At the end of Part I, in 1530 the Prince of Orange, Philibert de Chalon, left his possessions, including the principality of Orange in Provence, and lands in the Free County of Burgundy, to his sister’s son, René of Nassau, whose family–later called the House of Orange-Nassau, would dominate the history of the Low Countries for the next four centuries.

The House of Nassau, while not as grand as the ruling dynasties of Bavaria or Saxony, had roots that went just as deep into the medieval history of the Holy Roman Empire. They emerged as lords of one of the strategic corridors along the Rhine valley, where the river Lahn enters the Rhine from the east, just a bit upriver from Koblenz. In about 1125 one of the local lords built a castle overlooking the river at a town called Nassau—later family legends said this was named for a Swabian chieftain, Nasua, who had fought against Caesar’s legions in about 56 BC. I’ve also seen the name taken apart as ‘Nasse Auen’ or ‘vast wet fields’, which perhaps related to the low-lying terrain in this particular bend of the Lahn. Whatever the case, an interesting fact about the castle at Nassau was that it always belonged to the entire dynasty collectively, no matter how many branches and sub-branches it divided into, across nearly six centuries. Each branch developed their own castle-seat, and Nassau ceased to serve as a residence by the 16th century, mostly falling to ruins in the 17th. Its five-sided bergfried, or central fighting tower, dates from the early 1300s, and was reconstructed, along with some other buildings, in the 1960s by the state of Rheinland-Pfalz, its modern owner.

The lords of Nassau at first struggled to demonstrate their independence, finally shaking off the bishops of Worms as overlords by the middle of the 12th century, and taking the title ‘count’. They administered their own lands, collected taxes and tolls on the Rhine, and so forth. So eventually they were known as ‘princely counts’, to distinguish them from mere counts who were subject to greater lords. As with most German noble dynasties, the Nassauers divided almost immediately into several branches. The most significant split occurred in 1255 with the major division between the Walramians and the Ottonians. The elder branch, based primarily at Wiesbaden on the river Main across from Mainz, and at Weilburg, much further up the Lahn, eventually became dukes of a consolidated Duchy of Nassau in the early 19th century, and then grand dukes of a newly independent Luxembourg from 1890. Today’s grand ducal family in Luxembourg are still called the House of Nassau-Weilburg.

The younger line were based much further in from the Rhine, at the north-eastern extremities of the lands held by the House of Nassau, first at Siegen, and then at Dillenburg. The line of Nassau-Dillenburg was separate from about 1300; they constructed a new castle over the river Dill (replacing one made from wood with one made from stone). Its defences were greatly expanded in the 17th century, but were dismantled in the 18th. A new structure was built in the 1870s by a Dutch princess and named the Wilhelmsturm—today it is a museum of Orange-Nassau history, particularly devoted to William the Silent, who was born here in 1533.

In 1405, Count Engelbert, third son of Count Johann I of Nassau-Dillenburg, married a significant heiress from a very different part of the Holy Roman Empire, Joanna van Polanen, from one of the leading families in the province of South Holland. Her inheritance included the lordship of Lek, named for the river Lek and estates east of Rotterdam in the Rhine delta, and the barony of Breda a few miles to the south in the province of Brabant. Breda is strategically located in the high ground between the estuaries of the Maas (Meuse) to the north and the Scheldt to the south. Its 12th-century fortress had been sold by the Duke of Brabant to the lords of Polanen in the 1350s, and it became the seat of the senior branch of the line of Nassau-Dillenburg in the first decades of the 15th century. They rebuilt the fortress as a renaissance palace in the 1530s, later expanded by William III in the later 17th century. It was given to the army by the Dutch royal family to serve as a military hospital in 1826.

Engelbert of Nassau also inherited an even more impressive castle on the other side of the Low Countries, Castile Vianden, deep in the Ardennes, in the Duchy of Luxembourg. It is a very ancient castle, built by a dynasty of counts in about 1090, then rebuilt in Gothic style in the mid-1200s. The last heiress of the original line of counts of Vianden willed it to her cousin Engelbert in 1417 and it became an alternative seat for his family. A later member of the House of Orange-Nassau, Moritz, remodelled it again in the 1620s, now in a renaissance style. In 1820 it was sold by King William I of the Netherlands to a local merchant, who dismantled much of it for parts, until the near-ruin was repurchased and restored by the Dutch royal family as the fashion for Gothic castles came once more into vogue. In 1890, Vianden passed to the House of Nassau-Weilburg with the rest of Luxembourg, and it remained one of the grand ducal residences until ceded to the state in 1977.

Engelbert’s son, Count Johann IV, became firmly embroiled in Burgundian politics and society in the Low Countries. He occupied a prominent townhouse in Brussels, later known as Nassau Palace, on the hilltop near the Duke of Burgundy’s residence, the Coudenberg. He also had a residence in Mechelen, and in his various lordships spread all over the Low Countries. He expanded his control over the Barony of Breda by removing it from vassalage to Antwerp, making it instead a direct fief of the duke of Burgundy (in his capacity as duke of Brabant). In 1440 he married yet another heiress, Mary van Looz, whose inheritance included lands in the prince-bishopric of Liège as well as claims to the important duchy of Jülich in the Rhineland (though these were later denied by Imperial decision of 1499).

Engelbert II, Count of Nassau-Breda and Count of Vianden, entered into service of the Duke of Burgundy and became a commander of his troops in the 1470s, leader of his Privy Council, and a knight of the exclusive Order of the Golden Fleece. Moving smoothly into the service of the Duke of Burgundy’s successor, Maximilian of Austria, Engelbert was at first appointed Stadtholder (or governor) of Flanders in 1490, then rose to the position of President of the Grand Council in 1498 and Lieutenant-General of the Low Countries—effectively the chief Habsburg representative in the Netherlands—from 1501 until his death in 1504. He acquired several more lordships, notably Roosendaal and Wouw, near Breda, and Diest also in Brabant, but today across the border in Belgium.

