One of the most powerful positions a woman could hold at any royal court, but particularly that of France, was the ‘recognised’ royal mistress, the open secret that everyone at court knew about. It was one of the only pathways for a woman to get a dukedom on her own in the ancien regime, as a means to recognise her ‘service to the crown’ and to ensure she could occupy spaces at court reserved exclusively for noblewomen of highest rank. Often the long-term beneficiary of these ducal creations, however, was the mistress’s male relatives. But in the case of two of Louis XIV’s mistresses, Louise de La Vallière and Françoise-Athénaïs de Rochechouart, Marquise de Montespan, these relatives had to wait for quite some time before basking in the glory of their family’s royal favourite.

Part of the reason for this was that Louise and Françoise-Athénaïs differed significantly from each other in terms of the world of dukes and princes: Louise was unmarried, but Madame de Montespan had a husband. This meant that Louise could be given a duchy (Vaujours, later called La Vallière) directly, whereas it would have been awkward to give one to Françoise-Athénaïs, since it would have elevated her husband too (and the Marquis de Montespan by law could even have claimed Louis XIV’s illegitimate children as his own). So while Louise’s duchy was eventually passed on to her nephew, Charles-François de La Baume le Blanc, Madame de Montespan’s male children by the King were given their own duchy-peerages directly (Aumale, Penthièvre, and so on), and only in 1711 was her legitimate son (ie, with her husband), Louis-Antoine de Pardaillan de Gondrin, raised in rank to Duke of Antin. In part, both dukedoms, La Vallière and Antin, were created to recognise a degree of kinship—in a roundabout way—that these men would share with the future king of France.

The families who held these two dukedoms were also different. Louise came from a relatively minor and relatively new noble family from the Loire valley, La Baume Le Blanc, whereas the family of Françoise-Athénaïs, Rochechouart, was prominent and ancient (see a separate blog post on them), while the family of her husband, the Marquis de Montespan (the Duke of Antin’s father), Pardaillan de Gondrin, were equally much more prominent at court, and their roots as provincial nobles stretched back to the very earliest days of the French monarchy.

So we can start with the House of Pardaillan, deep in the south of France, in the province of Gascony. It was a fief of the semi-autonomous county of Armagnac. This county was subdivided into baronies, and Pardaillan was one of the oldest of these. The castle of Pardaillan, today in the region of Condomois (in the modern départment of the Gers), dominated a hamlet just outside the town of Beaucaire, on the river Baïse, which flows north out of the Pyrenees to join the mighty Garonne on its way to the Atlantic. Also spelled Pardailhan or Pardeilhan, the castle probably takes its name from an ancient owner, Pardalius, which seems to relate to the word for panther or leopard. There is evidence of a villa here from the Merovingian period at least (6th or 7th century). The medieval castle was built in the early 14th century, and when the family split in the 13th century, it was kept by the senior line until it died out in the early 17th century. The castle of Pardaillan passed into other hands and fell into ruin, and its remains were pulled down in the Revolution.

A short distance to the northwest is the château of Gondrin, erected as a small fortress in the 14th century, the period when this region was ravaged by French and English armies in the 100 Years War. It became the main seat of the now secondary branch of the family. It was redeveloped as a more grandiose château in the early 17th century, but little remains today. Another of the family’s properties built nearby was Beaumont, also improved in the late 17th century, survives today as a model of French baroque style. Today it is the home of writer and television/radio producer Ève Ruggieri, whose parents restored it from a ruined state. The château hosts summer classical music programmes, and its châtelaine has made a point of celebrating the connection with Madame de Montespan, though I wonder how much time the famous royal mistress would have actually spent there.

The earliest members of the noble house which used both names, Pardaillan and Gondrin, appear in the 11th century, but details are patchy until the 13th, when one, Hugues, rises to local prominence to become Bishop of Tarbes (1227) and Archbishop of Auch (1244)—both major ecclesiastical powers in the far south of France. A nephew, Bernard, Lord of Pardaillan and Gondrin, established his family’s credibility as Christian warriors by accompanying Louis IX on his crusade to Tunis in 1270. Others served more locally in the wars led by their feudal lord, the Count of Armagnac.

Several offshoot branches were founded in the Middle Ages, and more lordships were acquired by the branch of Gondrin, notably the lordship of Castillon (c. 1400), in the area downriver from Bordeaux known as the Médoc (now on the edge of the village of Saint-Christoly). Its incredibly ancient tower still stands, though it has served as a home for pigeons (a pigeonnier) since the 18th century. The coat-of-arms for this family, three moors’ heads over a castle, were added to the wavy blue and white lines of the Gondrin arms.

