In June 1790, Revolutionary France abolished the use of titles of nobility. While France was still a kingdom—for now—its Second Order no longer had a hereditary place at the top of society. Legally, there were no more dukes or princes in France. A decade later, in May 1804, First Consul Bonaparte was proclaimed Emperor of the French, and when he was crowned in Notre Dame in December, he needed a court composed of an entourage with noble honours. At first he created an imperial family, with the title ‘prince français’ for his brothers Joseph and Louis and his brother-in-law Joachim Murat, later extended to his other brothers Jérôme and (grudgingly, only at the very end) Lucien, plus his sister Elisa, his adopted son Eugène de Beauharnais, his adopted daughter Stéphanie de Beauharnais, and his uncle, Joseph Fesch. Also granted the rank of prince were those who held one of the Grand Dignities of State: two Arch-Chancellors (Empire and State), an Arch-Treasurer, a Grand Elector, a Grand Constable, a Grand Admiral and a Grand Huntsman. A year later an eighth, the Grand Almoner, was added, and by 1810 there were twelve. In keeping with the still pseudo-meritocratic ideals of the First Empire, these were essentially nobles of service, ie they weren’t inherently noble people, they just filled a specific function at court.

Emperor Napoléon realised that soldiers like rewards after winning victories, and the Order of the Legion of Honour was not sufficient for those of highest rank. Bonaparte’s best generals and closest military comrades had already been elevated to the supreme rank of Marshal of the Empire alongside the creation of the imperial princes in 1804. There were fourteen in the first promotion (plus four older generals who were semi-retired). Under the Old Regime, a Marshal of France held an equivalent rank to a duke, so it seemed logical to grant dukedoms to the most successful marshals. But France had abolished titles and fiefs, so at first, the Emperor looked abroad, to new territories being conquered abroad. So in 1806, principalities—sovereign but in vassalage to the Empire of the French—were given to Talleyrand (Minister of Foreign Affairs and Grand Chamberlain), Marshal Bernadotte and Marshal Berthier. These were, respectively, Benevento and Pontecorvo in Italy (both former papal enclaves in the Kingdom of Naples), and Neuchâtel in Switzerland (a former possession of the kings of Prussia). Soon after, in Spring 1807, he began to offer a different kind of title, a ‘victory title’ for those who had won a significant battle (like Danzig, below).

In 1808, the Emperor took another step forward and created a full new hereditary nobility, from princes down to barons, with complete and detailed regulations for heraldry, styles of address, and sums of money required to pass along titles to heirs (for example, 200,000 francs annual income was needed to secure a dukedom). But still, there was reluctance to have these titles reflect French placenames (in fact, Napoleon repeatedly denied a title to Marshal Jourdan, since he wished to be honoured for his victory at Fleurus, 1794—very early in the Revolutionary Wars—which was at that time part of France, though today it is in Belgian Hainaut). So most of these names were drawn from Napoleon’s other kingdom, the Kingdom of Italy, created in March 1805 (or in other subject territories like the kingdoms of Etruria or Naples). Altogether, between 1808 and 1815, there would be four victory princes, ten victory dukes, and twenty ‘duchies-grand fiefs’ (plus those principalities already named above, and three other dukedoms that were ‘anomalous’, including one for the Emperor’s former wife—see Beauharnais-Navarre). Only the ‘grand fiefs’ were attached to specific lands and incomes granted with the title. Of all these Napoleonic dukes and princes, some achieved a sufficient income and passed along their titles to sons, in varying degrees of recognition by the Bourbon royal governments after 1815 (or revived for cousins or other heirs by the restored Bonaparte regime of the Second Empire). Today there is still one principality (Essling), three victory dukedoms (Auerstaedt, Montebello and Albufera), and three regular dukedoms (Feltre, Otrante, Reggio). Most of these will eventually have separate blog posts; this post will focus exclusively on those titles that were awarded then vanished after only one holder (or in some cases two)—some lasting a few years, and in one at least, only a few days.

What is so interesting, to me, about all of these titles, is how they drew on men from all walks of life, and an equally interesting cross-section of women, from highborn ladies to washer women. The most famous names of the First French Empire, Ney, Berthier, Davout, Junot, Suchet, and so on, left families that carried on their ducal titles into the 19th and 20th centuries. What follows here instead are some of the lesser-known stories of the Napoleonic era, that burned bright and then were extinguished.

