Who is a current British duke whose surname is that of another ducal title, but whose ancestors’ surname was the one that is now the title of the current dukedom? Confused? What British dukes are royal yet not royal? Peers fifth in precedence amongst English non-royal dukes? The dukes of Beaufort. Whose house gave its name to a sport that since 1992 has been part of the Olympic Games? And also so closely connected to hounds and horses?

The Beaufort title was created in 1682 at a time when King Charles II was concerned with extending the ‘majesty’ of the Stuart bloodline by raising all those with this blood, legitimate or not, to a status above the rest of the nobility. He did this by making use of the then still rare ducal title, notably for his (or his brother’s) illegitimate offspring (Richmond, Saint Albans, Grafton, Berwick and so on). But the duke of Beaufort was not a Stuart, nor was he a Tudor—his family was a curious holdover from the dynasty that had ruled England in the Middle Ages: the Plantagenets. But choosing a ‘surname’ was tricky: Plantagenet was perhaps too obvious, and while Beaufort had been used by this family in the 15th century, when they were dukes of Somerset, by the 16th century their (illegitimate) descendants used the name Somerset instead. Meanwhile, the Somerset ducal title itself was now already in use by another family, the Seymours. It is confusing indeed! So instead of Beaufort dukes of Somerset, we will now have Somerset dukes of Beaufort. An even further twist enters the picture when considering that Beaufort itself was a place in France, one that had not been held by any English family since the 14th century, and had instead become a completely separate dukedom, held first by the illegitimate offspring of King Henry IV, Bourbon-Vendôme, then by one of the grandest aristocratic families in France, Luxembourg-Montmorency. So in the eighteenth century, it was possible for an English Duke of Beaufort to travel to France and meet another Duke of Beaufort. What’s more, if these two dukes journeyed to Brussels, they might even have met a third Duke of Beaufort (-Spontin), a Belgian title which took its name from a castle in the Ardennes.

The 18th-century English dukes of Beaufort were proud to claim a direct patrilineal link to the Plantagenets, and continued to do so into the 21st century—at least until science reared its ugly head. During the DNA testing of the remains of the last Plantagenet king, Richard III, in 2014, scientists announced that there had been a ‘genetic disconnect’ somewhere in the 18th century—ie, somebody lied about paternity at some point. But at least culturally and socially, the dukes of Beaufort of today represent the last of the Plantagenet dynasty in England. And as a ducal family in general, they have certainly been able to maintain this semi-royal status, as one of the wealthiest landowners in the United Kingdom with their own recognised livery—blue and buff—in the world of hunting and horse racing, and a palatial residence and near princely status in the counties of the southwest—Gloucestershire and Herefordshire—and across the border into Monmouthshire in South Wales.

The Beaufort story starts in France, where a small, but apparently beautiful, fortress in southern Champagne was called the ‘bellum forte’ or beau fort. This formed the core of a lordship from at least the 10th century, and was held by the powerful noble Broyes family who controlled much of this region on behalf of the Counts of Champagne. It was inherited by the Counts of Rethel (from northern Champagne) in about 1200, then was sold in 1270 to Blanche of Artois, wife of the Count of Champagne. Blanche’s second husband (from 1275) was Prince Edmund of England (known as ‘Crouchback’), the younger brother of King Edward I. Edmund was also Earl of Lancaster, so the association of Beaufort with the House of Lancaster began, as Blanche took the lordship as part of her widow’s dowry and transferred it to the children of her second marriage: her third son, John, was specifically called Lord of Beaufort, but when he died in 1317 it returned to the general pool of Lancastrian possessions. The 4th Earl of Lancaster, Henry, was raised to the rank of Duke in 1351, and his two daughters included Beaufort in their dowries, notably the second daughter, another Blanche, who in 1359 married John of Gaunt, a younger son of King Edward III who was re-created Duke of Lancaster in 1362.

By this time the Hundred Years War was raging in France and possessions of English royals were confiscated by the French Crown. Sources conflict at this point, as some say the castle and lordship of Beaufort was confiscated by King Charles V in 1369, while others claim that John of Gaunt’s children by his mistress Katherine Swynford were born in Beaufort, or at least the eldest, John, in about 1372, explaining why they were given ‘de Beaufort’ as a surname. More informed sources consider this unlikely.

We’ll turn to the children of Katherine Swynford, and their unique status, next, but first we can finish the French side of this story. The seigneurie of Beaufort, now a property of the French crown, was given out numerous times to various supporters over the next two centuries: to the Duke of Burgundy, to the Duke of Nemours, to Charles of Anjou; in 1477 it was elevated to the status of a county for a royal councillor, Thierry de Lenoncourt, then retained this status when restored to the Duke of Nemours. It was given in 1507 to the King’s cousin, Gaston de Foix, then to the latter’s sister, the Queen of Aragon, Germaine de Foix. And on and on to various French aristocrats at the Valois court.

In 1554, the family of Luxembourg-Brienne (who owned much of this area of Champagne) ceded the seigneurie of Beaufort to François de Clèves, Duke of Nevers (who was also Count of Rethel, so that Champenois link remained), whose daughter Catherine, Duchess of Guise, sold it to Gabrielle d’Estrées, the famous mistress of King Henry IV, in 1597. The county of Beaufort was then legally joined to several adjacent lordships and erected into a duchy-peerage for ‘la Belle’ Gabrielle and for her son, César de Bourbon, born three years before. César was at the same time created Duke of Vendôme (the old Bourbon patrimony), and in 1599 inherited everything from his mother upon her untimely death (some say just before King Henry married her, which would have made Vendôme the dauphin of France—but that’s another story). In time, while César’s first son became Duke of Vendôme, his second son François was ‘advanced’ by the King to the rank of Duke of Beaufort so that he could make use of its peerage to take a seat in the Parlement of Paris. Beaufort was a famously popular rebel leader during the civil war known as the Fronde, given the nickname ‘Roi des Halles’ (King of the Marketplace’), then reconciled with the monarchy and served as a commander in the armies of Louis XIV. This over-the-top colourful figure died leading a heroic if foolhardy charge against impregnable Ottoman defences at Candia in Crete in June 1669—his body was never recovered.

The ducal title passed back to the Vendôme family; the last duke, Louis-Joseph de Bourbon, then sold it in 1688 to Charles-François de Montmorency-Luxembourg, son of the Marshal de Luxembourg. In 1689 Beaufort was re-erected as a duchy-peerage, but this time taking the name Montmorency. This was due to the fact that the Montmorency family no longer owned the lordship of that name (having been confiscated by the Crown in the 1630s); it also consolidated this family’s landholdings in the region of Champagne, as their other duchy (known as ‘Luxembourg’ or ‘Piney’) was literally next door to Beaufort. The dukes of Montmorency (Beaufort) remained prominent at the court of France throughout the 18th and 19th centuries. The village and the remains of its ancient beau fort took on the name Montmorency, which it kept until 1919, when it was renamed Montmorency-Beaufort.