In 1521, Antoine de Pardaillan, Baron de Gondrin and Viscount of Castillon, married Paule d’Espagne, daughter of the Lord of Montespan. Montespan was much further south in a county called Comminges, quite close to the Pyrenees (see map above). A local noble family said to be a cadet branch of the counts of Comminges took the name ‘Mont d’Espagne’ in the 13th century, and this evolved into Montespan. Antoine assumed the title Baron de Montespan and added the family’s red lion with several small green escutcheons to his own coat-of-arms. He raised the family profile higher through military service in the region, first for the King of Navarre (for whom he also acted as governor and seneschal of that king’s core lordship of Albret, a short distance to the west of Gondrin; and his brother was appointed governor of the neighbouring county of Armagnac), and later for Charles IX in the fight against Protestant rebels in the south of France.

Antoine and Paule had a son named Hector, Baron de Montespan, who became Captain of the King’s Guard and a Councillor of State. He too married yet another heiress, Jeanne d’Antin, in 1561, whose lordship of Antin was also situated in one of the ancient Pyrenean counties, this time Bigorre, to the west of Comminges, which bordered on the sovereign principality of Béarn. This castle too probably took its name from an ancient owner, someone named Antinus. In the Middle Ages, the County of Bigorre belonged to the Count of Foix, which like Béarn, was a semi-sovereign territory. Only after 1607 therefore were these lands, and thus Antin, formally united to the Kingdom of France.

Antin was raised to the status of a marquisate in 1612, as was Montespan three years later, for Antoine-Arnaud de Pardaillan de Gondrin. He had long been a devoted soldier in the service of his fellow Gascon, King Henry IV, and commanded his armies when the King attended to other business away from the front. The King in turn appointed the Marquis Governor of Navarre and Béarn, and later of Agenais and Condomois, sub-regions of Aquitaine (over which he acted as the King’s Lieutenant-General). At court, Antoine-Arnaud was Captain of the Premier Company of the King’s Guard and a member of the Privy Council. His career was crowned with the award of the Order of the Holy Spirit in 1619, the highest order of knighthood in France. By his first marriage, the first Marquis de Montespan had two daughters, through whom he secured kinship relations with two of the leading families of the far south: Albret and Foix. By the second marriage, to Paule de Saint-Lary, sister of the Duke of Bellegarde, one of the great war companions and favourites of Henry IV, he added even further to his family’s patrimony—though not right away.

Paule de Saint-Lary’s son Jean-Antoine was ultimately heir to her brother the Duke of Bellegarde, when he died in 1646; and for good measure, Jean-Antoine married his first cousin, the daughter and heiress of his mother’s other brother, the Baron de Termes, in 1643. Although the Saint-Lary family, like the Montespans, came from Comminges, their duchy of Bellegarde (cr. 1619) was based on the town of Seure on the Saône river, the frontier between Burgundy and Franche-Comté (which until the 1670s was still an international frontier). By 1645, that property had been sold to the Prince of Condé, so the title ‘duchy-peerage’ was transferred onto another property in Gâtinois (the flat plain between Paris and the Loire valley), Choisy-aux-Loges, which had been acquired by the old Duke just before he died in 1646. But the attempted transfer of the duchy-peerage (the title, not just the land) took place in the confusing days of the Regency of Louis XIV, and was never formally recognised by the Parlement of Paris. The other Saint-Lary property added at this time was Termes (or Thermes), another lordship in Comminges, which therefore added to the family’s already extensive lands in that province.

There had been a château at Choisy (or Soisy; with the added name of –aux-Loges indicating its position in the forest of that name) since the mid-14th century. It was the seat of the powerful de l’Hôpital family in the 15th and 16th century, and was rebuilt by one of its most prominent members, who became Marquis de Choisy. After Roger de Saint-Lary acquired it and tried to transfer his duchy-peerage onto it, the name of the castle and the village was changed to Bellegarde; it remained in the possession of Jean-Antoine’s widow, Anne-Marie, until she sold it to her great-nephew Louis-Henri, Marquis de Montespan (below). After he was created Duke of Antin, he made it his main residence and greatly enlarged it, on a scale more appropriate for a duke—in the 1720s he added two wings housing a new chapel and a gallery to display his art collection, plus a grand stable with its own triumphal gate complete with sculpted horses’ heads attributed to the famous sculptor Antoine Coysevox. In the 1770s, the Château de Bellegarde was purchased by a President of the Parlement of Paris (Pierre-Paul Gilbert de Voisins), who took the title Marquis de Bellegarde. Today the château is managed by the town which in recent years has invested in opening up its spaces in the gardens and the ancient donjon for tourism.