We can start with a Corsican, with someone who grew up with Bonaparte himself. Giovan Tomaso Arrighi de Casanova, 1st Duc de Padoue, born in 1778 (so nine years younger than the future emperor), was the Emperor’s cousin via his mother, Letizia Ramolino Buonaparte. The family was noble, like the Bonapartes, with roots in the centre of the island going back to the Middle Ages. Their seat was in Corte, and Joseph Bonaparte was born here. Giovan Tomaso’s father Giacinto was himself a prominent administrator in the revolutionary government—he had been a judge in the Superior Council of Corsica in the 1770s, then representative of the noble estates of Corsica at the court of Versailles in the 1780s. After the Revolution he became an administrator of the northern part of the island, and eventually Prefect of Corsica in 1811. By this point his younger two sons, Antonio and Ambrogio, had been killed in the wars, and his eldest had become a full general, having started his career in the entourage of his cousin Joseph Bonaparte, then served as aide-de-camp of General Berthier in Egypt. Here he earned his reputation as a commander, and he would eventually add a sphinx to his coat of arms. In 1808 he was created duke of Padua (Padoue in French), one of the cities in the Veneto (Venice’s mainland) that had been added to Napoleon’s Kingdom of Italy in 1806. In 1809 the Duc de Padoue was named an inspector-general of the cavalry. During the Hundred Days—when Napoleon returned briefly to power in Spring 1815—he was named Governor of Corsica, and a peer of France, but when the Bourbons were restored for a second time in July, General Arrighi de Casanova was put on the proscribed list and exiled. He lived in Lombardy until 1830s, and even after returning to France he kept a low profile, as a militant Bonapartist, until the tide turned in 1848, and he was elected to the National Assembly. In 1850 he was named Governor of the Invalides, and in 1852, his cousin Napoleon III named him a senator of the Second Empire. He died a year later, at Courson, a château he had acquired southwest of Paris, on the road towards Chartres.

The Duc de Padoue had married a woman from the higher aristocracy, Anne-Rose de Montesquiou-Fezensac, from one of the most ancient houses of southwestern France, and they had a son and a daughter. Ernest-Louis, 2nd Duc de Padoue, born the year of the collapse of the First Empire, saw great prominence in the Second. He was named a senator following his father’s death (and his ducal title was confirmed), and a councillor of state. In 1859 he was named Minister of the Interior and a Secretary of State. After the fall of the Second Empire, he returned to his family’s roots, and represented Corsica in the National Assembly, from 1876-81. When the 2nd Duke died in 1888, the title was extinct. His daughter Marie-Adèle could take the family’s wealth to her marriage to the Belgian aristocrat, the Duc de Caraman, but not the title. A cadet branch does remain, and are still prominent in Corsica.

After the Emperor’s cousin, we can turn to one of his closest confidants, who also became part of the family (distantly), by marriage. René Savary, Duke of Rovigo, played a crucial role in the imperial government as Minister of Police from 1810 to 1814. Son of a brewer from Charleville (on France’s northeast frontier) who had become commander of the nearby fortress of Sedan, René was the youngest of three sons. The elder two lost their lives in French military service, but by then, René had already risen much higher: by 1800 he was General Bonaparte’s preferred aide-de-camp and confidant, leading to his appointment in 1801 as commander of the elite gendarmerie assigned to defend the First Consul personally. The next year Savary married Félicité de Faudoas de Saint-Sulpice, a distant cousin and close friend of Hortense de Beauharnais, Bonaparte’s adopted daughter. They were then both promoted into the top ranks of the imperial hierarchy, he as brigadier general in 1803, and she as lady-in-waiting to the Empress in 1804. He continued to act as preferred aide-de-camp to the Emperor in the glorious campaigns of the next few years. He commanded his own troops at the battle of Ostrolenka in 1807 where he defeated a Russian army. The next year, he was rewarded with a dukedom, based on the small town of Rovigo on the River Po.

The new Duke of Rovigo had some diplomatic missions in 1807 and 1808 (to Russia, to Spain), but this proved not to be his forte. Instead, he was given more to do in the area of intelligence and spies (which he had been involved with for several years already), and replaced the disgraced Fouché as Minister of Police in 1810. He set about cracking down on freedom of the press, but missed signs for a pending coup attempt against the Emperor in 1812, so lost credibility with Napoleon and with the people. He kept his post, however, and was named by the Emperor to the Regency Council in Spring of 1814, to assist Empress Marie-Louise in ruling on behalf of her son Napoleon II. He and his wife accompanied her when she relocated to Blois at the time of the surrender of Paris.