Returning to the English Beauforts, we can look at one of those fascinating medieval personages who continued to blend the English court with life on the Continent. Catherine de Roët was the daughter of a knight from Hainaut in the Low Countries, who came to England in the suite of Philippa of Hainault, wife of Edward III, in 1328. She was later placed in the household of Blanche of Lancaster, wife of John of Gaunt (the King’s third son) and was given the responsibility of looking after their daughters, especially following the Duchess of Lancaster’s death in 1368. Catherine (or Katherine) was at this time married to Hugh Swynford, one of the knights in John of Gaunt’s retinue. It was also about this time that her sister Philippa married another courtier in Queen Philippa’s household, the poet Geoffrey Chaucer. Katherine became the mistress of John of Gaunt (remarried in 1371 to the Infanta Constance of Castile). Four children were born in the next decade: John, Henry, Joan and Thomas.

Katherine Swynford continued to serve as a lady-in-waiting in the household of the new Duchess of Lancaster, and later in that of Mary of Bohun, married to John of Gaunt’s son Henry of Bolingbroke in 1381. Finally, in 1396, the Duke married his former mistress and obtained a papal bull retrospectively legitimising his and Katherine’s children, giving them the name ‘Beaufort’. But why? It seems strange to me to choose a fairly obscure lordship in Champagne that was no longer part of the Lancaster landholdings. Tudor historians dismiss the idea that it was named for the lordship of Beaufort in Anjou, but this would make more sense to me, since Anjou was in fact the historic place of origin for the Plantagenet dynasty, and Beaufort castle, part of the dowry of John of Gaunt’s ancestress, Queen Isabella of Angoulême (wife of John I), continued to be fought over, frequently, in the Hundred Years War. The County of Anjou had been lost to the Plantagenets in the first years of the 13th century, but it was always a place deemed worthy of re-conquest by the English monarchs, so the naming a child ‘Beaufort’ would have more symbolic value.

John of Gaunt’s nephew, King Richard II, confirmed the legitimacy of these Beaufort children with an act in Parliament in 1397. But a few years later, in 1407—Bolingbroke having overthrown his cousin Richard and crowned himself as Henry IV—another legal confirmation was made of his half-siblings’ legitimacy, but this time with the added clause ‘excepta dignitate regali’. This meant that although his half-siblings were legitimate and thus able to legally inherit property (and had any social stain removed from their bastardy), they could not inherit the throne of England, the ‘royal dignity’. The exact validity of this proclamation has been debated by historians for centuries—for example suggesting it was never formally presented to Parliament, so invalid as law—notably because part of the claims of the Tudor dynasty to the throne depended on the status of their Beaufort ancestors.

Richard II had already loaded down his cousins with titles and royal offices. The eldest, John de Beaufort, was created Earl of Somerset in 1397 shortly after the formal legitimisation, and given the offices of Lieutenant of Aquitaine and Warden of the Cinque Ports. He was even married to the King’s niece, Margaret Holland, daughter of the Earl of Kent. Later that same year, John was elevated further to Marquess of Dorset, only the second time this title had appeared in England. The second son, Henry, was named Bishop of Lincoln. Their sister Joan was honoured by the King raising her husband, Ralph Neville of Raby, to an earldom (Westmoreland), also in 1397. But when Henry IV took the throne in 1399, he deprived his half brother of his offices and the title Marquess of Dorset (with the King apparently pronouncing that “the name of marquess is a strange name in this realm”). He remained Earl of Somerset, however, and in 1404 was appointed Constable of England. His brother Bishop Henry was transferred from Lincoln to Winchester, and served for a year as Henry IV’s Lord Chancellor (1403-04).

Where did these early Beauforts live? They were initially raised in their mother’s house at Kettlethorpe in Lincolnshire (and thus close to the bishopric where second son Henry would initially be established). By the 1390s, John was given several manors in Somerset, which would in a sense form his earldom—lands formerly held by the Montague earls of Salisbury in the southern part of the county, near Yeovil. He and his brothers were also given lordships and manors in Northamptonshire, Derbyshire, Norfolk and elsewhere.

But in terms of a family seat, this might best be considered to be Corfe Castle in Dorset (so again connected to one of the main family titles). This was a royal castle, built initially by William the Conqueror and one of the earliest stone castles in England. It was frequently used as a residence for royal hostages and like the other main royal castle-prison, the Tower of London, was usually whitewashed giving the central tower a unique white appearance as it guarded a pass through the white chalk hills of Dorset. The Earl of Somerset was named Constable of Corfe Castle in 1407, and the family would be based here for the next half-century. The castle remained in royal hands until 1572 when Elizabeth I sold it to Christopher Hatton, whose heirs sold it in 1635 to the Bankes family. The Bankes were royalists who held this castle against Parliamentary forces longer than any in southern England, but ultimately were pushed out in 1645 and the castle’s defences ‘slighted’ (made indefensible). The family recovered the property, but left it a ruin for the next three-hundred years; in 1981 they gave it to the National Trust which undertook major renovations in 2008.

Not far to the north in Dorset, the Beauforts patronised an important collegiate church, Wimborne Minster, built by the Anglo-Saxons in the 8th century, and burial place of King Aethelred I. It was rebuilt by the Normans in the 11th century. The 1st Earl’s son, the 1st Duke of Somerset, would be buried here in 1444, and his grand-daughter, Lady Margaret Beaufort (mother of Henry VII), would build a family chapel here.

Meanwhile, in London, the family had power bases notably at the episcopal residence of the bishops of Winchester, Winchester Palace, in Southwark on the south bank of the Thames (which at that time, extraordinarily was within the diocese of Winchester). This great palace was built in the 12th century and survived until the 18th century when it was divided up into tenements and storehouses, then mostly burned down in 1814. Across the river, the Beauforts acquired a mansion in the City of London known as Cold Harbour (or Coldharbour or Harborough), located on a street of aristocratic mansions known as Upper Thames Street, near today’s Cannon Street tube station. It had once belonged to Alice Perrers, mistress of Edward III but was confiscated when she was disgraced and exiled in 1376. It was given to the Duke of Exeter whose niece Margaret Holland was married to John de Beaufort, and they took over the house from about 1401. It was later a favoured residence of Lady Margaret Beaufort during the reign of Henry VII. Coldharbour Mansion was later owned by the earls of Shrewsbury and was destroyed in the Great Fire of London of 1666.