Engelbert II had no children, so his Netherlandish inheritance passed entirely to his nephew, Heinrich III of Nassau-Dillenburg. Heinrich (or Hendrik) was appointed a chamberlain in the household of young Archduke Charles, soon to become both Carlos I of Spain and the emperor as Charles V. They became quite close, and Hendrik was named a member of his Privy Council, Stadtholder of Holland and Zealand in 1515, and the new emperor’s Grand Chamberlain in 1521, as well as his Master of the Hunt for the Duchy of Brabant. Nassau-Breda represented Charles formally in Germany at the time of his election as emperor in 1519, and accompanied him to Bologna for his imperial coronation in 1530. As a sign of his loyalty, he remained a firm Catholic in the 1530s, when other leading nobles, including his own brother, William ‘the Rich’, were joining the new Lutheran confession. He also accompanied Charles V to Spain several times, and married a Spaniard as his third wife in 1524. As seen above, his previous wife was Claude de Chalon, sister of Philibert, Prince of Orange.

Hendrik of Nassau-Breda had one legitimate son, René who took the surname Chalon, and an illegitimate son with the daughter of the governor of the castle of Vianden, Alexis, who was given the lordship of Corroy in Namur and founded a dynasty (Nassau-Corroy) that became counts in 1693, and lasted until the early 19th century. This medieval fortress, now property of the noble Trazegnies family, is one of the most impressive castles in Belgium.

René de Chalon thus had this great quadruple inheritance: he was count of Nassau in Germany, lord of Breda in the Low Countries, lord of Chalon-Arlay in Burgundy, and prince of Orange in Provence. In his relatively short life he was invested as Stadtholder of Holland and Zealand, 1540, then of Guelders in 1543 after it was conquered by Charles V.

He died just a year later, wounded during the siege of Saint-Dizier, on the frontiers between France and the Duchy of Bar. His wife, Princess Anne of Lorraine took his body initially to her father’s co-capital city, Bar-le-Duc, and here she commissioned one of my favourite tomb sculptures, by Ligier Richier. While René’s body was later transported to Breda for burial, his heart, and the sculpture, remained in Bar.

The massive succession of René de Chalon in 1544, estimated at about 800 towns and castles, was all willed to his cousin, William of Nassau-Dillenburg, with the stipulation that he must have a Catholic education. This donation obtained the Emperor’s approval in 1545, and that of the King of France in 1552, crucial since William was not the direct heir to the lands of the Houses of Orange, Baux and Chalon. This William became the famous William the Silent, leader of the Dutch Revolt against Spanish rule, or William I, Prince of Orange. His father, younger brother of Count Hendrik III, had been known as Wilhelm ‘the Rich’ because his share of the Nassau inheritance had included the rich iron ore in the hills around Siegen and Dillenburg. He was known as a good ruler of his territories, loved by his peasants even in the turbulent years of the 1520s, and formally introduced the Reformation into his territories. Nevertheless, he had a Catholic marriage in 1530, to Juliana of Stolberg, and their son was baptised as a Catholic in 1533.

William the Silent thus had a multi-confessional upbringing, but in either case, very loyal to the Habsburg monarchy. He inherited the Chalon and Breda properties in 1544, then succeeded his father in Dillenburg in 1559, but gave most of these German lands to his younger brothers, of which there were many. Johann VI became lord of Dillenburg, and would ultimately become the ancestor of the later princes of Orange and the Dutch royal family, so we will return to him below. Another brother, Louis (or Lodewijk), was initially the most politically active and devoted to the new faith of the Low Countries, Calvinism. He led a confederation of Dutch nobles to protest the harshness of Spanish rule in 1565, and helped start the Dutch Revolt in 1568. While his older brother was attempting to maintain peace between Spanish and Dutch, Catholic and Protestant factions, Louis was sent to the far south of France to serve as governor of the Principality of Orange. From here he raised troops which he led in support of the French Huguenots at the battles of Jarnac and Moncontour, then across the border into the Low Countries where he was killed in battle against the Spanish at Mookerheyde near Nijmegen in 1574. Younger brothers Adolf and Heinrich were also soldiers in this conflict, the former being one of the first casualties of the war in 1568, and the latter killed at Mookerheyde alongside his brother Louis.

William I, Prince of Orange, as we’ve seen, was compelled by terms of the will of René de Chalon to be educated as a Catholic, and so he was, at the court of Mary of Hungary, Governess of the Low Countries. Mary’s brother Charles V continued to take an interest, and arranged a marriage to yet another heiress, Anna van Egmond, heiress of the county of Buren, an autonomous fief of the Empire enclaved within the Dutch provinces, as well as various lordships in Holland and Zealand. William was named to the Emperor’s Council and supported Charles physically when he was ill and formally abdicated from his royal duties in 1555. At first the Prince of Orange continued in the good graces of the new ruler of the Low Countries, Philip II, and was appointed Stadtholder of Holland and Zealand in 1559, then of the Franche-Comté in 1561. But he soon emerged as a leader of the opposition on the Council, disliking the heavy-handed treatment of Protestants by Spanish troops. In 1561, he married as his second wife Anna of Saxony, daughter of the Elector of Saxony—this was significant in that she was of a far higher rank than his first wife, but also daughter of one of the primary leaders of the Protestant movement in Germany. It was a Lutheran ceremony, but William remained a Catholic. Only later (in 1573) did he become a Calvinist—but by this point he had fully broken with the Spanish king, and had been declared an outlaw and a rebel. In 1581, the Dutch estates began to press for full independence from Spanish rule and declared Philip II formally deposed.

