Readers of this site will know by now that I am slightly obsessed with trans-national noble families that moved effortlessly across Europe in the 18th and 19th century, blissfully ignoring the boundaries of nationalism and attempting, in their way, to hold the continent together through kinship networks and cultural exchange. The recent new film Napoleon brought back into my mind the family of his lifelong love, Joséphine de Beauharnais, and the amazing, and very trans-national journey across Europe taken by her descendants—not his—in the century that followed. By the 1820s the Beauharnais were an adjunct part of the royal family of Bavaria, as dukes of Leuchtenberg. And by the 1840s they had been created Prince Romanovsky, again as sort of an additional dynastic branch, this time to the imperial family of Russia.

Joséphine de Beauharnais was the grand progenitrix of this pan-European clan, though she did not live to see it. And she herself was only a Beauharnais by marriage. She was however, created a duchess in her own right (the strangely named duchy of Navarre, see below), as a consolation prize for being divorced from the Emperor Napoleon, so she does qualify for a place on the ‘Dukes and Princes’ blogsite. Her daughter too, Hortense de Beauharnais, was given a duchy, Saint-Leu, this time by the restored Bourbon regime after the fall of Bonaparte. There were thus two dukedoms in France before the titles in Germany or Russia were granted to the Beauharnais family; so let’s start in France.

Marie-Josèphe-Rose Tascher de la Pagerie, known as Rose or Marie-Rose in the days before she met Napoleon Bonaparte (who preferred to call her Joséphine), was born on the island of Martinique in the Caribbean in 1763, to a wealthy owner of sugar plantations. Her father aspired to marry her up the social ladder, so in 1779 he arranged her marriage to the younger son of a former governor of their island, Alexandre, Vicomte de Beauharnais. The new couple started a life together in France, where he was serving in the army, and soon had two children, Eugène (1781) and Hortense (1783).

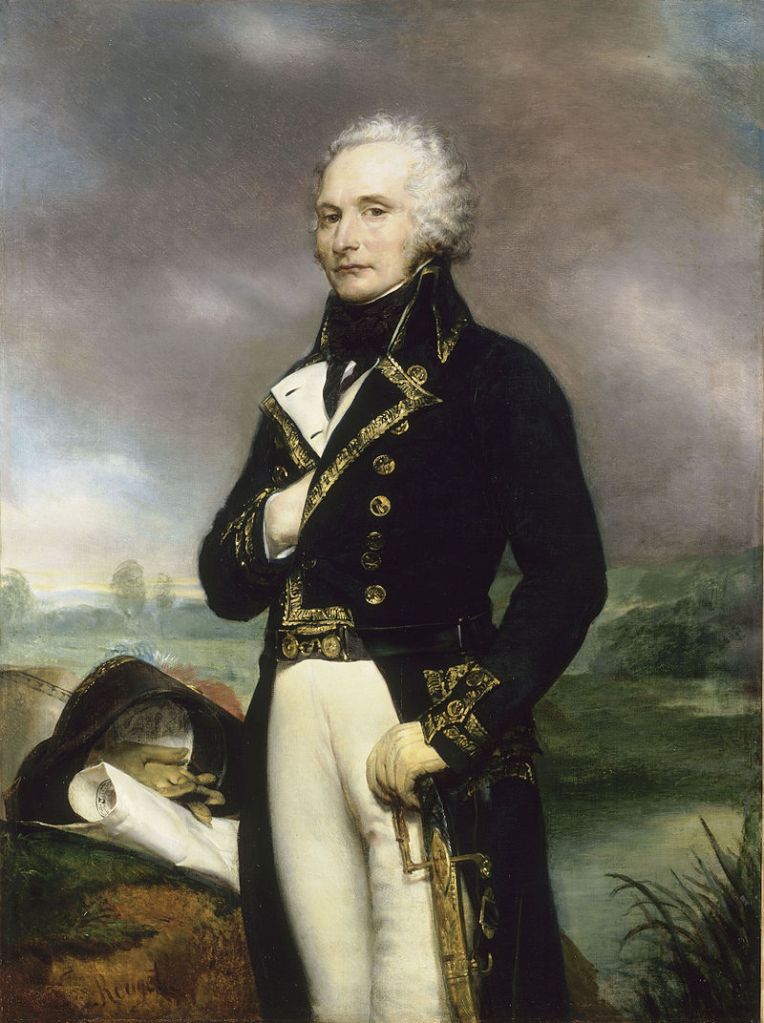

Alexandre’s family may have been socially superior on Martinique, but they were still relatively nouveau amongst the noble families of France, and he was not formally received at court, which irked him. His military career was also stunted somewhat since, by the time he arrived back in the Caribbean to help the French navy fight against the English in the American War of Independence, the war was over. Like many young noblemen, however, he did pick up dangerous new ideas about democracy percolating around in the New World at this time, and was an eager participant in the Estates General of 1789 as a delegate for the nobility of Blois. When the Revolution broke out that summer, Alexandre was one of the first nobles to join the Third Estate, and in the coming years he joined the Jacobin political club and sat twice as president of the National Constituent Assembly, in July/August 1791. A year later, Citizen Beauharnais re-joined the army, now as a general, and by 1793 was commanding the Army of the Rhine. Blamed for the loss of the city of Mainz, however, he resigned his commission and retreated to his family’s estates in the area south of the city of Orléans. But the long arm of the Terror reached him and in March 1794 he was arrested, blamed for the military failure in Germany and suspected of still harbouring subversive aristocratic tendencies… He was executed in Paris on 5 Thermidor of Year Two (ie, 23 July 1794). His wife Marie-Rose was also arrested, in April, and her life was spared only by the fall of the regime a mere five days after her husband’s death.