By 1410, the 1st Earl of Somerset was well established, with lands and residences all over southern England. But he died suddenly in March of that year, aged only about 35. His son Henry became 2nd Earl, but was still in the nursery, aged 9. So Henry, Bishop of Winchester, became head of the Beaufort family. By the end of the reign of Henry V, he was one of the most powerful men in the Kingdom, serving again as Lord Chancellor (essentially head of government) in 1413-17, and then for the infant King Henry VI in 1424-26. Beaufort had also been named as one of the leaders of the Regency Council for the infant king in 1422, and when he retired as Chancellor was named a Cardinal (1426) and Papal Legate for Germany, Hungary and Bohemia (1427). With this latter charge he led an army in Bohemia against the Hussite heretics, but was badly defeated at Tachov. Cardinal Beaufort remained at the centres of power in England in the 1430s-40s, but now as just one of Henry VI’s many feuding advisors—he once again played a prominent role in arranging the King’s marriage with the King of France’s niece, Margaret of Anjou, in 1445, then died in 1447. This marriage brought the Beauforts a powerful ally at court, but in the long run much enmity from those who sought to undermine the Queen’s power over her husband and later son.

Meanwhile, the youngest Beaufort son, Thomas, had come of age: Henry IV had created him Earl of Dorset in 1412, and revived his older brother’s appointment as Lieutenant of Aquitaine. Dorset too had a stint as Chancellor of England (1410-12). In the next reign, Henry V made him Duke of Exeter, in 1416—the title held previously by the family of his sister-in-law, Margaret Holland (and re-created for them later)—and kept him close during his re-conquest of Normandy, 1418-19. The King named him ‘Count of Harcourt’ to encourage a sense of ownership in the old Norman dominions (which included the powerful stronghold of Harcourt). The Duke of Exeter was also a member of the regency council for Henry VI in 1422 and died in 1426, leaving no living children from his marriage to Margaret Neville of Hornby.

The Beaufort family thrived in the reign of Henry VI. The children of John, 1st Earl of Somerset, were a virtual second royal family, and at times came close to usurping that place entirely—something that caused the strong rivalry with the House of York and led in part to the Wars of the Roses. Henry Beaufort, the 2nd Earl of Somerset, had died as a teenager at the siege of Rouen in 1418, so it was his brother John who led the family in this reign. In 1421, he and younger brother Thomas went to France with their royal cousin Henry V. They fought at the Battle of Baugé, and both were captured. John remained in captivity for 17 years, and Thomas for six. When he was released, Thomas was created ‘Count of Perche’, with a similar design as above to inspire him to re-take that French county, while the youngest brother Edmund was created ‘Count of Mortain’ in Normandy. None of these titles (Harcourt, Perche, Mortain) were recognised by the French king. Thomas was killed in 1431 at the siege of Louviers, when Edmund took over command of the English army, and made a name for himself re-capturing the important port of Harfleur and delivering the besieged city of Calais. Meanwhile their sister Joan married the King of Scots, James I, who had been in captivity in England for nearly two decades—James was released upon their marriage in 1424 and he and Joan Beaufort returned to Scotland where she played an important political role for the next twenty years.

When the 3rd Earl of Somerset was finally released in 1438, he returned to England and was given command again in France, as Captain-General of Aquitaine and Admiral of the English navy. He proved to be a poor commander and presided over the loss of much of Aquitaine. Nevertheless, in August 1443 he was created Duke of Somerset and Earl of Kendal, and led another campaign to France, this time disastrously losing the English hold on Normandy. By this point, Henry VI had failed to establish himself as a powerful monarch, and his royal cousin the Duke of York’s influence was rising. The 1st Duke of Somerset died in May 1444, after only eight months of being a duke (though there are some indications he’d been named a duke as early as 1438). He left behind a widow, Margaret Beauchamp of Bletsoe, and an infant daughter, Margaret Beaufort, future progenitrix of the Tudor dynasty.

The Duke of Somerset’s brother Edmund, meanwhile, had been given a re-creation of the Earldom of Dorset in 1442—still based in its stronghold at Corfe Castle—then promoted to his father’s old ‘strange’ title, Marquess of Dorset. In 1444, he was named Lord Lieutenant of France, supplementing his brother’s near complete control there. When John Beaufort died in 1445, Edmund replaced him as 2nd Duke of Somerset (though formally not re-created until 1448). He forced the Duke of York out as supreme commander in France, and, allied with Queen Margaret of Anjou, functioned essentially as Henry VI’s prime minister from June 1450. He acted as godfather to the Prince of Wales at his baptism in 1453, and strongly hinted that he should be named the child’s heir and head of the House of Lancaster. The 2nd Duke of Somerset was no more successful in war than his brother had been, however—he was forced to surrender the Norman capital of Rouen, then lost all of Normandy by 1450, and the remaining strongholds in Aquitaine by 1453. In April 1454 the Duke of York ousted him from government and imprisoned him in the Tower of London (and spread rumours that the Prince of Wales was actually Somerset’s son), until the King regained his senses at the end of the year and released him. By the spring of 1455, however, England was at war with itself, and Somerset was killed by Yorkist forces at the Battle of Saint Albans.

The pretensions of the House of Beaufort that clashed so intensely with the House of York can be seen visually in their coat-of-arms: the golden lions of England quartered with the lilies of France, made different to the royal arms of England by a border of alternating blue and silver (known in heraldry as a ‘bordure compony’). These arms were supported by one of the most curious of heraldic animals: the ‘Beaufort yale’. A yale was a mythical beast, like an antelope but with tusks and horns that could swivel in any direction. Under the Tudors it became one of the ‘king’s beasts’ and can be seen in statue form today in front of Hampton Court Palace.