Jean-Antoine, 2nd Marquis de Montespan (and sometimes called, unofficially, ‘Duc de Bellegarde’), had been raised by his uncle Bellegarde as his heir, and already from the 1620s was taking over his uncle’s familiarity with the royal family, becoming one of Louis XIII’s Masters of the Wardrobe at court, and his Lieutenant-General in Armagnac, Bigorre and Comminges. Meanwhile two of his brothers (known as the Marquis d’Antin and the Marquis de Termes) were placed in key positions in the household of the King’s brother, Gaston, Duke of Orléans; still other brothers were put into the Church or the Order of Malta. One of these, Louis-Henri de Pardaillan, rose through the church hierarchy to become Archbishop of Sens, one of the most important positions in the French church, in 1646. He died as a fairly old man in 1674, while his eldest brother the Marquis lived even longer and died at age 85 in 1687. It’s interesting to think these two throwbacks from the very early decades of the century were still alive during the ascendancy of Madame de Montespan.

It was thus the 3rd Marquis de Montespan, Louis-Henri, who became the famous cuckold of Louis XIV, not too long after he had married one of the beauties of the French court, a daughter of the Duke of Mortemart, in 1663. This marriage brought him not only prestige, since the Rochechouarts were one of the oldest and most eminent noble houses in France, but also badly needed cash. His uncle still held the bulk of the family properties; but ceded the title Montespan to his nephew as heir; Louis-Henri also inherited the marquisate of Antin from his father, Roger-Hector, who had died when he was still very young. Like his uncle, this Marquis de Montespan also had a number of brothers who made use of the family’s numerous titles (again one was Marquis d’Antin and the other Marquis de Termes), while others were placed in the Order of Malta. Curiously, his mother, Marie-Christine Zamet (granddaughter of the famous Italian financier, Sebastiano Zametti), was part-heiress of yet another major southern family, that of Nogaret de la Valette, whose principal dukedom of Epernon had been created for one of the favourites of King Henri III in 1581. The Nogarets were also closely related to the Saint-Lary de Bellegarde family, so this was another part of this large coalition of properties held by this noble kinship group in the far south of France. The Duchy of Epernon itself however was not in the south, but based on a property near Chartres, and it is primarily this estate which the Pardaillan family was able to grab for itself after the death of the last duke in 1661. So, if Louis XIV had been feeling more generous towards Louis-Henri at the time he was creating lots of duchy-peerages (the early 1660s), the future mistress might already have been either Duchess of Bellegarde or Duchess of Epernon.

But Louis XIV did not particularly care for the Marquis de Montespan, and particularly once he wanted him out of the way due to his affair with his wife, from about 1666. At that time, both the Marquis and the Marquise served in the household of Madame, Henriette-Anne of England, Duchess of Orléans (the King’s sister-in-law), he as chevalier d’honneur and she as a lady-in-waiting. They had two small children, Marie-Christine and Louis-Antoine, and lived in a small house near the Louvre. Montespan’s debts, despite his wife’s large dowry, pushed him to pursue military commands, so he went to serve in the army occupying Lorraine and then on the expedition to North Africa in 1664. When the King sent him on another mission far away from court, this time to the Spanish frontier, he became suspicious, and in 1667 his fears were confirmed when his wife became pregnant. The Marquis re-appeared at court and made a loud scandal—some sources say he rode around town with cuckold’s horns; others say he deliberately tried to get a venereal disease from a prostitute to then pass on to the King via his wife. He was briefly imprisoned in Paris for publicly insulting the King, then retreated to Gascony, taking his children with him. Here he stayed until he died in 1691 (though some sources say 1702).

In Gascony, the Marquis de Montespan and his children lived at the Château de Bonnefont, an old family property in Bigorre on the river Baïse. Here Marie-Christine died as a teenager—supposedly from grief from missing her mother. At Bonnefont, Montespan is said to have organised a grand funeral ceremony, including interment, for his lost love. He considered himself a virtual widower. This ancient castle had an air of elegance in its newer buildings. By the 19th century it was sold to a religious order who opened a school—it then went through several versions of college or training centres, and today hosts a school for mentally handicapped children. Its main tower, facing collapse, was dismantled in 1972.