At first the Prince of Orange tried to lure a French royal prince (the Duke of Anjou) to the Low Countries to act as Sovereign Prince, but this prince was not up to the task, and by 1583, William was himself the virtual sovereign of a new nation. Since the 1570s, he had established his court at a recently secularised convent, the Saint Agatha Cloister next to the Old Church in Delft, which became known as the Prinsenhof. He was assassinated only a year later, and buried in Delft’s New Church, which became the sepulchre of the House of Orange-Nassau, which it still is today. The Prinsenhof was later used as a cloth hall, a Latin school, and since the early 20th century, a municipal museum.

William the Silent also increased even further the landholdings of the House of Orange-Nassau in the Low Countries, in particular through the purchase in 1582 of the Marquisate of Veere and Vlissingen. Both of these towns were major shipping centres since in the Middle Ages, both in Zealand, and both with strong connections to seaports in England and Scotland across the North Sea—they were historically known in English as Camphire (the ferry or veere at Campu) and Flushing. By the 16th century, much of the Dutch navy was based at Veere and the Dutch East India Company at Vlissingen. The lordships held by the Van Borssele family since the middle ages passed to the Van Bourgondië family (an illegitimate branch of the Valois dukes of Burgundy), and were erected together into a marquisate by Charles V in 1555. But the family sold the marquisate to Philip of Spain in 1567, whose debts were paid in part by selling it to the States of Holland and Zealand, who then sold it to William of Orange. The Prince intended it to be the main domain of his second son, Maurice, and a political benefit too, as it came with two votes in the estates of Zealand. There had been an old castle at Veere, the Zandenburg (or Sandenburgh), but it soon fell into disrepair and its ruins were dismantled in the early 19th century.

The next Prince of Orange is a bit of an anomaly in the story of Dutch independence. Philip William, the only son from William I’s first marriage, was born and raised as a Catholic, and sent as a hostage to Spain when the revolt broke out in 1568. Unlike his uncles and half-brothers, he remained a devoted Catholic and loyal to the Spanish Habsburgs. He eventually returned to the Netherlands, in 1596, and was allowed to rule the Barony of Breda, though this was contested by his younger brother until 1606. In that year, he married a daughter of the Prince of Condé, cousin to the King of France, so it is clear he had dynastic ambitions. But no children came from the marriage, and he died in 1618.

It would be interesting to know more about the relationship between Philip William and the Principality of Orange itself, especially given his renewed relationships with the French royal family. Certainly under the later ‘reigns’ of his half-brothers and then nephew, it remained a haven for Protestants in a sea of Catholics. There were Protestant schools there, and a Protestant university and seminary. A great new fortress was constructed in 1620 by Prince Maurice, on top of the hill that dominates the centre of the city, the site of the ancient Celtic then Roman fortifications. This was dismantled by French forces when they took over the principality in 1672. More on that below.

The Principality did not consist just of Orange, but of several smaller enclaves across the region, like the Barony of Orpierre, high up in the pre-Alps east of Orange, whose town walls kept its Protestants safe in the 17th century. Or the castle of Suze-la-Rousse, north of Orange, which had served as the summer residence of the medieval princes, but since the 15th century belonged to an allied family, La Baume de Suze.

Maurice of Nassau, only son of William the Silent’s second marriage (to Anna of Saxony), took up his father’s role as leader of the Dutch Revolt. He was almost immediately appointed statdtholder of all the Dutch provinces (except Friesland), and Captain-General of the United Provinces in 1587. He made a name for himself in history as a successful military commander and reformer—a key exemplar of the so-called ‘military revolution’ that stressed tactics and professionalism in creating the modern army. He was Prince of Orange for only a few years, from 1618 to 1625, then was succeeded by another half-brother, Frederick Henry.

Like his father, Maurice (or Moritz in Dutch) also expanded the family landholdings. In 1594, he was named heir to the Imperial County of Moers (sometimes spelled Meurs or Mörs), on the Rhine between the Duchy of Cleves, the lands of the Archbishop of Cologne and the Duchy of Guelders (still contested between Dutch and Spanish forces). The last sovereign countess had been run out by the Spanish, so she willed the County and its castle (the Moersschloss) to Maurice, who retook it by force in 1597. Possession was contested by the Duke of Cleves-Jülich, and although he agreed to its possession by the House of Orange-Nassau, his family continued to use the title Count of Moers well into the 18th century. Moritz also conquered in 1597 the Imperial County of Lingen, further to the east in Westphalia, a property that his father had been forced to sell to the Habsburgs in 1550. Neither Moers nor Lingen were ever incorporated into the Dutch lands, but remained separate possessions of the dynasty. Their coat of arms now (in some versions) sported not just the various quarters of the House of Nassau, but also the escutcheons of Orange, Chalon-Arlay and Geneva, and now new shields (above and below the centre escutcheon) for Veere & Vlissingen (black and silver) and for Moers (gold and black).

Frederick Henry of Orange-Nassau, youngest son of William I and his fourth wife Louise de Coligny, also took over from his brother as statdtholder of all Dutch provinces except Friesland (which had its own line of Nassau statdtholders, who we will encounter below), and was also appointed Captain-General of the Union. He’s remembered as an equally capable general, but a better politician than his brother Maurice, and is known in particular for the capture of the main Spanish military base, ’s-Hertogenbosch, in 1629.