Alexandre’s ancestors, the Beauharnais family, were originally merchants in the city of Orléans—the first named is Guillaume, living in 1390, who was also lord of Miramion, an estate northeast of the city. His descendants expanded their landholdings with the lordships of La Chaussée (or La Chaussaye) and La Boëche, also near Orléans. By the end of the 16th century the family had become part of the noblesse de robe (the judiciary nobility), and held prominent provincial posts: François II (d. 1651) was First President in the Presidial Court of Orléans in 1598 and the King’s Lieutenant-General in the Bailliage of Orléans. He was selected to attend the Estates General of 1614. His son Jean raised the social profile of the family somewhat by acquiring a position at court, that of maître d’hôtel du roi in 1652, and in the next generation they secured their place in the capital as advocates in the Parlement of Paris. It was Jean’s grandsons, François and Charles, who really raised to the family closer to the top of the French aristocratic hierarchy, as prominent leaders of France’s new colony in the New World.

François de Beauharnais (b. 1665) became a protégé of a distant kinsman Jérôme Phélypeaux, Comte de Pontchartrain, who, as Minister of the Navy secured his appointment as Intendant of New France in 1702. The intendant was the civil administrator of the colony, second in command to the governor. François acquired land in Acadia (today’s New Brunswick) which was erected into a feudal estate (the barony of Beauville or Banville). After three years, he returned to France and was given the much more prestigious post of intendant of the Navy, then intendant of the district of La Rochelle until 1715, when he, as part of the Phélypeaux network, fell from royal favour. Meanwhile, his brother Charles had already been making a name for himself as a naval captain, and in 1716 married a rich widow, Renée Le Pays de Bourjolly, whose estates included sugar plantations in Saint-Domingue (today’s Haïti) in the Caribbean. By the mid-1720s, the Phélypeaux family were back in favour, and the new Minister of the Navy, the Comte de Maurepas, appointed Charles de Beauharnois (as it was often spelled then), Governor of New France (1726-46). His time as governor was spent trying to maintain the delicate balance between the British in Canada (in Ontario) and the various native regional alliances (the Abenaki, the Iroquois, the Sioux). This balance was disrupted by his brutal suppression of the Fox tribe (or Renards in French) in the region between lakes Superior and Michigan in the late 1720s. Governor Beauharnois solidified New France’s reach into this territory and much further west with a new fort (1727) on the upper reaches of the Mississippi: Fort Beauharnois (now in Minnesota). He also gave this name to his seigneurie, established in 1729 on the south side of the Saint Lawrence river, southwest of Montréal. The Seigneurie of Beauharnois was later sold when France lost control of Québec in the 1760s, but it remains today as a town and the seat of a county.

In 1744, the War of Austrian Succession spread to Canada, and Governor de Beauharnois tried to build up Quebec’s defences against a British attack. But at age 74, he was seen as too old to face this major challenge, and was soon recalled. Back in France he was named a lieutenant-general of the navy in retirement, and he died a few years later. Neither François nor Charles had any children, so their wealth and estates passed to their nephews, François and Claude-Joseph, the sons of their late younger brother Claude, who had himself been a naval captain in what was now a family tradition. The older brother, François, Baron de Beauville, likewise rose through the navy to become a squadron commander, and in 1757 was appointed Governor-General of the ‘Isles du Vent’, that is the Windward Islands in the Caribbean. This post covered all of the French possessions in the Antilles except the large island of Saint-Domingue, and was based in Martinique. He was the last to be called Governor-General—after 1763 each island was given its own governor. After his sons were born on the island, François returned to France where his newly acquired estate, La Ferté-Avrain in the Sologne region south of Orléans, was erected as a marquisate (1764) and renamed La Ferté-Beauharnais. The old medieval château here was mostly dismantled and a new house was built in a fashionable classical style. It would later be ruined during the Revolution and sold by the family in 1821.

The new Marquis’ younger brother, Claude-Joseph, was also raised in rank, as Count of Les Roches-Baritaud, an estate he had purchased in the Vendée, the western portion of Poitou, near the Atlantic coast north of La Rochelle. He too was a captain in the French navy, and won a significant victory over the British off Lizard Point (Cornwall) in 1756. He died before the French Revolution broke out, but his wife ‘Fanny de Beauharnais’ lived on for many years, and flourished as a salonnière, a well-known writer of poems, plays and novels. They had three children, who would re-appear prominently in the Napoleonic regime: Anne as wife of General de Barral, and Claude as a Senator and Count of the Empire (likely due to the intervention of his cousin-in-law, Empress Joséphine), then as Chevalier d’honneur to Joséphine’s replacement, Empress Marie-Louise, in 1810.

After 1794, Joséphine was a widow. Her late husband’s older brother, François, Marquis de la Ferté-Beauharnais, had remained an ardent royalist, in opposition to his own brother, then emigrated when things heated up in 1792. He joined the Army of Emigrés fighting against the new regime, and didn’t return to France until the amnesties of 1802—from abroad, he even tried to convince First Consul Bonaparte, via the Consul’s new wife (Joséphine), to use his position to restore the Bourbon monarchy. This suggestion fell on deaf ears of course, but in 1805 François was briefly given a chance to make his name in the new Empire, as ambassador to Tuscany, then to Spain. He failed to follow Napoleon’s orders in Spain, however, and was soon recalled and exiled to his estates. He died age 90 (!) in 1846.