Meanwhile, in Paris, Madame de Montespan was the virtual queen of the court, as a much more dominant personality than the actual queen (Marie-Thérèse of Spain). She and the King had four children that survived childhood: the Duke of Maine, Mlle de Nantes, Mlle de Blois and the Count of Toulouse. In 1674, she obtained a legal separation from her husband, mostly to protect these children’s future inheritance, for example the beautiful château she built near Versailles, Champs, which ultimately passed to the Duke of Maine. From 1677, however, her star was falling, partly due to her involvement in the Affair of the Poisons. Louis wanted to give her the normal ‘parting gift’ of a duchy, but, not wishing to elevate her husband, he named her Superintendant of the Queen’s Household—the top position for a woman at court—with the right to sit in the presence of the Queen, as if she were a duchess. By the 1680s she was definitely out of favour, and in 1691 she retired from the court altogether to a convent in Paris.

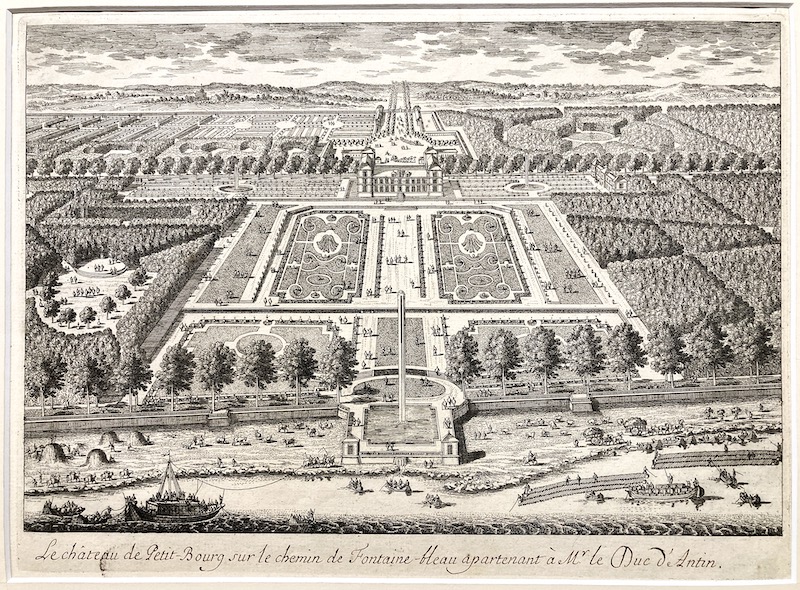

In 1695, Madame de Montespan purchased a house in the town of Evry, on the heights above the Seine southeast of Paris (on the road to Fontainebleau), as a retreat for herself, Petit-Bourg. When she died in 1707, it passed to her son, Antin, who reconstructed it on a grander scale from 1716, notably its gardens, and when his line died out in the 1750s, it was purchased by the widow of a Parisian official who demolished it and built another—the neoclassical building seen until 1944, when it too was destroyed.

Montespan’s son also inherited the lordship and château at Oiron, in Poitou, south of the Loire (not far from the Abbey of Fontevraud). This was a much grander country house, the seat of the Gouffier family who rose as royal favourites of King François I in the early 16th century. It was the site in particular of one of the most spectacular art collections of the Renaissance. When the Gouffier family (dukes of Roannais) died out in the 1660s, their titles and artworks passed to the Marshal de la Feuillade, who refurbished and modernised it in the 1670s, then sold it to Montespan for her son in 1700. It became one of her preferred residences at the end of her life, but her son preferred Bellegarde and Oiron fell out of use. Indebted, Antin’s widow sold it in 1739 to the Duke of Villeroy—after that it passed through various hands, largely restored in the late 19th century and today open as a museum.

Much of the Marquis d’Antin’s career was, naturally, promoted by his mother. Even though her star was in the wane after 1680, she brought young Louis-Antoine to court from Gascony in 1683, secured him a military commission, but more importantly, drew him into the circle of the (then assumed) future king, the Grand Dauphin, by marrying him to the grand-daughter of the Dauphin’s old governor, the Duke of Montausier. He also became close to his and the Dauphin’s half-brothers, the illegitimate sons of the King. The year of Antin’s marriage (1686) he was appointed Lieutenant-General of Upper and Lower Alsace, the military equivalent to the governor of the province, but failed to make more of an impact at court until after his disgraced mother died in 1707. In that year he was appointed Governor of Orléannais, a more substantial province (and closer to court) than Alsace; and the next year was named Superintendent of the King’s Building Works. This was an unusual appointment for a noble grandee—normally it was held by one of the King’s lower-ranking ministers—but it brought Antin great access to the King who loved his building projects, and also gave Antin access to all the King’s greatest architects and designers, whom he employed on his own projects at Petit-Bourg and Bellegarde. It turned out he was a very good organiser, and helped Louis XIV and then Louis XV on their various building projects at Versailles and other royal sites. Antin also built his own grand residence in Paris, the Hôtel d’Antin, in the area just on the northwest edge of the old city, in the district now close to the grand department stores. The house no longer stands, but one of the streets in the area bears its name, the Chausée d’Antin.