The Duke of Rovigo did not rally to the Bourbons in the First Restoration, and resumed his duties as head of the Gendarmerie under the Hundred Days (though not as Minister of the Police, since Fouché returned to favour). Unlike most of the other dukes created by Napoleon, Rovigo loyally accompanied his master after his second abdication in July 1815, first to Rochefort to catch the ship to England, and then, he hoped, on to Saint Helena—but the British did not allow this. He was not welcomed back in France (where he was condemned to death by the Chamber of Peers), so was taken to a prison in British-held Malta. He was permitted to escape, travelled to the Ottoman Empire but was expelled by the Turks, travelled to Trieste and was arrested by the Austrians. He was also to return to France in 1819 for a second trial, and was acquitted and restored to his former honours. But he was never forgiven by royalists for some of his more shady involvements with espionage, in particular the capture and execution without trial of the King’s cousin the Duke of Enghien. In 1823, Rovigo published a memoir giving his version of these events of 1804; he accused others who were by then in favour with the King, so he was barred from court and once again went abroad. He lived in Rome until the July Revolution, and was then briefly restored to favour, being appointed commander of French troops in Algeria. Like many colonial officials of the era, he had a vision for new westernised extensions of Europe, and built a settlement called Rovigo with schools and hospitals etc, but his brutal repression of the local people left a bad legacy in French North Africa. He soon became ill, returned to France, and died in 1833.

The Duchess of Rovigo lived for another eight years. She and her husband had raised two sons and five daughters. The younger son, Tristan, became a Captain of Spahis in Morocco where he was killed in 1844. The older son, another René Savary, became 2nd Duke of Rovigo, and was a presence in French military and political affairs for the next three decades, but never rose to great prominence—unlike his father he was a strong legitimist, not a Bonapartist. He married twice, once to a woman from County Clare in Ireland, and the second time to the daughter of a surgeon in Geneva. He had a daughter from each marriage, but no son, so when he died in 1875, the duchy of Rovigo became extinct.

Another close companion of Bonaparte (and with an even shorter lifespan for his dukedom—five days—if it was even formally recognised by anyone at all), was the Duke of Ligny, created for General Girard in the days after the defeat at Waterloo. Jean-Baptiste Girard was the son of a merchant-tanner from Provence. At 19 he joined the Army of Italy and took part in Bonaparte’s early smashing successes in Italy then Egypt. By 1799 he was an adjutant-general, then in 1806 promoted to brigadier general. He commanded in the various campaigns in Spain, Russia and Germany, and was taken prisoner at Liegnitz in Silesia in August 1813, and held until the fall of the French Empire the next spring. He immediately rallied to the call of the Emperor in the Hundred Days and was an important element in the French victory over the Prussians at Ligny, 16 June, but he was mortally wounded. Napoleon was defeated at Waterloo on the 18th, yet he named the dying Girard Duke of Ligny on the 21st, and he died five days later. He had married an Italian woman while on campaign in 1799, and there were daughters, but no sons to potentially claim this most ephemeral of dukedoms.

Two other dukedoms held only by a single man were Gaëta and Decrès—neither of these were created for marshals but for members of the administration. The former at least follows the pattern of taking its name from a place in Italy, whereas the second was an anomaly and was simply the surname of its bearer.

Denis Decrès was from a minor noble family in the south of France (de Crès), who had begun his career in the royal navy in the 1780s, mostly in the West Indies. He maintained his naval service under the new regime and by 1798 was a junior admiral, commanding in the eastern Mediterranean, notably at Aboukir. From 1800 he shifted more towards a political career, and was named Maritime Prefect of Lorient, one of the chief naval bases in Brittany, then in 1801 was named Minister of the Navy and the Colonies. He maintained this post for the next thirteen years, despite rising criticism over the Navy’s declining reputation, the failed invasion of Britain in 1802, and the terrible defeat at Trafalgar in 1805. Much more enduringly, he has been criticised for overseeing the re-enslavement of Africans in the colony of Saint-Domingue (Haïti) who had been freed earlier in the revolutionary period. He was promoted to Vice-Admiral in 1804, Count of the Empire in 1808, then Duc Decrès in 1813.