So finally to Joséphine and her children by her first husband the Vicomte de Beauharnais. Without taking too much of a detour into the history of Napoleon Bonaparte, we can summarise the astonishing career of this minor nobleman from Corsica who became an artillery specialist and dazzled the leaders of the first French Republic in the 1790s, then led a coup to bring down those same leaders once it was clear their regime was corrupt and ineffective, revealed himself to be a genius military strategist and effective politician, then crowned himself Emperor of the French and founder of a new reigning dynasty for France in 1804. Along the way, he needed the social cachet provided to him by the widowed Vicomtesse de Beauharnais to gain entrée into Parisian high society, just as she needed him to remain relevant in a swiftly evolving political landscape. For the purposes of this blog about dynasty, it is her children who also brought value to her marriage to Napoleon, since, as any good Italian mama’s boy—and he was, as we see so well in the recent film, when his mother Letizia Ramolino took matters into her own hands to ensure her son’s ‘potency’—he was obsessed with creating a dynasty and ensuring his legacy. In the absence of a son of his own he tried to build up the profile of his brothers, to little effect—none but Lucien was really an effective leader, and they fell out over the idea of an imperial Bonaparte dynasty. And so Napoleon adopted Joséphine’s children, Eugène and Hortense, unofficially from the time of their marriage in 1796, and officially in 1806, shortly after the proclamation of the Empire.

Eugène de Beauharnais (b. 1781) began his apprenticeship to power in Italy as aide-de-camp to his new step-father in 1797, then the following year on campaigns in Egypt and Syria. When Napoleon was appointed First Consul, Eugène was named Captain of the Light Cavalry of the Consular Guard, 1800, and rose to the rank of general in 1804. That year the Empire was proclaimed, and Eugène was created a ‘Prince of France’, with the style of ‘Imperial Highness’, and soon after was appointed Arch-Chancellor of State, one of the seven ‘Grand Dignitaries of the Empire’ set up to demonstrate to Europe (and to other Frenchmen) that the Empire of the French had a magnificent court just like anyone else.

The new Arch-Chancellor had also recently acquired his own grand residence in Paris, in one of the choicest locations in the city: the old Hôtel de Torcy, built by Louis XIV’s foreign minister in 1714 on the banks of the Seine between the Palais Bourbon and what is today the Musée d’Orsay. Set back from the quays somewhat, it had a marvellous garden overlooking the river. Eugène purchased it in 1803, remodelled it in the now ultra-fashionable Egyptian neo-classical style, and renamed it the Hôtel de Beauharnais. After the fall of the Empire, it would be purchased by the King of Prussia, in 1818, and it would serve as the embassy of Prussia, then Germany, until 1944; since 1968 it has been the residence of the German ambassador.

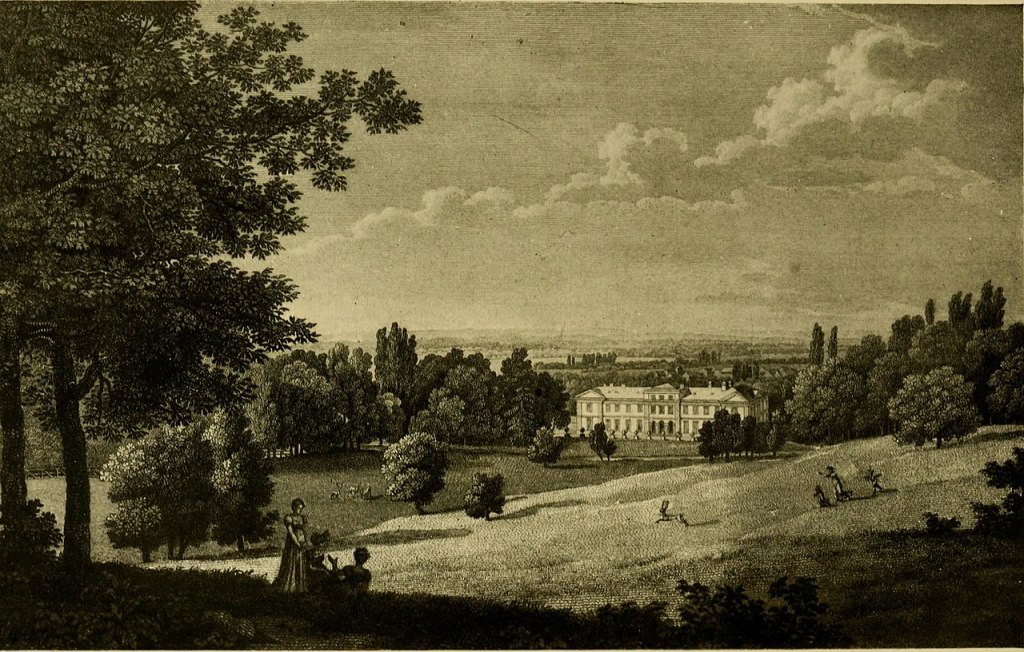

By this point, his mother Empress Joséphine also had a prominent residence of her own, the Château of Malmaison, purchased in 1799 and lovingly refurbished as the country seat of the First Consul then Emperor. Located on a bend of the river Seine about 7 miles west of Paris, Malmaison had been a dilapidated 17th-century country manor, and she transformed it into a palace, especially noted for its rose gardens. Since the early 20th century it has been property of the French state, and remains one of the best places to see the preserved ‘empire style’ of the era of the Empress Joséphine.