There were now two Dowager Duchesses of Somerset, both with Beauchamp as a surname (though from different branches). Duchess Margaret looked after her daughter Margaret by agreeing to her swift marriage in November 1455 (though she was only 12) to King Henry VI’s half-brother (who was already her legal guardian), Edmund Tudor, Earl of Richmond. Duchess Eleanor (daughter of the Earl of Warwick) was left with three sons and five daughters. In 1458, in an attempt at reconciliation, it was agreed by the Royal Council that the Duke of York should pay the widowed Duchess Eleanor and her children an annual pension of five thousand marks as compensation for the death of the their father. The eldest son, Henry, had just turned twenty and was now 3rd Duke of Somerset. He became the hope of the House of Lancaster, with the King slipping increasingly into madness and the Prince of Wales still a child. In 1459, Somerset was sent with a force to take the fortress of Calais from the Earl of Warwick, Richard Neville—his cousin via his great-aunt Joan and his cousin-in-law via his mother. Back in England, the Duke of Somerset was initially successful in battle, at Wakefield in 1460, then at the second Battle of Saint Albans in 1461. But a few weeks later he lost the Battle of Towton, and fled to France as York proclaimed himself king as Edward IV. Somerset’s titles were attainted by Parliament in December, but he was pardoned in 1463 and restored to his lands and titles. He nevertheless re-joined the forces of Queen Margaret in rebellion against Edward IV, but was defeated at Hexham in Northumberland in May 1464—he was captured by Yorkist forces and executed on the spot.

Brother Edmund now became 4th Duke of Somerset. He had lived in France since 1461, attempting to rally the French king to Margaret of Anjou’s cause. He was only recognised as duke by the Lancastrians since the title was once more attainted in May 1464. He returned with Queen Margaret to England in 1470, and was captured and executed after the Battle of Tewkesbury in May 1471. His brother John, known as the Earl of Dorset (again only recognised by Lancastrians) was also killed at Tewkesbury.

All that remained now of the House of Beaufort, so powerful just two decades before, was the Dowager Duchess Margaret; her daughter Margaret, Dowager Countess of Richmond, aka Lady Henry Stafford (her first husband Edmund Tudor had died in 1456, and Stafford would soon follow, later in 1471); the latter’s young son, Henry Tudor, living abroad at the court of the Duke of Brittany; and five married Beaufort women. The eldest of these, Eleanor, was the widow of the powerful Earl of Ormond—her daughters from a second marriage became major heiresses and took many of the Beaufort estates into the houses of Carey and Percy in the Tudor era. Anne married into the Paston family, famous for the ‘Paston Letters’ which are an invaluable source for students of the late 15th century; while Margaret was widow of the Earl of Stafford, elder brother of Sir Henry Stafford—making it a little confusing to have two Lady Margaret Beaufort Staffords. The more famous of these Lady Margarets was of course the mother of King Henry VII and the all-seeing dowager-grandmother until a few months into the reign of Henry VIII.

Lady Margaret Beaufort has featured prominently and with great vigour in recent television dramas about the early Tudors, and has been in archaeological news as well, with the rediscovery in December 2023 of the location of the ‘lost Tudor palace’ of Collyweston. The manor of Collyweston, in the northwestern corner of Northamptonshire (not far from Stamford, in Lincolnshire), was built in the early 15th century and granted to Margaret by her son shortly after his accession in 1485. She enlarged the house and arranged its terraced gardens in about 1500, and notably hosted the court in 1503 as part of the send-off arranged for her grand-daughter, Princess Margaret, on her way to marry the King of Scots. After Margaret’s death in 1509, Henry VIII gave it to his natural son, Henry FitzRoy, and later in the century it was given to Princess Elizabeth by her brother Edward VI, but not visited often. By the end of the century, it was leased to the Cecil family (whose seat, Burghley House was not far away), and though it was sold by James I to a royal servant in the 1620s and mostly dismantled in the 1640s, the estate once again passed to the Cecils, earls of Exeter by the end of the 18th century. By this point, almost all traces of the original house were gone.

This was the end of the powerful Beauforts of Somerset. But not the end of the House of Beaufort. The 3rd Duke of Somerset had a son, Charles Somerset, born of a relationship with Joan Hill in about 1460. In 1492, he made an excellent marriage, to Elizabeth Herbert, daughter of the Earl of Pembroke and heiress of his title Baron Herbert and of the chief seats of that family, Raglan Castle and Caldicot Castle, both in Monmouthshire in southeast Wales (see the Herbert family, dukes of Powis). The new Baron Herbert thus bore the arms of Beaufort, ‘bruised’ with a silver ‘baton sinister’ indicating his illegitimate birth, and overall the escutcheon of the Herberts, three silver lions on a divided red and blue shield. Adding to their already unique ‘Beaufort Yale’, the Somerset family arms had two other rather strange supporters which they picked up from the Herberts: a green wyvern on one side, a fairly common Welsh beast, and a curious silver panther with spots of various colours and bursts of flame coming out of its mouth and ears. Heraldic experts of the 19th century puzzled over this magical panther, equating it possibly to those seen on the continent in the Middle Ages, which were also spotted and had flames coming out of their mouth, thinking it might refer to ancient Greek texts that said that panthers had very sweet-smelling breath, which made all other animals—except the evil dragon—approach it, thus being a symbol of the sweetness of Christ. This panther is seen as one of the supporters of the royal arms under Henry VI, so perhaps it came to the Beauforts from there. The Somerset family would keep the division of the coat of arms between Beaufort and Herbert until the 1620s, when the latter was dropped.

Of the major estates gained by the Somerset-Herbert marriage, the seat of the family became Raglan Castle. Raglan had long been an important Norman border fortress between the English county of Hereford and the untamed wilds of South Wales. Built soon after the Conquest, it was held by the Bloet family for two centuries until it was purchased in 1432 by a Welsh nobleman on the rise, William ap Thomas, who rebuilt the castle to more modern fortification standards. His son William took the surname Herbert, supported the Yorkist cause, and was created Baron Herbert of Raglan in 1461 and Earl of Pembroke in 1468. He had greatly expanded Raglan as befitted his new status, but was suddenly executed in 1469 after falling out with the Earl of Warwick. He had married his son and heir to the Queen’s sister, Mary Wydville, but this was not enough to recover favour, and ultimately the 2nd Earl of Pembroke had to surrender his father’s earldom to the Crown. When he died in 1491, he left an orphan, Elizabeth Herbert, who married Charles Somerset and in a way joined together Lancastrian and Yorkist factions—a very good Tudor precedent.

Raglan Castle remained the seat of the Somerset-Herberts in the 16th century and was developed as a great aristocratic seat with art collections and a renowned library. After the Civil War, the republican government of the 1650s decided to ‘slight’ it (like Corfe, above), and after the restoration of the monarchy, the family decided not to rebuild it—instead they focused on Badminton (below). In the mid-18th century the Somersets decided to slow the decay of the ruin and turned it into a tourist site; it was fixed up a bit in the 19th century, and the great hall given temporary roof for entertainments and a royal visit. In 1938 Raglan was donated to the Commission of Works, which since the 1980s is called Cadw, the Welsh equivalent of English Heritage. It remains one of the great wonders of medieval castle building in the UK.