This was the Golden Age for the Dutch Republic, and a high point for the stadtholderate. New residences were renovated or commissioned to develop a proper princely court at The Hague—Amsterdam remained a mercantile city, and what is now the Royal Palace was built in this period as the City Hall. The Hague, formally ’s-Gravenhage (‘the count’s wood’) had been the seat of the medieval counts of Holland, then the meeting place of the States of Holland (and thus the residence of the stadtholders, representatives of now absentee counts), and of the States General of the United Dutch Provinces since the 1580s, so it made sense to establish the court of the Prince of Orange here. Prince Frederick Henry enlarged a palace he had inherited from his mother, Louise de Coligny, Noordeinde. It had been built in the 1530s as a residence of one of the senior officials of the States of Holland in the ‘North End’ of The Hague, and was given to Louise as widow of William the Silent by the States of Holland in 1595. In the 1640s, Frederick Henry added two wings, to give it an H shape (it was called the Oude Hof in this period). Nationalised during the period of the Batavian Republic (1790s), it was named as one of the three official royal palaces once the Netherlands became a Kingdom in 1815, and was used as the main winter residence in the 19th century. Noordeinde Palace was badly burned in 1948, so the monarch resided elsewhere. In 1984 it became formally the ‘office’ or chief working space of the monarch.

On the other side of The Hague, deep in a wood, Frederick Henry’s wife, Amalia von Solms, commissioned a new residence, Huis ten Bosch (‘the house in the wood’), on lands given to her by the States General in 1645. After her husband’s death in 1647, the Dowager Princess filled the central hall, the Oranjezaal, with paintings by the finest Dutch artists, commemorating her husband’s life and the history of the House of Orange. Two large wings were added in the 1730s. Like Noordeinde Palace, the Huis ten Bosch was confiscated by the Batavian Republic, then given for use to the royal family in 1815, again, as one of the three official residences (the other was the Royal Palace in Amsterdam). Extensively renovated in the 1950s, it became the principal residence of Queen Beatrix in 1981, and since 2019 of the current royal family.

Prince Frederick Henry was also the head of an expanding princely dynasty: he had many half-sisters whose unusual second names reveal the growing association of the House of Orange-Nassau with the Dutch Republic: Catharina Belgica, Charlotte Flandrina, Charlotte Brabantina, and Emilia Antwerpiana. These were not just symbolic names, but in fact were given to demonstrate that the estates of these provinces were acting as formal godparents to these girls, and would thus look after them, spiritually and financially if needed. Several of these secured dynastic ties through marriage to other leading Protestant families in Northern Europe, as did, most importantly, the oldest sister, Louise Juliana, who married Frederick IV, the Elector Palatine: their son would unite Protestant Europe in marrying the daughter of King James of England, and this couple would ignite the Thirty Years War in 1618 by accepting the throne of the Kingdom of Bohemia.

Frederick Henry also had lots of daughters, but only one son, William II, to whom we will return to below. But there were also ‘unofficial’ members of the House of Orange-Nassau: both Prince Maurice and Prince Frederick Henry had illegitimate sons: Maurice’s son, Louis (Lodewijk) founded a new line, the lords of Ouwerkerk (in South Holland), who became better known as the family Nassau-Auverquerque in French, or ‘Overkirk’ when they moved into English society in the 1660s. The last of these was Earl of Grantham from 1698 to 1754. Frederick Henry’s son, Frederik, also founded a line, based in the lordship of Zuylestein (in the Province of Utrecht), who were eventually given an English earldom, Rochford (created in 1685; extinct in 1830).

More relevant to our story, the first Lord of Zuylestein was appointed as governor of the household of his younger half-brother, William II, who became Prince of Orange in 1647, and then of William’s young son, William III, who became Prince of Orange only three years later in 1650. Frederik of Nassau-Zuylestein was also a captain of the Dutch infantry, and helped forge closer ties between the Houses of Orange and Stuart when in 1648 he married Mary Killigrew, a maid-of-honour of the Princess of Orange, Mary Stuart, daughter of Charles I. Princess Mary was named Regent of her young son, and together she and Zuylestein tried to preserve some of the status and authority of the role of stadtholder—much of which had been lost in the brief reign of William II, who had opposed the peace offered to the Dutch in the Treaty of Westphalia of 1648, and quarrelled with the Estates of Holland who wanted to reduce the size of the army following the peace. William II was only 24 when he died of smallpox.

William III was born a week later. In addition to his mother and Zuylestein, the Prince was formally looked after by his grandmother, Amalia van Solms (a source of tension for the British princess, who thought her mother-in-law, born a German countess, was beneath her), and his uncle, Frederick William, the Elector of Brandenburg. The fact that a Hohenzollern was his uncle will be important later when we come to the next stage in the succession of the principality of Orange, so keep that in mind. William’s mother died in 1660, so his other uncle, King Charles II of England got involved and convinced the Dutch Estates to declare the Prince a ‘Child of State’ in 1666. Zuylestein was pushed aside, and the job of stadtholder was nearly abolished (Holland and others did formally abolish it in 1670). What would be the role of the House of Orange-Nassau in the Republic now?

When war broke out with France in 1672, the Prince of Orange was appointed Captain-General, temporarily, but when the actual invasion of the largest army in Europe began, William was swiftly appointed Statdholder of Holland and Zealand. After his first victories on the battlefield, he was appointed hereditary (not just for life) stadtholder in Utrecht (1674) and then Gelderland (1675). From here on, William III’s history is quite well known, as builder of great European coalitions against Louis XIV, preserving Dutch independence in the 1670s, and then leading the Glorious Revolution in England where he was named king (in conjunction with his wife, also named Mary Stuart) in 1689. William and Mary also gave their name to a new college in the colony of Virginia, which I attended exactly three centuries later.