An even more significant appointment came to Joséphine’s son Prince Eugène the next year: Napoleon returned to Italy and resurrected the ancient Kingdom of Italy (essentially Lombardy, but soon to include the Veneto too), crowning himself with the ancient Iron Crown in Milan in May 1805; he then left the Kingdom in the hands of his step-son Eugène as Viceroy. Eugène turned out to be a very good politician and administrator, keeping the peace (for a time) with the Papacy, carrying out a number of public building projects, and implementing the new Civil Code to align with that of France. As part of the extended Imperial family, he was used in the Emperor’s matrimonial chess manoeuvres, and was married in January 1806 to Princess Augusta of Bavaria, to secure France’s alliance with that key German state, which, in return, was recognised as an independent kingdom that same month. It was also in this same month that Eugène was formally adopted by the Emperor, and though it was made clear he was not heir to the French Empire, he was named heir to the Kingdom of Italy, should Napoleon fail to have a son. As a sign of this, and the addition of the Veneto to the Kingdom of Italy, he was created Prince of Venice, December 1807. Earlier in the year, he had given the Emperor his first Beauharnais grandchild, named Joséphine after her grandmother, and she was created Princess of Bologna, and later given further estates in that region and created Duchess of Galliera. It seemed the destiny of the Beauharnais dynasty was to be in Italy—perhaps ironically given the origins of the Buonaparti. The Prince of Venice earned his spurs on the battlefield in Italy too, as Commander of the Army of Italy in the War of the Fifth Coalition (1809), successfully defending the newly acquired Veneto provinces against the Austrians at the Battle of the Piave in June.

Hortense de Beauharnais (b. 1783) was raised to be part of the wider Bonaparte family too. She’d been educated at school with Napoleon’s sister Caroline, and in 1802—before the proclamation of the Empire and the systematic efforts of the Emperor to marry his siblings into the reigning houses of Europe—she was persuaded to agree to a marriage with her step-father’s younger brother Luigi. As Louis I, King of Holland, from June 1806, her husband was then sent to bring the Dutch into line with Napoleon’s grand European family alliance, and Hortense was forced to go with him. She grew to like her little court in The Hague and became popular with the Dutch. But she hated Louis, and within a year she returned to France, officially to recover her health after the death of a baby son. She revelled in holding the rank of queen in Paris, young and spirited, second only to her mother at the Imperial court.

Always in need of daughters—just as any French king needed them for diplomatic alliances—Napoleon incorporated another Beauharnais girl into the Imperial family in 1804, and gave her rooms in the Tuileries Palace. This was Stéphanie de Beauharnais (b. 1789), daughter of Hortense’s father’s cousin, Claude, Comte des Roches-Baritaud (see above). In 1806, she was created ‘Princess of France’, and like Eugène, she was deployed onto the martial chessboard to secure an alliance with one of the German princes, and married to Prince Karl of Baden, grandson and heir to the brand new Grand Duke of Baden. And like that of Hortense, her marriage it was not successful at first: he had little interest in her and lived in the capital, Karlsruhe, while she lived mostly in the old electoral palace in Mannheim. When he succeeded as Grand Duke of Baden in 1811, however, they came together with a common sense of dynastic duty: to produce a son. After three daughters, however, Grand Duke Karl died (1818), and Stéphanie spent a long widowhood—over 40 years—back in Mannheim. An interesting dynastic legacy was that through her daughter Marie-Amélie, who married the Duke of Hamilton, and in turn through her daughter, Lady Mary Victoria Douglas-Hamilton, the blood of the Beauharnais flows today in the house of Grimaldi in Monaco.

Matters took a sharp turn for all of the Beauharnais clan in January 1810, when Napoleon annulled his marriage to Joséphine so he might marry the Austrian Archduchess Marie-Louise. She retired to Malmaison, while Hortense was pushed aside as first lady of the court; after July of that same year, she wasn’t even the titular queen of Holland since that kingdom was abolished. Her life descended into scandal as she secretly gave birth to a son in Switzerland in 1811, named Charles Demorny, whose name apparently was ‘loaned’ by friends of Joséphine’s back in the French Antilles. Demorny’s actual father was the Comte de Flahaut, an aide-de-camp of General Murat, who was himself—it is supposed—the illegitimate son of the grand statesman Talleyrand. This uterine brother of the future Emperor Napoleon III would later in life re-enter politics and be elevated in rank as the ‘Duc de Morny’ (1862).

After her divorce, Joséphine was permitted to keep the title and rank of a crowned empress-queen and given a huge pension. She was created Duchess of Navarre, and given the estates of that name centred on a castle near Évreux, a town on the borders between the Ile de France and Normandy. The Château de Navarre had been built in the 1320s by the Queen of Navarre, Joan III, in the estates of her husband, a cousin of the royal family, Philippe, Count of Évreux. The castle passed with the county of Evreux back into the royal domain, and then in the 1640s into the possession of the La Tour d’Auvergne family, dukes of Bouillon, who rebuilt the château in the 1680s. It became property of the French state after the extinction of that family in 1801, then was acquired by the Emperor for his wife. The new Duchess of Navarre revived the château and spent time there to be far from the imperial court, quietly entertaining friends. After her death in 1814, she was succeeded in the duchy by Eugène and his sons, who sold the property in 1835; the castle was demolished. Later the Beauharnais family did put forward claims to the title ‘Duke of Navarre’ (in the 1850s), but the French government refused this as they were now seen as members of a foreign ruling house, so could not take the required oath to be a peer of France. The title was therefore considered extinct.