This last promotion may have been due to his joining the extended network of families connected by marriage to the Emperor himself, via his marriage (also in 1813) to Marie-Rose (‘Rosine’) Anthoine de Saint-Joseph, a niece of Julie and Désirée Clary, the wives of Joseph Bonaparte and Marshal Bernadotte respectively (and her sister married Marshal Suchet, Duke of Albufera). Duc Decrès was re-appointed to his ministerial post in the Hundred Days, then retired from public life after Waterloo. He died in his Paris residence in 1820 in a fire set by servants who were trying to rob him. He had no children.

One of the witnesses of the wedding of Denis Decrès in 1813 was Martin Gaudin, Duc de Gaëte and Minister of Finance. Like his colleague, he held this post continually from 1799 to the fall of the Empire in 1814, and again during the Hundred Days in 1815 (in contrast to other ministers who came and went). The son of a lawyer in the Parlement of Paris, Gaudin had worked in the royal finance and tax administrations in the 1770s-80s. He joined the revolutionary movement in 1789 and was an influential member of the Finance Committee of the Constitutional Assembly that was set up to reorganise the Kingdom. Through the 1790s Gaudin was denounced several times for having royalist leanings, and miraculously survived each time. He earned the favour of First Consul Bonaparte who named him to his post as Minister of Finance the day after his Coup of Brumaire (November 1799). In 1804 he was named Grand Officer of the Legion of Honour, and in 1808 Count of the Empire, then in 1809, Duc de Gaëte, which took its name from the important city in the Kingdom of Naples, Gaeta. Like Decrès he also retired from public life after 1815, but did return to play an important financial role once more in 1820 when he became Governor of the Bank of France, a position he held for fourteen years. He also married, quite late, in 1822, Marie-Anne Summaripa, an aristocrat from the Greek island of Naxos who had been married to a French diplomat in Constantinople. They had no children, so when he died in 1841 the title became extinct. It’s worth noting that there was another Duke of Gaeta created in the 19th century, created in 1870 for Enrico Cialdini, one of the revolutionary soldiers in the Italian Risorgimento. His ducal title also died with him, in 1892.

Unlike the dukes of Padoue, Rovigo or Ligny, young men who rose to prominence alongside General Bonaparte, another one-off duke was an older man, who like Decrès and Gaëte, already had an established career before the Revolution. Marshal Lefebvre, Duke of Danzig, born in 1755, became one of the closest military companions of the younger General Bonaparte. His is an inspiring rags-to-riches tale, popularly retold in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, notably with his wife as the protagonist, a washerwoman from Alsace who rose to be a senior courtier in Paris. François-Joseph Lefebvre was the son of a local military official in a small town in Alsace, who had joined the Royal Guard when he was 18 back in 1773. In 1783, he married Catherine Hübscher, a local washerwoman and barmaid, and together they moved to Paris as he rose through the ranks of the Royal Guard. When the Revolution broke out, Lefebvre at first remained loyal to the Old Regime, defending the royal family at Versailles during the attacks of the autumn of 1789, and even assisting the King’s aged aunts, Adélaïde and Victoire, in their escape from France in Spring 1791.

As the popular story goes, it was soon after, in the summer of 1792, when Catherine Lefebvre took pity on a penniless and friendless Corsican captain, Napoleone Buonaparte, and took care of washing his clothes to help him maintain appearances. How much of this is true and how much is legend will probably never be known. Once the Republic was proclaimed in September 1792, her husband’s star rose swiftly, as a brigadier general from 1793, and division general in 1794, leading troops in actions against Allied armies in the Rhineland. Captain Buonaparte, meanwhile, made his name in late 1793 masterminding the siege of Toulon. In 1799 their fortunes came back together in Paris, and General Lefebvre, who had been named military governor of Paris in March, was a key supporter of General Bonaparte in the Coup of Brumaire in November. Now as First Consul of France, Bonaparte secured the election of his friend as a Senator of the Republic in 1800, then promoted him as Marshal of the Empire in the first round of promotions of 1804.

