pension. Sources conflict whether this was a ‘for life’ only title, or whether it passed to his descendants (see below). It is also unclear whether the title also included the ancient Moorish castle (mostly a ruin by the 17th century) and estates (very lucrative for their mines), in the far southeastern region of Portugal near the border with Spain. Schomberg even took part in the coup against King Alfonso VI in 1668 led by the Queen and the King’s brother Dom Pedro.

Schomberg was back in France by 1669 when he married for a second time, Suzanne d’Aumale, Dame d’Haucourt, one of the cultured and intellectual women of Parisian salon society known as the précieuses (not flatteringly—people thought their ‘precious’ mannerisms were affected and snobbish). He then set off to war once more, as commander of a French army invading Catalonia, 1674 (this time overtly fighting against Spain), and was created a Marshal of France in 1675. The new Marshal Schomberg then commanded on the northern front against the young Dutch Stadtholder, William III, Prince of Orange, in 1676. He faced him again on the battlefield in the next war in 1684—but the very next year, everything changed.

In 1685, Louis XIV revoked the Edict of Nantes (the religious peace brokered so painstakingly by his grandfather Henry IV), and Marshal Schomberg had to make a decision: renounce Protestantism and become a Catholic, or move abroad. Unlike his more ‘amenable’ cousins earlier in the century, this Schomberg remained true to his faith. He first moved to Brandenburg, where many French Huguenots were given asylum, and took up command as a general in the armies of ‘the Great Elector’, Frederick William of Brandenburg. In 1688 he was asked to be second in command in the armies led by his former opponent, William of Orange, as they embarked on the ‘Glorious Revolution’ to save Great Britain from the Catholic absolutist tyranny of King James II. When William then became co-king (with his wife Mary) in 1689, Schomberg was named Master-General of the Ordnance, awarded the Order of the Garter, and in May was created Duke of Schomberg, with subsidiary titles, Marquess of Harwich and Earl of Brentford. He was also given £100,000 to compensate for the lands and revenues he had lost in France (such as the estate of Courbet outside of Paris). This German-French-British duke then died in Ireland, at the moment of victory over the forces of James II at the Battle of the Boyne, 1 July 1690. He was buried in Saint Patrick’s Cathedral, Dublin.

Of the 1st Duke of Schomberg’s sons, the eldest, Count Friedrich, served with his father in France and in Portugal, then returned to Germany. In theory he inherited the Portuguese title Count of Mértola, then after his death in 1700, passed it to his daughter, the wife of the Count of Sayn-Wittgenstein-Berleburg. The youngest son, Charles, had been named in the creation of the dukedom as heir to the dukedom (perhaps as the second son was already being considered for a dukedom of his own?), so became 2nd Duke of Schomberg in 1690. Charles had moved in military service with his father, as a lieutenant-general in the army of Brandenburg, then in the invasion of England of 1688. During the Nine Years War (1688-97), William III sent him to command French Huguenot troops (in the pay of England—the Schomberg Regiment) in northern Italy, where he was killed at the Battle of Marsaglia, October 1693.

This left the second son, Meinhard. He had accompanied his father on his military mission in Portugal in the 1660s, then back to France where he rose to the rank of maréchal de camp in 1678; he also accompanied his father and brother to England in 1689, and was named a general of the cavalry, commanding a wing of the army of William of Orange at the Battle of the Boyne. In 1691, Meinhard was named Commander-in-Chief while William III was abroad on the continent fighting in the Nine Years War. To raise his profile to help him maintain such a lofty command, in March that year he was created Duke of Leinster (with subsidiary titles Earl of Bangor and Baron of Tara) in the peerage of Ireland—in other words, the title got him a seat in the Parliament in Dublin, but not in London. Two years later, however, he succeeded his younger brother as Duke of Schomberg and thus did get a seat in the English House of Lords. As noted above, the Dukedom of Leinster was only the second dukedom created in the Irish peerage (the other being Ormonde, created for the Butlers in 1661). It would be good to dig into Irish archives to see if any lands were given to the new duke as part of this creation—but it did not survive very long. After he served once more as Commander-in-Chief for an army sent by Queen Anne to invade Spain via Portugal in the War of Spanish Succession—in which he was unsuccessful and disgraced—he died in 1719 and both ducal titles, Schomberg and Leinster—went extinct. Leinster as a dukedom is much more well known in its second creation, in 1766, for the richest family in Ireland, the Fitzgerald earls of Kildare. But that is a different story.