Also in 1810, a few months after the divorce, Eugène was named heir to another new state created by Napoleon, the Grand Duchy of Frankfurt, created out of the territories of the Imperial city of Frankfurt and the now secularised territories of the Archbishopric of Mainz. Its first grand duke was the last archbishop, Karl Theodor von Dalberg, who agreed that Eugène would succeed him when he died. Perhaps it was assumed that now that the Emperor had a new wife, a son would follow, who would be the proper heir to the Kingdom of Italy (as in fact happened, with the birth of the ‘King of Rome’ in March 1811). So it was best to get the growing Beauharnais family out of Italy—a son was indeed born to Eugène in 1810. As it happened, Dalberg ceded the Grand Duchy to Eugène before he died, in October 1813, but it was occupied by anti-Bonaparte forces in December, and by 1814 its territories were annexed by the Kingdom of Bavaria.

Despite the perceived great betrayal of his mother, Eugène de Beauharnais remained one of the most steadfast of all of Napoleon’s commanders—more so than most of the Bonapartes themselves, it has to be said. He led the Army of Italy to Russia in the epic campaign of 1812, then was left in command of the overall retreat, the army in tatters. He stayed loyal to his adoptive father in 1814, despite the defections of his father-in-law the King of Bavaria and his step-aunt Caroline Bonaparte and her husband Joachim Murat, the King and Queen of Naples. Eugène even fought against Murat’s Neapolitan troops near Parma, before he realised it was all over with the abdication of the Emperor in April. He retired to his father-in-law’s court in Munich, and renounced any further political activity. In particular, he did not support Napoleon during the Hundred Days (the attempt to restore the Empire, March to July 1815).

In contrast, Hortense, who had been warmly received by the restored King Louis XVIII in 1814, and even created Duchess of Saint-Leu in her own right, did support the Hundred Days, and was therefore banished from France after Waterloo. She settled at the Castle of Arenenberg, in the Swiss canton of Thurgau, on the banks of Lake Constance (purchased in 1817). In 1831, she would return to France with her son, Louis-Napoléon, in an attempt to overthrow the new government of King Louis-Philippe and restore a Bonapartist regime (Louis-Napoléon would eventually succeed in this goal, and became Emperor Napoleon III). Hortense was exiled again to Arenenberg where she died in 1837. This castle, originally built by a 16th-century mayor of the city of Constance, was eventually sold in the 1870s to the Canton of Thurgau which maintains it as a museum.

The brief duchy-peerage of Saint-Leu had been based on an estate Louis Bonaparte purchased in 1804 in the northwest suburbs of Paris. It included a château from the 1690s that had briefly been owned by the Duke of Orléans and his mistress Madame de Genlis in the 1790s. Hortense received the estate when she separated from Louis in 1810 (though he himself took the title ‘Comte de Saint-Leu’ once he was no longer King of Holland), and she hosted several glittering fêtes here. But after the fall of the Empire, the house and estate was returned to its original owners, the Princes of Condé, cousins of the King—and after the shocking death, possibly by suicide, of the last Condé prince in the house, it was demolished in 1837 and the estate sold off. It is possible that young Louis-Napoléon could call himself ‘Duc de Saint-Leu’ in the peerage of France, but once he became emperor any claims to this title were absorbed back into the state.

Meanwhile, Eugène de Beauharnais was swiftly incorporated into his wife’s family in Munich. In November 1817, he was created Duke of Leuchtenberg and Prince of Eichstädt, with the style of Royal Highness (since he had lost the style of Imperial Highness). He and his wife and children lived in the Palais Leuchtenberg in Munich, where the new Duke happily cultivated his art collection until his early death in 1824 at age 42. He lived just long enough, however, to see the first of his children re-enter the ranks of the highest levels of European royalty, when his daughter Joséphine married Prince Oscar Bernadotte (with equally French roots), heir to the thrones of Sweden and Norway. She became queen in 1844 and lived a long a full life in Stockholm.

The dukedom of Leuchtenberg had been an ancient imperial fief, originally a county (created 1158) held by an eponymous noble dynasty in the northeast quarter of Bavaria, near the mountainous borders with Bohemia. In the next generation the family von Leuchtenberg was raised to the rank of landgrave (a higher grade of count), and they maintained their semi-independence as holders of the largest secular fief within Bavaria until their extinction in 1646. The husband of the last heiress, Mechtild, was Duke Albrecht VI of Bavaria, youngest son of Duke Wilhelm V, so he was granted the landgraviate of Leuchtenberg in her name. But he soon ceded this to his brother Maximilian, the new reigning Duke of Bavaria, who in 1650 gave it to his son, Prince Maximilian Philipp and raised it to the rank of a dukedom. When this first Duke of Leuchtenberg died in 1705, the territory was absorbed into the Electorate of Bavaria. As a landgraviate it was given out once more by the Emperor in 1708 (during the War of Spanish Succession, when Bavaria was occupied), to the Austrian Lamberg family, in order to help them qualify fully as Imperial princes (since it was an immediate fief of the Empire); but it was returned to Bavaria at the end of the war in 1713. The castle of Leuchtenberg, one of the largest in what is called the Upper Palatinate, was built around 1300. It fell into disrepair after the extinction of its original dynasty in 1646, then was brought into a state of ruin by a major fire of 1842.