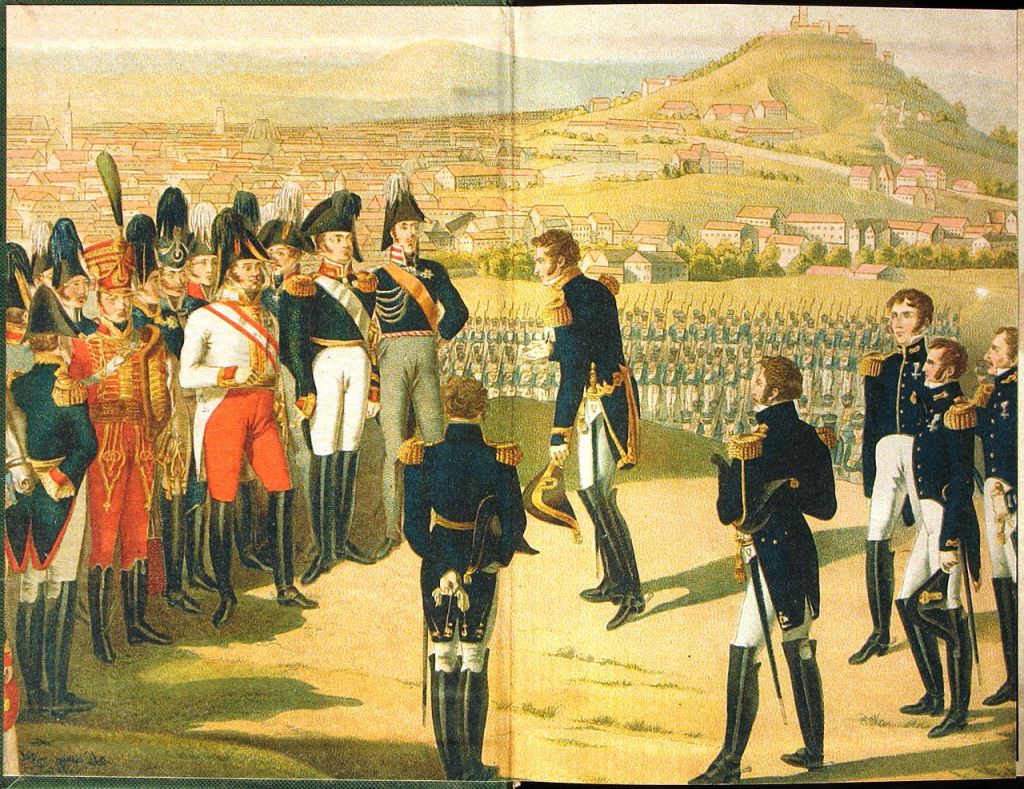

Marshal Lefebvre continued to hold important commands in Germany, and was named Commander of the Imperial Guard, infantry, in 1806. He led this elite unit at Jena in October 1806, then successfully besieged the important Prussian port city of Danzig in March to May 1807. For this he was rewarded in May 1807 with the ‘victory title’ Duke of Danzig (spelled ‘Dantzig’ in French; today’s city of Gdańsk in Polish), and a large sum of cash presented by a grateful emperor in a chocolate box when they met at the nearby abbey of Oliwa. In the following years the Marshal-Duke was sent on commands in Spain, then back to Germany, and led the Old Guard in the Russia campaign of 1812—during which he lost his eldest son, who himself had risen through the ranks, first as his father’s aide-de-camp, then as brigadier general in his own right. One son remained, of an extraordinary thirteen altogether, but he too died a few years later in 1817, still a teenager.

By this point, the new Duchess of Danzig was having to hold her own at court in Paris. The Emperor and his snobbish sisters were apparently repulsed by her coarse manners and language, which she refused to ‘amend’, earning her later the nickname ‘Madame Sans-Gêne’ (‘without embarrassment’) in later plays and films about her life. But as the story goes, the Emperor never forgot their original connection and never sent her away from his court in the Tuileries.

The Duc de Dantzig remained loyal to the Emperor to the very end in 1814, unlike some of the other marshals, but swiftly acknowledged the restoration of King Louis XVIII and was named a peer of France. He did rejoin Napoleon in the Hundred Days, however, so was excluded from the Chamber of Peers in the second restoration of 1815. His peerage was restored in 1819 but he died a year later. His wife retired to the chateau of Pontault-Combault in Brie (east of Paris), which she and her husband had purchased in 1813 (today it is the Hôtel de Ville of that small town). Here she stayed true to her roots and supported the poor by means of various charities with her now very large fortune. She died in 1835. With no sons to succeed, the dukedom of Danzig was extinct.

Another of the Emperor’s most loyal courtiers—in fact nicknamed ‘l’ombre de Napoléon’ (‘Napoleon’s shadow’), Duroc, was given a dukedom, but was not a marshal of the Empire. He was amongst the small group of imperial dukes whose titles were granted due to their high positions either politically in the government, or ceremonially and administratively in the imperial court. Duroc was in the latter category as Grand Marshal of the Palace from 1805. As such he was the head of the military household and in charge of palace security, especially at the Tuileries where he acted as governor.