Like his grandfather and great-uncle, William III also expanded his family holdings in the Dutch Republic through the purchase of a house at Soestdijk, and construction of the Palace of Het Loo. Soestdijk was built in the mid-17th century by one of the leaders of the Republic, Cornelis de Graeff, who also took charge of young William’s education in the 1650s, often keeping him at Soestdijk, in the Province of Utrecht, to be raised with his sons. In 1674, one of Cornelis’ sons then sold the house to the Prince, who rebuilt it as a hunting lodge. After the revolutionary period, it was returned to the family as private property, and Queen Juliana used it as her residence (though she gave it to the state in 1971) until her death in 2004. In 2017 it was sold to a private developer and there are plans to renovate the palace as a public venue, but also to add housing, a hotel and other elements to the site.

Further east, in the province of Gelderland, William III built another hunting lodge, called Het Loo (‘the lea’, or forest clearing), near Apeldoorn. This was built swiftly in 1685-86, and he added extensive baroque gardens. It would serve as the chief summer residence for the Dutch kings in the 19th century until 1962; since 1984 it has been a state museum, and the baroque gardens have recently been restored, to great acclaim. Het Loo Palace was one of the first royal buildings I ever visited, on a trip by the Choir of the College of William and Mary to Europe in 1993, and it made a deep impression on me as the legacy of King William III.

William himself did not long enjoy his new palaces, however. On the eve of building one final huge European coalition to contain the ambitions of Louis XIV and the House of Bourbon, William III suddenly died, March 1702. He and Mary had no children, and the succession to the Principality of Orange became a heated international diplomatic issue.

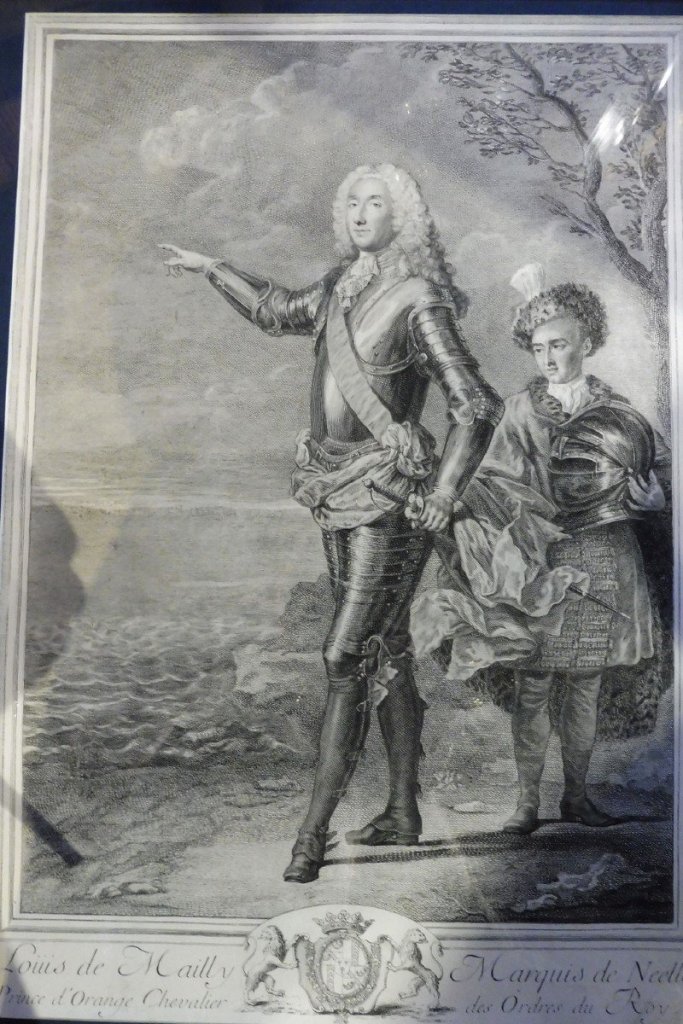

The Principality of Orange had been occupied by France at the start of the Dutch War, 1672, and its fortifications dismantled. In accordance with the Treaty of Utrecht, 1713, Louis XIV formally acquired the principality (and all its smaller enclaved lordships in Provence and Dauphiné), and finally ended its ancient status as a sovereign principality. At least two (possibly three) French claimants emerge to the titles and lands of the princes of Orange. The confused testament of Louis de Chalon, Prince of Orange, back in 1463, had put forward heirs in the House of Seyssel (a frontier family between Burgundy and Savoy), but they had died out and claims made by cousins were thrown out. A younger brother of Louis, Jean, Seigneur de Vitteaux, inherited some Chalon lands in Burgundy, notably L’Isle-sous-Montréal, which passed through several female successions eventually into the House of Mailly by the late 17th century. Louis-Charles de Mailly-Nesle accompanied Louis XIV on his conquest of Franche-Comté in 1674, and was recognised (some said) by the King as the heir to the House of Orange-Chalon (recall that the transfer of titles and properties from René de Chalon to William the Silent in 1544, seen above, was considered legally dubious by several jurists, notably French ones…). Mailly took the title ‘Prince of Orange and L’Isle-sous-Montréal’, and in 1706 was authorised to use it by the French king. When he died in 1708, his grandson, Louis III de Mailly, Marquis de Nesle, took up the princely title and even moved in to take possession of the Orange estates in 1710 (and one of his sisters married a Prince of Nassau-Siegen, meaning some later members of that family also later claimed the title). But when the actual settlement with the House of Orange-Nassau was made in the Treaty of Utrecht of 1713, Louis XIV changed his mind, and bestowed the lands (and the title Prince of Orange) formally on his cousin, the Prince of Conti (Louis-Armand de Bourbon), as heir to yet another Chalon heiress: Alix, the sister of Prince Louis and Jean de Vitteaux, who was named as heiress presumptive by their mother, Marie des Baux. Alix’s claims passed through various families before it ended up in the House of Orléans-Longueville (an illegitimate branch of the House of Valois). François, Duke of Longueville, had attempted to claim the succession in 1544, and he and his nephew and heir obtained some legal wins in French law courts, but were unable to make good of them due to the prominence of William the Silent. The last Duke of Longueville died in 1694, leaving Conti as his heir. Conti was to hold the principality in usufruct until he died; which he did in 1727, and shortly thereafter, the Principality formally merged with the Crown in 1731. The Mailly claimants continued to use the title well into the 19th century.