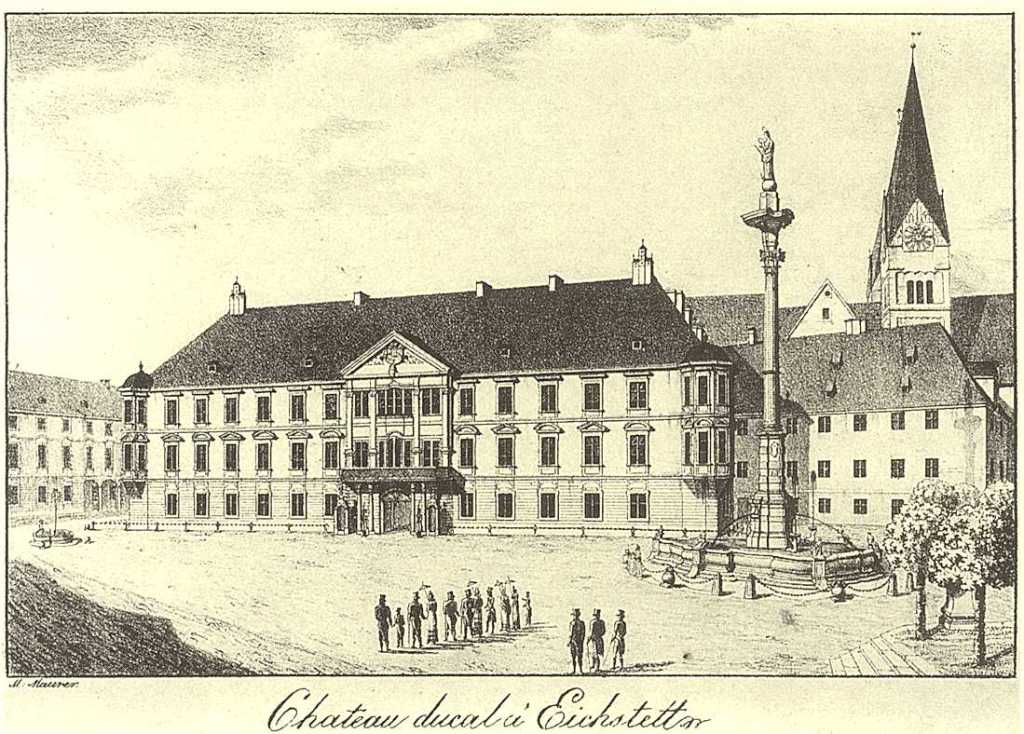

The Principality of Eichstädt (today spelled Eichstätt) was, like Leuchtenberg, a former imperial fief that was added to the territories of the House of Bavaria—in this case much more recently. The small town nestled in the valley of the river Altmühl, about halfway between Munich and Nuremberg, had been the seat of an independent bishopric since the 8th century, and formally a principality of the Empire from 1305. It was the home of an important Jesuit college from the 1560s (and is still an important Catholic university in Germany). Like all of the ecclesiastical territories of the Holy Roman Empire, it was secularised in the last years of the Empire’s existence, in 1802, and its lands were annexed by the new Kingdom of Bavaria. It was re-created as a principality for Eugène and his descendants, with large estates, about 20,000 ‘subjects’, and several castles.

The main residence of the family thus became the old episcopal palace in Eichstädt, built around 1700 (replacing an older medieval building). A short distance to the east was an episcopal hunting lodge (built about 1690), Schloss Hofstetten. Much closer to Munich and the royal court, the Leuchtenbergs were given a small castle called Ismaning, overlooking the river Isar northeast of the city. This had been the residence of the Prince-Bishop of Freising, whose lands were also secularised in 1802, and was rebuilt in a classical style by Eugène and his wife Princess Augusta. After the principality of Eichstädt was returned to the Bavarian Crown in 1833, Augusta remained at Ismaning, and after her death in 1851, it was sold. Later it was donated to the local municipality and today serves as the town hall.

In Munich itself, Eugène and his wife were given a plot to build on across an open square from the Royal Palace (or Residenz)—this was a new district of the city, just outside the old city centre and new aristocratic palaces here were meant to embellish the very grand new boulevard of Ludwigstrasse. The finest architects were chosen and the Palais Leuchtenberg arose, with neo-Renaissance style in emulation of Roman palaces, and over 250 rooms, a ballroom, a chapel, and so on. After Augusta’s death, the palace was sold to her nephew, Prince Luitpold of Bavaria. Badly damaged in World War II, the ruins were acquired by the state and demolished. It was rebuilt in the 1960s, using the old plans, and today houses the Ministry of Finance.

After Eugène de Beauharnais’ death in 1824, his son Auguste became the 2nd Duke of Leuchtenberg and Prince of Eichstädt—though he was only 14, so remained under the care of his mother and the rest of the Bavarian royal family. When he was 19, Auguste escorted his younger sister Amélie to Brazil where she became the second wife of Emperor Pedro I—and he was created Duke of Santa Cruz, in the peerage of Brazil (one of the few ducal titles connected to the New World; named for one of the imperial residences near Rio de Janeiro). Back in Europe, he was briefly considered a candidate for the new throne of Belgium in 1831, but not chosen. He had impressed his brother-in-law Emperor Pedro, however, and so in 1834 journeyed to Lisbon where the Emperor’s daughter (by his first marriage) had recently been installed as Queen Maria II. They married in December, and Auguste was created HRH Prince of Portugal. Sadly Auguste died only three months later. The familial link was maintained with Portugal, however, since the Empress Amelia had returned to Europe after the abdication of her husband in 1831, and she lived on in Lisbon until her death in 1873.