Near to Raglan Castle is Saint Cadoc Church, which became a burial site for the Somerset family. Initially built by the medieval de Clares—powerful lords of this area between England and Wales, it was expanded in the early modern period by the Herberts and Somersets, notably with the addition of the Beaufort Chapel in the mid-16th century. The church was restored by the 8th Duke of Beaufort in the 1860s, and a Lady Chapel added. By this point, however, the main family burial area had shifted to Badminton.

The other main Herbert castle inherited by the Somersets was Caldicot in Monmouthshire. Based on the coast of the Seven estuary, it guarded roads to south Wales, and had initially been built by the Norman representative of the Crown here, the Sheriff of Gloucester, in the 1070s. The Bohun family, earls of Hereford, built a more extensive castle in the 1150s, and when their family estates were divided between two members of the royal family (Thomas of Woodstock and Henry of Bolingbroke) it entered the royal domain, but was given to the Herberts as stewards. The Somersets did not use Caldicot Castle much, and by the 18th century it was a ruin. Sold in 1857 to the Cobb family, who restored parts of it, it was held by them until sold to Chepstow District Council in 1964, and opened as a museum.

Charles Somerset’s title to these Herbert estates was confirmed when he was called to Parliament as Baron Herbert of Raglan, Chepstow, and Gower in 1506. Then in 1514, Henry VIII raised his cousin in rank to Earl of Worcester and Lord Chamberlain of the Household. This last post meant it was he who was responsible for making much of the arrangements of the famous Field of the Cloth of Gold in 1520. By then Elizabeth Herbert had died, so the Earl re-married, Elizabeth West then Eleanor Sutton of Dudley, firmly tying his family to the rising ‘new men’ of the Tudor era.

His son Henry, 2nd Earl of Worcester, added to the family’s lands in Monmouthshire by obtaining the newly dissolved Tintern Abbey in the Wye Valley. Unlike some of his peers, he did not modify the buildings of this ancient Cistercian monastery to form a new country house, but stripped the building for parts (notably the lead roof) and let the rest fall to ruin—it became one of the most ‘romantic’ ruins in England, celebrated in poetry and music.

The 2nd Earl’s marriage in 1514 is quite interesting: Margaret Courtenay, daughter of the Earl of Devon and of Princess Catherine of York, brought not just the usual noble dowry, but added still more Plantagenet blood to the Somerset clan. But they had no children (though some genealogists say his eldest daughter Lucy was Catherine’s daughter, and took her Plantagenet blood to marriage to John Neville, 4th Baron Latimer, step-son of Queen Katherine Parr), and his second marriage, in 1527, to Elizabeth Browne, was less illustrious, though she had a Neville mother who herself had a Beaufort great-grandmother. There’s always a connection, and remember how twitchy the Tudors were about anybody with Plantagenet blood…

The 2nd Earl of Worcester was followed by his son, William, 3rd Earl, a supporter of Jane Grey—he survived her downfall and lived into the 1580s, and married two fairly insignificant women, thus ruffling no feathers. A younger son, Thomas Somerset, made more waves: a fervent Catholic, he had been a servant of Bishop Gardiner in the reign of Mary I, and was imprisoned for more than 25 years in the reign of Elizabeth I—the last stint (from 1585) for complicity in the plot of Mary, Queen of Scots. He died in the Tower in 1586.

The 4th Earl of Worcester rose to prominence again in the reign of James VI and I. He had got to know James VI of Scotland in the 1590s when he was sent to his court as an emissary of Elizabeth I. Once in England, James named his distant cousin (via Lady Margaret Beaufort) Earl Marshal, one of the most important positions at court, though after 1604 he had to share the office with six (later four) other courtiers as the King decided to put it ‘in commission’ to spread out the honour. In 1606, Worcester was created Keeper of the Great Park, an area southwest of London around the Tudor hunting lodge of Nonsuch. Here Worcester built his own house, Worcester Park House, which only stayed in the family a short time: it was bought during the Civil War by Col. Thomas Pride, and passed through various hands across the centuries before burning to the ground in 1948—hardly a trace remains.

In 1616, the 4th Earl rose to his highest position as Lord Privy Seal, an office he held for nearly ten years. He died in 1628 leaving two sons and a daughter who, in keeping with the theme of ‘Plantagenet blood’ in this blog, inherited a double dollop more from their mother, Lady Elizabeth Hastings, daughter of the Earl of Huntington and Catherine Pole—both of whom were descended from Plantagenet kings.

The 5th Earl of Worcester, Henry Somerset (known as ‘Lord Herbert’ as the heir) was not just someone with a lot of royal blood; he was also a Catholic. But he was one of the richest peers in England and Wales and a firm supporter of King Charles I to whom he lent a lot of money with which to raise a Royalist army. For this he was rewarded with an upgrade: the title Marquess of Worcester in 1642. He hosted the King at Raglan in June-September 1645, then surrendered the castle to Parliamentary forces in late 1646. He died in custody later that same year.

The younger son, Thomas, was also a favourite at the court of James I. He had been one of those English lords sent north of the border to announce the death of Elizabeth I in 1603, and when his father was named Earl Marshal in 1603, he was named Master of the Horse to Queen Anne of Denmark. In 1616 he married an Irish noblewoman, and in 1626 was given an Irish title, Viscount Somerset of Cashel. But he died in 1651 with no children. His sister was also a famous royalist: Blanche, Baroness Arundell of Wardour is known for having valiantly defended her home, Wardour Castle, in Wiltshire, in May 1643, with only 25 men and her maids holding out for a week against over a thousand Parliamentary troops.

The next generation saw another two sons: Edward became 2nd Marquess of Worcester, while his brother Thomas became a Catholic priest and a leader of the English Church abroad, as a nuncio for Pope Clement IX sent to England. He died in 1678 in Dunkirk. Meanwhile, the 2nd Marquess (while still ‘Lord Herbert’) raised a force of Welsh troops in 1643 to support the King and was created Earl of Glamorgan and Baron Beaufort of Caldecote in his own right. These troops were almost immediately abandoned however, and he was sent by the King to Ireland, where he worked—as a Catholic, and having an Irish wife—to negotiate an alliance with the Irish Catholic Confederates. He was accused, however, by the Royalists of granting too many concessions to the Irish, so he ended up joining them in their rebellion. He fled to France by 1645, then attempted return to England in 1653 but was caught and held for a year in the Tower of London. Restored to his honours by Charles II in the 1660s, he nonetheless preferred to stay away from court, working instead in his ‘laboratory’ where he developed some interesting engineering devices: a proto-steam engine, a hydraulic machine for irrigation, and more.