But there were other claimants, not just to the Principality of Orange, but to the vast Orange-Nassau family properties in the Low Countries, including Breda, Veere & Vlissingen, and the various residences in The Hague, Soestdijk and Het Loo. There were also the Chalon lands in Burgundy, the County of Vianden in Luxembourg, and the Imperial County of Moers. The closest kin to William III when he died in 1702 was actually his cousin, Frederick William I, King of Prussia, who claimed the Principality and the other Nassau titles and estates. He ceded his rights to Orange itself to the King of France by the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713, though retaining use of the title for himself and his descendants. The specific terms of the Treaty specified the King of Prussia could create a new principality of Orange in the Prussian portion of the province of Gelderland (to be based on the town of Geldern, the land of Kessel and other towns and lordships, now in Germany), but I’m not sure if this was ever done, even on paper. The Hohenzollerns continued to use the title ‘Prince of Orange’ as late as 1918.

But Orange was also claimed in 1702 by Johan Willem Friso of Nassau-Dietz. Jumping back to the mid-16th century, one of the younger brothers of William the Silent was Johann VI, Count of Nassau-Dillenburg. Like so many members of this family, he too was involved in the Dutch Revolt, was named Stadtholder of Gelderland, and was one of the principal leaders responsible for the forging of the Union of Utrecht, 1579, the declaration that bound together the northern Dutch provinces in their rebellion against Spanish rule. In 1606, his estates were divided between his five living sons. The eldest, Wilhelm, received Dillenburg, but stayed in the Netherlands where he was appointed stadtholder of Friesland, the northernmost of the Dutch provinces, in 1584. Like his cousins, he was one of the leading commanders of the Dutch army and a military reformer. He solidified links between the branches by marrying his cousin, Anna of Orange-Nassau, but they had no children. The second son, Johann VII received Siegen as his portion of the county of Nassau. He was also known as a military reformer, but he served in a different theatre, with the armies of Sweden in its wars in the Baltic. The fourth son, Ernst Casimir, was given Dietz as his portion of Nassau in 1606 then succeeded his eldest brother as stadtholder of Friesland in 1620. He starts therefore a secondary Dutch line, Nassau-Dietz, also known as the Frisian Branch. We’ll return to them in a moment, but first we need to look at what happens to the Imperial branches of the House of Nassau in the 17th century.

Johann VII, Count of Nassau-Siegen had, with two wives, 21 children. Two of the sons, Johann VIII and Johann Moritz, formed new sub-branches, both called Nassau-Siegen, one Catholic and one Protestant. Johann VIII shocked his family by converting to Catholicism in 1613, and joining the Imperial armies. Johann Moritz retook Siegen from his brother and reversed his efforts at recatholicization, then led a long and interesting career in service of the Dutch Republic, notably as Governor of Dutch Brazil, 1636 to 1643, then Governor of the Duchy of Cleves for the Elector of Brandenburg, from 1648, and finally Commander-in-Chief of Dutch land forces, 1664, for the Republic’s war against England. He gave his second name to the house he built in The Hague, the Mauritshuis, today a fantastic museum.

In 1650, the two Siegen counts’ uncle, Johann Ludwig of Nassau-Hadamar, an Imperial diplomat (and another convert back to Catholicism), was raised by the Emperor from the rank of count to fürst, ie, ruling prince. This started a trend within the family to press for a similar rank for all its members, and two years later, both branches of Nassau-Siegen were made princes of the Empire, as were the counts of Nassau-Dillenburg and Nassau-Dietz in 1654. Several lines of the other major branch of the dynasty (the Walramians) were later also raised to princely rank, in 1688 (Weilburg, Idstein, Usingen).

So from 1654, Nassau-Dietz was a principality. The Castle of Dietz (today Diez), on the river Lahn, was built in the 11th century and acquired by the Nassau family through marriage in 1384. South of Dillenburg and Siegen, it was much closer to the old core of the County of Nassau. From the 1680s, the family, when in residence in Germany, moved out of the old castle and into a new palace, Oranienstein, on the edge of town (built on the ruins of a former abbey), and the old castle of Dietz was used as estate and government offices. The Dutch royal family lived in exile at Oranienstein during the period of the Batavian Republic. After 1866 it was given to the Prussian Army who developed it for military use (a cadet school, barracks, medical facilities, and it is still operated by the German military today. Diez Castle now houses a youth hostel and a local history museum.

But in the 17th century the family of Nassau-Dietz spent most its time in Friesland. They had acquired a large house in the provincial capital, Leeuwarden, in 1587, which has since been known as the Stadhouderlijk Hof, or Stadtholder’s Court. In the later 17th century, one of the Frisian line of stadtholders, Willem Frederik, added a lavish garden, the Prinsentuin Garden, which survives today. The Hof itself is, since 1996, a hotel.