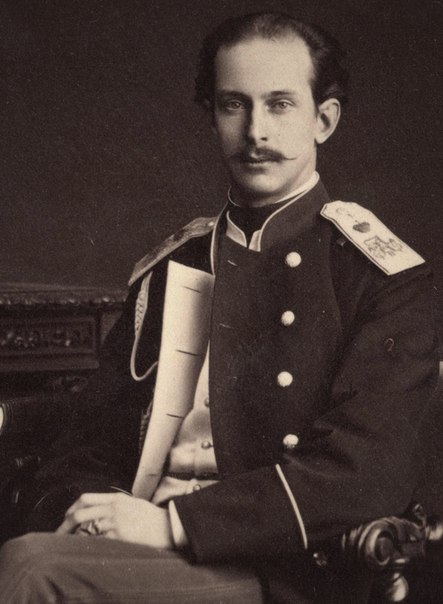

The Principality of Eichstädt was ceded back to the Bavarian Crown in 1833, but the Duchy of Leuchtenberg now passed to Eugène’s second son, Maximilien, again, still a teenager. When he was 20 his uncle the King of Bavaria sent him to Russia to take part in military manoeuvres. He was handsome and well-educated, and while he was there, attracted the attention of the Tsar’s daughter, Grand Duchess Maria Nikolaievna. They were wed two years later (1839) in Saint Petersburg, and were required to settle in Russia as Tsar Nicholas stated he could not bear to lose his favourite daughter. It was a love match, and Maximilian converted to Orthodoxy to satisfy the Russian court. In return, he was created Imperial Highness, and the couple was given a plot in Saint Petersburg a short distance from the Winter Palace where they could build a grand residence of their own. Finished in 1844, the Mariinsky Palace (or the ‘Palais Marie’ in French), across the square from St. Isaac’s Cathedral, became one of the major imperial residences and social gathering spots of the city. Today it is still a grand sight, and houses the Legislative Assembly of the City of Saint-Petersburg.

Now a Russian prince, Duke Maximilian of Leuchtenberg continued to pursue his passions, notably the study of mineralogy and the patronage of the fine arts. He became a member of the Academy of Sciences and President of the Academy of Arts in 1843. But his trips to survey mining operations in the Urals gave him tuberculosis and he died in 1852—the Beauharnais-Leuchtenberg men do not seem to live to great age! His widow Maria replaced her husband as President of the Academy of Arts—she remained an avid art collector and filled the Mariinsky with treasures. She raised her very young brood of children (the youngest, George, was only 9 months old) here and at their summer country estate Sergievka on the coast near Peterhof, where she and Maximilian had built the Palais Leuchtenberg shortly after their marriage.

But in 1854, Grand Duchess Maria secretly married her lover, Count Grigori Stroganov, and they moved abroad, settling in Florence from 1862. She had two more children and died in semi-disgrace in 1876. While this was going on, she sold the remaining estates of the family in Bavaria (1855). Her children were formally entitled Prince and Princess Romanovsky, to indicate their place in the Romanov family. They ranked as Serene Highnesses and their coat of arms was augmented with an imperial crown and placed against a Russian double-headed eagle. They were definitely Bavarians no more.

The new Duke, Nicholas (or Nikolai Maximilianovitch, Prince Romanovsky), was well placed to make a career on the European stage, related by blood or marriage to the royal families of Bavaria, Portugal, Sweden, and so on. In 1862, his cousin Otto of Bavaria, was deposed as King of Greece, and Nicholas was considered to replace him—as an Orthodox prince he was seen as a good candidate by the Greeks, but his Romanov blood made him suspect by the other Great Powers (notably Britain). It was a similar story when he was considered for the throne of Romania in 1866. Instead he followed his father’s footsteps and studied mineralogy, becoming the President of the Society of Mineralogy in 1865. In 1868, he fled Russia however, since his mistress Nadezhda Annenkova was pregnant. They wished to marry but she was denied a divorce from her first husband. It was a huge scandal. They married anyway, and lived abroad, where two sons were born, in Geneva and in Rome. They eventually settled in Bavaria at Schloss Stein (inherited from an aunt), until the Duke (alone) was restored to grace in 1877 and given a chance to resume his military career, as a lieutenant-general. Finally, in 1890, the marriage was recognised (as morganatic) and the sons were given the title Duke of Leuchtenberg, now a Russian creation (with the rank of ‘Highness’, ie not imperial or royal). The two boys, Nicholas and George, eventually did come from Bavaria to Russia, but not until after the deaths of their parents in 1891. We will return to them below.

The full imperial and ducal titles thus passed to the second son, Eugene (Evgeny). Unlike his sisters, Maria and Eugenia, who had married ‘properly’ into other European ruling dynasties (Baden and Oldenburg), the 5th Duke of Leuchtenberg followed his brother’s example and married for love. In 1869, he married Daria Konstantinova Opotschinina, who was created ‘Countess of Beauharnais’ by the Tsar. They had one daughter, then Daria died. He remarried in 1878, his wife’s first cousin, Zenaïde (‘Zina’) Skobeleva, but had no further children. The 5th Duke was very close to the Tsar, as he had been raised within the Imperial family after the departure of his mother (Grand Duchess Maria) for Italy in the 1860s, and rose through the ranks of the army, as Division General in the Russo-Turkish Wars of the 1870s, retiring as a lieutenant-general in 1886. His rank at court was raised from Serene Highness to Imperial Highness in 1890 (the same year as his brother’s sons were denied a similar styling), and his wife’s rank was raised to ‘Duchess of Leuchtenberg’ as well. His daughter, also called Daria, Countess of Beauharnais, lived well into the 20th century, but on a return visit to Russia in the 1930s she was arrested and executed.