Géraud-Christophe Duroc (or Du Roc) was the son of Claude de Michel du Roc, the younger son in a robe noble family from the south of France who had moved north to Lorraine and became captain in a regiment of dragoons. Claude married late at 48 and finally had a son at 52, and lived to be almost 90, dying in 1809, having added the surname Michel to his forenames, to sound less noble. The son, Géraud-Christophe, born in 1772, came of age at the start of the Revolution, and at first left France as a noble émigré, but after the first major victory of the revolutionary armies at Valmy in 1792, he returned and joined their cause. His friendship with Napoleon started when he served as his aide-de-camp in the Italian campaigns of 1796 and then in Egypt. He was promoted to the rank of brigadier general in 1800, but was also sent abroad by the now First Consul Bonaparte on diplomatic missions. From 1805 he was governor of the Tuileries and Grand Marshal of the Palace, and in 1808 was created Duc de Frioul, which took its name from the region of Friuli in northeast Italy. He continued to accompany the Emperor on most campaigns and was killed at the Battle of Bautzen in Saxony in May 1813. Napoleon wrote later that he felt closest to Duroc, and demonstrated this in an intimate manner by taking the name Duroc as an incognito when he travelled to Rochefort after his abdication in early July 1815 (and reputedly proposed to use the name ‘Colonel Duroc’ if he had been granted exile in Britain, which of course he wasn’t).

Duroc had married in 1802 Marie-des-Neiges Martínez de Hervas, whose father managed a Spanish bank in Paris, and who would later serve as finance minister for Joseph Bonaparte when he was named king of Spain. In 1813, she was given the duchy of Frioul to support herself as a widow, which, as a ‘duché-grand fief’ included lands and revenues granted by the Emperor. She remarried in 1832, another general, Charles Fabvier, and lived—like her father-in-law—to be almost 90. There had been one son, Napoléon-Louis Duroc, who lived for a year (1811-1812), and a daughter, Hortense-Eugénie, who, had she outlived her mother (she died in 1829, aged 17), might have been able to call herself ‘2nd Duchesse de Frioul’, but this is uncertain and would have depended on the goodwill of King Louis XVIII.

A Napoleonic duke who did gain the goodwill of the restored Bourbon king, perhaps too swiftly, was Marshal Augereau, Duc de Castiglione. In contrast to Dantzig or Duroc, this member of the one-off dukes club was never a close friend of Bonaparte, and ended up in disgrace for having abandoned him so quickly in favour of the Bourbon Restoration. Born in 1757 in one of the poorest neighbourhoods of Paris, the faubourg Saint-Marcel, the son of a domestic servant and a fruit seller, Charles-Pierre Augereau, launched a military career as a young man in the French army, but was forced to flee abroad after drawing his sword on an officer. Much of the facts about his subsequent meanderings across Europe are open to question as we only have his own testimony, and he seems to have been prone to exaggeration. He served for some periods in the Prussian army, then in the armies of Naples and Portugal, but also spent time as a fencing master or even a brigand, before returning to France in 1792, inspired by the revolutionary events there. Within a year he was a general, first in the Army of the Pyrenees and then the Army of Italy, where, in August 1796, he led his troops to victory over the Austrians at Castiglione—hence the later name of his ‘victory title’.

Back in France, General Augereau got involved in politics, supporting the far left, and as elected Deputy representing the Haute-Garonne (the department surrounding the city of Toulouse). But he hesitated in supporting the coup led by his fellow general, Napoleon Bonaparte, in November 1799 (18 Brumaire), then accepted a posting to lead French troops sent north to spread the revolution to the Batavian Republic (the new name for the Dutch Republic). He continued to fall in and out of favour with now First Consul Bonaparte, but was too good of a commander to be dismissed. So he was included in the first promotions to the rank of Marshal of the Empire, in 1804, and held various commands in the campaigns in Germany, Spain and Russia. In 1808 he was given his dukedom of Castiglione, a small town in the Veneto near Lake Garda. He also remarried, a woman of much higher social class. His first wife, Gabriella Grach, had been born in Smyrna (the Greek city now called Izmir), the daughter of a rich merchant (or so he claimed), and eloped with young Augereau while he was serving in Naples. She died in 1806, and the Marshal re-married Adélaïde-Joséphine de Bourlon de Chavange, who was only 19! In 1812, the new Duchess of Castiglione was appointed one of the ladies-in-waiting of the Empress Marie-Louise, thus helping the Duke solidify his ties to Napoleon’s court.