Before he died, Meinhard Schomberg re-established some of the family links with the Palatinate. After his first wife Barbara Luisa Rizzi died, in 1682 he married a woman called Raugravine Karoline von der Pfalz. The raugrave/raugravine title was given to the second family of the Elector Palatine Charles Louis (eldest son of Frederick V and Princess Elisabeth of England and Scotland), whose second marriage to one of his wife’s ladies-in-waiting, Luise von Degenfeld, was deemed unequal (and possibly bigamous, since he wasn’t quite divorced from his first wife). These children thus had royal blood, but were not legally capable of succeeding to the Electoral throne (or ultimately to the British throne). Karoline bore Schomberg a son, Charles Louis, who used the courtesy title ‘Marquess of Harwich’, but died at age thirty in 1713 before he could succeed to the ducal titles. Of the daughters, a younger daughter, Mary, married a cousin, Christoph von Degenfeld, and their descendants used the surname Degenfeld-Schonburg, which continues today. The oldest daughter, Frederica, Countess of Holderness by marriage, assumed (by some accounts, not by others) the title Countess of Mértola, then passed claims to it on to the Osborne family (dukes of Leeds), then in the mid-19th century to the Pelham family (earls of Yarborough). Since 2013 it is held (theoretically) by Lady Anthea (Miller) Lycett, who is also a co-heiress to two ancient English baronies, Conyers and Fauconberg.

Although neither of the Schomberg families left much of a built legacy in France, this last Duke of Schomberg did commission buildings in England. In 1694, the Duke purchased and redeveloped Portland House on Pall Mall, and renamed it Schomberg House. By the mid-18th century it was divided into three parts and developed for different purposes (flats, shops, residences for artists) but retained the name. In the 19th century it housed some of the War Office, and parts of it were demolished. Today only the façade remains.

About 20 miles outside London, towards the Chiltern Hills, the Duke built Hillingdon House in 1717, as a hunting lodge. After his death it passed to the Watson-Wentworth family (the earls, later marquess, of Rockingham). It was destroyed by fire in 1844 and rebuilt in a very different style. Since 1917 it has housed a station of the Royal Air Force.

Finally, we travel back to Saxony and the third family von Schönburg. This family may have had the same origins as those based in the Schönburg castle on the River Saale, but across the 13th to 15th centuries consolidated their holdings to a group of castles and fiefs on the upper valley of the Zwickauer Mulde river, which flows northwards into the Elbe. This region came to be known as ‘Schönburger Land’, a territory that stretched south towards the mountainous border between Saxony and Bohemia.

These lands were next door to the similarly sized territories of the House of Reuss which eventually became an independent principality within the Holy Roman Empire, but that outcome was difficult here since the Schönburg lands fell into different jurisdictions, in Saxony, Thuringia and Bohemia, giving them different status in each, a different voice in each local assembly, and limited ability to consolidate into a ‘state’. For example, they built a ‘Neuschönburg’ on a conical hill in northwest Bohemia, in the Egertal (the valley of the Ohře in Czech, and the ruined castle is today called Šumburk). This passed out of their hands by the early 17th century however.

One of the earliest Schönburg castles, Glauchau became the core property for the ‘comital branch’, that is, the one that did not become elevated to princely status. This was followed by Castle Lichtenstein (1286), Castle Waldenburg (1378), and Castle Hartenstein (1406). These names certainly reflect the forests and hills of this territory on the edge of the Ore Mountains (Erzgebirge): “light stone”, “forest castle” and “hard stone”. More estates still were added in the 16th century, notably the dissolved Priory of Wechselburg. The Schönburger Land ran roughly north to south from Waldenburg to Hartenstein, with Glauchau in the middle. All of these lordships were kept in one branch of the family or another for centuries, until the confiscations by the East German state in 1945 (a total loss estimated at over 30,000 square miles).

Lichtenstein Castle is perched on a hilltop overlooking the Zwickauer Mulde valley. It is mentioned as a lordship as early as 1212, given by the Emperor to the King of Bohemia (thus making its feudal position complicated later on), then leased by the latter to the Schönburg family. It was destroyed and rebuilt several times over the centuries, taking its current form in the middle of the 17th century. In 1797 a family crypt was built here and it houses several generations of the family. After 1945 it was used as a Catholic charity retirement home, until 2000 when it was re-acquired by the Schönburg family; in 2014 the local government forced its resale to developers and there is a strong local town historical group working to restore the largely decayed building.