Finally, in 1711, Louis-Antin was raised to the peerage always denied his father. It was called Antin, not Montespan, and was based on the marquisate of Antin, which had four baronies joined it to form the dukedom, including the barony of Miélan, on the borders between Bigorre and Armagnac, which, due to its situation on the main road between Tarbes and Auch, became its main administrative centre, though it was never a ducal residence. Closer to court, he also held the estates of the duchies of Bellegarde and Epernon, both conveniently located quite close to his government in the Orléannais and the Loire Valley.

Before we follow the 1st Duke of Antin’s children into the 18th century, we should look closer at the Loire Valley and the family of Madame de Montespan’s rival, Louise de La Vallière.

****

Compared to the family of Pardaillan de Gondrin in Gascony, Louise’s family had its roots much closer to the royal court, particularly when French kings spent more of their lives in the Loire Valley in the 16th and early 17th centuries. The family of La Baume Le Blanc de La Vallière were prominent nobles in the town of Tours—not far from favourite royal residences at Blois and Amboise—and held lucrative estates north of the river in Touraine. It was this proximity to royal residences that first brought Louise de La Vallière to the attention of the Bourbons in the 1650s, as we will see.

The Le Blanc family were originally from the Bourbonnais, with estates on the borders with the province of Berry. Here they had a castle called La Baume, on the left bank of the river Allier, and they eventually added La Baume to their surname. The term ‘la baume’ itself comes from local patois for a rocky outcropping. In the Bourbonnais, a castle was built in the 14th century, and held by the Le Blanc family who were also captains of other local castles for the dukes of Bourbon. The earliest member of the family in most family trees is Perrin Le Blanc who commanded the arrière-ban of the feudal armies of Bourbonnais and Auvergne against the English in 1425. But by about 1550, the senior line of the family died out, and the junior line, rising to greater prominence, was now based in Touraine. The ancient castle of La Baume was sold; what is there today was built by different owners, in the mid-18th century.

Like many families from the more minor provincial nobility of the 15th century, the pathway to a rise in power and wealth was often through service in the judiciary system. Laurent Le Blanc de La Baume, the youngest son of Perrin, thus moved to Paris and became a procureur (a public prosecutor) at the Châtelet, the main law court for the city of Paris. He acquired his own lordships close to the capital, Choisy-sur-Seine and Puiselet.

It’s an interesting coincidence, but just a coincidence, that both of these two families of royal mistresses were associated with a lordship called Choisy, and in fact this one is associated more in people’s memories with a third mistress, Madame de Pompadour. This Choisy was close to Paris, in the district to the south and east in which many of Paris’ elite judiciary and financial families built country homes to get away from the stench of urban streets. The medieval lordship of Choisy, on the Seine, had initially belonged to the Abbey of Saint-Germain-des-Prés in Paris. After its time in Le Blanc de La Baume hands, it became a property desired by royals: in 1678, it was purchased by Louis XIV’s cousin, the Duchess of Montpensier (aka, ‘La Grande Mademoiselle’) who built a new château here for herself and developed its gardens; this passed by inheritance to the Dauphin when she died in 1693, and he soon exchanged it for the château of Meudon closer to Versailles. It was then purchased in 1716 by the Dowager Princesse de Conti, daughter of Louise de La Vallière—another coincidence? or was she conscious that it had once belonged to her mother’s family? At her death in 1739 it was acquired by Louis XV, and it became one of his favourite hunting grounds. It was this King who installed Madame de Pompadour here once she was firmly placed as his mistress in 1746. Considered to be one of the most beautiful baroque palaces of the age of Louis XIV, Choisy (at this point renamed Choisy-le-Roi) was mostly destroyed in the Revolution.

Jumping back to the end of the 15th century, Laurent Le Blanc de La Baume’s eldest son Hugues also became a public prosecutor in Paris and married the daughter of one of the head officials at the Châtelet, while his daughter married into another one of Paris’s leading families, the Séguiers. A second son did what second sons do and joined the army—and was killed in battle in northern Italy in 1525. The two youngest sons neither stayed in Paris nor joined the army, but acquired rural estates in Touraine, and by the 1530s shifted the family focus south to the Loire valley.