The 2nd Marquess had married twice, both to Catholics: Lady Elizabeth Dormer and Lady Margaret O’Brien. By his first wife he had a son, Henry (next), and two daughters: Anne was married to a Howard and was mother to the restored line of dukes of Norfolk; while Elizabeth re-connected her family to the Herberts in its junior line (the earls of Powis). These families were the apex of the Catholic nobility in Britain. Nevertheless they retained favour with the Stuarts, but did not cross the line when other Catholic nobles supported James II in 1688. So close was the family to the royal family that in 1646, Henry had been considered for marriage to the King’s daughter, Princess Elizabeth. But Henry went into exile and Elizabeth died in 1650. While abroad, he renounced Catholicism and became ‘acceptable’ to Lord Cromwell, and was elected as simple ‘Mr Herbert’ as an MP for Breconshire in 1654. He was involved in a royalist plot in July 1659, and was sent to the Tower until November. He was then sent by Parliament to Breda in the Netherlands as part of the delegation inviting Charles II back to England in May 1660. At the Restoration, Lord Herbert was appointed Lord Lieutenant of Gloucestershire, as well as for Herefordshire and Monmouthshire. The family estates were restored to him, not to his father. He continued to sit in Parliament (now as MP for Monmouthshire) until he succeeded as 3rd Marquess of Worcester in 1667.

At this point, the 3rd Marquess of Worcester started to develop a new seat for the family, Badminton, acquired from his cousin, Elizabeth Somerset (daughter of the Irish Viscount). The old manor in south Gloucestershire had been purchased by the 4th Earl of Worcester in 1612, and his son the Viscount started modernising it in the 1620s. The 3rd Marquess relocated here from Raglan, and already by 1663 was able to entertain the King and Queen here—over the next three hundred years, Badminton would serve as a nearly royal residence for this nearly royal family. The household at Badminton in the late 17th century, for example, was described as ‘princely’, with over 200 members of staff.

In the 1670s, the Marquess of Worcester was appointed Lord President of Wales and the Marches, which allowed him to exercise some of these semi-royal prerogatives on behalf of his distant cousin King Charles II. He built Great Castle House atop the old Monmouth Castle, 1673, as the seat for his office as Lord President. This building was later given over to the local judiciary, and later became a school, then regimental headquarters and now a museum.

As a Catholic, however, the Marquess of Worcester was drawn into some of the scandals of the time—he was accused of being involved in the Popish Plot, but nothing came of it, and was opposed to Parliament’s attempts to block the succession to the throne of the King’s Catholic brother James. In 1682, the King rewarded him by elevating him further in rank with by creating him Duke of Beaufort. He then served as one of the chief mourners for Charles II in February 1685 and bore the Queen’s crown at the coronation that followed in April. James II appointed the new duke Gentleman of the Bedchamber, and he was dispatched to the southwest during Monmouth’s Rebellion that summer, keeping the city of Bristol loyal to the Crown. He did this again in late 1688 as William of Orange’s troops were arriving just a bit to the south of Bristol in the Glorious Revolution. The Duke of Beaufort did not, however, go into exile like other supporters of James II, but he did support the idea of naming William III as regent, not king, in the Spring of 1689. Nevertheless, he did accept the decision made by Parliament, swore the oath to the new King and Queen, and received them at Badminton in September 1690.

Yet the 1st Duke of Beaufort was still suspected of disloyalty in the later 1690s, and even accused of being involved in a Jacobite plot in 1696. He increasingly stayed away from court and preferred to live at Beaufort House in Chelsea. Here his wife, Duchess Mary (born Mary Capell, sister of the 1st Earl of Essex), was becoming known as a gardener and collector. This house had been built by Thomas More in 1520 and was forfeit to the Crown upon his arrest in 1534. It was then given out as a London residence to various men like the French ambassador or ministerial families like the Paulets or the Cecils, and later court favourites like the Earl of Middlesex and the Duke of Buckingham. In 1677 it was acquired by the Marquess of Worcester from the Earl of Bristol. Chelsea was still an area of large gardens in the seventeenth century, and Beaufort’s neighbour was the famous collector, Sir Hans Sloane, who bought Beaufort House in 1737, and demolished it in 1739 to expand his own gardens. Only the name ‘Beaufort Street’ remains in the area.