Hartenstein and Stein castles, to the south, have had a somewhat better recent fate. Built only about a mile apart, Hartenstein on a hilltop and Stein down in the valley, both have been held by the Schönburgs since the early 15th century. Hartenstein was initially built in the 12th century to guard the roads into the mountains with its rich minerals. It was created a county in 1323 (like Lichtenstein a fief of the King of Bohemia). Part of the County was sold to the Elector of Saxony in 1559. About the same time, the old castle was rebuilt in a Renaissance style—three hundred years later it was remodelled along neo-gothic lines. It was one of the grandest castles in the region until it was nearly completely destroyed by American bombs in April 1945. Left a ruin, it has been repurchased by the Schönburgs, and since 2002 there have been efforts to preserve what remains and partly rebuild its structures.

In nearby Stein, the castle survived the war and the Communist era and is once again lived in by the Hartenstein branch of the family, after serving as a local history museum from 1954 to 1996. This structure is a fascinating complex of architectural styles, with an upper castle dating from the early 13th century and a lower castles from the late 15th century. Although it was also acquired by the Schönburgs in 1406, it was held by vassals until the mid-17th century. From 1702 it formed a separate lordship for a junior member.

Like all Germanic noble houses, there were divisions and subdivisions. One of the biggest of these came in the 1530s, when there was a basic division between the Glauchau line and the eventual princely line, with Waldenburg and Hartenstein as main seats; and these two were divided between two lines in 1569. All branches of the family were elevated to the rank of count in 1700. In 1740, an agreement was reached with the Elector of Saxony in Dresden that recognised his suzerainty over several of these fiefs that had previously been held directly from the Emperor. In return the Saxon estates promised to assure legal and military guardianship in these areas.

Then in 1786, Count Otto Karl von Schönburg-Waldenburg established primogeniture as the ‘house law’ in anticipation of the extinction of the line of Schönburg-Hartenstein, which occurred later that same year. As a result of this increased landholding, the Holy Roman Emperor created him Fürst von Schönburg in 1790, with the rank of ‘Serene Highness’. His main contribution to the family’s estates was the development of Grünfeld Park at Waldenburg, in the 1780s.

The strange hybrid vassalage of the Middle Ages continued even in the 18th century, with Hartenstein being a fief of the Elector of Saxony, while, until 1779, Waldenburg and Lichtenstein were fiefs of Bohemian Crown and thus subject to the Emperor in Vienna.

Though he was elevated to the rank of prince of the Empire, the family had little time to create a genuine state within the Empire before it was all dissolved in 1806. The Principality of Schönburg was mediatised, meaning the dynasty was still ranked as ‘princely’, but they held no actual sovereignty, its lands being more fully integrated into the new Kingdom of Saxony—though retaining special rights for several more decades. The 1st Prince had already died, in 1800, and his eldest son, Otto Viktor became the 2nd Prince. Otto Viktor and his brother Friedrich Alfred both pressed the leadership of the Confederation of the Rhine for recognition as a member state, then again lobbied the Congress of Vienna of 1814-15 to get their state recognised as independent in the post-Napoleonic world, to no avail. By this point, the brothers had already turned on each other: the Emperor had never formally recognised their father’s proclamation of primogeniture, so in 1813, the 2nd Prince renounced ownership of Hartenstein, keeping Waldenburg (the richer half) for himself, creating the two princely lines that survived into the modern era.

Otto Viktor, now called either the 2nd Prince of Schönburg or the 1st Prince of Schönburg-Waldenburg, retired from military service (he had fought in the Napoleonic Wars in the service of Saxony then Prussia), and now turned his attentions to politics, actively working with the Saxon legislature to create a new constitution for the Kingdom in 1831 (which guaranteed his dynasty two seats in the Saxon Upper House). He tried to create a state-within-a-state in Waldenburg, introducing reforms to local government, but his rule was so paternalistic verging on despotic, that his ‘subjects’ angrily rose up during the 1848 Revolution and burned down Waldenburg Castle. He died in 1859, leaving a very large family including several sons who founded a number of sub-lineages.

The 2nd Prince acquired a residence worthy of princes in the capital of the Kingdom of Saxony, Dresden. The Palais Schönburg, built in the 1750s in the old town not far from the royal castle was owned until the early 19th century by the counts von Vitzthum. It was demolished in 1885 when this part of the city was re-laid out for wider streets

The 3rd Prince of Schönburg-Waldenburg, Otto Friedrich, extended the family’s reach outside of Saxony, acquiring many more estates in the mountainous far west of Bohemia, notably imperial forestland near the spa town of Marienbad (today’s Mariánské Lázně). Here he built a hunting lodge, Glatzen (Kladská), and set about reforesting the land and developing it for forestry and tourism. He also purchased (1835) the very cute Rothlhotta castle, on a rock in a lake (today’s Červená Lhota). He remained active like his father in the politics of the Kingdom of Saxony, mostly in defence of the last shreds of autonomy his family enjoyed in his hereditary estates. Nevertheless, the last rights of Schönburg sovereignty were lost to Saxony in 1878, though the family was permitted to keep the rank of Serene Highness.