Another Laurent Le Blanc, son of Hugues, acquired the lordship of La Vallière in Touraine in about 1542. Over the next two decades he acquired several other nearby lordships. And he continued to serve the Crown: as a royal secretary, as master of the household of Queen Eléonore (wife of François I), as tax collector for the province of Maine (next to Touraine) and a high ranking tax official for the city of Bordeaux. In 1558 he was elected to serve a year’s term as Mayor of Tours. But though he did ‘work’ in finance and governance, he also made sure to submit his proofs of nobility in 1550 to ensure his status and privileges as a nobleman (ie, someone who did not ‘work’). His residences proudly bore a noble coat of arms, the distinctive La Baume Le Blanc shield sporting a leopard rearing on its hind legs divided horizontally into two halves, silver and black, against an equally divided field of red and gold.

The château at La Vallière was rebuilt at about this time, replacing an older fortress from the 14th century. Set in a wooded valley northeast of Tours, near the town of Reugny, its location close to Amboise, Chenonceaux and other famous castles of the Loire Valley made it a highly prized residence for the family in the 17th and 18th centuries, and for their successors in the 19th century (dukes of Uzès then counts of Rougé). It was owned by various others until it was converted into a luxury hotel in 2018, the ‘Château Louise de la Vallière’.

Meanwhile in the city of Tours itself, Laurent II built the Hôtel de la Vallière, in a very central location on the Grand Rue, with gardens behind leading down to the banks of the Loire. This grand house was the scene of much history in Tours: Laurent’s sons received King Henri III here in 1589 after he was chased from Paris by the forces of the Catholic League, and then the next king, Henri IV, later that same year when he was preparing to march north to claim his capital. Louise was born here, but it was sold soon after, in 1655, and became known as the Hôtel de la Crouzille. The house was destroyed in 1940, though elements remain.

Laurent’s son Jean maintained the family’s balance between office-holding in Tours and positions in the royal household: he was Master of the Household and Secretary of the Duc d’Alençon (Charles IX’s younger brother), 1567, then Master of Household of Alençon’s mother, Queen Catherine de Medici, 1579, later filling that same role for Henry IV, 1589, then his divorced wife, Queen Margot—he remained in her household as chevalier d’honneur as late as 1610. In Tours he was Mayor in 1588 and commander of the royal residence on the edge of the city, Plessis-lès-Tours. Jean Le Blanc continued his link with the world of royal finance as well, as Director-General of Finances for Languedoil (ie northern France) and Intendent General of Finances for one of the royal armies in 1590. His wife Charlotte Adam de La Gasserie, daughter of another Master of the Household of the Queen Mother (Catherine de Medici), was herself a Dame d’honneur to the same queen. But Jean and Charlotte had no children, so their estates passed in the next generation to their nieces and nephews, children of another Laurent Le Blanc, and Anne’s younger sister, Marie Adam, heiress of the lordship of La Gasserie, nearly adjacent to the lordship of La Vallière in Touraine.

By this point, the family were pursuing more purely ‘noble’ careers, in a typical scenario seen in provincial noble families who grew rich and influential from service to the royal court: the eldest, Laurent III, joined the army and was killed at the siege of Ostende in 1602. The second son Jean thus took over as head of the family, and secured their advance in the noble hierarchy through a marriage in 1609 to a daughter from one of more prominent families in this region, Françoise de Beauvau. From early posts as equerry in the royal stables and gendarme in the Company of the Dauphin in 1609, he became governor of the château of Amboise and of the city of Tours, and eventually the King’s lieutenant-general in Amboise, 1639. His own children did not look back at all to the world of finance, and made marriages entirely within the nobility and forged careers in the military or the church. Of the clerics, Gilles was a canon in the Cathedral of Saint-Martin in Tours, then rose to become Bishop of Nantes in 1667; while Jacques became a Jesuit who died on a mission to the West Indies. Of the older sons who joined the military, three were killed in various battles of the Thirty Years War—one of these, François, Chevalier de La Vallière, was on the cusp of being named Commander of French forces in Catalonia in 1646 when he was killed in the siege of Lerida.