This Willem Frederik was stadtholder of Friesland from 1640. Like several members of his family, he re-joined his Nassau bloodline by marrying the daughter of Frederick Henry, Prince of Orange, in 1652. After the death of Prince William II in 1650, Willem Frederik tried to act as guardian for the infant William III and leader of the Orangist Party in the Republic, without much success. He died in 1664, arranging for his seven-year-old son to be named stadtholder of Friesland under the regency of his mother. Albertine Agnes of Orange-Nassau.

Henry Casimir II, Prince of Nassau-Dietz, was stadtholder of Friesland and Groningen from 1664 to 1696. He seems to have led a fairly uninfluential life, frustrated as a military commander to such an extent that he defected for a time into French service (and thus into opposition of his nephew William III), then resigning when passed over for top command once again in 1693. But he did leave the stadtholderate of Frisia intact for his son, Johan Willem Friso—indeed it was confirmed as hereditary in his family in 1675. When William III died in 1702, the succession to the main line had a problem. William’s will had named the descendants of his aunt, Albertine Agnes of Orange-Nassau, as his heirs: that is, Johan Willem Friso of Nassau-Dietz. But an older will, of Prince Frederick Henry, named the descendants of his elder daughter Luise Henriette, wife of the Elector of Brandenburg. In 1702 therefore, the Elector of Brandenburg, recently promoted to King in Prussia as Frederick I, claimed the Orange succession, as we’ve seen above.

Meanwhile, Johan Willem Friso continued to press for his own claims to the Orange-Nassau succession. Finally in 1732, his son William IV made a treaty of partition with the Hohenzollerns of Prussia and they agreed to share the revenues and the title. By this point of course, no one was actually prince of Orange. The agreement pertained more to returning estates and residences in the Netherlands to the new House of Orange-Nassau, notably Noordeinde Palace and Het Loo (financial haggling continued into the 1750s).

Johan Willem Friso had been stadtholder of Friesland and Groningen from 1702, but the other five provinces suspended the office rather than elect him. In 1707 he served as a general in the War of Spanish Succession under the Duke of Marlborough, but he died fairly young in 1711. His son William IV was elected stadtholder of Friesland and Groningen in 1711, with his mother as regent, and later in Gelderland, 1722. In 1739, he inherited the lands of Nassau-Dillenburg, and in 1743, those of Siegen and Hadamar, unifying the northern half of the old imperial county once again. As Prince of Nassau-Dietz he had to balance his interests between the Netherlands and the Holy Roman Empire, and in 1747 he supported the Habsburgs in their war against Prussia and France. The Dutch Republic did too, and when France invaded, he was named stadtholder of the other three main provinces (Holland, Zealand and Utrecht) and then the first Hereditary Stadtholder of the United Provinces, ending the Second Stadtholderless period—this is known as the ‘Orangist Revolution’. He and his family moved their court from Leeuwarden to the princely court at The Hague.

Prince William IV’s ‘royal’ status had been enhanced a few years earlier when he married his cousin, Anne, Princess Royal of Great Britain—and several places were named in his honour in the British colonies, like the County of Orange in Virginia, and Orangeburg, South Carolina. Of course there were also Dutch possessions given the Orange name in the 18th century: the capitals of both Aruba and Sint Eustatius in the Caribbean (Oranjestad); the longest river in South Africa, the Orange (which gave its name to the Orange Free State); even Cape Orange on the borders between Brazil and the Guianas. As a ruler, the Prince of Orange tried to reform the tax burdens on ordinary folk of the countryside, but he was definitely allied with the urban merchant elites as well, and was appointed one of the directors-general of the Dutch East India Company. The Prince of Orange was keen to build this collection of provinces into a unified state—he demonstrated his devotion to this ‘national’ idea even by naming his son, born just one year later, William Batavus. But he died rather suddenly in 1751.

Since the role of stadtholder of all the provinces was now hereditary, his son William V succeeded to this role. But he was only three, so was governed by a string off regents: his mother, Anne of Hanover, his grandmother, Marie Louise of Hesse-Kassel, then his cousin and one of his father’s trusted generals, Duke Ludwig Ernst of Brunswick-Bevern, and finally briefly, his older sister Caroline for one more year until he reached his majority in 1766. A year later he married another cousin, Wilhelmina of Prussia, niece of Frederick the Great, thus fully reconciling the families who had been rivals over the Principality of Orange.

The former regent Brunswick-Bevern stayed on in the Netherlands as Prime Minister until his overtly pro-British policies and close links to Emperor Joseph II clashed with Dutch interests, and, the Dutch faring badly in its war with Great Britain in the early 1780s, he was forced from power in 1784. By association, William V and the idea of a hereditary stadtholder were now increasingly unpopular, and he faced armed uprisings in 1786 and ’87 (and the States of Holland took away his title Lieutenant-General of the Army). His wife was attacked, leading her Prussian relatives to see this as an affront too far so they invaded in September 1787 to suppress the Patriots Party. It was too late to put the lid back on the bubbling revolution about to erupt and it joined up with revolts in France and the Austrian Netherlands just across the southern borders. In January 1795, exiled Patriots returned to the Netherlands and forced the Prince of Orange into exile. The Batavian Republic was proclaimed and the properties of the House of Orange-Nassau were confiscated. William went to Britain to try to obtain assistance, but in 1802, Britain recognised the Batavian Republic (an ally of Republican France), and a Franco-Prussian convention later that year decided that the House of Orange could be compensated for its losses of estates in the Netherlands through the creation of a new Principality of Orange-Nassau-Fulda, with various secularised church lands in Holy Roman Empire, notably the former abbeys of Fulda and Corvey. William V ceded this immediately to his son, in 1803, and died in exile in Brunswick in April 1806.