Otto Friedrich was succeeded in 1893 by his grandson, Otto Viktor II, since his son had died a few years before aged only 32. The 4th Prince was thus only 11 when he became head of the family. As he grew to maturity, like many wealthy aristocrats of his day, he travelled the world and became a collector. Between 1907 and 1910 he journeyed extensively in the Middle East and East Africa, bringing back numerous objects for a museum he established at Waldenburg. He served at a royal court, though not in Dresden, but in Potsdam for the German Emperor in the Life Guards. In the Spring of 1914, the Prince of Schönburg was active in supporting the candidacy and installation of his sister, Princess Sophie, and her husband Prince Wilhelm of Wied, in their new role as Prince and Princess of Albania, in that country’s first steps towards independence from the Ottoman Empire. It was not a success, and they were driven out by September. By that point, of course, World War One had broken out, and the 4th Prince of Schönburg-Waldenburg was amongst the first casualties on the Western Front.

The Prince and Princess of Wied had a daughter, Princess Marie Eleonore, who married a cousin, Prince Alfred of Schönburg-Waldenburg, from a second line descended from the 2nd Prince (Hugo, d. 1897). This branch was established at Castle Droyssig, but went extinct in the male line after Alfred’s death in 1941 and that of his father in 1945. This castle, rebuilt by the counts von Hoya on the site of an ancient provostry of the Order of the Holy Sepulchre, was acquired by the 2nd Prince in the 1830s and given to his son Hugo. The family installed a bear pit in the moat in the 1850s, and even after the family was dispossessed of the castle in 1948, the bears remained, or rather, were reinstated (in 1955). The ‘Bärenzwinger’ is still a local tourist attraction, and after it fell into disrepair, it was renovated and bears reintroduced in 2003.

The 4th Prince, Otto Viktor II, was succeeded by his brother, Günther, who endured the dismantling of the German Empire and the Kingdom of Saxony in particular—in 1918, his family were the largest landowners in Saxony after the royal family itself. In the two decades that followed, he made Waldenburg Castle a centre of art and culture, and became President of the German Art Society in Berlin. The 5th Prince was arrested with the Communist takeover in 1945 and interred in a camp on the island of Rügen in the Baltic, then escaped to the British Zone. Estates and castles in both East Germany and Czechoslovakia were confiscated. He lived in Celle for several years, then the United States. Returning to Europe in 1957, he died in 1960 in Salzburg. He had no children, so passed his inheritance to a second cousin.

Wolf, 6th Prince of Schönburg-Waldenburg came from a branch established by his grandfather, Prince Georg, another younger son of the 2nd Prince. Georg had served as Adjutant-General of the King of Saxony, and acquired the castles of Hermsdorf and Guteborn in Upper Lusatia as his portion of the succession, which became the seat of this branch. This hilly wooded area northeast of Dresden is crowded with castles built by the nobility in the 16th and 17th centuries. Guteborn remained a smaller residence while nearby Hermsdorf was transformed in the 1730s into a more glamorous baroque schloss. Both were acquired by the counts von Hoya in the 18th century, then passed to the Schönburgs by marriage in the 19th. Guteborn Castle became much more closely associated with the monarchy of Saxony in November 1918 when the last king, Frederick Augustus III, took refuge here during the revolutions that followed the collapse of the German Empire. He signed his abdication here too. Due to the castle’s association with the monarchy, after the Schönburg family were pushed out in 1948 by the Communists, they blew up the building entirely. Only a round chapel and the castle’s moat remain. Hermsdorf was transformed into a nursing home, so its interiors were mostly destroyed. Today it is owned by the local municipality.

The 6th Prince died in 1983 leaving only three daughters; his brother Georg also had daughters (though one married very well, to Archduke Franz Salvator, of the Tuscan line of the House of Habsburg) and died the year before; their youngest brother Wilhelm had died in 1944, so the succession passed to a nephew, Ulrich (b 1940). He has a daughter, so his heirs are his brother Wolf and his nephew Kai-Philipp (b. 1969). The latter is divorced and has no children, so this princely title may end unless it is allowed to pass to distant cousins in the next branch over, whose status is challenged.