The eldest son, Laurent V, continued in his father’s post as the King’s Lieutenant in Amboise. By this point, the 1640s-50s, the uncle of the young Louis XIV, Gaston, Duke of Orléans, was living mostly at his preferred residence nearby at Blois, and spending much of his time socialising in Tours. It was this opportunity that Laurent and his wife Françoise le Prevost seized to place their daughter Louise into the household of Gaston, as a companion to his daughters of the same age. After both Gaston and Laurent’s deaths, the widow La Vallière stayed connected to the royal family by re-marrying the Marquis de Saint-Remy, Master of the Household of the now Dowager Duchess of Orléans (Marguerite de Lorraine). It was this connection that brought young Louise to court in 1662, where she was placed in the household of the new Duchess of Orléans (Henrietta Anne of England) as a fille d’honneur. And from here, she was spotted by the King and soon became his first principal mistress.

In 1666, Louis XIV acquired a lordship in Touraine not too far from La Vallière called Vaujours, and in 1667 he joined it to La Vallière and the nearby lordships of Châteaux and Saint-Christophe to form a duchy. The royal genealogist of the period, Père Anselme, says that Châteaux was the premier barony of Anjou, while Saint-Christophe was the premier barony of Touraine, meaning these were all pretty significant estates. The resultant duchy of Vaujours, aka La Vallière, was created with a peerage for Louise and for her daughter, Marie-Anne de Bourbon, known as ‘Mlle de Blois’ until she married the King’s cousin, the Prince of Conti. In 1674, Louise left court and entered a Carmelite convent in Paris, taking the name ‘Soeur Louise de la Miséricorde’—to try to wash away her sins of adultery. She left the duchy of Vaujours to her daughter, who enjoyed its revenue and the chief residence at La Vallière until she in turn donated it to her first cousin, the Marquis de La Vallière. Louise lived in her convent until she died in 1710; her daughter the Dowager Princess of Conti lived well into the reign of Louis XV and died in 1739.

The ‘other’ château at the heart of the duchy (and confusingly, the nearby village is today called ‘Château-la-Vallière’) was the château de Vaujours, across the border from La Vallière (in Touraine) in the neighbouring province of Anjou, within the lordship of Châteaux. Also nestled in a forested valley (the ‘Val-Joyeux’ which gave it its name), this castle had been built as a defensive structure in the early middle ages when the counts of Anjou were often at war with the kings of France who held neighbouring Touraine. The local Alluye family fortified the château in the 15th century against the English, and with its two moats, it was nearly impregnable, never taken. It then passed to other powerful families of Anjou until the Bueil family sold it to Louis XIV in 1666, as above. In the 19th century, it was sold to an English aristocrat, Thomas Stanhope Holland, but it soon fell into ruin. When I visited the area a few years ago it was dilapidated and closed to the public, but I have read that it has since been spruced up and re-opened.

There were only two dukes of La Vallière: Charles-François, Louise’s nephew, and his son. Charles-François was the son of Jean-François, Louise’s brother, who had started to rise to great heights through his sister’s royal favour, as Governor of the Bourbonnais from 1670, and Captain-Commandant of the Light Cavalry in the regiment of the Dauphin. But he died at only 34 in 1676, leaving everything to his two sons.

Charles-François was thus an orphan at age 6. Nevertheless he succeeded his father as Governor of the Bourbonnais (though actually administered by his cousin and surrogate mother, the Dowager Princess of Conti). Like Montespan’s son, he was placed in the household of the Dauphin and was signed up to be a musketeer to learn his trade in the military. By 1692 he was commander of his own cavalry regiment, and he led these in battle (now as a brigadier general) in the War of Spanish Succession, notably at the Battle of Blenheim in 1704. He was then promoted field marshal, and lieutenant-general by 1709. In 1698, the Dowager Princess of Conti ceded him the Duchy of Vaujours; Louis XV re-erected it more formally into a peerage in 1723 and changed its name to La Vallière. Also in 1698, the Duke of Vaujours married Marie-Thérèse de Noailles, daughter of the 2nd Duke of Noailles—one of Louis XIV’s more successful generals—whose brother married that same year the niece and designated heiress of the last of Louis XIV’s mistresses, Madame de Maintenon. So now all of them are getting into this story (and we’ll see the Noailles family again below).

The Duke and Duchess of La Vallière lived at Champs, another of the small pleasure palaces popping up all around the Isle de France in this period. Champs was situated on the banks of the river Marne, east of Paris. It had been an ancient fief of the Montmorency family, then held by various others in the 17th century, before it was purchased by one royal financier, Renouard de la Touraine, who built a new château here, then by another, Poisson de Bourvallais, after the first was caught doing financial misdeeds and had his lands confiscated. The latter of these also had his properties confiscated in 1716, and the Crown sold it to the Dowager Princess of Conti, who immediately ceded it to her cousin the Duke of Vaujours. Champs was leased to Madame de Pompadour in the 1750s, and it is she who is still commemorated there, as a historical site restored in the 1890s by its aristocratic owners and turned over to the state in 1935. It has again been wonderfully restored in the last decade and re-opened to the public.