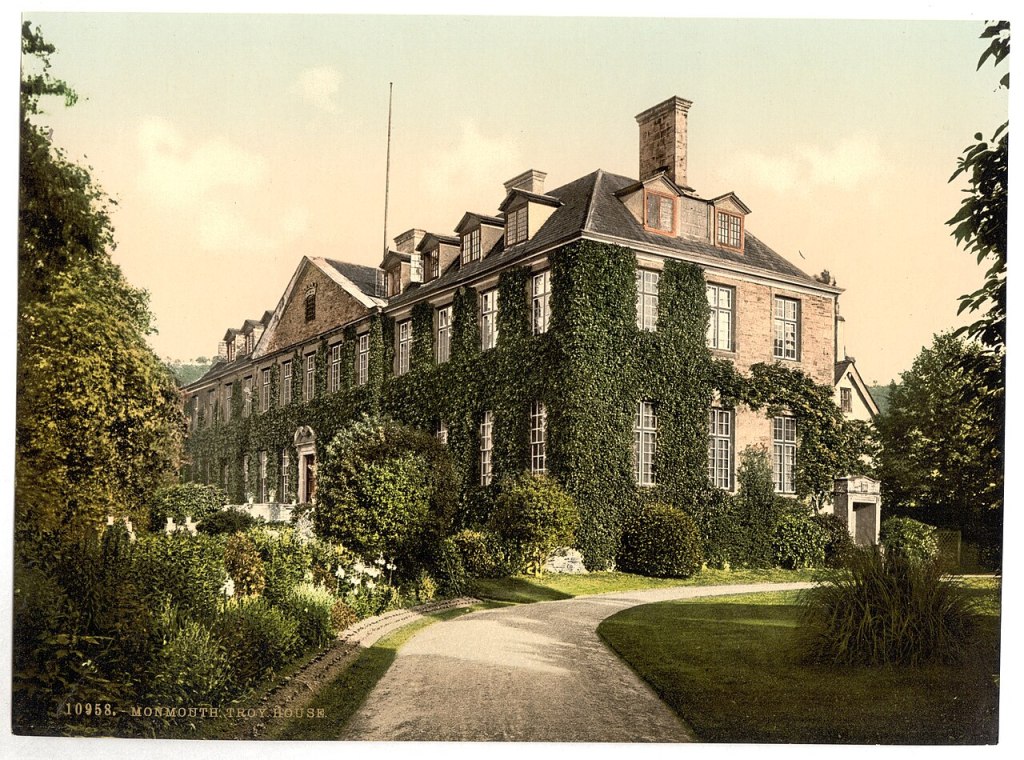

The 1st Duke of Beaufort died in 1700 and was buried in Beaufort Chapel in Saint George’s, Windsor, and later was moved to St Michael and All Angels church in Badminton, built in 1785. In addition to work done at Badminton, the Duke also developed another family property in this era: Troy House, a former property of the Herberts of Troy (an estate just south of the town of Monmouth), was restored in 1681-82 as a wedding present for his son and heir, Charles (known as the Earl of Glamorgan until his father’s elevation to the dukedom, then Marquess of Worcester). Troy House remained the residence for the heir to the dukedom until 1899 when it was sold, alongside many of the family’s Welsh estates, to nuns who created a convent school. It remained as such until the 1980s, and today sits as a mostly abandoned ruin, with developers struggling with local planning regulations to develop it into flats.

The 1st Duke of Beaufort was succeeded in 1700 by his grandson, Henry, since his eldest son Charles had died two years before. The 2nd Duke began the family’s long tradition of steady but fairly unremarkable service as Tory politicians in the 18th century. He married three times but left only two sons when he died in 1714. Henry, 3rd Duke Beaufort, spent a much longer time as duke, but was known mostly for social and cultural affairs rather than politics. He commissioned the Badminton Cabinet, for example, a set of exquisite wooden drawers made in Florence that sold in 2004 for 19 million pounds (to the Prince of Liechtenstein), making it the most expensive piece of furniture in the world. His other connection to the art world was through the marriage of his illegitimate daughter, Margaret Burr, to the painter Thomas Gainsborough (though this didn’t occur till the year after the Duke’s death). In a divorce trial scandal of 1742 the Duke did have to prove publicly that he could have an erection in order to disprove his estranged wife’s claims of impotence. A year later he was involved in an international scandal in which Jacobite peers were discovered to be encouraging the French government to support an uprising in favour of the exiled Stuarts, but he died in February 1745 before things really heated up.

The 3rd Duke’s brother, Charles, now the 4th Duke of Beaufort, was more directly involved in the Jacobite rising known as The ’45—he even hosted a secret visit of Bonnie Prince Charlie to London in September 1750—but the government never pursued him. He died in 1756, but in his short time as duke had contributed to the a significant makeover of the family estates. Badminton was given a new Palladian style in the 1740s, celebrated in grandiose paintings of the house and grounds by Canaletto, the famous Venetian artist the Duke brought to England. The Duke also added Worcester Lodge at the edge of the Park: a unique building with an elevated dining room over a grand archway, under a domed painted ceiling.

In time, Badminton House became synonymous with horse racing and fox hunting, but also gave its name to the sport badminton. The game was supposedly invented by the Beaufort children in a particularly harsh winter in the 1860s, when they found they could play indoors with a soft shuttlecock that would not damage the walls or the priceless Classical sculptures in the main entrance hall. Or was it a game imported from India, and only made popular in England? In other sports, the Badminton Horse Trials have been held on the estate since 1949, and the Beaufort Hunt is still one of the two most prominent in the United Kingdom. In terms of the house itself, although Badminton House is one of those rare great country houses that remains completely private and not open to the public, we can see many of its interiors in television series filmed there, most recently Bridgerton.

Aside from the contributions to the build-up of Badminton House in the 1740s, the 4th Duke also added an interesting title to the family’s collections, though his marriage to Elizabeth Berkeley, sister of Norborne, Baron Botetourt. Their son, Henry, 5th Duke of Beaufort, inherited the barony of Botetourt a few months before his death in 1803. Baron Botetourt was one of the last colonial governors of Virginia, and though his time in office was short (1768-70), his legacy was great. A new county in the western part of the colony was named for him in 1770, as was an endowed award at the College of William & Mary in Williamsburg, the colonial capital where he died and was buried in the crypt of Wren Chapel. A statue of Lord Botetourt has stood in front of the Wren Building since then (off and on), and is a much-revered symbol of the College. Years later, the small ensemble of the William & Mary Choir was named the Botetourt Chamber Singers, and when the Choir travelled to Europe in May-June 1993 (as written about by me in a previous blog post), we visited Badminton to commemorate this Botetourt link and were privileged to have a private tour conducted by the 11th Duchess of Beaufort herself. By this point, however, the title ‘Baron Botetourt’ was in fact in abeyance, since the 10th Duke had no children. The title had originally been created in 1305 for the Botetourt family, and passed to a cadet of the powerful Berkeley family of Gloucestershire by marriage in the 1350s, but was in abeyance from 1406. Norborne Berkeley, an MP for South Gloucestershire, in royal favour as a Groom of the Bedchamber to George III, was able to pull the barony out of abeyance for himself in 1764, but when he died in 1770 with no children, it went into abeyance again.

Lord Botetourt left not just the claims to this ancient barony to the Beauforts, but a beautiful house, Stoke Park. The Berkeleys had been lords of the manor of Stoke Gifford, a village to the north of the city of Bristol, since the 1330s. Sir Richard Berkeley had built a house upon a hill here in the 1550s, and this was significantly rebuilt by Norborne Berkeley in 1760. It became the dower house for successive generations of the Beaufort family until it was converted into a hospital for the mentally handicapped in 1909. The hospital was closed in the 1980s and sold for development—but was used for teaching rooms by the University of the West of England until 2003. Since then it has been converted into flats, but the estate of Stoke Park remains an extremely popular public park run by the city of Bristol.

The 5th Duke of Beaufort was only twelve when he succeeded. As he came of age in the 1770s he took on the family’s traditional roles in the Welsh borders, as Lord Lieutenant of Monmouthshire, then of Brecknockshire, deeper into Wales. He was also colonel of the Monmouth and Brecon militia. At court he was Master of the Horse to Queen Charlotte. After his death in 1803, his roles in Wales were taken over by his eldest son, Henry Charles, 6th Duke, who added a third lord lieutenancy, of Gloucestershire, in 1810. He was also Warden of the Forest of Dean. Henry Charles had previously served as a Tory MP (1788-1803), but stayed away from politics once he became a peer.