But it wasn’t enough, and he defied the Emperor’s orders to keep Lyon loyal in the Spring of 1814, when everything was falling apart; not wishing the destroy the city, he did not pursue the siege. Napoleon criticised him publicly, and in mid-April, Augereau formally denounced the Emperor and declared his loyalty to the restoration of the Bourbons. Louis XVIII made him a peer of France and a knight of Saint-Louis. In the Hundred Days of 1815, however, Augereau expressed willingness to join the Emperor once more, but this time Napoleon rebuffed him and denounced him as a traitor. After the second restoration of the monarchy, the Duke of Castiglione took up his seat in the Chamber of Peers, but died soon after, in 1816, at his Château of La Houssaye in Brie. His wife re-married, a Belgian nobleman, the Count of Sainte-Aldegonde, and returned to active court service herself as an older woman, as a lady-in-waiting to Queen Marie-Amélie from 1831. Marshal Augereau had no children to carry on his ducal title; he had a half-brother, Jean-Pierre, who was also a general, and a baron of the Empire (1811), but he did not inherit the ducal title, and himself had no children.

An even worse betrayer of Napoleon was Marshal Marmont. Auguste-Frédéric Viesse de Marmont, Duc de Raguse, had come to prominence with Bonaparte when they both served in the artillery at the siege of Toulon in 1793. He became a very successful general of the Republic and marshal of the Empire but became too independent after he was given his own territories to govern in 1811; his sudden alliance with the Bourbons in April 1814 blackened his name for a century in the memory of the French people. Indeed the verb ‘raguser’ was used to mean a base betrayal until the end of the nineteenth century. Nevertheless, he had one of the longest and most interesting careers of any of the Napoleonic dukes.

Unlike several of the other marshal-dukes listed here, Marmont was not a rags to riches story. He was from a noble background. His grandfather Edme Viesse had been a prominent administrative official in northern Burgundy and acquired the fief of Marmont, as well as the office of royal secretary in the Parlement of Besançon which was an ennobling office. His father Nicolas Edme built on this by entering military service (a typical pathway to transform an administrative family into a noble one) but also increasing the family wealth by operating large iron forges on their estates in northern Burgundy. He acquired the fifteenth-century château of Châtillon-sur-Seine, which was renamed Château Marmont.

Auguste-Frédéric was born in 1774. He rose through the ranks alongside Bonaparte and was named a Brigadier General in 1798 (as a reward for his successful capture of Malta from the British, which enabled the French armies to return safely from the Egypt campaign). Following the Coup of Brumaire (1799), First Consul Bonaparte named him a Councillor of State, and promoted him to Division General after his victory at Marengo over the Austrians. In 1804, he was named General-in-Chief of the Army of Holland, sent to restore order in the French satellite ‘Batavian Republic’. While he was there he erected a curious monument, a great pyramid near Utrecht, and a new town he called ‘Marmontville’. But he was not amongst the first round of promotions as Marshal of the Empire, which irked him—the beginnings perhaps of the breakdown of his relationship with Napoleon. He was also disappointed in 1805 when his plans to invade Britain from Holland failed to come together.

In 1806, General Marmont was transferred to another sphere of the expanding French Empire, as Governor of Dalmatia, the former Venetian province along the eastern shores of the Adriatic Sea which he secured for Napoleon’s new Kingdom of Italy, and to which he added the Republic of Ragusa (today’s Dubrovnik), ending its 450 years of independence. His title, Duke of Ragusa (or Raguse in French), granted in 1808, was thus one of the ‘grand fiefs’ that was actually quite closely tied to his interests and fortunes (the duchy came with a large annual income of 50,000 francs taken from lands in Dalmatia). Here too he saw some disappointments in the direction of Napoleon’s foreign policies, as he hoped to use his base in the Balkans to launch an invasion of the Ottoman Empire and spread the French Revolution and its values to the peoples of the Near East (much as Napoleon himself had desired to do a decade before in Egypt and Syria), but this was not supported. Another important victory over the Austrians at Znaim in Bohemia, 1809, finally earned him his marshal’s baton, and a promotion to the post of Governor-General of the Illyrian Provinces. This territory, separated from the Kingdom of Italy in 1809, included Dalmatia and Ragusa, but also now included the former Austrian provinces of Carinthia and Carniola. The latter, today’s Slovenia, became the centre of French administration, with its capital at Laibach (now Ljubljana). The Duc de Raguse became virtually an independent ruler here as the French Emperor turned his attentions elsewhere. Some suspected that Raguse had visions of becoming a king in Illyria, having seen the successes of marshals Murat in Naples and Bernadotte in Sweden, and, perhaps to derail these ambitions, he was soon redeployed by Napoleon elsewhere in Europe, first as commander of a French army in Northern Spain in 1811. He was seriously wounded in battle and retired back to France.