The 1st Duke of La Vallière resigned his peerage to his son, Louis-César, in 1732—though the 2nd Duke used the title Duke of Vaujours until his father died in 1739. The younger Duke hosted a regular literary salon at Champs, and was a close companion of Louis XV and later of Madame de Pompadour to whom he later (in the 1750s) leased this property. He himself focused instead on developing another property, Montrouge. This new château was built in close proximity to royal hunting grounds on the flat plain just south of the city of Paris. La Vallière’s royal favour through a shared love of the hunt was strengthened by his appointment as Grand Falconer of France in 1748, and Captain of the Hunt at Montrouge. His new château there also hosted his growing collection of books–which were the focus of some major book sales after his death. Most of the town of Montrouge was annexed to the City of Paris in 1860, and the crumbling chateau was demolished in the 1870s to make way for a new town hall.

The 2nd Duke of La Vallière was, like his father and grandfather, governor of their family’s ancient home province, the Bourbonnais. He was a brigadier in the army, but not a particularly noteworthy commander. He lived until 1780, as a recognised bibliophile and patron and protector of poets and playwrights. When he died his properties passed to his only daughter, Adrienne-Emilie, who married the Duke of Châtillon. As a widow, she called herself the Duchess of Châtillon and La Vallière, though the peerage was in fact extinct from her father’s death. From here, the properties in Touraine passed through another daughter into the House of Crussol, dukes of Uzès.

****

Returning to the descendants of Madame de Montespan, we see this same family marrying one of its co-heiresses in the mid-18th century into the House of Crussol d’Uzès, as well as another marriage with the family of Noailles—the sister of the 1st Duchess of La Vallière, above, was set to become the 2nd Duchess of Antin, but her husband died long before his father, the 1st Duke—Montespan’s son. But she (Marie-Victoire de Noailles) went on to marry the Count of Toulouse in 1723, tying the Pardaillan family even closer to the King’s illegitimate sons. (in fact she had to keep this marriage a secret at first, since marrying your late husband’s father’s half-brother—so, half-uncle?—was dangerously close to the edges of the incest laws). The Countess of Toulouse remained a powerful figure in the early days of the reign of Louis XV, filling in for the mother he never knew. It was thus good to have her in the Antin corner.

Louis-Antoine, 1st Duke of Antin had been well set up in his career by the time Louis XIV died in 1715. As someone who was so closely related to the royal family, and who was already proving himself as a skilled administrator (as Superintendent of the King’s Buildings), he was an easy choice by the Regent, the Duke of Orléans, for a seat on the Regency Council, and in particular as head of the Sub-Council of the Interior. Antin remained on the Regency Council until it ended, when Louis XV came of age, in 1722, then retired to the countryside. By that point his son Louis had died (1712, age only 24) so he ceded his peerage in 1724 to his grandson, also named Louis. The 1st Duke died in 1736.

Louis, 2nd Duke of Antin, was also called ‘Duke of Epernon’, as successful claimant to the lands of that duchy near Chartres (see above). He and his brother were looked after by their mother, now Countess of Toulouse, and by their uncle, Pierre de Pardaillan, who also in 1724 became Bishop of Langres, one of the premier bishoprics (with the rank of duke) in France. The 2nd Duke’s younger brother, Antoine-François, became Governor of Alsace and a Vice-Admiral in the Atlantic fleet. But like their father, neither the 2nd Duke nor his brother lived very long, both dying in their thirties.

This left only one son, three sisters, and two widows. The 3rd Duke of Antin, Louis, lived only 20 years and died in Germany in 1757. His eldest sister, Julie-Sophie, became Abbess of Fontevraud, one of the most famous abbeys in France, in 1765—she would be the last head of this prestigious royal convent, as it was shut down during her tenure in 1792. The other sisters were co-heiresses of the vast estates of the Pardaillain de Gondrin, Saint-Lary de Belleville and Nogaret d’Epernon families. One married the Marquis de Civrac and the other her cousin the Duke of Uzès. Although there were distant cousins of the Pardaillan family living in the provinces that continued on into the modern era, by 1780 both families of the Dukes of Antin and La Vallière, the kin of royal mistresses, were extinct.