After the death of Eugene, 5th Duke of Leuchtenberg and Prince Romanovsky, in 1901, these titles passed to his youngest brother, George. That same year, the new 6th Duke was considered, as now has been seen several times for this family, for a sovereign throne, this time the Kingdom of Serbia. Again his Russian blood was seen as both an asset and a problem, to different European powers, but his chances were boosted because he also had a Balkan wife, Princess Anastasia of Montenegro. Serbia had a coup in 1903, however, and the old dynasty was overthrown—the new king had a son and heir, so George of Leuchtenberg-Romanovsky was no longer needed. His marriage was also at an end, and in 1906 he and Anastasia divorced. He left her for a French mistress, and died in Paris in 1912. Anastasia remarried Grand Duke Nikolai Nikolaievich of Russia, a prominent imperial general and commander-in-chief of Russian forces at the start of World War I.

The 6th Duke’s elder son, Alexander, was born from a previous marriage, to Duchess Theresa of Oldenburg (who was herself already considered part of the Russian royal family, as her branch of the House of Oldenburg had moved to Russia at the very start of the 19th century). Alexander (or ‘Sandro’) was now 7th Duke of Leuchtenberg, and Captain of the Hussars of the Imperial Guard. In 1909 it was rumoured he was going to marry the daughter of US industrialist George Jay Gould, but nothing came of this. He did marry, in 1917, Nadezhda Carelli, but they had no children. Coming from one of the most connected princely houses in Europe, in March 1917, the Duke tried to get the British ambassador to Russia to help his Romanov cousins; then in 1918, he went to Berlin to seek aid from Wilhelm II. Neither of course was successful, and Sandro escaped to France where he settled in the Pyrenees near the southern border. He died there in 1942.

The 8th and last Duke of Leuchtenberg (of the Bavarian creation) and Prince Romanovsky (of the Russian creation) was the 6th Duke’s younger son (the child of Anastasia of Montenegro). As a young man, Sergei had been close to his step-father, Grand Duke Nikolai, served in the navy during World War I, and after brief capture by the Bolsheviks, participated in naval activities for the Whites in the Black Sea. He then settled in Rome. The 8th Duke never married and died in 1974, the last of the fully royal branch of the House of Beauharnais. His sister, Elena, had died in 1971, leaving as a widow Count Stefan Tyszkiewicz, from a Polish magnate family, who became a car designer in London. Their daughter, Countess Natalia, who died in 2003, was the last of the line. It would be interesting to know what, if anything, was left of the family fortune, whether she inherited any of it, and where it went after her death.

We do know that much of the fortune, including the Beauharnais collection of artworks, if not the princely titles, had already passed from the 4th Duke to his morganatic sons. As noted above, the elder of these sons, Nicolas, re-created as duke of Leuchtenberg by the Tsar in 1890, returned to Russia, sold off his possessions in Bavaria, and purchased a new estate at Gory, near Novgorod, and a mansion in Saint Petersburg. He was a major-general in the famous Preobrazhensky Regiment, and fought in the First World War. After the Revolution, and brief involvement in the Whites (the royal counter-revolutionaries) in Ukraine, he settled in the south of France—where he took up once more the old family title of Marquis de La Ferté-Beauharnais—at the Château de Ruth, in the Vaucluse near Orange, where he grew grapes and produced wine until he died in 1928 (since 2010, these wineries have belonged to another proprietor).

Brother George was also a captain in a Russian guards unit from the 1890s, and President of the Saint Petersburg Historical Society. After the Revolution, he settled at another old family property in Bavaria, the former monastery of Seeon, and wrote history books. He is perhaps best remembered as a host to Anna Anderson in the 1920s at Seeon, supporting her claims to be the lost Grand Duchess Anastasia, before she moved on to the United States. The former abbey of Seeon, founded in the 10th century, was built on an island in a lake in the southeast corner of Bavaria; secularised from 1803 and owned by the Leuchtenbergs from the 1850s until 1934, it is today owned by the state and opened as a cultural centre.

Both Nicholas and George had several sons. Of the younger line, Dimitry de Leuchtenberg (the name he used), moved to Québec and became a well-known promoter of the professionalization of the sport of skiing (d. 1972); his brother Constantine’s family settled in Ontario. Of the elder line, Nicolas settled with his uncle George at Seeon in Bavaria where he died (1937); while his younger son Sergei emigrated to the United States, his elder son Duke Nicolaus von Leuchtenberg, Marquis de La Ferté-Beauharnais (b. 1933), remained in Germany. He is a retired television engineer in Munich. The current head of the family had two sons, but only one, Constantin (b. 1965) is still living—he is unmarried, and none of the other branches have male heirs, so it is probable the entire House of Beauharnais-Leuchtenberg will soon be extinct.

(images Wikimedia Commons)

For the anonymous quarter….maybe…?

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Blason_de_la_Duchesse_de_Navarre.svg

LikeLike

Thanks Susana. Yes, I considered that, and there are similarities, but I don’t think enough. My guess is it is either something Napoleonic (like Arch-Chancellor of State) or something related to Bavaria (since it only appears after 1817 as far as I can see).

LikeLike

While I was researching the fate of the Leuchtenberg’s art collection I came across some interesting sources: Passavat, J.D. The Leuchtenberg Gallery. — Munich: 1852. Leikhtenbergski N. Vospominania. — Russkaya Starina, #5, 1890. Vrangel N.N. Karninnaya Galereia gerzogov Leihktenbergskich. — Niva. vol. 15. #574. 1884. Ctr. 1044-1073. etc.

LikeLike

https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/27992451/isabella-maria-picking

Any idea who this claimed Princess is? She is buried in Lake Forest, Illinois with an inscription on her headstone stating “princess von Leuchtenberg Countess of Beauharnais”

I could find no connection to the royal family,

LikeLike

She’s not on my lists, but t says on the site she was adopted. German law is strange in that anyone can adopt another person and give them their surname (and in today’s Germany a noble title is part of a surname). So that would be my guess.

LikeLike