His younger brothers and nephews were more active in military and colonial affairs: his brother Lord Charles was Governor of Cape Colony, 1814-26, whose son became a Lieutenant-General in South Africa and Commander-in-Chief of the Bombay Army, 1855-60; his nephew Arthur was a Lieutenant-General and eventually Governor of Gibraltar, 1876-78; and his youngest brother, Lord Fitzroy (the 9th son of the 5th Duke!), was a Field Marshal and Commander of British troops in the Crimean War. Following an initial success at Alma, his reputation to posterity was memorialised after a terrible defeat at the Battle of Balaclava in October 1854 in the epic poem ‘The Charge of the Light Brigade’, by Tennyson. Lord Fitzroy, a soldier since the Napoleonic Wars—famously losing an arm at Waterloo—had been created Baron Raglan of Raglan in 1852; his aide-de-camp, Lord Calthorpe, interestingly, bore the unusual first name Somerset, as his mother was Lady Charlotte Somerset, Raglan’s younger sister. His health broken the failed attempts to take the city of Sebastopol, Lord Raglan died in Crimea in June 1855. He established a junior line of the Somerset family, with a seat at Cefntilla Court in Llandenny (in Monmouthshire). The family (and title) still exists, though they sold Cefntilla in 2015.

Both sons of the 6th Duke, Henry and Granville (named for his mother Charlotte Leveson-Gower’s family) were Tory MPs, the former in the 1810s-20s, the latter in the 1830s-40s (and he became a Privy Councillor and member of the Cabinet). The 7th Duke had married Lady Georgiana Fitzroy, another interesting link between two ‘illegitimate’ branches of the British royal family (he a Plantagenet, she a Stuart). They bought a house in London in 1840, on Arlington Street in St James’s Square, expanded it and renamed it Beaufort House. But though he spent lavishly on it, this house was not a family possession for long, sold to the Duke of Hamilton in 1852 a year before the Duke’s death.

The next duke (the 8th) was named Henry Charles, but was known as Charles; in the same way, all of his sons were named Henry, but went by their second names—names usually reflected a dynastic identity in the Middle Ages, and in the spirit of the 19th-century revived passion for all things medieval, this family revived its links with their medieval origins: the Henrician kings of the House of Lancaster. The 8th Duke was, as the family always was, a Tory, and served in the Earl of Derby’s government as Master of the Horse (1858-59 and again 1866-68). This office was by now mostly political, nothing to do with the sovereign’s horses. But he was heavily involved in sports: from 1885 he published the first of 28 volumes of books about sports known as the Badminton Library (the last appearing three years before his death, in 1896; though another five volumes appeared in the next two decades). He was still one of the greatest landowners in the UK, with over 50,000 acres in Monmouthshire and Gloucestershire, where, like his ancestors, he served as Lord Lieutenant for the Crown.

The eldest of his four ‘Henry’ sons (Henry Adelbert, Henry Richard, Henry Arthur and Henry Edward) was a fairly staid late Victorian and succeeded as the 9th Duke in 1899. His two brothers, however, made waves as prominent lords who scandalised society through their sexual behaviour. Lord Richard Somerset, Comptroller of the Royal Household in the 1870s, had to leave the country due to his love for a teenage boy. He lived in Florence until his death in 1932, and published poetry now identified with the school of late Victorian poets known as the ‘Uranians’. Lord Arthur, an equerry of the Prince of Wales, was involved in the even more high-profile ‘Cleveland Street Scandal’, 1889, in which several socially prominent men were identified as having encounters with male prostitutes—when questioned, Lord Arthur apparently pointed a finger at a much higher ranking figure, possibly the Prince of Wales’ son Prince Albert Victor (‘Prince Eddy’), so the investigation was rapidly hushed up. Somerset resigned his posts at court and in the army and also went abroad to avoid arrest, spending the rest of his life with a male companion in France (d. 1926).

The 9th Duke had a son, Henry Hugh, who became the 10th Duke of Beaufort in 1924. He was Master of the Horse for four sovereigns, between 1936 and 1978—the office had now ceased to be political and was now purely ceremonial, but certainly horse related. It was he who founded the Badminton Horse Trials in the 1940s, and was known for much his life simply as ‘Master’. The 10th Duke was, for good or ill, one of the world’s experts on foxes and fox hunting, as Master of the Beaufort Hunt. He was also President of the British Olympic Association from 1949 to 1966. Ceremonially, in addition to accompanying the sovereign at events like Trooping of the Colour, the Duke represented the Crown as Lord Lieutenant of Gloucestershire (from 1931), as well as the City of Bristol. His relationship with the royal family was always extremely close, not just due to shared love of the countryside, but due to his marriage in 1923 to Lady Mary Cambridge, the former Princess Mary of Teck, the niece of Queen Mary. Many stories are told of the Queen staying at Badminton during World War II and bringing with her truckloads of luggage (and reputedly ‘lifting’ certain Beaufort heirlooms to which she took a fancy).

When the 10th Duke died in 1984, Queen Elizabeth II attended his funeral. But he and Duchess Mary had no children. His sister’s grandson eventually inherited the Herbert barony in 2002, and in 2015 the Botetourt barony was split amongst her various descendants. But the dukedom, being a male only title, and the Badminton estate (entailed with the dukedom), passed to Mr David Somerset, already in his fifties, a great-grandson of the disgraced Lord Richard. He had been invited by his distant cousin to live at Badminton many years before, so the succession was smooth. As 11th Duke of Beaufort, he became President of the British Horse Society, and continued to lead the Beaufort Hunt which brought him into frequent conflict with hunt saboteurs. (there are some great photos of his life here: https://www.tatler.com/gallery/duke-of-beaufort-death-gallery). It was his wife, the former Lady Caroline Thynne (daughter of the Marquess of Bath) whom I met in the summer of 1993 (and wrote about here). I also had the pleasure of hosting their daughter, the historian Lady Anne Somerset, at a conference I organised in Oxford shortly after the publication of her celebrated biography of Queen Anne (published 2012).

Henry, 12th Duke of Beaufort, took over from his father in 2017. The estate is still enormous (about 52,000 acres). He is also known as singer-songwriter ‘Harry Beaufort’, and both his marriages reflect connections with the world of the arts: the first to actress Tracy Ward (granddaughter of the Earl of Dudley; sister of actress Rachel Ward; today an environmental campaigner as Tracy Worcester, her married name before her divorce), and the second to Georgia Powell daughter of a film director and granddaughter of a novelist. The Duke has a son, Henry, Marquess of Worcester, and a grandson, Henry, Earl of Glamorgan (b. 2021)—so despite the claims of the DNA ‘disjuncture’ the Plantagenets will still reign supreme for the next generations, at least in their horsey corner of Gloucestershire.

(images Wikimedia Commons)

4 thoughts on “Beaufort: the last of the Plantagenets”