The reign of William Frederick, Prince of Orange-Nassau-Fulda, lasted only a few more months. He had refused to join Napoleon’s Confederation of the Rhine, so the new Emperor of the French dissolved the principality in July 1806, and incorporated these territories, as well as the older Nassau lands, into new states he was creating: the Grand Duchy of Berg for his brother-in-law Joachim Murat, and an expanded Duchy of Nassau for the rival line of Nassau-Weilburg. Succeeding his father—at least in Orangist eyes—as William VI, Prince of Orange—he fought against Napoleon in the armies first of Prussia, then Austria. As the tide began to turn the Batavian Republic crumbled and in November 1813, he was asked to return to the Netherlands as ‘Sovereign Prince of the United Netherlands’—with strong support from the Russian Tsar, Alexander I (this alliance would soon be sealed by a marriage between his son and the Tsar’s sister, Anna Pavlovna). He was also given back his lands in the county of Nassau itself. The treaties following Napoleon’s surrender in June 1814 gave him rule over the former Austrian Netherlands as well (as governor-general), but by March of 1815, he proclaimed that he was to be king of a United Netherlands (north and south), later approved by the Congress of Vienna. The new King William I promised to rule with a constitution for the new kingdom, and ceded his dynastic lands in Nassau to Prussia in exchange for the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg.

There was discontent with the rule of King William I in the south almost from the start, and the last years of his reign were consumed by the Belgian Revolution of 1830-39. He was also increasingly alienated from the liberal leanings of his Dutch political leaders, and in 1840 abdicated in order to marry a non-royal Belgian Catholic, the Comtesse d’Oultremont. He died in 1849 as simple ‘Count of Nassau’.

William I had started the tradition of naming his heir ‘Prince of Orange’. William Frederick George was much more popular than his father, both in the Netherlands and in Great Britain, in whose forces he had served with skill in the Napoleonic wars. He was one of the commanders of the Allied troops under Wellington at Waterloo in 1815, and the many pubs in Britain still known today as the ‘Prince of Orange’ are probably named for him (but I’d need to do some pubcrawl research to be sure): one in east Manchester (appropriately on Wellington Road, in Ashton), one in rural Somerset, one in Gravesend, Kent, and a recently closed one in Rotherhithe, southeast London (there’s also one in Torquay in Devon, but I think we can assume that is named for William III who landed his troops there in 1688). He became King William II in 1840.

William I had a second son, Frederick, who potentially could have started a cadet line, first intended to inherit the German lands, then after 1815 perhaps the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg. But in 1816, he gave up this idea and accepted the title ‘Prince of the Netherlands’ (and a large stipend), and devoted his energies to reorganising and modernising the Dutch army. Another potential for rule came his way in 1829, when he was offered the Greek throne, but he was not interested. After his father’s abdication, Prince Frederick retired from politics, and bought a large private estate in Germany: Muskau, near Görlitz in Saxony, close to the modern border with Poland, where he developed its gardens, reckoned the largest and most famous English-style garden in all of Central Europe.

The nineteenth-century history of the princes of Orange is really therefore the history of the royal family of the Netherlands (so less pertinent for a blogsite about dukes and princes). King William II’s son William was entitled Prince of Orange from 1840-49, then succeeded as William III. His eldest son (named, surprise, William) was Prince of Orange 1849-79, but was one of those mid-19th-century royals who simply could not stomach the idea of a stiff and restrained life as a royal prince, so spent his days in Paris (where he was delightfully known as ‘Prince Lemon’) and drank himself to death before he turned 40.

The last Prince of Orange until recent times was thus William III’s second son, Alexander, from 1879 to 1884. Quite unlike his older brother, he was more of an intellectual and very interested in politics. But he too died before his father, only a few years later of typhus, leaving a four-year-old half-sister, Wilhelmina. Wilhelmina was not called Princess of Orange, as her father the King held out for a few more years for a male heir. But when he died in 1890 she did succeed him as sovereign of the Netherlands, though not of Luxembourg, which insisted on males-only succession. Due to a Nassau family pact from many generations before, the Grand Duchy now passed to the House of Nassau-Weilburg, as we’ve seen above. Neither Wilhelmina’s daughter, Juliana, nor her grand-daughter, Beatrix, was called Princess of Orange—as far as I can tell—when they were heir to the throne. The tradition was revived for Beatrix’s son, Willem Alexander, when she became queen in 1980; he then broke with tradition and named his daughter Catharina-Amalia, Princess of Orange, when he ascended the Dutch throne in 2013.

(images Wikimedia Commons)

hello, my name is last name is Nassau, my father and his father both Nassau’s and Dutch decent too and have said we are “related to queen whilemina” being both reputable and kind of secretive about it, as my grandfather was raised in Australia and his parents died when he was very young I wish to get in contact with someone to do a patriarchal DNA test, I don’t know how “illegitimate children of Nassau get to retain the last name Nassau.

LikeLike

Hello Craig. that’s interesting information! There’s a long history of the illegitimate children of (mostly Germanic) royal families being given the place name as a surname (but usually without the ‘von’ to indicate they were not noble…so Nassau, not von Nassau). Today’s Dutch royal family does this still, but now also for junior members who don’t want to be fully royal and carry out royal duties. I don’t know any specifics about doing DNA testing, but I suspect there would be some official ‘house genealogist’ for the Dutch royal family today who you might contact via their website. https://www.royal-house.nl/

LikeLike