Returning to the army in Spring 1813, the Duc de Raguse participated in the major battles of the Germany campaign, and after the French armies were pushed back across the Rhine into France itself at the end of the year, he continued to defend the capital as the Allies advanced little by little towards Paris in the Spring of 1814. At one point in early March he was sharply criticised by Napoleon for executing a strategic retreat, sneering that ‘he had conducted himself like a sub-lieutenant.’ Nevertheless, he continued to fight in the districts east of Paris, and by the end of the month was left in charge of defending Paris. In the face of a much larger Allied force, he signed an armistice on 31 March that allowed the French army to withdraw from the city. This agreement was signed at 2 AM with Russian commanders at the Hôtel de Marmont (also known as the Hôtel de Raguse). This was a large house in the northern edge of the city (near today’s Gare du Nord) built in the 1770s which he had acquired as part of the dowry of his wife Anne-Marie Perregaux, daughter of the rich banker, Jean-Frédéric Perregaux (as this neighbourhood declined, the house was mostly dismantled/refashioned in the 1930s).

The Emperor rejected calls for his abdication by the Allied Powers, so proposed a renewed assault on Paris. The Senate announced the end of his regime on 2 April, and sent out feelers to Marshal Marmont to see if he would carry on fighting or join them. On 5 April he negotiated directly with Austrian and Russian officials and agreed to join his army to theirs; this led to the abdication of Napoleon on the 6th and earned Marmont the lifelong hatred of diehard Bonapartists. Marshals Marmont and Ney went to Compiègne to receive Louis XVIII on 29 April and to formally welcome him back to France.

The restored Louis XVIII created the Duke of Ragusa a peer of France and named him major-general of the newly re-formed Royal Guard. The following Spring, during the Hundred Days, Ragusa did not support the return of the Emperor, but fled with the King to Ghent; nevertheless, in the Second Restoration, the King distrusted his loyalty and he was marginalised. He therefore focused his energies back in Burgundy, developing his family’s forge business at Châtillon. These business ventures were not successful, and he found himself strapped for cash, so he pressed the Austrian government to restore the pension from the estates of Dalmatia that had been created along with his duchy. Perhaps surprisingly, Austria had promised to do this according to the various settlements that ended the Napoleonic empire, so he did in fact receive this money. Nevertheless, it was not enough and he was forced to sell the Château de Marmont in 1826.

But the story of Marshal Marmont, Duke of Ragusa, was not finished. In 1826, the new King, Charles X, relied on the good relations Marmont had established with the Russians back in 1814 and sent him as France’s official representative at the funeral of Tsar Alexander. This renewed royal favour was once more even more strongly demonstrated at the very end of June 1830, when the King appointed him Military Governor of Paris, in an attempt to restore order in the political unrest which in the coming weeks developed into a full insurrection, later termed the ‘July Revolution’. When the King abdicated on 2 August, Marmont went with him, first into exile in Great Britain, and then to Austria, where he again (remarkably) ensured that his Dalmatian pension would still be paid, but turned down an offer of employment in the Austrian army. Curiously, here he spent time with the living remnant of Napoleon’s empire, his son, the Prince Imperial (or ‘Napoleon II’), now called the Duke of Reichstadt. In Vienna his use of the title Duke of Ragusa clashed with political realities, since the Emperor (Francis I) now added this title to his own, as the entire Illyrian coast had been restored to Habsburg rule. Nonetheless, his memoirs, published after his death, prominently used both titles, Marshal Marmont and Duc de Raguse. He settled in Venice in 1838 where he lived mostly forgotten until his death in 1852—the last marshal of the First Empire.

In the end, this survey reminds us that the link between military leadership and the ducal title—its original purpose—had not been forgotten by the age of Napoleon. Under the Old Regime in France gaining a marshalcy was often the penultimate step towards gaining your family a ducal title, the crowning achievement for any noble house. But like many of the marshals of France under the Old Regime, a life spent in the military often mean long periods of time away from home, and the marital bed, and thus the failure of a family to generate more than just a ‘one-off’ duke.

(images Wikimedia Commons)