These are the descendants of yet another son of the 2nd Prince, Ernst (d. 1915). Prince Ernst’s son Friedrich Ernst (d. 1910) made a very good marriage into the highest rungs of European royalty, though politically ‘hot’: Princess Alice of Bourbon, daughter of the Carlist Pretender to the Spanish throne, the Duke of Madrid. By Carlist standards she was an Infanta of Spain, but by those who supported King Alfonso XIII she was not. The young couple was married in 1897 and almost immediately squabbled over money—she later claimed she’d been forced into the marriage; news headlines spread gossip that she ran off with her footman, and within a few years they had an annulment. This meant that her husband’s family tried to deny the legitimacy of her son, Karl Leopold, though he was born during the marriage. Karl Leopold later moved to Tahiti where he had several children, also before he married his wife. So there is an heir, Vetea-Pierre (b. 1941), but it’s doubtful the family would allow him to succeed. Princess Alice did remarry, and moved to Florida.

The second major branch of the princely house of Schönburg, based in Hartenstein, and its adjacent castle (their seat), the Castle of Stein, was established in the family division of 1813. Friedrich Alfred, 1st Prince of Schönburg-Hartenstein, rebuilt Hartenstein Castle in 1820 in a neogothic style. He died in 1840, and though the princely title went to his younger brother, Heinrich Eduard, by law, the Hartenstein estates were re-divided between surviving siblings, meaning the eldest brother—the Prince of Schönburg-Waldenburg—was now owner of Waldenburg and half of Hartenstein. Very complicated. Did this mean he now had one and a half seats in the Saxon legislature?

The 2nd Prince of Schönburg-Hartenstein moved his branch of the family into the orbit of Habsburg Austria, becoming Catholic in the process (in 1822), and notably purchasing a grand palace in Vienna in 1841, near the Belvedere Palace. The Palais Schönburg, originally built in the early 18th century by the Starhembergs, remained their main urban seat until it was sold in the 1970s to a Viennese bank—restored in 2007 it is now used for events.

This branch of the family’s move to the south is indicated in the family tree by multiple marriages into the highest Viennese aristocracy: The 2nd Prince married Princess Pauline von Schwarzenberg in 1817 followed soon after her death by her sister Ludovika. His son Alexander married Princess Karoline von und zu Liechtenstein in 1855 bringing that family’s characteristic name Alois into the family for the first time for their son.

Heinrich Eduard was succeeded in 1872 by his son, Alexander, the 3rd Prince, who was a diplomat and a politician in the Bohemian local legislature and later in the Imperial House of Lords.

In 1896, he passed the title and estates on to his son Alois, the 4th Prince of Schönburg-Hartenstein. The 4th Prince was even more active in Austrian society and military affairs than his predecessors: in 1899 he became President of the Austrian Red Cross (a post he held until 1913), and in Spring 1918, the Emperor Carl promoted him to Colonel-General in the imperial army with the task of keeping order in the increasingly chaotic capital—he arrested strike leaders and army deserters in particular. That summer Schönburg led one last push of the Austrian army into northern Italy and suffered a terrible defeat. Unlike many former nobles, he kept his hand in affairs in the establishment of the Austrian Republic, and in 1934—as a now very experienced statesman—was temporarily Minister of Defence (March to September). In the years that followed, Alois von Schönburg was an avid supporter of the autonomy of Austria and worked to block the rise of National Socialism. He died at Hartenstein in 1944.

Since then the heads of the junior princely branch have been very quiet: the 5th Prince, Alexander, died in 1956, and was succeeded by his grandson, Aloys (his own son Aloys having died in Prague in May 1945 from battle wounds—in fact, four of the sons of the 5th Prince were killed in the war, two of them just teenagers. The 6th Prince lived in Munich and died before he reached thirty in 1972 and was succeeded by his uncles who had remained in Vienna, Hieronymous (d. 1992) and Alexander (d. 2018). The current 9th Prince is the latter’s son, Johannes (b. 1951). The family continue to intermarry with the old aristocracy of the Austrian Monarchy: the 8th Prince married a Windisch-Grätz princess, while the current heir, Prince Aloys Louis (b. 1982) recently married a Beaufort-Spontin duchess.

There are numerous members of the Schönburg-Hartenstein branch, as there are also of the branches of the Schönburg-Glauchau counts. Though they held a lower rank, this branch an even more impressive array of castles and palaces in this corner of Saxony, some of which have been re-acquired and restored. 19th-century German history is littered with counts and countesses from this branch. The most famous member in recent years is the colourful woman known in the press as the ‘punk princess’ in the 1980s, Princess Gloria of Thurn und Taxis, born Countess Gloria von Schönburg-Glauchau in 1960. Her brother, Count Alexander, is the head of the comital branch and a prominent journalist.

(images Wikimedia Commons)